Abstract

We present the perspective that lactate is a volume transmitter of cellular signals in brain that acutely and chronically regulate the energy metabolism of large neuronal ensembles. From this perspective, we interpret recent evidence to mean that lactate transmission serves the maintenance of network metabolism by two different mechanisms, one by regulating the formation of cAMP via the lactate receptor GPR81, the other by adjusting the NADH/NAD+ redox ratios, both linked to the maintenance of brain energy turnover and possibly cerebral blood flow. The role of lactate as mediator of metabolic information rather than metabolic substrate answers a number of questions raised by the controversial oxidativeness of astrocytic metabolism and its contribution to neuronal function.

Keywords: lactate, lactate receptor, central fatigue, metabolic information, volume transmission

Here, we present the perspective that lactate acts as a volume transmitter in brain tissue by distributing cellular signals that are relevant to the metabolic support of large neuronal ensembles. We interpret recent evidence to mean that lactate transmission is involved in the maintenance of network homeostasis by two different mechanisms; one by regulation of neuronal cAMP formation through the lactate receptor GPR81, the other by adjustment of the NADH/NAD+ redox ratio. Lactate is an intermediary metabolite in brain energy metabolism, the role of which is controversial (Dienel, 2011). Traditionally, lactate was considered a waste product with no certain function in the metabolic housekeeping when eukaryotic cells have sufficient oxygen. However, it is also held to be a “preferred” substrate of energy metabolism, in muscle (Brooks, 2009) as well as in brain (Bouzier-Sore et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2003; Wyss et al., 2011). This alleged preference revives an ancient claim of lactate’s service as nutrient for neurons that do not phosphorylate glucose to the extent required by neuronal energy metabolism (Andriezen, 1893; DiNuzzo et al., 2011). A cue to the notion of a signaling role of lactate, irrespective of any role as intermediary metabolite, is the observation that lactate regulates cerebral blood flow (Gordon et al., 2008).

VOLUME TRANSMISSION

The concept of volume transmission, introduced by Luigi Agnati and Kjell Fuxe in 1986, designates is a form of communication in brain tissue in which modulators act across wide distances when their sites of release and removal are further apart than for “wired” transmission, characteristic of focused synaptic action (Fuxe et al., 2010). Volume transmission affects large volumes of tissue and undergoes change more slowly than wired transmission. The concept of volume transmission in brain therefore overlaps with forms of paracrine and autocrine signaling. The canonical volume transmitters are monoamines, released from varicosities along the fibers of monoaminergic neurons and removed by transporters at sites reached after variable distances of diffusion. However, the list of potential agents of volume transmission is long, as any molecule that engages receptors, transporters, or enzymes far from a place of synthesis or release may qualify as a volume transmitter, including the archetypical wired transmitter glutamate (Okubo and Iino, 2011). Another potential volume transmitter is L-DOPA, which shares with lactate the ability to move across cellular membranes and reach cells far from the sites of generation (Gjedde et al., 1993; Ugrumov, 2009).

LACTATE RECEPTOR GPR81

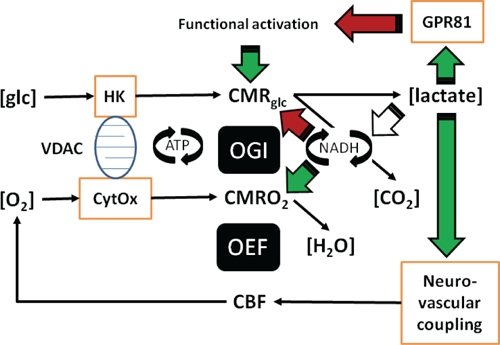

The G-protein-coupled 7TM receptor (GPR) family includes members that mediate specific actions of hydroxyl carboxylic acids (HCA), including GPR81, also known as HCA1 receptor (Blad et al., 2011), which serves lactate’s downregulation of cAMP, as shown in adipocytes (Ahmed et al., 2009). The GPR81 is prominent in adipose tissue, where it inhibits lipolysis, but it is known also to be expressed in a wider range of organs such as liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, spleen, and testis (Gantz et al., 1997; Ge et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Rooney and Trayhurn, 2011). Evidence from in situ hybridization show a widespread distribution of GPR81 mRNA in the brain, predominantly in neurons, including the principal neurons in cortex, hippocampus (pyramidal and granule cells), and cerebellum (granule cells), while labeling of astrocytes cannot be excluded (The Allen Institute for Brain Science1, GENSTAT2, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital3). The receptor’s reported affinities for L-lactate range from 1.3 to 5 mM (Cai et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009), which is consistent with the range of lactate concentrations measured in brain tissue in vivo (Abi-Saab et al., 2002). The binding of lactate to GPR81 attenuates the formation of cAMP, which in turn inhibits protein kinase A and hence glycogenolysis, leading to decreases of glucose-1-phosphate and glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) that affect glycolysis in the cytosol, as recently shown by kinetic modeling (DiNuzzo et al., 2010). The decrease of G6P affects its role as allosteric regulator of hexokinase (HK), including the association of HK with the voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC) in the outer mitochondrial membrane, with important consequences for the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation of ADP (Wilson, 2003; Mailloux and Harper, 2011). The main thrust of this perspective is the importance of any physical separation of HK and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activities, which would lead to diffusion of lactate between the sites. As such, this concept is not limited to major compartments or cell types but applies equally well to subdivisions of cells, such as distal vs proximal dendrites and astrocytic processes vs cell bodies rather than to astrocyte/neuron differences (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

In this illustration you can follow the two different mechanisms proposed: (a) Lactate regulates the formation of cAMP via the lactate receptor GPR81. (b) Lactate adjusts the NADH/NAD+ redox ratio. (c) Both the formation of cAMP and the adjustment of NADH/NAD+ redox ratio can be linked to the maintenance of brain energy turnover and neurovascular coupling. The role of lactate in neurovascular coupling is included in the figure, but not dealt with in the text, which focuses on cellular effects of lactate in brain tissue. The roles of lactate as mediator of metabolic information rather than metabolic substrate answer a number of questions raised by the aerobic glycolysis of astrocytes and its controversial contribution to neuronal function.

CYTOSOLIC AND MITOCHONDRIAL NADH/NAD+ REDOX RATIOS AND LACTATE DEHYDROGENASES

Lactic and pyruvic acids interact through the actions of the cytosolic near-equilibrium lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) isozymes, which reflect the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratios in cytosol. The cytosolic and the mitochondrial redox states are linked through a network of redox reactions and inner membrane transport processes, but the exact relation between cytosolic and mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ ratios is not known. There are reports of mitochondrial LDH activity (Brooks, 2009) and therefore potential for coupling of lactate–pyruvate and NADH/NAD+ ratios in the mitochondrial matrix. Changes of the NADH/NAD+ redox ratios trigger several intracellular responses, including expression of genes by modification of histone deacetylases, which profoundly affect the regulation of protein synthesis. For example sirtuins, gene-regulating histone deacetylases with effects on regulation of caloric intake, metabolism and age-related diseases (Finkel et al., 2009), are tightly redox regulated through the NADH/NAD+ ratio (Gambini et al., 2011). Genes activated by lactate through lactate-sensitive response elements include c-fos, c-jun, c-ets, Hyal-1, Hyal-2, CD44, and caveolin-1 (Formby and Stern, 2003). The DNA binding of the transcription factor fos– jun heterodimer AP-1 depends on a specific cysteine residue being in the reduced sate (Abate et al., 1990), acting as a redox sensor. In addition, pyruvate, which interacts closely with lactate as dictated by the NADH/NAD+ ratio, is a gene regulator through histone deacetylase inhibition (Thangaraju et al., 2009; Rajendran et al., 2011).

NEAR-EQUILIBRIUM REACTIONS AND LACK OF COMPARTMENTATION

Both the LDH isozymes and the monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCT) of the blood–brain barrier and cell membranes of brain tissue mediate near-equilibrium transfer of lactate (Bergersen et al., 2001; Bergersen, 2007) when unidirectional fluxes exceed net fluxes by several orders of magnitude. Therefore LDH and MCT proteins serve to dissipate lactate concentration differences across cell membranes and tissue volumes. Thus, changes of pyruvate and lactate concentrations in one place lead to similar changes of lactate concentrations across large volumes of brain tissue over long times. In turn, any effects of changes of lactate on the NADH/NAD+ ratio in one place lead to similar effects in widely distributed populations of cells (cf. Cerdán et al., 2006; Ramírez et al., 2007; Rodrigues et al., 2009). In fact, the transfer of lactate is so efficient that it is difficult to observe any differences of lactate concentrations across cell membranes in brain tissue (Gjedde and Marrett, 2001; Ido et al., 2001, 2004; Gjedde et al., 2002), such that significant cellular compartmentation of lactate is unlikely to exist under normal conditions, except briefly. The high concentration of MCT2 at the PSD of fast excitatory synapses co-localized with glutamate receptors (Bergersen et al., 2001, 2005) suggests a particular need for lactate transfer at these synapses perhaps involved in volume transmission signaling. In addition to moving through brain tissue by facilitated transfer across plasma membranes of all cells through MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4, and by diffusion through the extracellular space, lactate spreads through the astroglial network in which individual astrocytes are connected by gap junctions (Dienel, 2011; Mathiesen et al., 2011). One puzzle is the kinetic differences among the isozymes of LDH (O’Brien et al., 2007), the physiological role of which at near-equilibrium is not yet understood (Ross et al., 2010; Quistorff and Grunnet, 2011; Ross, 2011), but may be related to the proposed function of lactate as a volume transmitter in cytosolic and perhaps mitochondrial environments with widely differing NADH/NAD+ ratios (Figure 1).

NON-STEADY-STATES AND ACTIVATION

The purported changes of lactate concentrations and the consequent redistribution of lactate happen whenever and wherever sites of generation and metabolic conversion of pyruvate are unmatched or physically separated. Pyruvate is the main end product of aerobic glycolysis, which is controlled by the concerted action of the HK and phosphofructokinase (PFK) enzyme complex, while the fate of pyruvate is determined by the PDH complex in mitochondria. The two enzyme complexes are the main flux-generating determinants of brain energy metabolism as controlled by allosteric effectors, and both therefore define the path that is open to the respective so-called “pathway substrates,” glucose in the case of the HK–PFK complex, pyruvate in the case of the PDH complex (Gjedde, 2007). The temporal and spatial integration of the activities of these enzyme complexes is then the key to the dynamics of lactate inside and among the cells of brain tissue. Both the oxygen–glucose index (OGI) and the oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) decline during the temporary departures from steady-state associated with functional activation of brain regions, attributed to increased aerobic glycolysis (Madsen et al., 1999; Schmalbruch et al., 2002). The declines are signs of focal disintegration of the HK–PFK and PDH activities, resulting in increased lactate–pyruvate ratios, redistribution of lactate and adjustment of NADH/NAD+ ratios within the sphere of action of the redistributed lactate. This process seems to be so efficient that it leaves no oxygen deficit or abnormal ATP, ADP, or AMP levels, even in seizures (Larach et al., 2011).

Extracellular lactate concentrations increase during neuronal and synaptic activation in vivo, as determined by microdialysis (Uehara et al., 2008; Bero et al., 2011), and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy minutes after stimulation (Prichard et al., 1991; Sappey-Marinier et al., 1992; Maddock et al., 2006), following a transient decrease 5 s after stimulation (Mangia et al., 2003). These observations are consistent with adjustments that follow the perturbation of an existing steady-state and the subsequent return to a potential new steady-state, depending on conditions, such as the intensity of the continuing neuronal activation. The lactate dynamics are uniquely dependent on the shifts among these steady- and non-steady-states of brain energy metabolism. The observations that the OGI declines during the non-steady-state of the early stages of functional brain activation, signifies increased lactate production in the tissue as a whole, evidently due to increased glucose consumption relative to oxygen consumption. The observations are consistent with changes of glucose consumption that match the changes of blood flow during activation, while changes of oxygen consumption generally do not (Gjedde et al., 2002; Paulson et al., 2010). Recent evidence also shows that the changes of glucose consumption exceed the changes of oxygen consumption at specific regional locations (Vaishnavi et al., 2010), rather than everywhere, creating the gradients of lactate concentration that serve to redistribute lactate inside as well as outside cells and across the blood–brain barrier. The regional variation of the OGI (Vaishnavi et al., 2010) may possibly be related to different ratios of cell types (low in cortex with numerous astrocytes, high in cerebellum with numerous neurons). Any separation of the sites of lactate generation and lactate metabolism inside or among cells therefore must result in shuttling of lactate among its sites of generation and metabolism. The fluxes alter the interactions with enzymes and transporters that qualify as volume transmission. Thus, the temporal and spatial mismatches of lactate generation and metabolism arise because different cellular and subcellular compartments react differently to activating stimuli (Gjedde et al., 2005; Vaishnavi et al., 2010).

CENTRAL vs PERIPHERAL FATIGUE

Physical exertion generates considerable increases of lactate concentration in the circulation. It has been shown by MR spectroscopy that blood lactate is an efficient substrate for the brain, and especially for neurons, both in rat (Bouzier et al., 2000; Hassel and Bråthe, 2000) and in humans (Boumezbeur et al., 2010). The increased lactate also has effects on brain metabolism, which are characterized by reduction of the cerebral OGI in the context of a state known as “central fatigue” (Dalsgaard, 2006; Dalsgaard and Secher, 2007; Rasmussen et al., 2010). Central fatigue precedes the muscle fatigue that also relates to increased lactate (van Hall, 2010). The mechanism responsible for the onset of central fatigue is not known with certainty but appears to be related to decreased oxygen delivery, which in turn may be due to increased lactate in brain tissue and possible effects on lactate’s receptor GPR81 (Rasmussen et al., 2010; Gam et al., 2011). The downregulation of cAMP formation by binding of lactate to GPR81 offers a novel explanation of central fatigue and “over-training” distress (Lehmann et al., 1993), and possibly in part the asthenia seen in advanced cancer, a condition that is known to be characterized by chronically increased blood lactate levels (Koppenol et al., 2011). Chronically increased lactate levels similarly are held to be characteristic of old age and dementia, based on the properties of a mtDNA mutator mouse model (Ross et al., 2010). These effects contrast with the upregulation of cAMP by noradrenaline with effects such as arousal and enhanced brain performance (Berridge, 2008).

Many other observed effects of lactate on neuronal function may result from enzyme- or receptor-mediated responses rather than from the direct actions of lactate as a metabolic substrate. For example, the observation that lactate administration protects against ischemia (Schurr et al., 1997, 2001; Cureton et al., 2010) has been ascribed to enhanced neuronal energy turnover. However, this is not readily explained by metabolic effects, as lactate metabolism cannot raise energy turnover under ischemic conditions, although after ischemia and in the penumbra of vascular occlusion, the availability of lactate for oxidation may assist in alleviating ischemia induced damage (Schurr et al., 2001; Berthet et al., 2009). Similarly, the observed protective effect of lactate on glutamate toxicity in the brain (Ros et al., 2001) may be due to receptor-mediated inhibition, rather than the simple satisfaction of the metabolic demands of neurons exposed to high concentrations of glutamate (Schurr et al., 1999). In microdialysis of the cerebral cortex, excitotoxic concentrations of glutamate raised lactate at the expense of glucose in the dialysate. The addition of L-lactate caused the lesion to become smaller and abolished the decrease of glucose. Replacing L-lactate with the non-physiological D-lactate isomer expanded the lesion and raised L-lactate in the dialysate above the level observed with glutamate alone (Ros et al., 2001), consistent with the claim that endogenously produced lactate is neuroprotective by means of receptor interaction.

The suppression of noradrenalin and adrenalin releases by blood lactate clamps at 4 mM (Fattor et al., 2005) also suggests a receptor mechanism, consistent with the postulated reduction of cAMP formation by GRP81 activation. Interestingly, also β-adrenoceptor blockers, which presumably act by reducing intracellular cAMP, are neuroprotective in stroke and other brain injuries, and also lower extracellular glutamate levels, which may further limit excitotoxic cell damage (Goyagi et al., 2011).

CONCLUSION

The proposed role of lactate as a mediator of information on changing NADH/NAD+ ratios among the cells of brain tissue has implications for the understanding of regulation of brain energy metabolism, including the communication between cytosol and mitochondria in large populations of cells (Xu et al., 2007). Lactate’s inhibition of cAMP formation through G-protein-coupled receptors may be a factor in the development of central fatigue. An action of lactate may therefore be to “smooth” the non-steady-states that underlie the mismatches of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, induced by needs for aerobic glycolysis that satisfy the short time constants of ATP turnover required for maintenance of rapid de- and repolarizations. The redistribution of lactate by the volume transmission is both temporal and spatial and potentially reaches large volumes of tissue, aided by the extended syncytium of astrocytic networks connected by gap junctions. The role of lactate as informant of metabolic states rather than substrate of metabolism solves a number of puzzles that contribute to the controversy surrounding the understanding of astrocytic metabolism and its contribution to neuronal function.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Abate C., Patel L., Rauscher F. J., Curran T.(1990). Redox regulation of fos and jun DNA-binding activity in vitro. Science 249 1157–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Saab W. M., Maggs D. G., Jones T., Jacob R., Srihari V., Thompson J., Kerr D., Leone P., Krystal J. H., Spencer D. D., During M. J., Sherwin R. S. (2002). Striking differences in glucose and lactate levels between brain extracellular fluid and plasma in conscious human subjects: effects of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 22 271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K., Tunaru S., Offermanns S.(2009). GPR109A, GPR109B and GPR81, a family of hydroxy-carboxylic acid receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30 557–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriezen W. L. (1893). The neuroglia elements in the human brain. Br. Med. J. 29 227–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergersen L. H. (2007). Is lactate food for neurons? Comparison of monocarboxylate transporter subtypes in brain and muscle. Neuroscience 145 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergersen L., Waerhaug O., Helm J., Thomas M., Laake p., Davies A. J., Wilson M. C., Halestrap A. P., Ottersen O. P. (2001). A novel postsynaptic density protein: the monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 is co-localized with delta-glutamate receptors in postsynaptic densities of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Exp. Brain Res. 136 523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergersen L. H., Magistretti P. J., Pellerin L.(2005). Selective postsynaptic co-localization of MCT2 with AMPA receptor GluR2/3 subunits at excitatory synapses exhibiting AMPA receptor trafficking. Cereb. Cortex 15 361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero A. W., Yan P., Roh J. H., Cirrito J. R., Stewart F. R., Raichle M. E., Lee J. M., Holtzman D. M. (2011). Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-β deposition. Nat. Neurosci. 14 750–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge C. W. (2008). Noradrenergic modulation of arousal. Brain Res. Rev. 58 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet C., Lei H., Thevenet J., Gruetter R., Magistretti P. J., Hirt L.(2009). Neuroprotective role of lactate after cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 29 1780–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blad C. C., Ahmed K., Ijzerman A. P., Offermanns S.(2011). Biological and pharmacological roles of HCA receptors. Adv. Pharmacol 62 219–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumezbeur F., Mason G. F., de Graaf R. A., Behar K. L., Cline G. W., Shulman G. I., Rothman D. L., Petersen K. F. (2010). Altered brain mitochondrial metabolism in healthy aging as assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30 211–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzier A. K., Thiaudiere E., Biran M., Rouland R., Canioni P., Merle M.(2000). The metabolism of [3-(13)C]lactate in the rat brain is specific of a pyruvate carboxylase-deprived compartment. J. Neurochem. 75 480–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzier-Sore A. K., Serres S., Canioni P., Merle M.(2003). Lactate involvement in neuron-glia metabolic interaction: (13)C-NMR spectroscopy contribution. Biochimie 85 841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks G. A. (2009). Cell–cell and intracellular lactate shuttles. J. Physiol. 587 5591–5600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T. Q., Ren N., Jin L., Cheng K., Kash S., Chen R., Wright S. D., Taggart A. K., Waters M. G. (2008). Role of GPR81 in lactate-mediated reduction of adipose lipolysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377 987–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdán S., Rodrigues T. B., Sierra A., Benito M., Fonseca L. L., Fonseca C. P., García-Martín M. L. (2006). The redox switch/redox coupling hypothesis. Neurochem. Int. 48 523–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cureton E. L., Kwan R. O., Dozier K. C., Sadjadi J., Pal J. D., Victorino G. P. (2010). A different view of lactate in trauma patients: protecting the injured brain. J. Surg. Res. 159 468–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard M. K. (2006). Fuelling cerebral activity in exercising man. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26 731–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard M. K., Secher N. H. (2007). The brain at work: a cerebral metabolic manifestation of central fatigue? J. Neurosci. Res. 85 3334–3339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienel G. A. (2011). Brain lactate metabolism: the discoveries and the controversies. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.175 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNuzzo M., Gili T., Maraviglia B., Giove F.(2011). Modeling the contribution of neuron-astrocyte cross talk to slow blood oxygenation level-dependent signal oscillations. J. Neurophysiol. 106 3010–3018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNuzzo M., Mangia S., Maraviglia B., Giove F.(2010). Glycogenolysis in astrocytes supports blood-borne glucose channeling not glycogen-derived lactate shuttling to neurons: evidence from mathematical modeling. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1895–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattor J. A., Miller B. F., Jacobs K. A., Brooks G. A. (2005). Catecholamine response is attenuated during moderate-intensity exercise in response to the “lactate clamp”. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 288 143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T., Deng C. X., Mostoslavsky R. (2009). Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature 460 587–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formby B., Stern R. (2003). Lactate-sensitive response elements in genes involved in hyaluronan catabolism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305 203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K., Dahlström A. B., Jonsson G., Marcellino D., Guescini M., Dam M., Manger P., Agnati L.(2010). The discovery of central monoamine neurons gave volume transmission to the wired brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 90 82–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gam C. M. B., Nielsen H. B., Secher N. H., Larsen F. S., Ott P., Quistorff B.(2011). In cirrhotic patients reduced muscle strength is unrelated to muscle capacity for ATP turnover suggesting a central limitation. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 31 169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambini J., Gomez-Cabrera M. C., Borras C., Valles S. L., Lopez-Grueso R., Martinez-Bello V. E., Herranz D., Pallardo F. V., Tresguerres J. A., Serrano M., Viña J. (2011). Free [NADH]/[NAD(+)] regulates sirtuin expression. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 512 24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I., Muraoka A., Yang Y. K., Samuelson L. C., Zimmerman E. M., Cook H., Yamada T.(1997). Cloning and chromosomal localization of a gene (GPR18) encoding a novel seven transmembrane receptor highly expressed in spleen and testis. Genomics 42 462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H., Weiszmann J., Reagan J. D., Gupte J., Baribault H., Gyuris T., Chen J., Tian H., Li Y.(2008). Elucidation of signaling and functional activities of an orphan GPCR, GPR81. J. Lipid Res. 49 797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A. (2007). “Coupling of brain function to metabolism: evaluation of energy requirements (Chapter 4.4),” in Handbook of Neurochemistry: Brain Energetics from Genes to Metabolites to Cells: Integration of Molecular and Cellular Processes, 3rd Edn, eds Lajtha A., Gibson G., Dienel G. (Heidelberg/NewYork: Springer Verlag; ), 400p, 40 illus [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A., Johannsen P., Cold J. E., Østergaard L. (2005). Cerebral metabolic response to low blood flow: possible role of cytochrome oxidase inhibition. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 25 1083–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A., Léger G. C., Cumming P., Yasuhara Y., Evans A. C., Guttman M., Kuwabara H.(1993). Striatal L-DOPA decarboxylase activity in Parkinson’s disease in vivo: implications for the regulation of dopamine synthesis. J. Neurochem. 61 1538–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A., Marrett S. (2001). Glycolysis in neurons, not astrocytes, delays oxidative metabolism of human visual cortex during sustained checkerboard stimulation in vivo. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21 1384–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A., Marrett S., Vafaee M. (2002). Oxidative and nonoxida-tive metabolism of excited neurons and astrocytes. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 22 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. R., Choi H. B., Rungta R. L., Ellis-Davies G. C., MacVicar B. A. (2008). Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature 456 745–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyagi T., Nishikawa T., Tobe Y.(2011). Neuroprotective effects and suppression of ischemia-induced glutamate elevation by β1-adrenoreceptor antagonists administered before transient focal ischemia in rats. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 23 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel B., Bråthe A. (2000). Cerebral metabolism of lactate in vivo: evidence for neuronal pyruvate carboxylation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 20 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido Y., Chang K., Williamson J. R. (2004). NADH augments blood flow in physiologically activated retina and visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 653–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido Y., Chang K., Woolsey T. A., Williamson J. R. (2001). NADH: sensor of blood flow need in brain, muscle, and other tissues. FASEB J. 15 1419–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppenol W. H., Bounds P. L., Dang C. V. (2011). Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11 325–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larach D. B., Kofke W. A., Le Roux P. (2011). Potential non-hypoxic/ischemic causes of increased cerebral interstitial fluid lactate/pyruvate ratio: a review of available literature. Neurocrit. Care 15 609–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M., Foster C., Keul J.(1993). Overtraining in endurance athletes: a brief review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 25 854–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Wu J., Zhu J., Kuei C., Yu J., Shelton J., Sutton S. W., Li X., Yun S. J., Mirzadegan T., Mazur C., Kamme F., Lovenberg T. W. (2009). Lactate inhibits lipolysis in fat cells through activation of an orphan G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR81. J. Biol. Chem. 284 2811–2822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddock R. J., Buonocore M. H., Lavoie S. P., Copeland L. E., Kile S. J., Richards A. L., Ryan J. M. (2006). Brain lactate responses during visual stimulation in fasting and hyperglycemic subjects: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 1.5 Tesla Psychiatry Res. 148 47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen P. L., Cruz N. F., Sokoloff L., Dienel G. A. (1999). Cerebral oxygen/glucose ratio is low during sensory stimulation and rises above normal during recovery: excess glucose consumption during stimulation is not accounted for by lactate efflux from or accumulation in brain tissue. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 19 393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailloux R. J., and Harper M. E. (2011). Uncoupling proteins and the control of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51 1106–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangia S., Garreffa G., Bianciardi M., Giove F., Di Salle F., Maraviglia B. (2003). The aerobic brain: lactate decrease at the onset of neural activity. Neuroscience 118 7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen C., Caesar K., Thomsen K., Hoogland T. M., Witgen B. M., Brazhe A., Lauritzen M.(2011). Activity-dependent increases in local oxygen consumption correlate with postsynaptic currents in the mouse cerebellum in vivo. J. Neurosci. 31 18327–18337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J., Kla K. M., Hopkins I. B., Malecki E. A., McKenna M. C. (2007). Kinetic parameters and lactate dehydrogenase isozyme activities support possible lactate utilization by neurons. Neurochem. Res. 32 597–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo Y., Iino M. (2011). Visualization of glutamate as a volume transmitter. J. Physiol. 589 481–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson O. B., Hasselbalch S. G., Ros-trup E., Knudsen G. M., Pelligrino D. (2010). Cerebral blood flow response to functional activation J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30 2–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard J., Rothman D., Novotny E., Petroff O., Kuwabara T., Avison M., Howseman A., Hanstock C., Shulman R.(1991). Lactate rise detected by 1H NMR in human visual cortex during physiologic stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 5829–5831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistorff B., Grunnet N. (2011). The isoenzyme pattern of LDH does not play a physiological role; except perhaps during fast transitions in energy metabolism. Aging 3 457–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran P., Williams D. E., Ho E., Dashwood R. H. (2011). Metabolism as a key to histone deacetylase inhibition. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 46 181–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez B. G., Rodrigues T. B., Violante I. R., Cruz F., Fonseca L. L., Ballesteros P., Castro M. M., García-Martín M. L., Cerdán S. (2007). Kinetic properties of the redox switch/redox coupling mechanism as determined in primary cultures of cortical neurons and astrocytes from rat brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 85 3244–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen P., Nielsen J., Overgaard M., Krogh-Madsen R., Gjedde A., Secher N. H., Petersen N. C. (2010). Reduced muscle activation during exercise related to brain oxygenation and metabolism in humans. J. Physiol. 58 1985–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues T. B., López-Larrubia P., Cerdán S. (2009). Redox dependence and compartmentation of [13C]pyruvate in the brain of deuterated rats bearing implanted C6 gliomas. J. Neurochem. 109 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney K., Trayhurn P. (2011). Lactate and the GPR81 receptor in metabolic regulation: implications for adipose tissue function and fatty acid utilisation by muscle during exercise. Br. J. Nutr. 106 1310–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros J., Pecinska N., Alessandri B., Landolt H., Fillenz M. (2001). Lactate reduces glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in rat cortex. J. Neurosci. Res. 66 790–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. M. (2011). Visualization of mitochondrial respiratory function using cytochrome C oxidase/ succinate dehydrogenase (COX/SDH) double-labeling histochemistry. J. Vis. Exp. 23 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. M., Öberg J., Brené S., Coppotelli G., Terzioglu M., Pernold K., Goiny M., Sitnikov R., Kehr J., Trifunovic A., Larsson N. G., Hoffer B. J., Olson L.(2010). High brain lactate is a hallmark of aging and caused by a shift in the lactate dehydrogenase A/B ratio. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 20087–20092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappey-Marinier D., Calabrese G., Fein G., Hugg J. W., Biggins C., Weiner M. W. (1992). Effect of photic stimulation on human visual cortex lactate and phosphates using 1H and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 12 584–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalbruch I. K., Linde R., Paulson O. B., Madsen P. L. (2002). Activation-induced resetting of cerebral metabolism and flow is abolished by beta-adrenergic blockade with propranolol. Stroke 33 251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr A., Miller J. J., Payne R. S., Rigor B. M. (1999). An increase in lactate output bybrain tissue serves to meet the energy needs of glutamate-activated neurons. J. Neurosci. 19 34–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr A., Payne R. S., Miller J. J., Rigor B. M. (1997). Brain lactate is an obligatory aerobic energy substrate for functional recovery after hypoxia: further in vitro validation. J. Neurochem. 69 423–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurr A., Payne R. S., Miller J. J., Tseng M. T., Rigor B. M. (2001). Blockade of lactate transport exacerbates delayed neuronal damage in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 895 268–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D., Pernet A., Hallett W. A., Bingham E., Marsden P. K., Amiel S. A. (2003). Lactate: a preferred fuel for human brain metabolism in vivo. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23 658–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraju M., Carswell K. N., Prasad P. D., Ganapathy V. (2009). Colon cancer cells maintain low levels of pyruvate to avoid cell death caused by inhibition of HDAC1/HDAC3. Biochem. J. 417 379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T., Sumiyoshi T., Itoh H., Kurata K.(2008). Lactate production and neurotransmitters; evidence from microdialysis studies. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 90 273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugrumov M. V. (2009). Non-dopaminergic neurons partly expressing dopaminergic phenotype: distribution in the brain, development and functional significance. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 38 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi S. N., Vlassenko A. G., Rundle M. M., Snyder A. Z., Mintun M. A., Raichle M. E. (2010). Regional aerobic glycolysis in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 17757–17762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hall G. (2010). Lactate kinetics in human tissues at rest and during exercise Acta. Physiol. 199 499–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. E. (2003). Isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: structure, subcellular localization and metabolic function. J. Exp. Biol. 206(Pt. 12) 2049–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss M. T., Jolivet R., Buck A., Magistretti P. J., Weber B.(2011). In vivo evidence for lactate as a neu-ronal energy source. J. Neurosci. 31 7477–7485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Ola M. S., Berkich D. A., Gardner T. W., Barber A. J., Palmieri F., Hutson S. M., LaNoue K. F. (2007). Energy sources for glutamate neurotransmission in the retina: absence of the aspartate/glutamate carrier produces reliance on glycolysis in glia. J. Neurochem. 101 120–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]