Abstract

Targeted gene delivery offers immense potential for clinical applications. Liposomes decorated with targeting ligands have been extensively used for both in vitro and in vivo gene delivery. Lipoplexes with high cholesterol content that result in cholesterol domain formation within the complexes have been shown to exhibit enhanced transfection in vitro and resistance to serum-induced aggregation. In the present study, folate was employed as a targeting ligand that was conjugated with either cholesterol or a diacyl lipid (DSPE), and these conjugates were incorporated into lipoplexes formulated with DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69) that are known to possess cholesterol nanodomains. Cellular uptake and transfection of these lipoplexes in the presence of 50% serum were examined when the ligand is located within or excluded from the cholesterol nanodomain. Lipoplexes with folate-cholesterol exhibited a 50-fold increase in transfection as compared to those with folate-DSPE, while the cellular uptake level is only 40% of that with folate-DSPE. These results indicate that the presence of the ligand within the cholesterol domain promotes more productive transfection in cultured cells, and intracellular trafficking of the lipoplexes after entry into cells plays a crucial role in gene delivery.

Keywords: folate, nanodomain, gene delivery, liposome, cholesterol, serum-stable, transfection

Introduction

Cationic liposomes have been widely used for in vitro and in vivo gene delivery. However, serum has been reported to exert its inhibitory effect by binding serum proteins to cationic lipid/DNA complexes, which leads to structural reorganization, aggregation and/or dissociation of the complexes 1–4. Thus, it is of interest to develop delivery systems that can resist serum-induced aggregation and efficiently transfer genes in the presence of serum. Currently the predominant strategy is to utilize PEGylated components to sterically shield the delivery vehicles from blood components 5–7. This strategy has been utilized for decades in the development of liposome-based formulations and has been shown to increase circulation lifetimes and allow the accumulation of liposomes containing small molecule drugs in tumors 8. It is thought that PEGylated liposomes mediate steric stabilization, ultimately reducing surface-surface interaction including the aggregation of liposomes. Although the enhanced circulation time of PEGylated liposomes allows the accumulation of lipoplexes in tumors, the influence of PEGylation on cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking compromises the ultimate delivery efficiency 7, 9–11.

Studies have demonstrated that enhancement of “passive targeting” requires targeting ligands to be attached to the distal end of the PEGylated components such that the ligand is projected beyond the shielding of PEG, and thereby allow binding to receptors on the cell surface 12–14. Site specific delivery of lipoplexes requires the identification of cell surface receptors and the appropriate ligands for receptor-mediated endocytosis. The most popular approach is to use liposomes or polymers with specific ligands such as antibodies, transferrin, folic acid, RGD peptide, anisamide, etc 15–21. More specifically, folate receptors are frequently overexpressed in solid tumor and myeloid leukemias 22, 23, while most normal tissues lack expression of folate receptors. Therefore folic acid has been used for targeting liposomal drug delivery to tumors that overexpress the folate receptor 24–26.

Previous studies 4, 27 have shown lipoplexes with high levels of cholesterol exhibited enhanced transfection in vitro and resistance to serum-induced aggregation. Furthermore, cholesterol nanodomain formation was detected in lipoplexes with cholesterol contents above 52% (wt/wt). Considering that the cholesterol domain is neutral and separated from the positively charged lipid moiety that binds to anionic macromolecules (e.g., DNA, siRNA, serum proteins) it is potentially advantageous to utilize cholesterol domains as anchoring sites for ligands. In fact, our previous work has demonstrated that cholesterol domains do not bind detectable levels of protein27. We hypothesized that the spatial separation of the ligand from cationic lipids may alter uptake and/or trafficking; a phenomenon that is known to be affected by serum protein adsorption 28. Because the ability of the ligand to locate within the cholesterol nanodomain will depend upon its anchor, different conjugates can be prepared that allow the ligand to partition within, or be excluded from, the cholesterol domain. To assess the effects of ligand location on gene delivery, our study utilizes folate conjugated onto either cholesterol or a diacyl lipid (DSPE), and these conjugates are incorporated into lipoplexes that possess cholesterol nanodomains. More specifically, these experiments assess cell uptake and transfection when the ligand is located within or excluded from the cholesterol nanodomain. Our results indicate that the presence of the ligand within the cholesterol domains appears to facilitate transfection in cultured cells, though increased cellular uptake cannot explain our observations. These results suggest that intracellular trafficking of the lipoplexes after entry into cells plays a more crucial role in gene delivery, and that the presence of the ligand within the cholesterol nanodomain promotes more productive gene delivery into cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Luciferase plasmid DNA (5.9 kb) was generously provided by Valentis Inc. (Burlingame, CA). N-(1-(2, 3-dioleoyloxy) propyl)-N, N, N-trimethylammonium chloride (DOTAP), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) (NBD-DOPE), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG2000-DSPE) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[folate(polyethylene-glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000 Folate) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Synthetic cholesterol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Folate-PEG2000-Cholesterol was custom synthesized by GLS synthesis Inc. (Worcester, MA) as described by Zhao et al 29. The luciferase assay kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA) and was filtered with 0.22-μm low protein binding cellulose acetate filter from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) before use. All chemicals were of reagent grade or higher quality.

Liposome and lipoplex preparation

DOTAP combined with cholesterol was mixed in chloroform. The lipid mixture was dried under a stream of nitrogen gas and placed under vacuum (100 mTorr) for 2 hours to remove residual chloroform, and dried lipids were subsequently resuspended in autoclaved, distilled water and sonicated. Cationic liposomes were prepared immediately before use as previously described 4. Lipoplexes were prepared by mixing equal volumes of DNA (40 μg/ml) and liposomes (0.5 mM), and incubated at room temperature for 15 min before transfection.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Liposomes with different lipid conjugates were prepared for DSC measurements using a Microcal VP-DSC (Microcal Inc., Northampton, MA). Samples were heated from 10–90°C at the rate of 90°C/h, and the resulting DSC curves were analyzed by using the fitting program (DSC Origin 7.0) provided by Microcal Inc.

Dynamic light scattering and zeta potential analysis

Lipoplexes at charge ratio of 4:1 were diluted to a final volume of 500 μl with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Diluted samples were transferred to a cuvette for dynamic light scattering analysis on a Nicomp 380 Zeta Potential/Particle Sizer (Particle Sizing Systems, Santa Barbara, CA). Channel width was set automatically based on the rate of fluctuation of scattered light intensity and triplicate preparations were measured at room temperature for each formulation. Volume-weighted Gaussian size distribution was fit to the autocorrelation functions, and particle size values were obtained as previously described 30. Samples were then subjected to an electric field in a Nicomp 380 Zeta Potential/Particle Sizer for zeta potential determination.

In vitro transfection assay

KB cells (ATCC #CCL-17) that overexpress the folate receptor were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 units/ml penicillin G and 50μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. For in vitro transfection, cultures were freshly seeded at 3 × 105 cells/well in 12-well plates 24 hrs before transfection. Lipoplexes (40 μl) containing 0.8μg DNA were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and then transferred into wells containing freshly washed cells in 50% FBS medium. The cells were incubated with lipoplexes for 4 hrs before the medium was replaced with the medium containing 10% FBS. Forty hours after transfection, the culture medium was discarded, and the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed with 200 μl of lysis buffer (Promega). Twenty microliters of cell lysis solution was used to assay for luciferase expression via a luciferase assay kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The signal was quantified using a Monolight 2010 Luminometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Protein contents were determined with a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a THERMOmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Flow cytometry analysis of cellular uptake of lipoplexes

Lipoplexes (1.6 μg DNA) containing 1 mol% of NBD-DOPE as lipid fluorescent marker were incubated with 4×105 KB cells at 37°C for 4 hours. After incubation, cells were washed with ice cold PBS three times and collected by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min. The final cell pellets were resuspended by vortex mixing, and fixed in 1% formalin in PBS. To quench the bound lipoplexes on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, 0.1% Trypan blue solution was added into the final cell suspension. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted on a BD FACS calibur system (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) with the excitation at 488 nm and emission at 530 nm. Fifty thousand cells were analyzed for each sample and the mean fluorescence intensity was calculated by FlowJo software as the cellular uptake of lipoplexes.

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine statistical significance (p<0.05) among the mean values for transfection efficiency. A Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance (p<0.05) between formulations.

Results

Cholesterol domain formation by DSC

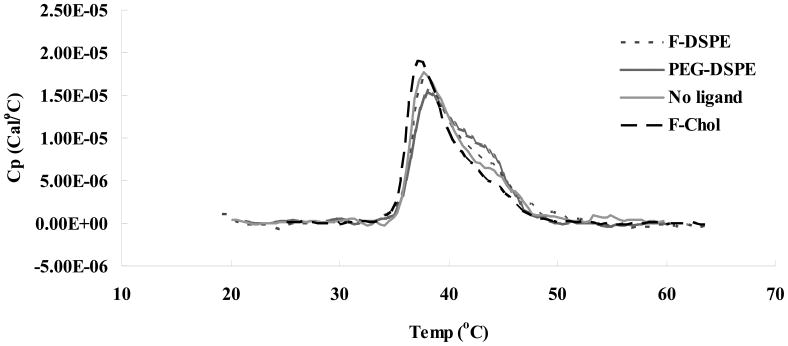

Our previous study 27 of the interaction between the cationic lipid DOTAP and cholesterol has shown that liposome preparation at high cholesterol content (≥ 52 wt %) results in the formation of a cholesterol domain within the delivery vehicle. Furthermore, we have established that domain formation is not altered by DNA binding to the DOTAP/cholesterol liposomes at different charge ratios. In the current study, liposomes targeting the folate receptor were prepared with DOTAP, cholesterol and folate-conjugate, and samples were subjected to thermal analysis. Cholesterol domain formation was detected on liposomes in the presence and absence of targeting ligand (Fig 1). In all the formulations with 80% cholesterol, transition of anhydrous cholesterol was clearly detected at 38°C, indicating that inclusion of the lipid conjugate, i.e. folate-cholesterol, folate-DSPE or PEG2000-DSPE does not significantly alter cholesterol domain formation.

Fig. 1.

DSC heating scan of liposomes formulated with DOTAP and 69% cholesterol with different ligand as indicated in the graph, scan rate = 90°C/h, 0.25 mM DOTAP in deionized, distilled water (ddH2O). F-DSPE: folate-DSPE; F-Chol: folate-cholesterol.

Particle size and zeta potential measurement

Particle size and zeta potential of lipoplexes containing 69% cholesterol and ligand conjugates were measured at charge ratio (+/−) of 4: 1 (Table I). It should be noted that the zeta potential of lipoplexes are comparably high at this charge ratio (≥ 30) and the particle sizes of all the formulations are 150–200 nm. These results indicate that the physical properties of the lipoplexes are not dramatically altered by the inclusion of the folate conjugates.

Table I.

Particle size and zeta potential of DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69) lipoplex at charge ratio of 4:1. Data represent mean ± one standard deviation of three replicates.

| Ligand | Particle diameter (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| No ligand | 165.8 ± 16.4 | +45.8 ± 5.1 |

| 0.4% Folate-cholesterol | 197.7 ± 16.8 | +34.0 ± 11.7 |

| 0.4% Folate-DSPE | 153 ± 8.8 | +30.3 ± 4.7 |

| 0.4% PEG-DSPE | 186.9 ± 2.1 | +37.2 ± 6.2 |

Effect of cholesterol domain on ligand-mediated transfection

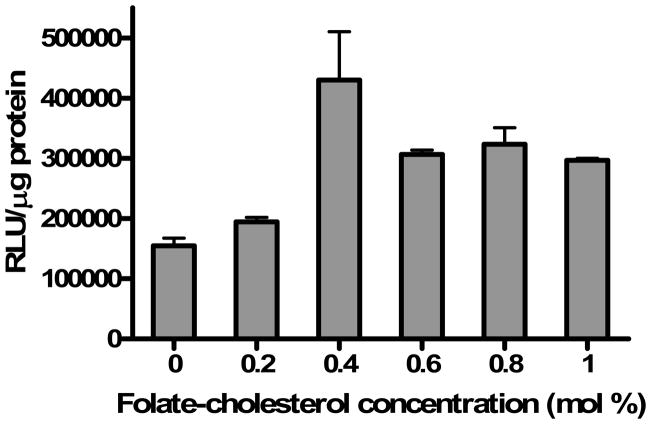

In order to optimize ligand concentrations for transfection experiments, folate-cholesterol was incorporated into lipoplexes prepared with DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69). KB cells that overexpress the folate receptor on their cell surface were then transfected by lipoplexes with various concentrations of folate-cholesterol in a medium containing 50% FBS. The high serum concentration was utilized to simulate conditions that the lipoplex and ligand would experience upon intravenous administration. The optimal transfection efficiency was observed at the concentration of 0.4 mol% folate-cholesterol, with approximately a 3-fold increase as compared to the control lacking ligand (Fig. 2). Higher ligand concentrations (> 0.4 mol %) did not further improve transfection rates in KB cells, and transfection efficiency actually decreased slightly at higher ligand concentrations. Therefore, further experiments employed lipoplexes prepared with 0.4 mol% folate ligand.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Folate-cholesterol concentration in lipoplexes with DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69) on transfection of KB cells in 50% serum. The data represent the mean + one standard deviation of three replicates.

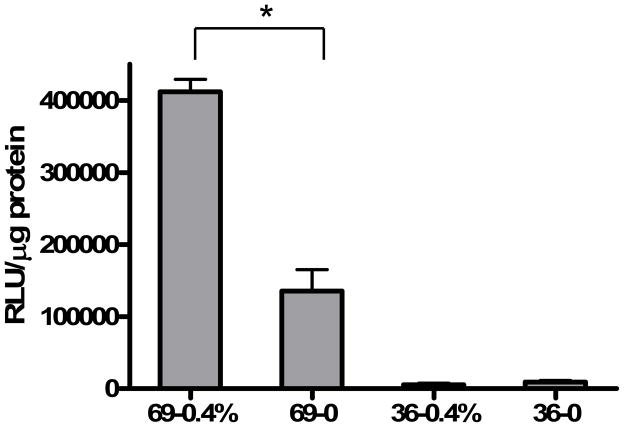

Lipoplexes with 36% cholesterol were then prepared to investigate the effect of cholesterol domain formation on ligand-mediated transfection. In the formulation with 36% cholesterol, inclusion of 0.4% folate-cholesterol does not show enhanced transfection as compared to the no ligand control (Fig. 3), in contrast to the result with lipoplexes formulated with 69% cholesterol. Considering that the cholesterol domain is formed at cholesterol concentrations of 52 wt% or above 27, it appears that the enhancement of transfection by the ligand is achieved only in formulations possessing a cholesterol nanodomain. Consistent with our hypothesis that nanodomains offer an improved anchoring site for ligands, these results demonstrate that the ability of folate-cholesterol to facilitate gene delivery is augmented by the presence of a cholesterol nanodomain.

Fig. 3.

In vitro transfection of DOTAP/cholesterol lipoplexes prepared with 36 and 69 weight percent cholesterol. KB cells were transfected by lipoplexes with or without 0.4 mol% folate-cholesterol in 50% serum. The data represent the mean + one standard deviation of three replicates. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) between formulations with and without ligand in formulations possessing 80% cholesterol.

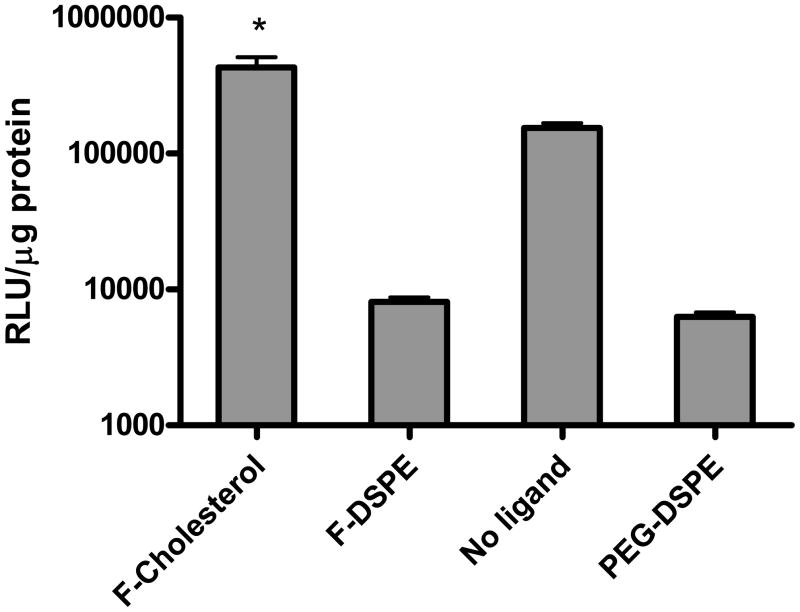

Effect of ligand anchor on transfection

To further test the effect of the cholesterol nanodomain on folate-mediated targeting, lipoplexes were prepared with DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69) and two different folate conjugates, i.e. folate-cholesterol and folate-DSPE. The latter conjugate will be excluded from the cholesterol nanodomain, whereas the former will partition into the nanodomain. Lipoplexes with PEG-DSPE or no ligand were included as controls. In figure 4, the PEGylated lipoplexes (i.e. with PEG-DSPE) showed the lowest transfection, and attachment of the targeting ligand (folate) at the distal end of PEG-DSPE resulted in only a slight improvement. In comparison, transfection efficiency increased dramatically (over 50-fold) when the folate ligand was conjugated to cholesterol instead of DSPE (Fig. 4). It is important to note that much of this enhancement was due to the absence of the DSPE conjugates that decreased the transfection rate dramatically. However, the use of the folate-cholesterol conjugate still resulted in significantly higher expression (3-fold) as compared to the untargeted formulation.

Fig. 4.

In vitro transfection of DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69) lipoplexes prepared with different ligand conjugates at the concentration of 0.4 mol%. Lipoplexes with no ligand or PEG-DSPE were used as controls. The data represent the mean + one standard deviation of three replicates. F-cholesterol: folate-cholesterol; F-DSPE: folate-DSPE. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between formulations lacking a ligand and those incorporating folate-cholesterol.

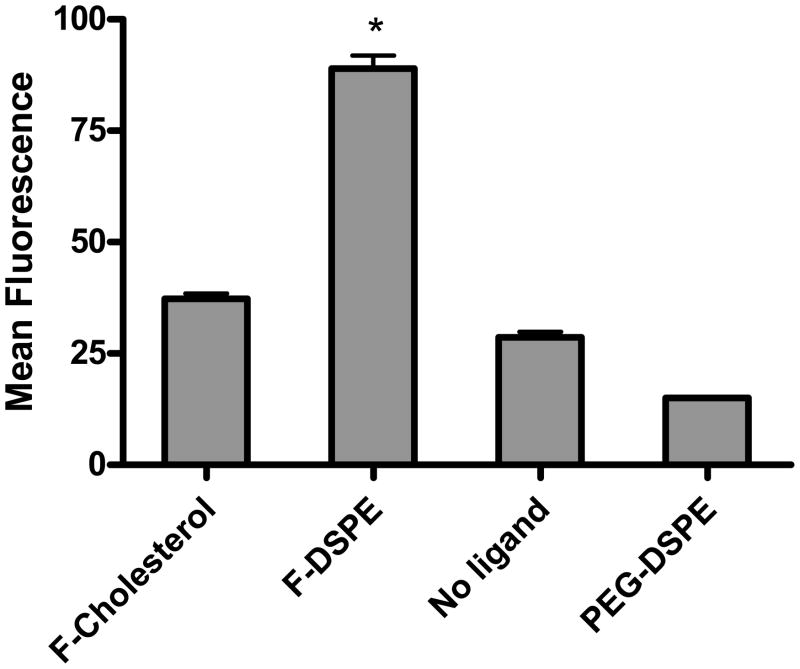

Uptake of lipoplexes in KB cells

Lipoplexes containing 0.4 mol% lipid conjugate were fluorescently labeled with 1 mol% of NBD-DOPE to quantify the cellular uptake of lipoplexes by KB cells. Cellular uptake of lipoplexes was measured by flow cytometry after a 4 hr incubation in media containing 50% FBS. As shown in figure 5, lipoplexes formulated with folate-DSPE showed the highest cellular uptake, and formulations incorporating PEG-DSPE showed the lowest level of uptake. Interestingly, cellular uptake of lipoplexes was not greatly enhanced by the folate-cholesterol, which is only approximately 40% of that with folate-DSPE. This finding is contradictory to the transfection results, suggesting that the enhanced transfection cannot be explained by increased cellular uptake. Furthermore, cellular uptake level is relatively the same in formulations with folate-cholesterol or no ligand even though these formulations exhibit significantly different transfection rates. Parallel experiments using confocal microscopy to assess changes in intracellular trafficking did not reveal consistent differences among the formulations with regard to accumulation in endosomes or nuclei (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Cellular uptake of DOTAP/cholesterol (wt/wt: 31/69) lipoplexes with different ligand conjugates. The mean fluorescence intensity measured by FACS was interpreted as a direct measure of cellular uptake of lipoplexes. The data represent the mean + one standard deviation of three replicates. F-cholesterol: folate-cholesterol; F-DSPE: folate-DSPE. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p<0.05) between lipoplexes incorporating folate-DSPE and other formulations.

Discussion

It has been shown that anhydrous cholesterol domains form in DOTAP/cholesterol liposomes and lipoplexes when formulated at 69% cholesterol 27. In the present study, conjugates including folate-cholesterol, folate-DSPE and PEG-DSPE were incorporated into lipoplexes containing high cholesterol content to determine the effect of ligand location (inside vs. outside the nanodomain) on folate-mediated gene delivery in vitro. As shown in figure 1, cholesterol domain formation is not affected by the presence of the targeting ligand, which is still detectable by a transition of anhydrous cholesterol at 38–40°C on a DSC heating scan. Furthermore, the area under the transition curve remains virtually constant in all the samples with or without targeting ligands, consistent with the very low level of lipid conjugate used in our experiments (i.e., 0.4 mol%).

Figure 3 shows that lipoplexes formulated at cholesterol contents that support the formation of a cholesterol domain exhibit much higher transfection activity under our conditions (50% serum) than lipoplexes lacking a domain, consistent with our previous work 27. When folate-cholesterol was incorporated into each of these formulations, dramatically different effects were observed suggesting that the presence of a domain affects the ability of the ligand to facilitate transfection. More specifically, the ligand did not enhance transfection in formulations lacking a domain, but increased transfection rates 3-fold (relative to that formulation lacking a ligand) when incorporated in a formulation possessing a cholesterol nanodomain. While the effect of the cholesterol nanodomain (in and of itself) is significant (15-fold), these results also demonstrate that additional enhancement can be achieved if ligands are present within the domain. Overall, the effect of utilizing formulations with both the cholesterol nanodomain and the folate-cholesterol ligand was to increase transfection in KB cells by approximately 50-fold in comparison to the formulation lacking a cholesterol domain.

To further test the effect of locating ligands in the cholesterol nanodomain, we compared the effects of different folate conjugates (folate-cholesterol and folate-DSPE) on transfection and uptake. In this regard, it is important to note that folate-cholesterol is able to partition into the cholesterol domain while folate-DSPE is not able to do so because the diacyl phospholipid anchor (DSPE) would be excluded from the pure cholesterol domain. Surprisingly, the results indicate that incorporation of folate-DSPE significantly reduces transfection despite enhancing cell uptake (Figs 4 and 5). Considering that PEG 2000 was used to link folate to DSPE, it is possible that the decreased transfection was due to the well-established inhibitory effect of PEG on transfection rates in cell culture 7. Our results employing PEG-DSPE are consistent with this hypothesis and demonstrate that even this relatively low level of PEGylation (0.4 mol%) reduces both transfection and uptake. But, the fact that transfection rates were not improved even though uptake was enhanced by the folate-DSPE conjugate suggests that the detrimental effects of PEGylation on transfection are not due to reductions in cell uptake. Although it is possible that higher concentrations of folate-DSPE would be able to overcome the inhibitory effects of PEGylation, the fact that transfection rates remained low in spite of increased uptake is consistent with studies suggesting that PEGylation reduces transfection by altering intracellular trafficking 7, 9–11, 31, 32.

In contrast to our results with folate-DSPE, conjugation of the ligand to cholesterol increased transfection rates approximately 3-fold (Fig. 4); consistent with the results in figure 3. Surprisingly, location of the ligand within the cholesterol domain did not dramatically improve uptake (Fig. 5), suggesting that the domain promotes more productive intracellular trafficking that enhances transfection rates. It is important to point out that lipoplexes formulated with a cholesterol nanodomain exhibited significantly lower transfection rates if the ligand was not incorporated into the formulation. This suggests that location of the ligand within the cholesterol nanodomain induces productive trafficking above and beyond that endowed by the domain itself. Although we did not observe consistent differences in trafficking by confocal microscopy, it is clear that differences in uptake cannot explain the enhanced transfection observed when lipoplexes were formulated with folate-cholesterol.

It has been shown that particle size appears to be an important factor that determines the mechanism of particle internalization into cells 33. There is a general agreement that endocytosis is the major pathway of lipoplex entry into eukaryotic cells, although distinctive pathways exist with clathrin-dependent and caveolae-mediated internalization being the two major ones. Particles with a size of 200 nm or less have been shown to enter cells exclusively by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, while caveolae-mediated internalization was seen for particles with a larger diameter 33. More importantly, caveolae-mediated trafficking appears to go through a non-acidic and non-digestive pathway, which avoids lysosomal degradation of lipoplexes 34. Study by Rejman et al has even stated that only caveolae-mediated internalization caused productive transfection 35. In our present study, particle sizes of all the formulations are within 150 to 200 nm, and therefore uptake of all these particles should occur via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Similarly, the zeta potential of our lipoplexes is relatively comparable with different ligands, suggesting that differences in surface charge are not likely to explain our observations. A recent study by Caracciolo et al showed that surface adsorption of the protein corona on DC-Chol-DOPE/DNA complexes could control the cell internalization pathway in serum 36. Considering this intriguing possibility, cholesterol domains may either inhibit the adsorption of proteins that trigger non-productive uptake or, conversely, attract serum proteins that promote productive uptake. A mechanism invoking differential protein adsorption could potentially explain the enhanced transfection observed with formulations possessing a cholesterol nanodomain (Fig. 3 27). However, it is more difficult to explain the enhanced transfection with folate-cholesterol, in spite of minimal increases in uptake, by this mechanism. While it is possible that the ligand itself might be involved in recruiting proteins to the surface, the fact that the identical ligand did not enhance transfection when excluded from the domain renders such an explanation less likely.

We conclude that both the presence of a cholesterol nanodomain and the location of ligands within the nanodomain enhance transfection without increasing cellular uptake. We suggest that this effect must involve differences in cellular trafficking such that lipoplexes that are internalized by the cells are shuttled to different pathways within the cytoplasm. Our results indicate that both the cholesterol nanodomain and the presence of ligand within the domain contribute to more productive uptake pathways that have yet to be elucidated. Based on recent studies showing that the adsorption of protein can affect intracellular trafficking, we suggest that differential protein adsorption may play a role in our observations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants #BES-0433811 (NSF) and #EB0005476-01A2 (NIH-NIBIB) to TJA.

References

- 1.Yang JP, Huang L, Yang JP, Huang L. Gene Ther. 1998;5(3):380–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crook K, Stevenson BJ, Dubouchet M, Porteous DJ. Gene Ther. 1998;5(1):137–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Tseng WC, Stolz DB, Wu SP, Watkins SC, Huang L. Gene Ther. 1999;6(4):585–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Anchordoquy TJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1663(1–2):143–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torchilin VP, Shtilman MI, Trubetskoy VS, Whiteman K, Milstein AM, Torchilin VP, Omelyanenko VG, Papisov MI, Bogdanov AA, Jr, Trubetskoy VS, Herron JN, Gentry CA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1195(1):181–4. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torchilin VP, Omelyanenko VG, Papisov MI, Bogdanov AA, Jr, Trubetskoy VS, Herron JN, Gentry CA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1195(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvie P, Wong FM, Bally MB. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89(5):652–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6017(200005)89:5<652::AID-JPS11>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabizon A, Papahadjopoulos D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(18):6949–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyvonen Z, Ronkko S, Toppinen MR, Jaaskelainen I, Plotniece A, Urtti A. J Control Release. 2004;99(1):177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi F, Wasungu L, Nomden A, Stuart MC, Polushkin E, Engberts JB, Hoekstra D. Biochem J. 2002;366(Pt 1):333–41. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong TK, Girouard LG, Anchordoquy TJ. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(12):2549–58. doi: 10.1002/jps.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodle MC, Scaria P, Ganesh S, Subramanian K, Titmas R, Cheng C, Yang J, Pan Y, Weng K, Gu C, Torkelson S. J Control Release. 2001;74(1–3):309–11. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogris M, Walker G, Blessing T, Kircheis R, Wolschek M, Wagner E. J Control Release. 2003;91(1–2):173–81. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbaan FJ, Oussoren C, Snel CJ, Crommelin DJ, Hennink WE, Storm G. J Gene Med. 2004;6(1):64–75. doi: 10.1002/jgm.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li SD, Chono S, Huang L. J Control Release. 2008;126(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L, Huang CC, Huang W, Tang WH, Rait A, Yin YZ, Cruz I, Xiang LM, Pirollo KF, Chang EH. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(5):337–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruckheimer E, Harvie P, Orthel J, Dutzar B, Furstoss K, Mebel E, Anklesaria P, Paul R. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11(2):128–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvie P, Dutzar B, Galbraith T, Cudmore S, O’Mahony D, Anklesaria P, Paul R. J Liposome Res. 2003;13(3–4):231–47. doi: 10.1081/lpr-120026389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mamot C, Drummond DC, Noble CO, Kallab V, Guo Z, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Park JW. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11631–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis ME. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(3):659–68. doi: 10.1021/mp900015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez CA, Rice KG. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(5):1277–89. doi: 10.1021/mp900033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weitman SD, Lark RH, Coney LR, Fort DW, Frasca V, Zurawski VR, Jr, Kamen BA. Cancer Res. 1992;52(12):3396–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross JF, Chaudhuri PK, Ratnam M. Cancer. 1994;73(9):2432–43. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940501)73:9<2432::aid-cncr2820730929>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhai G, Wu J, Xiang G, Mao W, Yu B, Li H, Piao L, Lee LJ, Lee RJ. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2009;9(3):2155–61. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshizawa T, Hattori Y, Hakoshima M, Koga K, Maitani Y. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;70(3):718–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng H, Zhu JL, Zeng X, Jing Y, Zhang XZ, Zhuo RX. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;3:3. doi: 10.1021/bc8004057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu L, Anchordoquy TJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778(10):2177–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(38):14265–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao XB, Muthusamy N, Byrd JC, Lee RJ. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96(9):2424–35. doi: 10.1002/jps.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison SD, Molina MC, Anchordoquy TJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1468(1–2):127–38. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monck MA, Mori A, Lee D, Tam P, Wheeler JJ, Cullis PR, Scherrer P. J Drug Target. 2000;7(6):439–52. doi: 10.3109/10611860009102218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tam P, Monck M, Lee D, Ludkovski O, Leng EC, Clow K, Stark H, Scherrer P, Graham RW, Cullis PR. Gene Ther. 2000;7(21):1867–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. Biochem J. 2004;377(Pt 1):159–69. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoekstra D, Rejman J, Wasungu L, Shi F, Zuhorn I. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 1):68–71. doi: 10.1042/BST0350068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rejman J, Bragonzi A, Conese M. Mol Ther. 2005;12(3):468–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caracciolo G, Callipo L, De Sanctis SC, Cavaliere C, Pozzi D, Lagana A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798(3):536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]