Abstract

Recurrent miscarriage (RM) occurs in 1–3% of couples aiming at childbirth. Due to multifactorial etiology the clinical diagnosis of RM varies. The design of genetic/“omics” studies to identify genes and biological mechanisms involved in pathogenesis of RM has challenges as there are several options in defining the study subjects (female patient and/or couple with miscarriages, fetus/placenta) and controls. An ideal study would attempt a trio-design focusing on both partners as well as pregnancies of the couple. Application of genetic association studies focusing on pre-selected candidate genes with potential pathological effect in RM show limitations. Polymorphisms in ∼100 genes have been investigated and association with RM is often inconclusive or negative. Also, implication of prognostic molecular diagnostic tests in clinical practice exhibits uncertainties. Future directions in investigating biomolecular risk factors for RM rely on integrating alternative approaches (SNPs, copy number variations, gene/protein expression, epigenetic regulation) in studies of single genes as well as whole-genome analysis. This would be enhanced by collaborative network between research centers and RM clinics.

Keywords: recurrent miscarriage, genetics, epigenetics, study design, research and clinical collaboration, association studies, omic’s studies, placenta

Introduction

The occurrence of recurrent miscarriage (RM) has been estimated 1–3% of couples attempting to bear children (Berry et al., 1995; Rai and Regan, 2006; Branch et al., 2010). While fetal chromosomal abnormalities are responsible for 70% of sporadic miscarriages (Ogasawara et al., 2000; Philipp et al., 2003; Menasha et al., 2005), they account for considerably smaller fraction of pregnancy losses in RM couples. Today, clinical practice includes testing of several factors potentially increasing the risk of (recurrent) miscarriage, e.g., parental chromosomal anomalies, maternal thrombophilic, anatomic, endocrine, and immunological disorders (Bricker and Farquharson, 2002; Christiansen et al., 2008; Branch et al., 2010; Tang and Quenby, 2010). At least 50% of the RM cases have no deviations in any applied diagnostic test and are considered idiopathic, unexplained origin. In addition to clinical, environmental, and life-style risk factors, there is a growing evidence that RM has also genetic susceptibility. A review of initial observations indicated two to sevenfold increased prevalence of RM among first-degree blood relatives compared to the background population (Christiansen, 1996). Population-based register studies showed that overall frequency of miscarriage among the siblings of idiopathic RM is approximately doubled compared to general population (Nybo Andersen et al., 2000; Kolte et al., 2011). A recent genome-wide linkage scan using sibling pairs with idiopathic RM confirmed heterogeneity of contributing genetic factors (Kolte et al., 2011).

Unexplained RM is a stressful condition for a couple and supportive care is currently the only assistance that can be offered. Still, early recognition of a potential risk to miscarriage and systematic monitoring has beneficial effect in increasing live birth rates in RM couples (Jauniaux et al., 2006; Branch et al., 2010; Tang and Quenby, 2010; Musters et al., 2011). Genetic and genomic studies of RM have three main purposes: (1) identify DNA/RNA-based markers exhibiting direct predictive value to a couple’s risk to experience recurrent pregnancy losses; (2) capture the gene/protein expression profiles, pathways, and networks involved in (un)successful establishment of pregnancy; (3) apply hypothesis-based and hypothesis-free studies to pinpoint loci coding for novel non-invasive biomarkers applicable in clinical conditions for early pregnancy complications.

Challenges in Study Design to Investigate Genetics and “Omics” of RM

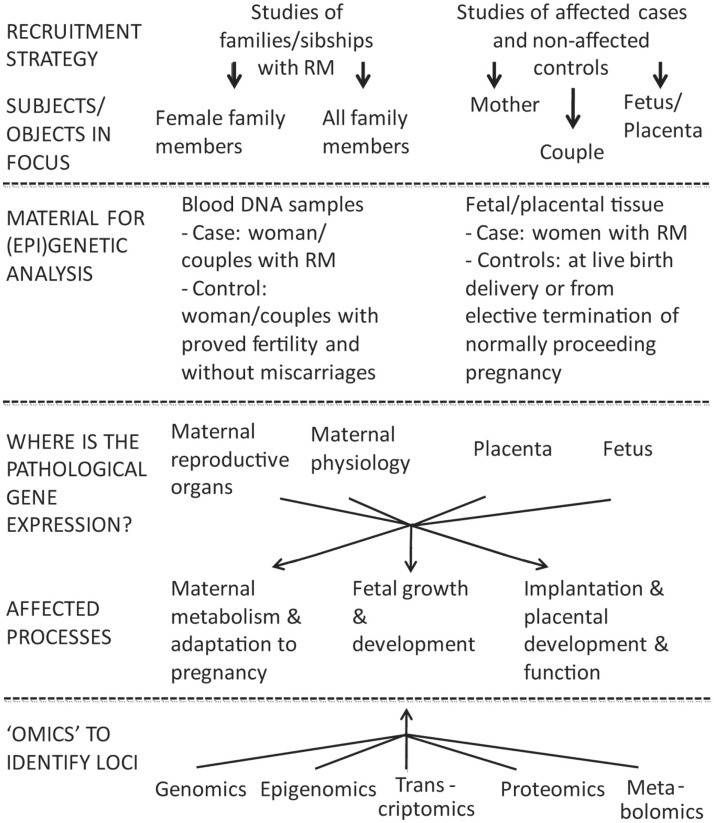

The design of genetic/“omics” studies to identify genes and biological mechanisms involved pathogenesis of RM is complex having several contradictory aspects regarding to the definition of phenotype, study objects, and functional effects to address (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Two broad options to investigate the inheritable component of recurrent miscarriage (RM) are family based linkage studies and comparison of unrelated cases and controls. For multifactorial diseases in adulthood the genetic association studies are superior compared to linkage analysis in pedigrees in terms of study design and power (Risch and Merikangas, 1996). In case of RM studies the addressed subjects/biological materials represent genetic material from two generations: mother–father and offspring(s), both providing own advantages and limitations. The affected processes are located in different compartments (mother–placenta–fetus) and involve aberrations in gene/protein expression influencing both maternal and fetal organisms.

Discrepancies in definition of the RM phenotype

Recurrent miscarriage is classically defined as the loss of three or more consecutive pregnancies before 20th gestational weeks (Berry et al., 1995; Jauniaux et al., 2006; Branch et al., 2010). Some experts consider two consecutive pregnancy losses sufficient for the diagnosis of RM because the recurrence rate and risk factors are similar to that after three losses (Branch et al., 2010). The faulty recall of the reproductive history, including or excluding the biochemical pregnancies (pregnancies documented only by a positive urine or serum hCG test) and center-specific ascertainment biases cause discrepancies in setting the diagnosis of RM (Christiansen et al., 2005).

The couples with RM can be divided into subgroups according to their reproductive history: primary (no successful pregnancies), secondary (series of miscarriages after a live birth) and tertiary (three non-consecutive miscarriages) RM and they should be considered as separate entities representing probably different pathophysiological mechanisms leading to pregnancy loss. Immunological factors have been suggested to play a greater role secondary RM, especially after the first-born son (Christiansen et al., 2004; Nielsen, 2011). Non-immunological risk factors, e.g., factor V Leiden mutation, tend to be associated mainly with primary RM (Wramsby et al., 2000).

The analysis power of genetics/“omics” research depends on the quality of the clinical history and applied diagnostic tests. Currently, the cases of idiopathic RM have been considered as preferred phenotype for the genetics research. However, the definition of idiopathic RM based on exclusions of known risk RM factors is facilities- and study-dependent. The association and/or causality of an etiologic factor with RM varies from “doubtful” to “definite” complicating the definition of idiopathic RM (Christiansen et al., 2005).

In summary, as RM is characterized by multifactorial etiology and variable penetrance and clinical outcome of recognized risk factors, a consensus in the clinical and research community has to be reached what factors should be tested before defining a particular case as idiopathic addressed via genetic/genomic studies.

Options for defining the study objects

One of the most challenging questions in investigating the genetics of RM is defining the study object(s): female patient and/or couple with miscarriages, fetus, or placenta (Figure 1). In genetic/genomic context these options target three different genomes (mother, father, fetus/placenta) and four (epi)genomes (different for placenta and fetus). In addition, as the definition of RM is based on longitudinal data (several independent events), one should remember that each pregnancy and each conceptus is a unique genetic combination with unique epigenetic settings, unique environmental conditions regarding the efficiency of established maternal–fetal interphase, maternal nutrition, and health.

Several genes that regulate implantation, fetal and placental development, and maternal adaptation to pregnancy are synthesized by the fetus or the placenta, e.g., placental hormones as hCG, placental growth hormone and lactogen (Mannik et al., 2010; Nagirnaja et al., 2010; Newbern and Freemark, 2011). In this context, a placental (fetal) genome would represent an ideal RM case for (epi)genetic and genomic studies. However, there are severe limitations–the recruitment of couples/women at the RM event and difficulties in obtaining pure tissue material from the aborted fetus with no contamination with maternal cells. There are some genetic studied focused on RM compared to control placentas (e.g., HLA-C, HLA-G, p53, mtDNA mutations; Table 1) but the sample sizes in these studies never reach required statistical power.

Table 1.

Genes targeted to genetic association studies in relation to RM risk.

| Gene name | Genetic associationa |

Main effect of the polymorphismc |

Key reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single study | Meta-analysis | Study casesb | Mother | Fetus/placenta | ||

| INFLAMMATION | ||||||

| IFNG | Y/N | Y/N | F | Bombell and McGuire (2008), Daher et al. (2003) | ||

| IL1B | Y/N | Y/N | F | Bombell and McGuire (2008) | ||

| IL1RN | Y/N | F | Choi and Kwak-Kim (2008) | |||

| IL1R1 | N | F | Traina et al. (2011) | |||

| IL4 | N | F | Kamali-Sarvestani et al. (2005), Saijo et al. (2004a) | |||

| IL6 | Y/N | Y/N | F | Bombell and McGuire (2008), Daher et al. (2003) | ||

| IL10 | Y/N | Y/N | F | Bombell and McGuire (2008), Daher et al. (2003) | ||

| IL12B | N | F | Ostojic et al. (2007) | |||

| IL18 | Y/N | F | Al-Khateeb et al. (2011), Naeimi et al. (2006) | |||

| IL21 | Y | F | Messaoudi et al. (2011) | |||

| TNFα | Y/N | N | F | Bombell and McGuire (2008), Daher et al. (2003) | ||

| TNFβ | N | F | Kamali-Sarvestani et al. (2005), Prigoshin et al. (2004) | |||

| TNFR1 | N | F | Yu et al. (2007) | |||

| THROMBOSIS AND CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM | ||||||

| ACE | Y/N | F | Goodman et al. (2009b), Zhang et al. (2011) | |||

| ACHE | Y | F | Parveen et al. (2009b) | |||

| AGT | N | F | Goodman et al. (2009b), Hefler et al. (2002) | |||

| ANXA5 | Y | F | Bogdanova et al. (2007), Miyamura et al. (2011) | |||

| APOB | N | F, C | Hohlagschwandtner et al. (2003), Yenicesu et al. (2009) | |||

| APOE | Y/N | F | Bianca et al. (2010), Goodman et al. (2009a) | |||

| AT1R | Y/N | F | Buchholz et al. (2004), Fatini et al. (2000) | |||

| EPCR | Y/N | F, C | Dendana et al. (2012), Kaare et al. (2007) | |||

| F2 | Y/N | Y/N | F, C | Kovalevsky et al. (2004), Silver et al. (2010), Toth et al. (2008) | ||

| F5 | Y/N | Y/N | F, C | Dudding and Attia (2004), Kovalevsky et al. (2004), Rey et al. (2003), Rodger et al. (2010), Toth et al. (2008) | ||

| FGB | N | F, C | Goodman et al. (2006), Yenicesu et al. (2009) | |||

| F12 | N | N | F | Sotiriadis et al. (2007), Walch et al. (2005) | ||

| F13A | Y/N | N | F, C | Coulam et al. (2006a), Sotiriadis et al. (2007), Yenicesu et al. (2009) | ||

| GPIa | Y | F | Gerhardt et al. (2005) | |||

| GPIIIa | Y/N | F, C | Ivanov et al. (2010), Pihusch et al. (2001), Yenicesu et al. (2009) | |||

| HMOX1 | Y | F | Denschlag et al. (2004) | |||

| JAK2 | N | F | Dahabreh et al. (2009) | |||

| MTHFD1 | N | F | Crisan et al. (2011) | |||

| MTHFR | Y/N | Y/N | F, C | Nelen et al. (2000), Ren and Wang (2006), Toth et al. (2008) | ||

| PAI-1 | Y/N | N | F | Buchholz et al. (2003), Goodman et al. (2009b), Sotiriadis et al. (2007) | ||

| PZ | Y/N | F | Dossenbach-Glaninger et al. (2008), Topalidou et al. (2009) | |||

| SELP | Y | F | Dendana et al. (2011) | |||

| TAFI | Y | F | Masini et al. (2009) | |||

| TGFB1 | N | F | Prigoshin et al. (2004), von Linsingen et al. (2005) | |||

| TM | N | C | Kaare et al. (2007) | |||

| TSER | N | F | Kim et al. (2006a) | |||

| VEGF | Y/N | F | Papazoglou et al. (2005), Traina et al. (2011) | |||

| ZPI | Y | F | Alsheikh et al. (2012) | |||

| DETOXIFICATION SYSTEM | ||||||

| AHR | N | F | Saijo et al. (2004b) | |||

| ARNT | N | F | Sullivan et al. (2006) | |||

| CYP1A1 | Y/N | F | Parveen et al. (2010), Saijo et al. (2004b) | |||

| CYP1A2 | Y/N | F | Saijo et al. (2004b), Sata et al. (2005) | |||

| CYP1B1 | N | F | Saijo et al. (2004b) | |||

| CYP2D6 | Y/N | F | Parveen et al. (2010), Suryanarayana et al. (2004) | |||

| GSTM1 | Y/N | F | Parveen et al. (2010), Sata et al. (2003a) | |||

| GSTP1 | Y/N | F | Parveen et al. (2010), Zusterzeel et al. (2000) | |||

| GSTT1 | Y/N | F | Parveen et al. (2010), Sata et al. (2003a) | |||

| NAT2 | N | F | Hirvonen et al. (1996) | |||

| CHROMOSOMAL SEGREGATION | ||||||

| SYCP3 | Y/N | F | Bolor et al. (2009), Hanna et al. (2011), Mizutani et al. (2011) | |||

| IMMUNE RESPONSE | ||||||

| CCR5 | Y/N | F | Parveen et al. (2009a, 2011b) | |||

| CTLA4 | Y | F, trio | Tsai et al. (1998), Wang et al. (2005) | |||

| CX3CR1 | Y | F | Parveen et al. (2011b) | |||

| HLA-A, B | Y/N | N | C, trio | Beydoun and Saftlas (2005), Christiansen et al. (1989), Kolte et al. (2010) | ||

| HLA-C | Y/N | N | F, C, P | Beydoun and Saftlas (2005), Faridi and Agrawal (2011), Hiby et al. (2010), Moghraby et al. (2010) | ||

| HLA-E | Y/N | F, C | Kanai et al. (2001), Mosaad et al. (2011), Steffensen et al. (1998) | |||

| HLA-G | Y/N | F, C, trio | Aruna et al. (2010), Cecati et al. (2011), Hviid et al. (2004), Kolte et al. (2010), Ober et al. (2003) | |||

| HLA-DPB1 | Y | C | Takakuwa et al. (1999) | |||

| HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1 | Y/N | F, C, trio | Aruna et al. (2011), Kruse et al. (2004), Steck et al. (1995) | |||

| HLA-DR′ | Y/N | Y | F, C, trio | Beydoun and Saftlas (2005), Christiansen et al. (1999), Kolte et al. (2010), Kruse et al. (2004) | ||

| INDO | N | F | Amani et al. (2011) | |||

| KIR | Y/N | F, C | Faridi et al. (2009), Hiby et al. (2008), Witt et al. (2004) | |||

| MBL | N | C | Baxter et al. (2001) | |||

| HORMONAL REGULATION | ||||||

| AR (and XCI)d | Y/N | Y | F | Karvela et al. (2008b), Su et al. (2011a) | ||

| hCG beta (CGB5/8) | Y | C | Rull et al. (2008) | |||

| CYP17A1 | Y/N | F | Litridis et al. (2011), Sata et al. (2003b) | |||

| CYP19A1 | Y | F | Cupisti et al. (2009), Suryanaryana et al. (2007) | |||

| PROGINS, ESR1/2 | Y/N | N | F | Su et al. (2011a), Traina et al. (2011) | ||

| PLACENTAL FUNCTION | ||||||

| ACP1 | Y | F | ? | ? | Gloria-Bottini et al. (1996) | |

| ADA | Y | F | ? | ? | Nicotra et al. (1998) | |

| ADRA2B | N | F | Galazios et al. (2011) | |||

| ANGPT2 | N | F | Pietrowski et al. (2003) | |||

| CD14 | N | F | Karhukorpi et al. (2003) | |||

| EG-VEGF, PKR1, PKR2 | Y | F | Su et al. (2010) | |||

| H19 | N | C | Ostojic et al. (2008) | |||

| IGF-2 | Y | C | Ostojic et al. (2008) | |||

| KDR | Y | F | Su et al. (2011b) | |||

| MCP | N | F | Heuser et al. (2011) | |||

| MMP9 | N | F | Singh et al. (2012) | |||

| NOS3 | Y/N | F | Karvela et al. (2008a), Parveen et al. (2011a) | |||

| P53 | Y/N | Y | F, C, trio | Coulam et al. (2006b), Kaare et al. (2009a), Pietrowski et al. (2005), Tang et al. (2011) | ||

| PAPPA | Y | F | Suzuki et al. (2006) | |||

| PGM1 | Y | C | Bottini et al. (1983), Nicotra et al. (1982) | |||

| STAT3 | Y | F | Finan et al. (2010) | |||

| TPH1 | N | F | Unfried et al. (2001) | |||

| MITOCHONDRIAL FUNCTION | ||||||

| Mutational burden | Y/N | F, C, trio | Kaare et al. (2009b), Seyedhassani et al. (2010), Vanniarajan et al. (2011) | |||

aY, positive association studies; N, negative studies.

bF, female RM patients; C, RM couple; P, placenta; trio, parents + fetus/placenta.

cFunctional effect coded by maternal genome (e.g., expression in endometrium) or by fetal/placental genome is shown with  ; ? specific localization of the effect not clearly determined.

; ? specific localization of the effect not clearly determined.

dSkewed X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) test is can be used to indirectly determine the association between androgen receptor (AR) CAG repeat expansion and RM (Su et al., 2011a).

ACE, angiotensin I converting enzyme 1; ACHE, acetylcholinesterase; ACP1, acid phosphatase 1; ADA, adenosine deaminase; ADRA2B, adrenergic, alpha-2B-, receptor; AGT, angiotensinogen; AHR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ANGPT2, angiopoietin 2; ANXA5, annexin A5; APOB, apolipoprotein B; APOE, apolipoprotein E; AR, androgen receptor; ARNT, aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator; AT1R, angiotensin II type-1 receptor; CCR5, chemokine receptor 5; CD14, CD14 molecule; CGB5, chorionic gonadotropin, beta polypeptide 5; CGB8, chorionic gonadotropin, beta polypeptide 8; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; CX3CR1, chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor 1; CYP1A1, cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A, polypeptide 1; CYP1A2, cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A, polypeptide 2; CYP1B1, cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily B, polypeptide 1; CYP2D6, cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily D, polypeptide 6; CYP17A1, cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1; CYP19A1, cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily A, polypeptide 1; EG-VEGF, endocrine-gland-derived vascular endothelial growth factor; EPCR, endothelial protein C receptor; ESR1, estrogen receptor 1; ESR2, estrogen receptor 2; F2, coagulation factor II/prothrombin; F5, coagulation factor V/factor V Leiden; F12, coagulation factor XII; F13A, coagulation factor XIII, A1 polypeptide; FGB, fibrinogen beta chain; GPIa, platelet glycoprotein Ia; GPIIIa, platelet glycoprotein IIIa; GSTM1, glutathione S-transferase mu 1; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase pi 1; GSTT1, glutathione S-transferase theta 1; H19, imprinted maternally expressed transcript (non-protein coding); HLA-A, major histocompatibility complex, class I, A; HLA-B, major histocompatibility complex, class I, B; HLA-C, major histocompatibility complex, class I, C; HLA-E, major histocompatibility complex, class I, E; HLA-G, major histocompatibility complex, class I, G; HLA-DPB1, major histocompatibility complex, class II, DP beta 1; HLA-DQA1, major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ alpha 1; HLA-DQB1, major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ beta 1; HLA-DR′, major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR loci; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; IFNG, interferon, gamma; IGF-2, insulin-like growth factor 2; IL1B, interleukin 1, beta; IL1RN, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; IL1R1, interleukin 1 receptor, type I; IL4, interleukin 4; IL6, interleukin 6; IL10, interleukin 10; IL12B, interleukin 12B; IL18, interleukin 18; IL21, interleukin 21; INDO, indole 2,3-dioxygenase; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; KDR, kinase insert domain receptor; KIR, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor; MBL, mannose binding lectin; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; MMP9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; MTHFD1, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; NAT2, N-acetyltransferase 2; NOS3, nitric oxide synthase 3; P53, p53 tumor suppressor; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; PAPPA, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A; PGM1, phosphoglucomutase 1; PROGINS, progesterone receptor; PKR1, prokineticin receptor 1; PKR2, prokineticin receptor 1; PZ, protein Z; SELP, selectin P; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; SYCP3, synaptonemal complex protein 3; TAFI, thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor; TGFB1, transforming growth factor, beta 1; TM, thrombomodulin; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; TNFβ, tumor necrosis factor beta; TNFR1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor 1; TSER, thymidylate synthetase enhancer region; TPH1, tryptophan hydroxylase 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor A; ZPI, protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor.

As a solution, an ideal study would attempt a trio-design focusing on both partners of clinically well-described RM couples as well as aborted cases and live born children (as inner control) of the same couple. This would allow to directly address parental- and allele-specific gene expression or epigenetic modifications in placenta. The paternally inherited genetic factors contribute and combine with maternally inherited factors in the placental/fetal (epi)genome (Rull et al., 2008; Faridi and Agrawal, 2011; Uuskula et al., 2011). So far, most studies of couples have been limited to parental karyotyping, and in case of a structural chromosomal abnormalities their effect on couple’s offsprings (Stephenson and Sierra, 2006; Franssen et al., 2011).

The identification of a suitable control group for women/couples with RM has its own great challenges. The ideal controls should be exposed to similar number of pregnancies at the same age of partners as the cases, and never experienced miscarriage. In a typical study the controls have been defined as women/couples with proven fertility when having at least one child, with limited information about their full reproductive history during the present or past partnerships. Delaying the childbirth until older reproductive age, the usage of contraceptive methods after birth of the one or two planned children, the change of co-habitant partners are frequent limitations for recruitment of the ideal control group.

Challenges in linking the genetic variants with the pathological functional effect

A successful pregnancy can be achieved only via balanced dialog between mother and the fetus mediated through placenta. The pathologies may locate and influence physiology in different compartments (Figure 1). In maternal side, RM has been associated with genes responsible for impaired endometrial decidualization, apoptosis as well as inflammatory processes (Salker et al., 2010). Multiple (epi)genetic/genomic factors decrease sperm quality causing DNA damage and thus leading to poor fertilization, impaired embryo development and possibly to RM (McLachlan and O’Bryan, 2010; Brahem et al., 2011). The development of placenta and release of placentally expressed proteins strongly influence both the fetal and maternal metabolism during the pregnancy (Fowden et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2012).

Genetic Association Studies of RM: Biases, Contradictions, Limitations

All conducted genetic association studies targeting RM have been designed as hypothesis-based candidate gene studies. The most frequently addressed genes in the context of RM are associated with the developing immunotolerance and inflammation and also with changes of maternal metabolism and blood coagulation (Table 1). Female partner of RM couple has been the most commonly addressed study subject.

The polymorphisms in almost 90 different genes have been investigated (Table 1). In most studies the association between a polymorphism and RM is negative, has not been replicated in follow-up studies or shows opposite results between studies. Inconsistencies may arise due to (i) differences in study design, definitions of RM and control group; (ii) focus on RM women instead of couples or placenta; (iii) low statistical power due to small sample size; (iv) ethnic difference in risk variants, population-specific low-impact gene variants increasing RM risk in consort; (v) contribution of life-style and environmental factors on the pregnancy course; (vi) secondary pathways affecting protein translation/metabolism leading to discrepancies between genotype and respective protein levels, e.g., Factor XII, Protein Z (Iinuma et al., 2002; Topalidou et al., 2009).

Most popular clinically tested polymorphisms in RM patients are thrombophilia-associated factor V (Leiden factor) mutation, factor II (prothrombin) G20210A mutation and MTHFR C667T variant encoding the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme with reduced activity. However, meta-analyses or large studies focusing on these factors in relation to RM risk have controversial results (Table 1). There is also uncertainty about prognostic implications of positive tests as full thrombophilia screen can produce abnormal results in 20% of women with uncomplicated obstetric histories (Branch et al., 2010; Tang and Quenby, 2010).

Another set of thoroughly investigated polymorphisms providing contradictory results in association with RM are in genes involved in inflammation (e.g., IL1B, IL6, IL10, IFNγ, TNFα; Table 1). The balance of locally produced pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines was suggested to be critical for successful pregnancy (Choi and Kwak-Kim, 2008). It was proposed that a spectrum of thrombophilic and inflammation related genetic variants rather than single polymorphisms shape the cumulative risk of RM (Rey et al., 2003; Jivraj et al., 2006; Christiansen et al., 2008).

The immunological mechanisms responsible for the development of the tolerance to semi-allogeneic fetal “graft” by the maternal immune system has been the third attractive target for genetic studies. Positively, a majority of association studies with immune response related genes have been conducted for RM couples (Table 1). Unfortunately, most reports on the studied gene variants in relation to RM are controversial. There are numerous studies on polymorphisms affecting the expression of HLA-G (e.g., 14 bp indel in exon 8 of the 3′ UTR), the most dominant HLA antigen in blastocysts and trophoblastic tissue. Recent analyses have suggested that specific combinations of fetal (paternal) HLA-C and maternal killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) gene variants correlate with the risk to RM and other pregnancy complications (Hiby et al., 2010; Chazara et al., 2011; Colucci et al., 2011). KIRs regulate activity of uterine NK cells that are implicated in trophoblast invasion.

During the last years the focus has gradually switched from maternal factors to the genes involved in the function of placenta, carrying maternally and paternally originated gene copies (Table 1). The investigators have targeted placenta-specific genes such as hCG beta coding CGB5 and CGB8, as well as loci with wider expressional profile but exhibiting a specific role in placental function such as PAPPA, IGF-2, and p53 (Suzuki et al., 2006; Ostojic et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2011). Although initial genetic studies have exhibited positive association between identified novel gene variants and an increased risk to RM, replication studies have to confirm these findings.

Advances and Future Directions in “Omics” and (epi)Genetics

Genetic association studies based on pre-selected candidate genes have shown their limitations as RM represents a complex phenotype with no identified major genetic factor(s). In order to achieve the main goal – to identify predictive genetic risk factors and biomarkers for RM, advances are needed in clinic as well as in the research strategies.

Recruitment strategy

Suggested advances in clinic include networking of research groups aiming to collect large sample-sets targeting RM phenotype under joint criteria and guidelines. Recruitment of both couples suffering from RM as well as controls should be encouraged, along with detailed clinical and reproductive history. Andrologists are to be involved to analyze reproductive parameters of male partners. Recruitment of duos (mother–placenta/fetus) or trios (mother–father–placenta/fetus) would provide further bonus. Studies should be enhanced by collecting the material for DNA, RNA, and protein studies from the same recruited family, e.g., parental blood samples, paternal sperm analysis, maternal endometrial tissue, multisite placental tissue sampling. A network of targeted clinics would facilitate carrying out validation of novel identified biomarkers by setting up the large multicentre studies.

Introducing “omics” into RM research

With rapidly evolving technological advances in genetics/“omics” there are multiple appealing perspectives in RM biomolecular research (Figure 1).

Up to now, no hypothesis-free genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for identification of common risk variants for RM have been performed. The main reason is that large number of uniformly defined RM affected individuals/couples is required to reach sufficient power in such heterogenous phenotype (Eichler et al., 2010). Copy number variations (CNVs) involving one or several loci are expected to exhibit a stronger effect on the phenotype compared to SNPs. Comparative genome hybridization-based microarray analysis of 26 euploidic miscarriages picked up 11 unique inherited CNVs, two of them involve genes TIMP2 (86 kb duplication) and CTNNA3 (72 kb deletion) that are imprinted and maternally expressed in the placenta (Rajcan-Separovic et al., 2010). The first results of ongoing study using genome-wide genotyping data to map common CNVs demonstrated significantly more frequent prevalence of a 52.4-kb locus duplication on chromosome 5 among RM couples in Estonian and Danish population (Nagirnaja et al., 2011). These pilot studies alert for further investigations of rare and common CNVs as risk factors for RM.

Transcriptomics and proteomics based gene expression profiling in tissues responding to ongoing miscarriage event offers an attractive approach to identify differentially expressed biomarkers (Baek et al., 2007). A decreased expression level in chorionic villi from RM patients was shown for angiogenesis related loci, whereas the expression of several apoptosis-related genes was increased (Choi et al., 2003; Baek, 2004). The first whole-genome gene expression profiling of placental tissue from RM compared to uncomplicated pregnancies identified and replicated significant differential expression of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TNFSF10; TRAIL) and S100A8 encoding for inflammatory marker calprotectin (heterodimer S100A8/A9; Rull et al., 2012). In comparative proteomics study applying 2-DE and MALDI-TOF/MS analyses of the follicular fluids of RM patients, abnormal expression of complement component C3c chain E, fibrinogen γ, antithrombin, angiotensinogen, and hemopexin precursor was reported (Kim et al., 2006b), and in the blood serum from RM patients the expression of ITI-H4 was altered (Kim et al., 2011).

Integrating of genetics and epigenetics

An important factor of placental development and function is epigenetic regulation governing the control of gene expression (Nelissen et al., 2011). Epigenomic marks include CpG methylation in DNA, histone modifications in chromatin, and non-coding regulatory RNAs. The specific features in placental epigenome are (i) active temporal dynamics – changes in epigenetic marks over course of pregnancy (Novakovic et al., 2011); (ii) complex organization of the DNA methylome and presence of tissue-specific differentially methylated regions (Choufani et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2011); (iii) abundance of parental-specific imprinted genes (Constancia et al., 2004; Moore and Oakey, 2011); (iv) evidence of polymorphic methylation or imprinting (Yuen et al., 2009); (v) placenta-specific microRNAs (miRNAs; Luo et al., 2009; Maccani and Marsit, 2009; Noguer-Dance et al., 2010); (vi) effect of environmental factors, e.g., maternal smoking (Maccani et al., 2010). Although altered placental epigenetics has been demonstrated in cases of fetal growth disturbances, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes (Nelissen et al., 2011), there is limited information on the role of aberrant epigenetic profiling in RM. Epigenetic comparison of different cell types in early pregnancy is technically challenging. The only systematically addressed topic is skewed X-chromosome inactivation (XCI; the preferential inactivation of one of two X-chromosomes in female cells). Initial findings that XCI is increased in women with RM were promising (Sangha et al., 1999; Lanasa and Hogge, 2000; Van den Veyver, 2001), but the follow-up studies have revealed that the skewed XCI is associated rather with maternal age and fetal karyotype than solely with RM (Hogge et al., 2007; Pasquier et al., 2007; Warburton et al., 2009). Only single studies are available for gene-specific methylation in RM-related tissues (placenta, endometrium, maternal blood). For the biallelically expressed hCG beta-subunit coding CGB5, three placentas (including two RM) were reported with monoallelic expression of maternal alleles and hemimethylated gene promoters suggesting the association of methylation allelic polymorphism with pregnancy loss (Uuskula et al., 2011). Methyl transferase (G9aMT) and methylated histone (H3-K9) expressions were significantly lower in decidual/endometrial tissue of unexplained RM cases compared to controls (Fatima et al., 2011). As a support to the contribution of epigenetic regulation of implantation, significantly more abnormal methylation values for APC and imprinted PEG3 were reported in chorionic villus samples of abortions/stillbirth than in other studied genes (Zechner et al., 2009).

No targeted microRNA expression profiling has been performed for RM-related tissues. Still, there are placenta-specific miRNAs capable of crossing the placental barrier and detectable in maternal plasma (Chim et al., 2008; Miura et al., 2010) and an altered profile of several miRNAs has been shown in pregnancy complications. Among the RM-associated genes, the expression of HLA-G was shown to be modulated by a 3′ UTR polymorphism exhibiting allele-specific affinity to microRNAs miR-148a, miR-148b, and miR-152, and consequently differential mRNA degradation and translation suppression processes (Tan et al., 2007). A recent study showed association between two SNPs in pre-miR-125a and increased risk to RM (Hu et al., 2011). As miRNA expression data has been suggested to harbor potential in discriminating disease samples with high accuracy (Scholer et al., 2011), there might be also strong perspectives in RM research and potential clinical implications.

In conclusion, future directions in investigating biomolecular risk factors for RM rely on integrating alternative approaches (DNA variants, gene and protein expression, epigenetic regulation) in studies of individual genes as well as whole-genome analysis. This would be greatly enhanced by extensive collaborative network between research centers and RM clinics.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The studies on the genetics of recurrent miscarriages in the laboratory of Maris Laan have been supported by Wellcome Trust International Senior Research Fellowship (070191/Z/03/A) in Biomedical Science in Central Europe, HHMI International Scholarship Grant #55005617, Estonian Science Foundation (grants #7471, #9030), and Estonian Ministry of Education and Science core grants SF0182721s06, SF0180022s12.

References

- Al-Khateeb G. M., Sater M. S., Finan R. R., Mustafa F. E., Al-Busaidi A. S., Al-Sulaiti M. A., Almawi W. Y. (2011). Analysis of interleukin-18 promoter polymorphisms and changes in interleukin-18 serum levels underscores the involvement of interleukin-18 in recurrent spontaneous miscarriage. Fertil. Steril. 96, 921–926 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsheikh F. S., Finan R. R., Almawi A. W., Mustafa F. E., Almawi W. Y. (2012). Association of the R67X and W303X nonsense polymorphisms in the protein Z-dependent protease inhibitor gene with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 18, 156–160 10.1093/molehr/gar069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amani D., Ravangard F., Niikawa N., Yoshiura K., Karimzadeh M., Dehaghani A. S., Ghaderi A. (2011). Coding region polymorphisms in the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (INDO) gene and recurrent spontaneous abortion. J. Reprod. Immunol. 88, 42–47 10.1016/j.jri.2010.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruna M., Nagaraja T., Andal Bhaskar S., Tarakeswari S., Reddy A. G., Thangaraj K., Singh L., Reddy B. M. (2011). Novel alleles of HLA-DQ and -DR loci show association with recurrent miscarriages among South Indian women. Hum. Reprod. 26, 765–774 10.1093/humrep/der024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruna M., Sudheer P. S., Andal S., Tarakeswari S., Reddy A. G., Thangaraj K., Singh L., Reddy B. M. (2010). HLA-G polymorphism patterns show lack of detectable association with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Tissue Antigens 76, 216–222 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek K. H. (2004). Aberrant gene expression associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 10, 291–297 10.1093/molehr/gah049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek K. H., Lee E. J., Kim Y. S. (2007). Recurrent pregnancy loss: the key potential mechanisms. Trends Mol. Med. 13, 310–317 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter N., Sumiya M., Cheng S., Erlich H., Regan L., Simons A., Summerfield J. A. (2001). Recurrent miscarriage and variant alleles of mannose binding lectin, tumour necrosis factor and lymphotoxin alpha genes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 126, 529–534 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01663.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry C. W., Brambati B., Eskes T. K., Exalto N., Fox H., Geraedts J. P., Gerhard I., Gonzales Gomes F., Grudzinskas J. G., Hustin J. (1995). The Euro-Team Early Pregnancy (ETEP) protocol for recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 10, 1516–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun H., Saftlas A. F. (2005). Association of human leucocyte antigen sharing with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Tissue Antigens 65, 123–135 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00367.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianca S., Barrano B., Cutuli N., Indaco L., Cataliotti A., Milana G., Barone C., Ettore G. (2010). No association between apolipoprotein E polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 93, 276. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova N., Horst J., Chlystun M., Croucher P. J., Nebel A., Bohring A., Todorova A., Schreiber S., Gerke V., Krawczak M., Markoff A. (2007). A common haplotype of the annexin A5 (ANXA5) gene promoter is associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 573–578 10.1093/hmg/ddm017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolor H., Mori T., Nishiyama S., Ito Y., Hosoba E., Inagaki H., Kogo H., Ohye T., Tsutsumi M., Kato T., Tong M., Nishizawa H., Pryor-Koishi K., Kitaoka E., Sawada T., Nishiyama Y., Udagawa Y., Kurahashi H. (2009). Mutations of the SYCP3 gene in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84, 14–20 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombell S., McGuire W. (2008). Cytokine polymorphisms in women with recurrent pregnancy loss: meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 48, 147–154 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottini E., Coromaldi L., Carapella E., Pascone R., Nicotra M., Coghi I., Lucarini N., Gloria-Bottini F. (1983). Intrauterine death: an approach to the analysis of genetic heterogeneity. J. Med. Genet. 20, 196–198 10.1136/jmg.20.3.196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahem S., Mehdi M., Landolsi H., Mougou S., Elghezal H., Saad A. (2011). Semen parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation as causes of recurrent pregnancy loss. Urology 78, 792–796 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch D. W., Gibson M., Silver R. M. (2010). Clinical practice. Recurrent miscarriage. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1740–1747 10.1056/NEJMcp1005330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker L., Farquharson R. G. (2002). Types of pregnancy loss in recurrent miscarriage: implications for research and clinical practice. Hum. Reprod. 17, 1345–1350 10.1093/humrep/17.5.1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz T., Lohse P., Kosian E., Thaler C. J. (2004). Vasoconstrictively acting AT1R A1166C and NOS3 4/5 polymorphisms in recurrent spontaneous abortions (RSA). Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 51, 323–328 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz T., Lohse P., Rogenhofer N., Kosian E., Pihusch R., Thaler C. J. (2003). Polymorphisms in the ACE and PAI-1 genes are associated with recurrent spontaneous miscarriages. Hum. Reprod. 18, 2473–2477 10.1093/humrep/deg474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecati M., Giannubilo S. R., Emanuelli M., Tranquilli A. L., Saccucci F. (2011). HLA-G and pregnancy adverse outcomes. Med. Hypotheses 76, 782–784 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazara O., Xiong S., Moffett A. (2011). Maternal KIR and fetal HLA-C: a fine balance. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 703–716 10.1189/jlb.0511227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chim S. S., Shing T. K., Hung E. C., Leung T. Y., Lau T. K., Chiu R. W., Lo Y. M. (2008). Detection and characterization of placental microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin. Chem. 54, 482–490 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. K., Choi B. C., Lee S. H., Kim J. W., Cha K. Y., Baek K. H. (2003). Expression of angiogenesis- and apoptosis-related genes in chorionic villi derived from recurrent pregnancy loss patients. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 66, 24–31 10.1002/mrd.10331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. K., Kwak-Kim J. (2008). Cytokine gene polymorphisms in recurrent spontaneous abortions: a comprehensive review. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 60, 91–110 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choufani S., Shapiro J. S., Susiarjo M., Butcher D. T., Grafodatskaya D., Lou Y., Ferreira J. C., Pinto D., Scherer S. W., Shaffer L. G., Coullin P., Caniggia I., Beyene J., Slim R., Bartolomei M. S., Weksberg R. (2011). A novel approach identifies new differentially methylated regions (DMRs) associated with imprinted genes. Genome Res. 21, 465–476 10.1101/gr.111922.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. B. (1996). A fresh look at the causes and treatments of recurrent miscarriage, especially its immunological aspects. Hum. Reprod. Update 2, 271–293 10.1093/humupd/2.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. B., Nybo Andersen A. M., Bosch E., Daya S., Delves P. J., Hviid T. V., Kutteh W. H., Laird S. M., Li T. C., van der Ven K. (2005). Evidence-based investigations and treatments of recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 83, 821–839 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. B., Pedersen B., Nielsen H. S., Nybo Andersen A. M. (2004). Impact of the sex of first child on the prognosis in secondary recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 19, 2946–2951 10.1093/humrep/deh516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. B., Riisom K., Lauritsen J. G., Grunnet N., Jersild C. (1989). Association of maternal HLA haplotypes with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Tissue Antigens 34, 190–199 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1989.tb01736.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. B., Ring M., Rosgaard A., Grunnet N., Gluud C. (1999). Association between HLA-DR1 and -DR3 antigens and unexplained repeated miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. Update 5, 249–255 10.1093/humupd/5.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. B., Steffensen R., Nielsen H. S., Varming K. (2008). Multifactorial etiology of recurrent miscarriage and its scientific and clinical implications. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 66, 257–267 10.1159/000149575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T., Handley D., Bunce K., Surti U., Hogge W. A., Peters D. G. (2011). Structural and regulatory characterization of the placental epigenome at its maternal interface. PLoS ONE 6, e14723. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci F., Boulenouar S., Kieckbusch J., Moffett A. (2011). How does variability of immune system genes affect placentation? Placenta 32, 539–545 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constancia M., Kelsey G., Reik W. (2004). Resourceful imprinting. Nature 432, 53–57 10.1038/432053a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulam C. B., Jeyendran R. S., Fishel L. A., Roussev R. (2006a). Multiple thrombophilic gene mutations rather than specific gene mutations are risk factors for recurrent miscarriage. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 55, 360–368 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulam C. B., Kay C., Jeyendran R. S. (2006b). Role of p53 codon 72 polymorphism in recurrent pregnancy loss. Reprod. Biomed. Online 12, 378–382 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61004-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan T. O., Trifa A., Farcas M., Militaru M., Netea M., Pop I., Popp R. (2011). The MTHFD1 c.1958 G > A polymorphism and recurrent spontaneous abortions. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 24, 189–192 10.3109/14767051003702794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupisti S., Fasching P. A., Ekici A. B., Strissel P. L., Loehberg C. R., Strick R., Engel J., Dittrich R., Beckmann M. W., Goecke T. W. (2009). Polymorphisms in estrogen metabolism and estrogen pathway genes and the risk of miscarriage. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 280, 395–400 10.1007/s00404-009-0927-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahabreh I. J., Jones A. V., Voulgarelis M., Giannouli S., Zoi C., Alafakis-Tzannatos C., Varla-Leftherioti M., Moutsopoulos H. M., Loukopoulos D., Fotiou S., Cross N. C., Zoi K. (2009). No evidence for increased prevalence of JAK2 V617F in women with a history of recurrent miscarriage. Br. J. Haematol. 144, 802–803 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher S., Shulzhenko N., Morgun A., Mattar R., Rampim G. F., Camano L., DeLima M. G. (2003). Associations between cytokine gene polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss. J. Reprod. Immunol. 58, 69–77 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00059-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendana M., Hizem S., Magddoud K., Messaoudi S., Zammiti W., Nouira M., Almawi W. Y., Mahjoub T. (2011). Common polymorphisms in the P-selectin gene in women with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Gene. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2011.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendana M., Messaoudi S., Hizem S., Jazia K. B., Almawi W. Y., Gris J. C., Mahjoub T. (2012). Endothelial protein C receptor 1651C/G polymorphism and soluble endothelial protein C receptor levels in women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 23, 30–34 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328349cae5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denschlag D., Marculescu R., Unfried G., Hefler L. A., Exner M., Hashemi A., Riener E. K., Keck C., Tempfer C. B., Wagner O. (2004). The size of a microsatellite polymorphism of the haem oxygenase 1 gene is associated with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 10, 211–214 10.1093/molehr/gah024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossenbach-Glaninger A., van Trotsenburg M., Helmer H., Oberkanins C., Hopmeier P. (2008). Association of the protein Z intron F G79A gene polymorphism with recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 90, 1155–1160 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudding T. E., Attia J. (2004). The association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and maternal factor V Leiden genotype: a meta-analysis. Thromb. Haemost. 91, 700–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler E. E., Flint J., Gibson G., Kong A., Leal S. M., Moore J. H., Nadeau J. H. (2010). Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 446–450 10.1038/nrg2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridi R. M., Agrawal S. (2011). Killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) and HLA-C allorecognition patterns implicative of dominant activation of natural killer cells contribute to recurrent miscarriages. Hum. Reprod. 26, 491–497 10.1093/humrep/deq341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridi R. M., Das V., Tripthi G., Talwar S., Parveen F., Agrawal S. (2009). Influence of activating and inhibitory killer immunoglobulin-like receptors on predisposition to recurrent miscarriages. Hum. Reprod. 24, 1758–1764 10.1093/humrep/dep217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatima N., Ahmed S. H., Salhan S., Rehman S. M., Kaur J., Owais M., Chauhan S. S. (2011). Study of methyl transferase (G9aMT) and methylated histone (H3-K9) expressions in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion (URSA) and normal early pregnancy. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 17, 693–701 10.1093/molehr/gar038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatini C., Gensini F., Battaglini B., Prisco D., Cellai A. P., Fedi S., Marcucci R., Brunelli T., Mello G., Parretti E., Pepe G., Abbate R. (2000). Angiotensin-converting enzyme DD genotype, angiotensin type 1 receptor CC genotype, and hyperhomocysteinemia increase first-trimester fetal-loss susceptibility. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 11, 657–662 10.1097/00001721-200010000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan R. R., Mustafa F. E., Al-Zaman I., Madan S., Issa A. A., Almawi W. Y. (2010). STAT3 polymorphisms linked with idiopathic recurrent miscarriages. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 22–27 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden A. L., Sferruzzi-Perri A. N., Coan P. M., Constancia M., Burton G. J. (2009). Placental efficiency and adaptation: endocrine regulation. J. Physiol. 587, 3459–3472 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franssen M. T., Musters A. M., van der Veen F., Repping S., Leschot N. J., Bossuyt P. M., Goddijn M., Korevaar J. C. (2011). Reproductive outcome after PGD in couples with recurrent miscarriage carrying a structural chromosome abnormality: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 17, 467–475 10.1093/humupd/dmr011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galazios G., Papazoglou D., Zografou C., Maltezos E., Liberis V. (2011). Alpha2B-adrenergic receptor insertion/deletion polymorphism in women with spontaneous recurrent abortions. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 37, 108–111 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt A., Scharf R. E., Mikat-Drozdzynski B., Krussel J. S., Bender H. G., Zotz R. B. (2005). The polymorphism of platelet membrane integrin alpha2beta1 (alpha2807TT) is associated with premature onset of fetal loss. Thromb. Haemost. 93, 124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloria-Bottini F., Nicotra M., Lucarini N., Borgiani P., La Torre M., Amante A., Gimelfarb A., Bottini E. (1996). Phosphotyrosine-protein-phosphatases and human reproduction: an association between low molecular weight acid phosphatase (ACP1) and spontaneous abortion. Dis. Markers 12, 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C., Goodman C. S., Hur J., Jeyendran R. S., Coulam C. (2009a). The association of Apoprotein E polymorphisms with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 61, 34–38 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C., Hur J., Goodman C. S., Jeyendran R. S., Coulam C. (2009b). Are polymorphisms in the ACE and PAI-1 genes associated with recurrent spontaneous miscarriages? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 62, 365–370 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C. S., Coulam C. B., Jeyendran R. S., Acosta V. A., Roussev R. (2006). Which thrombophilic gene mutations are risk factors for recurrent pregnancy loss? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 56, 230–236 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00419.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna C. W., Blair J. D., Stephenson M. D., Robinson W. P. (2011). Absence of SYCP3 mutations in women with recurrent miscarriage with at least one trisomic miscarriage. Reprod. Biomed. Online. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hefler L. A., Tempfer C. B., Bashford M. T., Unfried G., Zeillinger R., Schneeberger C., Koelbl H., Nagele F., Huber J. C. (2002). Polymorphisms of the angiotensinogen gene, the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene, and the interleukin-1beta gene promoter in women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 8, 95–100 10.1093/molehr/8.1.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser C. C., Eller A. G., Warren J., Branch D. W., Salmon J., Silver R. M. (2011). A case-control study of membrane cofactor protein mutations in two populations of patients with early pregnancy loss. J. Reprod. Immunol. 91, 71–75 10.1016/j.jri.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiby S. E., Apps R., Sharkey A. M., Farrell L. E., Gardner L., Mulder A., Claas F. H., Walker J. J., Redman C. W., Morgan L., Tower C., Regan L., Moore G. E., Carrington M., Moffett A. (2010). Maternal activating KIRs protect against human reproductive failure mediated by fetal HLA-C2. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 4102–4110 10.1172/JCI43998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiby S. E., Regan L., Lo W., Farrell L., Carrington M., Moffett A. (2008). Association of maternal killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors and parental HLA-C genotypes with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 23, 972–976 10.1093/humrep/den011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen A., Taylor J. A., Wilcox A., Berkowitz G., Schachter B., Chaparro C., Bell D. A. (1996). Xenobiotic metabolism genes and the risk of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Epidemiology 7, 206–208 10.1097/00001648-199603000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogge W. A., Prosen T. L., Lanasa M. C., Huber H. A., Reeves M. F. (2007). Recurrent spontaneous abortion and skewed X-inactivation: is there an association? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 196, e381–386; discussion e386–e388. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohlagschwandtner M., Unfried G., Heinze G., Huber J. C., Nagele F., Tempfer C. (2003). Combined thrombophilic polymorphisms in women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Fertil. Steril. 79, 1141–1148 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04958-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Liu C. M., Qi L., He T. Z., Shi-Guo L., Hao C. J., Cui Y., Zhang N., Xia H. F., Ma X. (2011). Two common SNPs in pri-miR-125a alter the mature miRNA expression and associate with recurrent pregnancy loss in a Han-Chinese population. RNA Biol. 8, 861–872 10.4161/rna.8.5.16034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hviid T. V., Hylenius S., Lindhard A., Christiansen O. B. (2004). Association between human leukocyte antigen-G genotype and success of in vitro fertilization and pregnancy outcome. Tissue Antigens 64, 66–69 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iinuma Y., Sugiura-Ogasawara M., Makino A., Ozaki Y., Suzumori N., Suzumori K. (2002). Coagulation factor XII activity, but not an associated common genetic polymorphism (46C/T), is linked to recurrent miscarriage. Fertil. Steril. 77, 353–356 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02989-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov P. D., Komsa-Penkova R. S., Konova E. I., Tsvyatkovska T. M., Kovacheva K. S., Simeonova M. N., Tanchev S. Y. (2010). Polymorphism A1/A2 in the cell surface integrin subunit beta3 and disturbance of implantation and placentation in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 94, 2843–2845 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E., Farquharson R. G., Christiansen O. B., Exalto N. (2006). Evidence-based guidelines for the investigation and medical treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 21, 2216–2222 10.1093/humrep/del150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jivraj S., Rai R., Underwood J., Regan L. (2006). Genetic thrombophilic mutations among couples with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 21, 1161–1165 10.1093/humrep/dei466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaare M., Butzow R., Ulander V. M., Kaaja R., Aittomaki K., Painter J. N. (2009a). Study of p53 gene mutations and placental expression in recurrent miscarriage cases. Reprod. Biomed. Online 18, 430–435 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60105-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaare M., Gotz A., Ulander V. M., Ariansen S., Kaaja R., Suomalainen A., Aittomaki K. (2009b). Do mitochondrial mutations cause recurrent miscarriage? Mol. Hum. Reprod. 15, 295–300 10.1093/molehr/gap021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaare M., Ulander V. M., Painter J. N., Ahvenainen T., Kaaja R., Aittomaki K. (2007). Variations in the thrombomodulin and endothelial protein C receptor genes in couples with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 22, 864–868 10.1093/humrep/del436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamali-Sarvestani E., Zolghadri J., Gharesi-Fard B., Sarvari J. (2005). Cytokine gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to recurrent pregnancy loss in Iranian women. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 171–178 10.1016/j.jri.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai T., Fujii T., Keicho N., Tokunaga K., Yamashita T., Hyodo H., Miki A., Unno N., Kozuma S., Taketani Y. (2001). Polymorphism of human leukocyte antigen-E gene in the Japanese population with or without recurrent abortion. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 45, 168–173 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2001.450308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karhukorpi J., Laitinen T., Karttunen R. (2003). Searching for links between endotoxin exposure and pregnancy loss: CD14 polymorphism in idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 5, 346–350 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2003.00092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karvela M., Papadopoulou S., Tsaliki E., Konstantakou E., Hatzaki A., Florentin-Arar L., Lamnissou K. (2008a). Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms in recurrent spontaneous abortions. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 278, 349–352 10.1007/s00404-008-0577-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karvela M., Stefanakis N., Papadopoulou S., Tsitilou S. G., Tsilivakos V., Lamnissou K. (2008b). Evidence for association of the G1733A polymorphism of the androgen receptor gene with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Fertil. Steril. 90, e9–e12 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Gu B. H., Song S., Choi B. C., Cha D. H., Baek K. H. (2011). ITI-H4, as a biomarker in the serum of recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) patients. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 1430–1440 10.1039/c0mb00319k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N. K., Choi Y. K., Kang M. S., Choi D. H., Cha S. H., An M. O., Lee S., Jeung M., Ko J. J., Oh D. (2006a). Influence of combined methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and thymidylate synthase enhancer region (TSER) polymorphisms to plasma homocysteine levels in Korean patients with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Thromb. Res. 117, 653–658 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S., Kim M. S., Lee S. H., Choi B. C., Lim J. M., Cha K. Y., Baek K. H. (2006b). Proteomic analysis of recurrent spontaneous abortion: identification of an inadequately expressed set of proteins in human follicular fluid. Proteomics 6, 3445–3454 10.1002/pmic.200500933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolte A. M., Nielsen H. S., Moltke I., Degn B., Pedersen B., Sunde L., Nielsen F. C., Christiansen O. B. (2011). A genome-wide scan in affected sibling pairs with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage suggests genetic linkage. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 17, 379–385 10.1093/molehr/gar003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolte A. M., Steffensen R., Nielsen H. S., Hviid T. V., Christiansen O. B. (2010). Study of the structure and impact of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G-A, HLA-G-B, and HLA-G-DRB1 haplotypes in families with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Immunol. 71, 482–488 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevsky G., Gracia C. R., Berlin J. A., Sammel M. D., Barnhart K. T. (2004). Evaluation of the association between hereditary thrombophilias and recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 558–563 10.1001/archinte.164.5.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse C., Steffensen R., Varming K., Christiansen O. B. (2004). A study of HLA-DR and -DQ alleles in 588 patients and 562 controls confirms that HLA-DRB1*03 is associated with recurrent miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 19, 1215–1221 10.1093/humrep/deh200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanasa M. C., Hogge W. A. (2000). X chromosome defects as an etiology of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Semin. Reprod. Med. 18, 97–103 10.1055/s-2000-13480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. M., Cleal J. K., Hanson M. A. (2012). Review: placenta, evolution and lifelong health. Placenta 33, S28–S32 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litridis I., Kapnoulas N., Natisvili T., Agiannitopoulos K., Peraki O., Ntostis P., Pantos K., Lamnissou K. (2011). Genetic variation in the CYP17 gene and recurrent spontaneous abortions. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 283, 289–293 10.1007/s00404-009-1348-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S. S., Ishibashi O., Ishikawa G., Ishikawa T., Katayama A., Mishima T., Takizawa T., Shigihara T., Goto T., Izumi A., Ohkuchi A., Matsubara S., Takeshita T. (2009). Human villous trophoblasts express and secrete placenta-specific microRNAs into maternal circulation via exosomes. Biol. Reprod. 81, 717–729 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccani M. A., Avissar-Whiting M., Banister C. E., McGonnigal B., Padbury J. F., Marsit C. J. (2010). Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with downregulation of miR-16, miR-21, and miR-146a in the placenta. Epigenetics 5, 583–589 10.4161/epi.5.7.12762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccani M. A., Marsit C. J. (2009). Epigenetics in the placenta. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 62, 78–89 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00716.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannik J., Vaas P., Rull K., Teesalu P., Rebane T., Laan M. (2010). Differential expression profile of growth hormone/chorionic somatomammotropin genes in placenta of small- and large-for-gestational-age newborns. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 2433–2442 10.1210/jc.2010-0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini S., Ticconi C., Gravina P., Tomassini M., Pietropolli A., Forte V., Federici G., Piccione E., Bernardini S. (2009). Thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 92, 694–702 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan R. I., O’Bryan M. K. (2010). Clinical review: state of the art for genetic testing of infertile men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 1013–1024 10.1210/jc.2009-1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menasha J., Levy B., Hirschhorn K., Kardon N. B. (2005). Incidence and spectrum of chromosome abnormalities in spontaneous abortions: new insights from a 12-year study. Genet. Med. 7, 251–263 10.1097/01.GIM.0000160075.96707.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi S., Al-Khateeb G. M., Dendana M., Sater M. S., Jazia K. B., Nouira M., Almawi W. Y., Mahjoub T. (2011). Genetic variations in the interleukin-21 gene and the risk of recurrent idiopathic spontaneous miscarriage. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 22, 123–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K., Miura S., Yamasaki K., Higashijima A., Kinoshita A., Yoshiura K., Masuzaki H. (2010). Identification of pregnancy-associated microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin. Chem. 56, 1767–1771 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamura H., Nishizawa H., Ota S., Suzuki M., Inagaki A., Egusa H., Nishiyama S., Kato T., Pryor-Koishi K., Nakanishi I., Fujita T., Imayoshi Y., Markoff A., Yanagihara I., Udagawa Y., Kurahashi H. (2011). Polymorphisms in the annexin A5 gene promoter in Japanese women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 17, 447–452 10.1093/molehr/gar008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani E., Suzumori N., Ozaki Y., Oseto K., Yamada-Namikawa C., Nakanishi M., Sugiura-Ogasawara M. (2011). SYCP3 mutation may not be associated with recurrent miscarriage caused by aneuploidy. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1259–1266 10.1093/humrep/der035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghraby J. S., Tamim H., Anacan V., Al Khalaf H., Moghraby S. A. (2010). HLA sharing among couples appears unrelated to idiopathic recurrent fetal loss in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Reprod. 25, 1900–1905 10.1093/humrep/deq154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G. E., Oakey R. (2011). The role of imprinted genes in humans. Genome Biol. 12, 106. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosaad Y. M., Abdel-Dayem Y., El-Deek B. S., El-Sherbini S. M. (2011). Association between HLA-E *0101 homozygosity and recurrent miscarriage in Egyptian women. Scand. J. Immunol. 74, 205–209 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musters A. M., Taminiau-Bloem E. F., van den Boogaard E., van der Veen F., Goddijn M. (2011). Supportive care for women with unexplained recurrent miscarriage: patients’ perspectives. Hum. Reprod. 26, 873–877 10.1093/humrep/der021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeimi S., Ghiam A. F., Mojtahedi Z., Dehaghani A. S., Amani D., Ghaderi A. (2006). Interleukin-18 gene promoter polymorphisms and recurrent spontaneous abortion. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 128, 5–9 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagirnaja L., Kasak L., Palta P., Rull K., Christiansen O. B., Esko T., Remm M., Metspalu A., Laan M. (2011). Role of DNA copy number variations in genetic predisposition to recurrent pregnancy loss. J. Reprod. Immunol. 90, 145. 10.1016/j.jri.2011.06.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagirnaja L., Rull K., Uuskula L., Hallast P., Grigorova M., Laan M. (2010). Genomics and genetics of gonadotropin beta-subunit genes: unique FSHB and duplicated LHB/CGB loci. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 329, 4–16 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelen W. L., Blom H. J., Steegers E. A., den Heijer M., Eskes T. K. (2000). Hyperhomocysteinemia and recurrent early pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 74, 1196–1199 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01595-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen E. C., van Montfoort A. P., Dumoulin J. C., Evers J. L. (2011). Epigenetics and the placenta. Hum. Reprod. Update 17, 397–417 10.1093/humupd/dmq052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbern D., Freemark M. (2011). Placental hormones and the control of maternal metabolism and fetal growth. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 18, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra M., Bottini N., Grasso M., Gimelfarb A., Lucarini N., Cosmi E., Bottini E. (1998). Adenosine deaminase and human reproduction: a comparative study of fertile women and women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 39, 266–270 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra M., Lucarini N., Battista C., Discepoli L., Coghi I. M., Bottini E. (1982). Genetic polymorphisms and human reproduction: a study of phosphoglucomutase in spontaneous abortion. Int. J. Fertil. 27, 229–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H. S. (2011). Secondary recurrent miscarriage and H-Y immunity. Hum. Reprod. Update 17, 558–574 10.1093/humupd/dmr005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguer-Dance M., Abu-Amero S., Al-Khtib M., Lefevre A., Coullin P., Moore G. E., Cavaille J. (2010). The primate-specific microRNA gene cluster (C19MC) is imprinted in the placenta. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 3566–3582 10.1093/hmg/ddq272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic B., Yuen R. K., Gordon L., Penaherrera M. S., Sharkey A., Moffett A., Craig J. M., Robinson W. P., Saffery R. (2011). Evidence for widespread changes in promoter methylation profile in human placenta in response to increasing gestational age and environmental/stochastic factors. BMC Genomics 12, 529. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybo Andersen A. M., Wohlfahrt J., Christens P., Olsen J., Melbye M. (2000). Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ 320, 1708–1712 10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober C., Aldrich C. L., Chervoneva I., Billstrand C., Rahimov F., Gray H. L., Hyslop T. (2003). Variation in the HLA-G promoter region influences miscarriage rates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1425–1435 10.1086/375501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara M., Aoki K., Okada S., Suzumori K. (2000). Embryonic karyotype of abortuses in relation to the number of previous miscarriages. Fertil. Steril. 73, 300–304 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00495-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostojic S., Pereza N., Volk M., Kapovic M., Peterlin B. (2008). Genetic predisposition to idiopathic recurrent spontaneous abortion: contribution of genetic variations in IGF-2 and H19 imprinted genes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 60, 111–117 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostojic S., Volk M., Medica I., Kapovic M., Meden-Vrtovec H., Peterlin B. (2007). Polymorphisms in the interleukin-12/18 genes and recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 58, 403–408 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou D., Galazios G., Papatheodorou K., Liberis V., Papanas N., Maltezos E., Maroulis G. B. (2005). Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms and idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 83, 959–963 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen F., Faridi R. M., Alam S., Agrawal S. (2011a). Genetic analysis of eNOS gene polymorphisms in association with recurrent miscarriage among North Indian women. Reprod. Biomed. Online 23, 124–131 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen F., Faridi R. M., Singh B., Agrawal S. (2011b). Analysis of CCR5 and CX3CR1 gene polymorphisms in association with unexplained recurrent miscarriages among north Indian women. Cytokine 56, 239–244 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen F., Faridi R. M., Das V., Tripathi G., Agrawal S. (2010). Genetic association of phase I and phase II detoxification genes with recurrent miscarriages among North Indian women. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16, 207–214 10.1093/molehr/gap096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen F., Tripathi G., Singh B., Agrawal S. (2009a). Association of chemokines receptor (CCR5 Delta32) in idiopathic recurrent miscarriages among north Indians. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 280, 229–234 10.1007/s00404-008-0901-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen F., Tripathi G., Singh B., Faridi R. M., Agrawal S. (2009b). Acetylcholinesterase gene polymorphism and recurrent pregnancy loss. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 106, 68–69 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier E., Bohec C., De Saint Martin L., Le Marechal C., Le Martelot M. T., Roche S., Laurent Y., Ferec C., Collet M., Mottier D. (2007). Strong evidence that skewed X-chromosome inactivation is not associated with recurrent pregnancy loss: an incident paired case control study. Hum. Reprod. 22, 2829–2833 10.1093/humrep/dem264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp T., Philipp K., Reiner A., Beer F., Kalousek D. K. (2003). Embryoscopic and cytogenetic analysis of 233 missed abortions: factors involved in the pathogenesis of developmental defects of early failed pregnancies. Hum. Reprod. 18, 1724–1732 10.1093/humrep/deg309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrowski D., Bettendorf H., Riener E. K., Keck C., Hefler L. A., Huber J. C., Tempfer C. (2005). Recurrent pregnancy failure is associated with a polymorphism in the p53 tumour suppressor gene. Hum. Reprod. 20, 848–851 10.1093/humrep/deh696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrowski D., Tempfer C., Bettendorf H., Burkle B., Nagele F., Unfried G., Keck C. (2003). Angiopoietin-2 polymorphism in women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Fertil. Steril. 80, 1026–1029 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihusch R., Buchholz T., Lohse P., Rubsamen H., Rogenhofer N., Hasbargen U., Hiller E., Thaler C. J. (2001). Thrombophilic gene mutations and recurrent spontaneous abortion: prothrombin mutation increases the risk in the first trimester. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 46, 124–131 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2001.460202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigoshin N., Tambutti M., Larriba J., Gogorza S., Testa R. (2004). Cytokine gene polymorphisms in recurrent pregnancy loss of unknown cause. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 52, 36–41 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai R., Regan L. (2006). Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet 368, 601–611 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69204-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajcan-Separovic E., Diego-Alvarez D., Robinson W. P., Tyson C., Qiao Y., Harvard C., Fawcett C., Kalousek D., Philipp T., Somerville M. J., Stephenson M. D. (2010). Identification of copy number variants in miscarriages from couples with idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum. Reprod. 25, 2913–2922 10.1093/humrep/deq202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren A., Wang J. (2006). Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and the risk of unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 86, 1716–1722 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey E., Kahn S. R., David M., Shrier I. (2003). Thrombophilic disorders and fetal loss: a meta-analysis. Lancet 361, 901–908 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12771-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N., Merikangas K. (1996). The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science 273, 1516–1517 10.1126/science.273.5281.1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger M. A., Betancourt M. T., Clark P., Lindqvist P. G., Dizon-Townson D., Said J., Seligsohn U., Carrier M., Salomon O., Greer I. A. (2010). The association of factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation and placenta-mediated pregnancy complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 7, e1000292. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rull K., Nagirnaja L., Ulander V. M., Kelgo P., Margus T., Kaare M., Aittomaki K., Laan M. (2008). Chorionic gonadotropin beta-gene variants are associated with recurrent miscarriage in two European populations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 4697–4706 10.1210/jc.2008-1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rull K., Tomberg K., Kõks S., Männik J., Möls M., Sirotkina M., Värv S., Laan M. (2012). TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand TRAIL as a potential biomarker for early pregnancy complications. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97. 10.1210/jc.2011-3192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo Y., Sata F., Yamada H., Konodo T., Kato E. H., Kataoka S., Shimada S., Morikawa M., Minakami H., Kishi R. (2004a). Interleukin-4 gene polymorphism is not involved in the risk of recurrent pregnancy loss. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 52, 143–146 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo Y., Sata F., Yamada H., Suzuki K., Sasaki S., Kondo T., Gong Y. Y., Kato E. H., Shimada S., Morikawa M., Minakami H., Kishi R. (2004b). Ah receptor, CYP1A1, CYP1A2 and CYP1B1 gene polymorphisms are not involved in the risk of recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 10, 729–733 10.1093/molehr/gah096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salker M., Teklenburg G., Molokhia M., Lavery S., Trew G., Aojanepong T., Mardon H. J., Lokugamage A. U., Rai R., Landles C., Roelen B. A., Quenby S., Kuijk E. W., Kavelaars A., Heijnen C. J., Regan L., Macklon N. S., Brosens J. J. (2010). Natural selection of human embryos: impaired decidualization of endometrium disables embryo-maternal interactions and causes recurrent pregnancy loss. PLoS ONE 5, e10287. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangha K. K., Stephenson M. D., Brown C. J., Robinson W. P. (1999). Extremely skewed X-chromosome inactivation is increased in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 65, 913–917 10.1086/302552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata F., Yamada H., Kondo T., Gong Y., Tozaki S., Kobashi G., Kato E. H., Fujimoto S., Kishi R. (2003a). Glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms and the risk of recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 9, 165–169 10.1093/molehr/gag021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata F., Yamada H., Yamada A., Kato E. H., Kataoka S., Saijo Y., Kondo T., Tamaki J., Minakami H., Kishi R. (2003b). A polymorphism in the CYP17 gene relates to the risk of recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 9, 725–728 10.1093/molehr/gag021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sata F., Yamada H., Suzuki K., Saijo Y., Kato E. H., Morikawa M., Minakami H., Kishi R. (2005). Caffeine intake, CYP1A2 polymorphism and the risk of recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 11, 357–360 10.1093/molehr/gah175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholer N., Langer C., Kuchenbauer F. (2011). Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers – true blood? Genome Med 3, 72. 10.1186/gm288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedhassani S. M., Houshmand M., Kalantar S. M., Modabber G., Aflatoonian A. (2010). No mitochondrial DNA deletions but more D-loop point mutations in repeated pregnancy loss. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 27, 641–648 10.1007/s10815-010-9435-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver R. M., Zhao Y., Spong C. Y., Sibai B., Wendel G., Jr., Wenstrom K., Samuels P., Caritis S. N., Sorokin Y., Miodovnik M., O’Sullivan M. J., Conway D., Wapner R. J. (2010). Prothrombin gene G20210A mutation and obstetric complications. Obstet. Gynecol. 115, 14–20 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c88918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K., Nair R. R., Khanna A. (2012). Functional SNP -1562C/T in the promoter region of MMP9 and recurrent early pregnancy loss. Reprod. Biomed. Online 24, 61–65 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriadis A., Makrigiannakis A., Stefos T., Paraskevaidis E., Kalantaridou S. N. (2007). Fibrinolytic defects and recurrent miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 109, 1146–1155 10.1097/01.AOG.0000260873.94196.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck T., van der Ven K., Kwak J., Beer A., Ober C. (1995). HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 haplotypes in aborted fetuses and couples with recurrent spontaneous abortion. J. Reprod. Immunol. 29, 95–104 10.1016/0165-0378(95)00937-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen R., Christiansen O. B., Bennett E. P., Jersild C. (1998). HLA-E polymorphism in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Tissue Antigens 52, 569–572 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb03088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]