Abstract

Recent investigations have demonstrated that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is associated with a range of impulsive behaviors (e.g., risky sexual behavior and antisocial behavior). The purpose of the present study was to extend extant research by exploring whether emotion dysregulation explains the association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors. Participants were an ethnically diverse sample of 206 substance use disorder (SUD) patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Results demonstrated an association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors, with SUD patients with PTSD reporting significantly more impulsive behaviors than SUD patients without PTSD (in general and when controlling for relevant covariates). Further, emotion dysregulation was found to fully mediate the relationship between PTSD and impulsive behaviors. Results highlight the relevance of emotion dysregulation to impulsive behaviors and suggest that treatments targeting emotion dysregulation may be useful in reducing impulsive behaviors among SUD patients with PTSD.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, emotion regulation, impulsivity, impulsive behaviors, risky behavior, risk-taking, substance use disorders

1. Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder characterized by the development and persistence of re-experiencing, avoidant, and hyperarousal symptoms following direct or indirect exposure to a potentially traumatic event (Blake et al., 1990). PTSD is a serious clinical concern, associated with considerable functional impairment (Kessler & Frank, 1997) and high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Kessler et al., 1995). Furthermore, individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been found to be at-risk for a wide range of impulsive behaviors, including substance misuse (Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004; Jakupcak et al., 2010; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Ouimette, Read, & Brown, 2005), antisocial behaviors (Booth-Kewley, Larson, High-McRoy, Garland, & Gaskin, 2010; Resnick, Foy, Donahoe, & Miller, 1989), interpersonal aggression (Galovski & Lyons, 2004; Monson, Fredman, & Dekel, 2010; Orcutt, King, & King, 2003), binge eating and purging (Gleaves, Eberenz, & May, 1998; Holzer, Uppala, Wonderlich, Crosby, & Simonich, 2008), deliberate self-harm (Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, 2002; Sacks, Flood, Dennis, Hertzberg, & Beckham, 2008), and risky sexual behavior (Rosenberg et al., 2001). Despite evidence for elevated rates of impulsive behaviors within PTSD, however, few studies have examined the factors that may underlie the association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors.

One mechanism worth examining in this regard is emotion dysregulation. As defined here, emotion dysregulation is a multi-faceted construct involving: (a) a lack of awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions; (b) the inability to control behaviors when experiencing emotional distress; (c) lack of access to adaptive strategies for modulating the duration and/or intensity of aversive emotional experiences; and (d) an unwillingness to experience emotional distress as part of pursuing meaningful activities in life (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Theoretical and empirical literature highlights the role of emotion dysregulation in PTSD (Cloitre et al., 2002; Ehring & Quack, 2010; McDermott, Tull, Gratz, Daughters, & Lejuez, 2009; Tull, Barrett, McMillan, & Roemer, 2007; Weiss, Tull, Davis, Dehon, Fulton, & Gratz, in press). Specifically, PTSD has been found to be positively associated with overall emotion dysregulation and the specific dimensions of lack of emotional acceptance, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors and controlling impulsive behaviors when upset, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity (Ehring & Quack, 2010, Tull et al., 2007). Furthermore, research provides evidence of heightened emotion dysregulation among individuals with (vs. without) PTSD, both in general and among substance use disorder (SUD) patients in particular. For example, emotion dysregulation was found to reliably distinguish between cocaine-dependent patients with and without a probable PTSD diagnosis (above and beyond both anxiety symptom severity and anxiety sensitivity; McDermott et al., 2009).

A small but growing body of research also provides support for the role of emotion dysregulation in a variety of impulsive behaviors. For example, Leith and Baumeister (1996) found that impulsive behavior is more likely to occur following the experience of negative moods characterized by high levels of arousal (which may be more difficult to regulate; Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005). Similarly, emotion dysregulation has been found to be heightened among SUD patients with (vs. without) a history of deliberate self-harm (DSH; Gratz & Tull, 2010a), as well as to distinguish women with frequent DSH from those without a history of DSH (above and beyond several other well-established risk factors for DSH; Gratz & Roemer, 2008). Likewise, Whiteside and colleagues (2007) found that emotion dysregulation accounted for a significant amount of the variance in binge eating (above and beyond gender, food restriction, and over-evaluation of weight and shape). Finally, Messman-Moore, Walsh, and DiLillo (2010) demonstrated that emotion dysregulation was significantly positively associated with past 6-month risky sexual behavior within a nonclinical sample of college women.

Although the aforementioned findings provide support for a relationship between emotion dysregulation and both PTSD and impulsive behaviors, additional research is needed to explore whether emotion dysregulation underlies the association between PTSD and impulsive behavior. Consequently, the goal of the present study was to extend extant research by examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors, as well as the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between PTSD and past engagement in impulsive behaviors. In examining these associations, one population that may be especially important to study is patients with SUDs, given evidence of (a) heightened rates of PTSD among SUD patients (compared to non-substance users; Brady et al., 2004); (b) high levels of impulsive behaviors among SUD patients with co-occurring PTSD (Hoff, Beam-Goulet, & Rosenheck, 1997; Najavits et al., 2007; Ouimette, Finney, & Moos, 1999; Parrott, Drobes, Saladin, Coffey, & Dansky, 2003); and (c) elevated levels of emotion dysregulation among SUD patients (Fox, Axelrod, Paliwal, Sleeper, & Sinha, 2007; Fox, Hong, & Sinha, 2008; McDermott et al., 2009).

Consistent with past research (Ehring & Quack, 2010; McDermott et al., 2009; Tull et al., 2007), we hypothesized that SUD patients with (vs. without) PTSD would report higher levels of both emotion dysregulation and impulsive behaviors. Furthermore, we predicted that emotion dysregulation would be significantly positively associated with impulsive behaviors. Finally, given literature suggesting that emotion dysregulation may underlie a variety of impulsive behaviors (see, e.g., Gratz & Roemer, 2008; Safer et al., 2009; for a review, see Gratz & Tull, 2010b), we hypothesized that emotion dysregulation would mediate the relationship between PTSD and impulsive behaviors.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 206 SUD patients consecutively admitted to a residential SUD treatment facility in central Mississippi. Participants were predominantly male (n = 130, 63%), and ranged in age from 18 to 61 (M age = 35.51, SD = 10.29). In terms of racial/ethnic background, 56% of participants self-identified as White, 36% as Black/African American, 4% as Native American, 2% as Latino/Latina, and 2% as another racial/ethnic background. Most participants reported an annual income under $20,000 (n = 128, 63%) and no higher than a high school education (n = 126, 61%).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Clinical Interviews

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake, Weathers, Nagy, & Kaloupek, 1995; Blake et al., 1990), the most widely used PTSD measure (Elhai, Gray, Kashdan, & Franklin, 2005), was used to assess for a current diagnosis of PTSD. This structured diagnostic interview assesses the frequency and intensity of the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms (plus eight associated symptoms). Frequency items are rated from 0 (never or none/not at all) to 4 (daily or almost every day or more than 80%). Intensity items are rated from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme). The CAPS has adequate interrater reliability (.92–.99), internal consistency (.73–.85), and convergent validity with the SCID-IV and other established measures of PTSD (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). In addition, the robust psychometric properties of the CAPS have been supported in a variety of combat and civilian (including inpatient SUD) samples, as well as across different racial-ethnic group (e.g., Blake et al., 1990; Brown, Stout, & Mueller, 1996; Shalev, Freedman, Peri, Brandes, & Sahar, 1997; Weathers et al., 2001). For the purposes of the present study, and consistent with past research (see Blanchard, Hickling, Taylor, & Forneris, 1995), we utilized the Item Severity ≥ 4 (ISEV4) rule, which requires that at least one reexperiencing, three avoidance/emotional numbing, and two hyperarousal symptoms have a severity rating (frequency + intensity) of ≥ 4 to establish current PTSD (see Weathers, Ruscio, & Keane, 1999). Internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (α = .95).

Given the lack of empirically-supported measures of impulsive behaviors, we utilized the impulsive behaviors criterion (Item 85) of the borderline personality disorder (BPD) module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Sickel, & Young, 1996). The DIPD-IV is well-established and widely-used diagnostic interview of Axis II personality disorders with good inter-rater and test-retest reliability (Zanarini et al., 2000). The impulsive behaviors item of the BPD module assesses the presence of clear-cut patterns of a variety of impulsive behaviors in the past two years. Specifically, participants are asked about patterns of engagement in 12 impulsive behaviors, including impulsive sexual behavior, binge eating and/or purging, spending sprees, substance abuse, and antisocial behavior, among others. Only those behaviors endorsed by the participant as occurring regularly over the past two years are considered present and scored a 1, with behaviors that occurred infrequently or never scored a 0. Scores for each of the 12 behaviors are then summed to create a continuous variable reflecting the total number of different impulsive behaviors regularly engaged in during the past two years. Although the impulsive behaviors assessed with this item are considered to be relevant to a BPD diagnosis, they have also been found to be relevant to PTSD (e.g., Booth-Kewley et al., 2010; Gleaves et al., 1998; Kessler et al., 1995; Monson et al., 2010; Rosenberg et al., 2001). Internal consistency for this variable within this sample was adequate (α = .72).

Finally, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) was used to assess for current Axis I disorders other than PTSD. Co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders were examined as potential covariates. All interviews were administered by post-baccalaureate or doctoral-level clinical assessors trained to reliability with the principal investigator (MTT).

All interviews were reviewed by a PhD level clinician (MTT or KLG), with diagnoses confirmed in consensus meetings.

2.2.2. Measure of Emotion Dysregulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report measure that assesses individuals’ typical levels of emotion dysregulation across six domains: non-acceptance of negative emotions, inability to engage in goal-directed behaviors when distressed, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed, limited access to emotion regulation strategies perceived as effective, lack of emotional awareness, and lack of emotional clarity. The DERS has been found to demonstrate good test-retest reliability (ρI = .88, p < .01) and adequate construct and predictive validity (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Gratz & Tull, 2010b). Further, the DERS has been found to predict performance on behavioral measures of emotion regulation and the willingness to experience emotional distress (for a review, see Gratz & Tull, 2010b). Items were recoded so that higher scores indicate greater emotion dysregulation, and a sum was calculated. Internal consistency in the current sample was good (α = .89).

2.2.3. Demographic Information

All participants completed a demographics form assessing gender, age, racial/ethnic background, marital status, education, and income in the past year. These characteristics were examined as potential covariates.

2.3. Procedure

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board. Data were collected as part of a larger ongoing study examining predictors of residential SUD treatment dropout. To be eligible for inclusion in the study, participants were required to have: (a) obtained a Mini-Mental Status Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of ≥ 24; and (b) exhibited no current psychotic disorders (as determined by the SCID-I/P). Eligible participants were recruited for this study no sooner than 72 hours after entry in the facility (to limit the possible interference of withdrawal symptoms on study engagement). Those who met inclusion criteria were provided with information about study procedures and associated risks, following which written informed consent was obtained. All patients participated in this study within their first two weeks of treatment.

The study took part in two sessions conducted on separate days (to limit participant burden). In the first session, participants were interviewed with the CAPS, the BPD module of the DIPD, and the SCID-I/P. In the second session (occurring approximately 4 days after the first session), participants were asked to complete a battery of questionnaires that included the DERS. Participants received $15 for completing each session.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

In order to identify covariates for subsequent analyses, analyses were first conducted to examine the relationships between impulsive behaviors and demographic factors (i.e., age, gender, racial/ethnic background, income, education, relationship status, and employment) and current Axis I diagnoses. Given the small number of participants in several of the income, marital status, education, employment, and racial/ethnic categories, these variables were collapsed into dichotomous variables of over (52%) versus under (48%) $10,000 per year; single (70%) versus in a committed relationship/married (30%); high school diploma or less (61%) versus education beyond high school (39%); employed (29%) versus unemployed (71%); and White (56%) versus Non-White (44%). No differences in impulsive behaviors emerged as a function of gender, marital status, racial/ethnic background, education, employment, or income (ts < 1.02, ps > .05). However, there were significant age differences in the number of impulsive behaviors, with younger participants reporting significantly more impulsive behaviors than older participants (r = −.30, p < .01). Furthermore, results demonstrated significant differences in impulsive behaviors as a function of the presence of current major depressive disorder (MDD), panic disorder (PD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), with participants with (vs. without) MDD, PD, and GAD reporting a greater number of impulsive behaviors (ts > 2.37, ps < .05). Consequently, age, MDD, PD, and GAD were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

3.2. Primary Analyses

Based on CAPS data, 60 participants (29%) met diagnostic criteria for current PTSD. In addition, participants reported a clear-cut pattern of impulsive behavior in 5.28 areas on average (SD = 2.84). Descriptive data, as well as intercorrelations between the primary variables of interest, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive data and intercorrelations for primary variables of interest

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSD status | (.95) | .39** | .39** | .23** |

| 2. DERS total score | .27** | (.89) | .99** | .31** |

| 3. DERS total score (with IMPULSE subscale removed) | .27** | .98** | (.92) | .27** |

| 4. Impulsive behavior | .17* | .23** | .20** | (.72) |

|

| ||||

| Mean | --- | 86.32 | 72.30 | 5.28 |

| SD | --- | 26.25 | 21.43 | 2.84 |

Note. PTSD status = CAPS PTSD status (0 = absent, 1 = present). DERS=Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. IMPULSE = Difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed subscale of the DERS. Coefficient alphas appear in parentheses. Zero-order correlations appear above the diagonal and partial correlations (controlling for age, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder) appear below the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .01.

To examine between-group differences in impulsive behaviors and emotion dysregulation, we conducted two one-way (PTSD vs. non-PTSD) analyses of covariance (controlling for age, MDD, PD, and GAD). Results revealed significant between-group differences in both impulsive behaviors (F [1, 200] = 5.92, ηp2 = .03, p < .05) and emotion dysregulation (F [1, 200] = 15.14, ηp2 = .07, p < .01), with patients with PTSD reporting significantly more impulsive behaviors (M = 6.32 ± 2.75) and greater emotion dysregulation (M = 102.14 ± 26.01) than those without PTSD (M = 4.86 ± 2.78 and M = 79.82 ± 23.51, respectively).1 Likewise, emotion dysregulation was significantly correlated with impulsive behaviors (r = .31, p < .01).

Following procedures outlined by Preacher and Hayes (2004), analyses were conducted to examine whether emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between PTSD status (present vs. absent) and impulsive behaviors (outcome) when controlling for age, MDD, GAD, and PD. The bootstrap method was used for estimating the standard errors of parameter estimates and the bias-corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effects (see MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). The bias-corrected confidence interval is based on a non-parametric re-sampling procedure that has been recommended when estimating confidence intervals of the mediated effect due to the adjustment it applies over a large number of bootstrapped samples (Efron, 1987). The mediated effect is significant if the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). In this study, 5000 bootstrap samples were used to derive estimates of the indirect effect. Also of note, all coefficients are reported as unstandardized estimates.

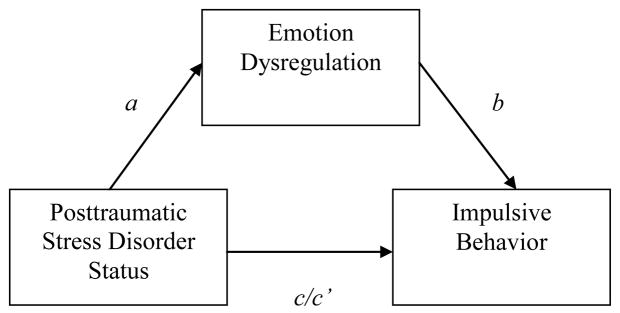

As shown in Table 2, mediation analyses revealed that PTSD status was significantly associated with emotion dysregulation (B = 14.70, SE = 3.78; t = 3.89, p < .01), demonstrating a direct effect between PTSD and emotion dysregulation (see Figure 1). PTSD status was also significantly associated with impulsive behaviors (B = 1.05; SE = .43; t = 2.43, p < .05). Furthermore, the indirect effect of PTSD status on impulsive behaviors through the pathway of emotion dysregulation (B = .34; SE = .15, 95% CI = .09–.69) was also significant. Notably, the direct effect linking PTSD status with impulsive behaviors was not significant after controlling for emotion dysregulation (B = .72; t = 1.64, p = .10), suggesting that emotion dysregulation fully mediated the association between PTSD status and impulsive behaviors. The full model accounted for 22% of the variance in impulsive behaviors, F (6, 199) = 9.06, p < .01.

Table 2.

Summary of mediation analyses (5000 bootstrap samples)

| Independent variable

|

Mediating variable

|

Dependent variable

|

Effect of IV on M

|

Effect of M on DV

|

Direct Effect

|

Indirect Effect

|

Total Effect

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (IV) | (M) | (DV) | (a) | (b) | (c′) | (a × b) | 99% CI | (c) |

| PTSD status | DERS | DIPD Impulsivity | 14.701** | 0.022** | 0.724 | 0.335* | 0.091–0.689 | 1.054* |

Note. PTSD status = CAPS PTSD status (0 = absent, 1 = present); DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DIPD Impulsivity = Impulsive behaviors from the BDP module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. All coefficients are reported as unstandardized estimates.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Proposed mediational model depicting total (c), direct (c′), and indirect effects (a × b) of PTSD status on impulsive behavior.

Given some conceptual overlap between one dimension of the proposed mediator (i.e., difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed [DERS-IMPULSE]) and the dependent variable (i.e., impulsive behavior), we re-ran analyses excluding the DERS-IMPULSE subscale from the overall DERS score. Findings remain the same when this subscale is omitted from the total DERS score. Specifically, mediation analyses revealed a significant association between PTSD status and emotion dysregulation (B = 12.24, SE = 3.09; t = 3.97, p < .01), demonstrating a direct effect of PTSD on emotion dysregulation. Furthermore, the indirect effect of PTSD status on impulsive behaviors through the pathway of emotion dysregulation (B = 1.05; SE = .43, 95% CI = .06–.62) was also significant. Finally, the direct effect linking PTSD status with impulsive behaviors was not significant after controlling for emotion dysregulation (B = .78; t = 1.75, p = .08). As such, these findings suggest that the association between emotion dysregulation and impulsive behaviors, as well as its mediating role in the association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors, is not driven solely by the dimension of emotion dysregulation related to difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when distressed.

Finally, given past findings of an association between traumatic event exposure and impulsivity (e.g., Braquehais, Oquendo, Baca-García, & Sher, 2010; Zlotnick et al., 1997), and in an effort to ensure that the observed relationship between PTSD and impulsive behaviors is specific to PTSD (vs. traumatic exposure per se), exploratory analyses were conducted to examine (a) the extent to which traumatic exposure in general was associated with impulsive behaviors, and (b) the extent to which this accounted for the observed relationship between PTSD and impulsive behaviors within this sample. Results indicated no significant association between the number of potentially traumatic events reported on the CAPS and impulsive behaviors (r = .09, p > .05). In addition, although findings revealed a significant difference in impulsive behaviors as a function of whether or not participants reported a Criterion A traumatic event on the CAPS (F [1, 204] = 4.07, p < .05), this difference did not remain significant when controlling for PTSD status (F [1, 203] = 0.45, p > .05). Together, these findings increase confidence that the observed association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors is due to the presence of a PTSD diagnosis, rather than the severity of traumatic exposure alone.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to extend extant research by exploring the role of emotion dysregulation in the relation between PTSD and impulsive behaviors within a sample of SUD patients. As predicted, and consistent with past research (e.g., Booth-Kewley et al., 2010; Gratz & Roemer, 2008; Tull et al., 2007), significant associations were found between all of the variables of interest. Specifically, SUD patients with PTSD reported greater emotion dysregulation and more impulsive behaviors than those without PTSD. Furthermore, and consistent with hypotheses, emotion dysregulation fully mediated the relationship between PTSD status and impulsive behaviors, suggesting that emotion dysregulation explains the association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that emotion dysregulation is an underlying mechanism of several specific impulsive behaviors (Gratz & Roemer, 2008; Messman-Moore et al., 2010; Safer et al., 2009; Stice, 2002).

Findings of the present study speak to the relevance of emotion dysregulation to impulsive behaviors. Previous investigations have found that personality traits traditionally thought to be associated with impulsive behaviors (e.g., trait impulsivity) may in fact not be directly related to impulsive behaviors (see Reynolds, Ortengren, Richards, & de Wit, 2006 for a review). Furthermore, although recent investigations have sought to clarify the multidimensional nature of impulsivity and identify the particular dimensions most closely associated with impulsive behaviors (e.g., Whiteside & Lynam, 2001), many dimensions of impulsivity are not associated with and/or predictive of impulsive behavior. Notably, negative urgency (i.e., the tendency to act impulsively when experiencing negative affect), a trait closely related to emotion dysregulation (Cyders & Smith, 2007, 2008), has demonstrated the strongest associations with several impulsive behaviors (e.g., bulimic symptoms and compulsive buying; Billieux, Rochat, Rebetez, & der Linden, 2008; Fischer, Smith, & Anderson, 2003), providing further evidence for the role of emotion dysregulation in impulsive behaviors. Together, these findings suggest that impulsive behaviors may be more strongly related to maladaptive ways of responding to emotions or difficulties controlling behaviors in the context of emotional distress than a trait disposition to act without adequate forethought as to the consequences of actions (i.e., impulsivity).

Specifically, PTSD-SUD patients with high levels of emotion dysregulation may be more likely to engage in impulsive behaviors in an attempt to alleviate or distract themselves from emotional states perceived as aversive, such as anger, fear, shame, or sadness. Alternatively, the short-term pleasure that may be associated with certain impulsive behaviors may function to counter or distract from unpleasant emotional states that an individual is unwilling to approach, tolerate, or accept. It is also possible that heightened levels of emotion dysregulation may increase the risk for maladaptive behavioral responses in general or interfere with the ability to control one’s behaviors (see Linehan, 1993).

Although the present study adds to the growing body of literature on PTSD and impulsive behavior, several limitations must be taken into account. First, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the data limits our ability to determine the exact nature and direction of the relationships of interest. For example, although a growing body of theoretical and empirical literature suggests that emotion dysregulation may underlie impulsive behaviors (Gratz & Tull, 2010b), it is also possible that this association is bidirectional and that regular engagement in impulsive behaviors may lead to or exacerbate emotion dysregulation. Additionally, it remains unclear if a PTSD diagnosis increases the risk for impulsive behaviors. Prospective studies are needed to examine the precise nature and direction of the relationships between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors.

In addition, studies utilizing experience sampling methods may inform whether emotion dysregulation immediately precedes engagement in impulsive behavior, as well as whether engagement in impulsive behavior results in the reduction of negative affect, suggesting an emotion regulating function of impulsive behaviors. Future research should also examine the extent to which emotion dysregulation contributes to impulsive behaviors among PTSD-SUD patients above and beyond trait impulsivity (speaking to the relative and unique contributions of each of these mechanisms to impulsive behaviors within this population).

An additional limitation is the exclusive reliance on a self-report measure of emotion dysregulation, responses to which may be influenced by an individual’s willingness and/or ability to report accurately on emotional responses. However, it is important to note that the measure of emotion dysregulation utilized in this study is strongly correlated with behavioral measures of emotion regulation and the willingness to experience emotional distress (see Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez, & Gunderson, 2006; Gratz & Tull, 2010b). Nonetheless, future studies would benefit from the use of non self-report (e.g., behavioral, physiological) measures of emotion dysregulation. Additionally, although our measure of impulsive behaviors was drawn from a well-established and empirically-validated diagnostic interview of personality disorders (providing the opportunity for interviewers to clarify the severity and extent of impulsive behaviors endorsed by participants, and thereby serving as an improvement over existing self-report checklists of impulsive behaviors), this item does not have empirical support as a measure of impulsive behaviors on its own. Notably, existing measures of impulsive behaviors used in the literature tend to suffer from a similar limitation (see Peñas-Lledó, de Dios Fernández, & Waller, 2004), with little empirical support and a reliance on face validity. Nonetheless, research on the factors associated with impulsive behaviors would benefit from the development and validation of a comprehensive measure of impulsive behaviors. Finally, our findings cannot be assumed to generalize to non-SUD populations and require replication across a more diverse group of PTSD patients.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study add to the growing body of literature demonstrating the relevance of emotion dysregulation to maladaptive behaviors among individuals with co-occurring PTSD-SUD. Specifically, findings suggest that the association between PTSD and impulsive behaviors among SUD patients may be explained by emotion dysregulation. As such, the findings from this study highlight a potential target for interventions aimed at reducing impulsive behaviors among PTSD-SUD patients, suggesting the utility of teaching SUD patients with PTSD skills for regulating their emotions. Of note, treatments that include emotion regulation skills training have been found to benefit patients with PTSD, including Cloitre et al.’s (2002) Skills Training in Affect and Interpersonal Regulation/Prolonged Exposure. There is also recent evidence that Dialectical Behavior Therapy may be of benefit to patients with PTSD (Steil, Dyser, Priebe, Kleindienst, & Bohus, 2011). However, the extent to which these treatments reduce impulsive behaviors among patients with a PTSD-SUD diagnosis remains unclear. Nonetheless, findings of reductions in impulsive behaviors following a brief emotion regulation group therapy among patients with borderline personality pathology (Gratz & Tull, 2011) suggest that such interventions may indeed reduce impulsive behaviors among at-risk populations. Future investigations are needed that examine the utility of these treatments in reducing impulsive behavior among SUD patients with PTSD. Furthermore, although there is some evidence that an empirically-supported integrated PTSD and substance abuse treatment (i.e., Najavits’s [2002] Seeking Safety) may reduce impulsive behavior (e.g., risky sexual behavior; Hien et al., 2010), future studies are needed to examine whether this treatment reduces impulsive behavior through an improvement in emotion regulation.

Highlights.

Substance use disorder patients with PTSD exhibit more impulsive behaviors.

Emotion dysregulation is positively associated with impulsive behavior.

Emotion dysregulation explains the association between PTSD and impulsive behavior.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided in part by R21 DA022383 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health awarded to the second author (MTT). The authors would like to thank Bettye Van Norman, Michael McDermott, Melissa Soenke, Sarah Anne Moore, Rachel Brooks, and Jessica Fulton for their assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Results remained the same in strength and direction when the covariates were removed from the analyses.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nicole H. Weiss, Jackson State University, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Matthew T. Tull, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Andres G. Viana, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

Michael D. Anestis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, USA

Kim L. Gratz, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA

References

- Billieux J, Rochat L, Rebetez M, Van der Linden M. Are all facets of impulsivity related to self-reported compulsive buying behavior? Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:1432–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy L, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale. Boston: National Center for PTSD- Behavioral Science Division; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Forneris CA. Effects of varying scoring rules of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:471–475. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00064-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth-Kewley S, Larson GE, Highfill-McRoy RM, Garland CF, Gaskin TA. Factors associated with antisocial behavior in combat veterans. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:330–337. doi: 10.1002/ab.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Braquehais MD, Oquendo MA, Baca-García E, Sher L. Is impulsivity a link between childhood abuse and suicide? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Stout RL, Mueller T. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse relapse among women: A pilot study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, Han H. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1067–1074. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1987;82:171–200. doi: 10.1080/10618600.2020.1714633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Quack D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: The role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Gray MJ, Kashdan TB, Franklin C. Which instruments are most commonly used to assess traumatic event exposure and posttraumatic effects?: A survey of traumatic stress professionals. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:541–545. doi: 10.1002/jts.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Unpublished measure. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. Structured clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders–Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Anderson KG. Clarifying the role of impulsivity in bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:406–411. doi: 10.1002/eat.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Axelrod SR, Paliwal PP, Sleeper JJ, Sinha RR. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha RR. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski T, Lyons JA. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: A review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:477–501. [Google Scholar]

- Gleaves DH, Eberenz KP, May MC. Scope and significant of posttraumatic symptomatology among women hospitalized for an eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24:147–156. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<147::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. The relationship between emotion dysregulation and deliberate self-harm among female undergraduate students at an urban commuter university. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2008;37:14–25. doi: 10.1080/16506070701819524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Rosenthal M, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, Gunderson JG. An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:850–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments. In: Baer RA, editor. Assessing mindfulness and acceptance: Illuminating the processes of change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2010b. pp. 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. The relationship between emotion dysregulation and deliberate self-harm among inpatient substance users. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010a;34:544–553. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. Extending research on the utility of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:316–326. doi: 10.1037/a0022144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Campbell AN, Killeen T, Hu MC, Hansen C, Jiang H, et al. The impact of trauma-focused group therapy upon HIV sexual risk behaviors in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network “Women and trauma” multi-site study. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:421–430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9573-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff RA, Beam-Goulet J, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorder as a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus infection in a sample of veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1997;185:556–560. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer SR, Uppala S, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Simonich H. Mediational significance of PTSD in the relationship of sexual trauma and eating disorders. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Kaysen D, Hunt S, Simpson T. PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans seeking post-deployment VA health care. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:840–843. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Frank RG. The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 1997;27:861–873. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–103. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott MJ, Tull MT, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW. The role of anxiety sensitivity and difficulties in emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder among crack/cocaine dependent patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Walsh KL, DiLillo D. Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Fredman SJ, Dekel R. Posttraumatic stress disorder in an interpersonal context. In: Beck J, Beck J, editors. Interpersonal processes in the anxiety disorders: Implications for understanding psychopathology and treatment. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 179–208. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM. Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Butler SF, Barber JP, Thase ME, Crits-Christoph P. Six-month treatment outcomes of cocaine-dependent patients with and without PTSD in a multisite national trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:353–361. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, King LA, King DW. Male-perpetrated violence among Vietnam veteran couples: Relationships with veteran’s early life characteristics, trauma history, and PTSD symptomatology. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:381–390. doi: 10.1023/A:1024470103325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Finney JW, Moos RH. Two-year posttreatment functioning and coping of substance abuse patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Read J, Brown PJ. Consistency of retrospective reports of DSM-IV Criterion A traumatic stressors among substance use disorder patients. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:43–51. doi: 10.1002/jts.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Drobes DJ, Saladin ME, Coffey SF, Dansky BS. Perpetration of partner violence: Effects of cocaine and alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1587–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñas-Lledó E, de Dios Fernández J, Waller G. Association of anger with bulimic and other impulsive behaviours among non-clinical women and men. European Eating Disorders Review. 2004;12:392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Foy DW, Donahoe CP, Miller EN. Antisocial behavior and post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1989;45:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198911)45:6<860::aid-jclp2270450605>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Personality and behavioral measures. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Trumbetta SL, Mueser KT, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Vidaver RM, Metzger DS. Determinants of risk behavior for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in people with severe mental illness. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:263–271. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks MB, Flood AM, Dennis MF, Hertzberg MA, Beckham JC. Self-mutilative behaviors in male veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:487–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer DL, Telch CF, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T. Predicting PTSD in trauma survivors: Prospective evaluation of self-report and clinician-administered instruments. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:558–564. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steil R, Dyser A, Priebe K, Kleindienst N, Bohus M. Dialectical behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse: A pilot study of an intensive residential treatment program. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:102–106. doi: 10.1002/jts.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Barrett HM, McMillan ES, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ruscio A, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JT. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Davis LT, Dehon EE, Fulton JJ, Gratz KL. Examining the association between emotion regulation difficulties and probable posttraumatic stress disorder within a sample of African Americans. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.621970. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside U, Chen E, Neighbors C, Hunter D, Lo T, Larimer M. Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Young L. Unpublished measure. Boston, MA: McLean Hospital; 1996. Diagnostic interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: II. Reliability of Axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Shea T, Recupero P, Bidadi K, Pearlstein T, Brown P. Trauma, dissociation, impulsivity, and self-mutilation among substance abuse patients. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:650–654. doi: 10.1037/h0080263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]