Abstract

Objective. To compare the effects of aggressive tight control therapy and conventional care on radiographic progression and disease activity in patients with early mild inflammatory arthritis.

Methods. Patients with two to five swollen joints, Sharp–van der Heijde radiographic score (SHS) <5 and symptom duration ≤2 years were randomized between two strategies. Patients with a definite non-RA diagnosis were excluded. The protocol of the aggressive group aimed for remission (DAS < 1.6), with consecutive treatment steps: MTX, addition of adalimumab and combination therapy. The conventional care group followed a strategy with traditional DMARDs (no prednisone or biologics) without DAS-based guideline. Outcome measures after 2 years were SHS (primary), remission rate and HAQ score (secondary).

Results. Eighty-two patients participated (60% ACPA positive). In the aggressive group (n = 42), 19 patients were treated with adalimumab. In the conventional care group (n = 40), 24 patients started with hydroxychloroquin (HCQ), 2 with sulfasalazine (SSZ) and 14 with MTX. After 2 years, the median SHS increase was 0 [interquartile range (IQR) 0–1.1] and 0.5 (IQR 0–2.5), remission rates were 66 and 49% and HAQ decreased with a mean of −0.09 (0.50) and −0.25 (0.59) in the aggressive and conventional care group, respectively. All comparisons were non-significant.

Conclusion. In patients with early arthritis of two to five joints, both aggressive tight-control therapy including adalimumab and conventional therapy resulted in remission rates around 50%, low radiographic damage and excellent functional status after 2 years. However, full disease control including radiographic arrest in all patients remains an elusive target even in moderately active early arthritis.

Trial registration. Dutch Trial Register, http://www.trialregister.nl/, NTR 144.

Keywords: early arthritis, rheumatoid, TNF, treatment strategy, management, trial, STREAM

Introduction

The early and aggressive treatment of patients with RA is increasingly successful, particularly with combinations of DMARDs containing anti-TNF therapy [1–5]. Among the results are percentages of sustained remission of ∼40%, excellent functional status and nearly complete arrest of radiological damage progression. In an attempt to explain these better results than had been attained before in RA of longer duration, the concept of a window of opportunity was proposed, suggesting that early suppression of active inflammation produces long-term benefits [6].

Intensive therapy, preferably with a combination of drugs, therefore, is a well-established treatment strategy for patients with early active RA. However, the optimal strategy for patients presenting with only a few inflamed joints is not yet clear. This category of patients is more difficult to study due to the problem of classifying these patients as having RA or undifferentiated arthritis (UA) [7]. In recognition of this issue, a combined task force of ACR and EULAR has developed new classification criteria for RA [8]. One of the objectives of these criteria is to increase the sensitivity for the diagnosis RA in early UA in order to facilitate the conduction of clinical trials in this category of patients. Other aspects to consider in trials in this group of patients are that around half of patients with UA will remit within 1–2 years [9–13], that it is inherently less possible to demonstrate a reduction of an already low disease activity, and finally that any toxicity of treatment is less acceptable since it is occurring in patients with only mildly active disease.

In a preceding study, we have shown that patients with more severe forms of UA are under-treated in comparison with patients with RA [9]. One clinical trial has shown that UA patients treated with MTX vs placebo have less progression to RA (according to 1987 ACR criteria [14]) and less progression of radiographic erosions, but these differences were confined to the subgroup of ACPA-positive patients [15]. On the other hand, in early RA good results can also be obtained with the milder drug hydroxychloroquin (HCQ) [16]. The present 2-year trial [Strategies in Early Arthritis Management (STREAM)] investigated whether the approach of early aggressive therapy was also effective in arthritis patients presenting with only moderately active disease, i.e. in those patients who would not meet the usual inclusion criteria for trials in active RA.

Patients and methods

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years, with a symptom duration of ≤2 years. In addition, they had to have two to five swollen joints and a total Sharp–van der Heijde radiographic score (SHS) [17] <5. Patients did not have to meet the 1987 ACR criteria for RA. Exclusion criteria were prior treatment with a DMARD, except for HCQ, the use of CSs in the last 3 months or an IA injection with CSs in the last month. In addition, patients with bacterial arthritis, crystal-induced arthritis, PsA, ReA, OA or arthritis due to sarcoidosis or another systemic autoimmune disease other than RA, as well as pregnant patients and patients with a wish to conceive during the study were excluded. The patients were recruited from the rheumatology clinics of the Jan van Breemen Institute and the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The study was approved by the local institutional review board [Medisch Ethische Toetsingscommissie van Slotervaartziekenhuis en Reade (formerly Jan van Breemen Institute)] and all patients gave written informed consent. The trial registration number is NTR 144.

Study design and treatment algorithm

The study was designed as analogous to the Behandel Strategieën (BeSt) study of treatment strategies in early active RA [3], and compared two treatment strategies in a single-blind clinical trial. Whereas in the BeSt study the criterion for a change of therapy was a DAS >2.4, here we used a lower DAS threshold for a change of therapy of 1.6, as disease activity is inherently lower in this group of patients. Also, the goal of the intervention was to achieve and maintain remission, which is defined as a DAS < 1.6 [18].

The patients were randomized in blocks of 10 into one of two treatment groups: (i) aggressive therapy and (ii) conventional care. In the aggressive group, therapy was aimed at achieving and maintaining a DAS (44-joint score) of <1.6, which is considered to represent remission [18]. Every 3 months the DAS was performed by a research nurse who was blinded to the allocated treatment group. Treatment was started with oral MTX 15 mg/week. If the DAS was ≥1.6 at a given time point, the therapy was changed (see also Table 1). The predefined steps were: increase in MTX to 25 mg/week; MTX 25 mg/week combined with adalimumab 40 mg/2 week; MTX 25 mg/week combined with adalimumab 40 mg/week; a combination of MTX 25 mg/week, SSZ 2000 mg/day and HCQ 400 mg/day; a combination of MTX 25 mg/week, SSZ 2000 mg/day, HCQ 400 mg/day and prednisone 7.5 mg/day; leflunomide (LEF) 20 mg/day and i.m. gold 50 mg/week. If the DAS was <1.6 at one time point the treatment remained unchanged. If the DAS was <1.6 at two consecutive time points the following actions were taken, depending on the treatment step where the patient was at that moment: MTX 15 mg/week was decreased from 2.5 mg/2 weeks to 0 mg/week after 3 months; MTX 25 mg/week was decreased from 2.5 mg/2 weeks to 10 mg/week after 3 months; adalimumab 40 mg/2 weeks was stopped; adalimumab 40 mg/week was decreased to 40 mg/2 weeks; HCQ was decreased from 200 mg/8 weeks to 0; if remission was sustained after 3 months SSZ was decreased subsequently from 500 mg/4 weeks to 0; if remission was sustained after 3 months MTX was decreased from 2.5 mg/2 weeks to 0; prednisone 7.5 mg/day was decreased to 0 mg in 7 weeks; LEF was decreased to 10 mg/day; and if remission was sustained after 3 months LEF was stopped; gold was decreased to 50 mg/2 weeks, if DAS remained <1.6; and gold was decreased to 50 mg/4 weeks; if remission was sustained, gold was stopped. If at any time point the DAS was ≥1.6 the last effective treatment was restarted. In case of intolerance to a DMARD, the highest tolerated dose was used and, if DAS was ≥1.6 at the next visit, the patient went on to the next step.

Table 1.

Flow diagram of the possible consecutive treatment steps in the aggressive (tight control) group

| Aggressive group (n = 42) | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| MTX 15 mg/week | |

| ↓ | |

| MTX 25 mg/week | 29 |

| ↓ | |

| Adalimumab 40 mg/2 weeks + MTX 25 mg/week | 19 |

| ↓ | |

| Adalimumab 40 mg/week + MTX 25 mg/week | 15 |

| ↓ | |

| MTX 25 mg/week + SSZ 2000 mg/day + HCQ 400 mg/day | 11 |

| ↓ | |

| MTX 25 mg/week + SSZ 2000 mg/day + HCQ 400 mg/day + prednisone 7.5 mg/day | 3 |

| ↓ | |

| LEF 20 mg/day (100 mg at Day 1, 8 and 15) | 1 |

| ↓ | |

| Gold i.m. 50 mg/week | 0 |

| ↓ | |

| Treating rheumatologist's preference | 0 |

Therapy was aimed at achieving and maintaining a DAS (44-joint score) <1.6. If the DAS was ≥1.6 at a given time point, the therapy was changed according to this scheme. If the DAS was <1.6 at one time point the treatment remained unchanged. If the DAS was <1.6 at two consecutive time points medication was tapered. The column on the right shows the number of patients reaching the corresponding treatment step during follow-up.

Conventional care was treatment according to the treating rheumatologist's preference. The rheumatologist had access to the DAS, but was not prompted to make treatment decisions based on the DAS. In order to maintain a certain amount of homogeneity in the treatment of the conventional care group, and to maintain contrast between the groups in terms of therapy, the following order of drugs was suggested to the treating rheumatologist: HCQ, SSZ, MTX and LEF. Furthermore, the treating physician could only change therapy if the DAS was >2.4 at the 3-month assessment time points and after consulting the trial supervisor (D.vS.). During the course of the inclusion period (June 2004–2007), the conventional care of RA became more aggressive in general. Therefore, from August 2005 onwards, after the inclusion of 25 patients, the treating physician was allowed to start therapy with MTX in the conventional care group if deemed necessary. IA CS injections were not regulated.

Assessments

Every 3 months the DAS was assessed by a research nurse. Questionnaires for physical function, i.e. the HAQ [19] and short-form 36 (SF-36) [20] were completed yearly. Side effects were documented and divided into adverse events or serious adverse events. Serious adverse events were defined as any adverse reaction resulting in any of the following outcomes: a life-threatening condition or death, a significant or permanent disability, a malignancy, hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization, a congenital abnormality or a birth defect. Radiographs of hands, wrists and feet were obtained at baseline, 1 and 2 years. All radiographs were read separately by two experienced rheumatologists, who were unaware of the identity of the patient and of the treatment group, and the mean values were used. The radiographs were read according to time sequence and scored according to the Sharp–van der Heijde method [17]. Before reading the trial radiographs, the two readers (D.vS. and Dr Pieter Prins) separately read 22 sets of radiographs of hands and feet from which an intra-class correlation coefficient of 95% was calculated. BMD of the femoral neck and spine was assessed by DXA at baseline and 2 years. The trial physician (I.C.vE.) verified adherence to the protocol every 3 months. All protocol deviations were recorded.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the progression of radiographic joint damage at 2 years. Radiographic progression was assessed in two manners: the absolute difference in Sharp score [17, 21] and the development of new erosions between baseline and 2 years. Erosions were diagnosed if any individual joint incorporated in the SHS showed bone cortex disruption on radiographs of hands and/or feet in anteroposterior projection. Secondary endpoints included differences between the two treatment strategies after 2 years regarding DAS, the percentage of patients in clinical remission (DAS < 1.6), HAQ and adverse events.

Sample size and statistical analysis

For the sample size calculation we looked at the appearance of new erosions in the first 2 years of treatment in 152 patients of the early arthritis clinic of the Jan van Breemen Institute who had two to five swollen joints and no erosions at their first visit in the period before the design of the study (1995–2003). Since SHSs were not available for this group, we used the radiologist's report and found a frequency of 37%. We hypothesized a frequency of new erosions of 10% in the aggressive group and calculated a sample size of 80 (α = 0.05, Zb = 0.824, n = 38 per group leads to power 80%).

Missing data for the primary and secondary endpoints were treated as follows: absence of a radiograph of hand and feet or HAQ score at 2 years was defined as missing. If a patient developed erosions on radiographs at 1 year but the 2-year radiographs were missing, that patient was included in the analysis as erosion developer. If a DAS score at 2 years was lacking it was replaced by the DAS score at 21 months (the principle of last observation carried forward) if available, otherwise it was missing. All available data were included for intention-to-treat analysis. Six patients had follow-up radiographs at 1 year but not at 2 years. Of these, four had radiographs taken after 3 years, and these were unchanged in comparison with the radiographs at 1 year. Therefore the radiographic scores in these four patients were analysed as if the radiographs had been taken at 2 years. Data are expressed as mean (s.d.) or median (range) as appropriate. Student's t-test was used to compare continuous normally distributed variables between groups. Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests were used when appropriate. For dichotomous variables, Pearson's chi-square test was used. A two-tailed probability value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P-values were not adjusted for multiple statistical tests.

Results

Patient characteristics

Randomization of 82 patients created generally balanced groups (aggressive group n = 42, conventional care group n = 40), with a mean age of 47 years and a mean symptom duration of 6 months (Table 2). ACPA was present equally in both groups. In the aggressive group, there was a higher percentage of RF positivity and of fulfilment of the 1987 ACR criteria for RA, whereas in the conventional care group there was a higher mean DAS and CRP. Two patients in the aggressive group discontinued adherence to the protocol within 3 months after randomization (but were not lost to follow-up): one patient decided directly after randomization not to take any anti-rheumatic drugs and one patient stopped taking MTX after an episode of fever that required hospitalization and was ascribed to MTX use. As this took place in the first year of the trial, two extra patients were randomized and both were allocated to the aggressive group, which explains why there were 42 patients in the aggressive group and 40 in the conventional care group (see also Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the tight control and conventional care group

| Characteristic | Tight control (n = 42) | Conventional care (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 48 (13) | 46 (12) |

| Gender: female, % | 58 | 79 |

| Disease duration, months | 6 (3–10) | 6 (4–9) |

| IgM-RF positive, % | 48 | 33 |

| ACPA positive, % | 60 | 60 |

| DAS (44 joints) | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.7) |

| CRP, mg/l | 6 (2–10) | 9 (3–21) |

| HAQ score | 0.50 (0.25–0.88) | 0.69 (0.32–1.06) |

| Fulfilment of 1987 ACR criteria for RA,% | 36 | 25 |

| Fulfilment of 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria for RA,% | 69 | 68 |

Values are presented as mean (s.d.) or median (IQR), as applicable.

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram.

Treatment

In the aggressive group, 19 (45%) patients were eventually treated with adalimumab starting after a median of 9 months (Table 1); of these, 4 reached remission and 11 continued with the next step, 3 were still treated with adalimumab at 2 years and 1 patient did not continue adalimumab for fear of injections. One patient was treated with LEF starting at 15 months, and none reached the i.m. gold step (Table 1). In the conventional care group, 24 patients started with HCQ (subsequently 5 switched to SSZ and 8 to MTX), 2 with SSZ and 14 with MTX (Table 3). The mean dose of MTX among MTX users in this group was 19 mg/week. In the conventional care group, a significantly higher number of patients received CS injections during follow-up (18 IA and 4 i.m. injections in 13 patients in the conventional care group vs 7 IA and 3 i.m. injections in two patients in the aggressive group, P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Medication prescribed in the conventional care group

|

This table depicts the initial therapy and number of patients receiving that therapy in the conventional care group at baseline (first column), treatment steps within the trial period (second and third columns) and the therapy and number of patients receiving that therapy at 2 years (fourth column).

Radiography

The median SHS increase between 0 and 2 years was 0 (IQR 0–1.0) in the entire aggressive group and 0.25 (IQR 0–2.5) in the entire conventional care group (P = 0.17). A cumulative probability plot of radiographic progression in the two groups is shown in Fig. 2. A baseline erosion with SHS < 5 (thus allowing inclusion) was present in three patients of the aggressive group and in six patients of the conventional care group. New erosions developed in 5 (13%) of 39 patients starting without erosions in the aggressive group, and in 8 (24%) of 34 patients starting without erosions in the conventional care group (P = 0.25). Data on the primary endpoint, radiographic damage at 2 years, were initially lacking in six patients. However, in four we were able to retrieve films taken at a later date. In all of these, the score was the same as that at 1 year, allowing imputation. The two remaining patients were in the conventional treatment group: both had moved out of the area. Their SHS scores at 1 year were 0 and 4.5 (baseline score 2), respectively. In two worst-case scenario analyses, we assumed (i) both patients had SHS progression at 2 years; and (ii) the first patient developed new erosions (the other patient had baseline erosions, and thus was excluded from this analysis). The results remained non-significant (both analyses, P = 0.15).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative probability plot of radiographic progression. Radiographic progression (Sharp/van der Heijde units) at 2 years compared with baseline in the tight control group (open dots) and conventional care group (closed dots). Every dot represents a patient. The dotted line is set at 5 Sharp/van der Heijde units as the minimal clinically important difference.

Eight patients (three in the aggressive group and five in the conventional care group) had an SHS increase of ≥5. The characteristics of this subgroup of patients compared with the patients with an SHS increase <5 are shown in Table 4. Six of the eight patients received high-dose MTX (22.5–25 mg/week), in one case also adalimumab, for most of the time. Three patients (all in the conventional care group) had an SHS increase of >14 points. Two of them were treated with high-dose MTX, one from 1 year onward and one from 18 months onward. All three were in DAS remission during at least four of eight measurements after baseline with a mean DAS of 1.5. The primary endpoint (SHS progression and erosion development) was also analysed in two subgroups of patients fulfilling the 1987 ACR criteria for RA, and fulfilling the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria for RA. In these subgroups the differences between the aggressive and conventional care groups were unaltered (data not shown). In addition, BMD was similar in the study groups and was not different for change or difference between groups (data not shown).

Table 4.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the subgroups of patients with a delta SHS < 5 and a delta SHS ≥5 at 2 years compared with baseline

| Characteristic | delta SHS < 5 (n = 68) | delta SHS ≥ 5 (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 48 (40–55) | 36 (31–55) |

| Gender: female, n (%) | 48 (67) | 7 (88) |

| Disease duration, months | 5 (3–9) | 7 (4–11) |

| IgM-RF positive, % | 42 | 38 |

| Anti-CCP positive, % | 57 | 88 |

| DAS (44 joints) | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | 2.4 (1.8–2.7) |

| CRP, mg/l | 8 (3–15) | 7 (2-14) |

| HAQ score | 0.63 (0.25–1.0) | 0.88 (0.13–1.0) |

| Fulfilment of 1987 ACR criteria for RA,% | 29 | 50 |

| Fulfilment of 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria for RA,% | 68 | 88 |

Values are presented as mean (s.d.) or median (IQR), as applicable.

Disease activity, remission and functionality

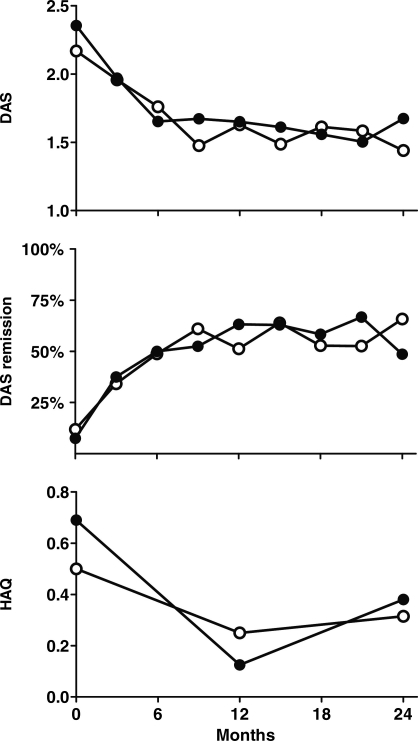

Mean DAS in the aggressive group at 0 and 2 years was 2.2 (0.52) and 1.4 (0.70), respectively, and 2.4 (0.65) and 1.7 (0.83), respectively, in the conventional care group (Fig. 3, upper). Mean DAS over the 2-year period (time-averaged DAS) was 1.60 (0.60) and 1.63 (0.58) in the aggressive and conventional care groups, respectively (P = 0.80). Remission rates in the aggressive group at 1 and 2 years were 54 and 66%, respectively, and 65 and 49% in the conventional care group (Fig. 3, middle). Seven (17.9%) patients in the aggressive group and six (15.8%) patients in the conventional care group reached a period of medication-free remission (P = 0.80). The median duration of medication-free remission was 6 months in the aggressive group and 7.5 months in the conventional care group with a range of 3–9 and 3–12 months, respectively. In the aggressive group, two of seven patients had reactivation of disease activity after medication-free remission and restarted treatment with MTX. In the conventional group, all patients remained medication free until the end of the trial. The mean HAQ decrease at 2 years compared with baseline was 0.09 (0.50) in the aggressive group and 0.25 (0.59) in the conventional care group (P = 0.6) (Fig. 3, bottom).

Fig. 3.

Secondary endpoints for DAS and HAQ in the aggressive group and the conventional care group. Upper: mean DASs at each time point. Middle: remission rates (percentage of patients with DAS < 1.6) at each time point. Bottom: median HAQ scores at baseline, 1 and 2 years. Open dots represent the tight-control group and closed dots represent the conventional care group.

A total of 28 protocol violations for varying reasons were recorded, all in the aggressive group. Nineteen violations were recorded due to not proceeding to the next treatment step with a low DAS score just above 1.6, nine violations were caused by not tapering medication after a third DAS <1.6. All comparisons were statistically non-significant, both for the primary and the secondary outcome measures.

Subgroup analysis for ACPA-positive patients

Due to the growing recognition of the importance of ACPA as a prognostic marker of RA, we added a subgroup analysis including only the ACPA-positive patients. In general, the groups were comparable. Although median SHS scores at 2 years and change of SHS score between baseline and 2 years tended to be higher in the conventional care group, values remained low and not significantly increased compared with the aggressive group [1 (0–2.5) and 1.5 (0–4) (P = 0.4) for median SHS scores at 2 years and 0 (0–2.4) and 0.5 (0–3.5) (P = 0.3) for change of SHS score between baseline and 2 years, in the aggressive group and conventional care group, respectively].

Adverse events

In the aggressive group, 59% of the patients experienced at least one adverse event during the follow-up period vs 42% in the conventional care group (P = 0.08). The total number of adverse events was significantly higher in the aggressive group vs the conventional care group (62 vs 35, P = 0.034). Eight serious adverse events in seven patients were documented: five in the aggressive group and three in the conventional care group. Four were medication related: three hospitalizations in the aggressive group and one in the conventional care group. In the aggressive group, one patient was hospitalized for fever during MTX therapy, classified as drug-induced fever. Another patient was hospitalized twice: once for fever during adalimumab therapy and once for active RA and a rash based on acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, attributed to adalimumab. In the conventional care group, one patient was hospitalized for gastrointestinal problems, which were attributed to MTX therapy.

Discussion

In this trial of an aggressive vs a conventional approach to early arthritis of two to five joints, most patients had an excellent outcome with respect to disease activity, functionality and radiographic damage regardless of the treatment group they were randomized to. A minority of patients in both groups experienced radiographic progression despite treatment with higher dose MTX and despite being in remission at most time points. There were also a substantial number of adverse events, especially in the aggressive group.

The radiological results (Fig. 2) give rise to the expectation that the difference between the groups would have been significant (in favour of the aggressive group) if the sample size had been larger, thus suggesting a lack of statistical power. In addition, not all patients had radiographs at the 2-year point. In our view, the main reason for the lack of statistically significant differences in the outcome parameters between the groups is that the gradual intensification of the conventional care during the course of the study, including a higher number of CS injections in that group, led to less contrast in therapy between the groups and to a lower than originally expected rate of radiographic damage in the conventional care group (24% observed instead of 37% expected new erosions), whereas the aggressive group achieved a 13% rate of new erosions, which is near to the 10% that had been assumed for the power calculation. The general trend in the treatment of (rheumatoid) arthritis is towards earlier and more aggressive treatment. At the time the study was designed in 2003, both study arms were acceptable for the participating rheumatologists. During the study, however, the conventional care needed to be intensified to accommodate changing views, and presently even the aggressive arm is considered to be not so aggressive, since adalimumab therapy was postponed until 6 months in non-responders. Furthermore, although ACPA positivity was equal among the groups, the study was not designed to separately analyse ACPA-positive and -negative subgroups, which were less prominently seen as important subgroups during the design phase of the study.

There were some drawbacks to using DAS-steered treatment aiming for remission (DAS < 1.6). Three patients had significant radiographic progression, although they were in DAS remission most of the time. As has been noted before, clinical remission is no guarantee for radiological remission [22], although a recent review showed that patients who achieve remission, defined in any way, will generally develop less radiological damage and deterioration of physical function compared with patients not reaching remission [23]. Secondly, it occurred a few times during the course of the study that patients without any swollen joints would proceed to the next step of high-dose MTX or adalimumab because they had a DAS ≥1.6 due to a high value of the DAS component of patient-reported general health. In a number of cases, based on this, the treating physician refused to intensify treatment. In light of the intensity of treatment needed to achieve these results, the number of adverse events that occurred (in both groups, but more so in the aggressive group) calls to mind the task of the physician to weigh the possible benefits of treatment against the possibility of causing harm. A related issue is the value of the DAS as a measure of remission in RA; although the DAS can be >1.6 while joints are neither swollen nor tender, the opposite also occurs: a patient reaches DAS remission in the presence of tender and/or swollen joints. In this case, one might better speak of minimal disease activity rather than remission [24]. Although most patients treated with biologic therapies seem to experience a virtual halt of radiographic progression, regardless of disease activity, even with biologic agents, a slight progression of joint damage can be observed with increasing disease activity [25, 26]. A problem is that current methods, such as the SHS, for identifying progression are insensitive in the setting of very low progression rates, since the smallest detectable difference is 5 SHS points [21]. Furthermore, clinical methods are also unreliable in the setting of very low disease activity. Subclinical joint inflammation, which can be detected by US and MRI in patients in clinical remission can mostly explain any ongoing radiographic progression [27]. It therefore remains possible that the observed reduction in association between disease activity and radiological damage is in fact explained by subclinical synovitis. This brings up the question, what is real remission? For this purpose, the ACR and EULAR have recently constituted a committee charged with the task to redefine remission in RA [28].

Other trials in early oligoarthritis or UA have noted some benefit from treatment with i.m. or IA CSs compared with placebo or NSAIDs [29, 30], although a recent study observed that neither remission nor development of RA was delayed by i.m. glucocorticoid treatment [31]. Three months of infliximab did not prevent progression to RA [32] after 1 year, nor did abatacept monotherapy [33], although abatacept had an impact on radiographic and MRI inhibition, which was maintained for 6 months after treatment stopped. MTX was successful in postponing the diagnosis of RA after 1.5 years, as well as in retarding radiological damage [15]. The positive results of the latter study were confined to the subgroup of ACPA-positive patients. In these trials, adverse events were generally not a problem.

Since the present study has not demonstrated a functional or radiological benefit of aggressive over conventional treatment, we cannot recommend aggressive therapy in all patients presenting with two to five swollen joints. The benefit of aggressive treatment in early inflammatory arthritis is not as evident as it is in polyarthritis, and many patients achieved good results, including prevention of erosive disease, with HCQ only, as has been found before in early RA [16, 34]. The treatment of oligoarthritis should ideally depend on an accurate prediction of prognosis. The most important prognostic factors are ACPA and radiographic damage [35]. These data, combined with the results of the present study, may suggest that in patients with early inflammatory arthritis a radiographic-driven therapy may be superior to the widely used DAS-driven therapy in reducing structural joint damage, but more research is needed to further refine prediction and thus guide therapy at the individual level.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Pieter Prins for reading radiographs and the research nurses Mrs Elleke de Wit-Taen, Mrs Veronique van de Lugt and Mrs Anne-Marie Abrahams for collecting clinical data.

Funding: The study was financially supported by Abbott.

Disclosure statement: B.A.C.D. has received research grants from Schering Plough, Abbott and Wyeth. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Markusse HM, et al. Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine with sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1997;350:309–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korpela M, Laasonen L, Hannonen P, et al. Retardation of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis by initial aggressive treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2072–81. doi: 10.1002/art.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:406–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hetland ML, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Junker P, et al. Aggressive combination therapy with intra-articular glucocorticoid injections and conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in early rheumatoid arthritis: second-year clinical and radiographic results from the CIMESTRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:815–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders SA, Capell HA, Stirling A, et al. Triple therapy in early active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, single-blind, controlled trial comparing step-up and parallel treatment strategies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1310–7. doi: 10.1002/art.23449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Dell JR. Treating rheumatoid arthritis early: a window of opportunity? Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:283–5. doi: 10.1002/art.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symmons DP, Silman AJ. Aspects of early arthritis. What determines the evolution of early undifferentiated arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis? An update from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:214. doi: 10.1186/ar1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1580–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen LM, van Schaardenburg D, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, et al. One year outcome of undifferentiated polyarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:700–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.8.700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison BJ, Symmons DP, Brennan P, et al. Natural remission in inflammatory polyarthritis: issues of definition and prediction. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:1096–100. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.11.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tunn EJ, Bacon PA. Differentiating persistent from self-limiting symmetrical synovitis in an early arthritis clinic. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:97–103. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Speyer I, Visser H, et al. Diagnosis and course of early-onset arthritis: results of a special early arthritis clinic compared to routine patient care. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:1084–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.10.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe F, Ross K, Hawley DJ, et al. The prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis and undifferentiated polyarthritis syndrome in the clinic: a study of 1141 patients. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:2005–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Dongen H, Van Aken J, Lard LR, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in patients with probable rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1424–32. doi: 10.1002/art.22525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matteson EL, Weyand CM, Fulbright JW, et al. How aggressive should initial therapy for rheumatoid arthritis be? Factors associated with response to ‘non-aggressive’ DMARD treatment and perspective from a 2-yr open label trial. Rheumatology. 2004;43:619–25. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Heijde DM, van Leeuwen MA, van Riel PL, et al. Biannual radiographic assessments of hands and feet in a three-year prospective followup of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:26–34. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevoo ML, van Gestel AM, van't Hof MA, et al. Remission in a prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Rheumatism Association preliminary remission criteria in relation to the disease activity score. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:1101–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.11.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegert CE, Vleming LJ, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Measurement of disability in Dutch rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 1984;3:305–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02032335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talamo J, Frater A, Gallivan S, et al. Use of the short form 36 (SF36) for health status measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:463–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruynesteyn K, van der Heijde D, Boers M, et al. Determination of the minimal clinically important difference in rheumatoid arthritis joint damage of the Sharp/van der Heijde and Larsen/Scott scoring methods by clinical experts and comparison with the smallest detectable difference. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:913–20. doi: 10.1002/art.10190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molenaar ET, Voskuyl AE, Dinant HJ, et al. Progression of radiologic damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical remission. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:36–42. doi: 10.1002/art.11481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Tuyl LH, Felson DT, Wells G, et al. Evidence for predictive validity of remission on long-term outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:108–17. doi: 10.1002/acr.20021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells GA, Boers M, Shea B, et al. Minimal disease activity for rheumatoid arthritis: a preliminary definition. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:2016–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde DM, et al. Radiographic changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients attaining different disease activity states with methotrexate monotherapy and infliximab plus methotrexate: the impacts of remission and tumour necrosis factor blockade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:823–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, et al. Disconnect between inflammation and joint destruction after treatment with etanercept plus methotrexate: results from the trial of etanercept and methotrexate with radiographic and patient outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3119–25. doi: 10.1002/art.22143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown AK, Conaghan PG, Karim Z, et al. An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2958–67. doi: 10.1002/art.23945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Tuyl LH, Vlad SC, Felson DT, et al. Defining remission in rheumatoid arthritis: results of an initial American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:704–10. doi: 10.1002/art.24392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marzo-Ortega H, Green MJ, Keenan AM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of early intervention with intraarticular corticosteroids followed by sulfasalazine versus conservative treatment in early oligoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:154–60. doi: 10.1002/art.22467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verstappen SM, McCoy MJ, Roberts C, et al. Beneficial effects of a 3-week course of intramuscular glucocorticoid injections in patients with very early inflammatory polyarthritis: results of the STIVEA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:503–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machold KP, Landewe R, Smolen JS, et al. The Stop Arthritis Very Early (SAVE) trial, an international multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on glucocorticoids in very early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:495–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saleem B, Mackie S, Quinn M, et al. Does the use of tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapy in poor prognosis, undifferentiated arthritis prevent progression to rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1178–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emery P, Durez P, Dougados M, et al. Impact of T-cell costimulation modulation in patients with undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis or very early rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and imaging study of abatacept (the ADJUST trial) Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:510–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suarez-Almazor ME, Belseck E, Shea B, et al. Antimalarials for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;4:CD000959. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Visser H, le Cessie S, Vos K, et al. How to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis early: a prediction model for persistent (erosive) arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:357–65. doi: 10.1002/art.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]