Abstract

Carbohydrates in various forms play a vital role in numerous critical biological processes. The detection of such saccharides can give insight into the progression of such diseases such as cancer. Boronic acids react with 1,2 and 1,3 diols of saccharides in non-aqueous or basic aqueous media. Herein, we describe the design, synthesis and evaluation of three bisboronic acid fluorescent probes, each having about ten linear steps in its synthesis. Among these compounds that were evaluated, 9b was shown to selectively label HepG2, liver carcinoma cell line within a concentration range of 0.5–10 μM in comparison to COS-7, a normal fibroblast cell line.

Keywords: Boronic acid, carbohydrate, saccharides, antibody mimics, fluorescence, receptor, smart probe, sensor

1. Introduction

Carbohydrates are essential for cell-cell recognition and various biological responses such as inflammation, lymphocyte homing, regulation of metabolic pathways, among others. In addition, the cross-talk between cell surface carbohydrates and cellular receptors has also been associated with the metastatic behavior of various cancer types. Thus far, the detection of the over-expression of such glycoproteins or lipids on membrane surfaces have been accomplished through biological receptors such as antibodies[1,2], aptamers[3,4], peptides or proteins[5], or metabolites[6,7]) linked to a fluorochrome (Fig. 1) allowing the biomarker to be detected by a light source.

Figure 1.

The design of a site-specific fluorescence probe.

Namely, due to their high affinity for their target and/or biomarker of interest, monoclonal antibodies are widely used as biological probes in fluorescence imaging. There are several monoclonal antibodies available for in vivo fluorescence imaging applications, anti-PSMA(prostate specific membrane antigen)[8] labels prostate tumor cells, anti-VEGF(vascular endothelial growth factor) [9] labels tumor cells associated with angiogenesis, and anti-HER-2(human epidermal growth factor recptor-2) [10] labels breast, ovary, and other carcinomas. However, the disadvantages in using monoclonal antibody conjugates as biological imaging probes are contributed to their size. Large biomolecules tend to exhibit lower penetration in tissue of host animal and longer clearance time, allowing background fluorescence interference. Although monoclonal antibodies are engineered genetically near 100% human phenotype, there is always a possibility of eliciting an adverse immunogenic response. There is an evident need to continue the efforts in designing target-specific fluorophores to aid in the detection of tumorigenesis, presence metastasis, and in addition, provide visual guide in the removal of tumor masses.

We are interested in the design and synthesis of small organic molecules with the ability to recognize specific oligosaccharide patterns. Boronic acid moieties, since the 1940’s, have been known to form rapid reversible complexes with 1, 2 and 1,3 cis diols.[11,12,13] Much development has been geared toward sensory design[14,15, 21,22,23,24, 26,27,29,30,31,32,33] and cell labeling[34,35,36] for biological carbohydrates with the use of boronic acid serving as the artificial receptor, which make boronic acid an ideal biological probe for the detection of a cell surface carbohydrates over-expressed on various cancer types. Aryl boronic acid scaffolds targeting cell surface carbohydrates can be considered antibody mimics as they have high affinity and selectivity as antibodies. The advantages of having smaller molecules present creates faster clearance time, higher tissue penetration, and the structural framework can be altered to enhance the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, leading to a more lucrative imaging probe candidate for in vivo applications.

An ideal in vivo biosensor for carbohydrates consists of: (1) a recognition moiety with high affinity and specificity and (2) a spectroscopic reporter, which gives off a measurable signal upon binding. Numerous of peer-reviewed articles have provided insight in the design of biomolecular sensors that contain an ‘on’ and ‘off’ state through a fluorescence quenching mechanism.[37,38,39] This attribute of ‘turning on’ only at the target site has been termed activatable or ‘smart’. Several mentionable molecular quenching mechanisms that have been used in literature are; PET (photoinduced electron transfer), ICT (internal charge transfer), MLCT (metal-ligand charge transfer), and most commonly used in the development of smart probes, FRET (fluorescence resonance electron transfer). The advantages of using molecular fluorescence can be summarized, high sensitivity of detection, and a signal generated only after being bound to the specific biomarker resulting in low to no background noise.

In our initial design an anthracene-boronic acid system (Fig. 2) was chosen as the fluorescent probe. This system was first introduced in 1992 by the Czarnik group, (3, Fig. 3) [40]. In Shinkai system a 1, 5 relationship between an amine and boron was incorporated to create more electron density around the boron center. In doing so, they developed monoboronic acid 1, which is intrinsically selective for fructose and a diboronic derivative also selective for glucose.[41] In this system the amine regulates the fluorescence intensity. The anthracene moiety is quenched by an excited state photoinduced electron transfer(PET), which is considered to be the ‘off’ state of the sensor. Upon addition of a diol, the fluorescence intensity increases, which represent the ‘on’ state of the sensor 2; therefore, creating a smart or ‘activatable’ probe for the detection of cell surface carbohydrates with low background fluorescence. There are two proposed mechanisms in literature that have been introduced as the mechanisms which stop the quenching process of the anthracene motif.[41,42] Shinkai and co-workers proposed that there is a B-N bond formation which stops the quenching process. Upon addition of a diol, leading to the formation of a boronic ester, the pKa of the boron species is decreased. This causes the amine to react with the boron, forming a B-N bond, stopping the quenching process. Later, the Wang group published a paper with detailed experiments providing additional insight as to the mechanism in which the quenching process is eliminated in aqueous medium. They proposed the mechanism is stopped through a hydrolysis mechanism. The B-N bond is labile; as a result it is hydrolyzed. The amine is then protonated, stopping the quenching process.

Figure 2.

Signaling unit for anthracene based photoinduced electron transfer (PET) system.

Figure 3.

Anthracene-based fluorescent chemosensors for saccharides.

When designing a boronic acid scaffold as an artificial probe for a carbohydrate of interest, the appropriate spatial arrangement is imperative for optimal binding[41,45]. In continuing the efforts of developing fluorescent artificial receptors, we have synthesized a series of rigid dianthracene acid compounds. Our goal is to obtain the framework of previously synthesized diboronic acid[46], heteroatom(s) were added within the di-carboxylic acid linker in compound 4 in hopes of increasing the hydrophilicity. The tertiary amine attached to the carbonyl group was changed to a secondary amine to evaluate how a slight change in electronic properties and reduction of a possible steric effect may alter and/or enhance selectivity. With that in place, three di-anthracene boronic acids were synthesized. Since 4 labeled HepG2, hepatocellular liver carcinoma cells, at 1 μM, concentrations between 0.5 and 10 μM were used in fluorescent cell labeling studies. To evaluate the ability of the newly synthesized bisboronic acid derivatives selectively labeling cancer cell only, COS-7, a normal fibroblast mammalian cell line was used in parallel.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Biology

2.1.2 Cell Culture

Cell lines were purchased from ATCC. HEPG2 and COS7 cells were maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum), 1% L-glutamine, and 0.5% gentamicin sulfate (50mg/ml) (MediaTech). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Remaining materials were purchased from Media-Tech unless otherwise noted.

2.1.3 Fluorescent Labeling Studies

HEPG2 and COS7 cells were harvest in six well plates in growth medium until ca. 50% confluency. Cells were then washed with PBS following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 25 min or in 1:1 solution of MeOH/PBS for 25 min. After fixation the cells were washed with PBS twice. Next, 1 ml of 1:1 MeOH/PBS was placed in each well, followed by the desired concentration of anthracene boronic acid derivative (0.5–10 μM). The six well plates were placed at 4°C for 45 min. The cells were viewed with a blue emission filter.

2.1.4 Imaging

Phase contrast and fluorescence overlay images were taken with Carl Zeiss Axiovert 200M by the process imaging software Axiovision with the use of a blue long pass filter (emission wavelength: 397 nm).

2.2 Chemistry

2.2.1 General

All 1H and 13C NMR were recorded at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively, with tetramethylsilane as the internal reference. Elemental and mass spectral analyses were performed at Georgia State University Analytical Facilities. All commercial reagents were used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Acetonitrile (CH3CN) and dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) were distilled from CaH2. Tetrahyrofuran (THF) was distilled from Na and benzophenone.

2.2.2 Fluorescent Binding Studies

A constant concentration of (sensor)bisboronic acid (2 × 10−6 M in MeOH) was mixed with various sugars solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with increasing concentrations at equal volumes. The mixture was allowed to mix for 20 minutes and fluorescence intensity was recorded with a Shimadzu RF-5301PC fluorometer. The fluorescent intensity readings were normalized with the sensor solution only and fitted to non-linear regression (sigmoidal-dose response) curve an overlaid with one-site binding curve (fructose) and two-site binding curve (sorbitol) by the software GraphPrism 4.0. Triplicate measurements were taken and correlation coefficients were ≥ 0.95 for each fit.

2.3 Synthesis and Structural Analysis

2.3.1 Preparation of (10-Azidomethyl-anthracen-9-ylmethyl)-methyl-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (6)

Triphenylphosphine (717 mg, 2.74 mmol), carbon tetrachloride (1 ml), and 2 ml of dry DMF were added to a round bottom flask followed by alcohol derivative 5 (300 mg, 0.856 mmol, in 3 ml of dry DMF). After disappearance of 5 as monitored by TLC, sodium azide (208 mg, 3.16 mmol) was added. The reaction was allowed to stir at room temperature until completion as indicated by TLC and GC-MS analysis. Ice water (10 ml) was added to reaction and the reaction mixture was stirred for 5 min. Then the reaction solution was diluted with ether (50 ml). The organic layer was washed (2 × 10ml) with water and brine, dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash chromatography with ethyl acetate/hexanes (15:85) to produce a yellow oil, (277mg, 90% yield).

1H NMR(CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ: 8.52-8.36 (m, 4H), 7.64-7.59 (m, 4H), 5.57 (s, 2H), 5.37 (s, 2H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 9H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): 155.8, 131.0, 130.4, 127.1, 126.5, 126.1, 126.0, 125.1, 124.3, 79.9, 46.5, 42.7, 31.8, 28.5; ESI MS: [M+(Na)] calculated 400.2, found 400.1.

2.3.2 Preparation of (10-Aminomethyl-anthracen-9-ylmethyl)-methyl-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (7)

Compound 6 (154 mg, 0.410 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (268 mg, 1.02 mmol) in aqueous THF (1:100) was stirred at RT for 16 h. The solution was then concentrated and purified by means of flash chromatography with CH2Cl2/MeOH (90:10) to give 122 mg of a yellow solid, 85% yield. 1H NMR(CDCl3, 400MHz) δ: 8.45-8.38 (m, 4H), 7.57-7.52 (m, 4H), 5.50 (s, 2H), 4.83 (s, 2H), 2.47 (s, 3H), 1.55 (s, 9H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 155.8, 135.8, 131.2, 129.0, 128.5,125.8, 125.7, 125.1, 124.5, 79.7, 42.5, 38.4, 31.7, 28.5; MS(EI) calculated 350, found 350.

2.3.3 General procedure for preparation of Boc-protected diamides (8)

The di-acid (0.543 mmol, 1 equivalent), N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt, 1.9 mmol, 1.47 mg), 1-(2-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide (EDCI, 1.07 mmol, 213 mg), and then compound 7 (1.14 mmol, 400 mg) was added to round bottom flask, followed by the addition of 30 ml of dry CH2Cl2. The solution was allowed to mix for 30 min at 0° C, then triethylamine (TEA) was added to obtain a slight basic solution. Then the reaction temperature was slowly raised to room temperature and allowed to stir for 18 hr. The reaction mixture was washed with 5% sodium bicarbonate (10 ml), 5% citric acid (10 ml), and brine (10 ml). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, gravity filtered, and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography with CH2Cl2/MeOH or precipitation from CH2Cl2/Hexanes.

[10-({[4-({10-[(tert-Butoxycarbonyl-methyl-amino)-methyl]-anthracen-9-ylmethyl}-methyl-carbamoyl)-benzoyl]-aminomethyl)-anthracen-9-ylmethyl]-methyl-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (8a). 80% yield. 1H NMR(CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ: 8.49-8.39 (m, 8H), 7.70-7.59 (m, 8H), 7.70-7.69 (s, 12H), 5.64 (s, 4H), 5.54 (s, 4H), 2.49 (s, 6H), 1.57 (s, 18H).

[10-({[4-({10-[(tert-Butoxycarbonyl-methyl-amino)-methyl]-anthracen-9-ylmethyl}-methyl-carbamoyl)-pyridine-2-carbonyl]-aminomethyl)-anthracen-9-ylmethyl]-methyl-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (8b). 60% yield. 1H NMR(CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ: 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.42-8.40 (m, 2H), 8.35-8.31 (m,6H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.53-7.44 (m, 8H), 5.58 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 2H), 5.45 (s, 4H), 5.31 (s, 2H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 6H), 1.51 (s, 18H).

[10-({[4-({10-[(tert-Butoxycarbonyl-methyl-amino)-methyl]-anthracen-9-ylmethyl}-methyl-carbamoyl)-pyrazine-2-carbonyl]-aminomethyl)-anthracen-9-ylmethyl]-methyl-carbamic acid tert-butyl ester (8c). 50% yield 1H NMR(CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ: 9.22-9.20 (m, 1H), 8.51-8.40 (m, 8H), 8.05-8.04 (m, 1H), 7.2-7.56 (m, 8H), 5.67 (s, 4H), 5.54 (s, 4H), 2.52 (s, 6H), 1.66 (s, 18H).

2.3.4 General procedure for preparation of diboronic acids (9)

Deprotection of the amine moiety of diamide 8 was accomplished by dissolving it in dry CH2Cl2 (15 ml) followed by trifluoroacetic acid addition and stirring at room temperature 15 min. After removal of Boc-protected group, the residue was concentrated and dried in vacuo for 3 hr. The reaction mixture was then subsequently placed in a round bottom flask. Then dry acetonitrile (35 ml), potassium carbonate (2.2 mmol, 305 mg), catalytic amount of potassium iodide, and compound 10 (0.88 mmol, 251 mg) were added to the same flask. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 18h. The insoluble materials were filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The resulting residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2, 20 ml of 10% sodium bicarbonate, and 8 ml of water for the removal of protecting group of the boronate motif. The mixture was stirred for 4h. The organic phase was washed with brine and dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude material was precipitated from THF/Hexanes.

Diboronic acid (9a). 28% yield. 1H NMR(CD3OD + CDCl3, 400MHz) δ: 8.56-8.54 (m, 4H), 8.37 (m, 4H), 7.62-7.56 (m, 12H), 7.38-7.31 (m, 8H), 5.38 (s, 4H), 5.03 (s, 4H), 4.37 (s, 4H), 2.42 (s, 6H); HRMS(+H/D)[-H2O] calculated 882.4124, found 882.4105.

Diboronic acid (9b). 25% yield. 1H NMR(CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ: 8.71-8.70 (m, 1H), 8.51-8.49 (m, 4H), 8.46-8.44 (m, 4H), 8.24-8.19 (m, 1H), 7.69-7.66 (m, 2H), 7.57-7.51 (m, 9H), 7.37-7.32 (m, 4H), 7.29-7.26 (m, 2H), 5.59 (s, 1H), 5.54 (s, 1H), 5.49 (s, 2H), 5.00 (s, 4H), 4.31 (s, 4H), 2.38 (s, 6H). HRMS(+H)[-H2O] calculated 882.3997, found 882.4001.

Diboronic acid (9c.) 20% yield. 1H NMR(CD3OD, 400MHz) δ: 9.09 (s, 2H), 8.53-8.51 (m, 4H), 8.25-8.23(m, 4H), 7.71-7.69 (m, 2H), 7.60-7.52 (m, 8H), 7.37-7.33 (m, 4H), 7.30-7.28 (m, 2H), 5.60 (s, 4H), 5.49 (s, 4H), 4.29 (s, 4H), 2.37 (s, 6H). HRMS(+H) [-H2O] calculated 883.3951, found 883.3978.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Synthesis of Artificial Receptors

The preparation of a dianthracene boronic acid for the development of a fluorescent probe for biological saccharides begin with 5, which was prepared from a previous published paper.[44] The hydroxyl moiety of 5 was converted to an azide to give 6 in 90% yield using a mild Mitsunobu type reaction.[47] The reduction of the azide was achieved by the addition of triphenylphosphine in aqueous THF to generate amine 7 in 81% yield. The amidation reaction of 7 with various di-acids was performed by treatment with 1-(2-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) along with N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) to afford compounds 8a–c in 50–60% yield. After deprotection of derivatives 7 with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), the unprotected free amines were then reacted with aryl boronic ester 10[41] in the presence of potassium carbonate with a catalytic amount of potassium iodide. Then deprotection of the boronate produced compounds (9a–c, Scheme 1) in yields of 15–30%.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of bis-anthracene boronic acid derivatives.

(a) DMF, PPh3, CCl4, NaN3, RT; 90%; (b) (aq.) THF, PPh3, RT; 85%; (c) CH2Cl2, DMF, EDCI, HOBt, TEA, HOOCRCOOH, 0°C→RT; 50–80%; (d) i. TFA, CH2Cl2, ii. K2CO3, cat. KI, CH3CN, 10, iii.10%NaHCO3, CH2Cl2, H2O, RT; 15–30%.

3.2 Determination of Binding Constants

To validate the complexation of the synthesized boronic acids and diol, various biological sugars were used to obtain the apparent binding constant. Briefly, 2 ml of sensor solution in MeOH was mixed with 2 ml of aqueous phosphate buffer solution containing saccharide of interest with increasing concentration. Next, the fluorescent intensity was obtained, and normalized by sensor solution only. As shown in Figure 4, there is a fluorescent intensity increase with increasing concentration of carbohydrate. The apparent binding constants are displayed in Table 1, as shown there is a low binding affinity for glucose with each di-boronic acid. However there is a higher binding affinity for sugars that bind to boronic acids in a trivalent fashion, such as fructose and sorbitol.[48] The binding constants for fructose are 9c(504M−1) > 9b(266M−1) > 9a(212M−1) respectively. Compound 9c showed the highest binding affinity for fructose; therefore sorbitol was tested with this compound only, showing a binding affinity of 1051 M−1. Such results show a pattern for the binding of monoboronic acids[10], one could possibly state that 9c displays a two-binding site model between the interactions of hydroxyl groups of the saccharide (substrate) and the bisboronic acid units (receptor).

Figure 4.

a.) Fluorescence intensity changes (I/I0) of 9c as a function of sugar concentration at room temperature: 1.0 × 10−6 M in 50% MeOH/0.1 M aqueous phosphate buffer at pH 7.4: λex = 370 nm, λem= 423 nm.

Table 1.

Binding Constants for the complex of sensor and saccharide.

| Sensors | Ka(M−1) fructose | Ka(M−1) glucose | Ka(M−1) sorbitol |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9a | 212 | 28 | ___a |

| 9b | 266 | 1 | ___a |

| 9c | 504 | 2 | 1051 |

Ka values were obtained using a non-linear regression curve fitting with the software GraphPad Prism 4.0.

Binding constant not determined.

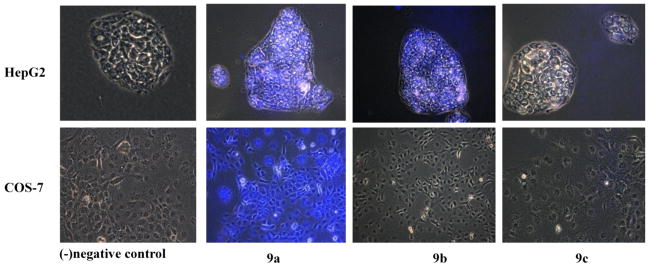

3.3 Evaluation of Fluorescent Labeling Studies

To explore the capability of the bisboronic acids labeling carcinoma cell lines, we studied their ability to stain HepG2, liver carcinoma cells as oppose to a normal fibroblast cell line, COS-7.[44] Briefly, cells were cultured in six-well plates with 1 × 106 M per well and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 48 h. The media was then removed and cells were washed with PBS. The cells were fixed with methanol/PBS. After fixation, cells were washed twice with PBS. The bis-anthracene boronic acids at 0.5–10 μM were added to each well that contained 1 ml of 1:1 MeOH/PBS, and incubated for 45 min at 4 °C. The staining of the fluorescent probes was observed using a fluorescent microscope with a blue optical filter. Images were shown as overlay images of phase contrast and fluorescent microscopy. In this way, the non-labeled cells appear as a gray scale image and labeled cells are blue in color. The staining results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Fluorescent labeling studies of a liver carcinoma cell line HepG2 and a normal fibroblast mammalian cell line COS-7 with compounds 9a–c. The negative control contains buffer only.

Bisboronic acids 9a and 9b stained the HEPG2 cell line at similar concentration, 1μM. However, 9a as well stained COS-7 cell line, diminishing the selectivity of the lead compound 4 toward hepatocellular carcinoma line versus normal fibroblast cells. The pyrazine compound 9c at concentrations between 0.5–10 μM showed weak or no binding affinity for either cell line.

4. Conclusion

Three dianthracene diboronic acids were synthesized and evaluated for the labeling of liver carcinoma cell line, HepG2 as oppose to a normal mammalian fibroblast cell line, COS-7. Compound 9b showed similar staining concentration compared to model compound 4. However 9a, the removal of the methyl group from the amino group attached to the linker, seemed to diminish the selectivity. Compound 9c showed weak or no selectivity for either cell line. One could speculate that there are physiochemical parameters governing non-labeling for either cell line of compound 9c. However it is beyond the scope of this article, additional studies are underway.

Aforementioned, there is an increasing need to design recognition moieties to be used as diagnostic tools to monitor the presence of certain oligosaccharides as they are associated with the progression and the metastatic behavior of certain cancer and tumor cell types. With the appropriate fluorescent boronic acid scaffold to detect these oligosaccharides one could begin to design boronic acid moieties as antibody mimics to serve as tumor-specific fluorphores to pursue the effector mechanisms that govern the pathogenesis of cancer and as well provide image-guided tumor resection. The design of such small organic probes could aid in the longevity of cancer patients and decrease the morbidity that is associated with later stage of cancer through early detection. With that said, additional exploratory computational and/or molecular modeling design could aid in the discovery of boronic acids with the appropriate scaffold to serve as antibody mimics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support in our lab by the National Institutes of Health (NO1-CO-27184, CA88343, and CA113917), the Georgia Cancer Coalition through a Distinguished Cancer Scientist Award, and the Georgia Research Alliance through an Eminent Scholar endowment and a Challenge grant. We also would like to give special thanks to Shafiq Khan and lab members at Clark Atlanta University for the use of his cell culture lab. Dr. Binghe Wang at Georgia State University, Dr. Irene Lee at Case Western Reserve University for the helpful suggestions and critiquing of this manuscript, and GAANN fellowship through Georgia State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaushal S, McElroy MK, Luiken GA, Talamini MA, Moossa AR, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorophore-conjugated anti-CEA antibody for the intraoperative imaging of pancreatic and colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1938–1950. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0581-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folli S, Westermann P, Braichotte D, Pelegrin A, Wagnieres G, van den Bergh H, Mach JP. Antibody-indocyanin conjugates for immunophotodetection of human squamous cell carcinoma in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2643–2649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lupold SE, Hicke BJ, Lin Y, Coffey DS. Identification and characterization of nuclease-stabilized RNA molecules that bind human prostate cancer cells via the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4029–4033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira CS, Papamichael K, Guilbault G, Schwarzacher T, Gariepy J, Missailidis S. DNA aptamers against the MUC1 tumour marker: design of aptamer-antibody sandwich ELISA for the early diagnosis of epithelial tumours. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;390:1039–1050. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veiseh M, Gabikian P, Bahrami SB, Veiseh O, Zhang M, Hackman RC, Ravanpay AC, Stroud MR, Kusuma Y, Hansen SJ, Kwok D, Munoz NM, Sze RW, Grady WM, Greenberg NM, Ellenbogen RG, Olson JM. Tumor paint: a chlorotoxin:Cy5.5 bioconjugate for intraoperative visualization of cancer foci. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6882–6888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Ding N, Xu Y, Qu X, Zhang J, Zhao C, Hong L, Lu Y, Xiang G. Folate receptor-targeted quantum dot liposomes as fluorescence probes. J Drug Target. 2009;17:502–511. doi: 10.1080/10611860903013248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamaly N, Kalber T, Thanou M, Bell JD, Miller AD. Folate receptor targeted bimodal liposomes for tumor magnetic resonance imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:648–655. doi: 10.1021/bc8002259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patri AK, Myc A, Beals J, Thomas TP, Bander NH, Baker JR., Jr Synthesis and in vitro testing of J591 antibody-dendrimer conjugates for targeted prostate cancer therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:1174–1181. doi: 10.1021/bc0499127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virostko J, Xie J, Hallahan DE, Arteaga CL, Gore JC, Manning HC. A molecular imaging paradigm to rapidly profile response to angiogenesis-directed therapy in small animals. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:204–212. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda M, Tada H, Higuchi H, Kobayashi Y, Kobayashi M, Sakurai Y, Ishida T, Ohuchi N. In vivo single molecular imaging and sentinel node navigation by nanotechnology for molecular targeting drug-delivery systems and tailor-made medicine. Breast Cancer. 2008;15:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s12282-008-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorand JP, Edwards JO. Polyol complexes and structure of the benzeneboronate ion. J Org Chem. 1959;24:769–774. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springsteen G, Wang B. A Detailed Examination of Boronic Acid-Diol Complexation. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:5291–5300. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan J, Springsteen G, Deeter S, Wang B. The Relationship among pKa, pH, and Binding Constants in the Interactions between Boronic Acids and Diols-It is not as Simple as It Appears. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:11205–11209. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon J, Czarnik AW. Fluorescent Chemosensors of Carbohydrates. A Means of Chemically Communicating the Binding of Polyols in Water Based on Chelation-Enhanced Quenching. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5874–5875. [Google Scholar]

- 15.James TD, Sandanayake KRAS, Iguchi R, Shinkai S. Novel Saccharide-Photoinduced Electron Transfer Sensors Based on the Interaction of Boronic Acid and Amine. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8982–8987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang S, Rusin O, Escobedo JO, Kim KK, Yang Y, Fakode S, Warner IM, Strongin RM. Stereochemical and Regiochemical Trends in the Selective Spectrophotometric Detection of Saccharides. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12221–12228. doi: 10.1021/ja063651p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao H, McGill T, Heagy MD. Substituent Effects on Monoboronic Acid Sensors for Saccharides Based on N-Phenyl-1,8-Naphthalenedicarboximides. J Org Chem. 2004;69:2959–2966. doi: 10.1021/jo035760h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asher SA, Alexeev VL, Goponenko AV, Sharma AC, Lednev IK, Wilcox CS, Finegold DN. Photonic Crystal Carbohydrate Sensors: Low Ionic Strength Sugar Sensing. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3322–3329. doi: 10.1021/ja021037h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duggan PJ, Offermann DA. The Preparation of Solid-supported Peptide Boronic Acids Derived from 4-borono-L-phenylalanine and their Affinity for Alizarin. Aust J Chem. 2007;60:829–834. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamsey S, Suri JT, Wessling RA, Singaram B. Continuous Glucose Detection using Boronic Acid-substituted Viologens in Fluorescent Hydrogels: Linker Effects and Extension to Fiber Optics. Langmuir. 2006;22:9067–9074. doi: 10.1021/la0617053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang TZ, Anslyn EV. A Colorimetric Boronic Acid Based Sensing Ensemble for Carboxy and Phospho Sugars. Org Lett. 2006;8:1649–1652. doi: 10.1021/ol060279+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan W, Zhang DQ, Wang Z, Liu CM, Zhu DB. 4-(N,N-dimethylamine)benzonitrile (DMABN) Derivatives with Boronic Acid and Boronate Groups: New Fluorescent Sensors for Saccharides and Fluoride Ion. J Mater Chem. 2007;17:1964–1968. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monzo A, Bonn GK, Guttman A. Boronic Acid-lectin Affinity Chromatography. 1. Simultaneous Glycoprotein Binding with Selective or Combined Elution. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;389:2097–2102. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1627-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolini J, Testoni FM, Schuhmacher SM, Machado VG. Use of the Interaction of a Boronic Acid with a Merocyanine to Develop an Anionic Colorimetric Assay. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3467–3470. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu SQ, Bakovic L, Chen AC. Specific Binding of Glycoproteins with Poly(aniline boronic acid) Thin Film. J Electroanal Chem. 2006;591:210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trupp S, Schweitzer A, Mohr GJ. Fluororeactands for the Detection of Saccharides based on Hemicyanine Dyes with a Boronic Acid Receptor. Microchimica Acta. 2006;153:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C, Suslick KS. Syntheses of Boronic-acid-appended Metal Loporphyrins as Potential Colorimetric Sensors for Sugars and Carbohydrates. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 2005;9:659–666. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, Lee MC, Sartain F, Pan X, Lowe CR. Designed Boronate Ligands for Glucose-selective Holographic Sensors. Chemistry. 2006;12:8491–8497. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James TD. Saccharide-selective Boronic Acid based Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) Fluorescent Sensors. Creative Chemical Sensor Systems. 2007:107–152. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cambre JN, Roy D, Gondi SR, Sumerlin BS. Facile Strategy to Well-defined Water-soluble Boronic Acid (Co)Polymers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10348–10349. doi: 10.1021/ja074239s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu SQ, Wollenberger U, Katterle M, Scheller FW. Ferroceneboronic Acid-based Amperometric Biosensor for Glycated Hemoglobin. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2006;113:623–629. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badugu R, Lakowicz JR, Geddes CD. Wavelength-ratiometric near Physiological pH Sensors based on 6-aminoquinolinium Boronic Acid Probes. Talanta. 2005;66:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong AJ, Yamauchi A, Hayashita T, Zhang ZY, Smith BD, Teramae N. Boronic Acid Fluorophore/beta-Cyclodextrin Complex Sensors for Selective Sugar Recognition in Water. Anal Chem. 2001;73:1530–1536. doi: 10.1021/ac001363k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnett TJ, Peebles HC, Hageman JH. Synthesis of a Fluorescent Boronic Acid which Reversibly Binds to Cell Walls and a Diboronic Acid which Agglutinates Erythrocytes. Biochem Biophy Res Comm. 1980;96:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang W, Gao S, Gao X, Karnati VR, Ni W, Wang B, Hooks WB, Carson J, Weston B. Diboronic Acids as Fluorescent Probes for Cells Expressing Sialyl Lewis X. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:2175–2177. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang W, Fan H, Gao S, Gao X, Ni W, Karnati V, Hooks WB, Carson J, Weston B, Wang B. The First Fluorescent Diboronic Acid Sensor Specific for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Expressing Sialyl Lewis X. Chem Biol. 2004;11:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A., Jr In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:375–378. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood U, Tung CH, Bogdanov A, Jr, Weissleder R. Near-infrared optical imaging of protease activity for tumor detection. Radiology. 1999;213:866–870. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi H, Ogawa M, Alford R, Choyke PL, Urano Y. New strategies for fluorescent probe design in medical diagnostic imaging. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2620–2640. doi: 10.1021/cr900263j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon J, Czarnik AW. Fluorescent chemosensors of carbohydrates. a means of chemically communicating the binding of polyols in water based on chelation-enhanced quenching. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5874–5575. [Google Scholar]

- 41.James TD, Sandanayake KRAS, Iguchi R, Shinkai S. Novel saccharide-photoinduced electron transfer sensors based on the interaction of boronic acid amine. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8982–8987. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni W, Kaur G, Springsteen G, Wang B, Franzen S. Regulating the fluorescence intensity of an anthracene boronic acid system: B-N bond or a hydrolysis mechanism? Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;32:571–581. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang W, Gao S, Gao X, Karnati VVR, Ni W, Wang B, Hooks WB, Carson J, Weston B. Diboronic acids as fluorescent probes for cells expressing sialyl lewis X. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2002;12:2175–2177. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang W, Fan H, Gao X, Gao S, Karnati VVR, Ni W, Hooks B, Carson J, Weston B, Wang B. The first fluorescent diboronic acid sensor specific for hepatocellular carcinoma cells expressing sialyl lewis X. Chem & Bio. 2004;11:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karnati VV, Gao X, Gao S, Yang W, Ni W, Sankar S, Wang B. A glucose-selective fluorescence sensor based on boronic acid-diol recognition. Bioorg & Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:3373–3377. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang W, Fan H, Gao X, Gao S, Karnati VV, Ni W, Hooks WB, Carson J, Weston B, Wang B. The first fluorescent diboronic acid sensor specific for hepatocellular carcinoma cells expressing sialyl Lewis X. Chem Biol. 2004;11:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin Y, Lang SA, Seifert CM, Child RG, Morton GO, Fabio PF. Aldehyde syntheses. Study of the preparation of 9,10-anthracenedicarboxaldehyde. J Org Chem. 1979;25:4701–4705. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Norrild JC. An illusive chiral aminoalkylferroceneboronic acid. Structural assignment of a 1:1 sorbitol and new insight into boronate-polyol interactions. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2. 2001;2:719–726. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.