Abstract

The present study addressed the hypothesis that emotional stimuli relevant to survival or reproduction (biologically emotional stimuli) automatically affect cognitive processing (e.g., attention; memory), while those relevant to social life (socially emotional stimuli) require elaborative processing to modulate attention and memory. Results of our behavioral studies showed that: a) biologically emotional images hold attention more strongly than socially emotional images, b) memory for biologically emotional images was enhanced even with limited cognitive resources, but c) memory for socially emotional images was enhanced only when people had sufficient cognitive resources at encoding. Neither images’ subjective arousal nor their valence modulated these patterns. A subsequent functional magnetic resonance imaging study revealed that biologically emotional images induced stronger activity in visual cortex and greater functional connectivity between amygdala and visual cortex than did socially emotional images. These results suggest that the interconnection between the amygdala and visual cortex supports enhanced attention allocation to biological stimuli. In contrast, socially emotional images evoked greater activity in medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and yielded stronger functional connectivity between amygdala and MPFC than biological images. Thus, it appears that emotional processing of social stimuli involves elaborative processing requiring frontal lobe activity.

Keywords: social emotion, biological emotion, attention, memory encoding, amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, fMRI

Emotion has a major impact on cognitive processing (see Dolan, 2002 for a review). To understand these effects, researchers have focused on two orthogonal dimensions of emotion (Anderson, Christoff, Stappen, et al., 2003; Russell & Carroll, 1999): arousal (how exciting or calming) and valence (how positive and negative). Studies based on this two-dimensional approach demonstrate the importance of both arousal and valence.

In terms of valence, positive and negative emotions differ in how they affect various kinds of cognitive processing: memory encoding (Kensinger, 2009; Mather & Carstensen, 2005; Mickley & Kensinger, 2008; Ochsner, 2000; Talmi, Schimmack, Paterson, & Moscovitch, 2007), the scope of attention (Fenske & Eastwood, 2003; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Rowe, Hirsh, & Anderson, 2007), cognitive flexibility (Isen & Daubman, 1984; Isen, Johnson, Mertz, & Robinson, 1985), creative problem solving (Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, 1987; Subramaniam, Kounios, Parrish, & Jung-Beeman, 2009), cognitive control (Dreisbach, 2006), knowledge retrieval (Bäum & Kuhbandner, 2007), and perceptual processing (Kuhbandner, et al., 2009).

Arousal also has effects on memory and other aspects of cognitive processing. People have enhanced memory for emotionally arousing materials (Bradley, Greenwald, Petry, & Lang, 1992; Dolcos & Denkova, 2008; Dolcos, LaBar, & Cabeza, 2004; Hamann, Ely, Grafton, & Kilts, 1999; Kensinger & Corkin, 2004) and their intrinsic features (D’Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004; Doerksen & Shimamura, 2001; Kensinger & Corkin, 2003a; Mather, 2007; Mather & Nesmith, 2008; Nashiro & Mather, in press), but arousal either does not enhance or impair memory information peripheral to the emotional aspect of an event (Kensinger, 2009; Kensinger, Garoff-Eaton, & Schacter, 2007; Mather, Gorlick, & Nesmith, 2009; Payne, Stickgold, Swanberg, & Kensinger, 2008). Highly arousing stimuli also recruit attention (Anderson, 2005; Schimmack, 2005), which interrupts cognitive processing of competing less-salient stimuli (Arnell, Killman, & Fijavz, 2007; Dolcos & McCarthy, 2006; Ihssen, Heim, & Keil, 2007; Ihssen & Keil, 2009; Keil & Ihssen, 2004; Mather, et al., 2006; K. J. Mitchell, Mather, Johnson, Raye, & Greene, 2006; Most, Chun, Widders, & Zald, 2005). In general, emotional arousal modulates cognitive processing, enhancing processing of salient stimuli while reducing processing of non-salient stimuli (Mather & Sutherland, 2011; Sutherland & Mather, under review).

Although this two-dimensional approach can account for many effects, arousal and valence may not be sufficient to explain all of the effects of emotion on cognition. One possibly important factor which past studies have not addressed well is the motivational relevance (see Larson & Steuer, 2009 for related arguments). Emotional reactions are often induced by stimuli related to primary motives, such as survival (e.g., foods; Lang, et al., 1998; Morris & Dolan, 2001) and reproduction (e.g., sexual images; Hamann, Herman, Nolan, & Wallen, 2004). However, people can also feel emotions when they encounter social stimuli that are not directly related to survival or reproduction (e.g., Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; Singer, et al., 2004). These two kinds of emotional stimuli might influence cognitive processing in different ways.

For example, many studies on the effects of emotion on cognition have used picture stimuli obtained from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS: Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1997). The IAPS involves arousing pictures depicting sexual behaviors, severe injuries, dead bodies, or aimed guns. These stimuli are highly related to survival or reproduction, representing situations that imply direct physical outcomes (either positive or negative), such as death, injuries, and sexual experiences. In contrast, other pictures in the IAPS are less relevant to survival or reproduction and are more relevant to social life (e.g., smiling children, crying people). These stimuli represent social situations with other individuals, each of whom could have a different intention, goal, or emotional feeling, depending on the contexts and other individuals. Because of the complex nature of social situations, the meanings, outcomes and causes of emotion are embedded in each stimulus context.

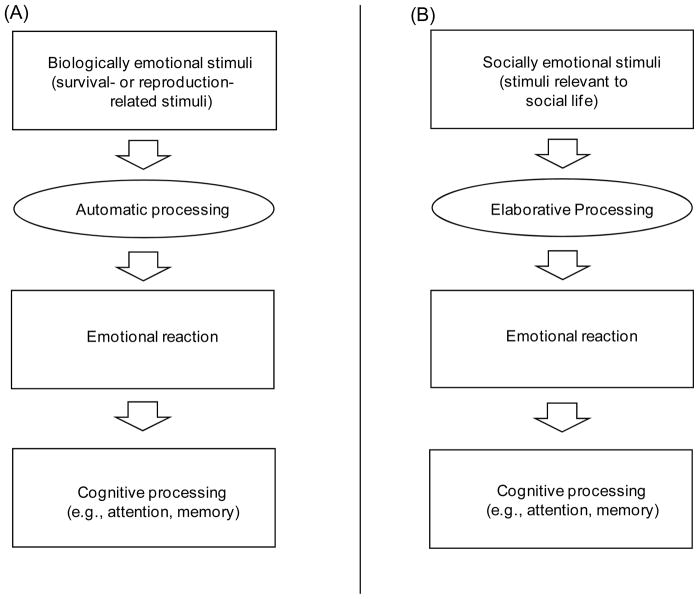

These considerations suggest the following hypothesis: Emotional materials related to survival/reproduction (biologically emotional materials) imply clear meanings and direct physical outcomes, and therefore, their emotional nature can be detected even with just automatic processing (see Figure 1A). In contrast, emotional materials less related to survival or reproduction and more strongly related to social life (socially emotional materials) have ambiguous meanings and outcomes shaped by their context. Therefore, they need to be interpreted by each individual in each context in order to elicit an emotion. Thus, socially emotional materials should require effortful cognitive processing to elicit emotions and any subsequent effects of emotion on cognition (see Figure 1B). The present study aims to address this hypothesis.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms by which biologically and socially emotional stimuli modulate cognitive processing. (A) Biologically emotional stimuli imply clear/direct physical outcomes. Therefore, their emotional nature can be detected even with just automatic processing, and they can modulate cognitive processing without elaborative processing. (B) In contrast, socially emotional stimuli have ambiguous meanings and outcomes. Thus, each social stimulus has to be interpreted by each individual in each context in order to elicit an emotion and to modulate cognitive processing.

Effects of Survival or Reproduction Relevance

Consistent with the hypothesis, past studies reported preferential processing of survival-relevant stimuli. People tend to detect threats to survival (such as a gun or snake) more automatically than other neutral stimuli (e.g., Blanchette, 2006; Brosch & Sharma, 2005; Carlson, Fee, & Reinke, 2009; Fox, Griggs, & Mouchlianitis, 2007; Öhman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001). Similar tendencies were reported in preschool children (LoBue & DeLoache, 2008) and infants from 5 to 18 month olds (DeLoache & LoBue, 2009; LoBue & DeLoache, 2008, 2010; Rakison & Derringer, 2008), suggesting the possibility that humans have an innate predisposition to process survival-related stimuli preferentially.

Although past research has mostly focused on the effects of threatening stimuli, recent research demonstrated that the effects of survival relevance are not limited to negative stimuli. Positive stimuli related to reproduction, such as sexual materials (Lykins, Meana, & Kambe, 2006) and babies’ faces (Brosch, Sander, Pourtois, & Scherer, 2008; Brosch, Sander, & Scherer, 2007), captured people’s attention automatically. Likewise, infants’ faces more quickly induced strong activity in reward-related regions in the brain than did adults’ faces (Kringelbach, et al., 2008; Nitschke, et al., 2004). There is also evidence that basic motives, such as hunger or thirst, produce preferential processing of positive reinforcers that satisfy those needs (Drobes, et al., 2001; Mogg, Bradley, Hyare, & Lee, 1998; Morris & Dolan, 2001). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated preferential attention and memory encoding for taboo words compared to other emotional words (Anderson, 2005; Jay, Caldwell-Harris, & King, 2008; Kensinger & Corkin, 2003b; MacKay, et al., 2004; Mathewson, Arnell, & Mansfield, 2008). Although taboo words are defined by social norms, many of them refer to sexual acts or body products (Foote & Woodward, 1973; Jay, 2009). Thus, it appears that people can process survival/reproduction-related stimuli preferentially even after they are converted to an abstract/verbal format.

In summary, past studies suggest that materials related to survival or reproduction receive preferential processing. Most of these studies, however, did not compare survival relevance with social life relevance. Thus, it is unclear whether survival relevance impacts cognitive processing more automatically than social relevance.

Social Cognitive Neuroscience Studies on Biological vs. Social Emotions

Recent studies in social cognitive neuroscience have started to examine how biological and social emotions are processed in the brain (Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004; Eisenberger, et al., 2003; Immordino-Yang, McColl, Damasio, & Damasio, 2009; Jackson, Meltzoff, & Decety, 2005; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Bramati, & Grafman, 2002; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002; Moll, Eslinger, & Oliveira-Souza, 2001; Singer, et al., 2004). Although each study dealt with a different aspect of social emotion, such as social pain, moral judgments, empathy, or compassion, they each suggested differences in underlying processing between biologically and socially emotional stimuli.

For example, observing others’ physical pain induced earlier activity in emotion-related regions in the brain than did observing others’ social pain (Immordino-Yang, et al., 2009). Studies also revealed that biologically emotional images (e.g., sexual images or mutilation) modulate activity in visual cortex (Bradley, et al., 2003), skin conductance response, and startle reflex (Bradley, Codispoti, Cuthbert, & Lang, 2001) more strongly than do socially emotional images (e.g., happy families). In addition, processing of biologically emotional films (i.e., a pizza commercial; wounded bodies) produced greater activity in brain regions involved in visceral responses (Britton, et al., 2006), while processing of socially emotional stimuli (e.g., comedy show; poignant bereavement scene; pictures involving people or faces) has been associated with cortical regions that implement higher order cognitive processing (Britton, et al., 2006; Norris, Chen, Zhu, Small, & Cacioppo, 2004). These results seem consistent with our hypothesis, suggesting that people process the emotional implications of biologically emotional stimuli automatically, but engage in more elaborative processing when presented with socially emotional stimuli.

Since these studies targeted physical or neural responses induced by biological and social emotional stimuli, however, it is not clear whether relevance to survival or reproduction versus relevance to social life affect cognitive processing (e.g., attention or memory encoding) differently. In addition, there has been no clear agreement about how to define biologically and socially emotional stimuli, leading different studies to use different ways to categorize biologically and socially emotional stimuli. Furthermore, most of the past studies did not match arousal and valence between social vs. biological emotional materials. Thus, it is unclear whether the results were due to the social/biological nature of stimuli or arousal/valence.

Overview of the Present Study

We tested our hypothesis that, compared with socially emotional stimuli, biologically emotional materials impact cognitive processing more automatically using several different paradigms. In Study 1, we compared the effects of biological versus social emotional materials on attention and memory encoding. In Study 2, we further examined memory encoding of biological and social emotional materials, manipulating cognitive resources available at encoding to see if cognitive resources affect memory encoding of biologically and socially emotional materials differently. Finally, in Study 3 we investigated the brain regions associated with processing biological and social emotional stimuli by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Given the absence of clear definitions about biological and social emotional materials in the literature, across all studies, we adopted a bottom-up approach to define biologically and socially emotional stimuli to reduce any arbitrary biases introduced by the researchers. That is, we selected stimuli based on people’s ratings on relevance to survival/reproduction and relevance to social life. Although there might be emotional stimuli rated high in relation to survival/reproduction and to social adaptation, the primary purpose of the current study is to identify the effects of biological and social relevance separately. Therefore, as biologically emotional stimuli, we used stimuli rated high in relation to survival/reproduction and low in relation to social life. Socially emotional stimuli were also defined as those rated high in relation to social life but low in relation to survival/reproduction. We also carefully matched arousal and valence across the biologically and the socially emotional stimuli to avoid confounding the stimulus type (i.e., biological or social stimuli) and arousal or valence.

Study 1

In Study 1, we examined the effects of biologically/socially emotional stimuli on attention. Previous studies revealed that emotional stimuli have more impact on attention disengagement than on attention capture (Fox, Russo, Bowles, & Dutton, 2001; Fox, Russo, & Dutton, 2002) especially when they compete with other stimuli for attention (Anderson, 2005; Buodo, Sarlo, & Palomba, 2002; Pratto & John, 1991; Schimmack, 2005). Based on these findings, we investigated the effects of biologically and socially emotional stimuli on attention disengagement, by using a dot-probe task combined with other competing stimuli. To enhance participants’ engagement, a problem solving task was employed as a competing task (see Schimmack, 2005 for a similar procedure).

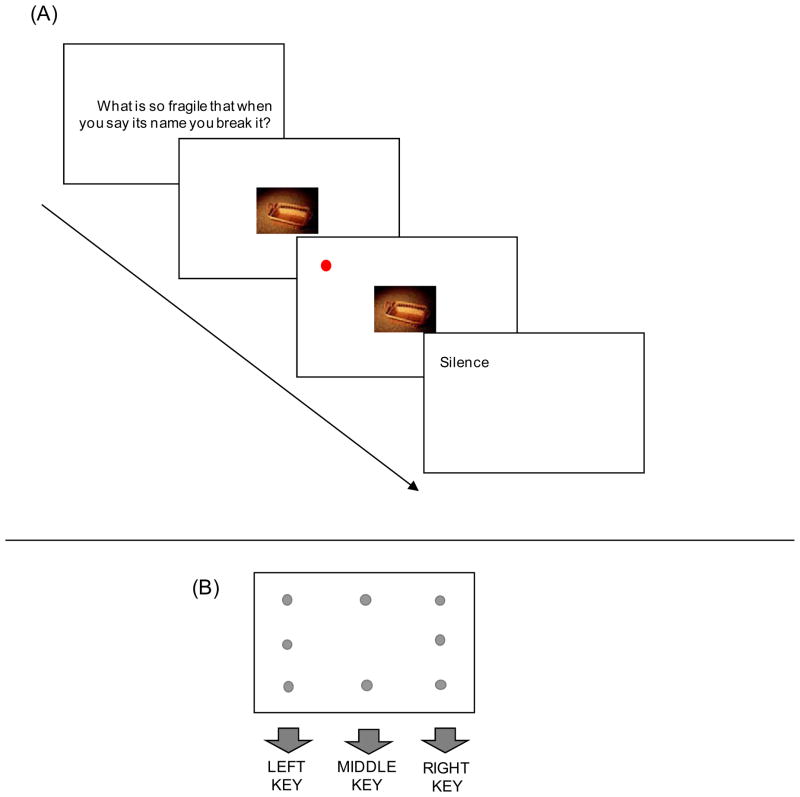

On each trial (Figure 2A), participants were shown a riddle, which was followed by either a biological, social, neutral picture, or asterisks at the center of a display. After 150 ms of the picture or the asterisks, participants saw a dot-probe at one of eight possible locations (Figure 2B), all of which were different from the picture’s location. The participants’ task was to indicate the location of the dot-probe as quickly and as accurately as possible. If participants have more difficulty disengaging their attention from biologically emotional pictures than from socially emotional ones, their reaction times to detect the dot-probe should be slower after biological pictures than social ones. Study 1 also included a surprise memory test of pictures to examine the effects of biologically/socially emotional stimuli on memory as well as attention.

Figure 2.

(A) A schematic representation of procedures in Study 1. On each trial, participants viewed a riddle and then saw a picture (in the biological, social, and neutral conditions) or asterisks (in the control condition). After 150 ms of the picture or the asterisks (150 ms), the red dot appeared at one of eight possible locations. Participants were asked to indicate the location of the dot as quickly and as accurately as possible. Immediately after they answered the correct location of the dot, the dot was replaced by the solution to the riddle. (B) Eight possible locations for the dot probe and the correct key response for each of them.

Method

Participants

Twenty-two Japanese undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Tokyo took part in the experiment (14 males; Mage = 21.09, SD = 2.36).

Materials: Pictures

Based on pilot ratings (see Supplementary Materials), we selected 10 biological (5 positive, 5 negative), 10 social (5 positive, 5 negative), and 10 neutral pictures. Biological and social pictures were matched in arousal and valence (see S-Table 1). Examples for each category were sexual images or appetizing food for biological positive pictures; a snake, skull, or a man who commits suicide for biological negative ones; smiling people, celebrating athletes, or money for social positive ones; KKK or neo-Nazi for social negative ones. The recognition test included an additional 5 biological positive, 5 biological negative, 5 social positive, 5 social negative, and 10 neutral pictures as foils.

Procedure

We employed a modified version of the dot-probe task to examine the effects of biological and social emotional stimuli on attention (Figure 2; see Supplementary Methods for details). After participants finished the attention task, they worked on a mathematical calculation task for 5 min, which was followed by a surprise recognition test for the pictures. In the memory test, participants were shown pictures used in the attention task and new pictures and asked to indicate whether they saw each picture or not.

Results

Effects of pictures on reaction time to detect the dot-probe

In this and the following studies in the current article, outlier response times were identified using Tukey (1977)’s criterion of three times the interquartile range (the hinge-spread) higher than the third quartile in each condition. The remaining reaction times were submitted to a one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA).1 This ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of stimulus type, F(3, 63) = 7.74, R2 = .01, p < .01. Post-hoc comparisons (Tukey’s HSD) revealed that reaction times were significantly longer after biological pictures than after social pictures, neutral pictures, or asterisks (Figure 3A), respective ts(63) = 2.78, 3.30, 4.44, SEs = 10, ps < .05. In contrast, the reaction time did not differ across social, neutral, and control conditions (ps > .30). In addition, the difference between biological and social pictures was not modulated by valence and arousal (Figure 3B; see Supplementary Results for details). These results suggest that people have more difficulty disengaging their attention from biologically emotional pictures than from socially emotional pictures, regardless of valence and subjective arousal.

Figure 3.

Effects of stimulus type (biologically vs. socially emotional stimuli) on attention in Study 1. Error bars represent standard errors. (A) Reaction times to detect the dot-probe were slower after biologically emotional pictures than other conditions, while the reaction times did not differ across social, neutral and control conditions. (B) The valence category and subjective arousal did not modulate the results in reaction times.

Memory of pictures

Next, we examined participants’ memory for biologically versus socially emotional pictures. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA on the hit rates of pictures revealed a significant effect of picture type, F(2, 42) = 8.77, R2 = .19, p < .01. Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests revealed that participants remembered biological (M = .33) and social pictures (M = .39) significantly better than neutral ones (M = .19), respective ts(42) = 3.13, 4.15, SEs = .05, ps < .05. There was no significant difference for biological and social pictures (p > .40). Further analyses revealed no significant effects of valence and arousal (see Supplementary Results).2

Discussion

Study 1 revealed that biologically emotional stimuli hold attention more than do socially emotional stimuli, regardless of valence and arousal. Like the biologically emotional pictures, socially emotional pictures had higher arousal than neutral pictures—yet the social pictures did not slow reaction times more than neutral pictures did. Thus, the relevance to survival or reproduction had a larger impact on attention than arousal or valence. In contrast, participants remembered both biologically and socially emotional stimuli significantly better than neutral stimuli. In fact, they remembered socially emotional stimuli as well as biologically emotional stimuli. These results suggest that memory for socially emotional stimuli and memory for biologically emotional stimuli are facilitated through different mechanisms. Study 2 addresses this possibility.

One possible concern about Study 1 is that each person might have different evaluations about what is related to social adaptation and what is related to survival/reproduction, depending on his/her experiences. In addition, Study 1 might not have enough statistical power to detect the effects of arousal and valence, because of the relatively small number of trials in each condition. The statistical power issue was exacerbated by the fact that dichotomization of continuous variables (i.e., arousal and valence in this case) results in the loss of the statistical power (Irwin & McClelland, 2003). However, in a supplemental study (S-Study 1; see Supplementary Studies for details), we replicated the results from Study 1 while determining each picture’s biological/social relevance, arousal, and valence by each participant’s evaluation. In this supplemental study, we treated arousal and valence as continuous variables to increase the statistical power; as in Study 1 we found a significant effect of biological relevance but not of valence and arousal (S-Figure 1). Thus, this supplemental study provides additional support for the importance of biological relevance in attention.

Study 2

Past research suggests two different mechanisms by which emotion enhances memory (Anderson, Christoff, Panitz, De Rosa, & Gabrieli, 2003; Kensinger & Corkin, 2004; Talmi, et al., 2007); a) emotional materials tend to attract and hold attention more automatically than do neutral materials, and b) emotional materials recruit more effortful semantic elaboration than neutral materials. In Study 1, we found that biologically emotional stimuli held attention more strongly than socially emotional ones when the pictures were not relevant to the primary task. This automatic capture of attention by biologically emotional stimuli but not socially emotional stimuli suggests that memory for biologically emotional stimuli would depend on the automatic attention mechanism more than would socially emotional stimuli. In contrast, if each socially emotional stimulus has to be interpreted by each individual in each context to elicit an emotion (as we posited above), the semantic elaborative process should be more crucial in memory for socially emotional stimuli than for biological stimuli. Study 2 addressed these predictions.

Half of the participants in Study 2 viewed emotional or neutral pictures while working on a secondary task (divided-attention condition), whereas the other half viewed pictures without any additional task (full-attention condition). This encoding session was followed by a surprise recognition test of picture memory. To examine how vividly participants remembered each picture, we included remember-know judgments (Gardiner, Ramponi, & Richardson-Klavehn, 1998) as well as old-new judgments. If memory encoding of socially emotional materials depends on effortful elaborative processing, participants should show worse memory for social stimuli in the divided-attention condition than in the full-attention condition. In contrast, if memory for biologically emotional materials is enhanced through automatic attention mechanisms, participants’ memory for biologically emotional pictures should be less influenced by the attention manipulations than their memory for socially emotional stimuli.

Method

Participants

Forty-eight Japanese undergraduates and graduate students at University of Tokyo participated (21 males; Mage = 22.19, SD = 2.03). They were randomly assigned to either full- (N = 25) or divided-attention condition (N = 23). Data from two participants were not used; one did not understand the differences between remember/know and old/new judgments in the recognition test, and the other did not press keys during the encoding session.

Materials

Based on the pilot picture rating study, we chose 32 biological (16 positive, 16 negative), 32 social (16 positive, 16 negative), and 32 neutral pictures. Biologically and socially emotional pictures were selected to have matched valence and arousal levels (see S-Table 1). In the recognition task, 78 non-studied foils (13 biological positive, 13 biological negative, 13 social positive, 13 social negative, and 26 neutral) were used.

Procedure

Participants saw each of 96 pictures for 2500 ms in a randomized order with a 4-sec inter-trial interval. The encoding session consisted of four blocks. Both in the full- and divided-attention conditions, participants were asked to make a judgment about whether they liked or disliked each picture as quickly and as accurately as possible, using their right hand to press keys.

In addition to this picture judgment task, participants in the divided attention condition listened to a sound sequence, and worked on a sound-pitch judgment task (Gilbert & Silvera, 1996) throughout the session. The sound sequence consisted of a low-pitched, a medium-pitched, and a high-pitched tone in randomized order with variable intervals (approx 1 – 3 secs). Participants’ task was to keep track of the sound sequence and to press a button with their left hand immediately after they detected a specific sequence of three tones: low, medium, and high pitched tones in that order regardless of interval duration.

The encoding session was followed by a mathematical calculation task for three minutes. Finally, participants were given a surprise recognition test for the pictures. They indicated whether they remembered seeing the picture (i.e., old) or not (i.e., new). For any item that received an “old” decision, participants were asked to indicate whether they vividly remembered seeing the picture in the first session (i.e., remember) or sensed that the picture was familiar but did not remember any details about its prior presentation (i.e., know).

Results

Effects of attention and stimulus type on memory

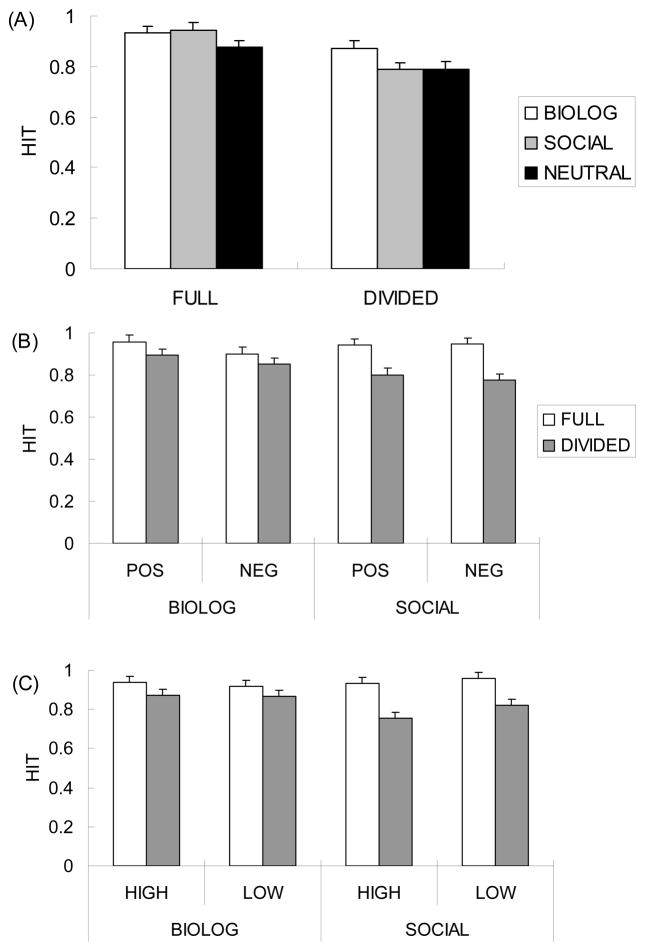

A 2 (attention: full vs. divided) × 3 (stimulus type: biological, social vs. neutral) ANOVA on the hit rate3 revealed significant effects of attention, F(1, 44) = 9.66, p < .01, R2 = .18, stimulus type, F(2, 88) = 5.53, p < .01, R2 = .33, and an interaction between attention and stimulus type, F(2, 88) = 3.36, p < .05, R2 = .17. The attention manipulation had a significant effect for social, F(1, 88) = 16.08, p < .01, and neutral stimuli, F(1, 88) = 4.31, p < .05, but not for biological stimuli (p > .10; Figure 4A). Participants in the full-attention condition remembered biological and social stimuli significantly better than neutral stimuli, ts(44) = 3.16, 3.94, SEs = .02, ps < .01, with no significant difference between biological and social stimuli (p > .60; Tukey’s HSD). In contrast, participants in the divided-attention condition remembered biological stimuli better than social, t(44) = 2.39, SE = .04, p < .05, and neutral stimuli, t(44) = 2.21, SE = .04, p < .05, and there was no significant difference between social and neutral stimuli (p > .95).4 These results suggest that cognitive resources contribute more to encoding socially emotional materials than to encoding biologically emotional materials.

Figure 4.

Results of the hit rates from the picture memory test in Study 2. Error bars represent standard errors. (A)When people have enough cognitive resources at encoding, they remembered both biologically and socially emotional stimuli better than neutral stimuli. In contrast, when participants’ attention was focused elsewhere, it impaired their memory for social stimuli, but not for biological stimuli. (B) Valence and (C) subjective arousal did not modulate the patterns.

Effects of attention and stimulus type on Remember rates

A similar analysis on the proportion of “Remember” responses also revealed significant effects of attention, F(1, 44) = 5.75, p < .05, R2 = .10, of stimulus type, F(2, 88) = 8.28, p < .01, R2 = .22, and an interaction between them, F(2, 88) = 5.27, p < .01, R2 = .10. The attention manipulation had a significant effect on memory for social and neutral stimuli, Fs(1, 88) =11.35, 4.33, ps < .05, but not for biological stimuli (p > .30; Figure 5A). Participants in the full-attention condition were more likely to vividly remember social stimuli than biological or neutral stimuli, ts(44) = 3.35, 4.53, SEs = .02, .03, ps < .01, while there was no significant difference between biological and neutral stimuli (p > .20; Tukey’s HSD). When participants’ attention was focused elsewhere in the divided-attention condition, however, they did not show enhanced remember rates for social stimuli compared with neutral or biological stimuli (ps > .20). Instead, they produced a greater proportion of remember responses to biological stimuli than to neutral stimuli, t(44) = 3.16, SE = .03, p < .05. Thus, it appears that vivid memory for socially emotional stimuli depends more on cognitive resources than does vivid memory for biologically emotional stimuli.5

Figure 5.

Results of the Remember rates from the picture memory test in Study 2. Error bars represent standard errors. (A) Attentional resources influenced encoding detailed memories for socially emotional stimuli more than for biologically emotional stimuli; although social stimuli produced higher remember rates than biological stimuli in the full attention condition, dividing attention impaired memory for socially emotional stimuli, but not for biologically emotional stimuli. Similar results were obtained regardless of (B) valence and (C) subjective arousal.

Like/Dislike Judgments in the Encoding Session

To examine whether the attention manipulation influenced like/dislike judgments during the encoding session, the reaction times of like/dislike judgment were submitted to a 3 (stimulus type) × 2 (attention) ANOVA. This ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of stimulus type, F(2, 88) = 26.24, p < .01, R2 = .02, with no other significant effects (ps > .30). Participants took longer to make judgments about neutral pictures (M = 1178 ms) than social (M = 1092 ms) and biological pictures (M = 1048 ms; Tukey’s HSD), ts(88) = 4.12, 7.12, SEs = 18, ps < .01. This result is not surprising because we did not allow participants to judge pictures as neutral in their like/dislike judgments. More interestingly, participants took longer to make a decision about social pictures than biological pictures (Msocial = 1092 ms vs. Mbio = 1048 ms), t(88) = 2.40, SE = 18, p < .05, suggesting that socially emotional stimuli require deeper cognitive processing to make like/dislike judgments than do biologically emotional stimuli.

We also calculated the proportion of pictures for which the participant’s judgments were consistent with the valence categories (i.e., liked positive pictures and disliked negative pictures), to examine the accuracy of participants’ judgments. This consistency measure was submitted to a 2 (attention) × 2 (stimulus type: social vs. biological) ANOVA. Because it is hard to define correct judgments for neutral pictures, we did not involve neutral pictures in this analysis. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of stimulus type, F(1, 44) = 4.20, p < .05, R2 = .06, indicating that participants were more accurate when they made judgments about biological pictures than social ones (Mbio = .76 vs. Msocial = .72). None of the other effects were significant (ps > .20).

Discussion

When participants had enough attention (i.e., full attention condition), socially emotional stimuli were remembered as well as biologically emotional stimuli. In addition, when we looked at remember rates, socially emotional stimuli produced even higher remember rates than biological stimuli. However, dividing attention impaired memory for socially emotional stimuli more than for biologically emotional stimuli. As a result, in the divided attention condition, biologically emotional stimuli were more likely to be recognized than socially emotional stimuli. Further analyses confirmed similar patterns irrespective of valence and arousal (Figure 4B–4C; Figure 5B–5C; see Supplementary Results for details). These results suggest that memory for socially emotional stimuli is enhanced through effortful elaboration, while memory for biologically emotional stimuli is enhanced through automatic attention allocation, regardless of subjective arousal and valence.

We also found that during the encoding session, participants took longer to make like/dislike judgments for socially emotional stimuli than for biological stimuli. This result is also consistent with our hypothesis that the affective nature of biologically emotional stimuli can be detected more automatically than the affective nature of socially emotional stimuli.

Study 3

Study 3 examined the neural mechanisms underlying processing of biologically and socially emotional stimuli. Given previous evidence showing that the amygdala responds to both social and non-social emotional stimuli (e.g., Adolphs, 2003; Britton, et al., 2006; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002; Norris, et al., 2004), we expected that both biologically and socially emotional stimuli would induce similar activity in the amygdala. According to the results from Studies 1–2 and our hypothesis as outlined in Figure 1, however, we also expected different brain regions activated and different functional connectivity with the amygdala depending on stimulus type (i.e., biologically and socially emotional stimuli).

Past studies revealed that the amygdala is reciprocally interconnected with the visual cortex (Amaral, Behniea, & Kelly, 2003; Emery & Amaral, 2000), and that these two brain regions influence each other, which results in enhanced perceptual processing of emotional stimuli (Bradley, et al., 2003; Schupp, Junghöfer, Weike, & Hamm, 2003). If biologically emotional images hold visual attention more strongly than socially emotional images as revealed in Study 1, biologically emotional pictures should produce greater activity in visual cortex and stronger connectivity between the amygdala and visual cortex than do socially emotional pictures.

In contrast, previous research has suggested that medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) implements meta-cognitive or elaborative operations about emotional aspects of stimuli (Amodio & Frith, 2006; Cunningham, Johnson, Gatenby, Gore, & Banaji, 2003; Ochsner, Knierim, et al., 2004). If socially emotional stimuli trigger more elaborative processing than biologically emotional stimuli, MPFC should show stronger activation in response to socially emotional stimuli than to biologically emotional stimuli. In addition, if MPFC plays a critical role in processing the affective nature of social stimuli, the amygdala should have stronger functional connectivity with MPFC for socially emotional stimuli than for biological stimuli.

Study 3 also employed both pictorial stimuli and verbal stimuli to examine whether biologically and socially emotional stimuli recruit similar brain regions regardless of the stimuli format (i.e., word or picture). Two different predictions can be made concerning the brain regions underlying processing of words. First, if the conceptual meaning of the stimuli is critical, biologically emotional stimuli would activate similar brain regions, regardless of the format of the materials. Similarly, socially emotional words and pictures would activate overlapping regions of the brain. An alternative possibility is that once biologically emotional stimuli become abstract (i.e., verbal stimuli in this case), physical outcomes would be less evident than in pictorial stimuli, and therefore, they might need similar elaborative processing as socially emotional stimuli to evoke emotional reactions. In contrast, socially emotional stimuli would not imply direct physical outcomes, regardless of the stimulus formats, and both socially emotional words and pictures would need similar elaborative processing. Thus, an alternative prediction is that biologically emotional words recruit different brain regions from biologically emotional pictures but induce similar activation patterns to socially emotional stimuli, while socially emotional stimuli activate similar brain regions, regardless of the stimulus format. By including biologically and socially emotional words, we addressed these predictions.

Method

Participants

Sixteen Japanese University of Tsukuba undergraduates and graduate students took part in the experiment (12 males; Mage = 21.2, SD = 1.78). They gave informed consent in accordance with the MRI ethics committee of AIST. Prospective participants were excluded if they had any medical, neurological, or psychiatric illness. One participant judged more than 70% of social positive pictures and more than 60% of social negative pictures to be neutral during the task. Data from this participant were not included.

Materials: Emotional pictures

Twenty-eight biologically emotional pictures (14 positive, 14 negative), 28 socially emotional pictures (14 positive, 14 negative), and 28 neutral pictures were selected based on the pilot picture rating study. Social and biological pictures were matched not only in arousal and valence (see S-Table 1), but also in luminance (measured by Adobe Photoshop). Neutral pictures were also matched in luminance to the emotional pictures. We also included 14 scrambled images as nonsense stimuli. They were created based on three pictures from biological positive, biological negative, social positive, and social negative picture, and two neutral pictures used in the experiment.

Materials: Emotional words

Based on a pilot rating study of words (see Supplementary Materials), 28 biological (14 positive, 14 negative), 28 social (14 positive, 14 negative), and 28 neutral words were chosen (see S-Table 3). There were no differences in arousal or valence scores between the biological and social stimuli. In addition, 14 nonsense words were used in the experiment. Biological, social and neutral words were matched on familiarity obtained from published norms (Amano & Kondo, 2000).

Behavioral procedure

In each trial, participants saw either a word or a picture for 1800 ms. Words and pictures from the different emotion categories were randomly intermixed, with inter-stimulus intervals ranging from 6 to 8 secs. After each stimulus disappeared, participants were asked to indicate whether they liked, disliked, or were neutral about each stimulus by pressing buttons (see Supplementary Results for behavioral results).

Functional MRI data acquisition and preprocessing

All scanning was performed on a 3.0-T MRI Scanner (GE 3T Signa) equipped with EPI capability using the standard head coil for radiofrequency transmission and signal reception. Twenty-seven axial slices (4 mm thick and 0.2 mm gap, interleaved) were prescribed to cover the whole brain. A T2* weighted gradient echo EPI was employed. The imaging parameters were TR=2s, TE=30ms, FA=75, and FOV=20 cm×20 cm (64×64 mesh). Each participant’s data were individually pre-processed by SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging). In the preprocessing analysis, images were corrected for slice-timing and motion, then spatially normalized into the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template and spatially smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 8mm FWHM.

Whole-brain analysis

For each participant, stimulus-dependent changes in BOLD signal were modeled with regressors for each event type: neutral, biological positive, biological negative, social positive, social negative, and nonsense for each stimulus format (i.e., word and picture). The regressors were convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function provided by SPM. A high-pass filter (cutoff period = 128 s) was applied to remove low-frequency artifacts from the data. Effects of each event type were estimated using a fixed-effects model and then entered into a random effects analysis. Because preliminary fMRI analyses found similar patterns between positive and negative stimuli (see S-Tables 4–6), we report our main results from analyses with positive and negative valence categories collapsed.

In the whole-brain analysis, we performed two analyses. First, we assessed activity differences between biologically and socially emotional stimuli. The threshold was set at p < .05 -FDR at the cluster level with a height threshold of t = 3.79. Second, to reveal brain regions commonly activated by the two kinds of emotional stimuli, conjunction analyses were performed using the masking function in SPM. For this purpose, initial contrast analyses examined brain regions involved in processing each type of emotional stimuli compared with neutral and nonsense stimuli. These individual contrast analyses were then entered into conjunction analyses. The threshold for each contrast entered into a conjunction analysis was set at a voxel level p < .001 (uncorrected), which resulted in a conjoint probability of p < .00001. Clusters of activations that involved less than ten voxels were discarded. In both analyses, locations reported by SPM were converted into Talairach coordinates (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988) by the MNI-to-Talairach transformation algorithm (Lancaster, et al., 2007). The Talairach Daemon version 2.4.2 (Lancaster, et al., 2000) was then used to determine the nearest gray matter.

Region-of-interest analyses

As discussed above, we expected that biological and social stimuli would both activate the amygdala. However, the full-attention condition results of Study 2 suggest that there may be differences in hippocampal activity during viewing pictures, as participants remembered social stimuli more vividly than biological stimuli. To address these possibilities, we structurally defined bilateral amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus, based on AAL atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer, et al., 2002) and performed region-of-interest (ROI) analyses, using the MarsBar toolbox (Brett, Anton, Valabregue, & Poline, 2002).

Functional connectivity analyses

To examine functional connectivity with the amygdala, we applied a beta series correlation analysis (Gazzaley, Cooney, Rissman, & D’Esposito, 2005; Rissman, Gazzaley, & D’Esposito, 2004). This allowed us to use trial-to-trial variability to characterize dynamic inter-regional interactions. As a first step, a new GLM design file was constructed where each individual trial for each condition was coded with a unique covariate, resulting in 196 independent variables. To reduce the confounding effects of the global signal change, the global mean signal level over all brain voxels was calculated for each time point and was used as a covariate. Second, the least squares solution of the GLM yielded a beta value for each trial for each individual subject. These beta values were then sorted by stimulus type. As in the univariate analyses, we collapsed positive and negative stimuli in each stimulus type. As a third step, mean activity (i.e., mean parameter estimates) was extracted for each individual trial from a seed region identified in the whole-brain analysis. For each stimulus type, we then computed correlations between the seed’s beta series and the beta series of all other voxels in the brain, thus generating condition-specific seed correlation maps. Correlation magnitudes were converted into z-scores using the Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Finally, condition-dependent changes in functional connectivity were assessed using random-effects analyses, which were thresholded at p < .005-uncorrected at voxel-level combined with a cluster extent threshold of 20 contiguous voxels.

Results and Discussion

Below, we describe results for emotional pictures first, followed by results for emotional words.

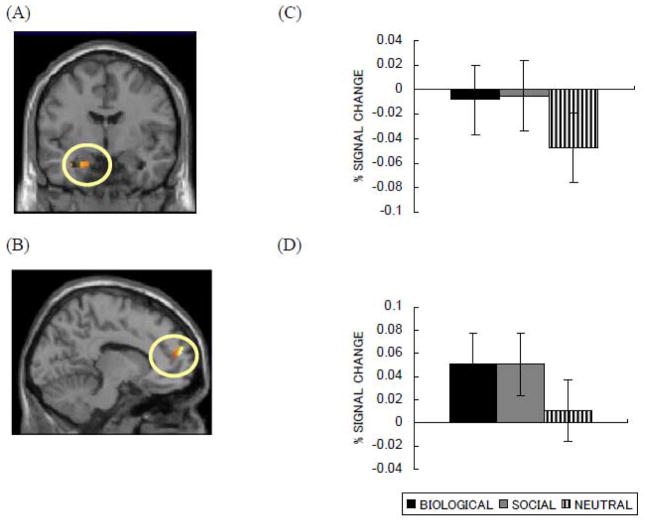

Brain areas shared by biological and social emotional pictures

A conjunction analysis between biological and social pictures revealed that both biological and social pictures induced activity in the left amygdala and the left MPFC (Table 1, Figure 6A and 6B). These results suggest that biologically and socially emotional images share some neural mechanisms.

Table 1.

Regions activated by both biologically and socially emotional pictures as revealed by a conjunction analysis.

| Area | H | BA | MNI | Talairach | T-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | ||||

| Amygdala | L | −34 | −4 | −24 | −32 | −3 | −18 | 4.86 | |

| L | −24 | −6 | −24 | −23 | −5 | −18 | 4.76 | ||

| MPFC | L | 9 | −10 | 58 | 22 | −10 | 50 | 29 | 4.32 |

| L | 9 | −10 | 52 | 14 | −10 | 46 | 21 | 4.07 | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | L | 13 | −46 | 24 | 4 | −44 | 20 | 9 | 4.51 |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | R | 7 | 28 | −60 | 54 | 24 | −63 | 47 | 5.11 |

| Fusiform Gyrus | R | 37 | 52 | −60 | −14 | 47 | −57 | −13 | 7.05 |

| Inferior/Middle Occipital Gyrus | L | 18 | −46 | −86 | −4 | −44 | −81 | −8 | 9.41 |

| L | 19 | −42 | −76 | 6 | −40 | −73 | 2 | 6.74 | |

| R | 37 | 48 | −70 | 4 | 43 | −68 | 2 | 7.78 | |

| R | 44 | −84 | −8 | 40 | −80 | −10 | 6.52 | ||

| Cerebellum | L | −44 | −54 | −30 | −42 | −49 | −28 | 7.17 | |

| L | −42 | −66 | −26 | −40 | −61 | −26 | 5.18 | ||

| L | −40 | −78 | −20 | −38 | −72 | −21 | 7.64 | ||

| R | 42 | −52 | −34 | 38 | −47 | −30 | 5.44 | ||

| R | 44 | −58 | −28 | 40 | −54 | −25 | 4.29 | ||

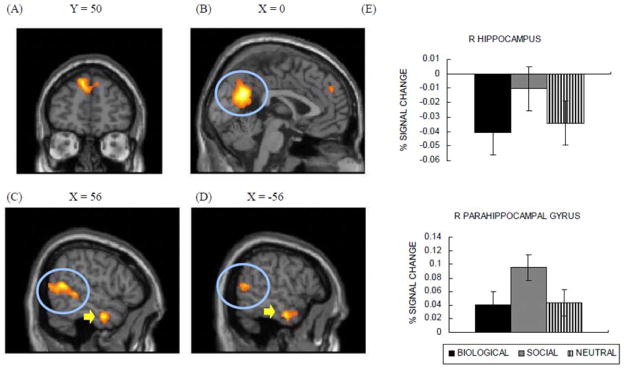

Figure 6.

Brain areas in which activity was associated with both biological and social pictures in Study 3: (A) left amygdala (Y = −5) and (B) left MPFC (x = −11). ROI analyses also revealed that both biologically and socially emotional pictures produced similar activity in (C) left and (D) right amygdala.

Brain areas sensitive to each type of emotional pictures

Despite the similarity revealed in the above conjunction analysis, a direct comparison revealed that relative to biological pictures, social pictures induced greater activity in bilateral MPFC (Figure 7A), which is a more dorsal part than the cluster revealed in the previous conjunction analysis. Dorsal MPFC has been implicated in elaborative processing of affective nature of stimuli (e.g., Ochsner, Knierim, et al., 2004). Thus, the greater MPFC activity to social stimuli seems consistent with our behavioral results that social stimuli need elaborative processing. Socially emotional pictures also activated other brain regions implicated in social cognition (e.g., Adolphs, 2003; Saxe, 2006), such as the posterior cingulate, bilateral temporal-parietal junction (TPJ), and the bilateral anterior temporal gyri (Table 2; Figure 7B–7D). In contrast, a reversed contrast (biological > social) revealed greater activity in the occipital gyrus and cerebellum (Figure 8). The stronger activity in the visual cortex for biological pictures is consistent with results in Study 1 that biological pictures hold visual attention more strongly than social pictures.

Figure 7.

Brain regions showing greater activity for socially emotional pictures than biological pictures (Study 3). Socially emotional pictures induced activity in dorsal MPFC (A), posterior cingulate (circled in (B)), bilateral temporo-parietal junction (circled in (C) and (D)), and bilateral anterior temporal gyri (pointed to with arrows in (C) and (D)). (E) Right hippocampus and right parahippocampal gyrus showed greater activity in response to social pictures than to biological pictures.

Table 2.

Brain regions showing greater activity for each type of emotional pictures.

| Area | H | BA | MNI | Talairach | K | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | ||||

| Social pictures > Biological pictures | |||||||||

| Posterior Cingulate/Precuneus | L | 23 | 0 | −62 | 26 | −1 | −62 | 22 | 1659 |

| L | 31 | −10 | −58 | 28 | −11 | −58 | 24 | ||

| R | 31 | 12 | −68 | 18 | 10 | −67 | 14 | ||

| MPFC | L | 8 | −8 | 54 | 40 | −9 | 45 | 44 | 432 |

| L | 8 | −4 | 50 | 34 | −5 | 42 | 39 | ||

| L | 9 | −10 | 64 | 22 | −10 | 56 | 29 | ||

| Anterior Temporal Gyrus | R | 21 | 56 | −4 | −28 | 51 | −3 | −20 | 310 |

| R | 21 | 48 | 6 | −40 | 44 | 7 | −30 | ||

| R | 47 | 34 | 14 | −30 | 31 | 14 | −21 | ||

| L | 21 | −58 | −8 | −26 | −54 | −7 | −21 | 221 | |

| L | 21 | −54 | 0 | −24 | −51 | 1 | −18 | ||

| L | 20 | −48 | −6 | −32 | −45 | −4 | −26 | ||

| Temporal-Parietal Junction | R | 39 | 56 | −56 | 12 | 51 | −55 | 11 | 608 |

| R | 22 | 56 | −40 | 0 | 51 | −39 | 1 | ||

| R | 19 | 56 | −70 | 10 | 51 | −68 | 8 | ||

| L | 39 | −56 | −60 | 12 | −53 | −58 | 9 | 272 | |

| L | 39 | −40 | −62 | 24 | −38 | −61 | 19 | ||

| L | 39 | −44 | −68 | 32 | −42 | −68 | 26 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Biological pictures > Social pictures | |||||||||

| Middle/Inferior Occipital Gyrus | R | 18 | 34 | −88 | 8 | 30 | −85 | 4 | 184 |

| R | 18 | 32 | −90 | 20 | 28 | −88 | 14 | ||

| Cerebellum | L | −32 | −60 | −28 | −30 | −55 | −27 | 203 | |

| R | 32 | −50 | −34 | 29 | −46 | −30 | 216 | ||

| R | 28 | −66 | −28 | 25 | −61 | −26 | |||

| R | 28 | −48 | −22 | 25 | −45 | −19 | |||

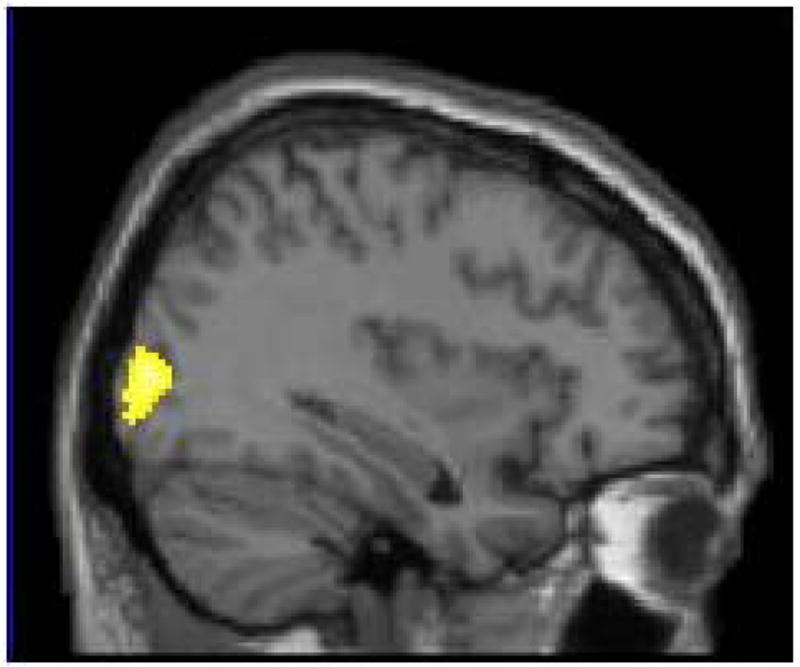

Figure 8.

Right occipital gyrus showed greater activity for biologically emotional pictures than for social ones (x = 34) in Study 3.

ROI analyses

The whole-brain analysis described above did not reveal significant differences between biological and social pictures in hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus activation. In ROI analyses, however, we found that social pictures produced greater activation in right hippocampus, F(1, 14) = 3.66, p < .08, η2 = .21, and in right parahippocampal gyrus, F(1, 14) = 8.80, p < .05, η2 = .39, than did biological pictures (Figure 7E). There were no significant differences in left hippocampus and left parahippocampal gyrus (ps > .20). Thus, consistent with the more detailed memory for social pictures seen in Study 2, socially emotional pictures evoked stronger activity in memory-related regions than did biologically emotional pictures. In contrast, the bilateral amygdala showed similar activity between biological and social pictures (ps > .90; Figure 6C and 6D), which is consistent with the results from the previous conjunction analysis.

Functional connectivity analyses

To address the functional connectivity with the amygdala, a beta series correlation analysis was applied. As a seed region, we employed a 3-mm sphere surrounding the peak amygdala voxel from the conjunction analysis of brain regions shared by biological and social emotional pictures ([−34, −4, −24] hereafter all coordinates in text are in the MNI space).

This amygdala seed region had stronger functional connectivity with occipital lobe and inferior parietal lobe regions for biological pictures than social pictures (Table 3; Figure 9A). This stronger interconnection between amygdala and visual processing might facilitate bottom-up visual attention to biologically emotional stimuli, which in turn could contribute to the stronger attention effects of biologically emotional pictures revealed in Study 1.

Table 3.

Results from functional connectivity analyses. Areas showing greater correlation with left amygdala for either biological or social pictures.

| Area | H | BA | MNI | Talairach | T-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | ||||

| Biological pictures > Social pictures | |||||||||

| Inferior Parietal Lobule | R | 40 | 46 | −54 | 44 | 41 | −56 | 39 | 5.19 |

| Middle Occipital Gyrus | R | 19 | 38 | −82 | 12 | 34 | −79 | 8 | 3.33 |

| Occipital Lobe, Lingual Gyrus | R | 6 | 36 | −74 | 8 | 32 | −72 | 5 | 4.60 |

| R | 18 | 6 | −80 | −4 | 4 | −76 | −6 | 3.98 | |

| Precuneus | R | 7 | 10 | −76 | 56 | 7 | −77 | 48 | 4.91 |

|

| |||||||||

| Social pictures > Biological pictures | |||||||||

| MPFC | L | 8 | −16 | 46 | 36 | −16 | 38 | 40 | 3.93 |

| Posterior Parahippocampal Gyrus | L | 30 | −26 | −54 | 4 | −25 | −52 | 2 | 5.05 |

| L | 30 | −20 | −48 | 10 | −20 | −47 | 8 | 3.26 | |

| Uncus | L | 20 | −34 | −6 | −32 | −32 | −4 | −26 | 4.13 |

| Middle Cingulate Gyrus | L | 24 | −12 | 6 | 52 | −13 | −1 | 51 | 3.95 |

| R | 24 | 22 | −4 | 44 | 19 | −9 | 43 | 5.99 | |

| R | 31 | 18 | −16 | 38 | 15 | −20 | 37 | 4.84 | |

| R | 24 | 14 | −8 | 40 | 11 | −13 | 39 | 4.10 | |

| Precentral Gyrus | L | 4 | −18 | −18 | 56 | −18 | −23 | 52 | 6.21 |

| L | 4 | −28 | −20 | 60 | −28 | −25 | 55 | 5.01 | |

| R | 4 | 14 | −24 | 68 | 11 | −30 | 63 | 4.79 | |

| Paracentral Lobule | L | 31 | −6 | −26 | 48 | −7 | −30 | 45 | 5.98 |

| L | 5 | −12 | −26 | 56 | −13 | −31 | 52 | 5.19 | |

| R | 5 | 22 | −32 | 54 | 19 | −36 | 50 | 4.35 | |

| Postcentral Gyrus | L | 3 | −26 | −28 | 58 | −26 | −33 | 53 | 4.47 |

| L | 4 | −34 | −34 | 60 | −33 | −39 | 54 | 4.52 | |

| Inferior/Middle Temporal Gyrus | L | 20 | −48 | −12 | −26 | −45 | −10 | −21 | 4.17 |

| L | 21 | −52 | −4 | −28 | −49 | −3 | −22 | 3.19 | |

Figure 9.

Brain regions showing differential functional connectivity with the amygdala across biologically and socially emotional pictures (Study 3). (A) Inferior parietal lobe (circled), and occipital cortex (pointed to with arrows) showed stronger connectivity with left amygdala for biological pictures than for social pictures. (B) In contrast, dorsal MPFC showed stronger connectivity for social pictures than for biological pictures.

In contrast, the same amygdala seed region had a stronger correlation with left dorsal MPFC for social pictures than for biological pictures (Figure 9B). Thus, it appears that dorsal MPFC implements elaborative processing about socially emotional stimuli and sends its outcome to the amygdala during like/dislike judgments. In addition, the amygdala had stronger correlations with left uncus and with posterior parahippocampal gyrus for social pictures than for biological pictures (Table 3). These results are consistent with the results from ROI analyses and Study 2, suggesting that people remember socially emotional stimuli more strongly than biologically emotional stimuli if they have enough cognitive resources.

Brain areas sensitive to emotional words

Finally, we examined brain activity induced by emotional words. Unlike emotional pictures, we did not find significant differences when we contrasted biologically emotional words to socially emotional words (and vice versa). This suggests that biologically and socially emotional words induce similar brain activity. To address this possibility, we employed two conjunction analyses.

Conjunction between emotional pictures and emotional words

First, we examined whether emotional words produced activity in similar regions to emotional pictures in each type of stimuli (i.e., biological and social). A conjunction analysis between social words and social pictures revealed activations in dorsal MPFC, posterior cingulate, TPJ and anterior temporal gyrus (Table 4; Figure 10). In contrast, there were no brain regions shared by biological words and biological pictures even at a lower threshold level (p < .005 -uncorrected for each contrast entered into the conjunction analysis). Thus, it appears that socially emotional stimuli recruit similar brain regions irrespective of stimulus formats, whereas biologically emotional words produce activity in different brain regions from biological pictures.

Table 4.

Results from conjunction analyses between emotional words and emotional pictures in Study 4.

| Area | H | BA | MNI | Talairach | T-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | ||||

| Social words and Social pictures | |||||||||

| Posterior Cingulate | L | 31 | −4 | −58 | 26 | −5 | −58 | 22 | 6.11 |

| MPFC | L | 9 | −2 | 56 | 16 | −3 | 49 | 23 | 5.84 |

| R | 9 | 10 | 60 | 16 | 8 | 53 | 24 | 5.80 | |

| L | 9 | −8 | 60 | 26 | −9 | 52 | 32 | 5.16 | |

| Temporal-Parietal junction | L | 19 | −50 | −64 | 18 | −48 | −63 | 14 | 5.02 |

| L | 39 | −56 | −72 | 18 | −53 | −70 | 13 | 4.63 | |

| Anterior Temporal Gyrus | L | 38 | −38 | 16 | −42 | −36 | 17 | −33 | 4.53 |

| L | 21 | −50 | 0 | −36 | −47 | 2 | −29 | 4.51 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Biological words, Social words and Social pictures | |||||||||

| Anterior Temporal Gyrus | L | 38 | −46 | 12 | −36 | −43 | 13 | −28 | 4.85 |

| L | 21 | −52 | 4 | −38 | −49 | 6 | −30 | 4.05 | |

| Precuneus/Posterior Cingulate | L | 31 | −8 | −64 | 24 | −9 | −63 | 20 | 3.88 |

| L | 30 | −4 | −60 | 16 | −5 | −59 | 13 | 3.71 | |

| Temporal-Parietal junction | L | 39 | −56 | −72 | 22 | −53 | −70 | 17 | 3.66 |

| L | 39 | −46 | −68 | 20 | −44 | −67 | 15 | 3.18 | |

| MPFC | L | 8 | −6 | 58 | 40 | −7 | 49 | 45 | 3.56 |

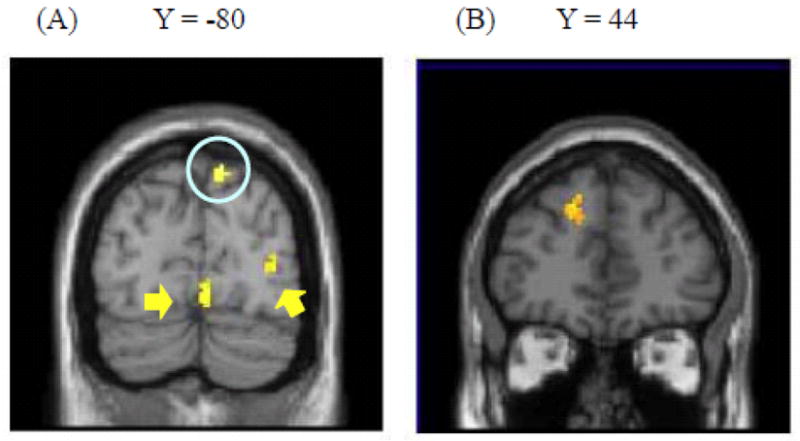

Figure 10.

Results from the conjunction analysis between socially emotional words and socially emotional pictures in Study 3. Posterior cingulate (circled in (A)), MPFC (pointed to by an arrow in (A) and (B)), temporo- parietal junction (circled in (C)), and anterior temporal gyrus (pointed to by an arrow in (C)) showed greater activity for both socially emotional words and socially emotional pictures.

Conjunction analyses between socially and biologically emotional words

Next, we performed another conjunction analysis between biological words and social words. Although this conjunction analysis did not find any significant results at the same threshold level, we found activity in left anterior temporal lobe (−46, 12, −36: BA 38), left TPJ (−58, −64, 30: BA 39), left precuneus/posterior cingulate (−8, −66, 24: BA 31), and dorsal MPFC (−6, 58, 40: BA 8) at a lower threshold level (p < .005 -uncorrected for each contrast in the conjunction analysis). These clusters were similar to the clusters in which we found greater activity for socially emotional pictures than for biologically emotional pictures (see Table 2), suggesting that biologically emotional words recruit similar brain regions to socially emotional stimuli.

To confirm this possibility, we performed another conjunction analysis, where we looked at the common regions among three contrasts (i.e., social pictures, social words, and biological words) with p < .005-uncorrected for each contrast entered in the conjunction analysis. This conjunction analysis revealed activity in left anterior temporal gyrus, dorsal MPFC, left TPJ and posterior cingulate (Table 4). Thus, while biological words did not produce significant activity in any regions overlapping with biological pictures, they evoked activity in similar regions as social stimuli. These results suggest that once biologically emotional stimuli become abstract, they are processed in a similar way as socially emotional stimuli.6

General Discussion

Past studies on emotion and cognition have shown that valence and arousal modulate attention and memory encoding (for reviews see Dolcos & Denkova, 2008; Kensinger, 2009; Mather & Sutherland, in press). However, the present study reveals that subjective arousal and valence are not enough to explain the effects of emotion; whether the image is directly relevant to biological motivations, such as survival or reproduction, is an additional important factor.

Effects of Biologically and Socially Emotional Stimuli on Attention and Memory

In Study 1, we found that biologically emotional images capture attention more than socially emotional images. Although we matched arousal and valence level between biologically and socially emotional images, socially emotional images did not impact attention differently than neutral images. Study 2 revealed that memory of socially emotional images is enhanced through elaborative processing, while memory of biologically emotional images is enhanced automatically: Participants’ memory of socially emotional pictures was impaired when their cognitive resources were deployed elsewhere, whereas the attention manipulation did not significantly influence memory of biologically emotional pictures. Furthermore, arousal and valence did not modulate the effects of biological relevance in either Studies 1 or 2. Additional analyses also confirmed similar results even after controlling for the effects of visual complexity or presence of people (S-Figure 2; see Supplementary Results for details). Thus, our behavioral studies suggest that biologically emotional images can induce emotional reactions more automatically than socially emotional stimuli, which further results in automatic influences on attention and memory encoding (see Figure 1).

Past studies have revealed that perceiving an emotional stimulus modulates subsequent cognitive processing, enhancing processing of high-salience stimuli while reducing processing of low-salience stimuli (see Mather & Sutherland, 2011 for a review). The results from the current study further suggest that not all emotional materials can induce emotional reactions in an automatic/immediate way. Thus, it appears that biologically emotional stimuli can induce emotional reactions automatically and have a more direct and automatic pathway to influence cognition, while socially emotional stimuli require elaborative processing to modulate cognitive processing.

Neural Mechanisms Underlying Processing of Biologically and Socially Emotional Stimuli

Using fMRI, Study 3 revealed both similar and different brain regions involved in processing biologically emotional stimuli and socially emotional stimuli. We found that the amygdala and MPFC showed significant activity in response to both biologically and socially emotional pictures. In fact, these separate activations involved overlapping voxels as shown in the conjunction analysis. This suggests that biologically and socially emotional images share some neural mechanisms. However, there were also substantial differences in the brain regions involved in biologically versus socially emotional pictures.

Biologically emotional pictures recruited greater activity in the occipital gyrus than did socially emotional pictures. In addition, activity in the amygdala was more positively correlated with activity in the occipital gyrus during viewing of biologically emotional pictures than during viewing of social pictures. This greater visual cortex activation is consistent with the enhanced attention effects of biologically emotional pictures revealed in Study 1, suggesting that the amygdala’s arousal response is more related to the visual features of the biologically emotional pictures than to the visual aspects of the socially emotional pictures.

In contrast, socially emotional pictures induced greater activity in dorsal MPFC than did biologically emotional pictures. Furthermore, the amygdala was more positively correlated with dorsal MPFC for socially emotional images than for biological images. The dorsal MPFC has been associated with elaborative processing of emotional aspects of stimuli (Cunningham, et al., 2003; Ochsner, Knierim, et al., 2004) and with performing tasks that require deep processing of affective nature of stimuli (e.g., Johnson, et al., 2006; J. P. Mitchell, Banaji, & Macrae, 2005; Norris, et al., 2004; Ochsner, Knierim, et al., 2004), such as emotion regulation (Ochsner, Ray, et al., 2004; Phan, et al., 2005), moral judgments (Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002), and theory-of-mind task (Gallagher, et al., 2000). In addition, activity in dorsal MPFC has been associated with successful memory encoding of socially emotional stimuli (Harvey, Fossati, & Lepage, 2007). Together with these previous findings, our findings suggest that socially emotional pictures require more elaborative processing implemented by dorsal MPFC to modulate cognitive processing and to elicit the activity in the amygdala than do biologically emotional pictures.

Additional brain regions associated with socially emotional stimuli

In addition to dorsal MPFC, socially emotional pictures activated brain regions implicated in social cognition (Adolphs, 2003; Saxe, 2006), such as TPJ, anterior temporal lobe, and posterior cingulate/precuneus. Although these areas did not produce significant results in the functional connectivity analysis, they may also play important roles in processing of socially emotional pictures.

For instance, the anterior temporal lobe has been implicated in conceptual processing of social stimuli; it activates during semantic judgments about social stimuli (J. P. Mitchell, Heatherton, & Macrae, 2002; Zahn, et al., 2007; Zahn, et al., 2009), retrieval of other people’s names (Tsukiura, Mochizuki-Kawai, & Fujii, 2006), and learning of facts about other people (e.g., age, occupation; Simmons, Reddish, Bellgowan, & Martin, 2010).

In contrast, posterior cingulate and precuneus have been implicated in self-referential processing (Johnson, et al., 2006), perspective taking (Ruby & Decety, 2001), episodic recollection (Wagner, Shannon, Kahn, & Buckner, 2005), and simulation of others’ behaviors (Calvo-Merino, Glaser, Grezes, Passingham, & Haggard, 2005). Although a precise role of this area is still not fully understood, all of these tasks involve detailed mental representations. Thus, this area may help implement internally generated representations (Cavanna & Trimble, 2006).

Finally, TPJ has been implicated in orienting attention to relevant stimuli that are outside the focus of attention (Corbetta, Kincade, & Shulman, 2002; J. P. Mitchell, 2008). For instance, TPJ activity was associated with social tasks that require people to direct their attention from what they think to what other people think, such as theory-of-mind task (Saxe & Kanwisher, 2003; Young, Cushman, Hauser, & Saxe, 2007).

These previous findings provide clues about the ensemble of cognitive processes needed for socially emotional stimuli: a) conceptual processing and semantic interpretation of presented stimuli -- implemented by the anterior temporal lobe, b) mental imagery about the represented situations to simulate others’ feelings or thoughts -- implemented by posterior cingulate/precuneus, and c) attention reoriented from one’s own feelings and thoughts to others’ thoughts or feelings -- implemented by the TPJ. Further research is needed to address how the dorsal MPFC and the amygdala interact with these brain regions during processing of socially emotional materials.

Underlying Mechanisms of Automatic Effects of Biologically Emotional Stimuli

Next, we turn to the question of why biologically emotional pictures modulate cognitive processing more automatically than do socially emotional pictures.

Evolutionary relevance

One possibility is that biologically emotional pictures involve evolutionary threats that have been recurrent problems in human ancestral environments, which might have resulted in the preferential processing of those stimuli. In fact, some of the biologically emotional stimuli employed in the current study have been considered to be evolutionarily threatening (e.g., snake, spider; Öhman & Mineka, 2001) and revealed to be processed automatically (Öhman, 2002; Öhman, Flykt, et al., 2001), which is consistent with the findings about biologically emotional stimuli in the current study.

In Study 1, however, participants detected the dot-probe significantly slower after biological pictures than after social pictures, regardless of whether they were evolutionary threats or not (see Supplementary Methods and Results for details). Likewise, in Study 2, dividing attention did not have significant effects on memory for biologically emotional images not depicting an evolutionary threat. Furthermore, both in Studies 1 and 2, angry faces (i.e., evolutionarily threatening, but social stimuli) showed similar patterns to other socially emotional stimuli. Consistent with these results from post-hoc analyses, previous research which compared evolutionary threats (e.g., snakes) with non-evolutionary threats (e.g., guns) found that the two types of threats had similar effects on attention (Blanchette, 2006; Brosch & Sharma, 2005; Carlson, et al., 2009; Fox, et al., 2007) and aversive conditioning (Hugdahl & Johnsen, 1989). Taken together, it seems unlikely that the automatic effects we observed with biologically emotional stimuli are attributable to the effects of evolutionary threats.

Saliency/ambiguity of physical manifestations

Instead, we argue that the differences in processing biological and social emotional stimuli are due to whether the physical manifestations of a situation are salient or ambiguous. Biologically emotional pictures depict situations highly related to survival or reproduction. Therefore, they would imply clear and direct physical outcomes, such as death, injuries, satiety, and sexual experiences, irrespective of contexts. This clear and context-independent nature of biologically emotional stimuli might allow people to extract the affective meanings of the stimuli without elaborative processing, which results in the automatic influences on cognitive processing. In contrast, the same social stimulus could have different meanings and outcomes depending on contexts. Thus, the meanings and the outcomes are less obvious in socially emotional stimuli, which could explain the absence of their automatic influences on cognitive processing.

In fact, the results from Study 3 suggest that the saliency of physical manifestations plays a more important role than whether stimuli are conceptually relevant with survival/reproduction or social life. In Study 3, we found little overlap between biological pictures and words, and biological words produced activity in similar regions as did socially emotional stimuli. Although biological words are conceptually related to survival or reproduction, the physical manifestations are less obvious from the visual features of biological words than from those of biological pictures. As a consequence, biological words might require more elaborative processing than biological pictures to elicit an affective reaction, which might have resulted in similar brain activation patterns to socially emotional stimuli.

However, past studies employing taboo words revealed that highly arousing biological words can have automatic influences on attention (e.g., Anderson, 2005; MacKay, et al., 2004; Mathewson, et al., 2008). Since these results were consistent with the findings about biologically emotional images in the current study, they suggest that biological relevance can have a significant impact even when the saliency of physical manifestations is low. Further research should manipulate both the biological/social relevance and the saliency of the physical outcomes to clarify the role of each factor in emotional processing.

In addition, there might be other differences between biological and social emotional stimuli that are more responsible for the current results than the biological/social relevance or the saliency of the physical outcome. In the current study, we controlled the effects of the two dimensions (i.e., arousal and valence) that have been predominantly examined in the past literature on emotion and cognition. Similar results were also obtained after controlling the effects of visual complexity, the presence of people, and the evolutionary threats. Furthermore, in Study 3, we controlled luminance and frequency. However, biologically and socially emotional stimuli might differ in other ways, such as semantic relatedness (Talmi, et al., 2007), relevance to approach/avoidance behaviors (Wentura, Rothermund, & Bak, 2000), or how strongly the stimulus induces certain actions/behaviors (Frijda, Kuipers, & ter Schure, 1989). Future research should address the effects of biological/social relevance while considering these other factors to clarify which dimension of emotional stimuli is more crucial.

Questions for Future Research

Several other questions also remain for further work. First, past research found that highly arousing stimuli are attended to (Anderson, 2005; Knight, et al., 2007) and memorized (Kensinger & Corkin, 2004) more automatically than low arousing stimuli. These observations are similar to the patterns we found in biologically emotional pictures, suggesting the possibility that some of the previous findings of arousal effects might be due to biological relevance, instead of arousal per se. In fact, in our two pilot rating studies and S-Study 1, relevance to survival/reproduction was positively correlated with arousal ratings even after controlling for the effects of the social relevance (see S-Table 7). Future research should manipulate both arousal level and motivational relevance, to clarify the effects of motivational relevance, the effects of arousal and interactions between them.

Second, the current article focused on two kinds of emotional stimuli: those highly relevant to survival/reproduction and low in relation to social adaptation and those highly relevant to social adaptation but low in relation to survival/reproduction. Although this categorical approach allowed us to demonstrate the effects of the biological/social relevance, in real life, emotional stimuli sometimes relate to both survival/reproduction and social adaptation. For example, in addition to their survival value, certain foods (such as a birthday cake) might evoke emotion via their social meanings. Similarly, some social stimuli (e.g., one’s family) might have significance not only in social adaptation but also in reproduction (e.g., raising their offspring). In addition, we did not include stimuli that are related to participants’ own survival (e.g., real foods) or social life (e.g., their friends); these stimuli might influence cognitive processing differently from stimuli that depict biologically/socially emotional objects but are not actually relevant with participants’ own survival or social life (e.g., pictures depicting foods). Further research employing more fine-grained categorizations of emotional stimuli is needed to elucidate how the biological and social relevance modulate emotional processing.

A third question concerns whether biological and social relevance influence processing of neutral materials. In fact, previous studies demonstrated that neutral words rated for relevance to a grasslands survival scenario were remembered better than words encoded under other deep processing conditions (e.g., Nairne, Pandeirada, Gregory, & Van Arsdall, 2009; Nairne, Pandeirada, & Thompson, 2008; Weinstein, Bugg, & Roediger, 2008), suggesting that even the processing of neutral stimuli may benefit from survival relevance.

But it is difficult to disentangle the effects of biological relevance and arousal. For instance, rating neutral words for their relevance to a survival scenario was done in the context of higher arousal than in the control condition (Soderstrom & McCabe, 2011). In the current research, biological relevance was positively correlated with arousal in the two pilot studies and S-Study 1, even after controlling the effects of social relevance (see S-Table 7). Furthermore, when people had strong biological needs (e.g., thirst), neutral stimuli that satisfied the biological need (e.g., water) were evaluated positively (not as neutral stimuli; Ferguson & Bargh, 2004). These results suggest that biological relevance increases emotionality, and that it is hard to define neutral but biologically relevant stimuli. In contrast, given that the social relevance had weaker correlations with arousal than biological relevance (S-Table 7), there should be neutral stimuli relevant to social life (e.g., Norris, et al., 2004). These social but neutral stimuli might induce similar elaborative processing as socially emotional stimuli in order for people to interpret their meaning. Further research should address whether the social relevance has similar effects for emotional and neutral stimuli.

Another question concerns processing of angry faces. While angry faces have been associated with automatic attention (e.g., Öhman, Lundqvist, & Esteves, 2001), the reaction times to detect the dot-probe were not different across angry faces, other social stimuli and neutral stimuli in Study 1 (see Supplementary Results for details). Similarly, in Study 2, angry faces were remembered better than neutral pictures in the full-attention condition, but the enhancement disappeared in the divided-attention condition. These results were consistent with recent neuroimaging findings that processing emotional faces requires cognitive resources (e.g., Pessoa, McKenna, Gutierrez, & Ungerleider, 2002; Pessoa, Padmala, & Morland, 2005).