Abstract

Macrophages rely on reverse cholesterol transport mechanisms to rid themselves of excess cholesterol. By reducing accumulation of cholesterol in the artery wall, reverse cholesterol transport slows or prevents development of atherosclerosis. In stable macrophages, efflux mechanisms balance influx mechanisms and accumulating lipids do not overwhelm the cell. Under atherogenic conditions, inflow of cholesterol exceeds outflow and the cell is ultimately transformed into a foam cell, the prototypical cell in the atherosclerotic plaque. Adenosine is an endogenous purine nucleoside released from metabolically active cells by facilitated diffusion and generated extracellularly from adenine nucleotides. Under stress conditions, such as hypoxia, a depressed cellular energy state leads to an acute increase in the extracellular concentration of adenosine. Extracellular adenosine interacts with one or more of a family of G protein coupled receptors (A1, A2A, A2B and A3) to modulate the function of nearly all cells and tissues. Modulation of adenosine signaling participates in regulation of reverse cholesterol transport. Of particular note for the development of atherosclerosis, activation of A2A receptors dramatically inhibits inflammation and protects against tissue injury. Potent anti-atherosclerotic effects ofA2A receptor stimulation include inhibition of macrophage foam celltransformation and upregulation of the reverse cholesterol transport proteins cholesterol 27-hydroxylase and ATP binding cassette transporter (ABC) A1. Thus, A2A receptor agonists may correct or prevent the adverse effects of inflammatory processes on cellular cholesterol homeostasis. This review focuses on the importance of extracellular adenosine acting at specific receptors as a regulatory mechanism to control the formation of foam cells under conditions of lipid loading.

INTRODUCTION

Adenosine, a purine nucleoside normally found at low concentrations in human tissues, is released into the extracellular space in response to metabolic stress such as that encountered during inflammatory events or during tissue hypoxia or ischemia. During ischemia, adenosine is endogenously produced in the heart as a result of ATP catabolism.1 It is well-established that adenosine exerts multiple potent cardioprotective effects on the ischemic/reperfused heart, attenuating reversible and irreversible myocardial injury.2 Adenosine acts as an immunomodulator with anti-inflammatory properties and has antiplatelet effects, all of which can be atheroprotective. It downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages. 3 Adenosine suppresses macrophage activation by interferon (IFN)-γ, a cytokine centrally involved in promoting atherosclerosis.4, 5

In evaluating the impact of adenosine on cardiovascular function, recent studies have focused on aspects of the atherosclerotic process. Atherosclerosis involves both lipid accumulation and activation of inflammatory pathways in multiple cell types and, perhaps most importantly, in macrophages.6 This review will discuss the influence of activation of specific adenosine receptors on cell types present in the vessel wall that contribute to atherosclerosis or its prevention. These cell types include endothelium and monocytes/macrophages. Special attention will be given to adenosine effects on macrophage transformation into foam cells during the atherosclerotic process. The therapeutic significance of adenosine-mediated effects is highlighted.

ADENOSINE RECEPTORS

Adenosine is an endogenous purine nucleoside signaling molecule that is constitutively present at low levels in the extracellular space. Adenosine concentrations dramatically increase following metabolic stress conditions at sites of tissue injury and inflammation such as those induced by hypoxia or ischemia.7–9 Adenosine is a regulatory metabolite and the biological activities of adenosine are mediated throughinteraction with four distinct G protein–coupled cell surface receptors classified by molecular, biochemical and pharmacological data into four subtypes: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3.10, 11 The A1and A3 receptors couple with inhibitory Gi proteins and inhibit adenylate cyclase, diminishing cellular cAMP levels. In contrast, A2A and A2B receptors, couple to stimulatory Gs proteins and activate adenylate cyclase, leading to an increase in intracellular cAMP levels. These subtypes elicit unique and sometimes opposing effects.

ATHEROSCLEROTIC PLAQUE AND FOAM CELLS

The development of an atherosclerotic plaque begins with the recruitment of blood-borne inflammatory monocytes to activated vascular endothelium at sites of lipid deposition or arterial injury.12–14 Circulating monocytes adhere to the endothelial layer, then, in response to locally produced chemoattractant molecules, transmigrate across the endothelium into the intima where they differentiate into macrophages.15 These macrophages then express scavenger receptors that bind and facilitate uptake of modified lipoproteins. Through the ingestion of these subendothelial lipoproteins, the macrophages hoard large amounts of intracellular cholesterol and thereby form foam cells. Accumulation of foam cells leads to the fatty streak- the first macroscopically recognizable lesion of atherosclerosis.16 The fatty streak progressively evolves to an advanced plaque with characteristic architecture and complex cellular composition. The plaque consists generally of a lipid-rich necrotic core bordered by a rim of lipid-laden macrophages, and covered by a fibrous cap composed of smooth muscle cells and collagen.17

CHOLESTEROL TRANSPORT DISRUPTION AND MACROPHAGE CHOLESTEROL OVERLOAD

Formation of foam cells by cholesterol accumulation in arterial wall macrophages is a crucial first step in atherogenesis. A number of critical proteins are involved in maintaining a balance between influx and efflux of lipids from macrophages. This balance depends upon limiting cholesterol inflow through scavenger receptors as well as maintaining outflow through reverse cholesterol transport – the transport of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues, including cholesterol-laden macrophages in vessel walls, to the liver for excretion.18,19 A number of cellular proteins work in a coordinated fashion to accomplish reverse cholesterol transport. These include cytochrome P450 cholesterol 27-hydroxylase, ATP binding cassette transporters (ABC) A1 and ABCG1, and liver X receptors (LXRα and LXRβ).20–22

Low density lipoprotein (LDL) is poorly taken up by macrophages unless it has been modified, because macrophages contain only one native LDL receptor that is subject to feedback mechanisms. However, macrophages express a number of scavenger receptors. The scavenger receptor family proteins are defined by their ability to bind and internalize modified lipoproteins, primarily oxidized LDL, contributing to foam cell formation. Once oxidized, LDL particles lose their affinity for the LDL receptor but gain affinity for scavenger receptors and can then be taken up by intimal macrophages. The class B scavenger receptor, CD36, is a glycoprotein that mediates the uptake of oxidized LDL particles by macrophages.23 The class A scavenger receptors (SR-A) are widely expressed on macrophages, but can also be detected on endothelial and smooth muscle tissues. SR-AI and SR-AII isoforms recognize a wide variety of polyanionic ligands. They can both bind modified LDL, both acetylated and oxidized, as well as polynucleic acids, phosphatidyl serine and bacterial components.24 In human atherosclerotic lesions, SR-A is expressed on the cell surface of macrophages and macrophage-derived foam cells. SR-A deficient mice crossbred onto an apolipoprotein E (apoE) knockout background exhibit a 60% reduction in atherosclerosis in the aortic root.25 In hyperlipidemic adult mice, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated silencing of either SR-A or CD36 reduces atherosclerotic lesion size.26

Homeostatic atheroprotective mechanisms that orchestrate cholesterol balance in the vessel wall involve reverse cholesterol transport from arterial wall to liver. Cholesterol 27-hydroxylase enzyme activity is crucial in this pathway responsible for efflux of cholesterol from cells. This enzyme constitutes one of the first lines of defense in the prevention of atherosclerosis.22 Cholesterol 27-hydroxylase catalyzes the initial step in the oxidation of the side chain of sterol intermediates in the bile acid synthesis pathway: 27-hydroxylation of cholesterol to form 27-hydroxycholesterol. 27-Hydroxycholesterol, the most abundant oxysterol in human circulation (0.4 μM in normal serum), is a component of the major circulating lipoproteins. It is transported out of cells through lipid membranes orders of magnitude faster than cholesterol.27 Cholesterol 27-hydroxylase activity in arterial endothelium and macrophages provides a pathway for elimination of intracellular cholesterol by conversion to more polar metabolites, including 27-hydroxycholesterol, that are transported to the liver for excretion.28 27-Hydroxycholesterol behaves like a statin, potently inhibiting HMG CoA reductase while also suppressing smooth muscle cell proliferation and diminishing macrophage foam cell formation.22,29

ABCA1 plays an essential role in the prevention of foam cell formation in macrophages by mediating the active export of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids to apoA1, the major lipoprotein in high density lipoprotein (HDL).30,31 ABCA1 thus functions as a regulator of HDL plasma concentration.32 Under conditions where expression levels of reverse cholesterol transport genes are low, macrophages display a reduced capacity to handle and efflux cellular cholesterol. In atherosclerosis-prone mice, either apoE-deficient or LDL receptor-deficient, selective inactivation of ABCA1 in monocytes/macrophages markedly increased atherosclerosis and foam cell accumulation.33,34

Macrophage cholesterol efflux mechanisms and expression of a number of ABC transporters lie under the transcriptional control of LXRs.35 LXRs function as sterol sensors by responding to increases in oxysterols with upregulated transcription of gene products that control cholesterol catabolism and efflux.36 Activation of LXRs by endogenous oxysterol ligands induces transcription of ABCA1 and ABCG1.37 Oxysterols bind directly to the ligand binding domain of LXRs.38 27-Hydroxycholesterol, the most abundant enzymatically generated oxysterol in human atheroma, is an endogenous LXR ligand. Thus, 27-hydroxycholesterol represents not only a cholesterol efflux pathway from macrophages, it also induces ABC transporter expression and subsequent HDL-dependent efflux via the activation of LXR (Figure 1).

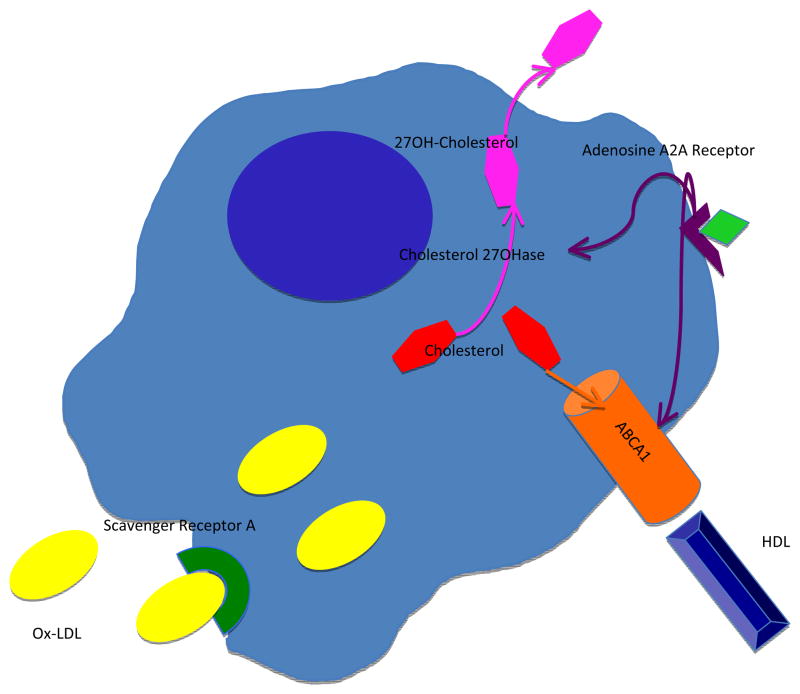

Figure 1. Macrophage cholesterol transport pathways modulated by A2AR activation.

Ligation of the A2AR induces expression of the mitochondrial cytochrome P450 27-hydroxylase (27OH) which produces the oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol (27OH-cholesterol). 27-hydroxycholesterol is hydrophilic and exits the cell more readily than cholesterol. A2AR occupancy stimulates increased reverse cholesterol transport via ABCA1. 27-hydroxycholesterol also enhances ABCA1 expression through LXR. Lipidation of apoA-I by the ABCA1 pathway is required for generating HDL particles and clearing sterols from macrophages. The scavenger receptor LOX-1 facilitates the uptake of oxidized LDL. A2AR ligation prevents cytokine-mediated upregulation of LOX-1.

ADENOSINE EFFECTS ON CHOLESTEROL EFFLUX PATHWAYS

Recently, considerable progress has been made in understanding the molecular basis of lipoprotein metabolism, including the influence of adenosine. Knowledge of adenosine effects began with the observation that methotrexate, an effective treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other forms of inflammatory arthritis, increases extracellular adenosine concentrations.39 Autoimmune disorders such as RA accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis.40 Methotrexate is the most frequent choice of disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy for RA. Methotrexate may provide a substantial survival benefit in RA, largely by reducing cardiovascular mortality.41 Many of the anti-inflammatory effects of methotrexate are attributed to adenosine release.42 Anti-atherogenic effects of methotrexate may be mediated through adenosine as well. Adenosine acts as an anti-inflammatory agent, suppressing expression of inflammatory cytokines.43 Anti-inflammatory effects of adenosine on leukocytes and endothelial cells are mediated through its A2A receptor. Studies have suggested that occupancy of the anti-inflammatory adenosine A2A receptor minimizes early atherosclerotic changes in arteries following injury.44

Monocytes/macrophages have recently emerged as prime targets of the immunomodulatory impact of adenosine. Our laboratory has determined that A2A receptor occupancy affects expression of proteins involved in cholesterol flux in monocytes/macrophages and, consequently, provides a defense against lipid overload-induced macrophage foam cell formation.45 In BALB/c murine macrophages, a selective A2A receptor agonist increases 27-hydroxylase message by 47%. In murine macrophages lipid-loaded with acetylated LDL, A2A receptor occupancy modulates foam cell formation stimulated by either immune complexes (bovine serum albumin- rabbit anti-bovine serum albumin) or the cytokine IFN-γ. Macrophages are activated by IFN-γ, a proinflammatory and proatherogenic cytokine.46 The selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS-21680 completely abrogates immune complex-induced foam cell transformation in BALB/c peritoneal macrophages. Pre-incubation with the A2A receptor antagonist ZM-241385 reverses this effect, allowing foam cell formation to proceed as if no agonist were present. Similar results are observed in murine peritoneal macrophages from A3 receptor knockout mice and their respective wild-type controls. In contrast, CGS-21680 fails to impact immune complex-stimulated foam cell transformation in peritoneal macrophages from A2A receptor knockout mice. This shows a direct physiologic link between macrophage A2A receptor ligation and the ability of the cells to defend against cholesterol overload.

Based on the observations in murine cells, our group proceeded to establish the same effect in THP-1 human monocytoid cells. THP-1 cells display macrophage like differentiation in response to phorbol esters and are a frequently used model system for macrophage behavior in atherosclerosis.47,48 THP-1 cells express adenosine receptors, including the A2A receptor and incubation of lipid-loaded THP-1 macrophages with CGS-21680 (1μM) diminishes foam cell transformation stimulated by IFN-γ by 30% and reduces immune complex-stimulated foam cell transformation by approximately 40%.45,49,50

In THP-1 monocytes, A2A receptor ligation with CGS-21680 increases cholesterol 27-hydroxylase and ABCA1 mRNA expression levels in concert (Figure 1). When exposed to CGS-21680 in the presence and absence of the antagonist ZM-241385, both cholesterol 27-hydroxylase and ABCA1 message levels fail to rise. Similarly, in THP-1 macrophages exposed to IFN-γ, addition of CGS-21680 increases ABCA1 protein levels. As might be expected, in THP-1-derived macrophages subjected to siRNA for knockdown of ABCA1, A2A receptor activation has no effect on ABCA1 protein levels. Further, CGS-21680 fails to decrease foam cell formation in IFN-γ-treated THP-1 macrophages with silencing of ABCA1. In parallel experiments with ABCG1, A2A receptor activation does not alter expression or function of this transporter. Thus, A2A-induced effects on macrophage foam cell transformation can be attributed to a mechanism that involves ABCA1.51

Our group then went on to demonstrate the in vitro ability of methotrexate to prevent IFN-γ-induced transformation of lipid-laden macrophages into foam cells, an effect mediated by promotion of reverse cholesterol transport by methotrexate.52

To make certain that THP-1 results accurately represent primary human monocyte behavior, PBMC were isolated from healthy human donors and incubated for 24 hours in media with and without the addition of methotrexate (5 μM). Methotrexate exposure resulted in a nearly fourfold increase in 27-hydroxylase mRNA as assessed by QRT-PCR.

This atheroprotective effect of methotrexate, mediated by adenosine acting through A2A receptor activation, may account for the beneficial effects of methotrexate therapy in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in RA.53

ADENOSINE EFFECTS ON THE LOX-1 RECEPTOR

Studies in animals and humans have shown that maintenance of the functional integrity of the endothelium exerts potent antiatherosclerotic and antithrombotic effects. Hypercholesterolemia causes focal activation of endothelium in large and medium-sized arteries. Atherosclerosis is initiated by dysfunction of endothelial cells at lesion-prone sites in the walls of arteries. The endothelium becomes activated and leaky which results in extravasation of plasma molecules and lipoprotein particles as well as monocyte infiltration into the arterial intima.54 The endothelial receptor for oxidized LDL called the lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1) is a membrane bound receptor that is found at high concentrations in human atherosclerotic lesions.55,56 LOX-1, a member of the scavenger receptor family, is expressed in vivo in vascular endothelium, macrophages and smooth muscle cells.57–59 It acts as a cell surface endocytosis receptor.60 It binds, internalizes, and degrades oxidized LDL but not native LDL or acetylated LDL.61 LOX-1 mRNA is expressed in atheromatous lesions.62,63 This receptor is involved in the pathobiological pro-atherogenic actions of oxidized LDL in the endothelium such as induction of adhesion molecules, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and growth factors and activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB (NFkB).64 LOX-1 gene expression in endothelial cells and macrophages is upregulated markedly by TNF-α.58,65 The LOX-1 receptor may play an important role in oxidized LDL uptake and subsequent foam cell formation in macrophages. Activation of LOX-1 elicits rapid generation of reactive oxygen species and decreases nitric oxide release from endothelial cells, both of which contribute to endothelial dysfunction and vascular damage.64,66 Recent studies in our lab have demonstrated downregulation of LOX-1 in both cultured human arterial endothelium and THP-1 macrophages upon adenosine A2A receptor ligation. The effect is completely abolished by pretreatment with an A2A receptor antagonist (unpublished results).

HYPOXIA-INDUCIBLE FACTOR-1 (HIF-1)

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is a principal transcriptional regulator of angiogenesis and is also involved in inflammatory reactions. HIF-1 is a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of α and β subunits.67 HIF-1β is constitutively expressed in many cell types. HIF-1α is undetectable under normoxia because rapid proteasomal degradation renders it highly labile. However, under hypoxic conditions it is stabilized due to the inhibition of proline hydroxylation and subsequent decreases in ubiquitination and degradation.68 Hypoxia has been detected in human atherosclerotic lesions and HIF-1 colocalizes with macrophages in areas of hypoxia where it has been shown to promote intraplaque angiogenesis and foam cell development.69 In the human monoblastic cell line (U937), transfection of HIF-1α-siRNA inhibits foam cell formation in the presence of oxidized LDL.70 Under conditions of normal oxygen tension, adenosine induces HIF-1 and the expression of HIF-1 target genes in macrophages via activation of the adenosine A2A receptor. HIF-1 activation occurs through the protein kinase C and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K/Akt) pathways.71 Under hypoxic conditions, adenosine increases accumulation of HIF-1 in U937 cells, human macrophages and lipid-loaded foam cells.72 This effect is not due to changes in HIF-1 transcription or stability, but is likely a result of increased translation. Blockade of each specific adenosine receptor (selective for A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) individually or silencing of each receptor reduces HIF-1α protein accumulation in the presence of adenosine. Simultaneous silencing of all 4 adenosine receptors eliminates the adenosine effect while high affinity agonists for individual adenosine receptors increase HIF-1 protein. This suggests that all adenosine receptors contribute to HIF-1 enhancement by adenosine. HIF-1 modulation involves extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) and protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation in the case of A1, A2A, A2B and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation in the case of A3 receptors. In this study, foam cell formation was enhanced by adenosine through activation of A2B and A3 subtypes. The authors posit that A3, A2B or mixed A3/A2B antagonists may provide potential therapeutic approaches for blocking important steps in atherosclerotic plaque development.

ADENOSINE COUNTERS ATHEROGENIC EFFECTS OF CYCLO-OXYGENASE INHIBITORS

Cyclooxygenase (COX), a key enzyme required for the synthesis of prostaglandins, plays an important role in inflammatory processes (Figure 2). COX exists in two distinct isoforms, COX1 (constitutive form, present in stomach, intestines, kidneys, and platelets) and COX2 (inducible form expressed under pathological conditions such as inflammation). Inhibitors of COX such as traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or tNSAIDs inhibit both COX1 and COX2 while selective COX-2 inhibitors or coxibs have good tolerability and therapeutic activity, but may contribute to or promote cardiovascular toxicity.73 The cardiovascular risk of coxibs has led to withdrawal from the market of a number of the drugs in this class. Only celecoxib is available for clinical use at this time. The precise mechanisms by which COX inhibitors amplify cardiovascular risk are unclear. A recently uncovered biological rationale for this problem is the discovery that COX inhibition promotes atherogenesis by both compromising cholesterol outflow and enhancing cholesterol uptake in macrophages.74,75 Inhibition of COX activity in human monocytes/macrophages interferes with cellular defense against cholesterol overload by diminishing expression of cholesterol 27-hydroxylase and ABCA1, proteins responsible for reverse cholesterol transport out of the cell to the circulation for ultimate excretion.76 COX inhibition also triggers over-expression of scavenger receptors CD36 and ScR-A, leading to uncontrolled uptake of modified cholesterol. The result is excessive macrophage foam cell transformation.

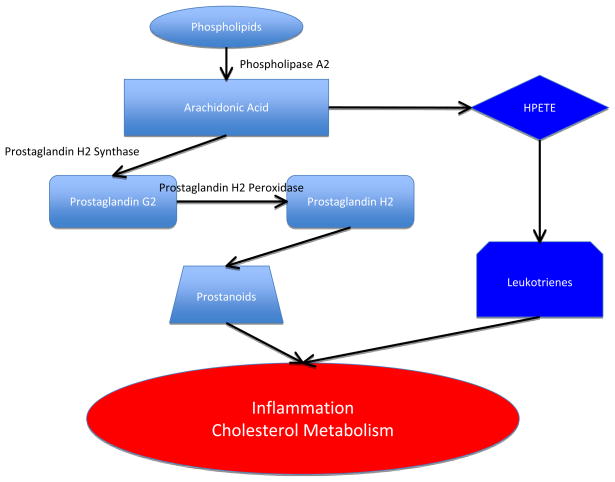

Figure 2. The COX pathway supports normal cholesterol transport.

Free arachidonic acid is produced in tissues from membrane phospholipids by the enzyme phospholipase A2. Arachidonic acid can be metabolized via either the COX pathway, which produces prostaglandin H2 or via the lipoxygenase pathway, which produces 5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoate (HPETE), the starting point for synthesis of leukotrienes. COX has two activities: endoperoxide synthase activity that oxygenates and cyclizes the arachidonic acid to form the cyclic peroxide prostaglandin G2, and peroxidase activity that converts prostaglandin G2 to prostaglandin H2. Prostaglandin H2 then serves as the substrate for enzymatic pathways that produce prostanoids (prostaglandins, thromboxanes and prostacyclins). Prostaglandin products of the COX pathway are involved in signaling events in the inflammatory response, but are also necessary for maintenance of cholesterol homeostasis. COX or phospholipase A2 inhibition results in decreased production of reverse cholesterol transport proteins and increased foam cell formation. Adenosine A2A receptor agonists counter effects of COX inhibition and restore efflux pathways.

Activation of the adenosine A2A receptor by either the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug methotrexate or an A2A-specific agonist counters the effect of COX inhibition. The specific A2A agonist CGS-21680 overcomes the reduction in both 27-hydroxylase and ABCA1 expression induced by the COX-2 inhibitor NS398. Addition of CGS-21680 to NS398 (50μM)-treated THP-1 cells gives rise to a 184% increase in 27-hydroxylase and a 141% increase in ABCA1 expression.

In THP-1 cells, methotrexate (5μM, 18hrs) increases 27-hydroxylase mRNA expression and completely blocks NS398 (50μM)-induced downregulation of 27-hydroxylase enzyme expression. Methotrexate also prevents NS398 and IFN-γ (500U/ml) from increasing transformation of lipid-loaded THP-1 macrophages into foam cells. Our results suggest that methotrexate reduces death rates due to ASCVD, at least in part, by favorably altering cholesterol homeostasis.52

OTHER ACTIONS RELEVANT TO ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Although adenosine A2A receptor ligation has a suppressive effect on inflammation and foam cell formation, multiple other factors are involved in atherosclerotic lesion development and several of these may be impacted by adenosine. For example, adenosine may modify vascular tone and play a role in vasculogenesis/angiogenesis and vascular remodeling.77,78 Adenosine A2A receptor activation stimulates production of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor while also inhibiting production of thrombospondin 1, an antiangiogenic protein.79 The building of new blood vessels may be a reparative mechanism to restore blood flow and oxygen to affected tissue. The A2A receptor exerts potent coronary vasodilatory effects and the A2B receptor may also be vasodilatory to a lesser extent.80–82 Adenosine may promote tumor survival by stimulating angiogenesis.83 Another mechanism by which adenosine encourages tumor growth is through inhibition of antitumor T cells via the A2A receptor. 84

In addition to anti-inflammatory effects of the A2A receptor, the A2B receptor also influences inflammatory processes. In mice with targeted deletion of the A2B gene, expression of cytokines is elevated and leukocyte adhesion to the vasculature is significantly increased.85

The A2A receptor subtype is of critical importance in stroke. Inactivation of this receptor or administering antagonists has been shown to offer robust protection against brain injury in models of stroke in gerbils and rats. 86,87 Adenosine can also be neuroprotective in ischemic and 88 hypoxic brain injury, primarily by acting through A1 receptors.89

In the murine heart, A1 receptor activation improves postischemic contractile recovery. Studies performed in animal models indicate that adenosine receptor activation is involved in the cardioprotection conferred by postconditioning (repetitive interruptions in blood flow applied early in reperfusion).90 The protective effects are blocked by A2A and A3 selective antagonists given before postconditioning. Intravenous adenosine has been used as a postconditioning drug to protect the human heart and minimize infarct size during acute myocardial infarct reperfusion therapy.91

ATHEROSCLEROSIS IN A2A RECEPTOR DEFICIENT ATHEROSCLEROSIS-PRONE MICE

Wang et al92 crossed the well-described apoE knockout mouse (a hypercholesterolemic mouse that develops complex atherosclerotic lesions) with an adenosine A2A receptor knockout mouse to generate the double knockout. Unexpectedly, suppression of atherosclerosis was observed in this double knockout with a reduced number of macrophages in the atherosclerotic lesions compared to apoE deficient single knockout mice. This was attributed to apoptosis of macrophages and foam cells due to increased p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase (MAPK) activity in the A2A receptor knockout mice. This study stands in contrast to multiple findings consistent with atheroprotective effects of the A2A receptor and may represents an artifact of the extreme inability to export cholesterol from macrophages in this double knockout mouse.

Firm conclusions cannot be drawn regarding a definitive role for adenosine in atherosclerosis at this time, even through a suppressive effect of adenosine on inflammation and foam cell formation has been observed.

CONCLUSIONS

The transformation of macrophages to foam cells is a critical component of atherosclerotic lesion formation.93 Reverse cholesterol transport proteins work in a coordinated fashion to export excess lipid from macrophages, limiting foam cell formation.

The endogenous purine nucleoside adenosine is widely thought to elicit coronary vasodilation and attenuate smooth muscle cell proliferation, thereby providing cardioprotection. Adenosine released into the extracellular space during tissue stress and injury can regulate macrophage inflammatory and atherogenic functions through ligation of one or more plasmalemmal adenosine receptor subtypes.

Potent anti-atherosclerotic effects of A2A receptor stimulation include inhibition of macrophage foam cell transformation and upregulation of the reverse cholesterol transport proteins cholesterol 27-hydroxylase and ABCA1. Crosstalk among adenosine receptors has been documented. In nerve terminals of young adult rats, activation of adenosine A2A receptors decreases presynaptic adenosine A1 receptor binding.94 Adenosine receptor subtype interactions may also occur in the heart. Cardiac adenosine A2A receptors influence the adenosine A1 receptor anti-adrenergic effect.95,96 Further studies are needed to establish whether interaction among adenosine receptor subtypes plays a role in determining extent of foam cell formation.

Future research may reveal new pathways involved in cholesterol transport and should provide novel therapeutic agents for cardiovascular disease. Thus, adenosine and some of its analogs that bind to the A2A receptor on monocytes/macrophages may offer an alternative therapeutic approach to lower risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants AR56672, AR56672S1, and AR54897, and the NYU-HHC Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1RR029893). (Cronstein) and by an Innovative Research Grant from the Arthritis Foundation, National Center and a Winthrop Research Institute Pilot and Feasibility Grant (Reiss).

References

- 1.Delyani JA, Van Wylen DGL. Endocardial and epicardial interstitial purines and lactate during graded ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1019–H1026. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.3.H1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntosh VJ, Lasley RD. Adenosine receptor-mediated cardioprotection: are all 4 subtypes required or redundant? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Feb 18; doi: 10.1177/1074248410396877. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnholt KE, Kota RS, Aung HH, Rutledge JC. Adenosine blocks IFN-gamma-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 on serine 727 to reduce macrophage activation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6767–6777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leon ML, Zuckerman SH. Gamma interferon: a central mediator in atherosclerosis. Inflamm Res. 2005;54:395–411. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-1377-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiss AB, Hammerschlag MR, Awadallah NW, Roblin PM, Chan ESL, Cronstein BN. Immune modulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Recent Research Devel in Protein Engineering. 2001;1:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox AC, Reed GE, Meilman H, Silk BB. Release of nucleosides from canine and human hearts as an index of prior ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 1979;43:52–58. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berne RM, Belardinelli L. Effects of hypoxia and ischaemia on coronary vascular resistance, A-V node conduction and S-A node excitation. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1985;694:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb08795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WL, Thomas RA, Berne RM, Rubio R. Adenosine production in the ischemic kidney. Circ Res. 1978;43:390–397. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasko G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: An endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis. the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiss AB, Glass AD. Atherosclerosis: immune and inflammatory aspects. J Investig Med. 2006;54:123–131. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.05051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennings M, Meurs I, Ye D, Out R, Hoekstra M, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Regulation of cholesterol homeostasis in macrophages and consequences for atherosclerotic lesion development. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5588–5596. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S, Guyton JR, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schaffer SA, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1994;89:2462–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Weber DK, Kutys R, Finn AV, Gold HK. Pathologic assessment of the vulnerable human coronary plaque. Heart. 2004;90:1385–1391. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.041798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephen SL, Freestone K, Dunn S, Twigg MW, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Walker JH, Wheatcroft SB, Ponnambalam S. Scavenger receptors and their potential as therapeutic targets in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Int J Hypertens. 2010;2010:646929. doi: 10.4061/2010/646929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Velde AE. Reverse cholesterol transport: from classical view to new insights. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5908–5915. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im SS, Osborne TF. Liver x receptors in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Circ Res. 2011;108:996–1001. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voloshyna I, Reiss AB. The ABC transporters in lipid flux and atherosclerosis. Prog Lipid Res. 2011;50:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiss AB, Awadallah NW, Cronstein BN. Cytochrome P450 cholesterol 27-hydroxylase: An anti-atherogenic enzyme. Rec Res Devel Lipid Res. 2000;4:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. CD36 and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:483–491. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200010000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhaliwal BS, Steinbrecher UP. Scavenger receptors and oxidized low density lipoproteins. Clin Chim Acta. 1999;286:191–205. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(99)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, Takashima Y, Kawabe Y, Cynshi O, Wada Y, Honda M, Kurihara H, Aburatani H, Doi T, Matsumoto A, Azuma S, Noda T, Toyoda Y, Itakura H, Yazaki Y, Horiuchi S, Takahashi K, Kruijt JK, van Berkel TJC, Steinbrecher UP, Ishibashi S, Maeda N, Gordon S, Kodama T. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386:292–296. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mäkinen PI, Lappalainen JP, Heinonen SE, Leppänen P, Lähteenvuo MT, Aarnio JV, Heikkilä J, Turunen MP, Ylä-Herttuala S. Silencing of either SR-A or CD36 reduces atherosclerosis in hyperlipidaemic mice and reveals reciprocal upregulation of these receptors. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:530–538. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dzeletovic S, Breuer O, Lund E, Diczfalusy U. Determination of cholesterol oxidation products in human plasma by isotope dilution-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1995;225:73–80. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babiker A, Andersson O, Lund E, Xiu R, Deeb S, Reshef A, Leitersdorf E, Diczfalusy U, Bjorkhem I. Elimination of cholesterol in macrophages and endothelial cells by the sterol 27-hydroxylase mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26253–26261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroepfer GJ., Jr Oxysterols: modulators of cholesterol metabolism and other processes. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:361–554. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawn RM, Wade DP, Garvin MR, Wang X, Schwartz K, Porter JG, Seilhamer JJ, Vaughan AM, Oram JF. The Tangier disease gene product ABC1 controls the cellular apolipoprotein-mediated lipid removal pathway. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:R25–R31. doi: 10.1172/JCI8119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oram JF, Vaughan AM. ATP-binding cassette cholesterol transporters and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:1031–1043. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250171.54048.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wade DP, Owen JS. Regulation of the cholesterol efflux gene, ABCA1. Lancet. 2001;357:161–163. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aiello RJ, Brees D, Bourassa PA, Royer L, Lindsey S, Coskran T, Haghpassand M, Francone OL. Increased atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice with inactivation of ABCA1 in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:630–637. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000014804.35824.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Eck M, Bos IS, Kaminski WE, Orsó E, Rothe G, Twisk J, Böttcher A, Van Amersfoort ES, Christiansen-Weber TA, Fung-Leung WP, Van Berkel TJ, Schmitz G. Leukocyte ABCA1 controls susceptibility to atherosclerosis and macrophage recruitment into tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6298–6303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092327399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkateswaran A, Lafitte BA, Joseph SB, Mak PA, Wilpitz DC, Edwards PA, Tontonoz P. Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12097–12102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu X, Menke JG, Chen Y, Zhou G, MacNaul KL, Wright SD, Sparrow CP, Lund EG. 27-Hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous ligand for LXR in cholesterol-loaded cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38378–38387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:607–614. doi: 10.1172/JCI27883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janowski BA, Grogan MJ, Jones SA, Wisely GB, Kliewer SA, Corey EJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRα and LXRβ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cronstein BN. Low-dose methotrexate: a mainstay in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:163–172. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Martin J. Rheumatoid arthritis: a disease associated with accelerated atherogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cronstein BN, Naime D, Ostad E. The antiinflammatory effects of methotrexate are mediated by adenosine. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;370:411–416. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2584-4_89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasko G, Pacher P, Deitch EA, Vizi ES. Shaping of monocyte and macrophage function by adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McPherson JA, Barringhaus KG, Bishop GG, Sanders JM, Rieger JM, Hesselbacher SE, Gimple LW, Powers ER, Macdonald T, Sullivan G, Linden J, Sarembock IJ. Adenosine A(2A) receptor stimulation reduces inflammation and neointimal growth in a murine carotid ligation model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:791–796. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reiss AB, Rahman MM, Chan ESL, Montesinos MC, Awadallah NW, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor occupancy stimulates expression of proteins involved in reverse cholesterol transport and inhibits foam cell formation in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:727–734. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: pathogenic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:515–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larigauderie GF, Christophe JM, Lasselin C, Copin C, Fruchart J-C, Castro G, Rouis M. Adipophilin enhances lipid accumulation and prevents lipid efflux from THP-1 macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:504–510. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000115638.27381.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fach EM, Garulacan LA, Gao J, Xiao Q, Storm SM, Dubaquie YP, Hefta SA, Opiteck GJ. In vitro biomarker discovery for atherosclerosis by proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1200–1210. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400160-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khoa ND, Montesinos MC, Reiss AB, Delano D, Awadallah N, Cronstein BN. Inflammatory cytokines regulate function and expression of adenosine A(2A) receptors in human monocytic THP-1 cells. J Immunol. 2001;16:4026–4032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bshesh K, Zhao B, Spight D, Biaggioni I, Feokistov I, Denenberg A, Wong HR, Shanley TP. The A2A receptor mediates an endogenous regulatory pathway of cytokine expression in THP-1 cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:1027–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bingham TC, Cronstein BN, Fisher EA, Parathath S, Reiss A, Chan E. A2A adenosine receptor stimulation decreases foam cell formation by enhancing ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:683–690. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0709513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reiss AB, Carsons SE, Anwar K, Rao S, Edelman SD, Zhang H, Fernandez P, Cronstein BN, Chan ES. Atheroprotective effects of methotrexate on reverse cholesterol transport proteins and foam cell transformation in human THP-1 monocyte/macrophages. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3675–3683. doi: 10.1002/art.24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coomes E, Chan ES, Reiss AB. Methotrexate in Atherogenesis and Cholesterol Metabolism. Cholesterol. 2011;2011:503028. doi: 10.1155/2011/503028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2007;115:1285–1295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawamura T, Masaki T, Hashimoto N, Kita T. Expression of lectin oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 in human atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 1999;99:3110–3117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehta JL, Chen J, Hermonat PL, Romeo F, Novelli G. Lectin-like, oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1): a critical player in the development of atherosclerosis and related disorders. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehta JL, Li DY. Identification and autoregulation of receptors for Ox-LDL in cultured human coronary artery endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:511–514. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kume N, Moriwaki H, Kataoka H, Minami M, Murase T, Sawamura T, Masaki T, Kita T. Inducible expression of LOX-1, a novel receptor for oxidized LDL, in macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;902:323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kataoka H, Kume N, Miyamoto S. Oxidized LDL modulates Bax/Bcl-2 through the lectin-like Ox-LDL receptor-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:955–960. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reiss AB, Anwar K, Wirkowski P. Lectin-like oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1 (LOX-1) in atherogenesis: a brief review. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:2641–2652. doi: 10.2174/092986709788681994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sawamura T, Kume N, Aoyama T, Moriwaki H, Hoshikawa H, Aiba Y, Tanaka T, Miwa S, Katsura Y, Kita T, Masaki T. An endothelial receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Nature. 1997;386:73–77. doi: 10.1038/386073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kataoka H, Kume N, Miyamoto S, Minami M, Moriwaki H, Murase T, Sawamura T, Masaki T, Hashimoto N, Kita T. Expression of lectinlike oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 in human atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 1999;99:3110–3117. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen CH, Jiang W, Via DP, Luo S, Li TR, Lee YT, Henry PD. Oxidized low-density lipoproteins inhibit endothelial cell proliferation by suppressing basic fibroblast growth factor expression. Circulation. 2000;101:171–177. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunn S, Vohra RS, Murphy JE, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Walker JH, Ponnambalam S. The lectin-like oxidized low-density-lipoprotein receptor: a pro-inflammatory factor in vascular disease. Biochem J. 2008;409:349–355. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kume N, Sawamura T, Moriwaki H, Itokawa S, Hoshikawa H, Aoyama A, Nishi E, Ueno Y, Masaki T, Kita T. Inducible expression of LOX-1, a novel lectin-like receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein, in vascular endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1998;83:322–327. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pirillo A, Reduzzi A, Ferri N, Kuhn H, Corsini A, Catapano AL. Upregulation of lectine-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1) by 15-lipoxygenase-modified LDL in endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1230–1237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishi K, Oda T, Takabuchi S, Oda S, Fukuda K, Adachi T, Semenza GL, Shingu K, Hirota K. LPS induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation in macrophage-differentiated cells in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:983–995. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sluimer JC, Gasc JM, van Wanroij JL, Kisters N, Groeneweg M, Sollewijn Gelpke MD, Cleutjens JP, van den Akker LH, Corvol P, Wouters BG, Daemen MJ, Bijnens AP. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible transcription factor, and macrophages in human atherosclerotic plaques are correlated with intraplaque angiogenesis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang G, Li T, Qiu Y, Rui Y, Chen W, Lou Y. RNA interference for HIF-1alpha inhibits foam cells formation in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;562:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Ponti C, Carini R, Alchera E, Nitti MP, Locati M, Albano E, Cairo G, Tacchini L. Adenosine A2a receptor-mediated, normoxic induction of HIF-1 through PKC and PI-3K- dependent pathways in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:392–402. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0107060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gessi S, Fogli E, Sacchetto V, Merighi S, Varani K, Preti D, Leung E, Maclennan S, Borea PA. Adenosine modulates HIF-1{alpha}, VEGF, IL-8, and foam cell formation in a human model of hypoxic foam cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:90–97. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patrono C, Roca B. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: past, present and future. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reiss AB, Anwar F, Chan ESL, Anwar K. Disruption of cholesterol efflux by coxib medications and inflammatory processes: link to increased cardiovascular risk. J Invest Med. 2009;57:695–702. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31819ec3c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anwar K, Voloshyna I, Littlefield MJ, Carsons SE, Wirkowski PA, Jaber NL, Sohn A, Eapen S, Reiss AB. COX-2 inhibition and inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A2 increase CD36 expression and foam cell formation in THP-1 cells. Lipids. 2011;46:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chan ESL, Zhang H, Fernandez P, Edelman SD, Pillinger MH, Ragolia L, Palaia T, Carsons SE, Reiss AB. Effect of COX inhibition on cholesterol efflux proteins and atheromatous foam cell transformation in THP-1 human macrophages: A possible mechanism for increased cardiovascular risk. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R4. doi: 10.1186/ar2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Clark AN, Youkey R, Liu X, Jia L, Blatt R, Day YJ, Sullivan GW, Linden J, Tucker AL. A1 Adenosine receptor activation promotes angiogenesis and release of VEGF from monocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:1130–1138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Auchampach A. Adenosine receptors and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101:1075–1077. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Desai A, Victor-Vega C, Gadangi S, Montesinos MC, Chu CC, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor stimulation increases angiogenesis by down-regulating production of the antiangiogenic matrix protein thrombospondin 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1406–1413. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Snowdy S, Zhang Y, Monopoli A, Lozza G, Ongini E, Olsson RA, Dennis DM. The A2A adenosine receptor mediates coronary vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teng B, Ledent C, Mustafa SJ. Up-regulation of A2B adenosine receptor in A2A adenosine receptor knockout mouse coronary artery. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:905–914. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berwick ZC, Payne GA, Lynch B, Dick GM, Sturek M, Tune JD. Contribution of adenosine A(2A) and A(2B) receptors to ischemic coronary dilation: role of K(V) and K(ATP) channels. Microcirculation. 2010;17:600–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Olah ME, Caldwell CC. Adenosine receptors and mammalian toll-like receptors: synergism in macrophages. Mol Interv. 2003:370–374. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.7.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ohta A, Gorelik E, Prasad SJ, Ronchese F, Lukashev D, Wong MK, Huang X, Caldwell S, Liu K, Smith P, Chen JF, Jackson EK, Apasov S, Abrams S, Sitkovsky M. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang D, Zhang Y, Nguyen HG, Koupenova M, Chauhan AK, Makitalo M, Jones MR, St Hilaire C, Seldin DC, Toselli P, Lamperti E, Schreiber BM, Gavras H, Wagner DD, Ravid K. The A2B adenosine receptor protects against inflammation and excessive vascular adhesion. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1913–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI27933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Von Lubitz DK, Lin RC, Jacobson KA. Cerebral ischemia in gerbils: effects of acute and chronic treatment with adenosine A2A receptor agonist and antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;287:295–302. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00498-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Monopoli A, Lozza G, Forlani A, Mattavelli A, Ongini E. Blockade of adenosine A2A receptors by SCH 58261 results in neuroprotective effects in cerebral ischaemia in rats. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3955–3959. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cunha RA. Neuroprotection by adenosine in the brain: from A(1) receptor activation to A (2A) receptor blockade. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:111–134. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-0649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peart J, Headrick JP. Intrinsic A1 adenosine receptor activation during ischemia or reperfusion improves recovery in mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2166–H2175. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kin H, Zatta AJ, Lofye MT, Amerson BS, Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Zhao ZQ, Guyton RA, Headrick JP, Vinten-Johansen J. Postconditioning reduces infarct size via adenosine receptor activation by endogenous adenosine. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mahaffey KW, Puma JA, Barbagelata NA, DiCarli MF, Leesar MA, Browne KF, Eisenberg PR, Bolli R, Casas AC, Molina-Viamonte V, Orlandi C, Blevins R, Gibbons RJ, Califf RM, Granger CB. Adenosine as an adjunct to thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial: the Acute Myocardial Infarction STudy of ADenosine (AMISTAD) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1711–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang H, Zhang W, Zhu C, Bucher C, Blazar BR, Zhang C, Chen JF, Linden J, Wu C, Huo Y. Inactivation of the adenosine A2A receptor protects apolipoprotein E-deficient mice from atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1046–1052. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.188839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lopes LV, Cunha RA, Ribeiro JA. Cross talk between A1 and A2A adenosine receptors in the hippocampus and cortex of young adult and old rats. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3196–3203. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Norton GR, Woodiwiss AJ, McGinn RJ, Lorbar M, Chung ES, Honeyman TW, Fenton RA, Dobson JG, Jr, Meyer TE. Adenosine A1 receptor-mediated anti-adrenergic effects are modulated by A2a receptor activation in rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H341–H349. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tikh EI, Fenton RA, Dobson JG., Jr Contractile effects of adenosine A1 and A2A receptors in the isolated murine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H348–H356. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00740.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]