Abstract

Synaptic transmission is mediated by a complex set of molecular events that must be coordinated in time and space. While many proteins that function at the synapse have been identified, the signaling pathways regulating these molecules are poorly understood. Pak5 (p21-activated kinase 5) is a brain-specific isoform of the group II Pak kinases whose substrates and roles within the central nervous system are largely unknown. To gain insight into the physiological roles of Pak5, we engineered a Pak5 mutant to selectively radiolabel its substrates in murine brain extract. Using this approach, we identified two novel Pak5 substrates, Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1, proteins that directly interact with one another to regulate synaptic vesicle endocytosis and recycling. Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 were phosphorylated by Pak5 and the other group II Paks in vitro, and Pak5 phosphorylation promoted Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding both in vitro and in vivo. These results implicate Pak5 in Pacsin1- and Synaptojanin1-mediated synaptic vesicle trafficking and may partially account for the cognitive and behavioral deficits observed in group II Pak-deficient mice.

Keywords: Syndapin1, F-BAR, autoinhibition, kinase substrate

Regulated signal transduction at neuronal synapses underlies the development and function of the nervous system and is crucial for proper neurotransmission. This is highlighted by a number of neurological disorders such as mental retardation and autism that result from defects in synaptic signaling cascades (1). In particular, aberrant signaling by protein kinases functioning downstream of Rho GTPases has been linked to these disorders (2, 3). Inactivation of both the RhoA/Rho-kinase (ROCK) pathway and the Rac/Cdc42/p21-activated kinase (Pak) pathway have been implicated in the development of mental retardation through dysregulation of neurotransmitter receptor endocytosis and trafficking (4–6). Loss of Pak3 expression as well as specific mutations in PAK3 are associated with abnormalities in synaptic plasticity and cognition (6, 7) and a decreased density of dendritic spines (8). In addition, both Pak1 and Pak3 are involved in regulating brain mass through modulation of neuronal size and synaptic complexity (9). These findings underscore the need to further characterize the roles of protein kinases, particularly those of the Pak family, in neuronal physiology and pathology.

Pak5 is a brain-specific serine/threonine protein kinase expressed exclusively in neurons but not glial cells (10) and whose functions within the central nervous system are poorly described (11). Six Pak isoforms exist in mammals, classified into two groups based on sequence homology and regulatory properties. The roles of the group I Paks (Pak1–3) in signaling pathways that mediate cell motility, proliferation, and survival are well documented; however, the functions of the group II Paks (Pak4–6) are much less well understood (12).

Among the group II Paks, only Pak4 is ubiquitously expressed and is essential for viability (13), whereas Pak5 and Pak6 have a more limited tissue expression pattern with especially high levels in the brain (14, 15). Consistent with some level of functional redundancy between these Pak isoforms, no phenotype has been reported for PAK5 or PAK6 single knockout mice (10, 16), but PAK5/PAK6 double knockout mice exhibit defects in behavior, memory, and learning (16). The molecular mechanisms underlying these cognitive defects, however, have yet to be determined.

To gain further insight into the functions of Pak5 in vivo, we identified and purified direct substrates of this kinase from murine brain extract. Here we report the identification of two novel Pak5 substrates, Synaptojanin1 and Pacsin1, proteins that directly bind to one another at the synapse to regulate vesicle dynamics. Furthermore, Pak5 phosphorylation promotes the interaction of Synaptojanin1 with Pacsin1, implicating Pak5 in synaptic vesicle trafficking.

Results

Identification of Pak5-Specific Substrates in Murine Brain.

Gatekeeper residue mutants of several protein kinases have been employed as tools to identify direct kinase substrates (17). These mutations enlarge the ATP binding pocket to accommodate the binding of unnatural ATP analogues modified by bulky substituents at the N6 position that the majority of wild-type kinases cannot use. A gatekeeper residue mutant, Pak5-M523G, but not wild-type Pak5, can utilize [32P]-N6-methylbenzyl-ATP to phosphorylate Pak1 (18) and myelin basic protein (MBP) (Fig. S1). Likewise, we found that the analogous Pak2 mutant (M323G) can also utilize [32P]-N6-methylbenzyl ATP as a substrate whereas wild-type Pak2 cannot (Fig. S1). We used these Pak2/5 mutants to identify direct and specific substrates of Pak5 in fractionated mouse brain lysates (Fig. S2).

Brain extract was fractionated by cation exchange chromatography and a sample of each fraction was incubated with either [32P]-N6-methylbenzyl-ATP alone or together with Pak5-M523G. Reactions were analyzed by Coomassie blue-stained SDS/PAGE and autoradiography to identify fractions containing proteins phosphorylated in a Pak5-dependent manner. A Pak5 substrate of 150 kDa and a second substrate of 55 kDa were identified, and fractions containing these proteins were pooled and further fractionated by anion exchange chromatography. Individual fractions containing p150 and p55 were identified by Pak5-M523G kinase assays. In parallel, each fraction was also subjected to kinase assays using Pak2-M323G. Both p150 and p55 were specifically phosphorylated by Pak5 but not Pak2 (Fig. 1). Coomassie blue-stained bands that correlated by molecular weight and by cofractionation with the [32P]-labeled substrates were excised and subjected to identification by MS/MS mass spectrometry of tryptic peptides. Seventy-three peptides corresponding to 55% of the amino acid sequence of Synaptojanin1 were identified in the 150 kDa band, representing more total peptide counts and greater percent coverage than any other protein identified in this band (Fig. S3A). Similarly, the protein with the most peptide counts (36 peptides) and greatest percent coverage (64%) in the 55 kDa band was Pacsin1 (Fig. S3B). Importantly, Synaptojanin1 and Pacsin1 have calculated molecular weights of 145 kDa and 52 kDa, respectively, consistent with the observed mobility of the Pak5 substrates by SDS/PAGE.

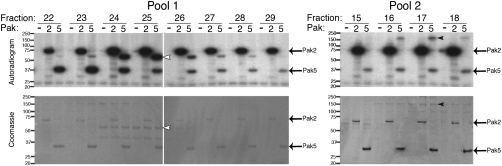

Fig. 1.

Identification of two Pak5 specific substrates in murine brain. Autoradiograms and corresponding Coomassie-blue-stained gels of pools 1 and 2. White arrowhead highlights the 55-kDa Pak5-specific substrate in pool 1. Black arrowhead highlights the 150-kDa Pak5-specific substrate in pool 2.

Synaptojanin1 and Pacsin1 Are Novel Pak5 Substrates.

Synaptojanin1 is a member of the phosphoinositide 5-phosphate family of phosphatases. This enzyme dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a prerequisite for the uncoating and recycling of synaptic vesicles (19). As a consequence, Synaptojanin1-/- mice display elevated steady-state levels of PIP2 with an accumulation of clathrin-coated vesicles in nerve terminals, and these animals die shortly after birth (20). To confirm the identity of the 150-kDa band as Synaptojanin1, we immunodepleted a p150-containing fraction with a Synaptojanin1 antibody. Western blotting with the same antibody demonstrated depletion of this band from the fraction and its appearance in the immunoprecipitate (Fig. 2A, Upper). Samples of the starting fraction, the immunodepleted fraction, and the immunoprecipitated material were then used in an in vitro kinase assay with recombinant Pak5 (Fig. 2A, Lower). A 150-kDa band was radiolabeled only when Pak5 was present, did not appear in the kinase assay using the immunodepleted fraction, and was present in the anti-Synaptojanin1 immunoprecipitate. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the 150-kDa Pak5 substrate is Synaptojanin1.

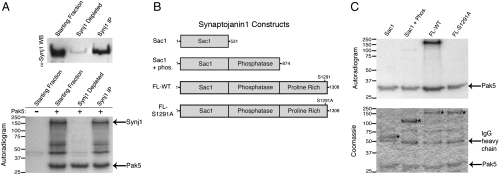

Fig. 2.

The p150 Pak5 substrate is the phosphoinositide phosphatase Synaptojanin1. (A) Immunodepletion and kinase assays using a p150-containing fraction. Fraction 17 (Fig. 1, pool 2) was immunodepleted with an anti-Synaptojanin1 antibody and the starting fraction, depleted fraction, and immunoprecipitated material were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Synaptojanin1 antibody (Top) and by Pak5 in vitro kinase assays (Bottom). (B) Synaptojanin1 domain architecture and truncation/point mutants tested for Pak5 phosphorylation. All constructs were myc-tagged at the C terminus. (C) Mapping of the Pak5 phosphorylation site in Synaptojanin1. The indicated constructs were expressed in and immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells and used in Pak5 in vitro kinase assays. Reactions were analyzed by Coomassie-blue-stained SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Asterisks denote bands corresponding to Synaptojanin1 proteins.

Synaptojanin1 consists of an N-terminal Sac1 phosphatase domain, a central 5- phosphatase domain, and a C-terminal proline-rich domain (Fig. 2B). To determine which domain(s) of Synaptojanin1 are phosphorylated by Pak5, full-length Synaptojanin1 or truncation constructs (Fig. 2B) were expressed, immunopurified, and used in in vitro kinase assays with Pak5 (Fig. 2C). Synaptonjanin1 is phosphorylated only in constructs containing the proline-rich domain, indicating that the phosphorylation site(s) likely resides within this region.

To predict the specific phosphorylation site within this domain, we elucidated the amino acid sequence selectivity of Pak5 using a positional scanning peptide library approach (Fig. S4). This method uses partially degenerate peptide mixtures to systematically test all of the naturally occurring amino acids at each of nine positions surrounding a phosphoacceptor site for phosphorylation by a given kinase (21). Overall, we found that the peptide substrate specificity for Pak5 was indistinguishable from the previously reported specificity of Pak4 (22), and like all other Pak isoforms, the most important determinant for Pak5 phosphorylation is the presence of an arginine at the -2 position. However, unlike the group I isoforms Pak1 and Pak2 (22), the second strongest positive selection by Pak5 was for serine at the +3 position. The Pak5 selectivity data was used to quantitatively rank all possible sites for Pak5 phosphorylation within the proline-rich domain of Synaptojanin1, and serine 1291 ranked as the most likely site by this analysis. When we mutated serine 1291 to alanine (S1291A) within the context of the full-length protein, it was no longer phosphorylated, indicating that Pak5 phosphorylates Synaptojanin1 exclusively on serine 1291.

Pacsin1, also known as Syndapin1, is an evolutionarily conserved, brain-specific F-BAR (Fer-Cip4-Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs) and SH3 (Src homology 3)-domain-containing protein (23, 24). The SH3 domain of Pacsin1 binds to the proline-rich regions of several other proteins including dynamin1, N-WASP (neuronal Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein), and Synaptojanin1 (25) while the F-BAR domain is implicated in sensing and/or inducing membrane curvature (26). Pacsin1 was immunoprecipitated from a p55-containing fraction, and the starting fraction, the immunodepleted fraction, and the beads from the immunoprecipitation were analyzed by Western blotting to confirm Pacsin1 depletion (Fig. 3A, Top). Samples of the starting fraction, the immunodepleted fraction, and the immunoprecipitate were then used in Pak5 kinase assays (Fig. 3A, Lower). A 55-kDa band was strongly radiolabeled by Pak5 in Pacsin1 immunoprecipitates, demonstrating that Pacsin1 is the 55-kDa substrate of Pak5.

Fig. 3.

The p55 Pak5 substrate is the F-BAR family member Pacsin1/Syndapin1. (A) Immunodepletion and kinase assays using a p55-containing fraction. Fraction 25 (Fig. 1, pool 1) was immunodepleted with an anti-Pacsin1 antibody and the starting fraction, depleted fraction, and immunoprecipitated material were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Pacsin1 antibody (Top) and by Pak5 in vitro kinase assays (Bottom). (B) Pacsin1 domain architecture and truncation/point mutants analyzed for Pak5 phosphorylation. The indicated constructs were expressed and purified as GST-fusion proteins from E. coli. (C) Mapping of the Pak5 phosphorylation site in Pacsin1. Pak5 kinase assays were performed with the indicated GST-Pacsin1 fusion proteins as substrates. Reactions were analyzed by Coomassie-blue-stained SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. Asterisks denote bands corresponding to Pacsin1. Note that the GST-SH3 domain fusion comigrates with Pak5.

Pacsin1 contains an N-terminal F-BAR domain and a C-terminal SH3 domain connected by an unstructured linker region (Fig. 3B). To determine which domains of Pacsin1 are phosphorylated by Pak5, we expressed and purified GST-fusion proteins consisting of various regions of Pacsin1 (Fig. 3B). Only Pacsin1 constructs containing the linker region were phosphorylated by Pak5 (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that Pak5 likely phosphorylates a site within this region. Pak5 consensus sequence analysis ranked serine 343 as the most likely candidate, and consequently, its mutation to alanine (S343A) within the context of the full-length protein abolished phosphorylation by Pak5 (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that Pak5 phosphorylates Pacsin1 exclusively on serine 343.

Three isoforms of Pacsin are expressed in higher eukaryotes. Pacsin1 is brain-specific whereas Pacsin2 and Pacsin3 are more widely expressed (27). An alignment of the sequences of Pacsin1/2/3 reveals that serine 343 within the Pak family consensus motif is not conserved in Pacsin2 and 3 (Fig. S5A). Consistent with this finding, Pacsin1 is phosphorylated in vitro by Pak5 whereas Pacsin2 and 3 are not (Fig. S5B), demonstrating that only the brain-specific Pacsin1 isoform is a substrate of Pak5.

Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 are Group II Pak-Specific Substrates.

Although the kinase domains of the group I and group II Paks are quite divergent, the majority of group II Pak substrates are also phosphorylated by the group I Paks (12). Our data indicate that Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 are phosphorylated specifically by Pak5 but not by Pak2 (Fig. 1), suggesting that these proteins may be group II-specific Pak substrates. To directly test this, we performed in vitro kinase assays with all six Pak isoforms using GST-Pacsin1 or Synaptojanin1-myc and, as a control, the generic Pak substrate MBP. Whereas MBP is phosphorylated by all Pak isoforms (Fig. 4 A and B, Lower Panels), Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 are preferentially phosphorylated by all three of the group II Paks (Fig. 4 A and B, Upper Panels, lanes 5–7, and Fig. 4C) but not by the group I Paks (Fig. 4 A and B, Upper Panels, lanes 1, 2, and 4, and Fig. 4C).

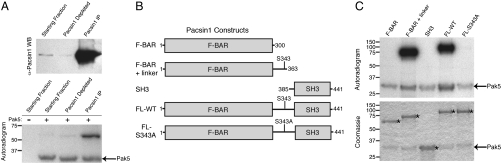

Fig. 4.

Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 are preferentially phosphorylated in vitro by group II Paks. (A and B) Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 are group II Pak-specific substrates. GST-Pacsin1 (Fig. 4A, Upper Panels), Synaptojanin1-myc (Fig. 4B, Upper Panels) and MBP (Lower Panels) were used as substrates in in vitro kinase assays with Paks1-6 and Pak2-P286Q/K287R (Pak2-QR). Reactions were analyzed by silver-stained or Coomassie-blue-stained SDS/PAGE, as indicated, and autoradiography. * indicates autophosphorylation of the corresponding Pak isoform. (C) Bands were quantified and plotted as the ratio of Pacsin1 or Synaptojanin1 phosphorylation to MBP phosphorylation. Gray bars denote Paks with group I specificity and black bars denote Paks with group II specificity.

Two amino acids have been shown to play a critical role in dictating the substrate selectivity of all Paks by influencing the preferences of these kinases for particular residues at the +2 and +3 positions of a substrate (22). Exchange of these residues partially swaps the peptide substrate specificity of group I to that of group II and vice versa (22). Therefore, we asked whether the specificity-swapping mutant of Pak2 (P286Q, K287R; Pak2-QR) could phosphorylate Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 in vitro. The results indicate that Pak2-QR was able to phosphorylate both substrates whereas wild-type Pak2 could not (Fig. 4 A and B, Upper Panels, lanes 2 and 3, and Fig. 4C), suggesting that recognition of the motif surrounding the phosphoacceptor residue in these proteins confers group II Pak selectivity. To directly test this, we generated an 11 amino acid GST-fusion peptide consisting of the residues immediately flanking the Pak5 phosphorylation site in Pacsin1 (GST-AGDRGSVSSYD) and used this fusion peptide as a substrate in in vitro kinase assays with Pak2 or Pak5. Whereas both Pak2 and Pak5 robustly phosphorylated MBP (Fig. S6, lanes 3 and 4), this short peptide was strongly phosphorylated by Pak5 but to a much lesser degree by Pak2 (Fig. S6, lanes 7 and 8), demonstrating that these residues form a specific recognition site for group II Paks.

Pacsin1 Is Phosphorylated in Vivo by Group II Paks.

To determine the physiological relevance of Pak5 phosphorylation, we developed a phosphospecific antibody against Pacsin1-S343 (Fig. S7A). A single band of 52 kDa was detected by Western blotting using the antibody, indicating that Pacsin1 is phosphorylated in vivo on serine 343 (Fig. S7B). Corroborating this result, phosphorylation of serine 343 in Pacsin1 has been detected by a large-scale mass spectrometry-based analysis of the mouse phosphoproteome (28).

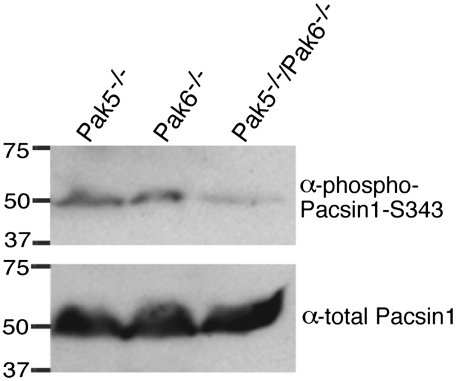

To test if phosphorylation of serine 343 was dependent on group II Paks, brain lysates were prepared from Pak5 and Pak6 single and double knockout mice and were immunoblotted with a total Pacsin1 antibody and with the phospho-Pacsin1-S343 antibody. Brain lysates from Pak5/Pak6 double knockout mice revealed substantially decreased levels of phosphorylated Pacsin1 compared to the single knockouts (Fig. 5) with the residual phosphorylation likely due to the presence of Pak4, which is also expressed in the brain (13). Taken together, these data indicate that Pacsin1 is phosphorylated by Pak5 and Pak6 in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Pacsin1-S343 is phosphorylated in vivo in a Pak5/Pak6-dependent manner. Brain lysates from mice of the indicated genotypes were immunoblotted with a phospho-Pacsin1-S343 antibody and with a total Pacsin1 antibody.

Phosphorylation by Group II Paks Regulates Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 Binding.

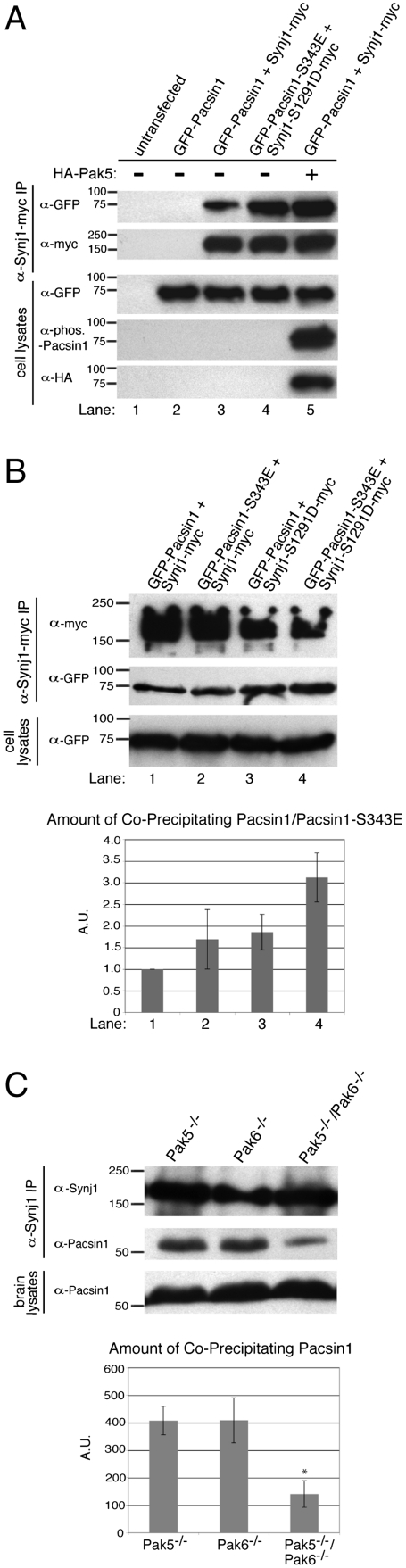

The SH3 domain of Pacsin1 binds to the proline-rich domain of Synaptojanin1 (25). The identification of both Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 as Pak5 substrates and the subsequent mapping of phosphorylation sites to, or adjacent to, regions in these proteins involved in their association (Figs. 2C and 3C) led us to hypothesize that Pak5 phosphorylation may affect their binding. To test this, we transfected HEK293 cells with constructs encoding Synaptojanin1-myc and GFP-Pacsin1 with or without a plasmid encoding HA-Pak5. Synaptojanin1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and the extent of Pacsin1 coprecipitation was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies (Fig. 6A). The results indicate that a greater amount of Pacsin1 coprecipitated with Synaptojanin1 when Pak5 is expressed (compare lanes 3 and 5 in Fig. 6A), implying that phosphorylation by Pak5 increases their association. We tested this via an alternative approach by cotransfection of epitope-tagged phosphomimetic forms of both Synaptojanin1 (S1291D) and Pacsin1 (S343E). Consistent with the previous result, the phosphomimetic forms (Fig. 6A, lane 4) showed increased binding compared to the wild-type proteins (Fig. 6A, lane 3). Taken together, these two independent approaches demonstrate that Pak5 phosphorylation promotes the interaction of Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1.

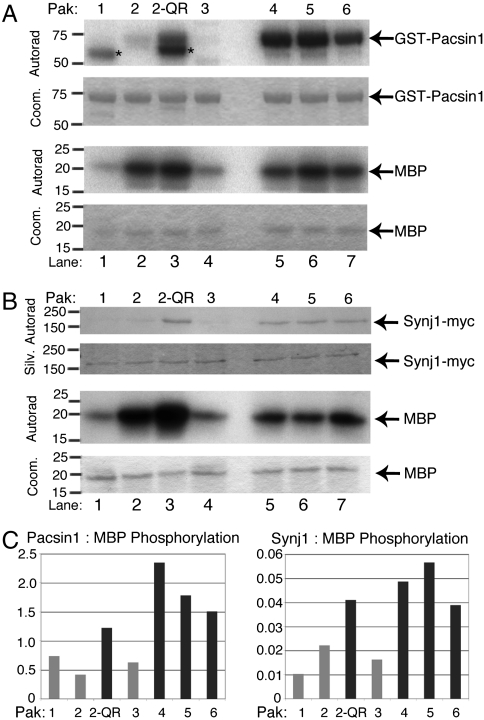

Fig. 6.

Phosphorylation by group II Paks regulates Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding. (A and B) Phosphorylation of Pacsin1-S343 and Synaptojanin1-S1291 enhances Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding in vitro. HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. The amount of GFP-Pacsin1 or GFP-Pacsin1-S343E coprecipitating with Synaptojanin1 or Synaptojanin1-S1291D was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies. Immunoblotting of whole cell lysates demonstrates equal expression of GFP-Pacsin1/GFP-Pacsin1-S343E and detection of HA-Pak5 and phospho-Pacsin1-S343 in the relevant samples. Bands from B (Middle) were quantified and normalized to the amount of wild-type Pacsin1 coprecipitating with wild-type Synaptojanin1 (lane 1). Means from three independent experiments are displayed. Error bars denote standard deviation. (C) Phosphorylation by group II Paks regulates Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding in vivo. Endogenous Synaptojanin1 was immunoprecipitated from brain lysates of mice of the indicated genotypes (Top). The amount of coprecipitating endogenous Pacsin1 (Middle) was determined by immunoblotting along with levels of total Pacsin1 (Bottom). Bands were quantified and are displayed as the mean from three independent experiments. Error bars denote standard deviation, and * indicates p value < 0.01 for the double knockout compared to either single knockout. A.U. = arbitrary units.

We further probed the individual contribution of each phosphosite on Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding by coimmunoprecipitation from cells expressing both wild-type proteins, both phosphomimetic mutants, or one phosphomimetic mutant with the other wild-type protein. While expression of either phosphomimetic enhances Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 3), greatest binding is detected by coexpression of both phosphomimetic forms (Fig. 6B, lane 4). These results suggest that both sites of phosphorylation (S343 in Pacsin1 and S1291 in Synaptojanin1) contribute to the Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 interaction.

Finally, we investigated the physiological relevance of group II Pak phosphorylation on Pacsin1-Synaptojanin1 binding in the brain. Endogenous Synaptojanin1 was immunoprecipitated from brain lysates of Pak5 and Pak6 single knockout and Pak5/Pak6 double knockout mice. Substantially less Pacsin1 coprecipitated with Synaptojanin1 from brains of Pak5/Pak6 double knockout mice compared to the single knockouts (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these results indicate that phosphorylation by group II Paks regulates the interaction between Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 both in vitro and in vivo.

Discussion

Among the six p21-activated kinases, Pak5 is one of the least characterized and most poorly understood isoforms. Previous reports have described a role for Pak5 in antiapoptotic signaling (29) (30), and overexpression of Pak5 results in increased neurite outgrowth in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells (31), although the mechanism by which Pak5 mediates this effect is unknown. Several other Pak5 substrates have been identified including p120-catenin (32), Raf-1 (33), and Par-1 (34), but given the widespread expression of these proteins and the brain-restricted expression of Pak5, the physiological implications of these modifications is unclear.

In this study, we demonstrate that Pak5 directly phosphorylates Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 in brain cytosol enhancing their association and possibly linking the activities of these two proteins both spatially and temporally. In neuromorphogenesis, Pacsin1 functions at the interface of endocytosis and membrane trafficking, acting as an adaptor to link membrane deformation via its F-BAR domain to vesicle internalization and trafficking via its SH3 domain (24, 35). Also functioning in neurons, the phosphatase activity of Synaptojanin1 is crucial for phosphoinositide homeostasis and for the maintenance of a functional pool of synaptic vesicles (36). Our data illustrating a role for Pak5 in mediating the interaction between Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 connect aspects of endocytosis and membrane recycling at the synapse and provide insight into how the functions of Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 may be coordinated in vivo.

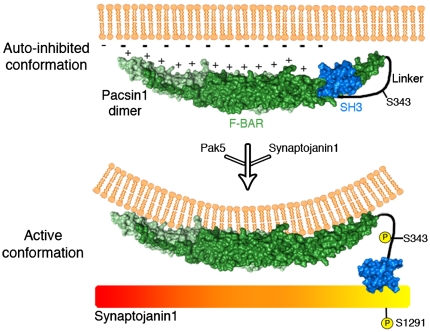

Recent structural studies have determined that Pacsin1 exists in an autoinhibited conformation in which the SH3 domain is bound to the F-BAR domain within the same molecule. This autoinhibited conformation is incompatible with SH3 domain-ligand binding and inhibits membrane tubulation by the F-BAR domain (37). We propose a model in which phosphorylation of Pacsin1 at serine 343 by Pak5 relieves this autoinhibition, allowing the F-BAR domain to generate membrane curvature and the SH3 domain to bind Synaptojanin1 (Fig. 7). We further speculate that serine 1291 phosphorylation induces a conformational change in Synaptojanin1 that enhances binding to the SH3 domain of Pacsin1.

Fig. 7.

Model: group II Paks regulate the F-BAR- and SH3 domain-mediated functions of Pacsin1. Phosphorylation by group II Paks (e.g., Pak5) and/or binding of phosphorylated Synaptojanin1 relieves intrinsic Pacsin1 autoinhibition by inducing a conformational change in the linker region. This allows the F-BAR domain of Pacsin1 to interact with and deform the plasma membrane and may enhance binding of ligands (i.e., additional molecules of Synaptojanin1) to the SH3 domain. A surface representation of the dimeric F-BAR domain (green) and the SH3 domain (blue) of Pacsin1 were generated using Pymol (Schrodinger, LLC) based on the crystal structure (37) (PDB ID code 2X3X). The linker region was disordered in the crystal and is represented here by a black line.

In support of this model, phosphoregulation of F-BAR- and SH3-domain-containing proteins is emerging as a common mechanism to modulate the conformation, subcellular localization, and activity of proteins that contain these domains (38). A striking difference between these proteins and Pacsin1, however, is that phosphorylation inhibits their association with known ligands while phosphorylation of Pacsin1 appears to promote its interaction with a known binding partner. A possible explanation for this discrepancy may be the fact that the linker regions connecting the F-BAR and SH3 domains in all of these proteins are phosphorylated at multiple sites. We propose that these linker regions function as platforms for signal integration from a number of kinases and phosphatases that ultimately determines whether the overall effect on protein function is stimulatory or inhibitory.

Within the central nervous system, the strength and maturity of synaptic connections is defined by the number and types of neurotransmitter receptors at the postsynaptic membrane. Pacsin1 binds to NR3A-containing NMDA receptors and promotes their endocytosis (39), and Synaptojanin1 has also been implicated in endocytosis (40), specifically in postsynaptic AMPA receptor downregulation (41). Pak5-/-/Pak6-/- mice exhibit defects in locomotion, learning, and memory (16), and based on our results, we propose that the cognitive and behavioral deficits observed in these mice may be partly attributable to altered endocytosis and vesicle trafficking. Learning and memory, in particular, are dependent on a form of synaptic plasticity known as long-term potentiation, a process that relies heavily on the density of neurotransmitter receptors within the postsynaptic membrane (42). Defects in Synaptojanin1-Pacsin1-linked synaptic vesicle dynamics may perturb the number of NMDA- and AMPA-type receptors at the plasma membrane with a subsequent inhibition of long-term potentiation.

Our data indicate that Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 are phosphorylated by the group II Paks but not by the group I Paks, representing, to our knowledge, Pak substrates that are phosphorylated solely by the group II isoforms. Furthermore, our results suggest that the amino acid context surrounding the Pacsin1 phosphorylation site dictates a strong preference for recognition by the group II Paks, implying that the peptide substrate specificity differences identified in vitro for group I vs. group II Paks (22) are physiologically relevant.

The Pak5 phosphorylation sites and key elements of the Pak consensus motif in both Synaptojanin1 and Pacsin1 are evolutionarily conserved from jawed fish to mammals (Fig. S8), suggesting important biological functions for these modifications. Interestingly, the presence of these proteomic features coincides with the acquisition of myelinated nerve fibers (43). It is therefore tempting to speculate that myelination and Pak5-mediated phosphorylation of Pacsin1 and Synaptojanin1 coevolved, as Pak5-induced association of Synaptojanin1 and Pacsin1 may enhance synaptic vesicle recycling and, like myelination, may facilitate neurotransmission.

Materials and Methods

Pak5 Substrate Identification.

Wild-type murine brain extract was fractionated by cation and anion exchange chromatography, and samples of each fraction were subjected to in vitro kinase assays. Additional details are available as supplemental information.

Experimental details regarding antibodies, plasmid construction, recombinant protein expression and purification, generation of [32P]-N6-methylbenzyl ATP, preparation of mouse brain extract, chromatography, characterization of Pak5 substrate specificity determinants, in vitro kinase assays, cell culture and transfection, and coimmunoprecipitation assays are available as supplemental information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank P. De Camilli, S. Knapp, J. Chernoff, M. Kelly, J. Fukui, L. O’Donnell, G. Rall, and W. Xu for reagents and discussions. This work was supported by a W. W. Smith Charitable Trust Award to J.R.P., by an American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship (PF-11-068-01-TBE) to T.I.S., and by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM083025 to J.R.P., T32 CA009035 to T.I.S., and P30 CA006927 to Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1116560109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Boda B, Dubos A, Muller D. Signaling mechanisms regulating synapse formation and function in mental retardation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadif Kasri N, Van Aelst L. Rho-linked genes and neurological disorders. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455:787–797. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0385-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreis P, Barnier JV. PAK signalling in neuronal physiology. Cell Signal. 2009;21:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadif Kasri N, Nakano-Kobayashi A, Malinow R, Li B, Van Aelst L. The Rho-linked mental retardation protein oligophrenin-1 controls synapse maturation and plasticity by stabilizing AMPA receptors. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1289–1302. doi: 10.1101/gad.1783809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rex CS, et al. Different Rho GTPase-dependent signaling pathways initiate sequential steps in the consolidation of long-term potentiation. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:85–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boda B, et al. The mental retardation protein PAK3 contributes to synapse formation and plasticity in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10816–10825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2931-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng J, Meng Y, Hanna A, Janus C, Jia Z. Abnormal long-lasting synaptic plasticity and cognition in mice lacking the mental retardation gene Pak3. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6641–6650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0028-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreis P, et al. The p21-activated kinase 3 implicated in mental retardation regulates spine morphogenesis through a Cdc42-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21497–21506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang W, et al. p21-Activated kinases 1 and 3 control brain size through coordinating neuronal complexity and synaptic properties. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:388–403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00969-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Minden A. Targeted disruption of the gene for the PAK5 kinase in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7134–7142. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7134-7142.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells CM, Jones GE. The emerging importance of group II PAKs. Biochem J. 2010;425:465–473. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arias-Romero LE, Chernoff J. A tale of two Paks. Biol Cell. 2008;100:97–108. doi: 10.1042/BC20070109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qu J, et al. PAK4 kinase is essential for embryonic viability and for proper neuronal development. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7122–7133. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7122-7133.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandey A, et al. Cloning and characterization of PAK5, a novel member of mammalian p21-activated kinase-II subfamily that is predominantly expressed in brain. Oncogene. 2002;21:3939–3948. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SR, et al. AR and ER interaction with a p21-activated kinase (PAK6) Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:85–99. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekrasova T, Jobes ML, Ting JH, Wagner GC, Minden A. Targeted disruption of the Pak5 and Pak6 genes in mice leads to deficits in learning and locomotion. Dev Biol. 2008;322:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elphick LM, Lee SE, Gouverneur V, Mann DJ. Using chemical genetics and ATP analogues to dissect protein kinase function. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:299–314. doi: 10.1021/cb700027u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deacon SW, et al. An isoform-selective, small-molecule inhibitor targets the autoregulatory mechanism of p21-activated kinase. Chem Biol. 2008;15:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPherson PS, et al. A presynaptic inositol-5-phosphatase. Nature. 1996;379:353–357. doi: 10.1038/379353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cremona O, et al. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 1999;99:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutti JE, et al. A rapid method for determining protein kinase phosphorylation specificity. Nat Methods. 2004;1:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rennefahrt UE, et al. Specificity profiling of Pak kinases allows identification of novel phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15667–15678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plomann M, et al. PACSIN, a brain protein that is upregulated upon differentiation into neuronal cells. Eur J Biochem. 1998;256:201–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2560201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessels MM, Qualmann B. The syndapin protein family: Linking membrane trafficking with the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3077–3086. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qualmann B, Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Kelly RB. Syndapin I a synaptic dynamin-binding protein that associates with the neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:501–513. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q, et al. Molecular mechanism of membrane constriction and tubulation mediated by the F-BAR protein Pacsin/Syndapin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12700–12705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902974106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modregger J, Ritter B, Witter B, Paulsson M, Plomann M. All three PACSIN isoforms bind to endocytic proteins and inhibit endocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:4511–4521. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huttlin EL, et al. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell. 2010;143:1174–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cotteret S, Chernoff J. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Pak5 regulates its antiapoptotic properties. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3215–3230. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3215-3230.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotteret S, Jaffer ZM, Beeser A, Chernoff J. p21-Activated kinase 5 (Pak5) localizes to mitochondria and inhibits apoptosis by phosphorylating BAD. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5526–5539. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5526-5539.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dan C, Nath N, Liberto M, Minden A. PAK5, a new brain-specific kinase, promotes neurite outgrowth in N1E-115 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:567–577. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.567-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong LE, Reynolds AB, Dissanayaka NT, Minden A. p120-catenin is a binding partner and substrate for group B Pak kinases. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:1244–1254. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Carr HS, Dan I, Ruvolo PP, Frost JA. p21 activated kinase 5 activates Raf-1 and targets it to mitochondria. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:167–175. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matenia D, et al. PAK5 kinase is an inhibitor of MARK/Par-1, which leads to stable microtubules and dynamic actin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4410–4422. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dharmalingam E, et al. F-BAR proteins of the syndapin family shape the plasma membrane and are crucial for neuromorphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13315–13327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3973-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim WT, et al. Delayed reentry of recycling vesicles into the fusion-competent synaptic vesicle pool in synaptojanin 1 knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:17143–17148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222657399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao Y, et al. Molecular basis for SH3 domain regulation of F-BAR-mediated membrane deformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8213–8218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003478107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts-Galbraith RH, Gould KL. Setting the F-BAR: functions and regulation of the F-BAR protein family. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4091–4097. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.20.13587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Otano I, et al. Endocytosis and synaptic removal of NR3A-containing NMDA receptors by PACSIN1/syndapin1. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:611–621. doi: 10.1038/nn1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mani M, et al. The dual phosphatase activity of synaptojanin1 is required for both efficient synaptic vesicle endocytosis and reavailability at nerve terminals. Neuron. 2007;56:1004–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong LW, De Camilli P. Regulation of postsynaptic AMPA responses by synaptojanin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17561–17566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809221105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee HK, Kirkwood A. AMPA receptor regulation during synaptic plasticity in hippocampus and neocortex. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;5:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zalc B, Goujet D, Colman D. The origin of the myelination program in vertebrates. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R511–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.