Abstract

Collective rituals are ubiquitous and resilient features of all known human cultures. They are also functionally opaque, costly, and sometimes dangerous. Social scientists have speculated that collective rituals generate benefits in excess of their costs by reinforcing social bonding and group solidarity, yet quantitative evidence for these conjectures is scarce. Our recent study measured the physiological effects of a highly arousing Spanish fire-walking ritual, revealing shared patterns in heart-rate dynamics between participants and related spectators. We briefly describe our results, and consider their implications.

Keywords: joint action, arousal, synchrony, anthropology

Collective rituals are a puzzling aspect of human behavior. They are ubiquitous, resilient, and evoke powerful emotions and commitments, yet they are functionally opaque and lack straightforward payoffs.1 This evolutionary cost problem2–4 is particularly evident among highly stressful rituals, which often tempt bodily harm. Social scientists have long speculated that collective rituals generate benefits exceeding their costs by reinforcing social bonding and group solidarity.5,6 Famously, Emile Durkheim proposed the notion of collective effervescence,7 a feeling of belonging and assimilation produced by collective ritual action. Yet, there is little numerical evidence for this conjecture.8 More generally, the mechanisms that drive solidarity effects remain unclear. Two hypotheses about mediating mechanisms stand out: according to a “coordinated movement” hypothesis [H1], it is the harmonization of movements that aligns the cognitive and affective states of participants, evoking heightened solidarity.9–12 According to an “empathetic projection” hypothesis [H2], it is the imagined responses of participants to focal events of the ritual that align their relevant cognitive states, without any strict need for orchestrated motor coordination.13–15 While H1 and H2 are compatible, and indeed such effects may interact,9 the relative importance of movement and empathy for naturally occurring rituals remains an open question.

In a recent study of a highly arousing fire-walking ritual,16 we quantified shared patterns in heart-rate dynamics between fire-walkers and spectators during the event to examine whether these effects would be mediated by partaking of the same ordeal and prior social affiliation. The study was conducted in the Spanish village of San Pedro Manrique, where a fire-walking ceremony takes place annually as part of the festival of San Juan. This ceremony is the biggest event in the area, performed in a specially constructed venue with a capacity of 3,000 people, five times the local population. At the climax of the ceremony, a few dozens locals take their place at the center of the venue, and one by one cross a bed of glowing coals,i carrying a beloved one on their backs (Fig. 2). Although the ritual is not explicitly religious, it carries tremendous importance for the locals.

Figure 2.

Fire-walkers go through their ordeal carrying a beloved one at their back.

Hypothesizing that synchronous arousal would be detectable in certain physiological states of ritual participants, we measured the heart rates of performers and spectators during the ceremony. Based on our hypothesis that empathetic arousal is one mechanism that facilitates social bonding [H2], we expected to find shared arousal among fire-walkers as well as spectators, even though the latter merely witnessed without performing the key ritual action sequences. We obtained data from 12 fire-walkers, nine spectators who were either relatives or friends of at least one fire-walker (“related spectators”), and 17 unrelated visitors-spectators. Data were analyzed for two source epochs, the entire 30 min duration of the fire-walk, and a 30 min baseline recorded a few hours before the ritual, using recurrence quantification analysis (RQA) on individual data, and cross-recurrence quantification analysis (CRQA) on paired participants’ data.

For intra-personal effects, recurrence plots17 revealed global similarities between fire-walkers and related spectators, but not unrelated spectators. For quantification, four RQA measures were compared (%DETerminism, MAXLine, Entropy, Laminarity) using a 3x2 mixed model MANOVA, with the group as a between-subject variable, and the source epoch (ritual vs. baseline) as a within-subjects variable. The analysis yielded a significant main effect of the group [F(8,64) = 2.75, p < 0.011], a significant interaction [F(8,64) = 3.869, p < 0.001], but only a marginal effect of the source epoch (p = 0.077). Post-hoc analyses revealed differences between fire-walkers and nonrelated spectators, but did not distinguish fire-walkers from related spectators (only in stability, i.e., MAXLine).

Inter-personal effects were investigated using CRQA, a bivariate extension of RQA.18 The four key measures were compared using a similar design, with relatedness as the between-subjects variable, and the source epoch as the within-subjects variable. The MANOVA yielded a main effect of relatedness [F(8,24) = 3.508, p < 0.008], a main effect of the ritual [F(4,12) = 9.473, p < 0.001], and a marginal interaction, p = 0.079. Post-hoc tests revealed no differences between the related and marginally related pairs, but showed lower shared dynamics with the unrelated pairs.

Importantly, our data indicate that ritual effects are more intricate and subtle than suggested by the qualitative concept of “collective effervescence.” Specifically, the analysis revealed a strong alignment among the heart rates of fire-walkers and related spectators, showing an associative empathetic response, which operates irrespectively of personal activity and experience of fire-walking, thus supporting H2. This response, however, did not extend to non-related spectators, indicating that patterns of arousal are not merely driven by the individualistic qualities of the ritual, but are also subjectively, socially, and emotionally mediated in response to the performances of others. Remarkably, spectators who were related to at least one fire-walker exhibited shared patterns of arousal also to fire-walkers they were not closely related to. This suggests that the ritual extends a boundary of empathetic concern with network-like effects, from related to unrelated performers.

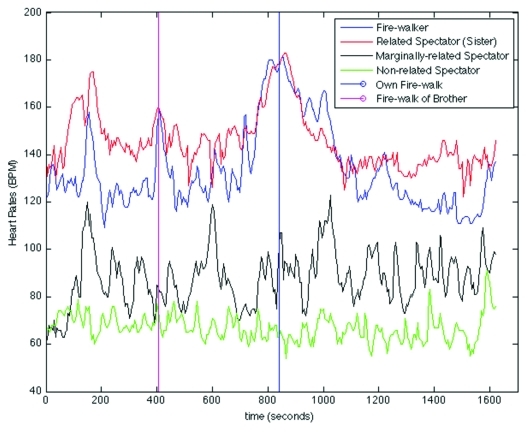

Finally, our data indicate that merely observing a ritual may be insufficient to produce collective emotions of the kind and/or degree experienced by the performers and their supporters. Shared arousal among spectators was discovered only among those who previously identified with at least one fire-walker, with levels of sharing predicted by prior association, and for those with the strongest responses, by participation in the central ritual ordeal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Heart-rates (in beats per minute) during the ritual from a representative fire-walker (blue), related sister-spectator (red), marginally related spectator (related to another fire-walker, black), and non-related spectator (green). The blue and pink vertical lines mark the time the fire-walker and his brother cross the fire, respectively.

While no study could hope to explain more than a small fraction of something so complex as a collective ritual, our investigation revealed levels of intricacy and refinement unavailable to qualitative ethnography. Far from being antagonistic to cultural anthropology, quantitative field experiments suggest the prospect for unprecedented power in the detection of sociocultural signals that remain elusive to classical methodologies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Merlin Donald and Robert Rowthorn for their insightful comments.

Footnotes

In 2008, the surface temperature of the coals was measured at 677°C (1250°F).

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/17609

References

- 1.Sørensen J. Acts that work: cognitive aspects of ritual agency. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 2007:281-300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irons W. Religion as a Hard-to-Fake Sign of Commitment. In: Nesse RM, ed. Evolution and the Capacity for Commitment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001:292-309. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulbulia J. The cognitive and evolutionary psychology of religion. Biol Philos. 2004;19:655–86. doi: 10.1007/s10539-005-5568-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sosis R. Why aren’t we all hutterites? Hum Nat. 2003;14:91–127. doi: 10.1007/s12110-003-1000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radcliffe-Brown AR. Structure and function in primitive society, essays and addresses. London: Cohen & West, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rappaport RA. The obvious aspects of ritual. In: Rappaport RA, ed. Ecology, Meaning, and Religion. Richmond: North Atlantic Books, 1979:173-221. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durkheim E. The elementary forms of religious life. New York: Free Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sosis R, Ruffle B. Religious Ritual and Cooperation: Testing for a Relationship on Israeli Religious and Secular Kibbutzim 1. Curr Anthropol. 2003;•••:713–22. doi: 10.1086/379260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdesolo P, DeSteno D. Synchrony and the social tuning of compassion. Emotion. 2011;2:262–6. doi: 10.1037/a0021302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiltermuth S0S, Heath C. Synchrony and cooperation. Psychol Sci. 2009;1:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hove MJ, Risen JL. It's all in the timing: interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc Cogn. 2009;27:949–60. doi: 10.1521/soco.2009.27.6.949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chartrand TL, Bargh JA. The chameleon effect: The perception–behavior link and social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;6:893–910. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vignemont F, Singer T. The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson PL, Rainville P, Decety J. To what extent do we share the pain of others? Insight from the neural bases of pain empathy. Pain. 2006;125:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer T, Lamm C. The social neuroscience of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konvalinka I, Xygalatas D, Bulbulia J, Schjødt U, Jegindø E-M, Wallot S, et al. Synchronized arousal between performers and related spectators in a fire-walking ritual. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011:8514-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marwan N, Carmen Romano M, Thiel M, Kurths J. Recurrence plots for the analysis of complex systems. Phys Rep. 2007;438:237–329. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2006.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shockley K, Butwill M, Zbilut JP, Webber CL. Cross recurrence quantification of coupled oscillators. Phys Lett A. 2002;305:59–69. doi: 10.1016/S0375-9601(02)01411-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]