Abstract

The scope of isonitrile-mediated amide bond-forming reactions is further explored in this second-generation synthetic approach to cyclosporine (cyclosporin A). Both type I and type II amidations are utilized in this effort, allowing access to epimeric cyclosporins A and H from a single precursor by variation of the coupling reagents. This work lends deeper insight into the relative acylating ability of the formimidate carboxylate mixed anhydride (FCMA) intermediate, while shedding light on the far-reaching impact of remote stereochemical changes on the effective pre-organization of seco-cyclosporins.

Introduction

Long-standing interest in the chemical synthesis of proteins1 has served to spur the development of numerous methods for construction of the amide bond.2 These efforts have led to the advent of highly reactive coupling agents3 for step-by-step elongation as well as powerful strategies for segment condensation such as native chemical ligation.4 Notwithstanding the impressive progress that has unquestionably been achieved, only a subset of these methodologies are suitable for the formation of hindered peptide linkages involving amino acids that are either N-alkylated or doubly alkylated at the α-carbon.5 Modifications of bioactive polypeptide structures such as N-methylation can confer improved pharmacoproperties,6 but from a synthetic perspective their incorporation may not be simple. Hence, there remains a continuing impetus for investigating novel modes of amide formation.

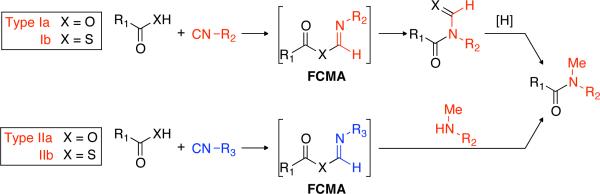

Considerations such as these prompted us to revisit the chemistry of isonitriles.7 Among other discoveries, two conceptually different but complementary approaches were developed to allow for ready access to N-methyl peptides (Scheme 1). In the first, a carboxylic acid and isonitrile are combined under microwave irradiation to provide an N-formyl amide (Type Ia).7a The analogous transformation of thioacids into N-thioformyl amides is even more facile, proceeding at ambient temperature (Type Ib).7h Under suitable reduction protocols, these Type I derived coupling products can be easily converted to their N-methylated counterparts. In the second method, the amide bond is fashioned when an exogenous secondary amine intercepts the presumed formimidate carboxylate mixed anhydride (FCMA) intermediate (Type II).7k In this format, an isonitrile serves to activate the acid, but the N-bound functionality of the isonitrile is not incorporated into the product. Use of a sterically encumbered “throwaway” isonitrile8 can be quite helpful in favoring the required bimolecular acylation pathway over internal O (or S) → N rearrangement, which would lead to an N-formyl amide carrying the nitrogen-bound functionality.7j

Scheme 1.

Isonitrile-based approaches to the construction of N-methyl amides.

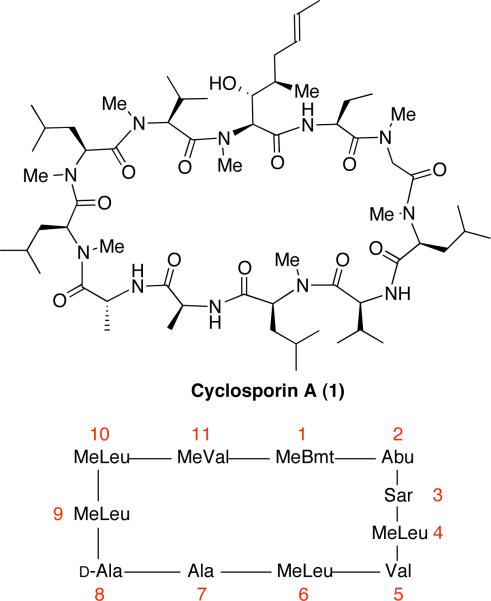

With these two general strategies in mind, we turned to the synthesis of the historically important natural product cyclosporine (1), a cyclic undecapeptide with seven N-methyl amide functions (Figure 1). Discovered in the early 1970s in the context of an extract from the fungus Tolypocladium inflatum Gams,9 cyclosporin A was noted by scientists at the Sandoz company to have a unique biological profile in that it possesses significant immunosuppressive activity with manageable cytotoxicity.10 Its structure was deduced on the basis of chemical degradation, NMR, and X-ray crystallographic analysis.11 Subsequently, Wenger accomplished a total synthesis of cyclosporine, which he disclosed in a series of landmark papers published in 1983–1984.12 The remarkable ability of certain cyclosporins to prevent rejection of grafted organs transformed the field of organ transplantation.13 Moreover, elucidation of its mechanism of action14 served to illuminate a key signal transduction pathway in T cell biology.15

Figure 1.

Structure of cyclosporin A.

In light of these structurally realized translational features, we undertook a new total synthesis of cyclosporin A and did indeed succeed in a “first generation” synthesis in which isonitriles served to mediate the construction of five of the seven N-methyl amides as well as the final macrolactamization.71 Herein, we sought to establish all of the amides (secondary and tertiary) of cyclosporin A via isonitrile-mediated chemistry, thereby confronting some significant new issues in isonitrile-mediated amidation. In the course of this work, we serendipitously unveiled some intriguing modes of selectivity during the macrolactamization of diastereomeric cyclosporin seco-acids.

Results and Discussion

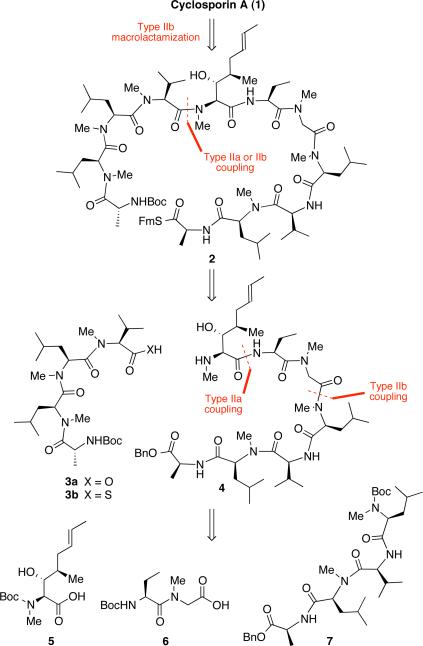

Our retrosynthetic strategy, in broad outline, followed the lead of Wenger,12c who disconnected the macrocycle at the Ala(7)-D-Ala(8) junction, the only site between consecutive non-N-methylated amides (Scheme 2). We further anticipated that the requisite linear undecapeptide 2 might be fashioned by the joining of tetrapeptide 3 and heptapeptide 4, appreciating that such a coupling might well be challenging due to steric hindrance near the reacting functional groups and owing to the potential for epimerization. In a similar vein, we hoped to evaluate the proficiency of both carboxylic acid 3a and thioacid 3b in the reaction. Further disconnection of 4 revealed the MeBmt ((4R)-4-((E)-2-butenyl)-4, N-dimethyl-l-threonine)-derived residue 5, dipeptide acid 671 and tetrapeptide 7 as milestone building blocks. The unnatural amino acid derivative 5 was to be prepared via the route described by Evans and co-workers.16 The remaining individual peptide fragments would be assembled via sequential Type II couplings.

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis of cyclosporin A.

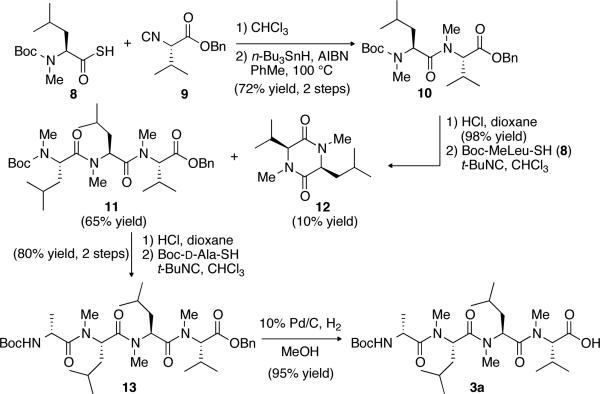

We began our synthetic efforts by targeting tetrapeptide carboxylic acid 3a. Coupling of leucine-derived thioacid 871 with valine isonitrile 97f followed by radical reduction (with n-Bu3SnH and azobis-(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN)) at 100 °C in toluene afforded the corresponding N-methyl dipeptide 7 in 72% yield over two steps (Scheme 3). Our early efforts at accomplishing this transformation had stalled at efficiencies of 40%, presumably due to the formation of side products, including thioacid anhydride and thioformamide.7h Ultimately, a simple experimental modification (slow addition of the thioacid via syringe pump) was made to maintain a low concentration of thioacid during the course of the reaction, thus minimizing side product formation due to undesired reaction of the thioacid with the FCMA intermediate.7j Attempts to extend the resulting dipeptide 10 with leucine thioacid 8 via t-butyl isonitrile activation were complicated by formation of significant amounts (ca. 30%) of diketopiperazine 12.12b This undesired cyclization product had been encountered earlier in the synthesis of multiply N-methylated peptides due to the slower coupling rates and increased propensity for occupying the cis amide conformation.5 Indeed, because of this issue, Wenger was unable to synthesize tripeptide 11 bearing a C-terminal benzyl ester by direct N-terminal extension (using the mixed pivalic anhydride method).12b Fortunately, formation of this side product could be limited by slow addition of the dipeptide amine hydrochloride salt in chloroform to a pre-mixed solution of thioacid and isonitrile, resulting in a 65% yield of 11, with only a 10% yield of 12. Further extension of 11 by a similar carbamate cleavage/isonitrile-mediated coupling sequence furnished tetrapeptide 13 in 80% yield. Hydrogenolysis of the benzyl ester afforded the corresponding tetrapeptide carboxylic acid 3a in 95% yield.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of tetrapeptide carboxylic acid 3a.

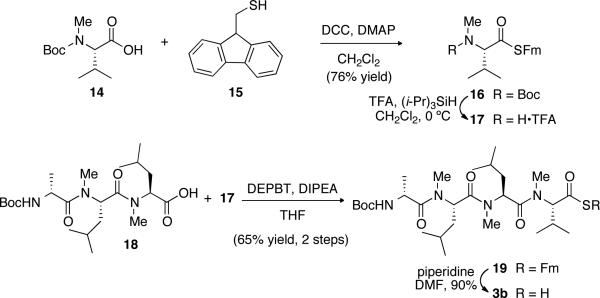

In order to evaluate the relative merits of our Type IIa and Type IIb coupling methods in the key segment coupling (3a + 4 and 3b + 4, respectively), we required access to tetrapeptide 3b (Scheme 4). The thioacid was initially introduced in protected form by reaction of valine-derived carboxylic acid 14 with (9H-fluoren-9-yl) methanethiol (FmSH 15)17 in the presence of N,N′—dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and DMAP to form 16 in 76% yield.18 Cleavage of the carbamate linkage under acidic conditions furnished valine-derived thioester 17. However, further extension of 17 by sequential C→N isonitrile couplings proved troublesome. The main issue was again diketopiperazine formation, though more significant this time due to the enhanced leaving group ability of the FmS. Ultimately, it was found to be more practical to arrive at 19 by an alternate route in which tripeptide acid 1812b was coupled to amino thioester 17, even though some degree of epimerization was observed. Use of 3-(diethylphosphoryloxy)-1,2,3-benzotriazin-4(3H)-one (DEPBT) in the coupling contained the epimerization to a manageable ~3:1 ratio, allowing the desired product 1919 to be obtained in 65% yield from 16. Final removal of the Fm group with piperidine in DMF afforded the desired tetrapeptide thioacid 3b in 90% yield.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of tetrapeptide thioacid 3b.

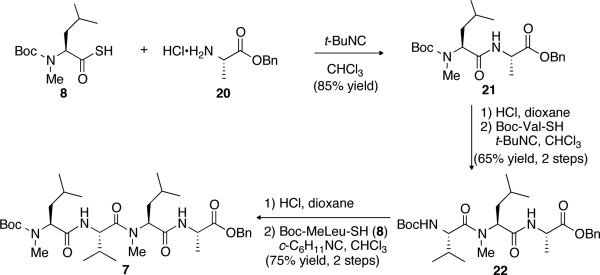

With tetrapeptide fragments 3a and 3b in hand, we turned our attention to the synthesis of tetrapeptide 7, which was readily accomplished using our Type II chemistry in sequential fashion (Scheme 5). First, thioacid 8 was treated with t-butyl isonitrile and amine salt 20 to produce dipeptide 21 in 85% yield. Subsequent removal of the carbamate and coupling with valine thioacid furnished tripeptide 22 in 65% yield over two steps. Tetrapeptide 7 was obtained in 75% yield by a similar N-terminal extension sequence.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of tetrapeptide 7.

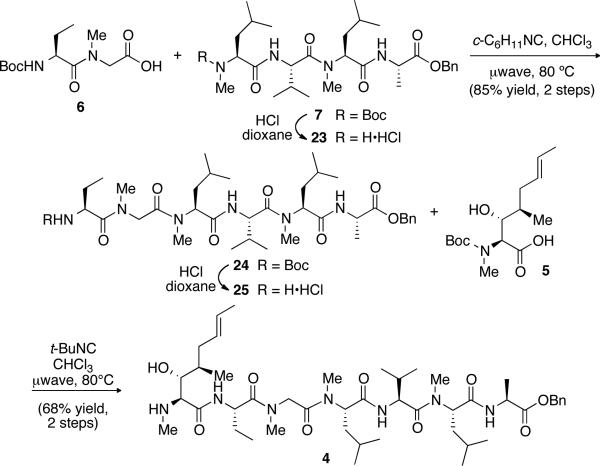

With the required fragments assembled, we now sought to link them together to complete the synthesis of cyclosporin A. In our previous synthesis, a segment coupling between the thioacid analog of dipeptide 6 and tetrapeptide 23 provided hexapeptide 24 in 63% yield under Type IIb conditions.7l We found, however, that hexapeptide 24 could be obtained in significantly higher yield (85% from 7) by merging acid 6 and tetrapeptide 23 in the Type IIa mode under microwave irradiation at 80 °C (Scheme 6). The subsequent joining of fragment 5 to hexapeptide 25 was also achieved by employing a Type IIa reaction. Thus, microwave irradiation of the protected MeBmt residue 5 and hexapeptide amine salt 25 at 80 °C in the presence of t-butyl isonitrile provided the desired heptapeptide 4 in 68% yield over two steps. To our surprise, the coupling was accompanied by concomitant loss of the Boc group. Possibly, cleavage of the urethane function could have been facilitated by intramolecular hydrogen bonding with the neighboring free alcohol at the elevated temperatures induced by microwave heating. Alternatively, once amino acid 5 is activated by FCMA formation, it could undergo cyclization to form the N-carboxyanhydride with formal loss of t-butyl cation. The observed product could have arisen by aminolysis of the cyclic anhydride with 25. The precise mechanism remains unclear.

Scheme 6.

Construction of heptapeptide 4.

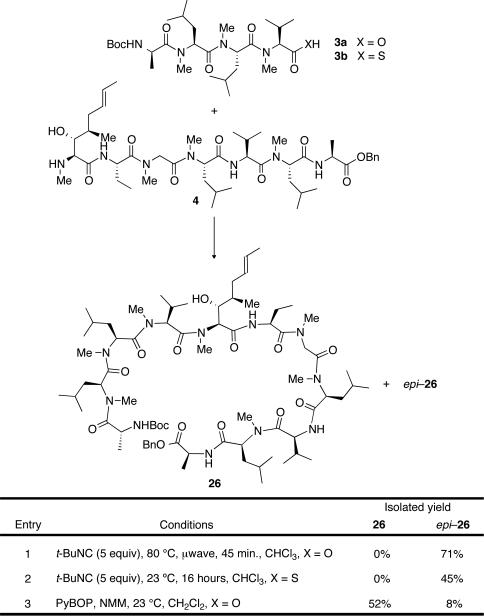

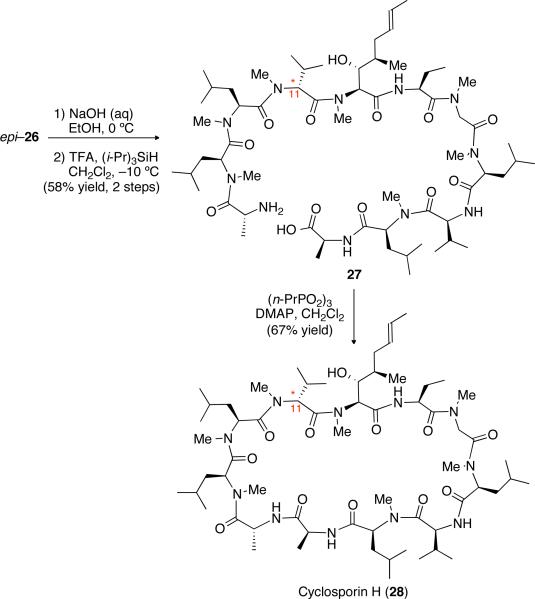

The stage seemed well set for our proposed isonitrile-based coupling of tetrapeptide 3 and heptapeptide 4 (Scheme 7). In the event, carboxylic acid 3a and amine 4 were heated at 80 °C under microwave irradiation in the presence of t-butyl isonitrile. One major product of correct mass was isolated in 71% yield (Scheme 7, entry 1). Surprisingly, this material did not co-elute when co-injected on the HPLC with the linear undecapeptide that we synthesized 71 via PyBOP coupling as described in our previous report. Instead, it co-eluted with the minor product of the PyBOP coupling, which we tentatively had assigned as the epimer of 26 at the α-carbon of MeVal(11) (epi-26). Running the isonitrile coupling with thioacid 3b at room temperature did not ameliorate the problem, as again the major product was still epi-26 (Scheme 7, entry 2). Our initial structural assignment for this product (epi-26) was confirmed by carrying it through the three-step sequence of saponification, removal of the N-terminal carbamate (→27), and macrocyclization using the mixed phosphonic anhydride method20 employed by Wenger12c (Scheme 8). The compound so obtained (28) exhibited chromatographic and spectroscopic properties matching an authentic natural sample of [d-MeVal(11)]-cyclosporin A, better known as cyclosporin H.21,22

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of undecapeptide 26.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of cyclosporin H.

Although we anticipated that we might suffer some loss of diastereomeric integrity at this stage due to oxazolonium ion formation23 during the coupling, the nearly complete epimerization that actually occurred had not been expected. In retrospect, this behavior is in line with what Wenger observed in his attempts to synthesize 2612c. While Wenger's coupling of 3a and 4 using PyBOP gave the correct undecapeptide, he noted that when pivalic anhydride was used as the activating agent the reaction afforded only epi-26, as we found here. Moreover, when Wenger conducted the PyBOP coupling with epi-3a12b (i.e., with d-MeVal at the C-terminus), he still obtained mainly the desired undecapeptide 26 and virtually no d-MeVal–containing isomer. Taken together, these data indicate that a kind of dynamic kinetic resolution is operative, and that there is a different selectivity for formation of 26 versus epi-26 depending on the choice of coupling agent.24 Wenger concluded that this outcome must reflect differences in the activated species that arise by each reagent. Our results suggest that isonitrile-based activation falls within the more “anhydride-like” manifold, not surprisingly, given the highly active acyl donor character of the presumed FCMA intermediate. Indeed, when we attempted the microwave-mediated coupling of epi-3a with 4 using t-butyl isonitrile, the only product formed was again epi-26. Subsequent efforts to overturn the selectivity by adding HOBt and converging on an intermediate in common with PyBOP proved unfruitful. Therefore, the condensation between fragment 3a and heptapeptide 4 was carried out in the presence of PyBOP and NMM in CH2Cl2 to afford the desired (pre-cyclosporin A) undecapeptide 26 in 52% yield (Scheme 7, entry 3).71,22

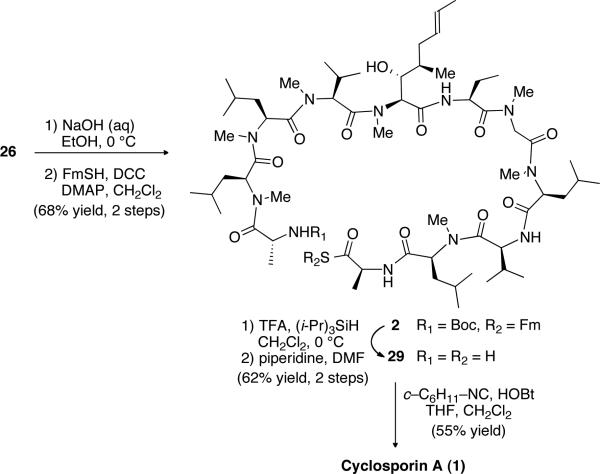

Previously, our group disclosed a method by which the final macrocyclization could be accomplished at 70 °C in 30% yield via isonitrile-based technology under microwave mediation.71 The yield was improved to 54% by addition of HOBt, possibly due to interception of the FCMA intermediate by HOBt, rendering side-product formation by [1,3]-O→N acyl transfer or FCMA hydrolysis less likely. While this was a substantial improvement, we surmised that the elevated temperatures could also be responsible for eroding the yield via decomposition of the starting material and/or product. Inspired by our earlier findings in this area, we sought to perform this macrolactamization at room temperature by employing a C-terminal thioacid rather than a C-terminal carboxylic acid. Saponification of 26 followed by coupling with FmSH in the presence of DCC and DMAP furnished the desired undecapeptide thioester 2 in 68% yield over two steps without apparent epimerization (Scheme 9).22 Unmasking of the N-terminus under acidic conditions was followed by treatment with piperidine in DMF to afford the corresponding thioacid 29 in 62% yield over two steps. Happily, exposure of the unprotected undecapeptide thioacid 29 to 10 equivalents of cyclohexyl isonitrile in the presence of HOBt at room temperature resulted in nearly complete conversion to cyclosporin A (1) after 10 hours, with minimal formation of byproducts. Efforts to purify the final compound were somewhat complicated by significant chromatographic tailing, which led to poor recovery from the stationary phase. Nevertheless, the desired macrocycle was isolated by normal phase HPLC in 55% yield.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of cyclosporin A by Type IIb macrocyclization.

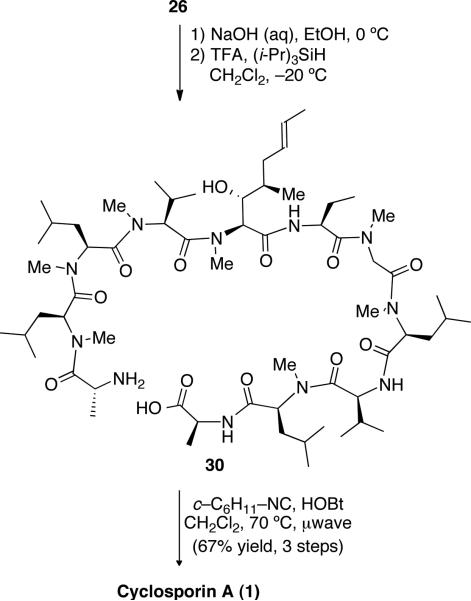

While the Type IIb cyclization did indeed proceed at ambient temperature, the over all yield from 26 was lower than what was previously obtained71 using the Type IIa cyclization, due to the manipulations that were required to install the C-terminal thioacid. Thus, it was synthetically more expedient to complete the synthesis according to the previously determined endgame (Scheme 10). We were pleased to obtain an improved yield over the final three steps (67% versus 54%)71 by incorporating a simple ether rinse to partially purify intermediate 30 prior to the final macrocyclization.22 In the event, the Type IIa macrolactamization proceeded without the formation of detectable byproducts, allowing the desired compound to be isolated in high purity by simple flash chromatography. The characterization data for our synthetic cyclosporine were fully consistent with an authentic sample of natural cyclosporine, as well as with published values.71,11a,12c

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of cyclosporin A by Type IIa macrocyclization.

Two additional points regarding the remarkable transformation of 30 to the final target 1 are worthy of note here. First, the reaction is very sensitive to the steric properties of the mediating isonitrile. While cyclohexyl isonitrile proved exceedingly capable in the cyclization, t-butyl isonitrile failed resoundingly, yielding only a trace of product. This trend is certainly not the case for typical Type II reactions. Indeed, in other cases (vide supra), the use of t-butyl isonitrile afforded the highest yields. Though the reasons for this striking difference in reactivity are still not fully explained, we offer this observation for its potential usefulness to future practitioners of this chemistry: sterically demanding Type II couplings can sometimes be enabled by a less hindered isonitrile.

Furthermore, there does appear to be something unique about 30 as a macrocyclization substrate. In our previous report,71 we surmised that the substrate pre-organization proposed by Wenger12c facilitated the mild conversion of the seco-acid to cyclosporin A using our chemistry. To test whether perturbing the stereochemistry of the substrate would have an effect on our isonitrile-mediated macrocyclization, we subjected 27—the Val(11) epimer of 30—to the same Type IIa conditions. We were able to isolate a product in 41% yield with a mass corresponding to the expected product, cyclosporin H (28), but to our surprise, the 1H NMR spectrum did not match that of the natural sample.22 Since we are very confident in our structural assignment of epi-26 (the precursor to 27, vide supra), we can only surmise that another epimerization event occurred, this time at the C-terminal l-Ala(7) residue, prior to cyclization. While further studies would be required to rigorously assign the structure as [d-Ala(7),d-MeVal(11)]-cyclosporin A, it is interesting to speculate on the implications of the experiment for the mechanism of 30→1 if indeed the C-terminus is prone to epimerization. The fact that we cleanly obtain cyclosporine and not epi-cyclosporine in the case of 30 may simply reflect a kinetic advantage induced by substrate pre-organization that enables macrolactamization to proceed at a faster rate than C-terminal epimerization. By contrast, 27, which may lack this predisposition for cyclization, undergoes prior epimerization at Ala(7) via its epimerization-prone FCMA. Supporting this proposition is our observation that, when the less epimerization-prone phosphonic anhydride method is used to a ffect the cyclization of 27, cyclosporin H(28) is indeed obtained (vide supra, Scheme 8). This explanation is at least consistent with our qualitative observation that the Type IIa macrolactamization of 27 requires more time to proceed to complete conversion than 30.

There is a second possibility that may be relevant, especially in light of our experience with the coupling of 3 and 4. The rate of C-terminal epimerization under Type II conditions may in fact be much faster than the rate of macrolactamization for both 30 and 27. In the case of 30, however, substrate pre-organization may enable l-Ala(7)-30 to cyclize faster than d-Ala(7)-30. Such a dynamic kinetic resolution would imply that the “ faithful” conversion of 30 to cyclosporin A (1) may not reflect any stereochemical vigilance on the part of the putative FCMA or HOBt intermediates. It may instead reflect a proclivity of the substrate to cyclize onto the l-rather than d-Ala(7)-activated ester, as a consequence of pre-organization.

Conclusion

In summary, the utility of isonitriles in forming various amide and peptidic bonds has been well demonstrated in this second generation total synthesis of cyclosporin A. Construction of each of the secondary and tertiary amide linkages was accomplished with good efficiency, although the 4+7 coupling of 3 and 4 under these conditions led to inversion at position 11 to the d-amino acid . Most impressively, the final macrocyclization was achieved with high efficiency using isonitrile chemistry. Another important finding concerned the final macrolactamization step. In the pre-cyclosporine series, which manifests a high level of pre-organization, cyclization occurs smoothly to provide the spectroscopically well-ordered 1. In the case of the d-MeVal(11) system 27 derived from epi-26, cyclization does not seem to benefit as much from pre-organization. Depending on the conditions, this ring closure can provide either cyclosporin H (i.e. [d-MeVal(11)]-cyclosporin A) or under epimerization-prone FCMA conditions, a new cyclosporin, tentatively assigned as the [d-Ala(7), d-MeVal(11)] compound. Neither cyclosporin H nor the [d-Ala(7), d-MeVal(11)] cyclosporin exhibit well-ordered structures at room temperature by NMR criteria. It is interesting to note that the relative configurations at the α-stereocenters needed for rapid macrolactam formation resulting in a well-ordered molecule may correlate well with the bioactivity of the resultant product.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful for support from the NIH (CA28824 to S.J.D., 1F32CA142002-01A1 and K99GM097095-01 to J.L.S.) and the American Cancer Society (PF-11-014-01-CDD to P.K.P.), spectroscopic assistance from Dr. George Sukenick, Hui Fang, and Sylvi Rusli of SKI's NMR core facility, and Laura Wilson and Rebecca Wilson for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Dr. Ping Wang is thanked for the gift of compound 15. We also thank Professor Gregory Verdine of Harvard University for first calling our attention to the cyclosporin problem in the context of isonitriles.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT General experimental procedures, including spectroscopic and analytical data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

REFERENCES

- 1.a Nilsson BL, Soellner MB, Raines RT. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2005;34:91–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kimmerlin T, Seebach D. J. Peptide Res. 2005;65:229–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2005.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dawson P. In: Chemical Biology: From Small Molecules to Systems Biology and Drug Design. Schreiber SL, Kapoor TM, Wess G, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. pp. 567–592. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Montalbetti CAGN, Falque V. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:10827–10852. [Google Scholar]; b El-Faham A, Albericio F. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6557–6602. doi: 10.1021/cr100048w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.See : Albericio F, Bofill JM, El-Faham A, Kates SA. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:9678–9683. references therein.

- 4.Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphrey JM, Chamberlin AR. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:2243–2266. doi: 10.1021/cr950005s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee J, Gilon C, Hoffman A, Kessler H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1331–1342. doi: 10.1021/ar8000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Li X, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5446–5448. doi: 10.1021/ja800612r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jones GO, Li X, Hayden AE, Houk KN, Danishefsky SJ. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4093–4096. doi: 10.1021/ol8016287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li X, Yuan Y, Berkowitz WF, Todaro LJ, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13222–13224. doi: 10.1021/ja8047078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li X, Yuan Y, Kan C, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13225–13227. doi: 10.1021/ja804709s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Li X, Danishefsky SJ. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1666–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Zhu J, Wu X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:577–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wu X, Li X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1523–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Yuan Y, Zhu J, Li X, Wu X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2329–2333. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Wu X, Yuan Y, Li X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:4666–4669. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Stockdill JL, Wu X, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5152–5155. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.06.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Rao Y, Li X, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12924–12926. doi: 10.1021/ja906005j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Wu X, Stockdill JL, Wang P, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4098–4100. doi: 10.1021/ja100517v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Wu X, Park PK, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7700–7703. doi: 10.1021/ja2023898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.We use this term as a mnemonic device to convey the idea that none of the elements of the isonitrile appear in the product, in distinction to the situation in Type I. Of course, the isonitrile becomes the corresponding formamide, which can, in principle, be recycled to regenerate the isonitrile.

- 9.Dreyfuss M, Haerri E, Hofmann H, Kobel H, Pache W, Tscherter H. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1976;3:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Stahelin HF. Experientia. 1996;52:5–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01922409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Heusler K, Pletscher A. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2001;131:299–302. doi: 10.4414/smw.2001.09702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Borel JF. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002;114:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Rüegger A, Kuhn M, Lichti H, Loosli H, Huguenin R, Quiquerez C, von Wartburg A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1976;59:1075–1092. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19760590412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Petcher TJ, Weber H, Rüegger A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1976;59:1480–1488. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19760590509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Wenger RM. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1983;66:2308–2321. [Google Scholar]; b Wenger RM. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1983;66:2672–2702. [Google Scholar]; c Wenger RM. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1984;67:502–525. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For a historical retrospective on the clinical impact of cyclosporine, see: Kahan BD. Transplant. Proc. 2009;41:1423–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.001.

- 14.a Handschumacher R, Harding M, Rice J, Drugge R, Speicher D. Science. 1984;226:544–547. doi: 10.1126/science.6238408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu J, Farmer JD, Jr., Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For a review of the calcium-calcineurin-NFAT pathway, see: Crabtree GR, Olson EN. Cell. 2002;109:S67–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00699-2.

- 16.Evans DA, Weber AE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:6757–6761. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crich D, Sana K, Guo S. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4423–4426. doi: 10.1021/ol701583t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Direct conversion of 3a to 3b results in epimerization of the substrate, presumably at Val(11).

- 19.Confirmation of 18 as the major epimer formed in the 3+1 coupling was accomplished by independent synthesis of 18 via N-terminal extension of 16 using O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU) for the amide bond formations (in modest yields). See the Supporting Information for details.

- 20.Wissmann H, Kleiner H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1980;19:133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traber R, Loosli H, Hofmann H, Kuhn M, Wartburg AV. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1982;65:1655–1677. [Google Scholar]

- 22.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 23.McDermott JR, Benoiton NL. Can. J. Chem. 1973;51:2562–2570. [Google Scholar]

- 24.This hypothesis makes no assumptions regarding the mechanism of epimerization. The equilibration between 3a and epi-3a could occur, in principle, by enolization of the activated carboxylate species or the oxazolonium ion. However, if oxazolonium intermediates are involved, they cannot be the predominant acylating species in both types of couplings (isonitrile and PyBOP); otherwise, both would give the same product. To allow for the observed selectivity differences, there must be a more reactive acyl donor in solution in at least one of the two cases.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.