Abstract

This study examined whether the New Beginnings Program for divorced families led to improvements in youth’s educational goals and job aspirations six years following participation and tested whether several parenting and youth variables mediated the program effects. Participants were 240 youth aged 9–12 years at the initial assessment, and data were part of a randomized, experimental trial of a parenting skills preventive intervention targeting children’s post-divorce adjustment. The results revealed positive effects of the program on youth’s educational goals and job aspirations six years after participation for those who were at high risk for developing later problems at program entry. Further, intervention-induced changes in mother-child relationship quality and youth externalizing problems, internalizing problems, self-esteem, and academic competence at the six-year follow-up mediated the effects of the program on the educational expectations of high-risk youth. Intervention-induced changes in youth externalizing problems and academic competence at the six-year follow-up mediated the effects of the program on the job aspirations of high-risk youth. Implications of the present findings for research with youth from divorced families and for the public health burden of divorce are discussed.

It is well documented that parental divorce is associated with multiple problems for youth that extend into adulthood, including internalizing and externalizing problems, interpersonal difficulties, poor physical health, and substance use (e.g., Amato, 2001; Chase-Lansdale, Cherlin, & Kiernan, 1995). Several studies have found that parental divorce in childhood is also linked with negative educational and occupational outcomes across the life span, such as a decreased probability of graduating from high school, after controlling for income, parental educational attainment, ethnicity, and other demographic variables (e.g., Sandefur, McLanahan, & Wojtkiewitz, 1992; Sun & Li, 2008; Zill, Morrison, & Coiro, 1993). Also, youth who experienced parental divorce attain lower levels of education and obtain less prestigious occupations than those whose parents remained married (e.g., Biblarz & Gottainer, 2000; Caspi, Wright, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998; Hetherington, 1999). Further, Biblarz and Raftery (1999) found that parental divorce may contribute to a gradual decline in intergenerational socioeconomic status. Taken together, these findings suggest that the effects of parental divorce on educational and occupational attainment have significant public health implications.

There are a number of preventive interventions designed to improve children’s adaptation after parental divorce (e.g., Parenting Through Change, Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999; Martinez & Forgatch, 2001; Children of Divorce Intervention Program, Pedro-Carroll & Cowen, 1985; Divorce Adjustment Project, Stolberg & Cullen, 1983; New Beginnings Program, Wolchik, West, Westover, & Sandler, 1993; Wolchik et al., 2000; Wolchik et al., 2002). Despite the growing interest in the idea of health promotion in high-risk populations (Catalano, Hawkins, Berglund, Pollard, & Arthur, 2002), few researchers have examined the effects of preventive interventions on positive developmental outcomes. The latest Institute of Medicine (2009) report underscored the importance of considering developmental competencies, such as educational and occupational outcomes, given that they enable the individual to be successful in subsequent developmental tasks and maintain resilience when faced with adversity. The few evaluations of programs for children from divorced families that have measured program effects on educational outcomes found that program-induced improvements in parenting led to children’s enhanced academic functioning and achievement (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999; Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, & Winslow, 2007). Further, only one study has examined possible mechanisms through which these programs may affect educational outcomes. Zhou et al. (2008) found that improvements in effective discipline mediated the effects of their preventive intervention, the New Beginnings Program (NBP), on grade point average at the six-year follow-up when the youth were adolescents.

To date, researchers have not examined whether programs for youth from divorced families affect the formation of occupational and educational goals in adolescence, a critical developmental task (Barber & Eccles, 1992; Beal & Crockett, 2010; Card, Steel, & Abeles, 1980; Erikson, 1968) that provides the foundation for educational and job attainment in later developmental stages (Cheeseman Day & Newburger, 2002; Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, & Elliot, 2002). For instance, Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, Carter, and Elliot (2000) found that young adults’ academic goals predicted their later educational achievement. Also, Judge, Cable, Boudreau, and Bretz (1995) found that individuals who reported ambitious goals for their occupational futures experienced greater objective job success, earned more and received more promotions than those who were less goal-driven.

This study used data from the NBP, a randomized experimental trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families, to examine whether this program affected adolescents’ educational and occupational goals. A secondary goal was to examine whether mediators of the program effects on educational and occupational goals could be identified. Two aspects of positive parenting, mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline, and four aspects of youth behaviors, externalizing problems, internalizing problems, self-esteem, and academic competence and performance, were tested based on research linking them to parental divorce and educational or occupational goals and data showing that the NBP had a positive effect on these variables. Below, we biefly describe the effects of the NBP. Then, we present research that links divorce to the potential mediators and research linking the potential mediators to academic and occupational goals.

NBP

The NBP was developed to mitigate several negative outcomes associated with parental divorce, including children’s mental health problems, substance use, and social problems, by modifying risk and protective factors that have been linked with the negative post-divorce outcomes (Wolchik et al., 1993). A randomized experimental trial of the NBP, which included a mother program condition, a mother program plus child program condition, and a literature control condition, assessed both short-term and long-term effects. The trial found that the effects of the two conditions on mediators and outcomes at posttest and short-term follow-up did not differ (Wolchik et al., 2007). Thus, these two conditions have been combined in subsequent analyses of the NBP.

Program effects were found at posttest on mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, and mother/child report of children’s externalizing problems and internalizing problems (Wolchik et al., 2000). The six-year follow-up showed that adolescents in the NBP condition had fewer sexual partners, lower rates of mental disorder, lower levels of internalizing and externalizing problems and substance use, and higher grade point averages (GPA) and self-esteem than participants in the literature control condition (Wolchik et al., 2007). Many of the program effects at posttest and follow-up were stronger for those with higher levels of baseline risk (Dawson-McClure, Sandler, Wolchik, & Millsap, 2004; Wolchik et al., 2000; 2002; 2007).

Links between divorce, putative mediators, and educational and occupational outcomes

Divorce is associated with diminished parenting, including decreased levels of warmth and responsiveness, less effective communication, and the use of harsh or coercive discipline (e.g., Astone & McLanahan, 1991; Hetherington, Cox, & Cox, 1985; Simons & Johnson, 1996). Theory and research also suggests that quality of parenting is related to adolescents’ educational and occupational goals, aspirations, and engagement (Bryant, Zvonkovic, & Reynolds, 2006; Jodl, Michael, Malanchuk, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2001). For example, attachment theory proposes that, following the establishment of a secure caregiver base, children will feel safe and comfortable to explore their environments and individuate without risk to the parent-child bond (Ainsworth, 1989; Paquette, 2004). Eccles et al. (1993) further conceptualizes parents as providers of behavioral reinforcement, resources, and educational opportunities as children embark on their path to career success. Numerous studies have found support for an association between quality of parenting and youths’ educational and occupational goals, aspirations, and engagement (e.g., Astone & McLanahan, 1991; Barnard, 2004; Jodl et al., 2001; Rodgers & Rose, 2001). Illustratively, Schmitt-Rodermund and Vondracek (1999) found that parental involvement in children’s activities was prospectively related to more career exploration and planning in adolescence. Glasgow, Dornbusch, Troyer, Steinberg, and Ritter (1997) also showed that neglectful parenting predicted adolescents’ lowered educational expectations one year later.

It is well documented that children from divorced families are at an increased risk for externalizing behavior problems (e.g., Amato, 2000; 2001; Amato & Keith, 1991; Hetherington, 1993) and that these problems are linked with later negative academic and occupational outcomes, both in adolescence (e.g., Andrews & Duncan, 1997) and young adulthood (Fergusson & Horwood, 1998). Fergusson and Horwood (1998) proposed that early-onset externalizing problems may lead to substance abuse and association with deviant peers, which may contribute to a lack of life opportunities in the domains of education and work. Masten et al. (2005) proposed that conduct problems in childhood could impede learning and alienate teachers and peers, which may produce deficits in educational and occupational functioning later in life. Notably, Masten et al. (2005) found that childhood externalizing problems were linked with low academic achievement and competence seven years later, when participants were adolescents. Risi, Gerhardstein and Kistner (2003) also found that children’s aggression toward peers was related to a decreased probability of graduating high school 10 years later.

Parental divorce has also been shown to be related to children’s internalizing problems (e.g., Amato, 2000; 2001; Amato & Keith, 1991; Hetherington, 1993), but the support for the link between children’s internalizing problems and their educational and occupational outcomes is limited. Rapport, Denney, Chung, and Hustace (2001) found that anxiety and depression in childhood were related to later academic achievement, and that these relations were mediated through intellectual functioning and performance in the classroom. McLeod and Kaiser (2004) also showed that internalizing problems in school-aged children were related to a decreased likelihood of graduating from high school. Conversely, a number of studies have shown that externalizing problems in childhood were more predictive of later educational and occupational outcomes than were internalizing problems (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Masten et al., 2005; McLeod & Kaiser, 2004). Masten et al. (2005) proposed that mental health problems in childhood, whether internalizing or externalizing, can inhibit success with developmental tasks, such as educational and occupational goals, through their influence on disruptive behavior and lack of engagement in the classroom.

Studies have also shown that parental divorce is associated with lower self-esteem (Amato & Keith, 1991; Amato, 2001; Storksen, Roysamb, Moum, & Tambs, 2005) and decreased academic achievement during childhood and adolescence (e.g., Amato, 2001; Amato & Keith, 1991; Teachman, Paasch, & Carver, 1996). Researchers have demonstrated that both academic self-esteem and general self-esteem are linked to academic achievement and occupational goals (Ahmavaara & Houston, 2007; Emmanuelle, 2009; Pullmann & Allik. 2008). Theoretically, Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, and Vohs (2003) suggested that individuals with higher self-esteem will be more likely to persevere when faced with failure, and Wigfield and Eccles (1994) proposed that one’s belief in his or her abilities should determine expectations for success. Flouri (2006) showed that children’s self-esteem at age 10 was related to their educational attainment 16 years later. Trzesniewski et al. (2006) also found that adolescents’ low self-esteem was linked with a decreased likelihood of attending college and more work-related problems in adulthood. Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, and Pastorelli (2001) found adolescents’ academic self-efficacy was linked contemporaneously with academic performance and that academic self-efficacy and academic performance were related to the adolescents’ choice to pursue challenging careers one year later.

Contribution of the current study

This study extends previous research by examining whether a preventive intervention for youth from divorced families has positive effects on educational and occupational goals in adolescence. In addition, it examines whether program effects on educational and occupational goals are accounted for by program-induced changes in mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, and youth’s externalizing and internalizing problems, self-esteem, and academic achievement. Examining whether prevention programs have positive effects on educational and occupational goals and identifying the program components that mediate these changes have theoretical and applied implications (Ginexi & Hilton, 2006; Sandler, Wolchik, Winslow, & Schenck, 2006). Currently, 10 million children live in divorced or separated households (National Center for Health Statistics, 2005). Thus, identifying programs that affect educational and occupational goals of these youth could have important implications for reducing the public health burden of parental divorce. Further, identification of the components of the program that accounted for change in these outcomes can provide guidance for program refinement and dissemination (Kazdin & Nock, 2003).

This study advances existing knowledge in two important ways. First, it focuses on the developmental antecedents of occupational achievement and educational attainment in adulthood, which have significant implications for economic status and mental health throughout the lifespan (Cheeseman, Day & Newburger, 2002; Harackiewicz et al., 2002). Given the lack of previous research linking prevention programs and educational and occupational goals rather than educational attainment or occupational achievement, this study addresses a gap in the literature. Second, its use of data from a randomized trial allows a test of whether experimentally-induced changes in parenting and youth variables account for experimentally-induced effects on educational and occupational goals, thus strengthening the causal inference between these variables over those that can be drawn from previous work which has been correlational (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Cowan & Cowan, 2002; Rutter, 2005).

Method

Participants

Families were primarily recruited through divorce decrees obtained through public court records; about 20% of the sample responded to media advertisements. Participation was solicited by letters and follow-up phone calls to assess eligibility. Families that met eligibility criteria were asked to participate in an in-home recruitment visit. Eligibility criteria for participation in the trial included the child was living with the mother at least 50% of the time; the custody arrangement was expected to remain the same for the duration of the study; the divorce occurred within the last two years; the mother was not remarried, did not plan to remarry, and did not have a live-in partner; both mother and child were fluent in English; there was at least one child between the ages of 9 and 12 living in the home; and neither the mother nor child was currently receiving mental health services. In families that included more than one child between the ages of 9 and 12, one child was randomly selected for the interviews. Children who scored within the clinical range on measures of depression or externalizing problems or who endorsed current suicidal ideation were excluded and referred for treatment.

The sample consisted of 240 families that were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: mother-only program (MP) (n = 81 families), dual-component program (MPCP) (n = 83 families), or literature control condition (LC) (n = 76 families). Of the families contacted by phone, 48% (n = 671) met the initial eligibility criteria. Of these families, 68% (n = 453) completed the recruitment visit; 75% (n = 341) of the recruitment visit completers agreed to participate in the intervention study; 92% (n = 315) of these families completed the pretest. We found 16% (n = 49) to be ineligible at the pretest interview; an additional 8% (n = 26) withdrew before assignment. Thus, 36% (n =240) of the eligible families were randomly assigned to condition. Analyses revealed that participating families reported significantly higher incomes (p = .03) and maternal educational level (p = .01), and had fewer children (p = .01) than refusers (n = 59) (Wolchik et al., 2000; 2002). At the six-year follow-up, 218 (91%) families were interviewed. Attrition analyses comparing those who attrited between pretest and the six-year follow-up (N = 22) to those who remained in the study on baseline demographic variables and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems revealed no significant attrition or condition x attrition interaction effects (Wolchik et al., 2002), indicating that attrition did not pose a threat to internal or external validity.

At pretest, children were, on average, 10.34 years of age (SD = 1.1); 50% were female. Mothers’ ethnicity was 90% Caucasian, 6% Hispanic, and 4% other. Average annual household income was $20,001 - $25,000; 47% of the mothers had completed some college. Legal custody arrangements were 63%, 35%, and 3% sole maternal, joint, and split, respectively; families had been separated an average of 26.7 months and divorced an average of 12.3 months. Baseline equivalence between the experimental and control conditions in regard to children’s gender and age, mothers’ ethnicity, household income, length of time since separation and divorce, custody arrangements, and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems was examined, using χ2 tests for the categorical variables and t-statistics for the continuous variables. No significant differences were found.

In the families who participated in the six-year follow-up, youth were between the ages of 15 and 19 (M = 16.9, SD = 1.1); 49.5% were female. Mothers’ ethnicity was 89% Caucasian, 6% Hispanic, and 5% other. Average annual household income was $50,001 - $55,000. Legal custody arrangements were 53%, 46% and 1% sole maternal, joint, and paternal, respectively. Families had been separated an average of 8.4 years (SD = 1.4) and divorced an average of 7.2 (SD = .55) years.

Procedure

Families were interviewed on five occasions: pretest (T1), posttest (T2), and 3-month (T3), 6-month (T4), and 6-year (T5) follow-ups. The pretest occurred prior to randomization to condition. In the present study, data collected at T1, T2, and T5 were used. At each assessment, confidentiality was explained, parents (and at the six-year follow-up, adolescents 18 or older) signed consent forms, and children signed assent forms. Mothers and youth were interviewed separately. Families received $45 at pretest and posttest; at the six-year follow-up, parents and adolescents each received $100.

Experimental Conditions

The MP targeted positive parenting (i.e., mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline), interparental conflict, and mothers’ attitudes toward the father-child relationship. There were 11 group sessions (1.75 hour each); five focused on the quality of the mother-child relationship and three focused on effective discipline. Two individual sessions (1 hour each) focused on the mother’s use of the program skills with her children. Sessions were led by two Master’s-level clinicians and used didactic and experiential learning techniques that were based on social learning and cognitive behavioral research. The groups consisted of 8 to 10 mothers.

The MPCP consisted of concurrent but separate groups for children (CP) and mothers (MP). The 11 sessions in the CP targeted adaptive coping skills, negative cognitions, and mother-child relationship quality. Social learning and cognitive behavioral research provided a foundation for program exercises; didactic material was presented and modeled by group leaders or videotapes. Youth practiced the skills in the context of games, role-plays, and, for the communication skills, in a conjoint exercise with their mothers. Groups, which consisted of 8 to 10 children, were led by two Master’s-level clinicians. The MP in both conditions was identical, with the exception of the conjoint exercise on communication skills. Children and mothers in the LC each received three books about children’s post-divorce adjustment and a syllabus to guide their reading. See Wolchik et al. (2000, 2007) for more information about the conditions.

Measures

Demographics

Mothers responded to demographic questions such as their children’s age and living arrangement, and their own ethnicity, income, and level of education. Data taken from T1 were used in the analyses.

Mother-child relationship quality

Measures of mother-child relationship quality assessed at T1, T2, and T5 were used. Mothers and youth completed a revised version of the Acceptance (10 items) and Rejection (10 items) subscales of Schaefer’s (1965) Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Teleki, Powell, & Dodder, 1982). Parallel mother- and child-report versions were used. A sample item is “My mom isn’t very patient with me.” Coefficient alphas were acceptable (child report α’s for Acceptance = .82, .84, and .90; α’s for Rejection = .82, 81, and .86 at T1, T2, and T5; mother report α’s for Acceptance = .73, .77, and .82; α’s for Rejection = .74, .72, and = .73 at T1, T2 and T5, respectively). The rejection items were recoded and then the rejection and acceptance items were summed. CRPBI scores have been shown to distinguish between delinquent and normal children (Schaefer, 1965). Mothers and children completed the 10-item Open Communication subscale of the Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (Barnes & Olson, 1985). A sample item is “Mom is always a good listener.” Coefficient alpha’s were acceptable (child report α’s = .85 at T1, .87 at T2, .91 at T5; mother report α’s = .71 at T1, .72 at T2, .83 at T5). Scores on this measure have been positively linked with psychological adjustment in adolescents (e.g., Young & Childs, 1994). In addition, mothers and children completed an adaptation of the 7-item Dyadic Routine subscale of the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen, James, Boyce, & Hartnett, 1983). A sample item is “You had time each day just to talk with your kids.” Coefficient alpha’s were acceptable (mother report α’s = .66 at T1, .63 at T2, .84 at T5; child report α’s = .71 at T1, .76 at T2, .76 at T5). Scores on this measure and children’s adjustment problems have been shown to be negatively related (Cohen, Taborga, Dawson, & Wolchik, 2000). All measures used the time frame of the past month. The six measures were standardized and averaged to obtain a composite of mother-child relationship quality.

Effective discipline

Effective discipline scores at T1 and T2 were used; T5 scores were not used because the program did not affect discipline at T5. Mothers reported on inappropriate discipline (5 items; α’s = .75 at T1, .77 at T2), appropriate discipline (9 items; α’s = .59 at T1, .59 at T2), and discipline follow-through on the Oregon Discipline Scale (11 items; α’s = .78 at T1, .76 at T2; Oregon Social Learning Center, 1991). Sample items include “When your child misbehaved, how often did you yell?” (inappropriate discipline), “When your child misbehaved, how often did you restrict privileges?” (appropriate discipline), and “How often did you feel that it was more trouble than it was worth to punish your child?” (follow-through). Responses on the appropriate and inappropriate items were used to compute a ratio of appropriate-to-inappropriate discipline. Similar discipline measures have been shown to correlate with adolescents’ mental health problems (e.g., Patterson & Forgatch, 1995). Also, mothers and children completed the 8-item Inconsistency of Discipline subscale of Teleki et al.’s (1982) adaptation of the CRPBI (Schaefer, 1965), which used the time frame of the past month. A sample item is “It depended on your mother’s mood whether a rule was enforced or not.” Coefficient alphas were adequate (mother report α’s = .82 at T1, .80 at T2; child report α’s = .74 at T1, .73 at T2). These four scales were standardized and averaged to create a composite score.

Externalizing problems

Externalizing problems at T1, T2, and T5 were assessed using a composite of 33 mother-reported items (α’s = .88 at T1, .86 at T2, .89 at T5) from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991a; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981) and 30 child-reported items (α’s = .87 at T1, .83 at T2, .84 at T5) from the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991b). The time frame used was the last month. A sample item is “Argues a lot.” Scores on the CBCL and the YSR have been shown to distinguish children receiving psychological services from normal controls (Achenbach, 1991a). Mother- and child-reports were standardized and averaged to obtain a composite score. In addition, teachers completed the six-item acting out subscale (α’s = .90 at T1, .90 at T2, .89 at T5) of the Teacher-Child Rating Scale using the time frame of the last month; a sample item is “Disruptive in class.”

Internalizing problems

Internalizing problems at T1, T2, and T5 were measured using a composite of 31 mother-reported items (α’s = .88 at T1, .85 at T2, .86 at T5) from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991a; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981), 28 child-reported items (α’s = .88 at T1, .90 at T2, .89 at T5) from the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978), and 27 child-reported items (α’s = .81 at T1, .83 at T2, .85 at T5) from the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981). Sample items for these measures are “Likes to be alone” and “You worried a lot of the time,” and “I am sad once in a while”, for the CBCL, RCMAS and CDI, respectively. Scores on the RCMAS are correlated with other measures of anxiety in children, including the Trait Anxiety score from the State-Trait Anxiety Scale for Children (e.g., Carey et al., 1994). Scores on the CDI have been shown to differentiate children who are clinically depressed from non-depressed psychiatric child patients (e.g., Kovacs, 1985), and scores on the CBCL have been shown to differentiate children referred for psychiatric services from non-referred children (Achenbach, 1991a). A composite score of internalizing problems was created by standardizing and then averaging the three measures.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem scores at T1 and T5 were used; T2 scores were not used because the program did not affect self-esteem at T2. Youth completed the 6-item global self-esteem subscale of the Self-Perception Profile for Children (Harter, 1982; α’s = .78 at T1, .86 at T5). A sample item is “Some kids like the kind of person they are.” Scores on this measure have been negatively related to children’s depressive symptoms (Renouf & Harter, 1990).

Academic competence

Scores at T1 and T5 were used; T2 scores were not used because the program did not affect academic competence at T2. Mothers and children completed the 6-item academic competence subscale of the Coatsworth Competence Scale (Coatsworth & Sandler, 1993). Coefficient alphas were adequate (mother report α’s = .91 at T1, .90 at T5; child report α’s = .78 at T1, .81 at T5). Scores on this measure have been linked with other measures of competence and with mental health outcomes (Coatsworth & Sandler, 1993; Spaccarelli, Coatsworth, & Bowden, 1995). A sample item is “Your child had problems learning new subjects at school.” Mother- and child-report scores were standardized and then composited by taking the mean. In addition, adolescents’ cumulative unweighted grade point average (GPA) for all classes taken in high school was collected from school transcripts at T5. At T1, academic competence was assessed using only the Coatsworth measure. At T5, a composite was created by standardizing the scores for GPA and academic competence and averaging them.

Educational and occupational outcomes

At T5, educational expectations were assessed with the question “When you think about your future, what is the highest level of education you expect to attain?” from the Future Expectations Scale (Linver, Barber, & Eccles, 1997). The five response options ranged from completing high school to attending post-college graduate or professional school. To assess job aspirations, youth were presented with a list of 28 occupations and asked “If you could have any job you wanted, what job would you like to have when you are 30 years old?” (Possible Jobs Scale; Tucker, Barber, & Eccles, 1997). Occupations were subsequently scored according to level of prestige, with higher scores reflecting more (highest prestigious jobs).

Results

Analytical Procedure

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus software (Version 5.1 Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007) was used to evaluate the program effects on educational expectations and job aspirations and to test the mediation models. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation. FIML yields estimates that are less biased than the conventional listwise deletion or mean substitution in handling missing data (Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Program effects on educational expectations and job aspirations were examined separately. Following the establishment of program effects on the two outcomes, mediational analyses were conducted to identify potential mediators of these effects. Because previous analyses demonstrated that youth who were at greater baseline risk for developing future adjustment problems benefited from the program more than those at lower risk (e.g., Dawson et al., 2004; Wolchik et al., 2000; 2007), we first examined if the program x risk interaction effects on educational expectations and job aspirations were significant in accordance with Aiken and West’s (1991) multiple regression procedure. A moderated effect was considered to occur if the interaction was significant, and the Johnson-Neyman procedure (Potthoff, 1964) was employed to probe the region in which the intervention and control groups differed significantly on the outcome variables (see Aiken & West, 1991). We then conducted mediated moderation analyses (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007), assessing whether the mediation process accounted for this moderation. If the mediated moderation effect was significant, we probed the simple mediation effect following the procedure outlined in Tein et al. (2004). Specifically, we examined whether the mediation effect was significant at different levels of the moderator (e.g., one standard deviation below [−1SD] and one standard deviation above [+1SD] the mean). This procedure does not artificially dichotomize the sample into high and low risk groups and thus provides greater power for examining the simple effect. The baseline risk index consists of the baseline variables that were the strongest predictors of adolescent adjustment outcomes in the LC group: externalizing problems and a composite of environmental stress measures that assessed the following divorce-related stressors, child-experienced negative events, interparental conflict, decreased contact with father, per capita income, and maternal distress (see Dawson-McClure et al., 2004 for a more detailed description of this index).

Both three-wave longitudinal and two-wave half-longitudinal models (Cole & Maxwell, 2003) were employed to test mediation. In both approaches, the predictor was the program condition and the outcomes were educational expectations and job aspirations at 6-year follow-up. In the three-wave longitudinal models, the mediators were those for which positive program effects occurred at posttest: mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems. In the half-longitudinal models, the mediators, which were measured concurrently with the outcomes, were those variables for which positive program effects occurred at the 6-year follow-up: mother-child relationship quality, self-esteem, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and academic competence.

Separate mediation models were first tested for each mediator variable and each outcome variable. When significant effects were found for more than one mediator, multi-mediator models, which included each mediator that was significant in the single mediator models, were tested to determine whether there was unique prediction of the mediator above and beyond the other mediators. In all models, the baseline measures of the mediators were controlled. Because GPA was not measured at pretest or posttest, T1 academic competence was used as the baseline proxy of the T5 academic competence/GPA composite. Variables measured at the same assessment point were permitted to correlate with one another.

MacKinnon’s (2008) guidelines for mediation were used in which mediation is established if the path from the independent variable to the mediator (a path) and the path from the mediator to the outcome controlling for the independent variable (b path) are significant. According to the simulation study by Fritz and MacKinnon (2008), this method provides a more robust test of mediation than Baron and Kenny’s (1986) method that requires the path from the independent variable to the outcome without controlling for the mediator is also significant. In cases where the a and b paths were significant, the statistical significance of the mediation effect (a*b) was tested against the confidence interval, [CI: ab ± (significant critical value)*(SEab)], where SEab is the standard error using the PRODCLIN procedure (see Fritz and MacKinnon, 2008; MacKinnon, 2008). If zero is not contained within the 95% CI, it can be concluded that the mediated effect is significant.

Preliminary Analyses

A Box’s M analysis, including all of the study variables, was conducted to determine whether the MP and MPCP conditions could be combined as they were in previous studies (Wolchik et al., 2007; Velez, Wolchik, Tein & Sandler, in press; Zhou et al., 2008). The Box’s M analysis is considered a conservative omnibus test that assesses whether the variance and covariance matrices of two groups differ significantly (Winer, 1971). If Box’s M is nonsignificant, it can be concluded the relations among the variables do not differ significantly across groups. The results showed that the variance/covariance matrices did not differ significantly (Box’s M = 5.63; F(3) = 1.85, p = .14; χ2(3) = 5.54, p = .14). Thus, the MP and MPCP conditions were combined for the analyses. Dummy codes were created for the LC (0) and MP + MPCP (1) conditions. The diagnostic indices of leverage (Mahalanobis’ distance), distance, and influence (DFFITS and Cook’s Distance) were calculated to identify potential outliers or influential data points (Cook, 1977; Neter, Kutner, & Wasserman, 1989; Stevens 1984). These analyses revealed no outliers or influential data points; thus all cases were retained in the analyses.

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are provided in Table 1, and the correlations among the study variables and potential covariates are presented in Table 2. The following variables were selected as potential covariates based on previous research indicating that they were significantly related to the mediator or outcome variables: child’s age and gender, mother’s and father’s highest level of education, months since separation, and months since divorce. A path from the covariate to the outcome or the mediator was included in the SEMs that examined program effects or mediation effects if the zero-order correlation of the covariate with the outcome or the mediator was significant. If the path from the covariate to the mediator or the outcome was nonsignificant in the model, the covariate was dropped.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Variables

| Measure | Mean Total |

Mean 0 | Mean 1 | SD Total | SD 0 | SD 1 | Skewness Total |

Skewness 0 |

Skewness 1 |

Kurtosis Total |

Kurtosis 0 |

Kurtosis 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | ||||||||||||

| 1. Group | .68 | -- | -- | .47 | -- | -- | −.79 | -- | -- | −1.38 | -- | -- |

| 2. Gender | .51 | .49 | .52 | .50 | .50 | .50 | −.05 | .05 | −.10 | −2.01 | −2.05 | −2.02 |

| 3. Risk | .00 | −.19 | .09 | 1.00 | .87 | 1.05 | .54 | .60 | .46 | .36 | .95 | .15 |

| 4. Months Divorce |

12.23 | 12.43 | 12.13 | 6.41 | 6.39 | 6.43 | .07 | .06 | .08 | −1.07 | −1.15 | −1.04 |

| 5. Child Age | 10.35 | 10.26 | 10.38 | 1.12 | 1.06 | 1.15 | .25 | .34 | .20 | −1.31 | −1.10 | −1.40 |

| 6. Father Ed. | 4.62 | 4.61 | 4.62 | 1.52 | 1.43 | 1.56 | −.41 | −.52 | −.37 | −.78 | −.49 | −.88 |

| 7. Mother Ed. | 5.00 | 4.93 | 5.04 | 1.17 | 1.10 | 1.20 | −.55 | −.24 | −.67 | .25 | −.17 | .44 |

| T2 | ||||||||||||

| 8. MC Rel Qual. |

.34 | .26 | .38 | .59 | .59 | .59 | −.28 | −.10 | −.38 | −.64 | −.95 | −.43 |

| 9. Discipline | .46 | .30 | .53 | .61 | .62 | .59 | −.39 | −.27 | −.45 | −.14 | −.39 | .07 |

| 10.MC Int Prob. |

−.46 | −.39 | −.49 | .72 | .77 | .69 | .72 | .90 | .58 | .47 | 1.12 | −.10 |

| 11.MC Ext. Prob. |

−.26 | −.22 | −.28 | .75 | .76 | .74 | .47 | .01 | .71 | .43 | −.31 | .93 |

| 12. T Ext. Prob. | .08 | .05 | .09 | .99 | .88 | 1.04 | 1.44 | 1.27 | 1.48 | 1.39 | .75 | 1.45 |

| T5 | ||||||||||||

| 13.MC Rel. Qual. |

.22 | .21 | .22 | .92 | .92 | .92 | −.71 | −.47 | −.82 | .23 | −.90 | .78 |

| 14. MC Ext. Prob. |

−.25 | −.17 | −.28 | .93 | 1.09 | .84 | .59 | .75 | .35 | .75 | .76 | .18 |

| 15.MC Int. Prob. |

−.39 | −.35 | −.40 | .87 | .94 | .85 | 1.00 | 1.46 | .72 | 1.82 | 3.45 | .75 |

| 16. T Ext. Prob. | .08 | .29 | −.02 | .95 | 1.12 | .84 | 1.67 | 1.32 | 1.83 | 2.25 | 1.15 | 2.72 |

| 17.Acad. Com. | −.08 | −.18 | −.03 | .97 | 1.02 | .95 | −.63 | −.54 | −.68 | −.24 | −.02 | −.35 |

| 18. S. Esteem | 19.91 | 19.88 | 19.93 | 3.57 | 4.08 | 3.32 | −.64 | −.87 | −.45 | −.30 | −.09 | −.67 |

| 19.Job Aspir. | 18.32 | 17.29 | 18.79 | 6.40 | 6.33 | 6.40 | −.41 | −.13 | −.55 | −.62 | −.95 | −.36 |

| 20.Ed. Expect. | 4.06 | 4.05 | 4.06 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 | −1.22 | −1.52 | −1.11 | 1.47 | 2.43 | 1.13 |

Note. Group: 0 = control; 1 = intervention. Gender (of child): 1 = female; 2 = male. Months Divorce = months since divorce. Mother Ed. And Father Ed. = highest level of education completed (1 = elementary, 2 = some high school, 3 = high school grad, 4 = technical school, 5 = some college, 6 = college grad, 7 = graduate school). MC Rel. Qual. = mother-child relationship quality. MC Ext. Prob. = mother/child-reported externalizing problems. MC Int. Prob. = mother/child-reported internalizing problems. T Ext. Prob. = teacher-reported externalizing problems. Total N ranged from 174 to 240.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations: Study Variables and Covariates

| Measure | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | 19. | 20. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Group | -- | .03 | .13 | −.02 | .05 | .00 | .04 | .10 | .18** | −.07 | −.04 | .02 | .01 | −.06 | −.03 | −.15* | .07 | .02 | .11 | .01 |

| 2. Gender |

-- | .18** | −.03 | .10 | .04 | −.03 | −.07 | −.00 | .01 | .09 | .31** | −.18** | .02 | −.05 | .20** | −.13 | .01 | −.14* | −.18** | |

| 3. Risk | -- | −.03 | −.03 | −.30** | −.16* | −.32** | −.28** | .44** | .63** | .32** | −.19** | .35** | .24** | .18* | −.28** | −.20** | −.08 | −.26** | ||

| 4. Months Divorce |

-- | −.03 | .06 | .01 | .01 | .02 | −.02 | −.02 | .01 | .11 | −.09 | −.02 | .03 | .09 | .15* | .17* | .12 | |||

| 5. Child Age |

-- | .07 | −.15* | −.13 | .02 | .04 | .10 | −.14* | −.02 | .00 | .01 | −.07 | −.01 | −.00 | −.04 | −.01 | ||||

| 6. Father Ed. |

−− | .31** | .04 | .10 | −.15* | −.14* | −.12 | .09 | −.10 | −.06 | −.20** | .40** | .08 | .22** | .21** | |||||

| 7. Mother Ed. |

-- | .05 | .18** | −.04 | −.08 | −.02 | −.04 | −.09 | −.03 | −.04 | .16* | −.01 | .12 | .16* | ||||||

| T2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. MC Rel. Qual. |

−− | .56** | −.41** | −.50** | −.11 | .38** | −.17* | −.14* | −.09 | .16* | .15* | .04 | .06 | |||||||

| 9. Discip. |

-- | −.30** | −.37** | −.09 | .22** | −.17* | −.04 | −.11 | .22** | .10 | .06 | .09 | ||||||||

| 10.MC Int. Prob. |

-- | .62** | .02 | −.08 | .31** | .43** | .16* | −.16* | −.32** | .03 | −.14* | |||||||||

| 11.MC Ext. Prob. |

-- | .25** | −.22** | .44** | .31** | .31** | −.27** | −.28** | −.06 | −.20** | ||||||||||

| 12. T Ext. Prob. |

-- | −.19** | .25** | .05 | .35** | −.24** | .00 | −.07 | −.15* | |||||||||||

| T5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 13.MC Rel. Qual. |

-- | −.37** | −.27** | −.23** | .29** | .33** | .19** | .29** | ||||||||||||

| 14. MC Ext. Prob. |

-- | .59** | .40** | −.49** | −.42** | −.20** | −.35** | |||||||||||||

| 15. MC Int. Prob. |

-- | .19* | −.33** | −.63** | −.04 | −.23** | ||||||||||||||

| 16. T Ext. Prob. |

-- | −.42** | −.20** | −.11 | −.23** | |||||||||||||||

| 17.Acad. Comp. |

-- | .32** | .36** | .48** | ||||||||||||||||

| 18. Self Esteem |

-- | .18** | .33** | |||||||||||||||||

| 19.Job Aspir. |

-- | .48** | ||||||||||||||||||

| 20.Ed. Expect. |

-- | |||||||||||||||||||

Note. Group: 0 = control; 1 = intervention. Gender (of child): 1 = female; 2 = male. Months Divorce = months since divorce. Mother Ed. and Father Ed. = highest level of education completed (1 = elementary, 2 = some high school, 3 = high school grad, 4 = technical school, 5 = some college, 6 = college grad, 7 = graduate school). MC Rel. Qual. = mother−child relationship quality. Discip. = effective discipline. MC Ext. Prob. = mother/child−reported externalizing problems. MC Int. Prob. = mother/child−reported internalizing problems. T Ext. Prob. = teacher−reported externalizing problems. N for correlations ranged from 174 to 240.

p< .01

p< .05

As shown in Table 2, age was significantly correlated with T2 teacher-reported externalizing problems, such that younger children exhibited higher levels of externalizing problems. Gender was significantly correlated with T2 and T5 teacher-reported externalizing problems, such that boys scored higher than girls. Gender was also significantly correlated with T5 mother-child relationship quality, T5 educational expectations and T5 job aspirations, with males having lower scores than females on these measures. Mothers’ level of education was significantly positively correlated with T2 effective discipline, T5 academic competence, and T5 educational expectations. Fathers’ level of education was significantly positively correlated with T2 mother/child-reported internalizing problems, T5 academic competence, T5 teacher-reported externalizing problems, T5 educational expectations and T5 job aspirations. Fathers’ level of education was significantly negatively correlated with T2 mother/child-reported externalizing problems. Time since divorce was significantly positively correlated with T5 self-esteem and T5 job aspirations; adolescents whose parents had been divorced longer had higher self-esteem and higher job aspirations.

Analyses of Program Effects

In the model in which educational expectations was the outcome, program, risk, and the program x risk interaction were included as predictors, and child gender and mother’s and father’s highest level of education were included as covariates based on the results of the correlational analyses. Mothers’ level of education became nonsignificant and was thus dropped from the model. Although the program main effect was nonsignificant (β = .05, p = .41), the program x risk interaction effect was significant (β = .39, p < .01). The Johnson-Neyman procedure (Aiken & West, 1991) revealed that for youth who had risk scores beyond 1.14 SD above the mean, the intervention and control conditions differed significantly, such that youth in the intervention had higher expectations than those in the control condition. Approximately 12% of the sample was in this region.

In the model in which job aspirations was the outcome, program, risk, and the program x risk interaction were included as predictors, and child gender, time since divorce, and father’s level of education were included as covariates based on the results of the correlational analyses. Similar to the findings of educational expectations, the program main effect was nonsignificant (β = .12, p = .07) and the path from program x risk to job aspirations was significant (β = .28, p < .05). The Johnson-Neyman procedure revealed that for youth who had risk scores beyond .56 SD above the mean, the intervention and control conditions differed significantly, such that the youth in the intervention had higher aspirations than those in the control condition. Approximately 26% of youth in the sample were in this region.

Mediation Models

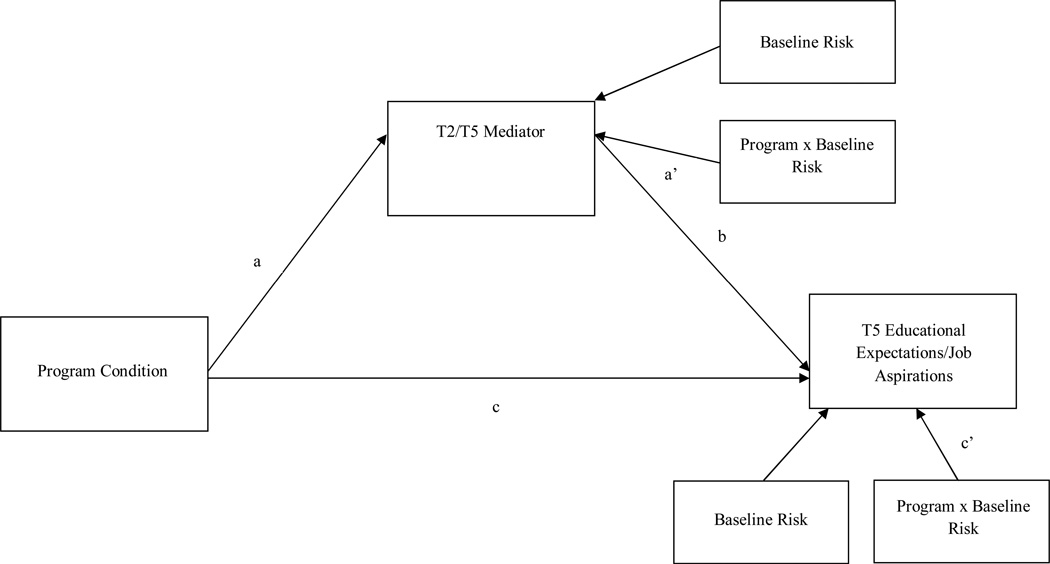

Because the program effects on the two outcomes were moderated by the baseline risk, we conduced mediated moderation analyses, which included program x risk interactions to the mediator (a’ path) and the outcome (c’ path) in the SEM. Figure 1 illustrates a theoretical mediation model.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Mediation Model.

Three-wave longitudinal models

Figure 1 illustrates a theoretical mediation model. Table 3 shows the results of the mediation models in which the program effects on T5 measures of educational expectations and job aspirations were mediated by the prospective effect of the five potential mediators measured at T2: mother-child relationship quality, effective discipline, mother/child-reported internalizing problems, mother/child-reported externalizing problems, and teacher-reported externalizing problems. As shown, all the mediation models fit the data adequately. The program had significant effects (a path) on all of the mediators except teacher-reported externalizing problems. Risk did not moderate any of the program effects on the mediators (a’ path). After controlling for the program effect, none of the mediators had significant effects on educational expectations or job aspirations (b path). The direct effects from the program x risk interaction to the two outcomes remained significant (c’ path). Because none of the models had significant a (or a’) and b paths, the mediated effects were not assessed for significance.

Table 3.

Summary of the Three-Wave Longitudinal Models - Program → T2 Mediator → T5 Outcome

| Outcome Variable | Mediator Variable | a | a’ | b | c | c’ | χ2 | df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T5 future educational expectations | T2 mother-child relationship quality | .17** | .07 | −.05 | .07 | .37** | 3.47 | 2 | .06 | .01 | .99 |

| T2 effective discipline | .22** | .03 | .01 | .06 | .37** | .63 | 2 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T2 mother/child-report intern. prob.- | .11* | −.10 | −.04 | .06 | .37** | 3.15 | 2 | .05 | .01 | .99 | |

| T2 mother/child-report extern. prob-. | 13** | −.07 | −.07 | .04 | .39** | .22 | 3 | .00 | .00 | 1.00 | |

| T2 teacher-report extern. problems -. | 01 | −.11 | −.11 | .06 . | 38** | .67 | 1 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T5 job aspirations | T2 mother-child relationship quality | .17* | .07 | −.11 | .17* | .33* | .19 | 3 | .00 | .00 | 1.00 |

| T2 effective discipline | .22** | .03 | −.08 | .14* | .28* | .80 | 3 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T2 child/mother-report intern. prob. | −.11* | −.10 | .09 | .13* | .28* | 3.82 | 4 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T2 child/mother-report extern. prob.- | .13** | −.08 | −.04 | .11 | .28* | .49 | 4 | .00 | .00 | 1.00 | |

| T2 teacher-report extern. problems | −.01 | −.11 | −.01 | .12 | .28* | 3.28 | 4 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 |

Note. a’ = program x risk interaction on mediator. c’ = program x risk interaction effect on outcome. Confidence interval 95%.

p< .01

p< .05

Two-wave half-longitudinal models

Table 4 shows the results of the mediation models in which the program effects on educational expectations and job aspirations were mediated by the concurrent effects of the six T5 potential mediators: mother-child relationship quality, mother/child-reported internalizing problems, mother/child-reported externalizing problems, teacher-reported externalizing problems, academic competence, and self-esteem. All of the mediation models fit the data adequately. There were significant program x risk interaction effects (a’ path) on all of the mediators beyond the significant main effects (a path) on mother/child-reported and teacher reported externalizing problems. With the exception of teacher-reported externalizing problems, all the mediators had a significant effect (b path) on educational expectations. Only mother/child-reported externalizing problems and academic competence had a significant effect (b path) on job aspirations.

Table 4.

Summary of the Two-Wave Half-Longitudinal models - Program → T5 Mediator → T5 Outcome

| Outcome Variable | Mediator Variable | a | a’ | b | c | c’ | LCL | UCL | χ2 | df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T5 future educational expectations | T5 mother-child relationship quality | .08 | .26* | .21** | .06 | .33* | .007 | .102 | .34 | 1 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 |

| T5 mother/child-report intern. prob. | −.09 | −.48** | −.15* | .04 | .31* | .007 | .117 | 3.27 | 3 | .02 | .02 | 1.00 | |

| T5 mother/child-report extern. prob | −.15* | −.53** | −.29** | .01 | .25 | −.267 | −.063 | 1.02 | 3 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T5 teacher-report extern. problems | −.18** | −.37** | −.12 | .03 | .36** | 3.21 | 2 | .05 | .02 | .98 | |||

| T5 academic competence/GPA | .12 | .34** | .46** | .00 | .26* | .052 | .232 | .09 | 2 | .00 | .00 | 1.00 | |

| T5 self-esteem | .07 | .56** | .26** | .05 | .23 | .036 | .174 | 1.27 | 2 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T5 job aspirations | T5 mother-child relationship quality | .08 | .26* | .06 | .13* | .30* | 4.93 | 2 | .07 | .02 | .97 | ||

| T5 mother/child-report intern. prob. | −.09 | −.48** | .01 | .12 | .28* | 4.59 | 4 | .03 | .02 | .99 | |||

| T5 mother/child-report extern. prob | −.15* | −.53** | −.17* | .09 | .20 | .011 | .193 | 2.43 | 4 | .00 | .01 | 1.00 | |

| T5 teacher-report extern. problems | −.18** | −.35* | −.01 | .12 | .27* | 3.16 | 3 | .02 | .02 | 1.00 | |||

| T5 academic competence/GPA | .12 | .33** | .35** | .09 | .18 | .035 | .183 | 6.90 | 3 | .07 | .02 | .96 | |

| T5 self-esteem | 07 | .56** | .13 | .11 | .21 | 6.23 | 4 | .05 | .02 | .96 |

Note. a’ = program x risk interaction on mediator. c’ = program x risk interaction effect on outcome. LCL and UCL were calculated for marginal and significant mediation effects. Confidence interval 95%.

p< .01

p< .05

For those models that had both significant a’ (indicating that the program effects on the mediators were moderated by risk) and b paths, simple mediation effects were tested. The findings of the simple mediation effects indicated that for youth with high, but not low risk, significant mediation effects were found for mother-child relationship quality (95% CI: .0068, .1022), self-esteem (95% CI: .0361, .1740), mother/child-reported externalizing problems (95% CI: −.2666, −.0633), mother/child-reported internalizing problems (95% CI: .0073, .1174), and academic competence (95% CI: .0522, .2324) on educational expectations. Significant mediation effects also occurred for academic competence (95% CI: .0353, .1832) and mother/child-reported externalizing problems (95% CI: .0107, .1927) on job aspirations for high risk youth.

To assess the unique mediation effect of each mediator, mother-child relationship quality, self-esteem, mother/child-reported externalizing problems, mother/child-reported internalizing problems, and academic competence were entered simultaneously into the SEM predicting educational expectations. The fit of the model was satisfactory: χ2 (35) = 44.63, p = .13, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .03, CFI = .98. All the a’ paths remained significant: program x risk to mother-child relationship quality, β = .26, p = .03; to self-esteem, β = .53, p = .00; to mother/child-reported externalizing problems, β = -.54, p = .00; to mother/child-reported internalizing problems, β = -.50, p = .00; to academic competence, β = .34, p = .01. The b paths from academic competence (β = .41, p = .00) and from self-esteem (β = .19, p = .02) to educational expectations were significant. The paths from the other three mediators were nonsignificant. Probing of the simple mediation effects indicated that academic competence (95% CI: .0421, .2088) and self-esteem (95% CI: .0129, .1450) independently accounted for the effects of the program on educational expectations for the high-risk youth.

Academic competence and mother/child-reported externalizing problems were entered simultaneously into the SEM predicting job aspirations to assess for unique mediation effects. The fit of the model was satisfactory: χ2 (9) = 10.29, p = .33, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .02, CFI = .99. Both a’ paths remained significant: program x risk to academic competence (β = .33, p = .01); to externalizing problems (β = -.53, p = .00). The b path from academic competence (β = .27, p = .00) to job aspirations was significant; the path from externalizing problems was nonsignificant. Probing of the simple mediation effects indicated that academic competence independently accounted for the program effects on job aspirations (95% CI: .0223, .1537) for the high-risk youth.

Discussion

This study examined whether a parenting-focused intervention for divorced families affected youth’s educational expectations and occupational aspirations six years following participation and tested whether several parenting and youth variables mediated the program effects. The results indicated that, for adolescents who were at high initial risk for developing later problems, those in the program had both higher expectations for their educational attainment and higher job aspirations compared to their counterparts in the control condition. None of the posttest variables examined mediated the effects of the program on educational expectations and occupational aspirations. However, mother-child relationship quality as well as youth externalizing and internalizing problems, self-esteem and academic competence at the six-year follow-up mediated the effects of the program on high-risk adolescents’ educational expectations. Also, measures of academic competence and externalizing problems at the six-year follow-up mediated the effects of the program on job aspirations for high-risk adolescents. When the significant mediators were entered simultaneously into the models predicting educational expectations and job aspirations to assess for unique mediated effects, only academic competence remained a significant mediator of program effects on job aspirations. Both self-esteem and academic competence uniquely mediated the effects of the program on educational expectations.

This is the first study to examine the effects of a preventive intervention on the educational goals and occupational aspirations of youth in divorced families. The findings extend the results of previous studies, which have shown that prevention programs improved risky behaviors, substance use and mental health outcomes, and academic performance of youth in divorced families (DeGarmo et al., 2004; Pedro-Carroll & Alpert-Gillis, 1997; Pedro-Carroll, Sutton, & Wyman, 1999; Wolchik et al., 2000; 2002; 2007), to include a domain of functioning that has significant consequences for adult educational and occupational success (Cheeseman Day & Newburger, 2002; Harackiewicz et al., 2002). In the context of the consistent finding that youth from divorced families exhibit lower achievement in the domains of work and education (e.g., Biblarz & Gottainer, 2000; Hetherington, 1999) and experience more economic difficulties (Caspi et al., 1998), these findings have important implications for reducing the public health burden of divorce. The finding that program effects occurred for youth who were at high risk, but not low risk, of developing mental health and other problems is consistent with a growing body of research on the effects of prevention programs (e.g., Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, 2009; Stoolmiller, Eddy, & Reid, 2000; Wolchik et al., 2000; 2007). Screening for level of risk may be an effective way to increase the likelihood of benefits of interventions for divorced families (Dawson-McClure et al., 2004).

It is important to note that support for meditational relations only occurred in the models in which the mediators and outcomes were measured concurrently. Thus, the significant pathways must be viewed as providing preliminary support for meditational relations (Kraemer, Yesavage, Taylor & Kupfer, 2000). Prospective mediational effects were not found for any of the posttest measures. It is possible that mediational pathways would have been detected if the time lag between the posttest and follow-up assessments had been shorter than six years. It is also possible that variables that were not assessed at post-test, such as monitoring and supervising of school-related activities, school performance, and completion of homework, may be related to occupational and educational goals in mid-to-late adolescence.

Several dyadic and youth variables assessed at the six-year follow-up mediated the effect of the NBP on the educational expectations of high-risk youth. The mediational effect for mother-child relationship quality is consistent with previous work with this data set that has shown mediational effects of this variable for internalizing and externalizing problems and mental disorder symptom count (Zhou et al., 2008). Supportive parenting may provide adolescents with the confidence and self-worth necessary to develop ambitious long-term educational goals. The mediational relations between academic competence and educational expectations are consistent with previous studies linking academic achievement in middle and high school with later educational outcomes (Huurre, Aro, Rahkonen, & Komulainen, 2006; Strenze, 2007). These findings suggest that successful academic experiences may lead youth to aspire to achieve ambitious goals later in life. The mediational pathway for self-esteem and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems are consistent with research showing associations between self-esteem (Ahmavaara & Houston, 2000; Emmanuelle, 2009), internalizing problems (McLeod & Kaiser, 2004; Rapport et al., 2001), externalizing problems (Asendorpf, Denissen, and van Aken, 2008; Masten et al., 2005) and academic outcomes. It is possible that high self-esteem affects persistence in mastering academic tasks, which then affect educational goals. Similarly, aggressive or withdrawn behavior may prevent adolescents from learning effectively in school and inhibit positive relationships with teachers (Masten et al., 2005). These processes may affect academic performance, which then influences educational goals. It is notable that the effect of externalizing problems was obtained for mother/child-reported but not teacher-reported externalizing problems. One explanation for the difference in findings across reporters is that the high school teachers observed the adolescents for only one class period per day, which may have restricted the range of behaviors they could observe.

Academic competence and mother/child-reported externalizing problems assessed at the six-year follow-up mediated the effects of the NBP on high-risk adolescents’ job aspirations. These findings are consistent with research linking academic success with later career success and socioeconomic attainment (Strenze, 2007) and suggest that career goals may be one mechanism through which school grades in adolescence contribute to later occupational attainment. In the multiple mediator models, only academic competence uniquely mediated program effects on educational expectations and job aspirations for high-risk youth. The lack of the contribution of the other variables may be due in part to the small sample size. A larger sample may be required to detect smaller mediation effects when multiple mediators are tested.

The current study has limitations that can inform future research. First, given that all significant findings were found for the models where the mediators and outcomes were measured concurrently, it is not possible to draw causal inferences (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). It is possible that educational and occupational goals affect the hypothesized mediating variables or that there are reciprocal relations between educational and occupational goals and the proposed mediators. Future research that includes assessments in which the potential mediators have temporal precedence but are more proximal to the outcomes than those in the current study are needed to identify causal relations. Second, the sample was almost exclusively Caucasian and middle-class. Studying the effects of this program and others for youth from divorced families on educational and occupational goals using samples that are diverse in terms of ethnicity and socioeconomic background is an important future direction.

Implications for Theory and Intervention

The current study demonstrated that a prevention program for divorced families had longitudinal effects on the educational expectations and occupational aspirations of high-risk adolescents, and that these program effects were partially mediated through program-induced effects on academic achievement, self-esteem, externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and the quality of the mother-adolescent relationship. The finding of long-term effects of this program on educational and occupational goals highlights the importance of including follow-up assessments to identify both enduring effects and outcomes that are specific to developmental stages that occur after program participation. There is considerable evidence suggesting that the benefits of preventive interventions continue to unfold over time (DeGarmo et al., 2004; Gillham, Reivich, Jaycox, & Seligman, 1995; Wolchik et al., 2007). Further, the findings of this study underscore the need to study the effects of prevention programs on educational and occupational goals, as these outcomes have been previously linked to performance and attainment outcomes in these domains (Harackiewicz et al., 2000; Judge et al., 1995). To our knowledge, the current study represents the first test of the effects of a preventive intervention on educational and occupational goals and aspirations, and it is also one of the few studies linking these outcomes with youth self-esteem, internalizing and externalizing problems, and the mother-child relationship.

Summary

Children from divorced families are at an increased risk for decreased academic and occupational achievement, relative to their peers from non-divorced families (Biblarz & Gottainer, 2000; Caspi et al., 1998; Hetherington, 1999). The findings from the current study indicated that the educational and occupational goals of high-risk adolescents from divorced families were enhanced through a preventive intervention that focused on improving parenting skills. In addition, these findings suggest that intervention-induced effects on several intrapersonal and interpersonal risk and protective factors, such as self-esteem, academic competence, externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and mother-child relationship quality, were associated with improvements in high-risk adolescents’ educational expectations and occupational aspirations. These results suggest that the public health burden due to divorce may be reduced through the widespread implementation of parenting-focused preventive interventions for this at-risk population

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelock CS. Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four through sixteen. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1981;46(1):82–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont,Department of Psychology; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmavaara A, Houston DM. The effects of selective schooling and self-concept on adolescents’ academic aspiration: An examination of dweck’s self-theory. itish Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;77(3):613–632. doi: 10.1348/000709906X120132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MS. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44(4):709–716. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2000;62(4):1269–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(3):355–370. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Duncan SC. Examining the reciprocal relation between academic motivation and substance use: Effects of family relationships, self-esteem, and general deviance. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;20(6):523–549. doi: 10.1023/a:1025514423975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, Denissen JJA, van Aken MAG. Inhibited and aggressive preschool children at 23 years of age: Personality and social transitions into adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(4):997–1011. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astone NM, McLanahan SS. Family structure, parental practices and high school completion. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(3):309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Vittorio Caprara G, Pastorelli C. Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development. 2001;72(1):187–206. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BL, Eccles JS. Long-term influence of divorce and single parenting on adolescent family- and work-related values, behaviors, and aspirations. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(1):108–126. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard WM. Parent involvement in elementary school and educational attainment. Children and Youth Sciences Review. 2004;26(1):39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Development.Special Issue: Family Development. 1985;56(2):438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal SJ, Crockett LJ. Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(1):258–265. doi: 10.1037/a0017416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz TJ, Gottainer G. Family structure and children’s success: A comparison of widowed and divorced single-mother families. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2000;62(2):533–548. [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz TJ, Raftery AE. Family structure, educational attainment, and socioeconomic success: Rethinking the “pathology of matriarchy.”. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105(2):321–365. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant BK, Zvonkovic AM, Reynolds P. Parenting in relation to child and adolescent vocational development. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2006;69(1):149–175. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11(1):59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JJ, Steel L, Abeles RP. Sex differences in realization of individual potential for achievement. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1980;17(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Faulstich ME, Carey TC. Assessment of anxiety in adolescents: Concurrent and factorial validities of the trait anxiety scale of spielberger’s state-trait anxiety inventory for children. Psychological Reports. 1994;75(1):331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Wright E, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Early failure in the labor market: Childhood and adolescent predictors of unemployment in the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review. 1998;63(3):424–451. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Berglund L, Pollard JA, Arthur MW. Prevention science and positive youth development: Competitive or cooperative frameworks? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(6):230–239. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale P, Cherlin AJ, Kiernan KK. The long-term effects of parental divorce on the mental health of young adults: A developmental perspective. Child Development. 1995;66(6):1614–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman Day J, Newburger EC. The big payoff: Educational attainment and synthetic estimates of work-life earnings. Current Population Report, US Census Bureau. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth D, Sandler IN. Multi-rater measurement of competence in children of divorce; Williamsburg VA. Paper presented at the biennial conference of the Society for Community Research and Action.1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Taborga M, Dawson S, Wolchik SA. Do family routines buffer the effects of negative divorce events on children’s symptomatology?; Montreal Canada. Poster presented at the Society for Prevention Research; 2000, June. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam C. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(4):330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RD. Detection of influential observations in linear regression. Technometrics. 1977;19:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Interventions as tests of family systems theories: Marital and family relationships in children’s development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(4):731–759. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-McClure SR, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Millsap RE. Risk as a moderator of the effects of prevention programs for children from divorced families: A six-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An Official Publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2004;32(2):175–190. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019769.75578.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. How do outcomes in a specified parent training intervention maintain or wane over time? Prevention Science. 2004;5(2):73–89. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000023078.30191.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Arberton A, Buchanan CM, Janis J, Flanagan C, Harold R, MacIver D, Midgley C, Reuman D. School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self-perceptions, and activity choices. University of Neaska Press; 1993. pp. 145–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuelle V. Inter-relationships among attachment to mother and father, self-esteem, and career indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;75(2):91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. Oxford, England: Norton & Co; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E. Parental interest in children’s education, children’s self-esteem and locus of control, and later educational attainment: Twenty-six year follow-up of the 1970 itish birth cohort. itish Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;76(1):41–55. doi: 10.1348/000709905X52508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(5):711–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. A graphical representation of the mediated effect. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(1):55–60. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham JE, Reivich KJ, Jaycox LH, Seligman MEP. Prevention of depressive symptoms in schoolchildren: Two-year follow-up. Psychological Science. 1995;6(6):343–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ginexi EM, Hilton TF. What’s next for translation research? Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2006;29(3):334–347. doi: 10.1177/0163278706290409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow KL, Dornbusch SM, Troyer L, Steinberg L, Ritter PL. Parenting styles, adolescents’ attributions, and educational outcomes in nine heterogeneous high schools. Child Development. 1997;68:507–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harackiewicz JM, Barron KE, Tauer JM, Carter SM, Elliot AJ. Short-term and long-term consequences of achievement goals: Predicting interest and performance over time. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92(2):316–330. [Google Scholar]

- Harackiewicz JM, Barron KE, Tauer JM, Elliot AJ. Predicting success in college: A longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94(3):562–575. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53(1):87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM. An overview of the Virginia longitudinal study of divorce and remarriage with a focus on early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;7(1):39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM. Social capital and the development of youth from nondivorced, divorced and remarried families. In: Collins WA, Laursen B, editors. Relationships as developmental contexts. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999. pp. 177–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Cox M, Cox R. Long-term effects of divorce and remarriage on the adjustment of children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1985;24(5):518–530. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huurre T, Aro H, Rahkonen O, Komulainen E. Health, lifestyle, family and school factors in adolescence: Predicting adult educational level. Educational Research. 2006;48(1):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young prople: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EW, James SA, Boyce WT, Hartnett SA. The family routines inventory: Development and validation. Social Science & Medicine. 1983;17(4):201–211. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodl KM, Michael A, Malanchuk O, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. Parents’ roles in shaping early adolescents’ occupational aspirations. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1247–1265. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge TA, Cable DM, Boudreau JW, Bretz RD. An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel Psychology. 1995;48(3):485–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(8):1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Depressive disorders in childhood: II. A longitudinal study of the risk for a subsequent major depression. Annual Progress in Child Psychiatry & Child Development. 1985;41(7):520–541. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790180013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica: International Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1981;46(5–6):305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Kupfer D. How can we learn about developmental processes from cross-sectionsl studies, or can we? The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):163–171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]