Abstract

The major motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease do not occur until a majority of the dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain SNpc have already died. For this reason, it is critical to identify biomarkers that will allow for the identification of presymptomatic individuals. In this study, we examine the baseline expression of the antioxidant protein Glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTpi) in blood of PD and environmental and age-matched controls and compare it to GSTpi levels following exposure to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), an agent that has been shown to induce oxidative stress. We find that 4 hours of exposure to MPP+, significant increases in GSTpi levels can be observed in the leukocytes of PD patients. No changes were seen in other blood components. This suggests that GSTpi and potentially other members of this and other anti-oxidant families may be viable biomarkers for PD.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive loss of the pigmented dopaminergic (DA) neurons located in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) that results in a reduction in the number of its afferent projections to the striatum. PD motor symptoms first manifest when approximately 60% of the SNpc DA neurons have already died, and striatal dopamine is reduced by approximately 80% (esupp ref 1). Because the progression of cell loss is thought to occur over a somewhat protracted period of time in a defined spatiotemporal manner, the onset of PD symptoms is typically insidious. Biological models suggest that the progression of PD includes a long presymptomatic period, thus there is significant potential for interventions that could slow or even arrest PD at this stage of the disease. However, there is currently no appropriate diagnostic test or biomarker that can identify this presymptomatic population.

One of the proposed etiologies of PD is that an increase in oxidative stress that overwhelms cellular protective mechanisms in the basal ganglia leads to SNpc DA neuron death. This is supported by postmortem studies showing increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and deficient antioxidant capacity in Parkinson’s disease patients [1]. In the brain, the primary scavenger of free radicals is the endogenous antioxidant glutathione. The function of glutathione depends on two enzymes, glutathione peroxidase (GPx, EC 1.11.1.9) and glutathione S-transferase (GST, EC 2.5.1.18), each of which is responsible for the conjugation and removal of both H2O2 and products of lipid and dopamine oxidation (esuppl ref 2). Glutathione S-Transferases (GSTs) are a class of abundant proteins in eukaryotes that appear to function as xenobiotic metabolizing proteins. This class of enzymes may be viewed as a cellular defense against numerous man-made and naturally occurring environmental agents. Structurally, active GST is composed of homodimers containing one of 7 cytosolic subunit classes: alpha, mu, pi, theta, sigma, zeta and omega, 3 microsomal isoforms and 1 mitochondrial form [2]. Functionally, GSTs catalyze the reduction of free radicals by adding glutathione to electrophiles within any number of chemical structures including numerous by-products of oxidative stress, thereby rendering them more soluble and facilitating their elimination from the cell.

In the basal ganglia, a double immunofluorescence study has shown that GSTpi is present in the DA neurons of the SNpc and that changes in its expression mediates sensitivity to MPTP [3] and rotenone [4]; thus any change in its activity may influence the ability of these neurons to handle oxidative stress. In addition to GSTpi’s ability to bind and detoxify electrophiles, the C-terminus of this transferase contains a motif that inhibits cJUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) activated signaling, blocking the phosphorylation of cJUN and apoptosis of the cell [5]. In this regard, MPTP induced activation of JNK and c-jun in mice has been shown to be strain dependant, with a sensitive strain showing earlier and more prolonged activation of cJUN and JNK compared to an MPTP- resistant mouse strain [6]. Together, these studies suggest that any change in the activity of GSTpi may underlie the ability of neurons in the SNpc to handle oxidative stress.

Previous studies have reported that GSTpi levels are increased in substantia nigra of PD patients [4, 7], as well as in alpha-synuclein overexpressing neuroblastoma cells [8]. Polymorphisms in GSTpi have been associated with PD in a Drosophila model expressing mutant parkin [9] as well as having been linked to age of PD onset in individuals of Italian or Greek origin with the alpha-synuclein A53T (PARK1) mutation [10]. Furthermore, polymorphisms in GSTpi have been correlated with increased risk of PD after exposure to pesticides [esupp ref 3].

In addition to its expression in brain, GSTpi is expressed in numerous other tissues including blood [esupp ref4]. To determine if measurement of GSTpi in blood has the potential to be a biomarker for PD, we treated blood taken from PD patients and that of unaffected environmentally-matched cohorts (generally the spouse of the PD patient) with 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), an agent that has been shown to induce oxidative stress through blockade of mitochondrial Complex I following its uptake through the dopamine transporter (DAT) [esupp ref 5]. DAT is present in erythrocytes (esupp ref 6) and lymphocytes (esupp ref 7, 8), and thus this tissue has the potential to be affected by MPP+. GSTpi protein levels were measured in whole blood as well as isolated red blood cells (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), and plasma. We found no differences in GSTpi in plasma, whole blood or RBCs. However, we did find a significant change in GSTpi protein levels in the WBCs of PD patients. This suggests that GSTpi and potentially other members of this and other anti-oxidant families may be viable biomarkers for PD.

Methods

Seventeen patients with PD (12 men, age 68± 9.4; 5 women, age 71 ± 10, range 51-81), and seventeen age-matched controls (12 women, age 66 ± 2.7; 5 men, age 66 ± 6.4, range 49-78) took part in the study. PD patients were at least stage II PD on the Hoehn and Yahr scale and were currently taking a levodopa/carbidopa and (with the exception of 1), anti-inflammatory and/or anti-oxidant drugs (See Table 1). The study was performed at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in collaboration with the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, and was approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from each subject after discussing (verbally and in writing) the study. All experiments on human subjects were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

List of drugs currently prescribed to Experimental (E) and Control (C) study subjects

| Age (yrs) | Gender | UPDRS | Hoehn & Yahr | Regular Medications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | 73 | F | 24 (1+3+20) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa pramiprexole Omega 3 |

| E2 | 81 | M | 57 (2+26+29) | 3 | carbidopa-levodopa ropinirole Aspirin |

| E3 | 77 | F | 31 (1+6+24) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa Celecoxib Donepezil |

| E4 | 59 | M | 33 (1+19+13) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa pramiprexole amantadine Ibuprofen |

| E5 | 79 | M | 64 (6+28+30) | 2 | carbidopa, levodopa and entacapone Aspirin |

| E6 | 63 | M | 25 (1+12+12) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa ropinirole rasagiline apomorphine Vitamine E |

| E7 | 63 | M | 27 (0+11+16) | 2 | carbidopa, levodopa and entacapone ropinirole apomorphine Aspirin Ibuprofen Omega 3 |

| E8 | 78 | F | 34 (1+13+20) | 3 | carbidopa-levodopa ropinirole Aspirin |

| E9 | 74 | F | 29 (4+12+13) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa pramiprexole Aspirin |

| E10 | 53 | F | 29 (4+17+8) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa rasagiline Excedrin migraine |

| E11 | 76 | M | 34 (1+13+20) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa pramiprexole Aspirin Vitamin E |

| E12 | 77 | M | 23 (3+5+15) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa pramiprexole |

| E13 | 53 | M | 69(2+20+47) | 2.5 | carbidopa-levodopa Coenzyme Q10 Vitamin E |

| E14 | 72 | M | 64 (2+20+42) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa ropinirole Ibuprofen |

| E15 | 72 | M | 64 (5+26+33) | 4 | carbidopa-levodopa selegiline Conenzyme Q10 |

| E16 | 70 | M | 51 (1+20+30) | 2 | carbidopa-levodopa sertraline Coenzyme Q10 Aspirin |

| E17 | 54 | M | 26 (1+8+17) | 2 | ropinirole |

| C1 | 75 | M | none | ||

| C2 | 78 | F | Aspirin Meloxicam | ||

| C3 | 49 | M | none | ||

| C4 | 59 | F | none | ||

| C5 | 74 | F | none | ||

| C6 | 62 | F | none | ||

| C7 | 65 | F | none | ||

| C8 | 78 | M | aspirin | ||

| C9 | 76 | M | aspirin | ||

| C10 | 52 | M | none | ||

| C11 | 76 | F | nabumetone | ||

| C12 | 74 | F | aspirin | ||

| C13 | 48 | F | Not determined | ||

| C14 | 72 | F | ibuprofen | ||

| C15 | 71 | F | aspirin | ||

| C16 | 69 | F | Aspirin Ibuprofen | ||

| C17 | 54 | F | none |

Drugs in bold are specifically for PD symptoms.

Blood (approximately 30 ml) was collected by venipuncture into heparin or EDTA-treated vacuum tubes. Measured aliquots were taken immediately for untreated, baseline samples and processed for ELISA (GSTpi protein levels in plasma) or western blotting (GSTpi protein levels in whole blood, RBC and WBC)) as described below. The remaining half of each of the blood samples was allowed to warm to 37 °C (physiological temperature) for 30 minutes after which it was treated with either 1 μM MPP+ or 5 μM MPP+ (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or PBS alone. After an additional incubation for 2 or 4 hours at 37 °C, samples were prepared for measurement of GSTpi protein levels.

GSTpi ELISA was performed on blood samples in which components were separated by centrifugation at 2500 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and a second separation was performed at 6000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C to ensure complete removal of platelets. Plasma supernatants were carefully collected and assayed for GSTpi levels using a commercially available assay (KT-121, Kamiya Biomedical Company, Seattle, WA). GSTpi levels in whole blood, erythrocytes and leukocytes were measured by Western blot. Erythrocytes and leukocytes were obtained by separation on a continuous Percoll (GE Healthcare) gradient. Samples were digested by sonification in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % NP-40, 0.25 % sodium deoxycholate) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor tablets (Roche). After incubation for 1 hour at 4 °C, protein concentrations were determined using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and samples stored at -80°C. Either fifteen or fifty micrograms of protein was resolved by 12.5 % SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NB). Membranes were probed with mouse anti-GSTP1 (1:500, 610719, BD Biosciences) and rabbit anti-beta actin (1:1500 or 1:4000, ab8227, Abcam), followed by goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies conjugated to IRDye 800CW and 680, respectively (LI-COR Biosciences). Bands were visualized and quantified with the LI-COR Odyssey system, and GSTP1 levels were normalized to baseline beta-actin expression that served as a loading control.

Results were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test to determine differences of paired comparisons (control and PD from same environment) or for comparison of two independent groups (no attempt to match individual comparisons for environment), respectively. To investigate the effect of MPP+ dosing on GSTpi in the cases and controls, we employed a mixed effects model with auto-regressive correlation structures of order 1.

Results

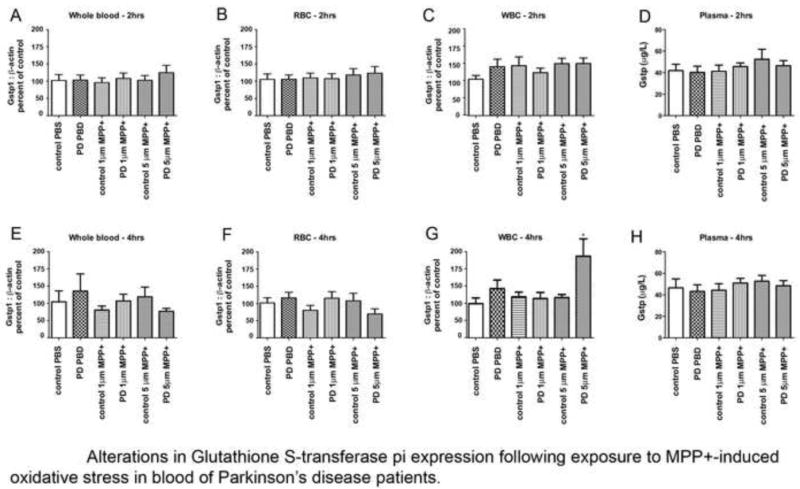

Examination of baseline GSTpi levels in whole blood, erythrocytes or leukocytes of PD patients, compared with their environmentally- and age-matched controls, demonstrated no differences (data not shown). To determine if GSTpi levels of PD patients reacted differently to oxidative stress, either 5 or 10 micromolar MPP+, an agent shown to induce parkinsonism in humans and mice through generation of oxidative stress [eupp ref 5) was added to the blood samples, and GSTpi expression was measured 2 and 4 hours later. We found no differences in GSTpi expression in whole blood at either time (Fig 1A,E). When we separated the blood into component parts, we found no differences in GSTpi expression at 2 or 4 hours after MPP+ in plasma or erythrocytes (Fig 1B,D,F,H). We did, however, find a significant difference in leukocyte GSTpi expression after 4 hours exposure to MPP+ (p≤0.05, Figure 1C,G). All of the patients in this study were all prescribed l-dopa, the precursor to dopamine; a molecule known to produce free radicals (esupp ref 9). Since GSTpi can be induced in response to oxidative stress, we performed a correlation between induced GSTpi levels and l-dopa dosage. We found no correlation between the two factors (r=0.01875).

Figure 1.

Measurement of GSTpi in components of blood following exposure to MPP+. Expression of GSTpi:b-actin ratios in whole blood (A), Red blood cells (B) and Leukocytes (C) 2 hours after exposure to PBS or MPP+ (D). Total GSTpi levels in plasma 2 hours after exposure to PBS and MPP+. Expression of GSTpi:b-actin ratios in whole blood (E), Red blood cells (F) and Leukocytes (G) 4 hours after exposure to PBS or MPP+. (D). Total GSTpi levels in plasma 4 hours after exposure to PBS or MPP+.

Additionally, we also found a “diagnosis x dose” interaction (p≤0.03), where we find that GSTpi levels stays stable in the non-PD group while it significantly increases from baseline in subjects diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Discussion

Parkinson’s disease generally develops in the 6th decade of life, and symptoms appear only after significant damage has already occurred in the basal ganglia. For this reason, the identification and development of biomarkers that predict who is at risk for developing the disease, at a time prior to the occurrence of these pathological events, would potentially have a significant impact on disease progression and management. At this time, only 1 biomarker has been approved for clinical use, DaTscan (Ioflupane I123 Injection, GE HealthCare) that allows for confirmation of a PD diagnosis. However, there have not been any non-genetic polymorphism-based biomarkers verified that identify “at risk” individuals prior to the onset of PD symptomatology, although a recent paper has shown that early PD patients have an increase in auto-antibodies to alpha-synuclein [11]. Here, we report that GSTpi protein is increased in response to oxidative stress in leukocytes of PD patients compared with non-PD environmentally matched controls.

It is generally accepted that alterations in oxidative stress contribute to development of parkinsonism. One of the major components of the anti-oxidant system is glutathione, which acts through association with a glutathione S-transferase to bind and reduce free radicals [2]. In this study, we find that GSTpi levels increase in the blood of PD patients when exposed to MPP+ in using comparisons that examine environmentally-matched subjects as well those that treat each sample as an independent measure. The latter comparison makes the measurement of this enzyme more practical for development of a predictive and relatively simple blood test for identifying individuals susceptible to developing non-familial Parkinson’s disease since in most cases, environmentally-matched samples would not be available.

It is critical to note that unlike the proteomic study examining SN of PD patients [7], we found no difference in baseline levels of GSTpi in the blood of our PD subjects compared with the control group; it was only after a challenge that differences were noted. This suggests that baseline levels of GSTpi, at least as measured in the blood, is not altered in PD, but that regulation either at the mRNA or translation level is different when presented with an oxidative challenge. Second, all of our subjects were currently taking levodopa/carbidopa that could potentially affect the GSTpi response to MPP+, since these are converted to dopamine in the presence of tyrosine hydroxylase present in blood [12], and dopamine has been shown to induce an oxidative response (esupp ref 8,9). However, we found no correlation between the l-dopa dosage and GSTpi induction, so this level of therapeutic dopamine replacement appears to be an unlikely source of the difference. Another potential for increasing the observable differences between PD and control populations would be to measure GSTpi from isolated populations of lymphocytes since these are the cells that express DAT (esupp ref 10) and it is possible that other WBC components such as monocytes could dilute the signal. However, a robust increase in GSTpi when measured from the total lymphocyte population makes the potential for development of a test that can be performed in most clinical labs using standard separation techniques possible.

In conclusion, in a small population of Parkinson’s patients, we find expression of glutathione S-transferase pi protein is increased in leukocytes in response to oxidative stress; an effect not seen in the erythrocytes or plasma. We must however exercise caution since we have examined a small (but representative) group of patients, and a much larger cohort subjects including newly diagnosed, non-medicated patients as well as unaffected but genetically related individuals (to the PD patients) will be needed to validate the use of this enzyme as a biomarker that can predict the development of PD in the general population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NS039006 (to RJS) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhou C, Huang Y, Przedborski S. Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease: a mechanism of pathogenic and therapeutic significance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:93–104. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smeyne M, Boyd J, Raviie Shepherd K, Jiao Y, Pond BB, Hatler M, et al. GSTpi expression mediates dopaminergic neuron sensitivity in experimental parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1977–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610978104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi M, Bradner J, Bammler TK, Eaton DL, Zhang J, Ye Z, et al. Identification of glutathione S-transferase pi as a protein involved in Parkinson disease progression. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:54–65. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang T, Arifoglu P, Ronai Z, Tew KD. Glutathione S-transferase P1-1 (GSTP1-1) inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK1) signaling through interaction with the C terminus. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20999–1003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd JD, Jang H, Shepherd KR, Faherty C, Slack S, Jiao Y, et al. Response to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) differs in mouse strains and reveals a divergence in JNK signaling and COX-2 induction prior to loss of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Brain Res. 2007;1175:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner CJ, Heyny-von Haussen R, Mall G, Wolf S. Proteome analysis of human substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Proteome Sci. 2008;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberio T, Bossi AM, Milli A, Parma E, Gariboldi MB, Tosi G, et al. Proteomic analysis of dopamine and alpha-synuclein interplay in a cellular model of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Febs J. 2010;277:4909–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitworth AJ, Theodore DA, Greene JC, Benes H, Wes PD, Pallanck LJ. Increased glutathione S-transferase activity rescues dopaminergic neuron loss in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8024–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golbe LI, Di Iorio G, Markopoulou K, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos S, Watts RL, et al. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and onset age in alpha-synuclein A53T mutant Parkinson’s disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:254–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanamandra K, Gruden MA, Casaite V, Meskys R, Forsgren L, Morozova-Roche LA. alpha-Synuclein Reactive Antibodies as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Blood Sera of Parkinson’s Disease Patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Josefsson E, Bergquist J, Ekman R, Tarkowski A. Catecholamines are synthesized by mouse lymphocytes and regulate function of these cells by induction of apoptosis. Immunology. 1996;88:140–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.