Abstract

Objective. To implement and assess an elective course that engages pharmacy students’ interest in and directs them toward a career in academia.

Design. A blended-design elective that included online and face-to-face components was offered to first through third-year pharmacy students

Assessment. Students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward academic pharmacy were measured by pre- and post-course assessments, online quizzes, personal journal entries, course assignments, and exit interviews. The elective course promoting academic pharmacy as a profession was successful and provided students with an awareness about another career avenue to consider upon graduation. The students demonstrated mastery of the course content.

Conclusions. Students agreed that the elective course on pharmacy teaching and learning was valuable and that they would recommend it to their peers. Forty percent responded that after completing the course, they were considering academic pharmacy as a career.

Keywords: academic pharmacy, teaching, student awareness, faculty, career

INTRODUCTION

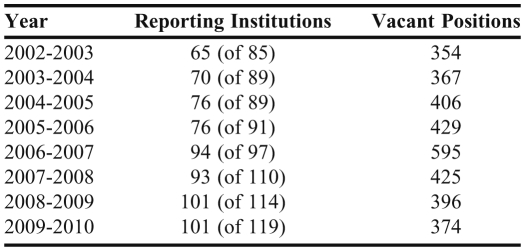

The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) has indicated a need for and shortage of pharmacy academicians.1 There were 354 vacant or lost faculty positions in colleges and schools of pharmacy in 2002 and 374 in 2010 (Table 1). AACP trend data for this 8-year period highlights an increasing growth rate and interest in the pharmacy profession, with 5,329 more students graduating with PharmD degrees in 2010 than in 2002.3 The increase in the number of pharmacy teaching institutions likely contributed not only to this trend but also to the shortages in academic pharmacy faculty members. Furthermore, it may be these factors that draw attention to the faculty shortage, especially as faculty members continue to be in demand as academic institutions expand. The faculty shortage may also be attributable to the inability of institutions to recruit graduating students to academia compared with that to other pharmacy career. Qualified health professionals were often enticed into industry positions with lucrative salaries and not enough were entering the professoriate.4 Academic institutions usually cannot compete with industry benefits.2,6-10

Table 1.

Vacant Budgeted and Lost Faculty Positions Brief Data2

Another potential reason for the academic pharmacy faculty shortage may be related to student misconceptions or lack of knowledge about the academic profession as a career.11 The professorate is comprised of 3 distinctive roles: teaching, service, and scholarship.12 Teaching is largely understood by students to be what they see in the classroom, whereas service and scholarship involve activities such as clinical faculty site responsibilities, advising, research initiatives, residency trainings, educational research, committee work, and conference attendance. Most students are unaware of their professors’ responsibilities prior to and after lectures and beyond the classroom.13 This lack of understanding, coupled with students’ general lack of confidence or distain for public speaking, may negatively impact the likelihood that they would seriously consider academic pharmacy as a career. Continued faculty shortages will create a serious problem for the future of pharmacy with respect to the ability of programs to handle their student enrollments as well as faculty workload, and quality of life. This trend also has the potential to jeopardize the quality of education pharmacy colleges and schools can offer students.

To educate pharmacy students about the professoriate and interest them in an academic career, an elective course in teaching and learning was created at Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (ACPHS). The objective of the course was to engage students in the study of education and to promote academic pharmacy as a career. Teaching, service, and scholarship responsibilities were all covered within the course with an emphasis on pedagogy. Course objectives reflected the measurable outcomes expected from this focus. Students were given a healthy glimpse of service and scholarship responsibilities in academia; however, this course was designed as an introductory and possible prerequisite for future courses or electives that could emphasize specific pedagogical topics or expand on service and scholarship roles, such as educational research, the scholarship of teaching and learning, learning assessment, site/clinical responsibilities, or residency and fellowship training. Although preceded by significant efforts in the field to engage students toward an academic pharmacy career, this elective course is an innovative approach to formally educating pharmacy students about the professorate prior to graduation and residency program.14

DESIGN

Teaching and Learning in Higher Education is a 15-week, 3-credit elective course. It was first offered in 2009 to ACPHS students in doctor of pharmacy curriculum years 1 through 3, which include students in their third, fourth, and fifth years at the college. This group was selected because they had developed more knowledge, skills, and maturity compared with first- and second-year prepharmacy students.

Co-taught by 4 instructors, the course included various pedagogical topics such as educational theory, student motivation, lesson and outcome-based planning, teaching strategies, assessment, instructional technology and design, adult learning, and characteristics of the professorate. The combination of instructor qualifications was important to the success of this elective. The course coordinator had a doctor of philosophy (PhD) degree in curriculum and instruction. The 3 co-instructors had doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degrees, and each was engaged in 1 of 3 aspects of the education process: assessment, teaching methodology, and lesson planning. The required textbook for the course was H. Fry's Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice.15 Educational research was used as supplemental course content because these data usually promote the advancement of teaching and expose students to its value. Educational research selections with a pharmacy teaching focus were used to immerse students in the realities and environment of this discipline. In addition to traditional study, students analyzed and were introduced to the teaching process through teaching moments, wherein they prepared and taught a lesson to fellow students and course faculty members. They also evaluated the teaching process by shadowing a professor of their choice. Journal reflective writing assignments were built into the course to promote metacognition, defined as thinking about thinking or knowing about knowing.16 This self-regulatory cognitive process was important to include as a formal assignment because these students were learning about a discipline beyond the regular scope of pharmacy topics.

Course objectives, which were created to promote higher-order learning, included the following: describe and recall the major educational theories and their application in the design and delivery of instruction; develop, implement, and evaluate teaching in higher education, particularly a pharmacy-related classroom, consultation, preceptor, or clinical interaction; apply best-practice assessment measures within a lesson plan to evaluate knowledge, understanding, and student learning; identify and incorporate instructional technology events in and outside the classroom; and teach a lesson on a chosen topic in front of instructors, experts, and peers that incorporated educational theories and best practices.

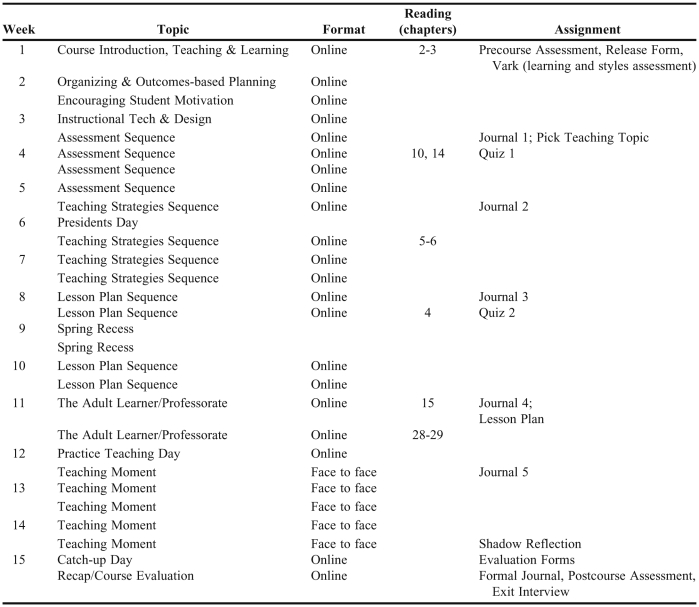

The course format was developed around best practices from hybrid/blended-learning curriculum design.17 Ninety percent of the course was completed online and 10% was accomplished face-to-face. The online components included weekly coursework and content, discussion-board activities, online assessments, and journaling assignments. The face-to-face component was reserved for the presentation of the teaching moments to peers and course faculty members. Table 2 highlights a sample course schedule displaying timeline, topic(s), format, reading, and assignments. Considerable time and effort were invested in developing a user-friendly online environment. The navigation menu highlighted the importance of the course map, an electronic organizer for students, which charted out the course on a week-by-week basis, leading students to understand expectation and flow. Each week, there were consistently displayed learning objectives, content introduction, course material, activities/assignments, and assessment.

Table 2.

Schedule for the Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Course

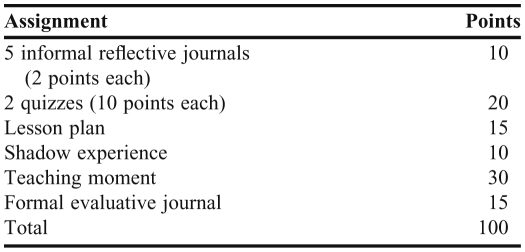

Questioning and feedback were a major part of the course design, and discussion boards were used heavily to enable an environment of thoughtful exchange. Students were assigned to groups to help foster communication. Additionally, course faculty members commented individually to each student on all of their journals and shadowing assignments. Weekly content was designed to build on previously learned material to help students scaffold the development of their teaching moments. Each week, students were given feedback on their teaching moments as they were developed. This occurred with faculty members in the discussion board and through comments in their journal assignments. Teaching moments were developed slowly over the first half of the course, culminating with complete lesson plans that were evaluated by course faculty members. Students then used their lesson plans to design their teaching moments. Faculty and peer questions, critical discussions following each teaching moment, and students’ formal self-evaluations of their teaching moments helped to foster understanding and success. Course grades were included to give a framework for recognizing the student experience and to consider course content choices. Grades were comprised of summative assessments from students’ major assignments, each of which was evaluated by a rubric. Faculty members provided continuous feedback to students on their progress as the semester progressed. Table 3 describes the allocation of points.

Table 3.

Grading for the Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Course

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Teaching and Learning in Higher Education was offered during the spring semester of 2009, 2010, and 2011. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from 26 students with a 100% response rate; 2009 (3), 2010 (13), and 2011 (10). Pre- and post-course assessments, online quizzes, discussion-board and journal conversations, teaching and shadowing assignment reflections, and exit interview data were collected and analyzed.

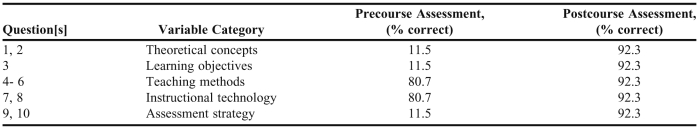

Assessment data were collected on student knowledge and understanding before and after the course offering. Short-answer assessment questions inquired about theoretical concepts, learning objectives, teaching methodologies, instructional technology, and assessment strategies. The 10-question precourse assessment results revealed that students had only a basic understanding of pedagogy prior to taking the elective (Table 4). The majority of students (21/26) scored well on questions dealing with technology and teaching methods but much lower on questions about theoretical concepts, learning objectives, and assessment. Postcourse assessment data demonstrated that students’ content knowledge increased across all question categories, with 24 out of 26 students answering all questions correctly. Students also scored well on course quizzes. Two summative quizzes were administered during the semester to measure 8 weeks of vocabulary, knowledge, and understanding.

Table 4.

Pre- and Post-course Assessment Results

Students spent much time and effort responding to assignments, questions, and their peers in the discussion board each week. Discussion-board dialogues displayed students’ ability to apply, synthesize, and evaluate teaching and learning topics and provided evidence of student engagement with the topics they were learning about. Three distinct threads from the discussion board (ie, lesson planning, the professorate, and creating learning objectives) demonstrated authentic learning among students and provided a clear view of their engagement with the material and with each other. These qualitative data showed how students reasoned through the content, as they processed new information. The data also provided evidence of how students were creating relationships between new and pre-existing knowledge, as they discussed their perspective and responded to peers. Specifically, students recognized lesson planning as the key to course development and pointed to well-written, measurable objectives as key tools in this process. The importance of these tools was implicitly stated when students likened it to a foundation on a house.

Students did not realize the complexities of academia nor the promotion and tenure process. The course opened their eyes to this aspect of pharmacy education, as illustrated by conversations that ranged from faculty time commitments, service, and clinical responsibilities. Educational and scientific research was found to be a foreign concept to most students. They assumed that when faculty members were not teaching, they were either home or otherwise enjoying personal time. Conversations after completion of the course clearly demonstrated a change in student opinions from thinking that teaching is an easy profession to having respect for the multiple responsibilities of academic pharmacists.

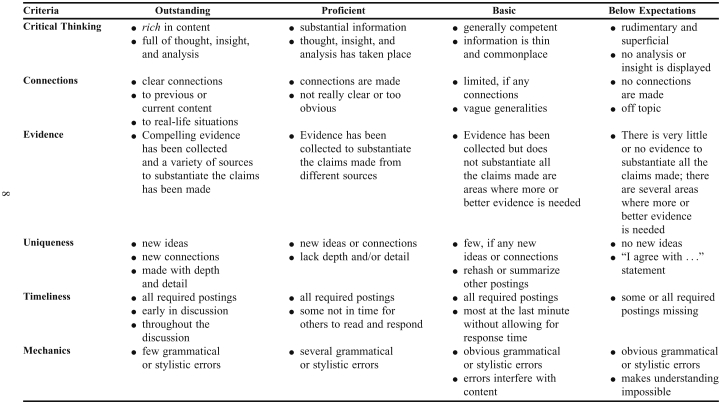

All students (N = 26) actively participated in the discussion-board assignments and peer collaboration. Although discussion-board conversations were not graded, a rubric was used as a model for students so they could understand the different types of dialogues that can occur (Appendix 1). Sixty-five percent of discussion-board conversations were categorized as outstanding or proficient, while 23% were basic, and the remaining 12% were below expectations.

Along with discussion boards, students self-regulated their learning in their journal entries. With each entry they were prompted to answer the following questions: (1) what did you learn? (2) How do you know you learned it? (3) What did you leave class thinking about? (4) What helped your learning? (5) What hindered your learning? (6) What do you need to learn better? (7) What else? Is there anything else you want to say? (8) You may also wish to use this assignment as a way to communicate with the instructor (eg, ask questions? Do you need further explanation on something? Or help with your lesson plan development?

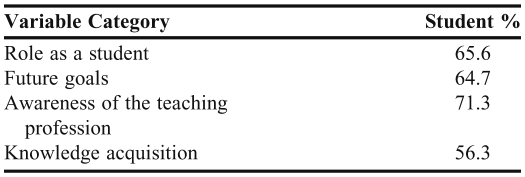

Some students found that the course helped them understand themselves as learners and engaged them further in the art of reflection. Journal entries were gathered to reveal students’ newfound appreciation and awareness of the teaching and learning process. These self-reflections were coded by the following categories: role as a student, future goals, awareness of the teaching profession, and knowledge acquisition (Table 5).

Table 5.

Student Journal Reflections Coded by Category

Metacognition worked well in this course, as assignments and course design promoted this kind of thinking and learning throughout the semester. Students gained a reflective perspective and applied this practice to their own learning and the content. Students did well on teaching moments, which accounted for 30 points of their course grade. Across the 3 years, only 1 student received a score below 25 points (mostly due to attendance issues). Students chose their own topics but had to narrow their objectives because of limited presentation time, a realistic constraint teachers have to deal with regularly. All students successfully demonstrated their skill and mastery of course content through this assignment.

Students also shadowed an actual class and interviewed the professor. Data from all 3 years yielded high grades for this assignment, with 25 of 26 students receiving 9 out of 10 points or better. Students designated this activity as their second favorite, with the teaching moment being the class favorite. Students used ideas and concepts from class to analyze curriculum, teaching methods, and student engagement. Analyzed class components included lesson objectives, teaching strategies and techniques, formative or summative assessment, student engagement, and technology. Students also had the option of accessing handouts and resources for the day of observation or obtaining permission to see the course materials on Blackboard page. Students spent one-to-one time with the professor and questioned him or her about various class components. During this interview, which followed the observation, students asked instructors to reveal their reasoning for why or how a particular course component (eg, lesson-plan usage, decisions on what to teach, teaching techniques, course-objective language and skill level, or assessment design) came to be.

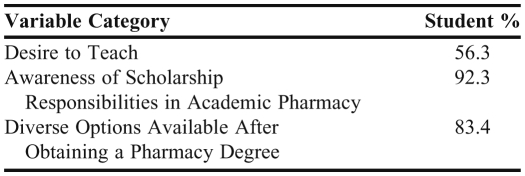

Entries in student journals focused on the profession of pharmacy and described students’ thoughts on academic pharmacy. Table 6 shows the collected reflections recoded for academic profession ideas, including desire to teach, awareness of scholarship responsibilities, and diverse career options available after obtaining a pharmacy degree.

Table 6.

Student Journal Reflections, Recoded

The general mindset of EDU301 students showed a clear shift toward the possibility of academia as a future career. Students frequently talked about their awareness of faculty scholarship roles and how excited they were to learn about another career option upon graduation. Furthermore, 56.3% reflected on their desire to teach. Two groupings emerged in the desire-to-teach category: students who had always had a passion to teach and those who did not know it was an option.

Students participated in exit interviews either face-to-face with an instructor or online at the end of the course. Across all 3 years, 10 questions were consistently asked. Of these, 4 questions and the corresponding responses emerged as valuable: (1) Are you more interested in pursuing a position in academia after completing this course? (2) Do you feel prepared to describe and recall educational theory and practice knowledge learned in this course? (3) Do you feel confident in teaching in front of instructors, experts, and peers by incorporating best practices? (4) Do you feel you can develop, implement, and evaluate teaching in higher education, particularly in a pharmacy-related classroom?

Students responded favorably to all 4 questions and expressed a clear understanding of the complexities of pedagogy. They all felt prepared to describe and recall educational theory and practice knowledge. They also grew more confident about presenting in front of experts and peers, a necessary skill in any professional environment. Student comments characterized a spectrum of feelings about pursuing an academic position, ranging from disinterest or fear to interest and attraction. One student reported considering academia as a second career after pharmacy practice. The majority of students stated that EDU301 prepared them to better evaluate teaching and classroom practices.

Although responses to these 4 questions varied, all student responses illustrated a deeper understanding of the teaching and learning process. All 26 students recognized academic pharmacy as a valid career choice available to them following graduation, as supported by data from student journals (Table 6). Moreover, 22 of the 26 students expressed interest in pursuing more courses or programs about the academic profession.

DISCUSSION

At the beginning of each semester, students felt they had a good understanding of the educational process. When asked, they pointed to their experience as a learner within the K-16 structure, which aided their understanding.18 However, much of what is seen and experienced as a learner does not justly reveal the professorate. As the course progressed, students realized they had limited knowledge about the educational system and teaching as a profession. Throughout the course, students were engaged with many teaching and learning topics. They interacted with and exposed the complexities surrounding the professorate, including service and scholarship. Remarkably, students made a valuable connection between pharmacy and academia. This new knowledge and connection may represent future promise for a career in education, with 84.6% of students expressing an interest in learning more about pharmacy academia.

Fostering lifelong learning and understanding was part of the course. Assignments and activities about learning styles, discussion board, journals, reflections, self-paced format, and active-learning projects engaged students in metacognition. After having learned about their own learning, thought about their own thinking, and taught about teaching as part of this course, students commented that they better understood themselves as learners and gained a new perspective on the education process. For example, the career-exploration activity offered students an opportunity to spend time with a college class and professor outside of the course. Job shadowing offered students a sense of the profession, as they were able to see pedagogy in action. In addition, the interview process gave students a deeper understanding of the class, content, and teacher as they began to analyze and learn about the education process.

Student feedback about how the course should change showed the maturity they gained in their academic knowledge. Students provided valuable examples and specific curriculum and design suggestions for improvement, exceeding what might be obtained from a course evaluation Likert scale or set of comments. Suggested changes included adding stronger tracking and management of students’ participation in the discussion board; reworking formative quiz questions to match learned content; adding a face-to-face day at the beginning of the course to help orient students to topics and environment; creating suggested due dates for discussion-board postings; tracking participation for accountability; and increasing student enrollment/interest in the elective so more students are exposed to the teaching path as a career option. Some students (6 of 26) reported that the content was sufficient but time consuming; however, they liked the subject matter and felt it was not too difficult to digest. Students also mentioned that assignment due dates were flexible, which made the course manageable, and that the consistent look and feel of the online course was well-designed. Finally, students noted that they liked professors’ feedback and presence both in the online and face-to-face formats, considered it advantageous to have multiple instructors, and appreciated the breadth and depth of the feedback provided.

A future study that uses EDU301 graduates as course and instructor evaluators would be valuable. Pharmacy colleges and schools could create an EDU301 student panel of evaluators to provide constructive feedback to instructors regarding course feedback. The study could collect and compare the quality and utility of such evaluators from previous methods. Based on sound educational theory and practice concepts, their input could aid in the improvement of this process.

This work could easily be translated to other institutions through the implementation of a similar elective. The course design and concepts are fully illustrated herein and would add much value to any pharmacy curriculum as a means of introducing students to the academic pharmacy profession. Finding the best combination of experienced instructors representing expertise and experience in pharmacy practice and in curriculum and instruction would be a key component of course success. There is limited research that looks at pharmacy student exposure to the teaching profession prior to graduation. Additionally, use of a teaching and learning elective as a method to promote academic pharmacy is still a new concept, with only 1 other instance in pharmacy education found.14 Thus, the current research is valuable, as it provides significant insight into opportunities that may help reduce the academic pharmacy shortage as well as empower students to realize a career they otherwise may not have considered. Students who decide early on in their education on a career in academic pharmacy and complete a residency program after graduation would be more adequately equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to teach successfully.

Next steps should include increasing EDU301 enrollment and awareness among the student body, creating more educational course electives, tracking EDU graduates and their chosen profession, and comparing first-year students with third-year students to identify similarities or differences in their attitudes toward and knowledge about academia.

SUMMARY

Offering an elective on teaching and learning in higher education is an excellent opportunity for pharmacy students to learn about and engage in the academic pharmacy profession. The blended and active-learning environment allowed students to work at their own pace and promoted critical thinking, lifelong learning, and communication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Gina Garrison, PharmD, and Michael Brodeur, PharmD, our colleagues who were involved with co-teaching of the course and who made valuable suggestions for this publication.

Appendix 1. Discussion-Board Rubric for the Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Course

REFERENCES

- 1.Academic Pharmacy. The Gateway to the Profession. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Alexandria, VA. http://www.aacp.org/resources/student/pharmacyforyou/pharmacycareerinfo/Documents/careeroverview.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2012.

- 2.Institutional Research Brief. Vacant Budgeted and Lost Faculty Positions, Academic Years 2002-2010. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Alexandria, VA. Volume 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Pages/InstitutionalResearchBriefs.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2012.

- 3.Trend Data. PharmD Degrees Conferred 1990-2010. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Alexandria, VA. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Pages/TrendData.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2012.

- 4.Bickel J, Brown A. Generation X: implications for faculty recruitment and development in academic health centers. Acad Med. 2005;80(3):205–210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCuskey R, Carmichael S, Kirch D. The importance of anatomy in health professions education and the shortage of qualified educators. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):349–351. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latif D. Attracting and retaining faculty at new schools of pharmacy in the Unites States. Pharm Educ. 2005;5(2):79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.PostScript. A good return: alumni give back by educating the next generation of pharmacists. Albany College of Pharmacy Magazine. 2008;19(1):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagraves R. Council of Deans Chairman's Section. A workforce issue: faculty needs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65(1):92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gourley D, LaMarcus W, Yates C, Gourley G, Miller D. Status of PharmD/PhD programs in colleges of pharmacy: the university of Tennessee Dual PharmD/PhD program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(2):Article 44. doi: 10.5688/aj700244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conklin M, Desselle S. Job Turnover intentions among pharmacy faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(4):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/aj710462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graduating Student Survey Information and Summary Reports. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. 2010. Alexandria, VA. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/institutionalresearch/Pages/GraduatingStudentSurvey.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2012.

- 12.O'Meara K, Rice RE. Faculty Priorities Reconsidered. Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox B, Siedow M. Do students understand the teacher? Clearing House. 1980;54(3):101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigelsky J. Exposing doctor of pharmacy students to an academic career through a teaching elective. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):Article 72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry H. A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice. (paperback) Routledge Falmer, 2009;3rd edition. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Flavell J. Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In: Resnick L, editor. The Nature of Intelligence. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hybrid Courses: References. Learning Technology Center. University of Wisconsin. Milwaukee, WI 2011. http://www4.uwm.edu/ltc/hybrid/references/index.cfm. Accessed January 12, 2012.

- 18.Van de Water G, Krueger C. P-16 Education. ERIC Digest, Clearinghouse on Educational Policy and Management, University of Oregon, 2002;159. [Google Scholar]