Abstract

We report 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations, at various temperatures, of sucrose in water (with concentrations of sucrose ranging from 0.02 to 4 M), and in a 7:3 water-DMSO mixture. Convergence of the resulting conformational ensembles was checked using adaptive-biased simulations along the glycosidic φ and ψ torsion angles. NMR relaxation parameters, including longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates, nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOE), and generalized order parameter (S2) were computed from the resulting time-correlation functions. The amplitude and time scales of molecular motions change with temperature and concentration in ways that track closely with experimental results, and are consistent with a model in which sucrose conformational fluctuations are limited (with 80–90% of the conformations having φ – ψ values within 20° of an average conformation), but with some important differences in conformation between pure water and DMSO-water mixtures.

1. Introduction

Static pictures of biological molecules from crystallography provide important information relating structures to biological function. Dynamical information on flexibility or conformation changes in solution also provide information of relevance to enzymatic activity and molecular recognition. The flexibility of carbohydrates in solution has been studied for a long time1–3 and categorized by Bush and coworkers as flexibility due to single free energy minima and changes due to the transitions among different minima.4–8

For investigating conformations of biological molecules in solution, the most useful experimental tools include NMR longitudinal and transverse spin relaxation (R1/R2) and nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOE),9,10 spin-spin coupling constants,11 and residual dipolar couplings (RDCs).12 For the disaccharide sucrose, early experimental data, such as 13 C relaxation parameters in pure water or water-dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO) mixtures,13–17 and residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) in dilute liquid crystal media,18 support a fairly rigid structure (dominated by structures near the crystal conformation); other data, including steady state nuclear Overhauser effects (NOE),7,19 J coupling constants20–22 and RDCs6 point to considerable flexibility in its glycosidic linkage. Moreover, structural data of sucrose in complex with other macromolecules6 show considerable variations in the glycosidic linkage. This suggests that the conformation of sucrose might be subject to environment effects such as temperature and solvent type, as well as binding state.

The interpretation of NMR quantities generally requires structural models and is simplified for models with less flexibility. The available experimental data were performed in different solvation environments such as solvent type (pure water,14,15 water-DMSO mixture,13,16,17 or dilute liquid crystal media6), concentration,14,15,23 and temperature.6,14,15,17 For a nearly rigid molecule, all these experimental data should provide a consistent result. As flexibility increases, the derivation of structure information from NMR values becomes much more difficult. The information derived from different experiments might be not in obvious agreement with each other.

The analysis of NMR relaxation parameters is one attractive way to investigate the conformation flexibility of biological molecules in aqueous solution.24,25,26,27 For example, the model-free approach27 assumes that the reorientation time correlation function of a spin-spin vector can be separated into the internal motion part and the overall rotation one. The flexibility of internal motions is represented by the general order parameter derived from the correlation function of internal motions. NMR relaxation experiments have been reported for many carbohydrates8,28,30,31–34 including sucrose.13–17,23 Low temperature cryosolvents are generally needed to avoid the extreme narrowing regime.35

Molecular dynamics simulation is an alternative for studying conformation flexibility. In principle NMR relaxation parameters can be calculated directly by analyzing snapshots from MD trajectories although significantly long simulations are required.36,37 Recent advances in computing power have made the direct calculations of relaxation parameters from MD trajectories possible.36,38,24 Older MD simulations19,39–46 are not fully consistent with each other. These simulations have trajectories varying from 20 picoseconds to 1 nanosecond. Our companion study47 extends the simulations to 100 nanoseconds with five different water models. In a separate paper,47 we have shown that residual dipolar couplings and indirect spin-spin couplings computed from trajectory snapshots best support a model where the crystal conformation is the dominant one in dilute aqueous solution.

In dilute solution at room temperature, sucrose interconverts among its allowed conformations on sub-nanosecond time scales, so that the sampling seen in 100 ns simulations is nearly converged. This is no longer true at lower temperatures, or at higher concentrations of sugar, or when solvated in liquids with high viscosity. To tackle such sampling problems48–54 more advanced MD techniques have been developed including replica exchange,55 hyperdynamics,56 conformation flooding,57 accelerated molecular dynamics,58 metadynamics,59 adaptive biasing force method60 as well as adaptive biasing potential method (ABMD).61 Although the time scales of conformational transitions can not be directly obtained from these methods, free energy minima, surface and reaction paths can be constructed in a much shorter simulation time scale than with “brute-force” MD methods. The adaptively biased molecular dynamics61 was developed recently and has been implemented in Amber. In the report, we present ABMD simulations for sucrose in explicit water and water-DMSO mixtures, examining the free energy landscape of sucrose in a water-DMSO mixture at low temperatures.

2. Computational Methods

1. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Explicit MD simulations with different water models were performed using the same procedure as described in the previous report.47 We continue to choose the latest GLYCAM 0662 for sucrose in SPC,63 TIP3P,64 TIP4P,65 and TIP4P/Ew66 waters, and its lone-pair counterpart GLYCAM04EP67 for TIP5P waters.68

For the simulations of sucrose at different concentrations, we used the PACKMOL program69 to produce the initial configurations with different number of sucrose molecules mixed with the same number of waters. The number of TIP4P/Ew water molecules was fixed at 2000 and the number of sucrose molecules was set to 4, 18, 36, 72, 108 and 144, roughly corresponding to the concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 mol/L. In addition to the same equilibration runs in NVT (0.5 ns) and NPT (0.5 ns) as the study of different water models, 10 ns NPT equilibration run was done for each concentration before the formal 100 ns NVE production run in order to obtain a well-equilibrated system.

We also used PACKMOL69 to build the system for simulations of sucrose in the 7:3 water-DMSO mixture. The system contains 1 sucrose, 857 DMSOs, and 2000 TIP4P/Ew waters. In general the atomic models of DMSO70 are not so well-developed as water. We used the one compatible with AMBER force field, the all-atom model developed by Kollman and coworkers.71 We performed equilibration runs in 0.5 ns NVT and 10.5 ns NPT before the 100 ns production NVE, and saved the snapshots of trajectories every picosecond.

2. Construction of Free Energy Landscape from Adaptively Biased MD

In a previous paper47 we built free energy landscapes (potential of mean force) via the probability distributions (P(φ, ψ)) from unbiased molecular dynamics trajectories:

| (1) |

where kB is Bolzmann’s constant and T is temperature. For convenience we also shifted all surfaces to make the values of global minima equal to 0.

The assumption of Eq. 1 is that the MD trajectories are long enough to fully sample the relevant phase space, which is a good approximation for systems with low free energy barriers. In a water-DMSO mixture, the sucrose molecule exhibits much slower dynamics and the barriers between free energy minima are much higher. Due to these high barriers, transitions between minima are difficult to observe during the 100 ns normal MD simulations. The adaptively biased molecular dynamics61 is a recent addition to the advanced molecular dynamics techniques for accelerating simulations and is capable of overcoming these high free energy barriers and estimating the potential of mean force in the relevant space.

In the ABMD method, the free energy associated with a reaction coordinate σ (r⃗1, …, r⃗N), a smooth function of the atomic positions, r⃗1, …, r⃗N, is defined as

| (2) |

which is a formal version of Eq. 1.

In order to obtain this free energy surface, ABMD adds a time-dependent potential, which is a function of reaction coordinates such as glycosidic dihedrals in our case, to the normal equations of motions. This biasing potential accelerates the system to escape deep free energy valleys:

| (3) |

where F⃗a represents forces from ordinary MD, the second term on the right are the force derived from the biasing potential U[t|σ(r⃗1, …, r⃗N)], and σ is the value of the reaction coordinate at a given conformation. The biasing potential evolves as

| (4) |

with the initial condition U(t= 0|ξ)= 0. G(ξ) is a positive definite and symmetric kernel, like a smoothed Dirac delta function. τF defines a flooding timescale. For large enough τF and small enough kernel width, the biasing potential U(t|ξ) converges towards –f(ξ) as t → ∞. In real simulations, the choice of τF value is a trade-off between accuracy and simulation time. A large value will improve the accuracy of the estimation but slow down the simulation time to convergence. For our simple disaccharide, τF = 100 ps, the same value used for two prototypical peptides in reference.61 Other simulations of τF = 500 ps and τF = 50 ps produced similar results. In Figures 2S and 3S we show the free energy surface (the negative value of biasing potential) at different times of ABMD flooding simulation. The probabilities within the circle region of 20 degree of four free energy minima are plotted in Figure 3S as the increase of flooding time. We can see that the biasing potential roughly converges at around 12 ns for pure water and 40 ns for water-DMSO mixture.

To improve the accuracy of the free energy surface, the ABMD simulations can be followed by additional simulations that use the final ABMD result as an approximate bias. Barriers between conformations are thus much reduced, allowing estimates to again be made based on Eq. 1. After the biasing potentials become converged (around 12 ns for pure water and 40 ns for water-DMSO mixture, as discussed below), we sampled the ABMD bias on a 2°×2° grid, and interpolated from this to run a final 100 ns simulation.

3. Calculation of Relaxation Parameters

From the simulation trajectories the rotational time correlation function of a 13C–1H pair is defined as37,36

| (5) |

where P2 is the second-order Legendre polynomial, χ is the angle between the inter-spin vector in the laboratory reference frame at time t and t+τ, r(t) is the instantaneous pair distance, and the angle brackets represent a thermal average. Each resulting correlation function can be fit to double-exponential or multi-exponential function. The spectral density function is then obtained by Fourier-transforming the fitted time correlation function:

| (6) |

If the correlation function is fitted to sums of exponentials, then the spectral density becomes a sum of Lorentzian functions:

| (7) |

Relaxation parameters depend on the spectral density functions at the relevant 1H and 13C Larmor frequencies.24,25 The spin-lattice relaxation rate is defined as

| (8) |

where and are the dipolar and chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) components of the spin-lattice relaxation-rate constants, respectively. Similarly, the spin-spin relaxation rate is defined as

| (9) |

where and are the dipolar and CSA components of the spin-spin relaxation-rate constants, respectively.

The dipolar relaxation rates

| (10) |

| (11) |

are the main contributors to the overall relaxation. The constant factor K has the form as

| (12) |

where μ0 is the permeability of free space, Ħ is Planck’s constant, and γH and γC are the gyromagnetic ratios for the nuclei of carbon and hydrogen, and reff is

| (13) |

the appropriately averaged internuclear distance between atoms. We used reff =1.11 Å for C-H vectors in our calculations; this is slightly larger than the equilibrium distance of about 1.09 Å to account for quantum vibrational effects no present in these classical simulations.72

Chemical-shift anisotropy contributions to R1 and R2 are incorporated as below

| (14) |

| (15) |

where Δδ is the chemical shift tensor difference between parallel and perpendicular components, assuming an axially symmetric chemical shift tensor. For sucrose in single-crystal state,73 Δδ varies from 26.8 to 50.5 for different Carbon atoms with a mean of 38.6. In general the chemical-shift anisotropy contributions are very small and can be neglected in our study. For example, the dipolar contribution of C-H4g to R1 is 1.31 sec−1 (Table 2), whereas the CSA contribution (using 25 ppm) is 6.2×10−5 sec−1. If we used a larger value of the CSA (such as 40 ppm) the CSA contribution would only increase to 2.48×10−4 sec,−1 still much smaller than the dipolar contribution.

Table 2.

Relaxation data for Carbon-13 nuclei in sucrose with different water models at T = 300 K and B = 9.4 T. R1, R2 in s−1, τm in ps.

| SPC | TIP3P | TIP4P | TIP4P/Ew | TIP5p | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-H | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 |

| C-H1g | 0.91 | 32.6 | 0.64 | 0.88 | 31.6 | 0.60 | 0.93 | 42.4 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 63.3 | 1.22 | 0.87 | 69.4 | 1.31 |

| C-H2g | 0.93 | 32.3 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 37.1 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 45.9 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 66.3 | 1.28 | 0.90 | 69.0 | 1.32 |

| C-H3g | 0.92 | 31.9 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 35.6 | 0.64 | 0.91 | 46.0 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 65.6 | 1.26 | 0.85 | 72.1 | 1.32 |

| C-H4g | 0.92 | 33.2 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 34.9 | 0.65 | 0.91 | 47.4 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 69.4 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 71.5 | 1.33 |

| C-H5g | 0.93 | 32.6 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 37.3 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 46.0 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 67.4 | 1.30 | 0.88 | 69.8 | 1.32 |

| C-H3f | 0.83 | 38.8 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 33.0 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 47.3 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 68.1 | 1.25 | 0.84 | 63.8 | 1.15 |

| C-H4f | 0.79 | 36.9 | 0.64 | 0.87 | 30.8 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 44.6 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 58.7 | 1.08 | 0.85 | 57.4 | 1.05 |

| C-H5f | 0.90 | 34.7 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 34.1 | 0.65 | 0.86 | 54.2 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 69.6 | 1.30 | 0.83 | 72.9 | 1.29 |

| C-H6g | 0.79 | 29. | 0.50 | 0.77 | 29.4 | 0.49 | 0.81 | 40.2 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 58.0 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 66.2 | 1.12 |

| C-H1f | 0.84 | 28.7 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 27. | 0.49 | 0.83 | 36.7 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 51.1 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 68.6 | 1.18 |

| C-H6f | 0.77 | 26.4 | 0.44 | 0.78 | 25.2 | 0.42 | 0.77 | 34.6 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 47.0 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 50.0 | 0.88 |

| Ringa | 0.89 | 34.2 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 34.3 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 46.7 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 66.1 | 1.25 | 0.86 | 68.2 | 1.26 |

| HDXMb | 0.80 | 28.2 | 0.49 | 0.79 | 27.3 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 37.2 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 52.0 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 62.6 | 1.06 |

| C4g-C4fc | 36.2 | 34.6 | 52.9 | 71.3 | 73.9 | ||||||||||

averaged values from the CH vectors in the two sugar rings (first 8 rows).

averaged values from the CH vectors from hydroxymethyl groups (last 3 rows).

the overall rotation constant, τm, is computed from the single exponential fitting for the correlation function of the vector (C4g-C4f) crossing two rings (with errors < 1%).

We fit the correlation function for a given atom pair to double-exponential or triple-exponential function using a perl script invoking the fit routine in Gnuplot which minimizes the residual error using the nonlinear least squares Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm. The typical fitting range varies for different systems: 0 to 500 ps for sucrose in pure water and low concentrations, 0 to 5 ns for sucrose in water-DMSO mixture and high concentrations. Adjusting the fitting ranges did not induce obvious changes to the fitting parameters since we have obtained the trajectories a couple of orders longer than the characteristic time constants of overall rotations. For the sucrose studied two-exponential fittings from Gnuplot usually resulted in smaller variances of fitting parameters (less than 5% in general) than triple-exponential form except for systems at high concentrations of sucrose or water-DMSO mixture. In this report, all correlation functions are fit to a double-exponential form as in the model free formalism,27

| (16) |

where τm and τe define characteristic times of the exponential decays, and , and S2 is a measure of the amplitude of internal motion.

When a molecule is small the overall rotational constant τm is also small. If τm≫τe and are satisfied, one has the extreme narrowing regime35

| (17) |

From equations 10 and 11 it is easy to see that R1 ≈ R2 ∞ τm, and nothing can be learned about internal motions from such data. It is for this reason that low temperatures or viscous solvents are used for relaxation studies on small molecules like sucrose.

3. Results and Discussion

1. Simulations of sucrose in pure water at varying sucrose concentrations

1. Free Energy Landscapes

In Figure 1, we show the free energy landscapes in φ – ψ glycosidic space for sucrose in TIP4P/Ew waters at different concentrations, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 mol/L. The free energy surfaces were constructed via the Equation 1 from the probability distributions averaged over all sucrose molecules in solution. As in our previous study,47 we found four major minima, shown in Table 1. There is no significant concentration effect compared to simulations of one sucrose molecule case found earlier.47 The global minimum M1 is also close to the crystal conformation (108°,305°).74 All F1s are global minima and the free energy differences between F1 and F2 are small. The probabilities (P1) of the sucrose molecule staying around the global minima (M1) are close to that of M2. Namely, there two conformations are almost equally important. Our analysis47 of experimental RDC and J-coupling data suggested that M2 should be much less populated than is found with the force fields used here.

Figure 1.

Free energy landscapes in φ – ψ glycosidic space for sucrose in TIP4P/Ew waters at T = 298 K and different concentrations. The contour lines were generated from 0.0 to 5.0 kcal/mol by the difference of 0.1.

Table 1.

Free energy information of four minima of sucrose in TIP4P/Ew waters at different concentrations with T = 298 K. Positions give (φ, ψ) value in degrees; energies of the minima barriers between minima are in kcal/mol; populations integrate the Boltzmann populations in a circle of radius 20° about the minimum.

| 0.1 mol/L | 0.5 mol/L | 1.0 mol/L | 2.0 mol/L | 3.0 mol/L | 4.0 mol/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| positions | ||||||

| M1 | (101.4, 302.5) | (104.3, 302.6) | (101.6, 301.83) | (102.0, 301.9) | (103.7, 303.9) | (102.1, 302.2) |

| M2 | (71.0, 286.9) | (71.5, 288.8) | (71.7, 287.9) | (73.4, 288.7) | (72.4, 288.6) | (74.1, 289.0) |

| M3 | (83.9, 193.7) | (85.1, 194.3) | (83.8, 194.9) | (82.9, 193.3) | (84.1, 194.9) | (85.1, 195.4) |

| M4 | (91.1, 51.3) | (89.9, 55.1) | (90.3, 55.4) | (87.2, 55.1) | (89.8, 55.4) | (92.2, 55.2) |

| energies | ||||||

| F1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| F2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| F3 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| F4 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| populations | ||||||

| P1 | 0.472 | 0.456 | 0.478 | 0.504 | 0.522 | 0.502 |

| P2 | 0.444 | 0.481 | 0.475 | 0.444 | 0.429 | 0.399 |

| P3 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.01 | 0.024 |

| P4 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.008 |

| barriers | ||||||

| B12 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| B23 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| B14 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

2. Relaxation Parameters

Early NMR studies14–17,23,35 on sucrose in solution usually resorted to the measurement of relaxation parameters R1 and R2. For direct comparison we calculated these values from the MD simulation trajectories. Figure 2 displays the reorientation correlation functions for a typical vector (C-H1g) of the glucose ring in sucrose for different water models and concentrations of sucrose. All curves decay smoothly to zero as the time is increased. In Figure 2(c), as an example, we also show the model-free expression for the correlation function at 0.1 mol/L and T = 298K. The calculated data is fitted very well with small uncertainties in the resulting parameters.

Figure 2.

Reorientation correlation functions of C-H1g vector of glucose residue in sucrose. In (c), the fitting curve of model-free formula is also shown with S2 = 0.84±0.01, τm = 74.76±0.45 and τ = 9.56±0.65

Table 2 lists the R1 and R2 values of sucrose in various explicit water models: SPC/E,63 TIP3P,64 TIP4P,65 TIP4P/Ew,66 and TIP5P.68 There is an obvious model dependence, even though the free energy surfaces are very similar.47 R1 and R2 for TIP4P/Ew and TIP5P have largest values, and are almost twice those of TIP3P. This effect of water models is due to the fact that the rotational diffusion of sucrose depends on the water model.75,36 For example the self diffusion coefficients of SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP4P/Ew and TIP5P at T = 298 K are 3.85, 5.19, 3.29, 2.4 and 2.62 (×10−5 cm2/s) respectively, and all these values are larger than the experimental value of 2.30.75 This is probably the main reason for the wide distribution of rotational time constants (τm in Table 2) for different water models, ranging from 30 to 70 ps. From Table 2, it is apparent that TIP4P/Ew and TIP5P have the slowest dynamics among the studied water models. These trends closely resemble those reported earlier for peptides and proteins.24,36 Furthermore, the simulations are carried out in H2O whereas the experiments used nearly pure D2O. There is no rigorous way to “correct” the simulations, since both the mass of the hydrogen and the importance of nuclear quantum effects lead to differences between light and heavy water. As a simple approximation, one can scale τm (and R1 in the extreme narrowing limit) by 1.23, which is the ratio of the viscosities of heavy and light water. But this is only a rough correction, and this plus the strong dependence of the computed results on water model suggest that the main error in the calculations (at least for these sorts of relaxation properties) lies in the values of molecular tumbling times, although errors in the populations of different internal conformers might also play a role.

In addition to determining a τm value for each CH vector, we also calculated the average τm for the 8 CH vectors in two sugar rings as shown in Table 2. We also directly computed the overall tumbling from the single exponential fitting for the correlation function of the vector (C4g-C4f) crossing two rings. All values agree well with each other and are close to the values from each CH vector in the rings. Hence, (nearly) isotropic rotation of an approximately rigid molecule seems to be a good approximation. The observed relaxation rates for carbons bonded to a single hydrogen23 have only a small scatter, and the details of their relative values change are a strong function of concentration (see Fig. 4 of Ref. 23), suggesting that attempts to interpret molecular shape from an anisotropic tumbling model is probably beyond the expected accuracy of the current results.

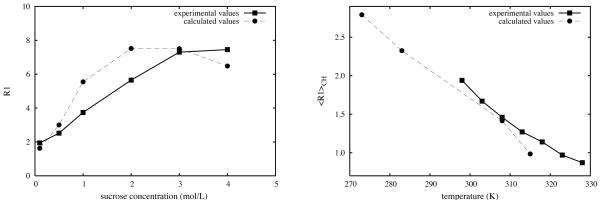

Figure 3 shows R1 at different concentrations.23 For a direct comparison, R1 has been averaged over all the C atoms from the two sugar rings and three hydroxymethyl groups as in the experimental analysis.23 Generally the calculated values are in good agreement with experiment, although the difference becomes larger as the concentration is increased.

Figure 3.

R1 values of sucrose in TIP4P/Ew water at B=5.875 T (left) at T=298K as a function of sucrose concentration, and (right) at low concentration (0.02M calc., 0.1M exp) as a function of temperature. R1 values have been averaged over all the C atoms in the two sugar rings and three hydroxymethyl groups. Experimental values are from Reference.23 Calculated R1 values have been multiplied by 1.23, to approximately account of the greater viscosity of D2O vs H2O.

In contrast, there is little dependence on water model for the generalized order parameters. We found that the S2 values of C atoms in the glucose ring (C-H1g, C-H2g, C-H3g, C-H4g, and C-H5g) are close to 0.90 which is consistent with the assumption that the glucose residue is rather rigid. The relatively larger variations and slightly smaller values of S2 from C-H3f, C-H4f, and C-H5f in the fructose ring indicate that this ring has larger fluctuations than the glucose ring. The order parameters from hydroxymethyl carbon-13 nuclei (C-H6g, C-H1f, and C-H6f) are in turn smaller than those of atoms in the rings, which originates from the larger degree of mobility of hydroxymethyl groups.17 These simulation results are consistent with the experimental data where averaged S2 are 0.92 for ring atoms and 0.77 for hydroxymethyl carbons at T=273K.17 We also notice that the S2 values from both ring atoms are still large >0.80 although significant transitions exist between M1 and M2 as shown in Figure 1S. The transition times from M1 to M2 are about 50 ps at T = 300K, which are close to overall rotational time constants (τm in Table 2). Hence the transitions between M1 and M2 are internal motions have the time scale close to that of overall rotation motions and will not greatly affect S2. But this also means that errors in our estimated populations of free-energy minima will not be evident in this sort of analysis.

The temperature effects on relaxation data are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 3, showing that τm and relaxation rates increase significantly as the temperature is lowered. The average τm values (around 50 ps at 315 K) are somewhat smaller than experimental values at low concentrations (70 ps in 0.5M solution at 315K35 and 50 ps in 0.1M solution at 328K23). As might be expected, values of S2 increase slightly at lower temperature.

Table 3.

Calculated relaxation parameters in TIP4P/Ew water at B = 9.4 T. R1, R2 in s−1, τm in ps.)

| 273K | 283K | 300K | 315K | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-H | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 | S2 | τm | R1 |

| C-H1g | 0.93 | 118 | 2.28 | 0.92 | 105 | 2.03 | 0.90 | 63 | 1.22 | 0.79 | 48 | 0.86 |

| C-H2g | 0.93 | 125 | 2.42 | 0.89 | 113 | 2.11 | 0.91 | 66 | 1.28 | 0.89 | 46 | 0.88 |

| C-H3g | 0.92 | 125 | 2.39 | 0.86 | 115 | 2.10 | 0.90 | 65 | 1.26 | 0.89 | 45 | 0.86 |

| C-H4g | 0.91 | 133 | 2.51 | 0.89 | 112 | 2.11 | 0.89 | 69 | 1.31 | 0.88 | 47 | 0.90 |

| C-H5g | 0.93 | 127 | 2.44 | 0.90 | 112 | 2.11 | 0.90 | 67 | 1.30 | 0.89 | 46 | 0.89 |

| C-H3f | 0.82 | 153 | 2.65 | 0.90 | 105 | 2.00 | 0.85 | 68 | 1.25 | 0.86 | 47 | 0.87 |

| C-H4f | 0.84 | 136 | 2.38 | 0.84 | 107 | 1.91 | 0.86 | 58 | 1.08 | 0.82 | 44 | 0.79 |

| C-H5f | 0.87 | 150 | 2.68 | 0.87 | 118 | 2.14 | 0.88 | 69 | 1.30 | 0.86 | 50 | 0.92 |

| C-H6g | 0.81 | 111 | 1.90 | 0.81 | 94 | 1.61 | 0.77 | 58 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 37 | 0.62 |

| C-H1f | 0.83 | 99 | 1.75 | 0.83 | 83 | 1.47 | 0.84 | 51 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 36 | 0.63 |

| C-H6f | 0.79 | 92 | 1.53 | 0.75 | 77 | 1.25 | 0.75 | 46 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 34 | 0.54 |

Table 2S shows the relaxation data for Carbon-13 nuclei in sucrose calculated from MD simulations at different concentrations. At low concentrations (0.1M and 0.5M), R1 is almost equal to R2 as the case of without sucrose-sucrose interactions in Table 2. As the concentration is increased, R1, R2 and the ratio R2/R1 becomes larger as we leave the extreme narrowing regime. The increase of R1 and R2 values stems from the slower decay of reorientation correlation function as shown by the large values of τm. In Table 2S, we list all other calculated relaxation data from the fitting as model-free formula in Equation 16. We also fit the data with the three-exponential form. The resulting R1/R2 values (Table 3S), however, show no pronounced changes.

2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations with a water-DMSO Mixture

1. Free Energy Landscapes

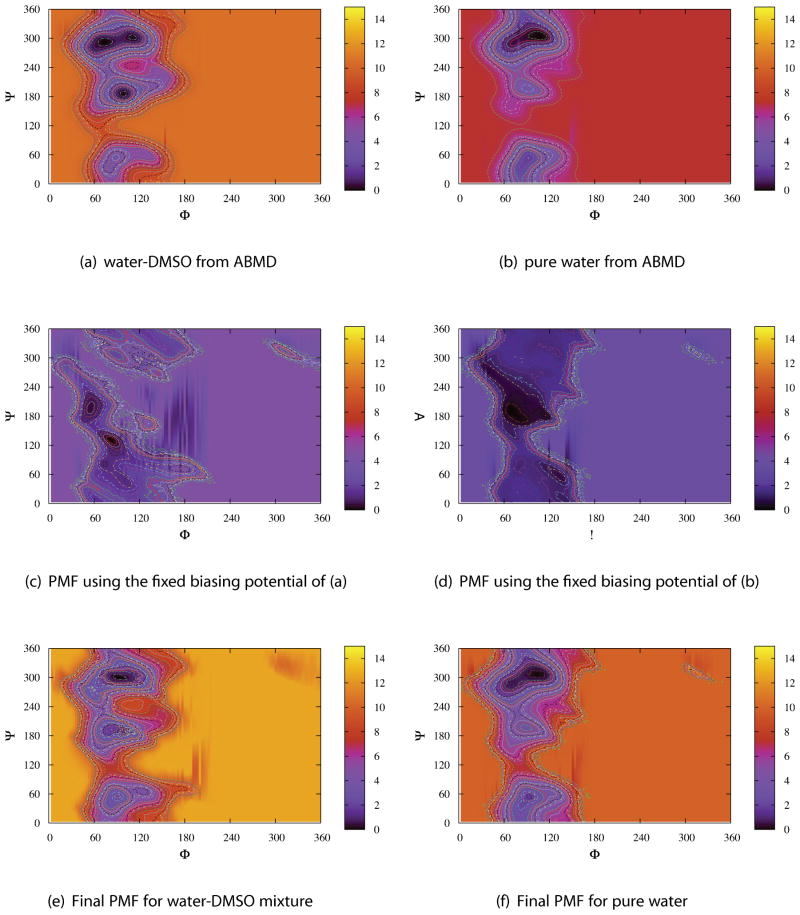

Figure 4 shows the free energy landscapes in φ – ψ glycosidic space in pure water and 7:3 water-DMSO mixture at two different temperatures T = 273 and 283 K. These free energy surfaces were constructed by Equation 1 from 100ns normal MD simulations with the initial crystal conformation of sucrose. It is evident that during the 100ns simulations the sucrose molecule in water-DMSO mixture is trapped in the minimum M1 or M2 and only a local equilibrium state was approached. Hence the PMFs in Figure 4(c) and (d) are not converged as transitions to M3 and M4 could not be observed within 100 ns as in pure water. This implies that the free energy barriers between M1 and M4 or M2 and M3 could be higher than that in pure water at the same temperature. To overcome these high barriers and obtain more information in other high-energy regions, we performed ABMD simulations both in pure water and water-DMSO mixture. Figures 2S and 3S show the free energy surface (the negative value of biasing potential) at different times of ABMD flooding simulation. The probabilities within the circle region of 20°of all four minima are plotted in Figure 4S as a function of flooding time. The biasing potential roughly converges at 12 ns for pure water and 40 ns for water-DMSO mixture. Following the ABMD flooding simulations we performed 100 ns simulations with the fixed biasing potential from the ABMD procedure. The resulting surfaces are displayed in Figures 5 and 6 for T = 273 K and 283 K respectively. A large portion of φ – ψ space is sterically disallowed due to the overlap of atoms from two sugar rings.76 These free energy maps cover most of the sterically allowed regions for the disaccharide, but most of the conformations are in the M1 or M2 regions.

Figure 4.

The free energy landscapes in φ – ψ glycosidic space for sucrose in pure water and water-DMSO mixture at different temperatures from 100ns normal MD simulations. Note that in (c) and (d) the systems only visit a portion of PMFs as constructed from ABMD simulations in Figures 5 and 6, so the PMFs shown here are not converged.

Figure 5.

The free energy landscapes in φ – ψ glycosidic space for sucrose in the water-DMSO mixture and the TIP4P/Ew pure water at T = 273 K from ABMD simulations. The contour lines were generated from 0.0 to 10.0 kcal/mol in steps of 0.25.

Figure 6.

The free energy landscapes in φ – ψ glycosidic space for sucrose in the water-DMSO mixture and the TIP4P/Ew pure water at T = 283 K from ABMD simulations. The contour lines were generated from 0.0 to 10.0 kcal/mol in steps of 0.25.

From the final free energy maps in Figures 5 and 6, we collected important information pertaining to the free energy minima as listed in Table 4. Although the four minima found pure water are also present in water-DMSO mixture, there are significant differences in their relative energies. The global minimum is dependent on temperature. Namely, M1 is the global minimum at 283 K but M2 at 273 K. The positions of minima are also shifted slightly. The free energy barriers B23 (from M2 to M3) and B14 (from M1 to M4) are much higher (at least 2–3 KCal/mol) than that in pure water. These changes on potential of mean force have resulted in the significant probability differences between M1 and M2 as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Free energy information of four minima of sucrose in pure water and water-DMSO mixture at two different temperatures from the ABMD simulations.

| Water | Water-DMSO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = 273 K | T = 283 K | T = 300 K | T = 273 K | T = 283 K | |

| positions (φ, ψ) (in degree) | |||||

| M1 | (107.9, 305.7) | (104.5, 306.1) | (104.8, 305.4) | (108.8, 308.5) | (97.7, 302.8) |

| M2 | (72.9,286.6) | (69.7, 283.3) | (69.9, 284.7) | (70.8, 298.6) | (67.2, 286.2) |

| M3 | (85.2, 198.4) | (88.5, 195.9) | (83.3, 196.4) | (96.2, 199.2) | (83.8, 193.3) |

| M4 | (92.2, 51.5) | (92.9, 54.3) | (94.8, 54.9) | (80.5, 54.3) | (89.7, 55.6) |

| heights (in kcal/mol) | |||||

| F1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| F2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 2.1 |

| F3 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 1.8 |

| F4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| probabilities within a radius of 20 degree | |||||

| P1 | 0.458 | 0.557 | 0.577 | 0.055 | 0.748 |

| P2 | 0.351 | 0.241 | 0.355 | 0.889 | 0.089 |

| P3 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.061 |

| P4 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.024 | 0.012 | 0.015 |

| barriers between minima (in KCal/mol) | |||||

| B12 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| B23 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 7.2 | 2.4 |

| B14 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

2. Relaxation Parameters

We chose our temperature and DMSO content to match experimental conditions reported by Effemey and Kowalewski.17 We also calculated the R1 and R2 values for 11 Carbon-13 nuclei from the 100 ns trajectories with normal MD simulations at both temperatures. The resulting values along with corresponding experimental data17 are listed in Table 5 and plotted in Figure 7. Calculated values of R1 agree well with experiment. In contrast, the values of R2 are generally overestimated although the numbers are reasonable. This is mostly due to the fact that the global rotational time is slightly longer in the simulations (τm ≈ 2 ns at T = 273 K) than experiments17 (τm ≈ 1.5 ns from the ring atoms at T = 273 K). Note that this is opposite to the behavior seen in pure water, where values of τm extracted from the simulation were smaller than those extracted from experiment.

Table 5.

Calculated relaxation data for the Carbon-13 nuclei of sucrose in 7:3 water-DMSO mixture at different temperatures and B = 9.4T. The averaged S2 for ring atoms from experimental model-free fitting in Ref.47 are 0.92 and 0.86 for T= 273 and 283 K respectively. Experimental values from Ref. 17 with S2 values derived from model-free fits. R1, R2 values in s−1, τm in ps.

| 273K | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp. | calc. | ||||||||

| C-H | S2 | R1 | R2 | NOE | S2 | τm | R1 | R2 | NOE |

| C-H1g | 5.48 | 9.5 | 1.27 | 0.89 | 2006 | 5.30 | 10.81 | 1.25 | |

| C-H2g | 5.32 | 8.5 | 1.27 | 0.87 | 2003 | 5.24 | 10.64 | 1.26 | |

| C-H3g | 0.89 | 2153 | 5.17 | 11.28 | 1.24 | ||||

| C-H4g | 0.92 | 5.32 | 8.4 | 1.30 | 0.88 | 2776 | 4.64 | 13.25 | 1.26 |

| C-H5g | 0.87 | 1939 | 5.30 | 10.44 | 1.27 | ||||

| C-H3f | 5.17 | 8.6 | 1.32 | 0.90 | 2296 | 5.06 | 11.82 | 1.23 | |

| C-H4f | 5.39 | 8.9 | 1.30 | 0.87 | 2143 | 5.07 | 11.02 | 1.24 | |

| C-H5f | 5.18 | 9.6 | 1.30 | 0.87 | 2450 | 4.81 | 12.02 | 1.24 | |

| C-H6g | 0.78 | 4.63 | 6.9 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 706 | 4.25 | 5.08 | 1.70 |

| C-H1f | 0.80 | 4.56 | 7.7 | 1.34 | 0.63 | 1230 | 4.60 | 6.42 | 1.55 |

| C-H6f | 0.74 | 4.37 | 6.8 | 1.45 | 0.75 | 1869 | 4.84 | 9.03 | 1.35 |

| 283K | |||||||||

| exp. | calc. | ||||||||

| C-H | S2 | R1 | R2 | NOE | S2 | τm | R1 | R2 | NOE |

| C-H1g | 5.23 | 7.2 | 1.54 | 0.77 | 1454 | 5.63 | 8.58 | 1.49 | |

| C-H2g | 4.91 | 6.9 | 1.53 | 0.81 | 1585 | 5.55 | 9.05 | 1.42 | |

| C-H3g | 0.85 | 1398 | 5.56 | 8.56 | 1.37 | ||||

| C-H4g | 0.86 | 4.82 | 6.9 | 1.58 | 0.82 | 1657 | 5.43 | 9.21 | 1.38 |

| C-H5g | 0.82 | 1602 | 5.54 | 9.15 | 1.40 | ||||

| C-H3f | 4.99 | 7.2 | 1.41 | 0.70 | 2014 | 5.19 | 9.59 | 1.52 | |

| C-H4f | 4.99 | 7.0 | 1.56 | 0.68 | 1607 | 5.21 | 8.23 | 1.56 | |

| C-H5f | 5.21 | 7.4 | 1.44 | 0.68 | 2083 | 5.08 | 9.56 | 1.55 | |

| C-H6g | 0.81 | 4.23 | 5.6 | 1.62 | 0.77 | 970 | 4.93 | 6.44 | 1.49 |

| C-H1f | 0.75 | 4.41 | 5.3 | 1.63 | 0.65 | 725 | 4.38 | 5.19 | 1.79 |

| C-H6f | 0.71 | 3.95 | 4.8 | 1.77 | 0.62 | 685 | 3.94 | 4.65 | 1.79 |

Figure 7.

Relaxation data for Carbon-13 nuclei in sucrose with 7:3 water-DMSO mixture at different temperatures and B = 9.4 T. Experimental data are from Reference.17

The Lipari-Szabo order parameters S2 (≈ 0.9 at T = 273 K) for the ring carbons as listed in Table 5 are slightly smaller that experimental values17 (The averaged S2 value for ring carbons from experimental model-free fitting 17 is 0.92 although no values were shown for individual atoms). There are no significant differences between ring carbons from glucose and that from fructose. This is opposite to the results for pure water listed in Table 2, where the S2 values in the fructose ring are up to 10% smaller than in glucose. This difference might be understood by the probability density distribution of pucker phase angles of fructose ring as shown in Figure 5S. The distribution from pure water has wider spread than that from water-DMSO mixture, i.e., the fructose ring is more flexible in pure water than in the mixed solvent. From Table 5 we also can find that the calculated values of S2 for three hydroxymethyl carbons are slightly smaller than their corresponding values in experiments.17 Hydrogen-bond analysis shows sucrose at DMSO mixture has larger occupations (25.54% of O2g-H1Of and 15.08% of O5g-H6Of at T = 283K, 0.0% of O2g-H1Of and 83.31% of O5g-H6Of at T = 273K) comparing to that of pure water as shown in the previous paper47(10.51% of O2g-H1Of and 5.86% of O5g-H6Of at T = 283K, 8.18% of O2g-H1Of and 5.45% of O5g-H6Of at T = 273K). The stronger hydrogen-bond connections are consistent with the larger S2 values and higher free energy barriers in DMSO mixture as discussed above.

4. Conclusions

Continuing our earlier simulations47, we performed MD simulations of sucrose to reproduce NMR experimental conditions such as temperature (273 to 315 K), concentration of sucrose (0.1M to 4.0M), and solvent type (pure water and water-DMSO mixture). To avoid the problem of high-free energy barriers in the water-DMSO mixture, we also carried out adaptively biased MD simulations. NMR relaxation parameters such as 13 C spin-lattice and spin-spin relaxation rates were directly calculated from the simulations; given the capabilities of modern computers, such comparisons are increasingly straightforward to carry out. Generally the R1 and R2 values are slightly underestimated in pure water and overestimated in water-DMSO mixture due to faster or slower rotational dynamics. Nevertheless, the errors found here are generally smaller than those found in similar calculations on proteins.

The calculations suggest that the structure and internal dynamics of sucrose in water is not much affected by the sucrose concentration, although the overall viscosity of the solution (as monitored by molecular tumbling times) increases with concentration (and with decreasing temperature) is a way that closely matches experiment. However, the differences between water and DMSO-water are not large, and it is not clear how much credence should be given to such changes, given the uncertainties in the water and DMSO force field models used here.

The calculated order parameters S2 from ring atoms are large (>0.85) both in pure water and water-DMSO mixture. The S2 values from fructose ring atoms in pure water general are smaller than that of glucose. In contrast, no such difference is observed for sucrose in the water-DMSO mixture. This indicates that although the crystal conformation still dominates, sucrose might have more conformational flexibility in pure water than in the mixture. This result is consistent with the narrower distribution of pucker phase angles of the fructose ring, the larger occupations of inter-residue hydrogen bonds, and the higher free energy barriers to other metastable states in DMSO/water versus water. Hence the rigidity of sucrose molecule seems to be sensitive to the solvent environment. The order parameters S2 are also significantly larger than experimental data from other sugars such as heparin sulfate NA-domains (0.30~0.70),28 hyaluronan oligosaccharides (0.30~0.65),32 human milk oligosaccharide(0.30~0.80).8 This implies that considerable internal motions might exist for these sugars. We expect that the same procedure can be applied for understand the conformation flexibility of these complex sugars.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant GM45811. We thank Dr. Andreas Dolle for kindly providing R1 data, and Volodymyr Babin and Celeste Sagui for useful discussions about adaptively-biased simulations.

References

- 1.Cumming DA, Carver JP. Biochemistry. 1987;26:6664–6676. doi: 10.1021/bi00395a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imberty A, Perez S. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4567–4588. doi: 10.1021/cr990343j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMarco ML, Woods RJ. Glycobiology. 2008;18:426–440. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Pastor M, Bush CA. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8045–8055. doi: 10.1021/bi9904205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-Pastor M, Bush CA. Carbohydr Res. 2000;323:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(99)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venable RM, Delaglio F, Norris SE, Freedberg DI. Carbohydr Res. 2005;340:863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poppe L, Vanhalbeek H. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1092–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rundlof T, Venable RM, Pastor RW, Kowalewski J, Widmalm G. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11847–11854. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Case DA. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:325–331. doi: 10.1021/ar010020l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daragan VA, Mayo KH. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1997;31:63–105. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Case DA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prestegard JH, Bougault CM, Kishore AI. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3519–3540. doi: 10.1021/cr030419i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bock K, Lemieux RU. Carbohydr Res. 1982;100:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCain DC, Markley JL. Carbohydr Res. 1986;152:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCain DC, Markley JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:4259–4264. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs H, Bagley S, Kowalewski J. J Magn Reson. 1989;85:530–541. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Effemey M, Lang J, Kowalewski J. Magn Reson Chem. 2000;38:1012–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neubauer H, Meiler J, Peti W, Griesinger C. Helv Chim Acta. 2001;84:243–258. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupenhoat CH, Imberty A, Roques N, Michon V, Mentech J, Descotes G, Perez S. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3720–3727. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams B, Lerner L. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4827–4829. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duker JM, Serianni AS. Carbohydr Res. 1993;249:281–303. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84096-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batta G, Kover KE. Carbohydr Res. 1999;320:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baraguey C, Mertens D, Dolle A. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:6331–6337. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawzi NL, Phillips AH, Ruscio JZ, Doucleff M, Wemmer DE, Head-Gordon T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6145–6158. doi: 10.1021/ja710366c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer AG, Rance M, Wright PE. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4371–4380. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clore GM, Szabo A, Bax A, Kay LE, Driscoll PC, Gronenborn AM. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4989–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipari G, Szabo A. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mobli M, Nilsson M, Almond A. Glycoconjugate J. 2008;25:401–414. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almond A, DeAngelis PL, Blundell CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1086–1087. doi: 10.1021/ja043526i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eklund R, Lycknert K, Soderman P, Widmalm G. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:19936–19945. doi: 10.1021/jp053198o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angulo J, Hricovini M, Gairi M, Guerrini M, de Paz JL, Ojeda R, Martin-Lomas M, Nieto PM. Glycobiology. 2005;15:1008–1015. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lycknert K, Widmalm G. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1015–1020. doi: 10.1021/bm0345108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson TJ, Venable RM, Egan W. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2930–2939. doi: 10.1021/ja0210087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poveda Ana, Asensio Juan Luis, Martin-Pastor Manuel, Jimenez-Barbero Jesus. J Biomol NMR. 1997;10:29–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1018395627017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allerhand A, Doddrell D, Komoroski R. J Chem Phys. 1971;55:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong V, Case DA. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:6013–6024. doi: 10.1021/jp0761564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peter C, Daura X, van Gunsteren WF. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:297–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1011241030461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong V, Case DA, Szabo A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11016–11021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809994106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tran VH, Brady JW. Biopolymers. 1990;29:961–976. doi: 10.1002/bip.360290609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran VH, Brady JW. Biopolymers. 1990;29:977–997. doi: 10.1002/bip.360290610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engelsen SB, Dupenhoat CH, Perez S. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:13334–13351. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engelsen SB, Perez S. Carbohydr Res. 1996;292:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engelsen SB, Monteiro C, de Penhoat CH, Perez S. Biophys Chem. 2001;93:103–127. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casset F, Imberty A, duPenhoat CH, Koca J, Perez S. J Mol Struc-Theochem. 1997;395:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 45.French AD, Kelterer AM, Cramer CJ, Johnson GP, Dowd MK. Carbohydr Res. 2000;326:305–322. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.French AD, Kelterer AM, Johnson GP, Dowd MK, Cramer CJ. J Comput Chem. 2001;22:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia Junchao, Case David A. Sucrose in Aqueous Solution Revisited: 1. Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Direct and Indirect Dipolar Coupling Analysis. 2011 doi: 10.1002/bip.22017. Submitted for Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.French AD, Brady JW, editors. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 430 American Chemical Society; Washington, D C: 1990. Computer Modelling of Carbohydrate Molecules. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vliegenthart JFG, Woods RJ, editors. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 930 American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2006. NMR Spectroscopy and Computer Modeling of Carbohydrates: Recent Advances. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dwek RA. Chem Rev. 1996;96:683–720. doi: 10.1021/cr940283b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia JC, Margulis CJ. J Biomol NMR. 2008;42:241–256. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xia JC, Daly RP, Chuang FC, Parker L, Jensen JH, Margulis CJ. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:1620–1628. doi: 10.1021/ct700033y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xia JC, Daly RP, Chuang FC, Parker L, Jensen JH, Margulis CJ. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:1629–1643. doi: 10.1021/ct700034q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xia JC, Margulis CJ. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:3081–3088. doi: 10.1021/bm900756q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voter AF. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;78:3908–3911. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grubmuller H. Phys Rev E. 1995;52:2893–2906. doi: 10.1103/physreve.52.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamelberg D, Mongan J, McCammon JA. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:11919–11929. doi: 10.1063/1.1755656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laio A, Parrinello M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12562–12566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Darve E, Pohorille A. J Chem Phys. 2001;115:9169–9183. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Babin V, Roland C, Sagui C. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:134101–134107. doi: 10.1063/1.2844595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kirschner KN, Yongye AB, Tschampel SM, Gonzalez-Outeirino J, Daniels CR, Foley BL, Woods RJ. J Comput Chem. 2008;29:622–655. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berendsen HJC, Grigera JR, Straatsma TP. J Phys Chem. 1987;91:6269–6271. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jorgensen WL, Madura JD. Mol Phys. 1985;56:1381–1392. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horn HW, Swope WC, Pitera JW, Madura JD, Dick TJ, Hura GL, Head-Gordon T. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:9665–9678. doi: 10.1063/1.1683075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tschampel SM, Kennerty MR, Woods RJ. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:1721–1733. doi: 10.1021/ct700046j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahoney MW, Jorgensen WL. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:8910–8922. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martinez JM, Martinez L. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:819–825. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chalaris M, Marinakis S, Dellis D. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2008;267:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fox T, Kollman PA. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:8070–8079. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Case DA. J Biomol NMR. 1999;15:95–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1008349812613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sherwood DW, Grant DM. J Magn Reson A. 1993;104:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown GM, Levy HA. Acta Crystallogr Sect B. 1973;29:790–797. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guillot B. J Mol Liq. 2002;101:219–260. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rao VSR, Qasba PK, Balaji PV, Chandrasekaran R. Conformation of Carbohydrates. Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.