Abstract

Growth factor signaling coupled to activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway plays a crucial role in the regulation of cell proliferation and survival. The key regulatory kinase of Akt has been identified as mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2), which functions as the PI3K-dependent Ser-473 kinase of Akt. This kinase complex is assembled by mTOR and its essential components rictor, Sin1 and mLST8. The recent genetic screening study in Caenorhabditis elegans has linked a specific point mutation of rictor to an elevated storage of fatty acids that resembles the rictor deficiency phenotype. In our study, we show that in mammalian cells the analogous single rictor point mutation (G934E) prevents the binding of rictor to Sin1 and the assembly of mTORC2, but this mutation does not interfere with the binding of the rictor-interacting protein Protor. A substitution of the rictor Gly-934 residue to a charged amino acid prevents formation of the rictor/Sin1 heterodimer. The cells expressing the rictor G934E mutant remain deficient in the mTORC2 signaling, as detected by the reduced phosphorylation of Akt on Ser-473 and a low cell proliferation rate. Thus, although a full length of rictor is required to interact with its binding partner Sin1, a single amino acid of rictor Gly-934 controls its interaction with Sin1 and assembly of mTORC2.

Keywords: cell signaling, mTORC2, Akt, complex assembly, kinase

The processes of cell growth and proliferation are tightly controlled by growth factor signaling pathways deregulated in many human cancers (Zhang and Yee, 2000; Gross and Yee, 2003; Schlessinger and Lemmon, 2003; Citri and Yarden, 2006). Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase and its downstream effector Akt, also known as protein kinase B, are the key players of growth factor-regulated pathway implicated in cell proliferation and survival (Shaw and Cantley, 2006).

The binding of growth factor ligand to its cognate receptor leads to the activation of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase, which functions as a kinase of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-diphosphates and generates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphates (Cantley, 2002). Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphates initiate recruitment of Akt to plasma membrane via their plekstrin homology domain (Bellacosa et al., 1998). At the plasma membrane, Akt gets phosphorylated on Thr-308 and Ser-473 sites required for its full activation (Pearce et al., 2010). The Thr-308 site residing within the activation loop of the Akt kinase domain is phosphorylated by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (Alessi et al., 1997; Stephens et al., 1998; Bayascas, 2008). The mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) phosphorylates the regulatory hydrophobic Ser-473 site on Akt (Sarbassov et al., 2005a, b; Frias et al., 2006). It has been reported that following the DNA damage conditions the DNA protein kinase also phosphorylates Akt on Ser-473 (Bozulic et al., 2008).

Originally, mTOR was discovered as a target for the lypophilic macrolide rapamycin. Rapamycin is known to carry anti-proliferative and growth-inhibitory effects that is attributed to its specific targeting and inhibition of mTOR, a key kinase of the essential and highly conserved signaling pathway (Sarbassov et al., 2005a). mTOR forms a core complex by its interacting proteins mLST8 and DEPTOR; this core complex forms two multi-protein complexes. The binding of raptor to the core mTOR complex defines the mTOR complex 1, which relays growth factor and nutritional cues to protein synthesis machinery by phosphorylating its two well-known substrates, S6K and 4EBP1. The second mTOR complex (mTORC2) is assembled by the binding of rictor and Sin1 to the mTOR core complex. This kinase complex phosphorylates the hydrophobic Ser-473 site on Akt, and as the component of growth factor signaling regulates cell proliferation and survival (Guertin and Sabatini, 2005, 2007). Besides Akt, mTORC2 is known to phosphorylate other members of the AGC kinase family, including PKCα and SGK1 (Pearce et al., 2010, 2011). The recently identified rictor-interacting protein Protor, as a component of mTORC2, has been shown to be important in the regulation of SGK1 by mTORC2 (Woo et al., 2007; Pearce et al., 2007, 2010, 2011).

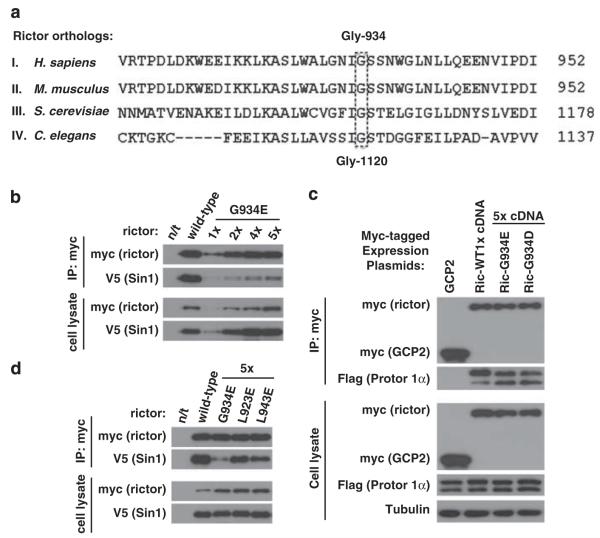

Rictor is a conserved protein in all eukaryotes (Sarbassov et al., 2004). The point mutation of rictor in Caenorhabditis elegans resembling the rictor deficiency phenotype represents the G1120E substitution mutation (Jones et al., 2009; Soukas et al., 2009) of the highly conserved amino acid as detected by a sequence alignment, including the yeast and human rictor orthologs (Figure 1a). This conserved residue corresponds to the human rictor glycine at position 934.

Figure 1.

The rictor Gly-934 amino-acid residue is crucial for the rictor/Sin1 interaction. (a) Alignment of the rictor ortholog sequences. The C. elegans rictor Gly-1120 site aligns with the human rictor Gly-934 residue. The rictor orthologs carrying the following accession numbers have been analyzed: I. H. sapiens (AAS79796.1), II. M. musculus (NP_084444.3), III. S. cerevisiae (DAA07754.1) and IV. C. elegans (F29C12.3). The rictor sequences were obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database and were analyzed by the BLAST protein alignment tool. (b) Rictor G934E mutation interferes with rictor/Sin1 interaction. The wild-type or mutated myc-tagged rictor plasmid was transiently co-expressed with the Sin1-V5 plasmid in 293T cells. In order to overcome the low expression of the mutant form, the cDNA plasmid levels applied for transfection were increased as indicated. Following 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed as described previously (Chen et al., 2011) in the 40 mm 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.5), 120 mm NaCl, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid(EDTA), 10 mm Na-pyrophosphate, 10 mm Na-glycerophosphate, 50 mm NaF and 1% Triton X-100 buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The scraped lysates were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C to complete lysis. The soluble fractions of cell lysates were isolated by centrifugation at 16 000 g at 4 °C for 15 min. For immunoprecipitation, 4 μg of c-myc antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were added to the cleared cellular lysates, containing 1 mg of total protein, followed by incubation with rotation at 4 °C for 90 min. After 1 h incubation with 45 μl of the 25% protein G-agarose slurry (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), immunoprecipitates were washed four times with lysis buffer and analyzed for indicated proteins by immunoblotting as described previously (Chen et al., 2011). The mutated form of rictor displays a low binding to Sin1 in comparison with wild type. (c) Similar study has been performed and analyzed as in (a), where myc-rictor and its mutants have been co-expressed with the Flag-tagged Protor 1α. (d) The Leu-923 and Leu-943 sites of rictor are not crucial for the rictor/Sin1 interaction. The L923E and L943E myc-tagged rictor mutants were transiently expressed together with Sin1-V5 in 293T cells. To reach equal to the wild-type rictor level of expression, the same optimization as in (b) was performed. The cells were lysed and the assembled complexes were immunopurified as described in (b).

To address a role of this conserved Gly-934 residue in rictor, we performed the functional study by mutating this rictor site. We have introduced the G934E substitution mutation within the human rictor cDNA that mimicked the reported point mutation in its C. elegans ortholog. Rictor forms a heterodimer with its binding partner Sin1, and this heterodimer interacts with mTOR to assemble mTORC2 (Frias et al., 2006; Jacinto et al., 2006). The formation of the rictor/Sin1 heterodimer by the rictor G934E mutant was addressed by transient co-expression of the myc-tagged wild-type rictor or its mutant form with V5-tagged Sin1 (Figure 1b) because the endogenous mTORC2 components do not interfere with the interactions of the transiently expressed rictor and Sin1 (Chen and Sarbassov, 2011). When similar amounts of cDNAs (1X) were applied for transfection in 293T cells, we detected a very low level of the mutant rictor expression compared with the wild type, suggesting that the mutant form of rictor is a highly unstable protein. To optimize the rictor mutant expression to the expression level comparable to its wild-type form, the amount of mutant rictor cDNA was increased five times (5 ×). Because Sin1 protein stability depends on rictor expression (Frias et al., 2006; Jacinto et al., 2006), we adopted a similar optimization step by increasing the Sin1 cDNA amount for transfection. Following the optimization of rictor and Sin1 expression, we found that the wild-type rictor co-purified with a substantial amount of Sin1 and only a weak signal of Sin1 was detected with the immunopurified rictor mutant. Even a high level of the mutant expression (5 ×), as detected in cell lysates (Figure 1b, lower panel), did not show any substantial binding of the myc-rictor G934E mutant to Sin1. Our co-expression data indicate that a substitution of glycine residue at the position 934 to glutamic acid in the human rictor protein carries a significant effect by impeding binding of rictor to Sin1. This mutation controls particularly the Sin1 binding without affecting the binding of another rictor-interacting protein Protor (Pearce et al., 2007; Woo et al., 2007). We found that when comparable levels of rictor wild type or its mutant were co-expressed with Protor 1α, we detected a similar abundance of Protor 1α co-purified with the myc-tagged rictor or its mutant (Figure 1c). A similar rictor G934D mutation carrying the substitution of Gly-934 to a negatively charged aspartic acid also prevented binding of Sin1 (Figure 3a), but did not interfere with the binding of Protor 1α. The binding of Protor 1α to rictor was specific because the purified control myc-tagged protein gamma-tubulin complex protein 2 did not show the protein interaction. In our immunoblots the Protor 1α band was detected as a doublet, as it has been previously reported (Pearce et al., 2010, 2011). Our data indicate that the rictor Gly-934 site determines the binding of Sin1, whereas the binding of Protor 1α to rictor takes place independent of Sin1 on a distinct site of rictor.

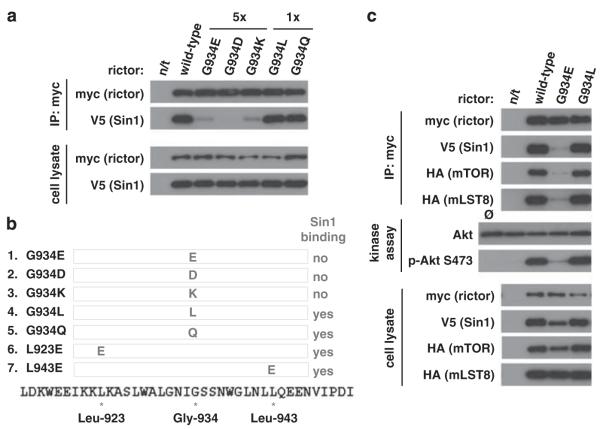

Figure 3.

The charged amino acids replacing Gly-934 residue of rictor prevent the rictor’s binding to Sin1. (a) The myc-tagged wild-type rictor and its G934E, G934D, G934K, G934L, G934Q mutants and Sin1-V5 cDNAs were transiently expressed in 293T cells. To equalize the level of expression for non-interacting mutants, the indicated increased amounts of DNA (5 ×) for both rictor and Sin1 were applied for transfection. After 48 h, the transfected cells were harvested and rictor/Sin1 complexes were immunoprecipitated as described in Figure 1b. Whenever non-polar Gly-934 is mutated to any charged amino acid, rictor/Sin1 interaction is impaired. Non-charged amino acids at this site have the wild-type phenotype. (b) The summary table indicating the property of the rictor mutants to interact with Sin1. In our study, we developed and analyzed seven mutants of rictor: G934E, G934D, G934K, G934L, G934Q, L923E and L943E. (c) To assemble mTORC2, 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg myc-rictor, 500 ng HA-mTOR, 400 ng Sin1-V5 and 100 ng HA-mLST8 cDNAs. For G934E mutant 5 μg rictor was used. Following cell lysis, mTOR complexes were immunoprecipitated and used for in vitro kinase assay with full-length GST-Akt as a substrate, as has been previously described (Sarbassov et al., 2005b). 15 μl of kinase buffer containing 500 ng inactive Akt1-GST and 500 μm ATP were added to the immunoprecipitates and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 200 μl ice-cold enzyme dilution buffer (20 mm 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid, pH 7.0, 1 mm EDTA, 0.3% CHAPS, 5% glycerol, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin). After a quick spin the supernatant was removed from the protein G-agarose and a 15 μl portion of the former was analyzed by immunoblotting for phospho-S473 Akt and total Akt levels. The pelleted protein G-agarose beads were also analyzed to determine the levels of rictor, Sin1 and mTOR in the immunoprecipitates. These data indicate that rictor G934L mutant is assembled into the functional mTOR complex 2 as determined by in vitro kinase assay.

The area surrounding the highly conserved Gly-934 site might be important for the rictor protein-folding and has a negative effect on the interaction between rictor and Sin1 interaction. To test this hypothesis, we altered the conserved bulky hydrophobic amino acids of rictor Leu-923 and Leu-943 flanking the rictor Gly-934 site to the negatively charged glutamic acid. Both rictor L923E and L943E mutants showed low level of expression following expression of their cDNAs in 293T cells, resembling the expression of the G934E mutant. We optimized the expression of the mutants by increasing the DNA amount fivefold to be applied for transfection. Interestingly, in contrast to the G934E mutant, both L923E and L943E rictor mutants formed a complex with Sin1 and we detected only a small decrease in formation of the heterodimer compared with the wild-type rictor (Figure 1d). The three rictor mutants that we studied showed a low expression level, which might be caused by altered protein folding leading to their low stability and short half-lives (Cordes et al., 1996). We found that the replacement of the non-polar Gly-934 residue with the negatively charged glutamic acid prevents binding of rictor to Sin1, whereas other similar substitutions of Leu-923 and Leu-943 did not alter the rictor and Sin1 interaction. Our data indicate that a single amino-acid residue, Gly-934, of rictor is critical to form a complex with Sin1, but not with Protor 1α.

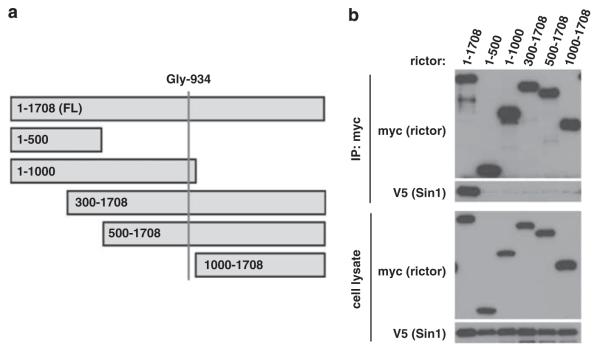

The Sin1-binding domain of rictor has not been identified. If rictor Gly-934 site determines the binding of rictor to Sin1, the rictor Sin1-binding domain might be located around this site. In an attempt to locate the Sin1-binding domain of rictor, we developed several rictor-truncated mutants missing the N- or C-terminal parts of the protein (Figure 2a). The co-expression of the myc-tagged wild-type full-length rictor or its truncated mutants with the V5-tagged Sin1 shows that only the full-length rictor interacts with Sin1 (Figure 2b). We found that none of the mutants containing the first conserved 1000 amino acids of rictor sequence or carrying deletion of its first 300 amino acids interacted with Sin1. This study shows that a full length of rictor is required to bind to Sin1, although the substitution of a single non-polar amino-acid glycine at the position 934 to the negatively charged glutamic acid within the rictor protein prevents its binding to Sin1.

Figure 2.

The full-length rictor is required for its association with Sin1. (a) In order to locate the rictor/Sin1 interaction domain, different truncated versions of wild-type rictor were created: 1–500, 1–1000, 300–1708, 500–1708 and 1000–1708. (b) Only full-length of rictor binds to Sin1. The myc-tagged rictor fragments were transiently co-expressed with the full length Sin1-V5 in 293T cells. After 48 h, the transfected cells were lysed and rictor/Sin1 complexes were immunoprecipitated as described in Figure 1b.

To address further how altering the Gly-934 site changes the binding of rictor to Sin1, we mutated this site to the charged, polar or non-polar (hydrophobic) amino acid. We found that a substitution of this site by the acidic aspartic acid or basic lysine residue resembled the rictor G934E mutant. Following their optimized expression, we did not detect the binding of Sin1 to the rictor mutants (Figure 3a), indicating that a substitution of the rictor Gly-934 site by the negatively or positively charged amino acid interferes with the binding of rictor to Sin1, whereas a substitution of the Gly-934 site by the non-polar leucine or polar non-charged glutamine does not interfere with the rictor expression, and both these mutants act as the wild-type rictor by forming a heterodimer complex with Sin1 (Figure 3a). These data indicate that replacement of the rictor Gly-934 residue by the negatively or positively charged, but not by the polar non-charged or non-polar amino acid, has a substantial impact on the rictor by preventing its binding to Sin1 (Figure 3b).

Assembly of mTORC2 requires formation of the rictor/Sin1 heterodimer because rictor or Sin1 does not bind to the mTOR/mLST8 complex alone (Frias et al., 2006). The co-expression of the four essential components of mTORC2 (HA-mTOR, HA-mLST8, myc-rictor and V5-Sin1) is sufficient to reconstitute the functional mTORC2 complex carrying the kinase activity towards its substrate Akt (Chen and Sarbassov, 2011). By applying a similar reconstitution system, we found that the wild-type rictor and its G934L mutant assembled into the functional mTORC2 kinase complex, as detected by phosphorylation of Akt on Ser-473 (Figure 3c). On the contrary, the rictor G934E mutant failed to form mTORC2 and the immunopurified rictor alone did not show kinase activity. This functional study indicates that, similar to the wild-type rictor, its G934L mutant, by forming a rictor/Sin1 heterodimer, assembles into mTORC2, whereas its G934E mutant fails to bind to Sin1 and does not get assembled into the kinase complex.

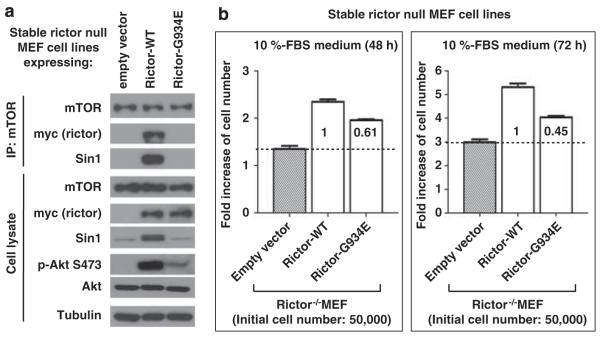

Rictor is the essential component of the mTORC2 kinase complex known to function as a regulatory Ser-473 kinase of Akt (Sarbassov et al., 2004, 2005b). Loss of rictor carries a profound inhibitory effect on regulation of Akt. Introduction of the stable rictor expression into the rictor null mouse embryonic fibroblasts has been shown to reconstitute the Akt signaling associated with the increased rate of cell proliferation (Chen et al., 2011). In our study, we characterized a role of the rictor G934E mutation in regulation of Akt and cell proliferation. To establish the stable expression of rictor in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, we applied the retrovirus expression system as described previously (Chen et al., 2011). To optimize the expression levels of the wild type and its G934E mutant, the titer of the virus carrying the wild-type rictor cDNA has been decreased four times. We found that stable expression of the wild-type rictor in the rictor null mouse embryonic fibroblasts stabilized the Sin1 expression and reconstituted the Akt signaling, as detected by phosphorylation of Akt on Ser-473 (Figure 4a, lower panel). Importantly, similar expression of the rictor G934E mutant failed to stabilize Sin1 expression and carried a low effect on the Akt Ser-473 phosphorylation. Sin1 protein stability depends on the binding of Sin1 to rictor (Frias et al., 2006) and we found that only expression of the wild-type rictor, but not its G934E mutant, stabilized the Sin1 expression. The rictor mutant is deficient in regulation of Akt, as detected by its phosphorylation on the mTORC2-dependent site (Figure 4a, lower panel), because of the lack of mTORC2 in the mutant cells, as indicated by the undetectable levels of rictor and Sin1 co-purified with mTOR (Figure 4a, upper panel). Moreover, we found that loss of the mTORC2 activity in cells expressing the rictor G934E mutant associates with the low rate of cell proliferation (Figure 4b). We found that the rictor null mouse embryonic fibroblasts carrying a stable expression of the rictor G934E mutant at the 48-h time-point show only 60% of the rictor-dependent cell proliferation rate compared with the cells expressing wild-type rictor. At the 72-h time point this difference is increased up to 45%. This finding indicates that the rictor G934E mutant is not compatible with the rictor wild type in promotion of cell proliferation, which correlates well with a lack of the mTORC2-dependent activation of Akt in the mutant cells. Thus, our data indicate that the rictor G934E mutant is not capable of binding to its partner Sin1 and does not assemble into the functional mTORC2 kinase complex, causing deficiency in Akt signaling and cell proliferation.

Figure 4.

The rictor G934E mutation leads to deficiency of the mTORC2 signaling and inhibition of cell proliferation. Stable expression of the wild-type rictor and its G934E mutant in the rictor-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) has been achieved by the retroviral expression system as described previously (Chen et al., 2011). Because of the low expression level of the mutant, we optimized its expression with the wild-type rictor by diluting the titer of the virus carrying the wild-type rictor cDNA four times. (a) The rictor-null MEFs expressing the wild type and its G934E mutant have been analyzed by immunoprecipitation of mTOR with the following immunoblots of the cell lysates (lower panel) and immunoprecipitates (upper panel) with the indicated antibodies. (b) Point mutation of rictor at Gly-934 inhibits cell proliferation. Cell proliferation of the rictor-null MEFs with a stable expression of the wild-type rictor or its G934E mutant shown in (a) was analyzed. As indicated, cell proliferation was assessed by plating 50 000 cells into six-well plates and cell counting was done after 48 and 72 h of incubation of cells in 10% serum. The cell number data were graphed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Results are reported as mean±s.d. of three independent experiments. Comparisons were performed with a two-tailed paired Student’s t test. In all tests, P<0.05 was considered significant.

In summary, our study explains how a single point mutation of rictor resembles the loss of rictor and the TORC2-deficient phenotype, initially identified in C. elegans as the rictor G1120E mutation in the recent genetic screening study (Jones et al., 2009). Our study shows that the analogous mutation in human rictor by a substitution of the highly conserved glycine to glutamic acid (G934E) interferes with the binding of rictor to Sin1. The substitution of Gly-934 with several other residues revealed that the introduction of the negatively (glutamic or aspartic acid) or positively (lysine) charged amino acid at this position interferes with the binding of rictor to Sin1, because the substitution of the non-charged leucine or glutamine resembles the wild-type rictor by forming the rictor/Sin1 heterodimer. Assembly of mTORC2 depends on the binding of rictor/Sin1 to mTOR/mLST8. Our functional studies reveal that the rictor G934E mutant is not capable of forming the rictor/Sin1 heterodimer and is deficient in mTORC2 signaling, as detected by impaired Akt signaling and cell proliferation. Our data indicate that the Gly-934 site on the human rictor protein controls the rictor/Sin1 interaction and assembly of mTORC2.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the MD Anderson Trust Fellow Fund and NIH grant CA133522 (DDS). R Aimbetov and O Bulgakova have been partially supported by the Ph.D. training grants from Kazakhstan. We are thankful to our laboratory member Dr Tattym Shaikenov for providing the Akt substrate. We are also thankful to Dr Dario Alessi (University of Dundee, Dundee, England) for providing the Protor 1α expression plasmid.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, et al. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayascas JR. Dissecting the role of the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) signalling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2978–2982. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Ahmed NN, Datta K, Malstrom S, Stokoe D, et al. Akt activation by growth factors is a multiple-step process: the role of the PH domain. Oncogene. 1998;17:313–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozulic L, Surucu B, Hynx D, Hemmings BA. PKBalpha/Akt1 acts downstream of DNA-PK in the DNA double-strand break response and promotes survival. Mol Cell. 2008;30:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-H, Sarbassov DD. The mTOR kinase activity determines functional activity and integrity of mTORC2. J Biol Chem (resubmitted) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Shaikenov T, Peterson TR, Aimbetov R, Bissenbaev AK, Lee SW, et al. ER stress inhibits mTORC2 and Akt signaling through GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation of rictor. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citri A, Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes MH, Davidson AR, Sauer RT. Sequence space, folding and protein design. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, et al. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JM, Yee D. The type-1 insulin-like growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase and breast cancer: biology and therapeutic relevance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:327–336. doi: 10.1023/a:1023720928680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. An expanding role for mTOR in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, et al. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell. 2006;127:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Greer ER, Pearce D, Ashrafi K. Rictor/TORC2 regulates Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage, body size, and development through sgk-1. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Huang X, Boudeau J, Pawlowski R, Wullschleger S, Deak M, et al. Identification of Protor as a novel rictor-binding component of mTOR complex-2. Biochem J. 2007;405:513–522. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Komander D, Alessi DR. The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Sommer EM, Sakamoto K, Wullschleger S, Alessi DR. Protor-1 is required for efficient mTORC2-mediated activation of SGK1 in the kidney. Biochem J. 2011;436:169–179. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005a;17:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005b;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J, Lemmon MA. SH2 and PTB domains in tyrosine kinase signaling. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE12. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.191.re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukas AA, Kane EA, Carr CE, Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Rictor/TORC2 regulates fat metabolism, feeding, growth, and life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2009;23:496–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.1775409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Painter GF, Holmes AB, et al. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science. 1998;279:710–714. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SY, Kim DH, Jun CB, Kim YM, Haar EV, Lee SI, et al. PRR5, a novel component of mTOR complex 2, regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25604–25612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yee D. Tyrosine kinase signalling in breast cancer: insulin-like growth factors and their receptors in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:170–175. doi: 10.1186/bcr50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]