Abstract

Vertically aligned SnO2 nanowire arrays have been in situ fabricated on a silicon substrate via thermal evaporation method in the presence of a Pt catalyst. The field emission properties of the SnO2 nanowire arrays have been investigated. Low turn-on fields of 1.6 to 2.8 V/μm were obtained at anode-cathode separations of 100 to 200 μm. The current density fluctuation was lower than 5% during a 120-min stability test measured at a fixed applied electric field of 5 V/μm. The favorable field-emission performance indicates that the fabricated SnO2 nanowire arrays are promising candidates as field emitters.

Introduction

SnO2 is a wide bandgap semiconductor (Eg = 3.6 eV, 300 K) which has been widely applied in gas sensors, solar cells, lithium-ion batteries, and nanoelectronic devices [1-4] due to its outstanding optical and electrical properties [5]. Nanoscaled SnO2 presenting peculiar properties superior to its bulk counterpart because of the quantum effects has attracted much interest in recent years. Various methods have been developed to fabricate a SnO2 nanostructure, including thermal evaporation of the metal tin (Sn) [6], sonochemical method [7], carbothermal reduction [8], hydrothermal method [9], electrodeposition method [10], and so on. The field-emission [FE] properties of SnO2 nanobelts, nanoflowers, [11] and nanowires [12] were also studied considering the potential applications of FE flat displays, X-ray sources, and microwave devices. It was found that the nanowires and long nanobelts of SnO2 exhibited outstanding FE properties [13-15]. In general, vertically aligned nanowire arrays are the best candidates for FE sources because the efficiency of the field emitters is based on the extremely small radii of the tips, and the diameter of the nanowire, the precise position, and the alignment can be well controlled [16-18]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a method to fabricate well-aligned SnO2 nanowire arrays to further improve the FE performance.

In this work, an in situ catalytic thermal evaporation method was developed to fabricate vertically aligned SnO2 nanowire arrays on a silicon substrate. The FE characteristics of the SnO2 nanowire arrays were studied. The in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays, benefiting from the well-aligned structure and the in situ-grown fabrication method, demonstrated favorable low turn-on electric fields and a relatively stable emission behavior.

Experimental details

For preparing the SnO2 nanowire arrays, 2 g of tin powder (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was put in a ceramic boat. A silicon (100) substrate sputtered with a 5-nm-thick Pt film was placed on the top of the ceramic boat. The distance between the tin powder and the substrate was about 0.5 cm. The ceramic boat was placed in the middle of an electric resistance tube furnace. The electric resistance tube furnace was purged with a continuous 100-sccm high-purity nitrogen gas for 15 min beforehand. Then, it was heated up to 850°C at a rate of approximately 30°C/min and kept at 850°C for 10 min. Lastly, it was cooled down to room temperature naturally, and a white layer of product was found on the silicon substrate.

The surface morphology and crystal structure of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays were investigated by scanning electron microscopy [SEM] (JEOL JEM-6320F, JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy [HRTEM] (JEOL JEM-2100, JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), and X-ray diffraction [XRD] (Bruker-AXS D8, Bruker Optik Gmbh, Ettlingen, Germany). The optical properties of the in situ-grown nanowire arrays were studied by Raman spectroscopy (French Labrum-HR cofocal laser micro-Raman spectrometer (Dilor S.A, Villeneuve d'Ascq, France) using an argon-ion laser at 514.5 nm).

The FE measurements were performed in a vacuum chamber at a pressure of 3 × 10-5 Pa at room temperature. The silicon substrate with the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays served as the cathode, and a fluorine-tin-oxide coated glass served as the anode. The cathode and anode were separated with mica spacers. The applied electric field (E) was determined by dividing the applied voltage (V) by the anode-cathode separation (d). The emission density (J) was evaluated from the quotient of the obtained emission current divided by the cathode surface area (0.25 cm2).

Results and discussion

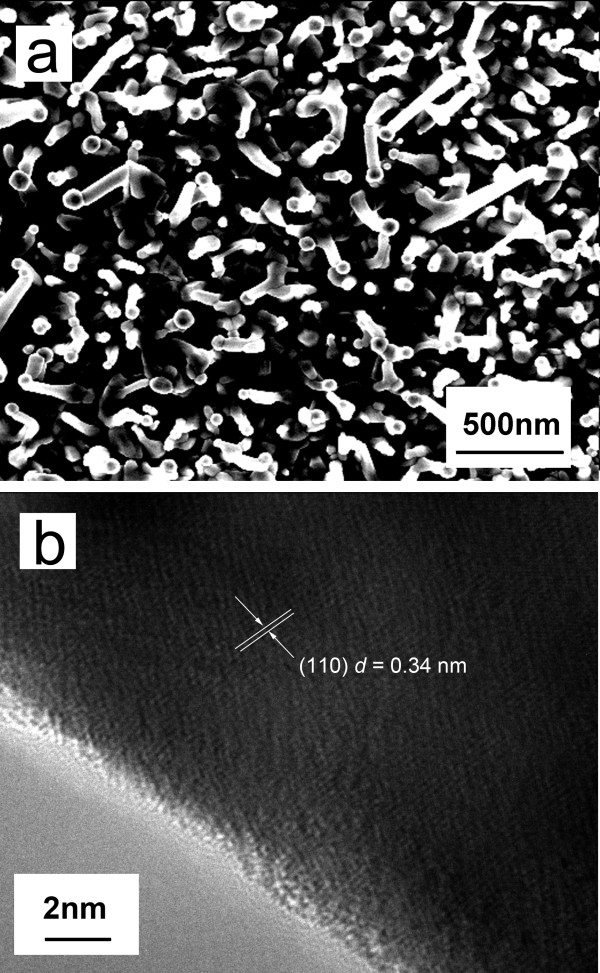

Figure 1a shows a top view SEM image of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays. It can be seen that the nanowire was vertically aligned on the silicon substrate with diameters between 40 to 60 nm. Noticeably, on the top of each nanowire, there was a globule, which strongly indicates that the nanowire grew via a vapor-liquid-solid mechanism [19]. The density of the SnO2 nanowire arrays, determined by counting nanowires in a representative area of a SEM image, was estimated to be 3 × 107/mm2. Figure 1b presents a high-resolution TEM image of a single SnO2 nanowire. It shows that the SnO2 nanowire is a single crystalline nanowire with an interplanar spacing of 0.34 nm corresponding to the (110) plane of a rutile crystalline SnO2.

Figure 1.

Morphology characterization of the prepared SnO2 nanowire arrays. A (a) typical SEM image and (b) HRTEM image.

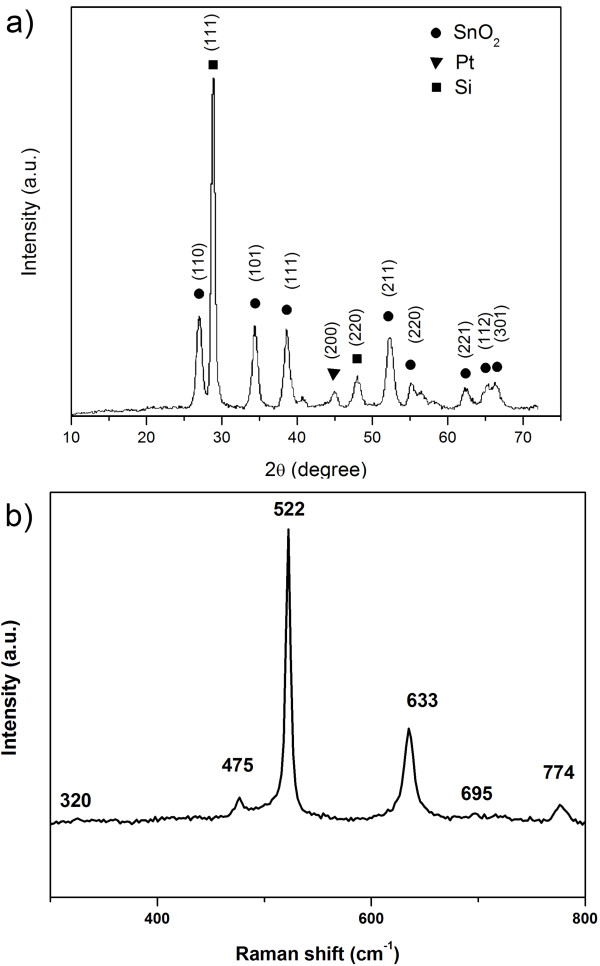

XRD characterization was employed to investigate the crystal structure of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays. Figure 2a shows a typical XRD pattern. The diffraction peaks can be well indexed to the standard values of bulk SnO2 (JCPDS card: 41-1445), Si (JCPDS card: 27-1402), and Pt (JCPDS card: 88-2343). The peaks attributed to SnO2 demonstrate that the in situ-grown sample crystallized with the tetragonal rutile structure with lattice constants of a = 4.738 Å and c = 3.187 Å.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction pattern (a) and Raman spectrum (b) of the prepared SnO2 nanowire arrays.

A typical room temperature Raman spectrum of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays is shown in Figure 2b. It can be seen that there were three fundamental Raman peaks located at 475, 633, and 774 cm-1, which correspond to Eg, A1g, and B2g vibration modes, respectively. The results are in good agreement with those of the rutile single crystal SnO2 nanowire reported previously [20]. Besides the fundamental Raman peaks, the other two Raman peaks located at about 320 and 695 cm-1 were also observed, which correspond to IR-active Eu3TO and A2uLO (TO is the mode of transverse optical phonons; LO is the mode of longitudinal optical phonons) modes, respectively [21]. The strong and sharp peak located at about 522 cm-1 corresponds to the characteristic peak of the silicon substrate [22,23]. It is believed that the broadening of the peaks in the Raman scattering results is attributed to the quantum confinement effect of the sample [24].

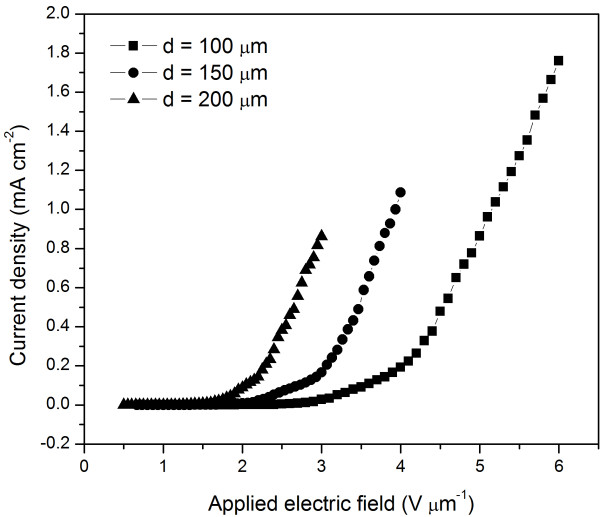

To investigate FE properties of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays, FE measurements were performed at various anode-cathode separations. Figure 3 presents the FE current density (J) of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays as a function of the applied electric field (E) measured at anode-cathode separations of 100, 150, and 200 μm. The turn-on field is defined as the applied electric field which produces a current density distinguished from the background noise (here, defined as 0.01 mA cm-2) [25]. It can be seen from the figure that the turn-on fields were dependent on the anode-cathode distance: their value decreased as the anode-cathode distance increased, and the turn-on fields were measured to be 2.8, 2.0, and 1.6 V μm-1, respectively. These values are lower than those reported by He et al. [26] (5.8 V μm-1) and Wang et al. [27] (3.77 V μm-1) for the SnO2 nanowire. The lower turn-on fields may be attributed to the good alignment of the SnO2 nanowire. Additionally, we believe that the in situ fabrication method, which made good electrical contacts between the SnO2 nanowire and the silicon substrate, contributed greatly to the lower turn-on fields. Moreover, the emitter radius of the SnO2 nanowire among the arrays was approximately 50 nm, which is small enough to make the FE performance excellent [28].

Figure 3.

Field-emission current density as a function of the applied electric field. The measurements were performed at various anode-cathode separations of 100, 150, and 200 μm.

In order to understand the emission characteristics, FE properties were also analyzed by applying the classic Fowler-Nordheim [FN] law using the following equation [29]:

| (1) |

where J is the FE current density, Φ is the barrier height of the emission tip surface, and Eloc is the local microscopic electric field at the emission sites. The a and b in the equation are constants with value of 1.54 × 10-10 (A V-2 eV) and 6.83 × 109 (V eV-3/2 μm-1), respectively. Eloc, which could be up to a hundred or thousand times of the macroscopic electric field between the cathode and anode, can be calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

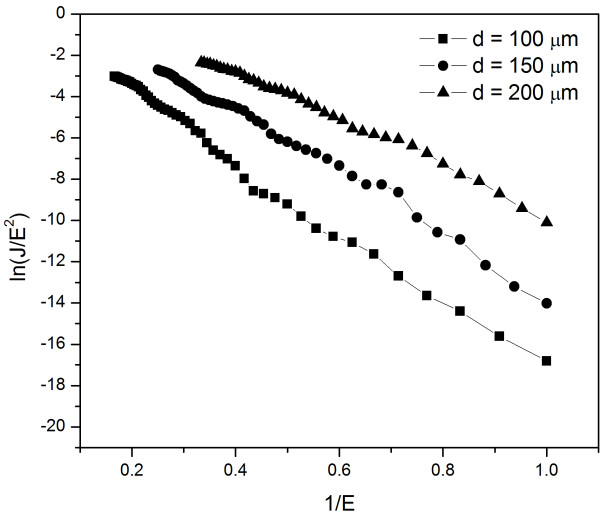

where β is the field enhancement factor, V is the applied voltage, and d is the anode-cathode separation. The value of β, which is related to the spatial distribution of emitting centers, the crystal structure, and the geometry morphology of emitters, reflects the ability of the emitters to enhance the applied local electric field around the probe compared to the macroscopic electric field. The FN emission behavior can be evaluated from the linearity of the curves plotting ln(J/E2) versus 1/E. Figure 4 shows the corresponding FN plots. It can be seen that, besides the noise districts, the three plots go near to a straight line. It indicates that the field emission from the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays follows the FN relationship well, and the field emission process is a barrier tunneling quantum mechanical process [30,31].

Figure 4.

Fowler-Nordheim plots of the field emission current densities of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays.

In general, FE characteristics depend on the work function and field enhancement factor (β) of emitters [32]. Both density and tip morphology influence the β value of emitters. Ordinarily, emitters with high aspect ratios exhibit a favorable FE performance due to their much higher β value. The value of β can be calculated from the slope of a FN plot (kFN) according to the following equation:

| (3) |

where φ is the work function of SnO2 (4.3 eV) [33]. By analyzing the data in Figure 4, the values of β are estimated to be 1,082, 1,378, and 1,638 as d is 100, 150, and 200 μm, respectively. It can be seen that the values of β are high enough for practical application as field emitters.

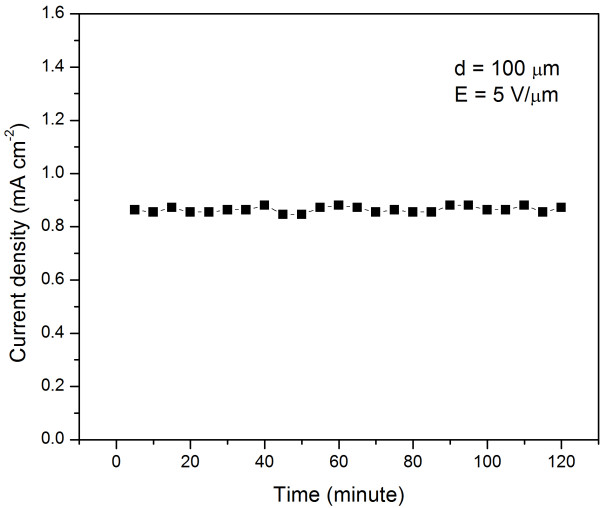

The temporal FE current stability was measured over 120 min at an anode-cathode separation of 100 μm at a fixed voltage of 500 V. The current density fluctuation is lower than 5%, as shown in Figure 5. The stability test results confirm that the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays are competent for being high-performance field emitters [34].

Figure 5.

Time dependence of the emission current of the in situ-grown SnO2 nanowire arrays. The characterization was measured at a fixed applied voltage (500 V) with an anode-cathode separation of 100 μm.

To fabricate the vertically aligned SnO2 nanowire arrays, the thickness of a Pt catalyst is of vital importance. From many experiment results, it was found that the suitable thickness of the Pt catalyst was about 2 to 10 nm. The average length of a single SnO2 nanowire in the arrays can be controlled by adjusting the reaction time. It should be noted that the SnO2 nanowire will bend if their lengths exceeded ca. 100 μm due to the force of their own gravity. Additionally, it was found that no nanowire grew on a blank silicon substrate (without Pt catalyst). This feature makes the in situ-grown method meaningful because the emitter patterns can be well controlled and designed by selective sputtering of the Pt catalyst using traditional lithography mask technology.

Conclusions

In summary, vertically aligned SnO2 nanowire arrays were deposited on a silicon substrate by an in situ-grown method. The FE properties of the SnO2 nanowire arrays were systematically studied. The FE measurement results showed that the SnO2 nanowire arrays had a low turn-on field of 1.6 to 2.8 V μm-1 at anode-cathode separations of 100 to 200 μm. The low turn-on fields can be attributed to the vertically aligned structure and the high aspect ratio of the SnO2 nanowire. Moreover, the in situ-grown method, which makes good electrical contacts between the SnO2 nanowire and the silicon substrate, improved the FE performance greatly.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ZHZ conducted all the experiments and drafted the manuscript. JW provided helpful guidance and suggestions. HDL helped in drafting the manuscript. ZMW supervised all of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Zhihua Zhou, Email: zhihuazhou@uestc.edu.cn.

Jiang Wu, Email: jiang731@gmail.com.

Handong Li, Email: hdli.phys@gmail.com.

Zhiming Wang, Email: zhmwang@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily supported by the Scientific Research Starting Foundation for Outstanding talent, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China.

References

- Gubbala S, Chakrapani V, Kumar V, Sunkara MK. Band-edge engineered hybrid structures for dye-sensitized solar cells based on SnO2 nanowires. Adv Funct Mater. 2008;18:2411–2418. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200800099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q, Huang J, Xie Z, Wang TH, Dattoli EN, Lu W. Branched SnO2 nanowires on metallic nanowire backbones for ethanol sensors application. Appl Phys Lett. 2008;92:102101. doi: 10.1063/1.2890735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sysoev VV, Goschnick J, Schneider T, Strelcov E, Kolmakov A. A gradient microarray electronic nose based on percolating SnO2 nanowire sensing elements. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3182–3188. doi: 10.1021/nl071815+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Cho J. Hard templating synthesis of mesoporous and nanowire SnO2 lithium battery anode materials. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:771–775. doi: 10.1039/b714904b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Cheng G, Cheng K, Jiang X, Du Z. The current image of single SnO2 nanobelt nanodevice studied by conductive atomic force microscopy. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:541. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Z, Wan Q, Song ZT, Feng SL. SnO2 nanowhiskers and their ethanol sensing characteristics. Nanotechnology. 2004;15:1682–1684. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/15/11/053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SM, Zhang D, Gu JJ, Xu JQ, Dong JP, Li JL. Biotemplate fabrication of SnO2 nanotubular materials by a sonochemical method for gas sensors. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:1389–1400. doi: 10.1007/s11051-009-9684-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GX, Park JS, Park MS. Growth, characterization and technological applications of semiconductor SnO2 nanotubes and In2O3 nanowires. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2009;9:1144–1147. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.C106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Guo M, Zhang M, Wang XD. Hydrothermal synthesis of SnO2 nanoflower arrays and their optical properties. Scripta Mater. 2009;61:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2009.03.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Etre AY, Reda SM. Characterization of nanocrystalline SnO2 thin film fabricated by electrodeposition method for dye-sensitized solar cell application. Appl Surf Sci. 2010;256:6601–6606. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.04.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, Yu K, Li GD, Peng DY, Zhang QX, Xu F, Bai W, Ouyang SX, Zhu ZQ. Synthesis and field emission of patterned SnO2 nanoflowers. Mater Lett. 2006;60:3109–3112. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2006.02.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li LJ, Zong FJ, Cui XD, Ma HL, Wu XH, Zhang QD, Wang YL, Yang F, Zhao JZ. Structure and field emission properties of SnO2 nanowires. Mater Lett. 2007;61:4152–4155. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2007.01.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HS, Kang SO, Kim YI. Enhancement of field emission of SnO2 nanowires film by exposure of hydrogen gas. Solid State Commun. 2006;140:495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2006.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Yu K, Li LJ, Xu JW, Shang DJ, Xu YE, Zhu ZQ. Controllable synthesis and field emission properties of SnO2 zigzag nanobelts. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2008;41:185302. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/41/18/185302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhise AB, Late DJ, Ramgir NS, More MA, Mulla IS, Pillai VK, Joag DS. Field emission investigations of RuO2-doped SnO2 wires. Appl Surf Sci. 2007;253:9159–9163. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.05.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang XS, Bando Y, Gautam UK, Ye C, Golberg D. Inorganic semiconductor nanostructures and their field-emission applications. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:509–522. doi: 10.1039/b712874f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, He XW, Chen Y. Preparation and characterization of polyacrylonitrile/antimony doped tin oxide composite nanofibers by electrospinning method. Optoelectron Adv Mat. 2010;4:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li Y, Huang X, Zhu Z. Tin oxide nanorod array-based electrochemical hydrogen peroxide biosensor. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2010;5:1177–1181. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9622-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth S, Hernandez-Ramirez F, Holmes JD, Romano-Rodriguez A. Synthesis and applications of one-dimensional semiconductors. Prog Mater Sci. 2010;55:563–627. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2010.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F, Wang SF, Cao HM, Li CZ. Synthesis and optical properties of SnO2 nanorods. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:095708. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/9/095708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng MJ, Ma L, Xu WL, Ding GQ, Shen WZ. Preparation and structural characterization of nanocrystalline SnO2 powders. Appl Phys A-mater. 2005;81:721–723. doi: 10.1007/s00339-005-3223-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima S, Oima S, Mitsuishi A, Nishimura T, Fukumoto T, Akasaka Y. Raman scattering study of ion implanted and C.W.-Laser annealed polycrystalline silicon. Solid State Commun. 1981;40:765–768. doi: 10.1016/0038-1098(81)90825-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li LJ, Yu K, Mao HB, Zhu ZQ. Photoluminescence and field-emission properties of Cu-doped SnO2 nanobelts. Appl Phys A-mater. 2010;99:865–869. doi: 10.1007/s00339-010-5620-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. Raman scattering study of rutile SnO2 nanobelts synthesized by thermal evaporation of Sn powders. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;376:103–107. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(03)00965-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M-K, Wang D-Z, Ding Y-W, Guo X-Y, Ding S, Jin H. Morphology and field emission from ZnO nanowire arrays synthesized at different temperature. Mat Sci Eng A-struct. 2007;452-453:417–421. [Google Scholar]

- He JH, Wu TH, Hsin CL, Li KM, Chen LJ, Chueh YL, Chou LJ, Wang ZL. Beaklike SnO2 nanorods with strong photoluminescent and field-emission properties. Small. 2006;2:116–120. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JB, Li K, Zhong XL, Zhou YC, Fang XS, Tang CC, Bando Y. Considerable enhancement of field emission of SnO2 nanowires by post-annealing process in oxygen at high temperature. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2009;4:1135–1140. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9367-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Chen G, Li Z, Deng S, Xu N. Quantum-mechanical investigation of field-emission mechanism of a micrometer-long single-walled carbon nanotube. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92:106803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.106803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YA, Lin JY, Guo TL. Fabrication and properties of film-under-gate field emission arrays with SnO2 emitters for flat lamp. Appl Surf Sci. 2010;257:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.06.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Heer WA, Châtelain A, Ugarte D. A carbon nanotube field-emission electron source. Science. 1995;270:1179–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li LA, Cheng SH, Li HD, Yu Q, Liu JW, Lv XY. Effect of nitrogen on deposition and field emission properties of boron-doped micro- and nano-crystalline diamond films. Nano-Micro Lett. 2010;2:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sheini FJ, Singh J, Srivasatva ON, Joag DS, More MA. Electrochemical synthesis of Cu/ZnO nanocomposite films and their efficient field emission behaviour. Appl Surf Sci. 2010;256:2110–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2009.09.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Chu PK, Di Z, Zhang M, Liu W, Lin C, Fan J, Wu X. Vacuum electron field emission from SnO2 nanowhiskers annealed in N2 and O2 atmospheres. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;88:013109. doi: 10.1063/1.2161573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue XY, Li LM, Yu HC, Chen YJ, Wang YG, Wang TH. Extremely stable field emission from AlZnO nanowire arrays. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;89:043118. doi: 10.1063/1.2236288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]