Abstract

Objective

To assess a question–answer pair (QAP) database integrated with websites developed for drug information centres to answer complex questions effectively.

Design

Descriptive study with comparison of two subsequent 6-year periods (1995–2000 and 2001–2006).

Setting

The Regional Medicines Information and Pharmacovigilance Centres in Norway (RELIS).

Participants

A randomised sample of QAPs from the RELIS database.

Primary outcome measure

Answer time in days compared with Mann–Whitney U test.

Secondary outcome measure

Number of drugs involved (one, two, three or more), complexity (judgemental and/or patient-related or not) and literature search (none, simple or advanced) compared with χ2 tests.

Results

842 QAPs (312 from 1995 to 2000 and 530 from 2001 to 2006) were compared. The fraction of judgemental and patient-related questions increased (66%–75% and 54%–72%, respectively, p<0.01). Number of drugs and literature search (>50% advanced) was similar in the two periods, but the fraction of answers referring to the RELIS database increased (13%–31%, p<0.01). Median answer time was reduced from 2 days to 1 (p<0.01), although the fraction of complex questions increased from the first to the second period. Furthermore, the mean number of questions per employee per year increased from 66 to 89 from the first to the second period.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that RELIS has a potential to efficiently answer complex questions. The model is of relevance for organisation of drug information centres.

Article summary

Article focus

A model with a national network of drug information centres in Norway (RELIS) with a common QAP database integrated with websites has been developed.

This article describes how the model makes it possible to effectively answer complex questions.

Key messages

A randomised sample of QAPs from two subsequent 6-year periods after RELIS started in 1995 were analysed retrospectively.

Comparison of the second to the first period shows RELIS' potential to answer complex questions with reduced answer time and more frequent use of previous answers in the database.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A randomised sample from the two periods was analysed.

The study is descriptive, and analysis is retrospective with poorly defined variables.

Development of RELIS (personnel and technology) as well as the internet during the total study period suggests that interpretation of the results should be performed with caution.

Introduction

The regional medicines information and pharmacovigilance centres (RELIS) were established in 1995 with two regional centres. Two additional centres were started in 1997 and 1998 with a fifth added in 2001. Today, RELIS is a national network made up of four (two centres in Oslo became one in 2010) drug information centres (DICs). They are localised at regional university hospitals in Norway, where pharmacists and clinical pharmacologists answer questions from healthcare professionals. In 1995, RELIS started developing a full-text question–answer pair (QAP) database through cooperation with a software company (Arnett AS, Bergen, Norway). The database was originally an internal (not public) Microsoft Access application but was converted to a web-based SQL database with separate public (through the RELIS homepage) and internal (through the RELIS intranet) interfaces in 2000–2001. QAPs are indexed and published by the staff to be searchable in Norwegian for healthcare professionals free of charge through the public interface. QAPs unsuitable for the public domain (eg, questions answered solely by a copy of a previous answer, questions which lack public interest and not associated with drugs or questions that contain information that could identify a patient through description of a rare disease) are allocated to the internal interface (RELIS internal database) only.

QAPs have been retrieved from the database through a simple or advanced search function since 1995. Today, the RELIS public database by default contains a simple search function where a drug or text word (eg, hypertension) is entered, but a more advanced search function with Boolean operators (AND/OR/NOT), categories (eg, interactions, pregnancy), text word, individual centre with question number is an option. In the internal interface, the advanced search function is default. The result of a search (eg, loratadine AND pregnancy) is presented as a report of QAPs organised chronologically (the newest on top). An individual QAP in the report could contain a previous answer (in the RELIS public database) as a linked reference available in full text.

The websites include the RELIS homepage (http://www.relis.no) targeted at healthcare professionals and the RELIS intranet available for RELIS only. The websites were developed in 2000, updated in 2010 and represent the public and internal domain of the RELIS network, respectively. On the homepage, RELIS publish relevant drug information including relevant QAPs from the database, announce meetings, present recent publications and describe news from the pharmacovigilance work. Importantly, healthcare professionals can register for a monthly newsletter (email) with selected drug information from the homepage. The intranet functions as a medium for all activity and cooperation between the centres in Norway. Thus, it contains important documents, training and quality guidelines, discussions and information to all employees. In addition it includes dedicated sections for individual centres, common working groups and projects.

In 1995 and up to 2006, the majority of questions to RELIS were communicated through telephone followed by email. However, in the last years, questions have been mainly submitted through a web question form available on the homepage. Healthcare professionals register demographic data (occupation and working address), the question (the patient being made anonymous) and a deadline for the answer (answer time). Demographic data are used for distribution of questions to the respective centres, but all information in the web question form are shared by all RELIS staff, regardless of location, through exclusive emails. Other questions (through telephone, fax, letters or ordinary email) not submitted through the web-based question form have still been shared by all staff since 1995 through an ‘answer in progress’ functionality in the RELIS internal database. The name of the employee who received the question and the one handling it is also registered. In the case of particularly complex questions involving several authors, co-signatures are used. In this way, the handling of a question is fully traceable and answers to subsequent similar questions can be based on re-use of QAPs and communication with the authors.

Physicians consider the information provided by RELIS in general and on drug use in pregnancy in particular to be of high quality and of significant clinical impact.1–3 Questions to the centres are mainly about psychoactive drugs and adverse effects similar to other DICs.4 5 Less is known about complexity of questions and how this influences answer time. In the present study, we retrospectively analysed a randomised sample of QAPs in two time periods after RELIS started. The objective was to examine if this model for DICs has a potential to answer complex questions effectively.

Methods

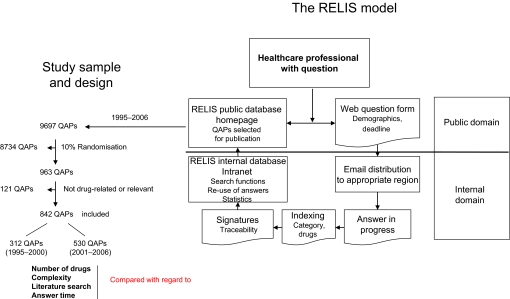

Contents of the RELIS database were analysed to illustrate how questions were answered. Two periods of 6 years were compared (1995–2000 and 2001–2006). QAPs published in the public database in the respective periods were used. They reflect the process of answering better than QAPs unsuited for publication as described above. Overall publication frequency in the period (1995–2006) was 80% (range 66%–95% between individual centres). Relevant data from QAPs, including question number, were transferred to SPSS V.17.0 (SPSS Inc.) for analysis and subjected to a randomisation procedure in the application. From a total of 9697 QAPs, a randomised sample of 963 QAPs was used for further analysis. Each QAP was compared with the information in the associated paper version (all documents and information on answering the question) saved in the respective RELIS centre. The paper version contained the day the question was received and the corresponding day an answer was provided. One hundred and twenty-one QAPs were excluded because the questions concerned nutritional or herbal medicine (n=65), non-medical products from pharmacies, homeopathy, medical equipment, disinfection or chemicals (n=26), or questions that were answered solely by a previous answer or by sending copies of relevant scientific articles (n=30). Exclusion of these QAPs was based on the notion that DICs primary function and resources (personnel and available drug information sources) are directed to answer questions concerning drugs. Thus, based on a sequence of selection criteria (publication or not, randomisation to 10% and the final exclusion), 842 QAPs were included in the study. They were analysed for the number of drugs involved in the question, complexity, the type of literature search performed, use of references (the number of references used and/or use of the RELIS database as a reference) and the time needed for providing an answer (in days). The number of drugs involved in the queries were categorised as one, two or three or more. Questions concerning groups of drugs, for example, antipsychotics, were categorised as three or more drugs. Judgemental and/or patient-related questions were defined as complex. Factual questions, such as the therapeutic dose of a drug or its half-life, can easily be located in textbooks, monographs or databases. Judgemental questions require by definition the integration of data or knowledge and experience in the process of making a decision regarding a specific therapeutic problem.6 The original definition assumed that answers to judgemental questions could not be given in any single reference source, but this assumption has been excluded in the present and other studies.7 Judgemental questions are frequently patient-related because they involve drug information applied to a clinical situation associated with patient-specific characteristics. They can, however, also represent a more general drug-related problem. If the question was answered without searching the literature and without consulting colleagues, the literature search was categorised as none. If it was necessary to search the RELIS database, databases containing monographs like the Micromedex, the Summary of Product Characteristics for the drug, reference books and/or colleagues/other health professionals only, the search was categorised as simple. If searches in databases like Medline, Embase or Cochrane to obtain original articles were necessary, the search was categorised as advanced. The number of questions received each year were analysed by use of the statistical function in the database. This function allows RELIS to quantify the activity in the centres (eg, the number of questions from physicians or pharmacists from a particular county from a particular time period to a particular RELIS can be retrieved). The number of employees in the centres in the respective periods was estimated but did not include all cases of maternity leave, leave of absence and vacant positions. The mean number of questions per employee per year was calculated from data corresponding to the start (year) and end (year) of each period. Figure 1 summarises the present RELIS model together with the study sample and design.

Figure 1.

Healthcare professionals with questions can search the Regional Medicines Information and Pharmacovigilance Centres (RELIS) public database or submit a web question form through the RELIS homepage. The questions with deadline and demographics are distributed to all RELIS staff, who have access to the question–answer pairs (QAPs) throughout their processing in the RELIS internal domain. All QAPs are stored in the RELIS internal database and selected for publication in the RELIS public database. A randomised sample of QAPs from 1995–2000 to 2001–2006 were retrospectively analysed and compared with regard to number of drugs involved (one, two, three or more), complexity (judgemental and/or patient-related or not), literature search (none, simple or advanced) and answer time (in days).

Statistics

The data were analysed using SPSS V.17.0 (SPSS Inc). Proportions between groups were analysed using χ2 comparisons. Discrete data between groups were analysed using Mann–Whitney U test. p Values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of a randomised sample of 842 QAPs from 1995 to 2000 (n=312) and 2001–2006 (n=530), respectively, from the RELIS public database. The mean number of questions per employee per year increased from 66 to 89 from the first to the second period.

Table 1.

Characteristics of a randomised sample of 842 question–answer pairs in the RELIS public database 1995–2006

| Period | 1995–2000 | 2001–2006 | p Value |

| Questions, n | 312 | 530 | |

| Drugs involved, category: % | One: 49 | One: 45 | 0.434§ |

| Two: 19 | Two: 22 | ||

| Three or more: 32 | Three or more: 34* | ||

| Judgemental questions, n (%) | 207 (66) | 399 (75) | 0.005§ |

| Patient-related questions, n (%) | 170 (54) | 379 (72) | <0.001§ |

| Answers, n | 312 | 530 | |

| Literature search, type: %† | None: 3 | None: 2 | 0.315§ |

| Simple: 43 | Simple: 40 | ||

| Advanced: 54 | Advanced: 58 | ||

| Reference to RELIS database, n (%) | 39 (13) | 164 (31) | <0.001§ |

| References, median (average) | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 0.100¶ |

| Days, median (average)‡ | 2 (8.4) | 1 (5.0) | 0.001¶ |

The total number exceeds 100% because of rounding off to the nearest whole number.

Simple literature search included monographs (eg, Martindale, Summary of Product Characteristics), advanced literature search included articles (eg, databases like Medline and Embase).

Answer time is influenced by some extreme outliers (>100 days) and choice of deadline for answer (‘not important’ is an option).

χ2 Test for contingency tables.

Mann–Whitney U test for two independent samples.

Discussion

This paper describes a QAP database integrated with websites for RELIS in Norway. The model is characterised by a traceable answering process of questions submitted to the centres, which are stored in full text in a searchable database. Continuous growth of the database makes it a valuable source of drug information for healthcare professionals. Our analysis of two periods after RELIS started demonstrates the potential of the database to be an effective reference source through re-use of previous answers. Furthermore, RELIS represents a model for DICs where the staff efficiently answers complex questions through cooperation in a network.

The RELIS model includes quality standards and in-house training which ensures that the process of answering questions is similar across the centres. The intranet contains several guidelines on how to handle QAPs (eg, how to write references, how to index in the database). Furthermore, each centre uses the same commercial drug information databases and textbooks as sources. How to answer a question is discussed within each RELIS by informal discussions or use of co-signature. It is also discussed between different centres due to the transparency and traceability of the model and regularly in the annual national meetings where all centres participate. Thus, a person trained and located in one centre can do work for a different centre through this model in case of shortage of staff or increased workload in one of the regions. In this way, the individual centres are effective backups for each other. The ‘answer in progress’ function facilitates communication about new questions. Similar questions submitted simultaneously or subsequently can be answered based on previous work and communication between individual centres. In this way, unnecessary double work can be reduced and complex questions asked frequently can be answered within a short time frame.

Our data show that the re-use of the RELIS database as a reference source in the answering of new questions was significantly higher in 2001–2006 than in 1995–2000. This is not surprising, as the number of available QAPs in the second time period was higher and the chance of finding relevant information increases with the number of questions received at RELIS. Re-use of the database as a source of information is expected to decrease the workload of repeated questions, but patient-specific characteristics of relevance to the answer process still has to be taken into account. Furthermore, complex questions not answered previously are associated with increased workload. This is illustrated by the finding that the average number of references in the QAPs did not decrease from the first to the second period and advanced search strategies were still used in most cases. We recently performed a prospective study where the extent of literature search was the individual factor best predicting the time spent answering questions in RELIS.8 However, in RELIS, repeated questions are subjected to a new literature search if 3 months have passed since a previous answer was provided, and this was more likely to happen in the period 1995–2006. With repeated questions today, a previous answer in the database is more likely to be updated and could be re-used. An illustrating example is the common question of antidepressants and pregnancy, which is usually patient-related and judgemental in its form. This type of question is frequently submitted to RELIS because information in product monographs is categorical and not useful for solving a clinical situation with a depressed pregnant patient in need of drug therapy. A recent answer from the database with updated literature search can be provided within much shorter time limits than would be expected.

Interestingly, the answer time has been reported to be the parameter associated with dissatisfaction with DICs among physicians. A DIC in Denmark reported a median time to answer (final answer in contrast to preliminary answer) of 25 days among satisfied physicians and 56 days among unsatisfied physicians.9 In our material, the median time before a written answer was submitted to the questioner was 2 days and 1 day in the periods 1995–2000 and 2001–2006, respectively. In the subgroup of judgemental and patient-related QAPs, the corresponding reduction was 4 to 2 days, and 2 to 1 day, respectively (data not shown). The average number of days before a written answer was given was reduced from 8 to 5 days in the two periods. These figures are influenced by a few extreme outliers (>100 days before an answer were documented as given). Furthermore, ‘not important’ is an option when healthcare professionals specify their deadline for the answer. Some questions are dependent on documentation from external sources (eg, pharmaceutical industry) not controlled by RELIS. Thus, the median number of days before an answer is given is probably more representative for the service than the average. However, the answer time depends greatly on how fast the questioner needs his answer and how many other questions that are received in the same time period. Increased staffing could also influence answer time. However, our calculation of the mean number of questions per employee per year does not account for all the increase in activity during the period after RELIS started. Several questions answered by telephone were not documented in the database, and in 2003, the centres increased the number of employees mainly to handle adverse drug reaction reports due to new tasks in pharmacovigilance. In the prospective study, we measured the time spent to answer each of 96 questions.8 The mean time needed to provide an answer was 4.0 h, whereas the median time was 3.0 h (range 0.5–24 work hours). This represents effective time, not the number of workdays (including other work and lunch) recorded in the present material. Interestingly, in the same study we also observed a minor impact of the number of drugs on answer time. This could be due to the experience that questions about drug interactions are managed effectively by use of drug interaction software.8

The number of patient-related questions was significantly higher in the second time period than in the first one, as were the number of judgemental questions. These two variables are related to each other in such a way that patient-related questions often are associated with judgemental considerations and vice versa. In the present study, they were used to indicate complex questions. In an earlier study, we found that more than 60% of the queries were judgemental and most of the queries were patient-related.8 The sample in that study was much smaller compared with the present results, but the numbers corresponds well. However, the assessment of judgemental/non-judgemental is quite subjective, and others have used the term consultative for questions that requires clinical advice on a special case. Consultative questions usually entail discussion with the inquirer on possible benefits and hazards of one or more courses of action in a clinical case.10 The justification for using judgemental classification versus consultative and other classifications is not clear-cut, and this makes comparisons between different studies difficult. However, DICs in Norway are similar to the Swedish, which have reported a particularly high proportion of consultative queries.11 During the history of RELIS, the number of questions from physicians has steadily increased in proportion to other groups of healthcare professionals. In 2011, 65% of 2565 questions came from physicians (40% of physicians from general practice), while 84% were patient-related.

Adverse effects and pregnancy represent the two most common categories of questions to RELIS and are a substantial part of the QAP database. Feedback to healthcare professionals who submit adverse drug reaction reports commonly involve use of this database. Furthermore, several reports were originally generated by a question by a physician concerning possible adverse effects. Thus, the database and the websites are strongly integrated with the pharmacovigilance work. Our answers have been evaluated to be of high quality and of significant clinical impact in several studies.1–3 These studies cover the period of 1995–1998 and 2006. Interestingly, the study from 2006 concerned drug information in pregnancy, which represents a category of questions where re-use of information in the database is particularly frequent.3 However, such evaluations are performed by a selected group of physicians and cannot be generalised to other healthcare professionals. Although consequences on a patient level are usually not known in these results, a particularly relevant finding was that almost 10% of physicians who evaluated the service reported that the information prevented unnecessary termination of a pregnancy.3

The present model could be of international interest for existing or planned network of DICs. A recent survey of 75 DICs in the USA found an increase in the number of complex questions in 70%, while 53% reported an increase in the time required to answer each question.12 A shared database represents a useful tool for uniform handling and documentation of complex questions. Furthermore, it becomes an increasingly important drug information source for healthcare professionals as well as employees in the network. Through a solution with web-based communication, the model could be of particular importance in poor and undeveloped countries and continents with frequent epidemics, outbreaks and health problems where rapid dissemination of drug information is essential.

Conclusions

We conclude that RELIS represents a model with a potential to efficiently answer complex questions. The model is of relevance for organisation of DICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all RELIS staff (past and present) who contributed to development of this model from 1995 to the present by providing drug information to healthcare professionals.

Footnotes

To cite: Schjøtt J, Reppe LA, Roland P-DH, et al. A question–answer pair (QAP) database integrated with websites to answer complex questions submitted to the Regional Medicines Information and Pharmacovigilance Centres in Norway (RELIS): a descriptive study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000642. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000642

Contributors: JS planned the manuscript and wrote it. LAR collected and analysed the material from the RELIS database. PDHR provided historical and technical data on the RELIS model. TW and JS designed the figure. JS designed the table. All authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and discussed drafts towards approval of the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All QAPs used in this study were obtained from the public RELIS database, which is searchable in Norwegian for healthcare professionals free of charge. QAPs from the database were compared with the information in the associated paper version (all documents and information on handling of the question) saved in archives in the respective RELIS centre.

References

- 1.Schjøtt J, Pomp E, Gedde-Dahl A, et al. What do health professionals ask RELIS Vest service and how satisfied are they with the answers? (In Norwegian). J Norw Med Assoc 2000;120:204–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schjøtt J, Pomp E, Gedde-Dahl A. Quality and impact of problem-oriented drug information: a method to change clinical practice among physicians? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2002;57:897–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost Widnes SK, Schjøtt J. Drug use in pregnancy-physicians' evaluation of quality and clinical impact of drug information centres. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:303–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Öhman B, Lyrvall H, Törnqvist E, et al. Clinical pharmacology and the provision of drug information. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1992;42:563–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troger U, Meyer FP. The regional drug-therapy consultation service centre-a conception that has been serving patients and physicians alike for 30 years in Magdeburg (Germany). Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000;55:707–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grace M, Wertheimer AI. Judgmental questions processed by a drug information center. Am J Hosp Pharm 1975;32:903–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merritt GJ, Garnett WR, Eckel FM. Analysis of a hospital-based information center. Am J Hosp Pharm 1977;34:42–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reppe LA, Spigset O, Schjøtt J. Which factors predict the time spent answering queries to a drug information centre? Pharm World Sci 2010;32:799–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedegaard U, Damkier P. Problem-oriented drug information: physicians' expectations and impact on clinical practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:515–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies DM, Ashton CH, Rao JG, et al. Comprehensive clinical drug information service: first year's experience. Br Med J 1977;1:89–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llerena A, Öhman B, Alván G. References used in a drug information centre. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1995;49:87–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg JM, Schilit S, Nathan JP, et al. Update on the status of 89 drug information centers in the United States. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009;66:1718–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.