Abstract

Objective

Standard treatment for severe granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, previously Wegener’s granulomatosis) is daily oral cyclophosphamide (CYC), a cytotoxic agent associated with ovarian failure. In this study we assessed the rate of diminished ovarian reserve in women with GPA who received CYC versus methotrexate (MTX).

Methods

Patients in the Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial received either daily CYC or weekly MTX and were randomized to etanercept or placebo. For all women under 50, plasma samples taken at baseline or early in the study were evaluated against samples taken later in the study to compare levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), endocrine markers of remaining egg supply. Diminished ovarian reserve was defined as AMH<1.0ng/ml.

Results

Of 42 women in this analysis (mean age 35), 24 had CYC exposure prior to enrollment and 28 received the drug during the study. At study entry, women with prior CYC exposure had significantly lower AMH, higher FSH, and a higher rate of early menstruation cessation. For women with normal baseline ovarian function, 6/8 who received CYC during the trial developed diminished ovarian reserve, compared to 0/4 who did not receive CYC (p<0.05). Changes in AMH correlated inversely with cumulative CYC dose (p=0.01), with a 0.74ng/ml decline in AMH for each 10g of CYC.

Conclusion

Daily oral CYC, even when administered for less than 6 months, causes diminished ovarian reserve, as indicated by low AMH levels. These data highlight the need for alternative treatments for GPA in women of childbearing age.

Keywords: Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, fertility, cyclophosphamide, anti-Müllerian hormone, ovarian function

Introduction

Among women treated with cyclophosphamide (CYC), ovarian failure has long been viewed as an unfortunate but inevitable consequence of therapy. However, with recent successes in ovarian preservation and new alternative therapies for vasculitis, patients with this condition may now be able to avoid this treatment complication. Although the frequency of ovarian failure following CYC therapy in patients with vasculitis has not been previously assessed, reports have suggested that 30–50% of women receiving intravenous monthly CYC for other indications develop ovarian failure.(1–2) We suspected that the rate of ovarian dysfunction might be higher for women receiving daily oral CYC, the standard treatment protocol for vasculitis, as this method of administration exposes the ovary to toxic therapy daily and leads to cumulative doses 2–3-fold higher than those resulting from the monthly intravenous doses typically administered for other conditions.

In prior studies, ovarian failure has been determined according to two criteria: the cessation of menstruation and elevated levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). While these measures accurately identify women in menopause, they are less useful for assessing whether a woman has compromised fertility. Even in healthy women, fertility significantly declines in the two decades prior to menopause, when menstruation is still active and FSH levels are in the normal range.(3) Using only the presence of menses and high FSH levels to evaluate ovarian function thus underestimates the number of women with ovarian damage that can limit fertility and hasten menopause.

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is a newer marker that better reflects ovarian reserve and can predict the time to menopause. Produced by small early follicles whose ongoing growth is independent of the menstrual cycle, AMH by extension reflects the number of primordial follicles that remain in the ovary.(4) AMH provides several notable advantages over more traditional measures of ovarian function:

Exhibiting little fluctuation between or within menstrual cycles, AMH can be measured at any time in the cycle.(5).

In healthy patients, AMH levels decline slowly with aging, but among women who sustain ovarian injury from chemotherapy or radiation, these levels decline more rapidly.(6)

On average, a 40-year-old woman will have an AMH of 1.0ng/ml.(7) As AMH levels decline below this, conception becomes less likely (but not impossible).

The decline in AMH precedes the rise in FSH and menopause by several years.(8)

This is the first study of AMH in women with vasculitis. By comparing female vasculitis patients who have undergone CYC therapy with those who have not, we have been able to investigate the impact of this therapy on AMH and thus to assess associated subclinical ovarian damage and diminished ovarian reserve.

Patients and Methods

The Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of etanercept, a TNF-α inhibitor, for the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, previously Wegener’s granulomatosis). The study design and main results have been described in detail in earlier publications.(9)

In addition to receiving twice-weekly subcutaneous injections of etanercept, in 25mg doses, or placebo, all patients also underwent standard therapy for active GPA. Patients with severe disease received prednisone and daily oral CYC at a dose of 2mg/kg/day, with adjustments for renal insufficiency. Patients who presented with limited disease received prednisone and MTX in increasing weekly oral doses of up to 25mg. Patients with renal dysfunction received azathioprine instead of MTX. For patients who experienced severe GPA flares during the trial, therapy with CYC and glucocorticoids was initiated. Women were also allowed to take oral contraceptives, depot medroxyprogesterone, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists.

For this subanalysis of the WGET dataset, we included all women who were under 50 at the time of enrollment. Two time points for analysis were included for each qualified patient: the first available plasma sample (taken either at screening or at an early follow-up visit) and the last available plasma sample. After collection, the plasma samples were delivered to the University of North Carolina Immunotechnologies Core for ELISA, where AMH and FSH were measured.

Diminished ovarian reserve was defined as an AMH of <1.0ng/ml. For purposes of baseline analysis, patients were divided by age: under 18, when AMH tends to be on the increase; 18–35, during which years AMH tends to decline slowly; and over 35, when AMH is expected to approach 1.0ng/ml.

FSH is most reliable as a predictor of ovarian function when blood samples are drawn early in the menstrual cycle. In this study, however, blood draws were not timed with menses, which diminished the usefulness of FSH in assessing ovarian sufficiency. In addition, oral contraceptives and GnRH agonists suppress FSH, so all women on these medications were excluded from the FSH analysis. Menstrual history was only obtained at study entry.

Statistics

We assessed four primary outcomes. First, we compared the proportion of women with diminished ovarian reserve at study entry and completion based on prior CYC exposure. To evaluate the effect of CYC on AMH during the trial, we included only women with a baseline AMH >1.0ng/ml. To determine the dose effect of CYC on AMH, we employed regression analysis, with a p-value of <0.05 being considered statistically significant. Finally, women were divided by age to assess the role that age at CYC therapy has on ovarian function.

Results

Of the 180 total patients enrolled in the study, 42 were women under 50 at trial entry. Two of these women were excluded from the analysis of baseline hormone levels, as no sample had been taken for them prior to the administration of CYC during the trial. Thus, 40 women qualified for the baseline analysis, with a mean age of 35.2 years (±9.2 years; range 14–46). The majority were Caucasian (86%), educated beyond high school (64%), and either employed or in school (64%).

The patients’ baseline AMH concentrations were highly dependent on both age and prior CYC therapy (see table 1). Of 40 patients, 24 (60%) had received CYC prior to the first available hormone sample. For women between the ages 18 and 35, the mean AMH concentration was 4-fold higher and the rate of diminished ovarian reserve significantly lower among women who had not received prior CYC (p<0.01). For women over 35, a trend toward diminished AMH among those with prior CYC therapy was evident, but not statistically significant. Premature cessation of menstruation occurred predominantly in women over 35 with prior CYC exposure. FSH was almost 4-fold higher for women with prior CYC exposure, but the differences were not statistically significant based on age.

Table 1.

Menstruation and hormone levels at the first available sample.

| Women under age 50 |

No CYC prior to WGET enrollment |

CYC prior to WGET enrollment |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AMH at first sample: ng/ml (SD) | ||||||

| All patients | 1.4 (2.0) | 2.5 (2.4) | n=16 | 0.6 (1.2) | n=24 | 0.002 |

| Under 18 years old | 1.6 (1.8) | 0.67 | n=1 | 2.0 (2.3) | n=2 | NA2 |

| 18–35 years old | 2.5 (2.4) | 4.2 (1.9) | n=7 | 1.0 (1.7) | n=8 | 0.004 |

| 35 years and over | 0.6 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.9) | n=8 | 0.3 (0.4) | n=14 | 0.14 |

| Diminished Ovarian Reserve (AMH<1.0ng/ml) | ||||||

| All patients | 70% | 50% | n=16 | 83% | n=24 | 0.03 |

| Under 18 years old | 67% | 100% | n=1 | 50% | n=2 | NA2 |

| 18–35 years old | 40% | 0% | n=7 | 75% | n=8 | 0.003 |

| 35 years and over | 91% | 86% | n=8 | 93% | n=14 | 0.6 |

| Premature cessation of menstruation: N (%) | ||||||

| All patients | 21% | 0% | n=16 | 33% | n=24 | 0.013 |

| Under 18 years old | 0% | 0% | n=1 | 0% | n=2 | NA2 |

| 18–35 years old | 6% | 0% | n=7 | 13% | n=8 | 0.32 |

| 35 years and over | 36% | 0% | n=8 | 50% | n=14 | 0.015 |

| Baseline FSH by age group1mIU/ml (SD) | ||||||

| All patients | 14.9 (20.9) | 5.3 (7.6) | n=12 | 20.63 (24.2) | n=20 | 0.042 |

| Under 18 years old | 4.4 | 4.4 | n=1 | -- | NA2 | |

| 18–35 years old | 8.2 (11.1) | 2.2 (2.0) | n=4 | 11.67 (12.9) | n=7 | 0.19 |

| 35 years and over | 19.1 (24.4) | 7.2 (9.7) | n=7 | 25.45 (27.8) | n=13 | 0.11 |

FSH analysis does not include women currently taking oral contraceptives or GnRH-agonists.

Too few subjects for reliable statistical testing.

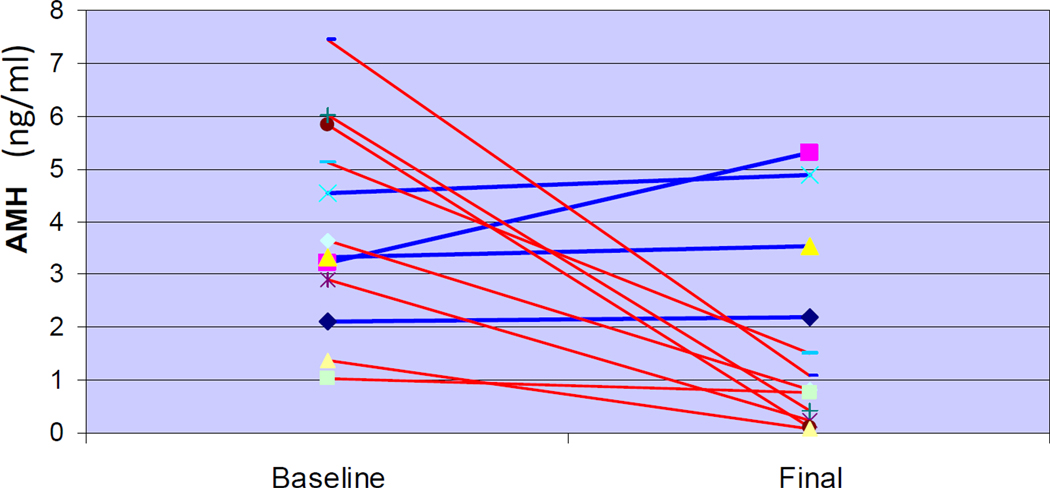

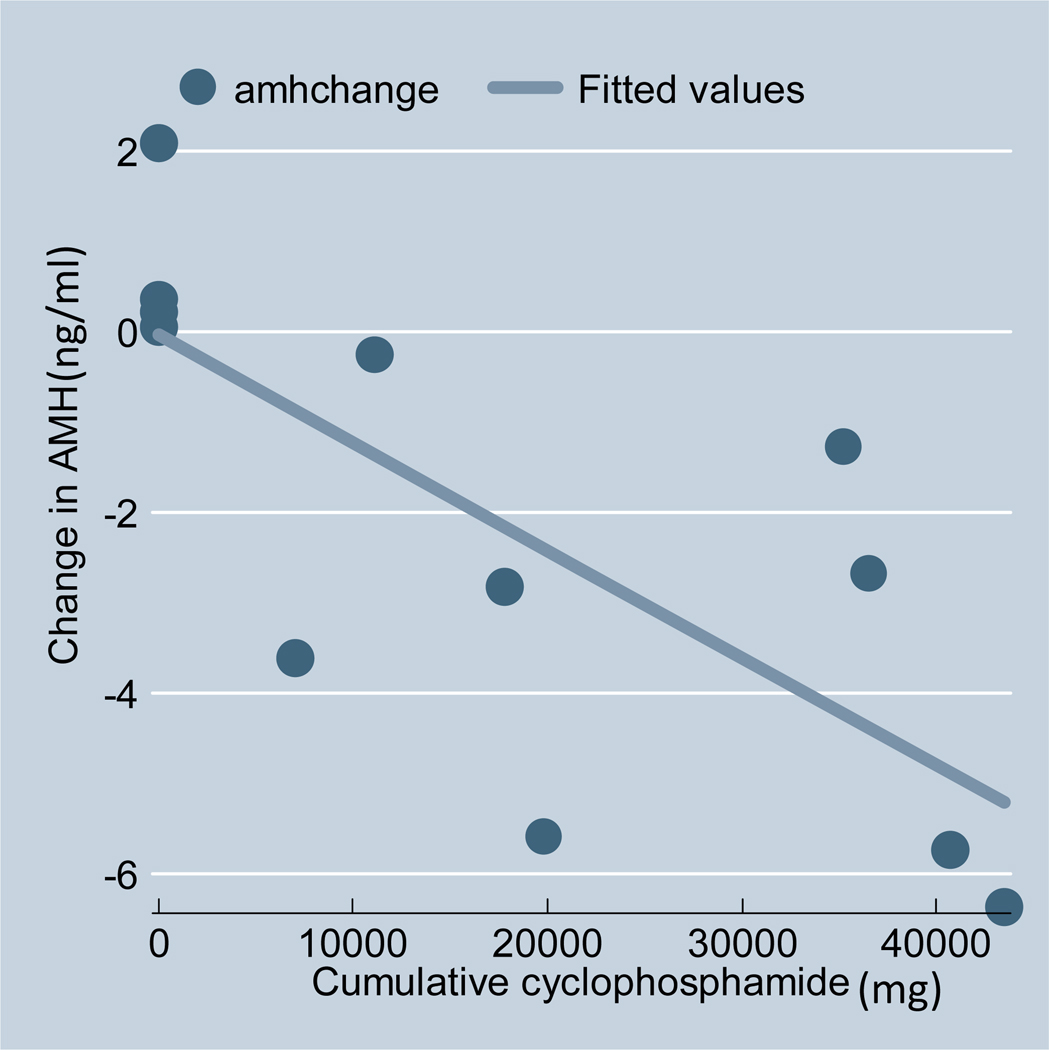

Only 12 women entered the study with normal ovarian reserve. In this group, those treated with CYC during WGET experienced a decline in AMH levels significantly greater than that experienced by women who did not receive CYC (see figure 1). The 8 women who received CYC had a mean decline in AMH from 4.2ng/ml (± 2.3ng/ml) to 0.6ng/ml (± 0.5ng/ml). The 4 women who did not receive CYC registered a modest increase in their mean AMH concentrations, from 3.3ng/ml (± 1.0ng/ml) to 4.0ng/ml (±1.4ng/ml) (p=0.005, comparing the change in CYC exposed vs non-CYC exposed women). Of these 4 women, 3 were adults whose AMH levels remained steady; one young patient’s AMH levels rose as she went through puberty. The degree of change in AMH was predicted by the cumulative dose of CYC administered during the trial (regression coefficient −0.074, p<0.01). For each 10g of CYC administered, the AMH level fell, on average, 0.74ng/ml (see figure 2). Adjusting for age at study entry did not impact the statistical significance of the correlation between cumulative CYC dose and decline in AMH. The AMH of 2 women increased modestly (0.59 and 0.83 ng/ml) 3 years after CYC cessation. This study was not powered to identify other risk factors for AMH decline.

Figure 1.

Change in AMH during WGET for women with baseline AMH>1.0ng/ml. Red: received CYC during WGET. Blue: did not receive CYC during WGET.

Figure 2.

The change in AMH(ng/ml) by cumulative CYC dose (mg) during WGET. This analysis included only women with a baseline AMH of >1.0ng/ml.

Every dosage level of CYC appeared to significantly decrease AMH in this study. Even the 3 women under 35 who received <12.5g of CYC prior to study entry had a baseline AMH lower than expected for their age (range 0.47 to 1.03 for women aged 23–32). Of 10 women under 35 who received 12.5g–25g of CYC, only 2 exited the study with AMH levels over 1.0ng/ml. These data suggest that most, but not all, women treated with a short course of daily oral CYC sustain significant ovarian damage.

Discussion

This study documents the rapid ovarian damage caused by oral CYC in women under 50 who undergo treatment for granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, previously Wegener’s granulomatosis). At baseline, women with prior CYC therapy had a significantly lower AMH, higher FSH, higher rate of diminished ovarian reserve, and were more likely to have premature cessation of menses. Regardless of their baseline measures, all women under 50 treated with CYC during the trial suffered in a dramatic decrease in AMH. The cumulative dose of CYC was directly correlated to the degree of this decline, but even a low cumulative dose over a short duration was associated with unusually low AMH.

Although previous studies of women with rheumatologic disease have likewise documented ovarian failure following treatment with CYC, these studies employed cessation of menses and an elevated FSH as the only indicators. Using this definition, an estimated 30% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) will develop ovarian failure following CYC, with older age and higher cumulative CYC dose as the most important predictors.

Although the average age of women at menopause is 51, the average age of last childbirth in societies that do not use contraception is 41, which indicates that menstrual bleeding persists for an average of 10 years in the absence of ovarian function capable of producing pregnancy.(3) Determining ovarian function based on menses therefore fails to provide sufficient information about fertility.

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), a marker of ovarian reserve primarily studied in the reproductive endocrinology literature, has now also gained favor in the chemotherapy literature based on its improved sensitivity profile relative to traditional FSH testing. In females, AMH is low at birth, rises during late puberty, then declines with age, becoming undetectable after both natural and surgical menopause.(7) Unlike FSH, AMH does not fluctuate significantly throughout the menstrual cycle.(5) Moreover, according to numerous observational studies of chemotherapy’s effects, decrements in AMH precede elevations in FSH.(10)

Whether AMH levels could rebound to a clinically significant degree over a long period of time following administration of CYC is not known. In this cohort, AMH was found to have increased by 0.5–0.8ng/ml in 2 women with 3 years of post-CYC follow-up. Anecdotal evidence suggests that women with apparent infertility for years to decades following CYC therapy may eventually conceive naturally. It cannot be determined, however, if this reflects a slow rise in AMH and ovarian viability, or if it reflects that while egg number is low, individual egg quality can still provide for the fortuitous happenstance that one of the remaining oocytes will be fertilized.

Unfortunately, this study does not provide sufficient data to determine the impact of oral contraceptives or GnRH agonists on ovarian preservation. Most prior studies of oral contraceptives during CYC therapy have not documented a protective effect.(11) GnRH-agonist co-therapy during CYC treatment, however, has been shown to prevent cessation of menstruation in both rheumatologic and oncologic studies.(12) How this protocol might affect fertility or AMH is less clear.

The dramatic decline in ovarian reserve with CYC therapy documented in this study suggests that physicians should consider alternate therapies for young women with vasculitis. Several options exist, including administration of intermittent IV rather than daily oral CYC; using the shortest course of CYC possible then switching to a medication that is less toxic to the ovaries; and consideration of rituximab therapy for young women. (13) The RAVE trial recently demonstrated that rituximab may be a viable option for young women who wish to preserve fertility but require treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis.(14) Other avenues for fertility preservation include co-therapy with GnRH agonists and cryopreservation of the ovary, oocytes, or embryos.

Access to a control group with GPA (though not of similar severity), use of a single ovarian-toxic medication, and use of AMH as a marker of subclinical ovarian damage confer particular importance on the results of this study. The primary drawbacks lie in the limited number of women without previous CYC exposure and the fact that this analysis was not planned prior to enrollment in WGET; as a result, blood draws were not timed to the menstrual cycle, thus making the FSH measurement less useful, and menstrual histories were not taken at the completion of the study. Due to the difference in primary outcome, these lapses have prevented direct comparison of the current study to other investigations of ovarian function in women with rheumatologic disease.

Nevertheless, this study strongly suggests that the administration of daily oral CYC for severe GPA results in ovarian damage among women of childbearing age. Efforts to minimize ovarian exposure to CYC may therefore help preserve fertility and delay menopause in women with vasculitis.

Significance and Innovation.

-

■

This study demonstrates that even low doses of daily oral cyclophosphamide can have a clinically significant and lasting impact on ovarian reserve in women with vasculitis.

-

■

Cyclophosphamide’s effect on ovarian reserve in women with vasculitis had not previously been assessed. The data from SLE patients treated with cyclophosphamide cannot reliably be applied to patients with vasculitis, given the difference in dosing methods (intermittent IV for SLE patients vs. daily oral for vasculitis patients).

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funded by a contract (N01-AR-9-2240) with the National Institutes of Health, National Instute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; a grant (FD-R-001652-01) from the Food and Drug Administraction Office of Orphan Products; General Clinical Research Center grants to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (M01-RR0-2719), Boston University (M01-RR0-00533), the University of Michigan (M01-RR-0042), and Duke University (M01-RR-30) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources; Amgen; and the Charles Hammond Research Fund of Duke University Medical Center’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. John C. Davis Jr. is employed by Genentech, Inc.

References

- 1.Park MC, Park YB, Jung SY, Chung IH, Choi KH, Lee SK. Risk of ovarian failure and pregnancy outcome in patients with lupus nephritis treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. Lupus. 2004;13:569–574. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu1063oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huong DL, Amoura Z, Duhaut P, et al. Risk of ovarian failure and fertility after intravenous cyclophosphamide. A study in 84 patients. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2571–2576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.te Velde ER, Pearson PL. The variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:141–154. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser JA, de Jong FH, Laven JS, Themmen AP. Anti-Mullerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. Reproduction. 2006;131:1–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanchin R, Taieb J, Lozano DH, Ducot B, Frydman R, Bouyer J. High reproducibility of serum anti-Mullerian hormone measurements suggests a multi-staged follicular secretion and strengthens its role in the assessment of ovarian follicular status. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:923–927. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, Scheffer GJ, et al. Serum antimullerian hormone levels best reflect the reproductive decline with age in normal women with proven fertility: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson SM, Messow MC, Wallace AM, Fleming R, McConnachie A. Nomogram for the decline in serum antimullerian hormone: a population study of 9,601 infertility patients. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.08.022. e1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sowers MR, Eyvazzadeh AD, McConnell D, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone and inhibin B in the definition of ovarian aging and the menopause transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3478–3483. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etanercept plus standard therapy for Wegener's granulomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:351–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lie Fong S, Lugtenburg PJ, Schipper I, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian function in women after chemotherapy and radiotherapy for haematological malignancies. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:674–678. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenfeld Z, von Wolff M. GnRH-analogues and oral contraceptives for fertility preservation in women during chemotherapy. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:543–552. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clowse MEB, Behera MA, Anders CK, et al. Ovarian preservation by GnRH agonists during chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Womens Health. 2009;18:311–319. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DR, et al. Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:670–680. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]