Abstract

The normative influence of parents, close friends, and other peers on teens’ sexual behavior has been well documented. Yet, we still know little about the processes through which these oftentimes competing norms impact teens’ own sexual norms and behaviors. Drawing on qualitative data from 47 interviews conducted with college-bound teens, we investigate the processes through which perceived parental, close friend, and other peer norms about sex influenced teens’ decisions about whether and when to have sex. Although virtually all teens perceived that most of their peers were having sex and that parents were almost universally against teen sex, some teens had sex and others did not. Our findings demonstrate that teens who remained virgins and those who were sexually active during high school often negotiated different sets of competing norms. Differences in understandings of age norms, in close friends’ sexual norms and behaviors, and in communication about sex with parents, close friends and other peers were related to different levels of sexual behavior for teens who otherwise shared many similarities in social location (e.g.. class, race, and educational status). While virgins reported an individualized process of deciding whether they were ready for sex, we find that their behavior fits within a traditional understanding of an age norm because of the emphasis on avoiding negative sanctions. Sexually experienced teens, on the other hand, explicitly reported abiding by a group age norm that prescribed sex as normal during high school. Finally, parents’ normative objections to teen sex – either moral or practical – and the ways they communicated with their teen about sex had important influence on teens’ own sexual norms and behaviors during high school.

Keywords: Age norms, sexual behavior, teenage sex, adolescence, communication, parental and peer influences

1. Introduction

In the United States and many other developed countries, most young people today will have sex before they finish high school (Darroch, Singh, Frost, & Team, 2001; Regnerus, 2007; Risman & Schwartz, 2002). Sexual transitions are important events in teens’ lives that may lead to positive outcomes, such as identity development and emotional autonomy from parents (Dowdy & Kliewer, 1998); or negative outcomes, such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or unintended pregnancies in the absence of contraception. Adolescence is, therefore, a crucial time for teens to have accurate information about sex. Most teens report that they would prefer to communicate about sex with their parents (Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998; Whitaker & Miller, 2000), yet many feel they do not get enough information (Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1994). Previous research has found no clear relationship between parental norms and communication about sex and teen sexual behavior (Whitaker and Miller 2000). However, we know that teen sexual behavior is strongly imbedded in peer social networks (Vacirca, Ortega, Rabaglietti, & Ciairano, 2011) and influenced by peers’ behaviors (Kinsman, Furstenberg, & Schwarz, 1998; Sieving, Eisenberg, Pettingell, & Skay, 2006). Some scholars have argued that teen sexual behavior is jointly influenced by parents and peers (Jaccard & Dittus, 1993; Whitaker & Miller, 2000), but few studies have analyzed the influence of these often competing reference groups. Therefore, to better understand the multiple influences on teen sexual norms and behaviors, we focus on parents’, close friends’, and other peers’ communication and norms about sex during high school.

Prior research has demonstrated a strong relationship between teens’ perceptions of family and peer norms about the appropriateness of teen sex and their own sexual behavior (see Kirby, 2001a for a review). Yet, we still know little about the ways in which socio-demographic and family factors are translated into micro-level processes, such as decision-making about sex (Gillmore et al., 2002). Furthermore, social influences, especially peer norms, are important determinants of teens’ sexual behavior, yet the processes through which norms influence behavioral change are not well understood (Kinsman, et al., 1998; Sieving, et al., 2006). Analyzing 47 qualitative interviews with college-bound teens, we draw on the life course theoretical perspective to highlight teens’ subjective understandings and internalizations of the appropriate timing of sex and the ways these understandings are influenced by parents, close friends, and other peers through communication and sanctioning. In this way, we respond to the call from Elliott (2010, p. 208) for research investigating “how youth interpret their parents’ lessons about sexuality and the meanings young people give to sexuality.”

Studying college-bound teens is valuable as we can be reasonably sure that for these teens, in particular, sex has at least some potential consequences that they would want to avoid given their college plans. It is likely that higher socioeconomic status (SES) teens are encouraged by parents, teachers, and peers to postpone family formation until they have completed their education and begun their careers, an expectation defined by Hamilton and Armstrong (2009) as the self-development imperative. However, these college-bound youth have also inherited the culture of “hooking up” that characterizes a more casual attitude toward teen sexual behavior on many college campuses today (Armstrong, Hamilton, & England, 2010; England, Shafer, & Fogarty, 2008; Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009). Understanding the ways that college-bound teens actually understand and respond to sexual norms during high school can provide some insight into the ways that such competing norms influence (or fail to influence) sexual attitudes and behaviors.

We did not set out to compare teens who were virgins throughout high school with those who were sexually active; rather, this distinction emerged inductively as fundamental for understanding norms and communication about teen sex.1 Even though both sets of teens perceived that most of their peers had sex before leaving high school and virtually all of their parents disapproved of teen sexual activity, some teens became sexually active and others did not. Teens with different levels of sexual experience understood the appropriate timing of sex in different ways based on the content and type of social norms they were subjected to and perceived as important. In essence, despite similar contexts and social locations, these college-bound virgins and sexually experienced teens negotiated and drew on different sets of norms from parents, close friends, and other peers in deciding whether or not to have sex during high school.

2. Background

2.1 Teen Sexual Behavior in U.S. Context

This project draws on data collected in the United States, a context in which many adults are uncomfortable with the idea of teenagers having sex (Fields, 2008; Schalet, 2004, 2010). A highly visible consequence of teen sex, teen parenting, has been viewed as a major social problem in the U.S. for decades. There are many aspects of the U.S. cultural landscape that set it apart from other developed countries with respect to teen sex and pregnancy. For instance, American teens’ contraceptive use lags compared to peers in other developed countries (Darroch, et al., 2001), and in many areas of the United States, reproductive health services and contraceptives are not readily available to women (Jones, Zolna, Henshaw, & Finer, 2008). These circumstances have contributed to the U.S. having one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy and birth in the fully industrialized world (Perper & Manlove, 2009), although teen childbearing is more prevalent among lower-SES subpopulations (Holcombe, Peterson, & Manlove, 2009) and teens who identify as African American, Latina, or Native American (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2009).

Scholars have noted other differences between the United States and other developed countries. For example, in a study of Dutch and American teen girls’ sexual subjectivities, Schalet (2010) found notable differences in girls’ sexual agency and pleasure: American teen girls’ sexual relationships were much more likely to be contested by parents such that these teens were essentially forced to differentiate between their roles as “good daughters” and “sexual actors” (p. 325). Schalet argues that these cross-cultural differences are related to variations in parental beliefs about whether teen girls are capable of engaging in the types of relationships that legitimate heterosexual sex. The level of parental disapproval of teen sex in Schalet’s study reflects the overall cultural climate among many parents of teens in the U.S., who often discourage nonmarital sexual behavior, especially when it may result in an unwanted pregnancy. Although there are important cultural and contextual differences between the U.S. and other developed countries, we think that the processes identified in this study may be applicable to the ways that teens in a variety of contexts negotiate conflicting norms in developing their own sexual norms and behaviors.

2.2 Age Norms

Although a variety of disciplines have contributed to the literature on social norms, we use the sociological definition of age norms as group-level expectations about behaviors that are considered appropriate at different stages in the life course (Neugarten, Moore, & Lowe, 1965; Settersten, 2003). Neugarten and colleagues (1965, p. 711) have written that “age norms and age expectations operate as prods and brakes upon behavior, in some instances hastening an event, in others delaying it.” Individuals internalize these age-based brackets for behavior and will readily describe themselves as “early” or “late” when they diverge from the expected timeline or sequencing of events (Neugarten, et al., 1965). In the past few decades researchers have documented a relative destandardization of age norms for younger cohorts with more diversity and tolerance for variation in the timing and sequence of life course transitions in late adolescence and early adulthood, but age norms persist (Rindfuss, Swicegood, & Rosenfeld, 1987; Shanahan, 2000). A defining feature of a social norm is the sanctioning that results from breaking it (Marini, 1984; Settersten, 2003). Simply the threat of negative sanctions attached to violating a social norm may be enough to keep individuals from violating that norm (Herold, 1981; Mollborn, 2010; Wooten, 2006). Even in the absence of sanctions, age norms are often followed because they have been internalized and are taken for granted (Billari & Liefbroer, 2007; Heckhausen, 1999).

Although individuals may not always conform to group norms or cultural ideals about appropriate behavior, the group’s consensus about which behaviors are appropriate produces and reinforces the norms, expectations, and sanctions that regulate individual behavior (Geronimus, 2003). Social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) suggests that individuals gauge the appropriateness of behaviors by observing the behaviors and social approval cues of others in their midst (Cialdini, 2001; Rimal & Real, 2005). An individual is more likely to be influenced by members of a particular reference group when s/he identifies closely with the group (Kirby, 2001a; 2001b; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005).

2.3 Variation in Norms about Sexual Behavior

Norms about the appropriate timing and context of teen sexual behavior vary by gender (Carpenter, 2002; Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009; Martin, 1996). The sexual double standard is based on the belief that men are encouraged and even expected to pursue sexual opportunities with women regardless of the context, while women are expected to avoid casual sex and have sex only when in a relationship, and preferably, when in love (Crawford & Popp, 2003; Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009; Risman & Schwartz, 2002). Fear of stigma may constrain young women’s sexual preferences and behaviors (Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009; Tolman, 1994). Much research has demonstrated that prescriptions for and proscriptions against teen sex may differ for teen boys and girls (Albanesi, 2010; Blinn-Pike, 1999; Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998; Eyre & Millstein, 1999; Leigh, 1989). However, others have argued that gender may be losing its ability to shape the experiences of virginity loss and, perhaps, sexual careers in general (Carpenter, 2002) and that over time boys’ sexual behavior has increasingly resembled girls’ behavior (Risman & Schwartz, 2002).

In addition to gender, researchers have identified the level of sexual experience as an important factor in teens’ sexual intentions and behaviors (Gillmore, et al., 2002; Nahom et al., 2001). For example, in a study of high school students, Gillmore and colleagues (2002) found that sexually experienced teens were more likely to base their intentions to have sex on their own attitudes, while virgins gave greater credence to social norms. However, virgins’ intentions to remain virgins more successfully predicted their sexual behaviors than did sexually active teens’ intentions to have sex (Gillmore, et al., 2002). In other words, virgins were more successful at remaining virgins than sexually experienced teens were at having sex. In another study, Nahom and colleagues (2001) found that sexually experienced teens felt significantly more pressure to engage in sex and perceived that significantly more of their friends were having sex than did virgins. Both of these studies also found significant differences by gender, particularly when teen boys and girls were grouped by level of sexual experience.

2.4 Influences on Teenage Sexual Behavior

We understand there to be at least three interconnected levels of social influence on behavior: individual, interpersonal, and institutional or structural (Risman, 2004). Many scholars have investigated structural-level factors that are related to teens’ engaging in early sexual behavior, such as race, ethnicity, social class, and nativity (Bettie, 2003; Collins, 2000; Gillmore, et al., 2002; Gonzalez-Lopez, 2005; Plummer, 2003). Others have investigated how individual-level constructs such as self-esteem, planful competence, and educational aspirations influence teens’ sexual decisions and outcomes (Billy, Brewster, & Grady, 1994; Clausen, 1991; Goodson, Buhi, & Dunsmore, 2006; Lauritsen, 1994; Small & Luster, 1994). As in many other areas of sociology, the interactional level has been relatively neglected (Emirbayer, 1997).

In this study we focus primarily on the interactional level, investigating the relative influence of three reference groups: parents, close friends, and other peers. Much research has demonstrated that each of these reference groups’ norms, expectations, and sanctions have significant influence on teens’ decisions about whether to have sex; however, the relative influence of these groups has not been clearly elucidated, as few studies have investigated both parental and peer influences (Whitaker & Miller, 2000)2. There is little research investigating how all three of these groups work in tandem to influence teens’ sexual behaviors.

Much research has linked the norms, attitudes, and behaviors of peers to teens’ sexual behavior (Brooks-Gunn & Furstenberg, 1989; DiClemente, 1991; Kinsman, et al., 1998; Sieving, et al., 2006). Yet, few scholars have investigated how social norms are translated into behavioral change (Kinsman, et al., 1998). Prevalent behaviors, which may or may not reflect social norms (Marini, 1984), have been shown to be important for understanding teens’ sexual behaviors. In a study of sexual initiation among sixth graders, Kinsman and colleagues (1998) found that the most important peer norm predictor of intention to initiate sex in the next year was adolescents’ perceptions of the prevalence of peers’ sexual behavior. Young adolescents were much more likely to report an intention to initiate sex and were more likely to actually initiate sex if they perceived that most of their peers were having sex (Kinsman, et al., 1998). Studies have also linked reputation-based popularity among peers (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003) and dating behaviors and experiences (see Kirby, 2002 for a review) with a higher risk of teen sex. A few studies have investigated the relative influence of close friends on teens’ sexual behaviors. In a study of African-American urban youth, Harper and colleagues (2004) found that close friends played a significant role in adolescents’ conceptualizations of dating and sexual behavior and in helping youth to acquire dating and sexual partners. In a related study, using nationally representative Add Health data, Sieving and colleagues (2006) found that teens were more likely to experience sexual debut if they believed they would gain their friends’ respect by having sex and if a greater proportion of their friends were sexually active. These studies all stopped short of examining the influence of both close friends and other peers.

The relationship between parental influence and teen sexual behavior is less straightforward. Gillmore and colleagues (2002) found that beliefs about the expectations of reference groups, such as parents, influenced high school students’ perceptions of social norms about sex, thus indirectly impacting their decisions about whether to have sex. In a study of age norms about another transition to adulthood, leaving home, Billari and Liefbroer (2007) found that perceptions of societal norms were not influential in young people’s decisions but that perceptions of the opinions of significant others (such as parents) were influential in decisions about leaving home. Other scholars have argued that parents have little or no influence over teens’ behaviors (Harris, 1995). There is a wealth of research on parent and teen communication about sex and teens’ risk behavior (Aspy et al., 2007; DiClemente et al., 2001; Hutchinson, Jemmott, Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2003; Teitelman, Ratcliffe, & Cedarbaum, 2008), but there is little information elucidating the processes through which parental norms about sex are communicated to teens (Gillmore, et al., 2002; Jaccard & Dittus, 1993; Whitaker & Miller, 2000). We address this gap in the literature directly by exploring the ways that parents communicate or convey their attitudes and beliefs about teen sex with their teen in both explicit and implicit ways.

3. The Study

Our study draws on 47 in-depth qualitative interviews with college students at a large public university in the western United States about their experiences with sex, contraception, and pregnancy as teenagers. Rather than generalizing findings to a broader population, the goal of the research was to explore teens’ narratives and experiences in order to elucidate complex processes underlying the relationships between social influences and sexual behavior that have been identified in quantitative research. This in-depth information is intended to inform future research using larger, more representative samples across contexts. The larger project’s interviews, which received institutional review board approval, were conducted in two phases. In the first phase, 43 interviews were conducted by trained undergraduates in two upper-level Sociology classes in 2008–2009. After receiving training on conducting qualitative interviews, students were asked to recruit a college student acquaintance and interview her or him.3 Students transcribed the interviews and submitted a transcription, an audio file of the interview, and their field notes. England and colleagues (2008) have successfully used peer interviewing techniques for sensitive topics, such as teen sex, that may result in more open disclosure with a familiar peer interviewer than with an older stranger. We believe that this strategy was justified for our project because participants apparently did reveal more sensitive information to the peer interviewers. For example, two participants disclosed previous pregnancies and abortions to the peer interviewers, but none did so to adult interviewers.

In the second phase of data collection, we employed a purposive sampling strategy and conducted interviews that were somewhat longer and less structured. A female research team consisting of a faculty member, a graduate student, and an undergraduate student conducted interviews with 14 undergraduates, who were recruited through a campus-wide email list and paid $10. During recruiting, students were asked whether they were first-generation college students or came from a rural or poor community. Half of the selected participants had these background characteristics, which were rare in the first phase of data collection. The others were chosen from the broader pool of recruits. Although the participants and interviewers were strangers and disclosure of sensitive information may therefore have been dampened, this phase of data collection permitted us to go into greater depth in probing about important themes that arose in the first round of interviews. This strategy of “abduction” (Reichertz, 2010) is useful for developing and testing theoretical ideas as they evolve.

The interviews were semi-structured, combining a list of questions that the team asked of every participant (in both phases of data collection, except for a section on available resources that was asked in the first phase and omitted in the second) with probe questions tailored to each interviewee. The depth of probing varied in the student-conducted interviews from the first phase, but in the second phase the individualized probing was extensive. Topics covered included participants’ perceptions when they were in high school of norms about teenage sex, contraception, and childbearing in their peer groups, families, communities, and society at large; how these norms influenced their own and their close friends’ and other peers’ fertility choices and behaviors; and what sanctions they faced as violators of these norms. We asked about their communication with parents, close friends, and other peers about these issues, as well as any stories they were told about peers’ experiences. In the second round of interviews, we also asked participants to compare sexual norms and behaviors from when they were in high school to those in college. While the bulk of the interview concerned events and attitudes from the past and was therefore probably subject to some degree of recall bias (Graham, Catania, Brand, Duong, & Canchola, 2002), participants’ high school experiences were still fairly recent, and they seemed to have little trouble remembering them.

Of the 57 college student participants, 47 (30 women and 17 men) came from mid- to higher SES backgrounds, defined as either of their parents having attained a college degree or holding a managerial or professional job. Because we found that teen sex, contraception, and pregnancy norms and behaviors differed considerably by community SES and because many college-bound lower-SES teens reported feeling like anomalies in their communities, we focus here only on the higher-SES group, drawn from both the first and second phase of interviews. In being college-bound, these participants were typical of teenagers in their communities. All but one (who was South Asian/Indian) self-identified as White or Caucasian, all identified as straight or heterosexual, and their ages ranged from 19 to 24. This sample composition was a little less diverse than the student population from which it was drawn, but it reflects the demographics of the vast majority of students at this university. There is a great deal of regional variation, as participants attended high school in 15 different states. They identified the communities where they attended high school as ranging politically from very conservative to very liberal. We group respondents based on their report of whether they were sexually active during high school, and this differed by gender with 16 females and 5 males remaining virgins, while 14 females and 12 males gained sexual experience during high school.

All interviews were transcribed and entered into the QSR NVivo qualitative software package. Transcripts were then coded using three techniques. First, responses were coded according to the question the participant was answering, including simple distinctions between answers (e.g., positive versus negative attitudes toward teen sex among close friends). Second, both authors read entire transcripts and identified important themes that emerged from the data, which were then identified and coded in other transcripts. Third, we identified key characteristics of respondents and compared findings across categories. Participants’ level of sexual experience in high school emerged as important for understanding the findings through this process. Using each of these analytic tools, we brought together our findings on norms about teenage sex, contraception, and pregnancy and their links to teens’ behavior. While pregnancy-related norms and behaviors are not the main focus of this study, the specter of pregnancy was clearly salient for participants and shaped sex and contraception norms, attitudes, and behaviors.

4. Results

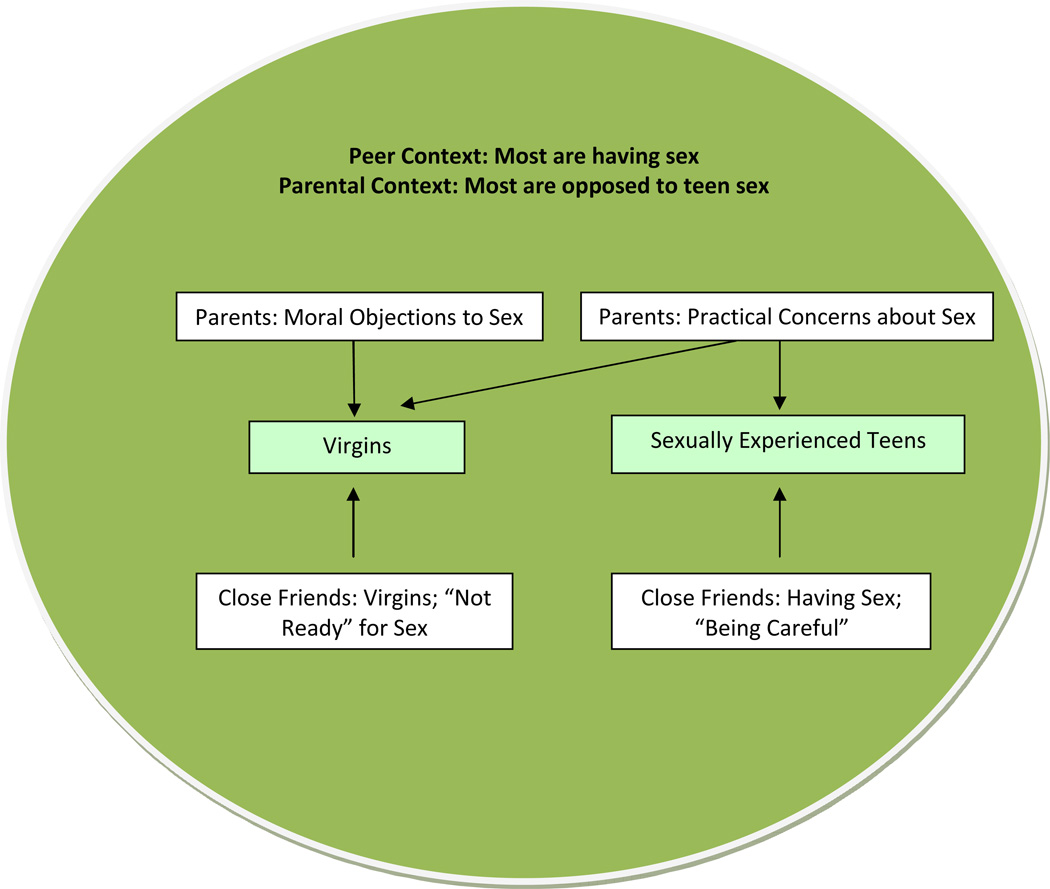

Our findings focus on norms about sex that were communicated to college-bound teens by parents, close friends, and other peers. Figure 1 illustrates the normative context of college-bound teens’ decisions about sex that arose in our data. Most teens in our sample perceived very similar peer and parental contexts in that they estimated that most peers were having sex and parents were against sex; however, there were important differences in the type of parental objection or concern about teen sex and in close friends’ sexual norms, depending on teens’ level of sexual experience. Virgins more often described parents as morally opposed to teen sex and close friends as “not ready” for sex. Thus, virgins perceived that they were negotiating competing norms from peers (encouraging sex) and parents and close friends (against sex). Sexually experienced teens, on the other hand, more often described their parents as opposed to teen sex for practical reasons, while their close friends were sexually active and “being careful” (i.e., using contraception). These teens, then, were negotiating competing norms from parents (against sex) and peers and close friends (encouraging sex).

Figure 1.

Perceived normative context of college-bound teens’ decisions about the transition to sex

In the sections below, we first describe virgins’ and sexually experienced teens’ and their close friends’ and other peers’ norms about sex. We differentiate between teens’ close friends and other peers because teens described these groups and their norms as distinct. Although close friends are a subset of teens’ larger peer networks, teens described close friends as confidants and peers as more distant classmates. Unlike in later sections, we separately examine the differences in the influence of age norms for virgins and sexually experienced teens because there was substantial variation in the ways these groups perceived the influence of age norms and sanctions on their sexual behaviors. We then turn to the ways teens communicated about these issues with their peers and close friends. Finally, we shift our focus to teens’ perceptions of parents, outlining two primary motivations for parental objections to teen sex and describing the ways parents communicated their objections and concerns about sex to teens.

4.1 Age Norms among Virgins: Being “Ready”

Many college-bound virgins in our study demonstrated a subjective understanding of an age norm proscribing sex – often until marriage – through their preoccupation with being “ready”. For these teens, making sure one was ready to have sex felt like an individualized process, at times influenced by outside forces like parents and close friends. Being ready was often defined by age and emotional maturity although some teens emphasized the potential risks of sex, especially negative sanctions from peers that would damage one’s reputation. This focus on age and maturity is similar to what Regnerus (2007) defined as “emotional readiness” in his study of religious youth and sexual behavior. According to Regnerus’s respondents, emotional readiness consisted of not only “being ready,” but also realizing “what you’re getting into” and being “old enough to handle the complex emotions of sex” (2007, p. 110). Many virgins in our study described sexual readiness in similar ways. For example, Sophie (female, virgin) stressed the importance of age:

I think for me at least it was just that they’re doing this and I’m not. It’s something I’ve thought about but never done before and is still really new to me and strange I guess, so there’s that aspect of just being something different and perceived as older than what I was doing.

Haylie (female, virgin) also emphasized age in her sense of readiness:

I mean, it was more that I just didn’t think about it as much or see myself doing it yet, like when I thought about it, well, like someday it will happen but right now it’s not and that’s OK…

Emotional maturity was also highlighted as important in virgins’ calculations about whether to have sex. For example, Ella (female, virgin) said that she didn’t think she was “old enough or mature enough to handle it either.” Similarly, Adrian (male, virgin) said that the sexually active teens were the ones “who wanted to be more mature than they really were or thought they were more mature.” According to Liam (male, virgin), “people were more scared of the institution of sex than they were of the results of it being pregnancy,” reflecting that it was not just the consequences of sex that intimidated or frightened teens, but the act of sex itself. These data indicate that for many college-bound virgins, the process of deciding whether one was ready for sex was seen as individualized, indicating that teens had internalized age norms about sex. Teens calculated whether they felt they were old and mature enough to have sex and whether they thought they would be able to handle the situation and the complex emotions that might be evoked.

Many virgins also based their decisions about sexual readiness on the potential consequences of sex. Some emphasized pregnancy, while others feared negative sanctions from peers that might result from public knowledge of their sexual activity (notably, STIs were not frequently perceived as a salient risk). Regardless of which was emphasized, the threat of consequences was enough for many college-bound virgins to decide that they were not ready to have sex during high school. For example, Violet, (female, virgin) described her fears about the consequences of sex:

Well, to be honest with you, it scared the shit out of me. I saw this fifteen-year-old girl that was pregnant walking around with a huge belly on her and I was not ready for that. I didn’t have my first boyfriend until I was a senior so that was never really a concern. And of course guys are going to be pushy and ask but, you know, it wasn’t hard for me to think, you know, do I want to have sex and possibly have a baby or just not until I’m ready?

Pregnancy was clearly salient in Violet’s decision to abstain from sex. This risk was not just a concern for teen girls. For instance, Logan (male, virgin) said:

I'm sure if I had ever gotten to a point where I was really … if I was ever put in a position where, [laughs] it sounds so corny, but sex was an imminent type of deal, the fact that pregnancy is a possibility would have been a pretty main deterrent before crossing the finish line.

Adrian (male, virgin) agreed that the risk of pregnancy played a role in abstaining from sex: “Like, it’s not really worth it, the risks … even if you are being careful, like you probably won’t get pregnant, but it’s not something you want to worry about.” Thus, both teen boys and girls were concerned about the possibility of an unplanned pregnancy, and this risk was enough to delay sexual activity until they felt ready.

For many college-bound virgins, pregnancy was not the greatest risk. Several focused instead on the danger of others finding out about their sexual activity and how this might damage their reputation. This concern was much more salient for virgins than sexually experienced teens in our sample: Twice as many virgins as sexually experienced teens said that a major risk of sex was being labeled a slut or having your reputation ruined. In line with the sexual double standard, teen girls were more worried about this risk than teen boys. Madelyn’s (female, virgin) quote about her friends captures this well:

They were worried about parents finding out, their reputation at school usually, what other people would think of them … I feel like a lot of the kids who [had sex], they didn’t even think about the chance of getting pregnant, like I could see a lot of kids not even considering that; it’d be more in the time, in the moment, of reputation, people finding out and stuff like that.

This comment reflects that, for many virgins, the risk of damaging their reputation was more salient in the decision to abstain from sex than of the risk of pregnancy. Of course, one of the obvious physical markers of teen sex would be a later-term pregnancy. Madelyn (female, virgin) described how this outcome could ruin one’s reputation:

I think it was because they were sexually active and then the whole school knew about it sort of kind of deal, ‘cause I knew other kids that were sexually active but like it wasn’t broadcast, because sex is something you just don’t talk about in our high school, so that’s why it damaged their reputation.

(So it was basically making their sexual activity public?)

Yeah.

Significantly, Madelyn argued here that it was the public knowledge of sexual activity, and not pregnancy per se, that would damage a sexually active teen’s reputation. Claudia (female, virgin) agreed with Madelyn that the public knowledge of sexual behavior was influential teens’ reactions to a pregnancy:

Well, I think that sex is something that happens privately and pregnancy is something that happens publicly, so they kind of exist in different realms in our thoughts, so whether or not we say we are OK with it or not OK with it either in sex or in pregnancy, that behavior really changes whether or not it is something that everyone is going to know or not. ‘Cause, I mean, you can even say, "I’m OK with people having sex, I don't care about it," and you don't ever have to yourself, you don't ever really have to get into that situation. And again, you could say, "I wouldn't mind if one of my friends was pregnant," and you might respond totally differently because you would have to deal with that in a more public setting.

Claudia’s comment clearly connects the ways that public knowledge about sexual behavior, in this case through a pregnancy, could impact the ways that teens thought about and acted in regards to sex. For these college-bound virgins, one of the most significant risks of having sex was the sanctioning that would occur if other people found out. This fear of negative sanctions is evidence that there was a group age norm at work, even though these teens viewed their decision to abstain from sex as individualized.

A minority of virgins in our sample, especially boys, described their lack of sexual readiness as determined in large part by their religious conviction and moral opposition to sex before marriage. This is evidence of a situational norm regulating the marital context of sex. For example, Aaron (male, virgin) was very involved with his local Christian youth group and said that he remained a virgin during high school because “before marriage, abstinence was the only option.” Similarly, Adrian (male, virgin) said that he abstained from sex during high school because of “personal beliefs and fears,” combining his belief in marriage as the appropriate context for sex with fears of an unplanned pregnancy. When asked if his personal beliefs were primarily religious, Adrian said, “I would say more religious but not completely. Like, I was brought up religious but I’m sure I had a weight on that… but if I wasn’t religious in high school, like if I stopped being religious, I don’t think that I would necessarily change.” Thus, although Adrian attributed the origin of his personal belief in abstinence to religious conviction, he internalized this belief as a subjective norm in much the same way as the virgins who described readiness for sex as an individualized decision.

Teens did acknowledge that these individualized decisions were not made in a vacuum. College-bound virgins relied on their close friends – often also virgins – whose sexual norms and behaviors complemented their own, in contrast to other peers who were sexually active (see Figure 1). Haylie (female, virgin) said, “My decision to not have sex was more based around myself not being ready and not being in serious relationships in high school, and then my friends also not having sex.” Violet (female, virgin) also reflected on this:

I actually got really lucky. We were very, not to say this is better than any other way, but we were all virgins long, far into high school, and I knew girls who were having sex when they were thirteen but they weren’t close friends of mine, they were just people I knew. So, the people I surrounded myself with were not, didn’t feel that pressure at all.

Aaron (male, virgin) also differentiated between the sexual norms and behaviors of close friends and other peers:

I mean as a high schooler, [sex] was something that was kind of like… I wouldn't say the forbidden fruit type of deal, but it was just something that was really separated, you know? I had one friend who played football and he would kind of switch between our group and the football players, and the stories he would tell, and the things that they did, just like worlds apart, you know?

Aaron’s comment demonstrates the differences in sexual behavior between his close friends, who were virgins, and other peers who had quite different sexual experiences. These comments highlight the ways that college-bound virgins considered their close friends’ sexual experiences in reinforcing their own choice to abstain from sex. These teens depicted their close friends as buffers against the sexual peer pressure that other teens (in other friend groups) experienced. This process could conceivably work in the opposite direction; that is, these teens may have decided to remain abstinent during high school and then chosen a group of friends who supported their beliefs. However, we do not have the data to address this issue.

These results demonstrate that college-bound virgins in our study were highly likely to talk about readiness for sex as an individualized process that was secondarily influenced by close friends. At the same time, though, many of their decisions were influenced by the threat of interpersonal sanctions, which indicates the existence of an unacknowledged age norm. These teens had internalized a set of age norms to the extent that they saw these norms as individualized “cognitive maps” guiding their behavior and perceived choices (Settersten, 2003). These individualized understandings, in turn, led to their viewing the choice to have sex as based on their own practical, moral, and religious beliefs and attitudes, rather than on larger group age norms. If these teens had viewed their choice as based on group age norms about the appropriate timing of sex, they might have been more likely to have had sex, since most of their peers were sexually active by the end of high school. Instead, their reasoning was closely related to their perceptions of their parents’ and close friends’ norms about teen sex, which were in accordance with their decisions. We discuss parental norms in greater detail below, but first we focus on sexually experienced teens’ age norms and teens’ communication about sex with close friends and other peers.

4.2 Age Norms among Sexually Experienced Teens: Being “Normal”

Unlike college-bound virgins, sexually experienced teens in our study talked explicitly about the influence of a group age norm that prescribed sex during high school as normal. Compared to virgins, these teens relied more heavily on close friends’ and other peers’ sexual norms and behaviors as guides for appropriate behavior; thus, many sexually experienced teens talked about having sex in high school as a normal part of teenage life and as a natural development in an intimate relationship. These teens felt more comfortable having sex because they knew that close friends and other peers had already taken that step and had faced few or no visible negative consequences (see Figure 1). Kara (female, sexually experienced), the first of her friends to have sex, reflected on how her peers’ views of her behavior changed as sex became normalized over the course of high school:

I mean, by the time I was a senior in high school, well, it changed through high school. When we started like freshman, sophomore year it was, when people started having sex, it was less accepted and I remember when I lost my virginity when I was 16 there were a lot of girls that looked down on me because I was not a virgin anymore. But by the time we were seniors in high school and we were 18, they were all having sex and they were having sex with way more guys, way more partners than I was ever, and their views on it had completely changed.

Helena (female, virgin) also talked about the normalization of sex during high school:

I guess, like, for most of high school people thought that there wasn't, like most people weren't having sex. But as we got into our senior year and stuff it was more like, you know, if people were having sex it wasn't as surprising anymore.

When asked if his peers were having sex during high school, John (male, sexually experienced) said, “I mean, in the beginning years of high school, no; towards the end, you know, junior and senior year, more definitely did [have sex].”

Some sexually experienced teens explicitly acknowledged that they relied on their close friends’ and other peers’ experiences as normative guides for their own behavior. For example, Kaitlyn (female, sexually experienced) said: “Once their friends have sex and start experimenting it starts to be OK. I mean, once everyone is doing it, you think it is OK. You start to think, everyone is doing it, so why am I not doing it?” In Carter’s (male, sexually experienced) high school, sex “was promoted more so than it was frowned upon.” And, Gavin (male, sexually experienced) said that he thought that “everyone [was] having sex” during high school. These quotes demonstrate that sexually experienced teens were aware of their peers’ sexual norms and behaviors during high school, which encouraged sex, especially for older students. These teens acknowledged that a group age norm was guiding their behavior. They also revealed a gender difference in norms with sex encouraged for some boys, although this was not always the case (as outlined above).

Some college-bound sexually experienced teens normalized their own and close friends’ sexual behaviors by focusing on the context of sex. In these instances, sex was viewed as normative when it took place in a relationship. Kaitlyn (female, sexually experienced) said, “Sex was a really common thing among all of my high school friends. I mean, it wasn’t anything that people put too much thought about. People were doing it, mostly in relationships.” Dylan (male, sexually experienced) said that sex was “always in a relationship.” Thus, although sexually experienced teens perceived a group age norm that dictated the appropriate time for sex, many also acknowledged that there was a situational norm at play in which sex was ultimately most acceptable within a relationship.

4.3 Close Friends’ and Other Peers’ Communication about Sex

Surprisingly, more than half of the virgins and sexually experienced college-bound teens in our sample who discussed communication with peers reported that they were largely silent about sex. For example, Charles (male, sexually experienced) said the norm was to keep talk about sex “behind closed doors.” And Helena (female, virgin) said, “No one really talked about [sex].” Despite this similarity, we also found notable differences in how virgins and sexually experienced teens talked about sex with close friends, in particular. Virgins were more likely to indicate that talking about sex with close friends was taboo, while sexually experienced teens more often reported having conversations about sex with close friends. For example, Aaron (male, virgin) said that among his close friends, sex was viewed as “essentially a bad thing. Or at least something that was taboo or shouldn't be talked about or ‖ or that [we] definitely shouldn't be involved in at that time.” Camryn (female, virgin) agreed: “We never really talked about [sex], like we didn't. I mean, I didn't really know of any of my friends who were having sex. Like I said, it was still, like that was all really private.” Ella (female, virgin) also indicated silence around sex when she said that she thought everyone around her was having sex: “I thought I was the only person who wasn't [having sex], but it turns out a lot of people actually weren't either.” This silence about sex among close friends is likely related to virgins’ fears of the potential damage to their reputation: Talking about sex might open the door to others’ finding out so it was much safer to avoid the topic altogether.

Sexually experienced teens were much more likely than virgins to report that they talked about sex with their close friends, even if the topic was avoided with other peers. Although there were some gender differences in this group and teen boys were more likely to talk about sex with close friends, it is important to note that both teen boys and girls limited their conversations to close friends that they trusted. Dylan (male, sexually experienced) said: “People only talk about that stuff with their best friend, people who you really trusted not to tell.” Finn (male, sexually experienced) agreed that teens would probably “tell a couple of close friends” about sex. Sexually experienced teen girls often reported that their close friends only broke the silence about sex when they needed help or advice. Veronica (female, sexually experienced) said that her friends were more likely to talk about sex “with other girls who were afraid they were pregnant or not getting their period or something like that.”

There were differences between virgins and sexually experienced teens in the likelihood of talking about sex with close friends and these differences are likely related to the threat of sanctions feared by virgins in our study. However, as we discuss below, both sets of teens were also aware of parents’ objections to teen sex, which probably resulted in discussions about sex among sexually experienced teens being limited to trustworthy friends. There were also gender differences in communication with close friends among sexually experienced teens. This may indicate that teen girls are faced with stricter norms and sanctions about sex, in general, which might limit their talk about sex even with their closest friends. Previous research has shown that young women’s sexual behavior may be constrained by fear of stigma (Hamilton & Armstrong, 2009; Tolman, 1994), and our findings go a step further by showing that the fear of stigma also impacted teen girls’ communication about sex, even with close friends. However, in the case of a crisis, such as a late period or suspected pregnancy, some teen girls broke the barrier of silence and talked to their close friends. Gaining support from friends in crisis situations can mean that girls are able to avoid talking about these issues with their parents (see below).

4.4 Parents’ Norms about Sex: Moral Objections and Practical Concerns

College-bound teens recognized the influence of parental norms about sex on their own sexual norms and behaviors. Both sets of teens overwhelmingly perceived that parents disapproved of teen sex during high school, leading to normative conflicts between parents, close friends, and other peers (especially for sexually experienced teens). Parental norms were particularly influential for virgins as demonstrated by virgins’ internalization of a norm against sex, while the sexual experiences of close friends and other peers seem to be more salient to sexually experienced teens. Parental disapproval of teen sex had strong implications for sexually experienced teens’ behaviors, though, as they worked hard to avoid negative sanctions from parents. Parents’ objections to teen sex largely reflected either a moral or a practical basis (see Figure 1). This split in parental objections to sex echoes Bearman and Brückner’s (2001) assertion in their study of virginity pledgers that critics of virginity pledges were more concerned with concrete negative consequences of teen sex, such as STIs and pregnancy, while pledge supporters were more likely to stress the “moral systems” that justified saying no to sex (p. 861). We find that Bearman and Brückner’s pledge supporters are akin to the moralizing parents of college-bound virgins, while the pledge critics’ practical concerns about sex are similar to those of some sexually experienced teens’ and virgins’ parents in our study. Dylan (male, sexually experienced) directly addressed teens’ perceptions of different motivations behind parents’ objections to teen sex prevalent in our sample:

From the parent's perspective it varied really diversely. I feel like my parents told me, “We understand that you're going to do this, but keep your consequences.” But other parents’ talks were like, “You don't do this, this is like wrong, religiously, morally. Like if you did this it would completely destroy our family,” type of thing. So, it really varied from parents.

Parents with practical concerns about sex were opposed to teen sexual behavior, but focused their energy on encouraging teens to avoid negative consequences, especially pregnancy, rather than on avoiding sex in general. On the other hand, parents with moral objections to teen sex focused on encouraging teens to avoid sexual behavior altogether because sex was viewed as morally wrong.

Moral objections to teen sex were often associated with religious beliefs that prescribed abstinence until marriage. Camryn (female, virgin) said:

So many of the families that I grew up with were really religious, and so they believed in abstinence only and that was it. So, I mean, there was no other option other than abstinence and if you deviated from that, then you were considered a deviant.

Similarly, Aaron (male, virgin) said according to the way he was raised, “Before marriage, abstinence was the only option.” Moral objections to teen sex were more common among parents of virgins, and in many cases, these values were shared by the teens themselves. For example, when asked why virgins avoided sex, Parker (male, virgin) said, “I believe it’s the morals that their parents instill in them as they grow up.” Bethany (female, virgin) also remarked on her and her friends’ values:

Well I think my group of friends, we all came from parents who taught us pretty much the same values: to respect your body, or respect yourself and be careful, and I am pretty sure we were all taught not to have sex, so I think we all came into it with the same values that we were taught so we viewed it in pretty much the same way.

Bethany uniquely combined moral objections and practical concerns about sex in her use of the rhetoric of “being careful.” We return to this in more detail below and discuss how “being careful” (coded language for contraceptive use) was more often used by parents who had practical concerns about teen sex. Isabella (female, sexually experienced) agreed that parents’ values were important in virgins’ postponing sex and that teens waited “because they knew their family values, or what their family would think of them if they had [sex].” These teens demonstrated an understanding and commitment to their parents’ norms about sex in their own decisions about sex during high school, and their focus on their families’ values indicates that they shared these moral objections with their parents.

Other parents had practical concerns about teen sex. Although teens perceived that these parents were against sex, they also noticed that parents focused more on their avoiding negative consequences, rather than on avoiding sex in general. For example, Alexis (female, virgin) said:

[My mother] really liked hypothetical situations in which really weird things happen. So like when we always, not always, but when we had those talks of adolescent-hood and stuff, then she would say things like “Yeah, and if you ever got pregnant then your dad and I would totally help you out, and if you wanted to get an abortion, OK, we would help you with that. But if you wanted [the baby] then you know, we would help you with that too, and it wouldn't be the end of the world or anything. But here are ways to prevent it, and you should do those instead.”

Isaac (male, sexually experienced) also reflected on this:

I knew those expectations of me, I knew how my community thought and my family thought about those issues, so the goal was certainly not to get pregnant. Yeah, I mean pregnancy, an unexpected pregnancy, was not a good thing.

Veronica (female, sexually experienced) referenced an age norm about childbearing: “We were probably really careful because we were raised by our parents who taught us that it's better to have a kid once you’re older.” As shown here, most parents who had practical concerns about teen sex reinforced the importance of having safe sex, being responsible, and avoiding pregnancy, although they did not condone sexual activity among teens. Importantly, these parents were more likely to communicate directly about sex with their teen, while parents with moral objections to sex often remained silent.

4.5 Parental Communication about Sex

Different parental norms about sex were related to different levels of communication about sex between parents and teens. Parents with practical concerns about teen sex were much more likely to address these issues directly, usually stressing responsibility (i.e., contraceptive use) and avoiding pregnancy. In other words, these parents taught their teen to “be careful.” Jessica (female, sexually experienced) said that although her parents were against her having sex, at the same time they “were realistic about it” and ultimately, she was careful because: “That's just how we were raised … to use protection.” Building on this, Patton (male, sexually experienced) said:

I mean, I know that personally my parents had a pretty open dialogue with me about having safe sex way before the thought of me having sex was in consideration. I feel like most of my friends’ parents were probably the same way because most of my friends had pretty good relationships, for the most part, with their parents in high school. So, I think it’s probably a combination of hopefully good parenting and understanding the consequences in our society of being a teen parent. Not that it’s necessarily always a negative thing, but it just makes… it limits your choices and can make it a lot more difficult. So, I think that was probably what kids were talking about with their parents.

Isabella (female, sexually experienced) said, “It’s never really been an option in my family to get pregnant early…I mean, we talked about it, but it was never really an option to have a child before I completed other things.” She went on to say that she and her parents “talked more about, like, contraceptives and preventative sexual education talks” and that her parents stressed the importance of completing her education and “getting yourself prepared to have a family.”

In contrast, virgins whose parents were morally opposed to teen sex often reported that parents were silent about these issues. For example, Alana (female, virgin) said that sex was a topic that “you don’t see … you don’t talk about it” with parents. Parker (male, virgin) said that his parents “would never talk about it with me.” Given this, how did virgins know how their parents felt about sex? Answers to this question were typically vague. Noelle, (female, virgin) said that her parents’ moral objections to sex were “just kind of understood” while Parker (male, virgin) said that he knew his parents were against teen sex “by the way I was brought up.” Other college-bound virgins, like Helena and Bethany agreed that their parents were silent about sex and said that despite this they knew that their parents were morally opposed to teen sex because of their family’s morals and values.

However, college-bound virgins’ parents were not the only ones who were silent when it came to sex. Some sexually experienced teens also reported that their parents were silent. For example, John (male, sexually experienced) said although he “know[s] my parents and how they would react,” which would be “not positively,” they had never talked about sexual issues. Similarly, Nadia (female, sexually experienced) said that although her mother, who was a nurse, never talked to her directly about sex, “She’ll make little comments on the side,” indicating that she did not approve of a teen pregnancy. Although some parents of virgins and sexually experienced teens were similar in their silence about teen sex, they still differed in their orientation to the issue. Despite the silence, sexually experienced teens viewed their parents’ concerns as focused on the potential consequences of unprotected sex, especially pregnancy. For example, Spencer (male, sexually experienced) said that although his parents “never talked specifically” about sex, his parents “stressed responsibility.”

Some sexually experienced college-bound teens actively hid their sexual activity from parents to avoid facing parents’ disapproval, thereby helping maintain silence about sex. Finn (male, sexually experienced) said, “Parents didn’t know anything. Parents were always really out of the loop.” And, Ella (female, virgin) said: “I know a lot of kids whose parents were really strict, but that just meant they'd have to try that much harder to sneak out and have sex with their boyfriend.” Henry (male, sexually experienced) agreed that a lot of people were unwilling “to address [sex] with their parents.” Despite knowledge of their parents’ objections and concerns about teen sex, sexually experienced teens continued to have sex. The fact that they worked to hide this behavior from their parents indicates that they were aware of their parents’ norms against sex, but that their close friends’ sexual norms and behaviors were more important influences on their own sexual behavior. However, parents’ norms against sex were salient in that teens hid their behavior to maintain silence with their parents about these issues. Isabella (female, sexually experienced) addressed this issue:

(So, do you think that the family’s opinion of teen sex or the peers of teen sex had more influence?)

Probably the peers overall. I mean, a lot of people weren't even really talking to their families about it. I think it totally depends on the family also, but the family's opinion would overall be that … hoping that teenagers would be not sexually active until a little bit later in life, but still providing information, knowing that most teens don't wait anymore, like that long. So, I think for the most part that families would play a small role, but definitely peers would have more of an impact on the teen's decision.

This strategy permitted sexually experienced teens to negotiate the competing norms of parents and close friends and other peers, by conforming to friend and peer norms behaviorally (i.e., having sex) while avoiding evidence of their nonconformity to parental norms against sex.

Interestingly, many college-bound teen girls accommodated parents’ concerns about responsibility by accessing birth control pills for reasons not ostensibly related to sexual activity. This strategy enabled parents and teens to avoid discussing sex directly. At the same time, young women who accessed birth control for non-sex reasons were safe from unintended pregnancy, which is likely to have appeased parents with either moral or practical concerns about sex. Sydney (female, sexually experienced) said:

A lot of the girls I knew were already on birth control. I was put on birth control when I was 18. I mean, most of the girls I knew were on it not just for sexual reasons but just because it was cool, I guess, to have regular periods. A lot of people were doing that.

Similarly, Nadia (female, sexually experienced) said:

When I wanted to get on birth control or something, I told my parents it wasn’t for that reason, like for sex. It was just to, like get more regular on my period or whatever. And, it wasn’t really something that I would directly talk to my parents about … and I think that was the same with my friends too.

Although not on birth control himself, Henry (male, sexually experienced) said: “Some girls were on birth control, but they might say it is so that it makes their periods lighter. That way, they didn’t have to address it [with their parents].” Birth control for ostensibly non-sex reasons was not only prevalent among sexually experienced teens in our sample. College-bound virgins also reported that they, their close friends, and other peers used birth control for non-sex reasons. For example, Noelle (female, virgin) said: “A lot of the girls were on the pill. People would start early for like cramps or to clear their face so they didn’t have to have the conversation with their parents if they’re already on the pill.” Bethany (female, virgin) agreed: “I know, like I was on the pill since eighth grade, but not because I was having sex, just for health reasons.” Accessing birth control for non-sex reasons was an effective behavioral strategy to maintain silence about sex between parents and teens and, at the same time, ensure that the girl was protected from unintended pregnancy, whether or not she was sexually active.

5. Discussion

These results demonstrate a complex relationship between college-bound teens’ sexual norms and those of their parents, close friends, and other peers. Despite very similar social locations and contexts in which teens perceived that most peers were sexually active and most parents were opposed to teen sexual activity, our evidence from in-depth interviews with 47 college-bound teen boys and girls suggests that different norms about sex were salient to virgins and sexually experienced teens in the development of their own sexual norms and behaviors. These groups of teens perceived age norms differently and navigated different sets of norms about sex from parents and close friends (see Figure 1). Both groups of teens in this study were impacted by social norms in their decisions about whether and when to have sex; the difference lay in how sexually experienced teens and virgins attributed their decisions.

College-bound virgins subjectively understood their decision to abstain from sex during high school as based primarily on an individualized decision about sexual readiness, even as they acknowledged the importance of avoiding the consequences of sex, especially pregnancy and negative sanctions from peers. Virgins described sexual readiness as influenced by age, emotional maturity, potential risks, and, for many, their parents’ and close friends’ views about sex, although both groups were often silent about sex. Although virgins did not acknowledge a group age norm, the fact that these teens viewed sanctions as important demonstrates the existence of an age norm for sex. Many studies of norms emphasize the importance of sanctions but focus less on the ways that individuals understand and internalize norms. These results demonstrate that it is not only sanctioning that influences behavior, but also individuals’ perceptions of the influence of social norms on their own norms and behavior.

In contrast, college-bound sexually experienced teens viewed sex during high school as governed by a group age norm prescribing sex as normal. These teens looked to their close friends’ and other peers’ sexual experiences to gauge the right time for sex and concluded that high school was indeed the appropriate time to transition into sex – especially if sex occurred in a relationship. Sexually experienced teens were likely to have close friends (and peers) who were also sexually active. These teens – especially boys – were more likely than virgins to talk about sex with close friends. Although previous research has found that boys boast about and exaggerate their sexual experience to reinforce their masculinity (Pascoe, 2007), these reports were scarce in our data. It is possible that this is because our sample is comprised exclusively of college-bound, primarily White teens who may instead engage in different strategies for managing their masculinity (Morris, 2008; Pike, 1996; Wilkins, 2008; Willis, 1981). Teen girls may face more sanctions for talking openly about sex which may have limited their communication with close friends.

We also found that college-bound teens perceived parents as significant influences in their decisions about sex, albeit in different ways. For virgins, parental moral objections to teen sex were important influences on their sexual norms and behaviors. In fact, many virgins expressed moral reservations about teen sex, indicating that they shared their parents’ norms. Sexually experienced teens more often described their parents’ concerns about sex as practical, emphasizing responsibility and avoidance of negative consequences, especially pregnancy. Our evidence shows that many teens felt their parents were silent on the issue of sex, especially when parents had moral objections. Parents with practical concerns about sex were more likely to talk openly with their teen about sex, and conversations usually focused on responsibility (contraceptive use). Although silence was often associated with parents’ moral objections to sex, it played other roles in sexual communication between parents and teens. Sexually experienced teens contributed to silence by hiding their sexual activity from parents. In some cases, teen girls accessed birth control for ostensibly non-sex reasons to preempt the need for communication about sex with their parents. In these situations, communication between teens and their parents was effectively ruled out, as teens either already had the tools to be careful (if they were on birth control) or did not let their parents know that they were having sex and needed information about being careful.

Providing access to birth control to teen girls for non-sex reasons is a useful strategy for parents with practical concerns about sex, as it allows parents to avoid direct and perhaps uncomfortable discussions about sex with their daughters while knowing they are protected from pregnancy. Parents with moral objections to sex are also negotiating a paradox in which they want their teens to be safe but do not want to talk openly with them about sex because of the moral implications. Both types of parents may want to voice their objections to teen sexual behavior at an age when their teen is statistically likely to start having sex; however, moral objections or discomfort may constrain them from doing so. Providing access to birth control (for non-sex reasons) protected teens from pregnancy while allowing parents to avoid discussions about sex. However, as noted below, although this strategy protects teen girls from pregnancy, birth control does not protect against STIs.

The majority of our respondents perceived that most of their peers were sexually active before the end of high school. Why did virgins and sexually experienced teens who shared very similar social locations and contexts end up behaving so differently in terms of sex? In this study, close friends were often the greater influence on teens’ sexual behavior when parents’ and peers’ norms did not match up. We found that for some virgins, especially those whose parents were not morally opposed to sex, close friends provided a link in explaining why these teens maintained their virginity while many of their peers had sex. Sexually experienced teens also recognized the importance of close friends and other peers in their decisions about sex, and often in a much more explicit way. For these teens, close friends’ and peers’ sexual behaviors were the marker by which normal sexual behavior was measured. Watching close friends have sex and avoid negative consequences (or at least visible ones) encouraged these teens to perceive high school as an appropriate time to transition into sex.

Thus, virgins and sexually experienced teens were navigating different sets of competing norms. Virgins perceived that parents’ and close friends’ norms were complementary and encouraged postponing sex – often until marriage – while other peers’ norms dictated that high school was an appropriate age for sex. Sexually experienced teens perceived that parents’ and close friends’ norms were opposed – parents were against sex and close friends’ sexual behaviors encouraged sex – and close friends’ norms were in accordance with other peers’ sexual norms and behaviors.

Significantly, virgins’ and sexually experienced teens’ close friends were usually similar to themselves in their level of sexual experience, even though both groups reported that most of their other peers were sexually active. This is similar to Giordano’s (1995) evidence that there are important differences between close friends and larger peer networks. Previous research has shown that teens exercise considerable agency in their choice of close friends in high school by choosing people who will support the goals they have and distancing peers with different goals and behaviors (Schneider & Stevenson, 2000). For college-bound virgins, surrounding oneself with like-minded friends may provide the push that some need to remain virgins during high school. This helps us understand how norms coexist with agency, as teens are agentically choosing close friends (and therefore their friends’ normative messages) based on their behaviors, and essentially turning peer pressure on its head. But they are doing it by drawing on a discourse of individualism that has important consequences. At the same time, parents are also active agents who influence teens’ choice of friends through the norms they instill in their children. Thus, parents’ and close friends’ norms are interrelated and likely to point many teens in the same direction.

Recent work has suggested that adolescents’ perceptions and attitudes are important factors for understanding why some teens transition into sex and others do not (Vacirca, et al., 2011). Our results underscore the importance of considering the joint influence of multiple reference groups and evaluating the ways that teens perceive these groups’ influences on their own norms and behaviors. The teens in our study clearly understood their decisions about sex as influenced by each group of significant others, albeit in different ways. These college-bound teens exercised considerable agency in negotiating between several different norms, some of which were complementary and some of which were competing. That teens are able to make sense of these different belief systems and utilize them in their decisions about whether and when to have sex demonstrates substantial levels of agency. These results are important to the teen-parent sexual communication literature because they show that much silence around sex was based on a fear of parental knowledge about teens’ sexual activity. Thus, we should continue to study sexual initiation because of the risks of negative consequences and because of its importance for adolescent and young adult sexual trajectories; however, we should also focus on the direction of information flow and who teens are talking to about their sexual behavior.

Although we offer several contributions, there are limitations to our study. First, our data are drawn from teen boys and girls who were graduated from high school and currently attending college. Therefore, these results may not be generalizable to the larger population of teens, including those who drop out of high school or do not go on to college. Further, there may be important distinctions in discourses and norms about sex related to different sets of parents, close friends, and other peers that we are unable to address here, such as whether sex is viewed as a casual matter or an important life course transition for teens based on SES differences. Second, although we include much regional variation in high schools in our sample, our respondents may not be typical of students in their high school or region. Additionally, because our sample is drawn from one western U.S. university, it may be biased towards students who chose that university for one reason or another. Third, we are unable to explore racial/ethnic variation in processes related to norms about teen sex in this primarily White sample. Finally, our study cannot address norms outside the U.S. context.

Our results provide an impetus for future research with representative quantitative data to generalize the relationships uncovered here. Our findings may be useful in several ways for policy experts and quantitative researchers focused on sexual behavior in this important phase of the life course. First, we demonstrate the simultaneous importance of parents, close friends, and other peers in college-bound teens’ decisions about sexual behavior. It is important not to assume that close friend effects and other peer effects are the same thing. Considering them separately may lead to inaccurate or incomplete understandings of norms and teen sexual behavior. We acknowledge that there are other important factors that influence these and other college-bound teens’ decisions about whether and when to have sex, especially structural factors such as religion and race and contexts such as neighborhoods and schools. Additionally, there are important opportunities and constraints that should be taken into account in teen sexual behavior. Dating is closely tied to teen sexual behavior (Kirby, 2002), and virgins and sexually experienced teens may experience different dating-related opportunities and constraints that work in tandem with norms to influence their sexual outcomes. Instead of isolating actors or contexts, our results motivate a multiple-context approach that considers different influences jointly. Nationally representative surveys such as Add Health are structured to accommodate these types of analyses.

Second, parental communication about sex is related to teens’ delayed sexual initiation and to an increase in birth control and condom use among sexually experienced teens (Aspy, et al., 2007; Martinez, Abma, & Copen, 2010). In this study of higher SES college-bound teens, we find that the content of communication with parents is very different for virgins and sexually experienced teens. When parents in this study did talk directly with teens about sex, teens perceived them as focusing on avoiding pregnancy: Putting daughters on the pill protects against pregnancy but not STIs, so this may be a particularly high-risk group for STIs if condom use is not consistent. Encouraging parents of higher-SES youth to talk directly about sex with their teen and to provide practical information about contraceptive use, including condoms, is likely to contribute to a reduction in the risk of STIs among teen girls and boys. In terms of future research, quantitative analyses that measure parent-teen communication based on the quantity of communication, rather than the content, are likely to miss important nuances in what parents are communicating to teens. Thus, it is not enough to control for the level of communication (i.e., whether parents talk with teens about sex). Furthermore, accurately estimating parents’ level of influence on teens’ behavior will require quantitative models that include diverse factors that are likely influenced by parents and shape teens’ sexual decisions, such as teens’ choice of close friends, their birth control pill use, and their attitudes toward sex.

Finally, recent research has demonstrated that parents more often talk to teen girls than boys about sex, especially during the early years of high school (Martinez, et al., 2010). Our results show that parents can be influential in their teen’s decision about whether and when to have sex, and thus, early conversations about sex with teen boys and girls are important and may thwart the silence that often results between parents and teens. Additionally, our results demonstrate that teens actively interpret their parents’ messages about sex and consider them in their decisions about whether and when to have sex. Future research should further investigate the extent to which teens view others as influential in their decisions. Social psychological literature has often focused on the individual or the dyad/group; however, we hope our results encourage researchers to focus on the joint influence of multiple reference groups.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this project were funded by the University of Colorado’s Innovative Grant Program and the University of Colorado’s Center to Advance Research and Teaching in the Social Sciences (CARTSS) Scholars program. The funding sources had no involvement in the conduct of the research and/or preparation of the article in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Thank you to Danielle Denardo, Laurie Hawkins, Kathryn McCune, Aleeza Zabriskie, and undergraduate interviewers for their assistance with the project and to Elizabeth Morningstar, Amy Wilkins, and Daniel Winchester for their comments on a previous draft.

Footnotes

In a closed-ended question during the background section of the interview, teens self-defined as having been “sexually active” in high school versus not. Thus, we are not categorizing teens by their experience with a specific behavior, such as penile-vaginal intercourse, but by their own definition of “sex.”

Gillmore and colleagues (2002) have investigated the relative influence of adult and peer norms in adolescents’ intentions to engage in sex and found that adult normative beliefs were significant predictors of the perceived social norm toward sexual behavior, while peer norms were not significantly related to perceptions of social norms about sex among adolescents.