Abstract

B-type lamins, the major components of the nuclear lamina, are believed to be essential for cell proliferation and survival. We found that mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) do not need any lamins for self-renewal and pluripotency. Although genome-wide lamin-B binding profiles correlate with reduced gene expression, such binding is not directly required for gene silencing in ESCs or trophectoderm cells. However, B-type lamins are required for proper organogenesis. Defects in spindle orientation in neural progenitor cells and migration of neurons probably cause brain disorganizations found in lamin-B null mice. Thus, our studies not only disprove several prevailing views of lamin-Bs but also establish a foundation for redefining the function of the nuclear lamina in the context of tissue building and homeostasis.

The major structural components of the nuclear lamina found underneath the inner nuclear membrane in metazoan nuclei are type V intermediate filament proteins called lamins (1). Mammals express both A- and B-type lamins encoded by three genes, Lmna, Lmnb1, and Lmnb2. Lmnb1 and Lmnb2 express lamin-B1 and -B2, respectively. Lmnb2 also expresses lamin-B3 through alternative splicing in testes. Mutations in lamins have been linked to a number of human diseases referred to as laminopathies (2), although the disease mechanism remains unclear. A-type lamins are expressed only in a subset of differentiated cells and are not essential for basic cell functions (3, 4). By contrast, at least one B-type lamin is found in any given cell type. Because numerous functions, including transcriptional regulation, DNA replication, and regulation of mitotic spindles, have been assigned to B-type lamins, they are thought to be essential for basic cell proliferation and survival (1, 5–8).

The nuclear lamina can regulate gene silencing by creating a repressive environment or through direct binding of lamins to genes to suppress their expression (9–13). Global mapping of chromatin regions that interact with lamin-B1 indicates that lamin-B1–associated domains generally show low gene expression (14). Moreover, interactions between lamin-B1 and chromatin change after embryonic stem cells (ESCs) differentiate, and increased lamin-B1 binding correlates with silencing of genes, which is important for lineage specification. Thus, B-type lamins have been proposed to be essential for transcriptional silencing during differentiation (15).

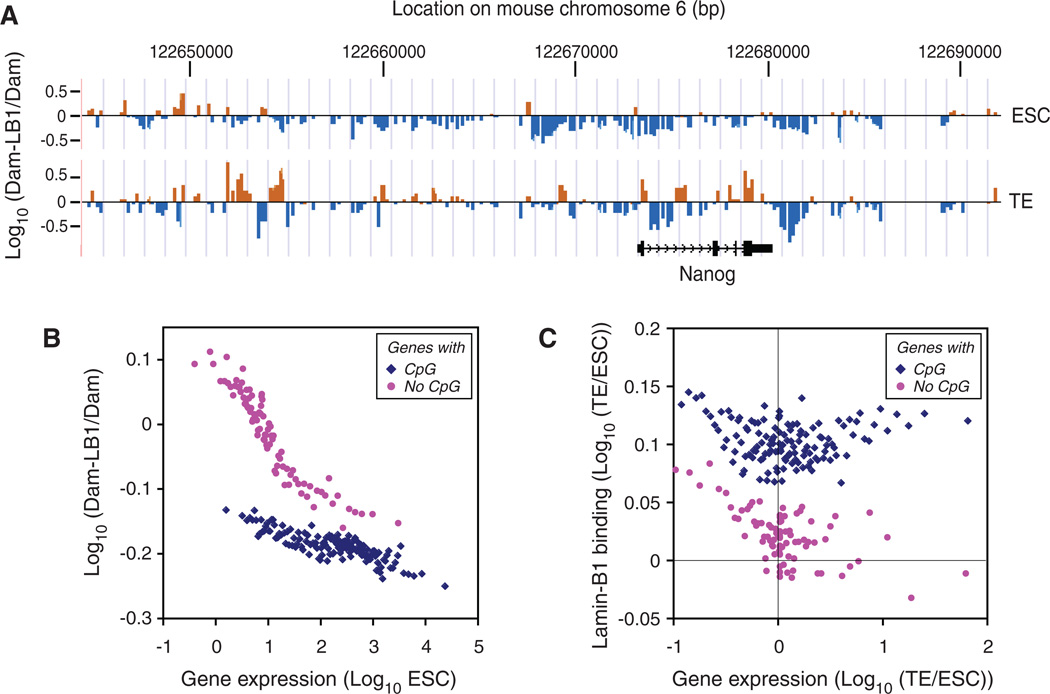

Although B-type lamins are reported to function in seemingly unrelated cellular processes, studies have questioned some of these roles (16–20). Published analyses have been done under conditions in which not all lamin proteins were removed. Thus, definitive tests for the functions of lamins are lacking. To study the role of lamin-B in transcription, we first mapped lamin-B1–chromatin interactions in wild-type ESCs and trophectoderm (TE) cells derived from ESCs by expressing a fusion protein of lamin-B1 with DNA adenine methyltransferase and measuring methylated regions of the genome (Dam-ID analyses) (14).We found that lamin-B1 binding patterns in the ZHBTc4 ESCs (21) that we used were similar to those of other ESCs (15), but differed from those of TE cells, fibroblasts, neural progenitor cells, and astrocytes at both large (15) and fine (0.5 to 2 kb) scales surrounding promoters (figs. S1 to S3 and table S1). Most developmentally controlled genes exhibited increased interaction with lamin-B1 after ESCs differentiated to TE cells (Fig. 1A, fig. S3D, and table S1). Lamin-B1 binding was inversely related to gene expression in ESCs based on the published RNA-seq (22) (Fig. 1B). Interactions of lamin-B1 with promoters of down-regulated genes increased after differentiation of ESCs to TE cells (Fig. 1C, left). Thus, lamin-B binding to promoters correlates with suppressed transcription.

Fig. 1.

Lamin-B1–chromatin interactions and gene silencing in ESCs and TE. (A) Binding of lamin-B1 around the Nanog gene locus as an example of differential lamin-B1 binding to genes in ESCs and TE cells. ZHBTc4 ESCs expressing the tetracycline (Tc)-regulated Oct4 transgene were used for efficient TE differentiation (21).x axis, the positions of individual orange and blue bars at chromosome 6. Each bar is plotted at ~250–base pair (bp) intervals. y axis, lamin-B1 binding plotted as the log10 ratio of methylation values of Dam–lamin-B1 over Dam alone. Orange bars, positive values; blue bars, negative values. (B) Correlation of lamin-B1 binding with low expression of genes with or without CpG islands in ESCs. y axis, the log10 ratio of methylation values of Dam–lamin-B1 over Dam alone; x axis, the log10 gene expression level. (C) Correlation of lamin-B1 binding with decreased gene expression in TE cells relative to ESCs. x axis, the log10 ratio of gene expression in TE to that in ESCs; y axis, the log10 ratio of lamin-B1 binding in TE to that in ESCs. Each dot is the average of 100 genes with similar expression (B) or ratio of expression (C). There was no correlation between DNA methylation of CpG islands and lamin-B1 binding.

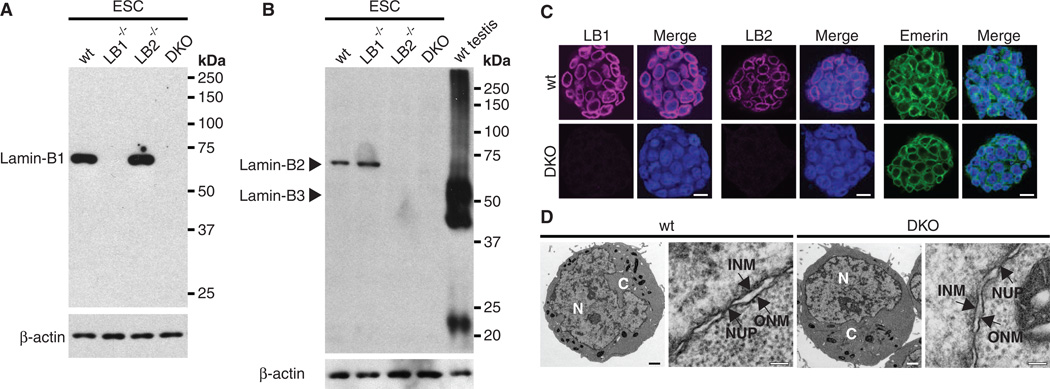

Next, we created Lmnb1 and Lmnb2 knockout mice (fig. S4) and derived ESCs (23) with the following genotypes: Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+, Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+, Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/−, and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− from blastocysts obtained by mating Lmnb1+/−Lmnb2+/− mice. Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− ESCs did not express any lamin-Bs (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S5A). Lamin-A and lamin-C transcripts and proteins were also not detected in all ESCs (fig. S5, A and B). Thus, the Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− ESCs did not express any lamins. Surprisingly, nuclear envelopes and nuclear pores in lamin-null ESCs were indistinguishable from those of controls (Fig. 2, C and D). Although lamin-null ESCs had a slight delay in prometaphase (fig. S6), they expressed pluripotent markers, had colony morphologies (fig. S5, C and D) and growth rates (fig. S7), and maintained euploidy similar to those of controls (table S2). Thus, lamins are not essential for ESCs.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− ESCs. (A and B) Protein immunoblotting analyses of lamin-B1, -B2, and -B3 (B3 shares the same C terminus as B2). Wild-type testes lysates were used as positive controls for lamin-B3. β-Actin was used as a loading control. wt, LB1−/−, LB2−/−, and DKO represent Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+, Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+, Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/−, and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/−, respectively. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of ESCs with antibodies to lamin-B1 (LB1), lamin-B2 (LB2), or emerin. DNA was counterstained with Hoechst dye. Scale bars, 10 µm. (D) Electron micrographs of ESCs. N, nucleus; C, cytoplasm; NUP, nuclear pore; INM, inner nuclear membrane; ONM, outer nuclear membrane. Scale bars, 1 µm (whole-cell views) and 0.1 µm (enlarged views).

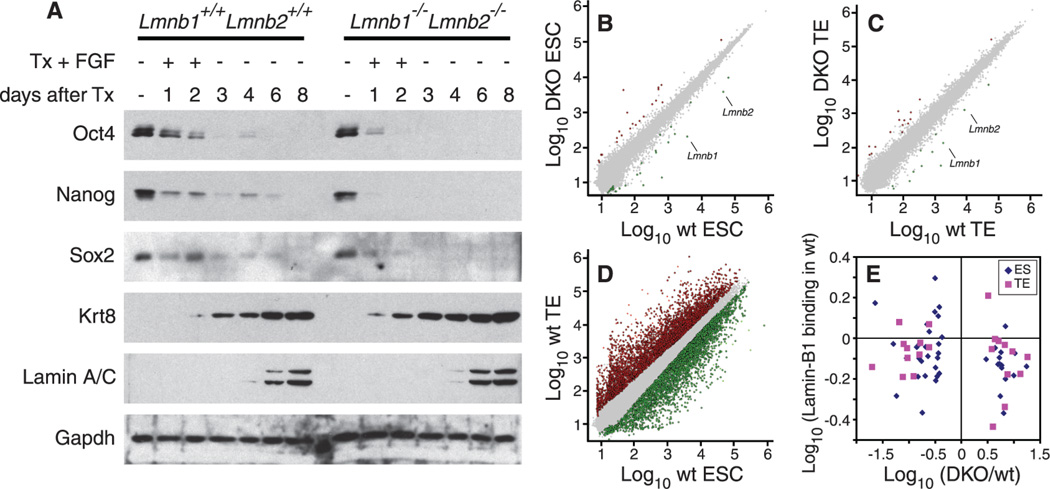

We next induced TE differentiation by expressing tamoxifen-driven Cdx2, a transcription factor required for TE development (24). In the absence of tamoxifen, Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− ESCs expressed similar amounts of pluripotency markers (Fig. 3A). Cdx2 induction by tamoxifen drove TE differentiation in both wild-type and lamin-null ESCs with similar efficiencies as judged by protein or RNA abundance for TE markers (Fig. 3A and fig. S8). Microarray analyses revealed that although deleting B-type lamins resulted in changes of gene expression in ESCs or TE cells, respectively (Fig. 3, B to D, and tables S3 and S4), the changes did not correlate with lamin-B1 binding to promoters of these genes as measured in wild-type cells (Fig. 3E). Because decreased expression of genes promoting pluripotency and increased expression of TE cell-specific genes occurred before the expression of A-type lamins in TE cells (Fig. 3A), A-type lamins were unlikely to compensate for B-type lamins in regulating expression of these genes. Thus, despite the correlation between lamin-B binding and gene silencing, lamin-Bs do not appear to directly regulate expression of their bound genes in ESCs or TE cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of lamins on gene expression. (A) Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− ESCs exhibit similar changes in protein abundance during differentiation toward the TE lineage. ESCs were treated with tamoxifen (Tx) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) for 2 days to induce differentiation followed by terminal differentiation in the absence of FGF and Tx for 6 days. Protein immunoblotting was used to examine ESC proteins associated with pluripotency (Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog), the TE-specific protein (Krt8), and lamin-A and -C. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. (B to D) Microarray analyses. Gene expression was compared between Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− ESCs (B), TE cells (C), and between Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ ESCs and Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ TE cells (D). Increased or decreased transcription (by twofold) is represented by red or green dots, respectively. The Lmnb1 and Lmnb2 genes are indicated in (B) and (C). (E) Ratios of differentially expressed genes between Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− cells (x axis) were plotted against the lamin-B1 binding of these genes measured by Dam-ID in Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ cells (y axis). Each point indicates a single gene that was differentially expressed between Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− cells in (B) or (C).

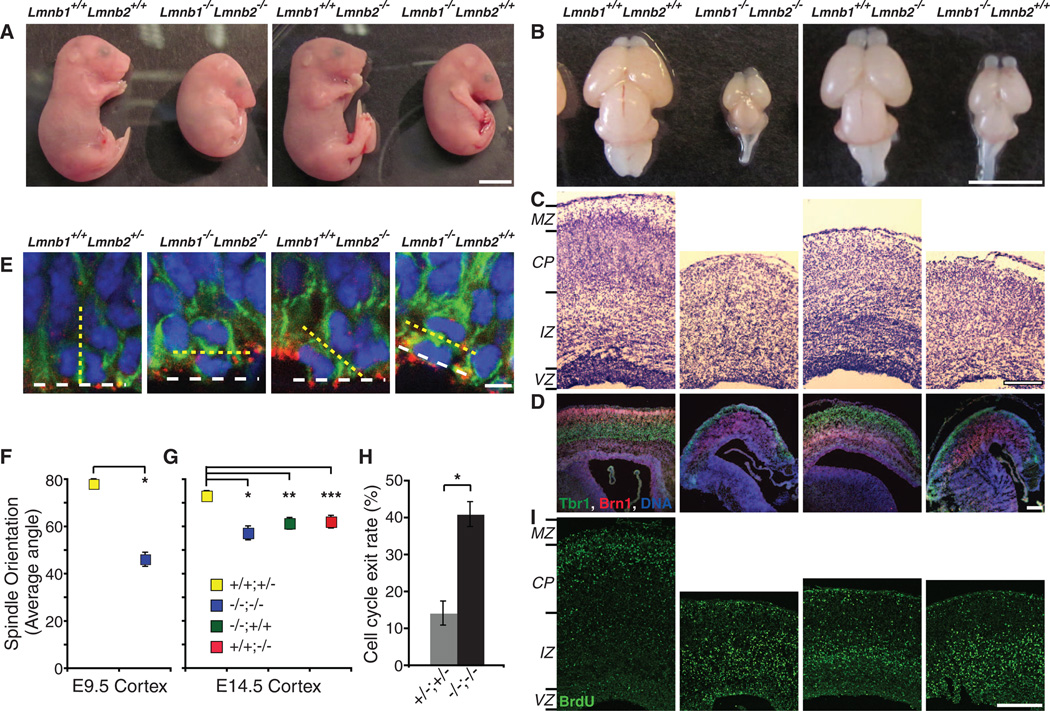

Analyses of progeny from intercrosses of Lmnb1+/−Lmnb2+/− mice at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) and E18.5 revealed Mendelian distribution of all allelic combinations (table S5). Whole-mount histology of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− embryos at E12.5, 15.5, and 18.5 revealed all internal organs as seen in control littermates (fig. S9, A to C). However, body sizes of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+ embryos appeared smaller from E14 to 15, and by E18.5 they were significantly smaller than Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/− and Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ mice (Fig. 4A and fig. S9, B to D). All lamin-B mutant pups were born with heartbeats and paw pinch reflexes, indicating some cardiac and muscular functions, respectively. However, they all failed to breathe and died immediately. The lungs of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+ mice exhibited smaller alveoli compared to those of Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ and Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/− littermates (fig. S10A). The diaphragms were extremely thin with poor phrenic nerve innervations in all lamin-B mutants compared to control littermates (fig. S10, B, C, and E). Both Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− and Lmnb1−/− Lmnb2+/+mice exhibited microcephaly, whereas the brain sizes of Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/− mice were similar to those of control littermates (Fig. 4B and fig. S10D). Thus, lamin-Bs are required for proper development of multiple organs, and defects in lungs, diaphragms, and brains may explain the failure of lamin-B mutant mice to breathe.

Fig. 4.

Requirements for lamin-Bs in brain development. (A) E18.5 embryos. (B to D and I) E18.5 brains with genotypes indicated at the top. (B) E18.5 brains. (C) Nissl staining of coronal sections of the neocortex. MZ, marginal zone; CP, cortical plate; IZ, intermediate zone; VZ, ventricular zone. (D) Layer-specific marker staining of the neocortex. Tbr1 (green) labels early-born deep layer (V and VI) neurons, whereas Brn1 (red) labels late-born outer neuronal layers (II to IV). DNA (blue) was counterstained with Hoechst dye. Three different color channels are merged. Images of individual channels are in fig. S11B. (E) Representative confocal images of mitotic cells at VZ of E14.5 neocortices stained with anti-Pericentrin (red, centrosome), anti-Nestin (green, NPC marker), and Hoechst dye (blue, DNA). Yellow dashed lines indicate the orientation of cleavage planes deduced from positions of anaphase chromosomes and centrosomes, whereas white dashed lines delineate the ventricular surface. (F and G) Quantifications of spindle orientation at E9.5 (F) and E14.5 (G). +/+;+/−, Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/− (E9.5, 78.12 ± 4.49°; E14.5, 73.12 ± 2.17°); −/−;+/+, Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+(E14.5, 61.46 ± 2.51°); +/+;−/−, Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/− (E14.5, 62.17 ± 2.69°); −/−;−/−, Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− (E9.5, 46.25 ± 5.31°; E14.5, 57.39 ± 2.68°). Error bars, SEM. *, P < 10−4, t test (F); *, **, ***, P < 0.002 (G). (H) Cell cycle exit rates. BrdU was injected at E14.5. BrdU+ and Ki67+ cells in neocotices were analyzed 24 hours later (see fig. S18B). Cell cycle exit rates were calculated by dividing the number of BrdU+Ki67− cells (no longer proliferating) by the number of BrdU+Ki67+ cells (still cycling). Error bars, SEM. *, P < 0.001, t test, n = 6 sections (>60 cells per section). (I) BrdU birth dating indicates that neurons from lamin-B mutants have migration defects, whereas neurons from Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/+ littermates have migrated into the basal surface. BrdU (green) was injected at E14.5 to label mid-to-late–born neurons, and mice were dissected at E18.5. Scale bars, 5 mm (A and B), 200 µm (C, D, and I), and 5 µm (E).

At E18.5, the cerebral cortices of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− brains were significantly thinner than those of control littermates (434.42 ± 20.57 versus 711.45 ± 23.76 mm, n = 9 sections for each, SEM; t test, P < 10−6). Cortical layers of brains from all lamin-B mutant mice were disorganized (Fig. 4, C and D, and figs. S11 and S12). Embryonic cerebral cortices lacking A- and B-type lamins did not exhibit large nuclear shape changes (figs. S13 and S14). Analyses of E14.5 cortices with markers for neurons (TuJ1) and subventricular progenitors (Tbr2) or E18.5 cortices with TuJ1 and Nestin (neural progenitors) indicated that the relative position and thickness of neuronal and progenitor cell layers were largely maintained in all lamin-B mutants (fig. S15). Therefore, the disorganization of cortical layers was not simply due to the lack of neuronal differentiation or abnormal expansion of progenitor cells.

Because lamin-B interacts with NudEL (7), a regulator of dynein known to function in spindle orientation, interkinetic nuclear migration (INM), and neuronal migration (25), we tested whether lamin-B is required for these cell functions. Cell cleavage planes in the neural progenitor cells (NPCs) of all lamin-B mutants were significantly more horizontal to the apical surface than those of Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2+/− mice (Fig. 4, E to G). Therefore, both lamin-B1 and -B2 are required for proper orientation of mitotic spindles in NPCs. At E18.5, an increased number of NPCs, as judged by marker staining, were scattered into basal layers in Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− (fig. S16), and at E14.5,G2/MphaseNPCs, as indicated by phospho-histone-H3 label, were also present in more basal positions in Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− compared to controls (fig. S17). This ectopic localization of NPCs may contribute to the enhanced cell cycle exit rates observed (Fig. 4H and fig. S18A) despite the normal cell cycle length (fig. S18B). It also suggested that the nuclei of NPCs failed to undergo INM to the apical surface. Because NPCs of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+and Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/− mice had normal localizations (figs. S16 and S17), lamin-Bs may have redundant functions in INM.

To study neuronal migration, we labeled neurons born at E14.5 with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and analyzed their localization at E18.5. The BrdU+ neurons remained largely near the ventricular or subventricular zones (VZ/SVZ) in all lamin-B mutant brains, whereas in control brains, the BrdU+ neurons moved away from the VZ/SVZ where they were born (Fig. 4I). The BrdU+ neurons in Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/− mice migrated farther away from VZ/SVZ than those of Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− and Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+mice (Fig. 4I). Thus, lamin-B1 has a larger role in neuronal migration than lamin-B2, which could explain why Lmnb1−/−Lmnb2−/− andLmnb1−/−Lmnb2+/+mice exhibited increased apoptosis in neocortices (fig. S19) and decreased brain and body sizes than those of Lmnb1+/+Lmnb2−/−mice (Fig. 4, A and B).

The surprising lack of a requirement for lamins in ESCs and during ESC differentiation in vitro could reflect the nonengagement of these cells in tissue building and thus their lack of a need for spindle orientation and cell migration. The cellular functions of lamin-Bs we uncovered here suggest that lamin-Bs have evolved to facilitate the integration of different cell types into the highly elaborate tissue architectures found in animals. Lamin-B directly binds to NudEL to regulate spindles in vitro (5–7), yet the physiological relevance of this mitotic role has remained unclear. Our findings support both the function of lamin-Bs in dynein-mediated spindle orientation in mitotic NPCs and the role of lamin-Bs in dynein-mediated neuronal migration and INM. By refuting several well-accepted functions of lamin-Bs, this work has set the stage to dissect the mechanism by which the nuclear lamina promotes tissue organization and functions.

Note added in proof: While this work was in review, a role of lamin-B1 and -B2 in brain development has been described byC. Coffinier et al. (26).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Van Steensel and H. Niwa for reagents, M. Sepanski for electron microscopy, O. Martin for technical support, C. Liu (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) for mouse targeting, and the members of the Zheng lab for critical comments. Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of National Institute on Aging (A.A.S. and M.S.H.K.) and R01 GM056312 (Y.Z.). Y.Z. is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. A patent (7510850) regarding the use of Xenopus egg extracts to isolate and study the lamin-B spindle matrix is held by The Carnegie Institution for Science.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1211222/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S19

Tables S1 to S7

References (27–35)

References and Notes

- 1.Dechat T, et al. Genes Dev. 2008;22:832. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen TV, Stewart CL. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2008;84:351. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart C, Burke B. Cell. 1987;51:383. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Röber RA, Weber K, Osborn M. Development. 1989;105:365. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai MY, et al. Science. 2006;311:1887. doi: 10.1126/science.1122771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma L, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:247. doi: 10.1038/ncb1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman B, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:35238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.140749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumaran RI, Spector DL. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlan LE, et al. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanctôt C, Cheutin T, Cremer M, Cavalli G, Cremer T. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:104. doi: 10.1038/nrg2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kind J, van Steensel B. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:320. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Nature. 2008;452:243. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guelen L, et al. Nature. 2008;453:948. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peric-Hupkes D, et al. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:603. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, et al. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:3937. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osouda S, et al. Dev. Biol. 2005;284:219. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang SH, et al. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:3537. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vergnes L, Péterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:10428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffinier C, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:5076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908790107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:372. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cloonan N, et al. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:613. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols J, Silva J, Roode M, Smith A. Development. 2009;136:3215. doi: 10.1242/dev.038893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niwa H, et al. Cell. 2005;123:917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada M, Hirotsune S, Wynshaw-Boris A. Cell Adh. Migr. 2010;4:180. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.2.10715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coffinier C, et al. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:4683. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.