Background: Conflicting data describe Interleukin 33 as a nuclear factor and ligand for a transmembrane receptor complex.

Results: IL-33 displays multi-compartmental geography, inter-organelle flux and extracellular release from mechanically stressed cells.

Conclusion: IL-33 manifests dynamic subcellular mobility and secretion from living cells upon biomechanical strain.

Significance: IL-33 belongs to a group of factors displaying dual inflammatory and mechano-responsive properties.

Keywords: Cytokine, Fibroblast, Innate Immunity, Interleukin, Protein Secretion, Alarmin, Paracrine

Abstract

Interleukin 33 (IL-33), a member of the Interleukin 1 cytokine family, is implicated in numerous human inflammatory diseases such as asthma, atherosclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Despite its pathophysiologic importance, fundamental questions regarding the basic biology of IL-33 remain. Nuclear localization and lack of an export signal sequence are consistent with the view of IL-33 as a nuclear factor with the ability to repress RNA transcription. However, signaling via the transmembrane receptor ST2 and documented caspase-dependent inactivation have suggested IL-33 is liberated during cellular necrosis to effect paracrine signaling. We determined the subcellular localization of IL-33 and tracked its intracellular mobility and extracellular release. In contrast to published data, IL-33 localized simultaneously to nuclear euchromatin and membrane-bound cytoplasmic vesicles. Fluorescent pulse-chase fate-tracking documented dynamic nucleo-cytoplasmic flux, which was dependent on nuclear pore complex function. In murine fibroblasts in vitro and in vivo, mechanical strain induced IL-33 secretion in the absence of cellular necrosis. These data document IL-33 dynamic inter-organelle trafficking and release during biomechanical overload. As such we recharacterize IL-33 as both an inflammatory as well as mechanically responsive cytokine secreted by living cells.

Introduction

In the innate immune system, numerous features of the Interleukin (IL)2 1 family member IL-33 have suggested this cytokine acts as an “alarmin,”(1) serving as a warning signal between cells at times of injury or cell death. For instance, IL-33 has been shown to be heterochromatin associated, functioning as a transcriptional repressor in living cells (2). In contrast, IL-33 is known to signal via a transmembrane receptor complex of ST2 and Interelukin-1 receptor accessory protein, activating downstream tyrosine kinases and modulating NF-κB activity (3, 4). As IL-33 is cleaved at its receptor binding site by caspase 3 in the context of cellular apoptosis,(5) it has been suggested that IL-33 is released from the nuclear space only during necrosis, whereby it is free to bind its cell surface receptor and affect paracrine inflammatory signaling. The lack of a nuclear export sequence, and like other alarmins such as high-mobility group protein B1 and members of the Interleukin 1 family such as Interleukin-1 α and β, the lack of a canonical secretory signal sequence have been taken as support for the alarmin hypothesis of IL-33. Interestingly however, IL-33 expression is stimulated in the context of non-fatal cellular stretch, particularly in mechano-sensitive cells such as fibroblasts (6). Thus an alterative hypothesis to resolve this inconsistency is that IL-33 is trafficked for release from living cells via non-classical mechanisms upon sublethal biomechanical strain. To address this possibility, we sought to clarify the subcellular location and inter-organelle flux of IL-33 in resting and mechanically stimulated cells, and explored IL-33 release both in vitro and in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Cloning kits and reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cell culture reagents, fluorescent antibodies, probes and dyes were purchased from Invitrogen. Immunohistochemistry reagents were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Antibodies were obtained from AbCam (Cambridge, MA) except for anti-IL-33 antibody Nessy-1 clone (N1) from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and anti-HA antibody (clone 16B12) from Covance (Princeton, NJ). Anti-IL-33 Elisa was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences. Design and characterization of our anti-IL-33 antibody was previously described (6). Lentiviral plasmids, packaging cells and transfection reagents were purchased from System Biosciences (Mountain View, CA). General laboratory chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cloning and Plasmids

Full-length human IL-33 was obtained via PCR from a cDNA library as described (6). PCR primers contained engineered restriction enzyme sites. Fluoroproteins were similarly subcloned with engineered restriction enzyme sites. HA and tetracysteine tags were engineered into PCR primers with sequences 5′-TGTTGTCCCGGGTGTTGTGCA-3′ and 5′-TACCCTTACGATGTACCGGATTACG-CACTCGACGCA-3′, respectively. pCR-Blunt II Topo vector was used as intermediate vector. Fluoroprotein and epitope tags were cloned at the 5′- or 3′-end of IL-33 in the pCDH-EF1-MCS-T2A-Puro lentiviral vector for cell line creation or in pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP for in vivo gene transfer. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Lentivirus Preparation and Cell Line Creation

Lentiviral constructs were introduced with psPAX and pMD2.G packaging and envelope vectors into 293TN cells using PureFection reagent per manufacturer's protocol. 72 h later, culture media were harvested and lentiviral particles concentrated by ultracentrifugation (if destined for in vivo delivery) or Peg-IT reagent (if destined for cell line creation). Stable cell lines were created by transducing NIH3T3 cells with concentrated lentivirus plus polybrene and subjecting them to subsequent puromycin selection. Expression was confirmed via Western blotting for IL-33 and/or HA as appropriate. For in vivo lentiviral delivery, virus was titered by transducing NIH3T3 cells. MOI was calculated by flow cytometric counting of the percent of cells displaying copGFP reporter fluorescence. Lentivirus was delivered at an MOI of 950–1000.

In Vivo Lentiviral Gene Transfer and Transaortic Constriction Experiments

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with guidelines published in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animals. C57BL/6L male mice between the ages of 8–10 weeks under pentobarbital anesthesia and with ventilator assist were used as described (6). For myocardial gene transfer, ten microliters of lentivirus with polybrene was directly injected into left ventricular myocardial tissue under visualization via thoracotomy. For pulmonary gene transfer, forty microliters of lentivirus with polybrene was instilled into the trachea. Postoperative care was conducted as described (6). On post-operative day seven, mice were either anesthetized with pentobarbital and ventricular or pulmonary tissue harvested or mice underwent transaortic constriction versus sham surgery as described (6). After surgery, mice were maintained in post-operative recovery for 2 h prior to sacrifice and tissue harvest. All tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde prior to 70% ethanol dehydration, paraffin embedding, and sectioning.

Biomechanical Strain

Cells were plated at subconfluence on fibronectin-coated strain dishes as described (6). Cyclic strain was conducted at 1 Hertz, 8% biaxial stretch in serum-free medium supplemented with insulin, transferring, and selenium. Media was collected at end-strain and passed through a 0.2-micron filter. Cellular lysates from independent unstrained samples were collected in RIPA buffer and diluted in an equal volume of serum-free medium. Samples were interrogated via anti-IL-33 ELISA. Optical density was converted to absolute IL-33 concentration via standard curve utilizing recombinant human IL-33 serially diluted in DMEM.

Tetracysteine Pulse-chase Experiments

Stable cell lines expressing a tetracysteine-tagged IL-33 were pulsed with a tetracysteine-avid fluorescein dye and washed with British anti-lewisite in PBS (FlAsH reagent, Invitrogen) per manufacturer's instructions. Cells were either fixed, or allowed a chase period prior to fixation prior to further immunohistochemical processing and microscopy. For cytoskeleton disruption experiments, cells were pre-treated with either latrunculin B (1 μm in DMEM) or nocodazole (5 μm in DMEM) 2 h prior to pulse initiation. For ATP depletion experiments, cells were switched from high-glucose DMEM growth medium to glucose-free DMEM supplemented with 25 mm 2-deoxy-d-glucose and 6 mm sodium azide 2 h prior to pulse initiation.

Histology and Microscopy

For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X. Tissues sections were processed via citrate-buffer antigen retrieval. Samples were then blocked with 10% goat serum and 0.1% Triton-X in PBS, incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, washed, and incubated in AlexaFluor secondary antibodies for one hour at room temperature. Hoescht dye was used for nucleic acid counterstaining. For HA-tag immunofluorescence in tissue sections, the signal was resolved via biotinylated secondary antibody followed by tyrimide amplification prior to fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin tertiary antibody application. For immunohistochemistry of pulmonary tissue sections, samples were processed as above. Mouse-on-mouse and streptavidin-biotin blocking kits were utilized prior to incubation in primary antibody. Samples were imaged via confocal or epifluorescent microscopy as indicated. For epifluorescence, images were captured on an Olympus IX-70 microscope via Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For time-lapse microscopy, images were captured on an Olympus IX-70 microscope with an automated, motorized stage controlled via IP Lab software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). For confocal microscopy, images were captured on a Carl Zeiss LSM-710 microscope via LSM Image Browser (Carl Zeiss, Germany). For tetracysteine-based electron microscopy, cells were grown on fibronectin-coated Aclar membranes (Honeywell International, Canton, MA, USA) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Resorufin derivative treatment and photoconversion of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine were performed as described (7). Standard transmission electron microscopy techniques were then utilized as described (8). All images were post-processed in ImageJ (NIH) and Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with PRISM 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). For two sample comparisons, a two-tailed t test was employed. For time-course experiments, significance was assessed via one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison post-test. All data are expressed as means ± S.E. p values less than 0.05 are considered significant.

RESULTS

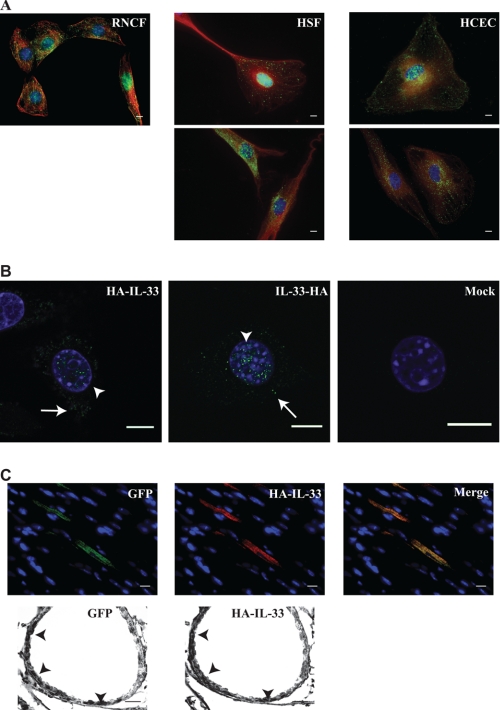

Previously published data suggest that IL-33 fused to a fluoroprotein occupies a nuclear position (2, 9, 10). Similarly in our hands, fibroblasts stably expressing fluoroprotein-tagged IL-33 displayed restricted nuclear localization. When these cells were subjected to cyclic biaxial stretch, nuclear localization of the fusion protein was unaltered (supplemental Fig. S1). Because IL-33 is a 32 kilodalton protein, fusion to a fluoroprotein roughly doubles its molecular weight; it is therefore possible that our current understanding of IL-33 behavior is biased by an artificial restriction of cellular mobility induced by fluoroprotein fusion. Consistent with this supposition, immunofluorescent interrogation of wild type IL-33 in primary endothelial cells and fibroblasts in culture revealed both nuclear and cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 1A). This localization was also seen in a fibroblast cell line stably expressing IL-33 fused to a small epitope tag (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, overexpression of this HA epitope-tagged IL-33 in cardiac ventricular tissue and respiratory epithelium in vivo revealed an identical nucleo-cytoplasmic staining pattern (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that when IL-33 mobility is not restricted by fusion to a fluoroprotein, it simultaneously occupies both nuclear and cytoplasmic positions.

FIGURE 1.

IL-33 simultaneously occupies multiple sub-cellular domains. A, IL-33 displays nuclear and cytoplasmic localization in wild type primary cells. The subcellular localization of IL-33 was interrogated by immunofluorescence epifluorescent microscopy utilizing two different anti-IL-33 antibodies. Rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts (RNCF), human skin fibroblasts (HSF), and human coronary endothelial cells (HCEC) in culture were probed with either a commercially available anti-IL-33 antibody (upper panels) or our previously characterized anti-IL-33 antibody (lower panels). IL-33 signal is pseudocolored green, with anti-tubulin staining (denoting the cytoplasmic space) pseudocolored red. Note our anti-IL-33 antibody does not react with rat IL-33 under immunofluorescence protocols. Scale bars represent 10 μm. B, small epitope tags allow proper modeling of wild type IL-33 localization. In contrast to fluoroprotein-tagged IL-33, an HA tag at either the amino (HA-IL-33) or C (IL-33-HA) terminus permitted nuclear (arrowheads) and cytoplasmic (arrows) localization of stably expressed IL-33 in fibroblasts as seen by confocal microscopy in a pattern mimicking the wild type condition. Scale bars represent 10 μm. C, IL-33 occupies nuclear and cytoplasmic positions in vivo. Lentivirus harboring HA-IL-33 as well as a non-fusion GFP reporter was injected into the left ventricle (upper panels) or instilled into the trachea (lower panels) of anesthetized mice. Upon genomic integration and protein expression, cardiac myocytes revealed strong cytoplasmic HA-IL-33 staining (probed via an anti-HA antibody) in infected cells demarked by GFP expression. Respiratory epithelial cells of terminal bronchioles displayed nuclear and cytoplasmic immunohistochemical staining of HA-IL-33 in cells demarked by GFP expression (arrowheads). Images are representative of 2–3 animals per group and 6–10 microscopic fields per animal. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

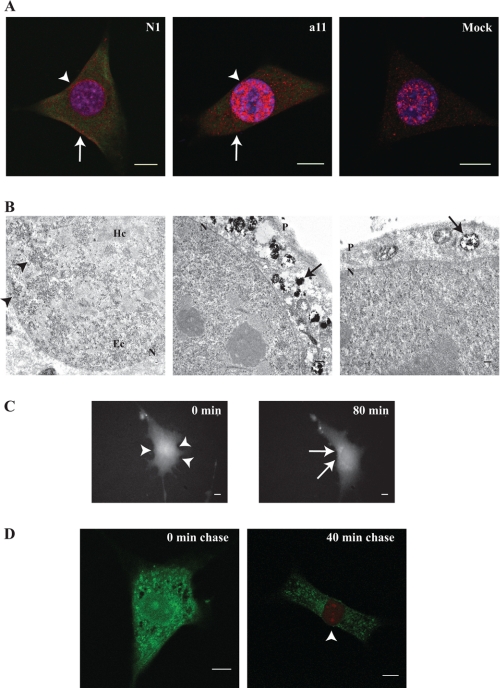

Because IL-33 contains a nuclear localization sequence and chromatin-binding domain in its N terminus,(2) we hypothesized that IL-33 exhibits dynamic inter-organelle flux between the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. Utilizing fluorescent dyes engineered for avidity to a four-cysteine epitope (7) we found that fibroblasts stably expressing tetracysteine-tagged IL-33 (TC-IL-33) exhibited nuclear and cytoplasmic localization mimicking the native expression pattern in primary cells (Fig. 2A). As these tetracysteine-avid dyes are compatible with electron microscopy, we defined the sub-cellular geography of IL-33 in resting fibroblasts expressing TC-IL-33. Nuclear IL-33 molecules were clustered in areas of euchromatin, in distinction to the association of fluoroprotein-tagged IL-33 with heterochromatin as described previously (2). In the cytoplasmic space, amalgams of electron density could be seen within membrane-bound vesicles, explaining the speculated pattern of cytoplasmic IL-33 staining seen by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data suggest that in resting cells, IL-33 associates with nuclear euchromatin and simultaneously resides in the vesicular compartment of the cytoplasm.

FIGURE 2.

IL-33 displays dynamic nucleo-cytoplasmic flux. A, tetracysteine-tagged IL-33 (TC-IL-33) displays nuclear and cytoplasmic localization. A fibroblast cell line stably expressing TC-IL-33 was probed with tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative and one of two anti-IL-33 antibodies (commercially available N1 or a11 raised by our laboratory). Confocal microscopy revealed nuclear (arrowheads) and cytoplasmic (arrows) localization of TC-IL-33 (pseudocolored green), similar to the pattern of wild-type IL-33 staining in mock-transfected cells (anti-IL33 antibody signal pseudocolored red). Note mock-transfected cells did not evidence fluorescein fluorescence. Scale bars represent 10 μm. B, cytoplasmic IL-33 is housed within vesicles. As the tetracysteine-avid resorufin derivative can render 3,3′-diaminobenzidine electron dense,(8) the subcellular localization of TC-IL-33 was interrogated by transmission electron microscopy. Nuclei displayed punctate electron densities (arrowheads) concentrated in areas of euchromatin (Ec). The cytoplasm evidenced electron densities within membrane-bound structures (arrows). P and N denote plasma and nuclear membranes, respectively. Hc indicates heterochromatin. Scale bars represent 1 μm. C, IL-33 displays dynamic nucleo-cytoplasmic flux. Fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 were pulsed with tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative and imaged by time-lapse epifluorescent microscopy. Shown are representative images at 0 and 80 min post-pulse. Over the chase period, a transposition of fluorescence from the nucleus (arrowheads) to the cytoplasmic space (arrows) is evident. A time-lapse movie may be viewed as part of the supplemental materials. Scale bars represent 10 μm. D, newly synthesized IL-33 molecules are nuclear in their localization. Pulse-chase-pulse experiments were performed by exposing fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 to a primary application of tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative followed by secondary resorufin derivative exposure after a variable chase period. By this method, all existent IL-33 molecules at the time of the initial pulse were rendered fluorescein-positive. Molecules synthesized after the primary pulse were non-fluorescent until application of the resorufin derivative at the end of the chase period, allowing differential fluorescence of molecules synthesized at different times. Cells treated with resorufin derivative without a chase period did not evidence red fluorescence in any subcellular compartment. Cells permitted a 40-min chase period evidenced fluorescein fluorescence in the cytoplasm and resorufin fluorescence in the nucleus (arrowhead). Scale bars represent 10 μm.

It was unclear whether the cytoplasmic residence of IL-33 occurs just after molecular synthesis or if newly synthesized molecules are first transported to the nucleus, from where they then efflux into the cytoplasmic space for vesicular packaging. To investigate this, we imaged live cells stably expressing TC-IL-33 via epifluorescent time-lapse microscopy after a pulse of tetracysteine-avid dye. Beginning at 20 min post-pulse and proceeding over the course of 2 h, uniformly stained cells gradually lost their nuclear fluorescence to exhibit a predominantly cytoplasmic pattern, suggesting translocation of nuclear IL-33 to membrane-bound cytoplasmic vesicles over time (Fig. 2C and supplemental video). When these cells were treated with an acidophilic fluorophore at the end of the chase period, colocalization of IL-33 and acidic cytoplasmic granules was noted, suggesting cytoplasmic IL-33 is packaged into secretory vesicles or late endosomes (data not shown).

To confirm that newly synthesized molecules are indeed initially trafficked to the nuclear space, we performed a pulse-chase-pulse experiment whereby fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 were treated with tetracysteine-avid fluorescein dye, rendering all existent TC-IL-33 molecules fluorescent in the green spectral range. Subsequently, the dye was withdrawn and the live cells were allowed a chase period. At the end of the chase, a pulse of tetracysteine-avid resorufin dye was administered, rendering all newly synthesized IL-33 molecules fluorescent in the red spectral range. When no chase period is permitted, all nuclear and cytoplasmic TC-IL-33 molecules appeared fluorescein-bound without evidence of resorufin fluorescence. When a 40-min chase period was permitted, fluorescein fluorescence was relegated to the cytoplasmic space, with resorufin fluorescence evident solely in the nucleus (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data suggest that newly synthesized IL-33 molecules are initially imported into the nucleus for euchromatin association, from where they gradually efflux into the cytoplasmic space to be packaged into secretory vesicles.

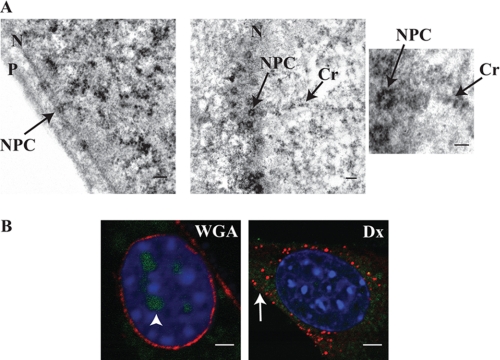

The cellular machinery involved in nuclear efflux of IL-33 was suggested by the finding that increasing the molecular weight of IL-33 via fluoroprotein fusion restricted its localization to the nucleus. As nuclear pore complexes are known to be unbiased in their transport of proteins with molecular weight under 40 kilodaltons (11). IL-33 may utilize the pore complex as a means of inter-organelle transit. To investigate this possible relationship between the nuclear pore complex and IL-33, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy was performed. On nuclear membrane cross-section, electron densities of TC-IL-33 highlighted the nuclear pore complexes. When nuclear pores were sectioned en face, IL-33 molecules could be seen within the central core of the complex itself (Fig. 3A). To document the functional necessity of pore complexes for IL-33 nuclear efflux, we inhibited pore complex molecular transport via wheat germ agglutinin microinjection prior to tetracysteine-avid dye pulse-chase. After a 60 min chase period, control cells revealed the expected loss of nuclear fluorescence and retained a spiculated cytoplasmic fluorescence, consistent with trans-organelle movement of IL-33 from nucleus to cytoplasmic vesicles. However, in wheat germ agglutinin-injected cells, nuclear efflux of TC-IL-33 was abrogated, documented by retention of labeled IL-33 in the nucleus (Fig. 3B). These data suggest IL-33 utilizes the nuclear pore complex in its gradual efflux from the nuclear to cytoplasmic vesicular space in resting cells.

FIGURE 3.

Nucleo-cytoplasmic shift of IL-33 is dependent on the nuclear pore complex. A, IL-33 localizes to nuclear pore complexes. High-magnification transmission electron microscopy of fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 exposed to the tetracysteine-avid resorufin-derivative displayed electron densities highlighting nuclear pore complexes (NPC). The left panel shows the complex in cross section. The middle panel depicts the complex en face whereby IL-33 molecules can be seen within the pore channel itself (enlarged in right panel). In these images, IL-33 can also be seen localizing to a chromatin strand (Cr). P and N denote plasma and nuclear membranes respectively. Scale bars represent 1 μm. B, normal nuclear pore complex function is obligatory for nuclear efflux of IL-33. Fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 were microinjected with either Texas-red conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) to block nuclear pore molecular transit or Texas-red conjugated dextran (Dx) as control. Cells were then treated with the tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative and allowed a 60-min chase period. In the left panel, Texas-red wheat germ agglutinin can be seen binding the plasma and nuclear membranes (pseudocolored red). Clear retention of nuclear fluorescein-labeled IL-33 can be seen (pseudocolored green, arrowhead). In contrast, control cells injected with Texas-red dextran (right panel) evidence efflux of IL-33 from the nucleus into the cytoplasm (arrow). Scale bars represent 5 μm.

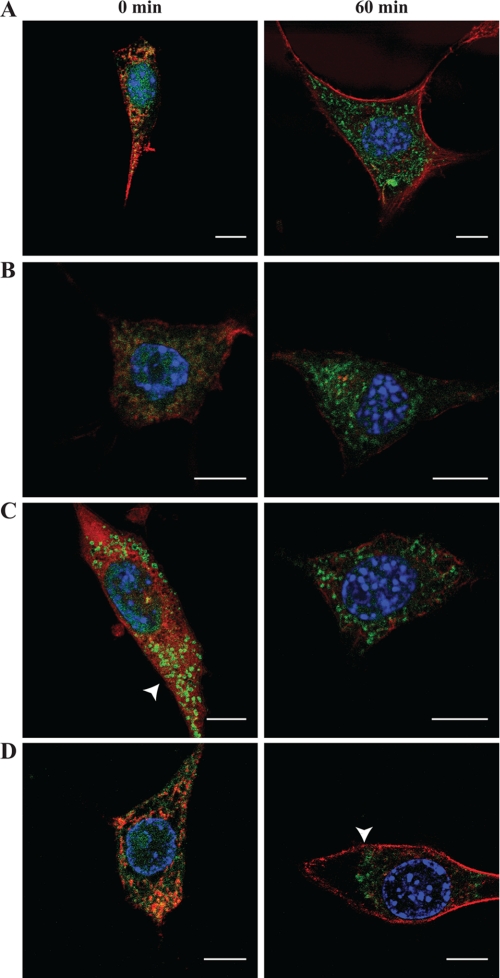

To better understand possible mechanisms underlying the observed nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of IL-33, pulse-chase experiments were conducted in the context of cytoskeletal disruption or under conditions of cellular ATP depletion. When cells stably expressing TC-IL-33 were pretreated with latrunculin B (to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton) prior to tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative pulse-chase, the pattern and timing of nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of IL-33 was similar to control (Fig. 4B). However, when similar experiments were conducted in the presence of nocodazole (to disrupt the microtubule network), cytoplasmic vesicular IL-33 localization was seen at time 0 (immediately after tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative pulse), suggesting that an intact microtubule network retards nuclear efflux of IL-33 (Fig. 4C). When pulse-chase experiments were conducted in under glucose-free conductions and in the presence of sodium azide (to poison mitochondrial ATP production), cytoplasmic vesicular IL-33 staining was seen at end-chase, but the vesicles appeared perinuclear in their location, rather than distributed throughout the cytoplasm as was seen in controls. This observation may suggest that cytoplasmic distribution of vesicular IL-33 may be an ATP-dependent process (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these findings suggest that the kinetics of IL-33 nucleo-cytoplasmic flux is affected by the microtubule network, and ATP is required for normal cytoplasmic transit.

FIGURE 4.

IL-33 translocation depends on an intact microtubule network, and is ATP dependent. A–C, kinetics of IL-33 nucleo-cytoplasmic flux is enhanced upon microtubule disruption. A fibroblast cell line stably expressing TC-IL-33 was pulsed with tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative and allowed a chase period of 0 or 60 min (left and right panels, respectively) under variable conditions of chemical cytoskeletal disruption. A denotes control condition. B depicts experiments conducted in the presence of latrunculin B, to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton. C depicts experiments conducted in the presence of nocodazole, to disrupt the microtubule network. Under conditions of microtubule disruption, cytoplasmic vesicular IL-33 can be seen in the absence of a chase period (arrowhead). D, cytoplasmic transit of vesicular IL-33 is ATP dependent. Tetracysteine-avid fluorescein derivative pulse-chase was conducted under conditions of cellular ATP depletion (glucose free DMEM supplemented with 2-deoxy-d-glucose and 6 mm sodium azide). At the end of a 60-min chase period, punctate fluorescein staining can be seen relegated to a perinuclear position (arrowhead) rather than distributed throughout the cytoplasm as is seen in the control condition (panel A). Fluorescein staining is depicted in green. Phalloidin-based actin (latrunculin and ATP-depletion experiments) or anti-tubulin (nocodazole experiments) staining is depicted in red. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

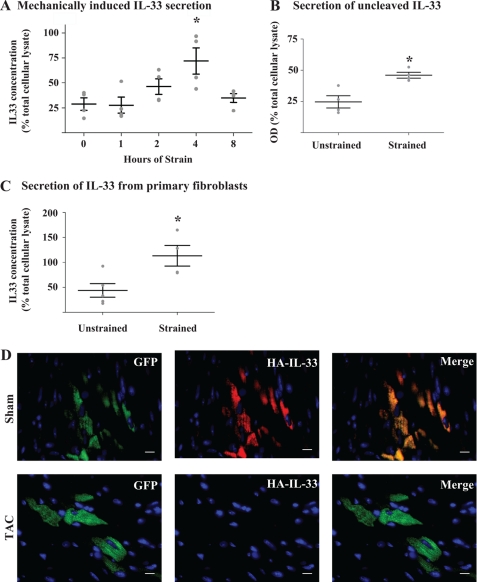

The observed localization of IL-33 to cytoplasmic vesicles, and IL-33's known up-regulation in the context of sublethal biomechanical strain (6) ideally positions this cytokine for release from mechanically stressed cells whereby it could carry out its extracellular functions as a danger signal to neighboring cells without the need for cellular necrosis. To investigate this possibility, fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 were subjected to cyclic biaxial stretch for pre-specified time periods. Over the first 4 h of stimulus, a gradual and significant increase in extracellular IL-33 concentration could be detected. A subsequent decline in the extracellular concentration of IL-33 by 8 h of strain suggested rapid degradation of the protein when it is removed from its intracellular locale (Fig. 5A). Given that fragmentation of IL-33 by proteases is a known phenomenon (5, 12) we constructed a fluorescent immunoassay which simultaneously interrogated the N and C termini of TC-IL-33 to ascertain if the full-length protein is released in the context of mechanical deformation. By this method, after 4 h of cyclic biaxial strain, an increase in extracellular IL-33 concentration was detected in comparison to unstrained control (Fig. 5B), suggesting IL-33 was indeed secreted as a fully intact molecule. To confirm that the application of mechanical deformation was not causing cell loss or death, we verified cellular viability by assessing cell density immediately before, immediately after, and 1 day after the application of 4 h of biomechanical strain, and by assessing membrane-impermeant nucleic acid dye uptake and propidium idodide uptake after the application of 4 h of cyclic strain. Preservation of cellular viability was revealed by all three methods (p value non-significant versus control, data not shown). Together these data document the time-dependent release of uncleaved, full-length IL-33 from living cells under conditions of sublethal biomechanical strain.

FIGURE 5.

Biomechanical strain induces IL-33 secretion from living cells. A, biomechanical strain induces IL-33 secretion. Fibroblasts stably expressing TC-IL-33 were subjected to 1 Hz cyclic 8% biaxial stretch for the number of hours indicated. Extracellular media was assayed via ELISA, and raw optical density values converted to IL-33 concentration via a standard curve followed by normalization to IL-33 in total cellular lysate. At 4 h, a 3.9-fold increase in optical density was measured (p = 0.012 by ANOVA; *, p < 0.01 for 0 versus 4 h by Bonferroni post-test; n = 4 per time point; whiskers represent mean and S.E.). B, IL-33 is released in full-length form. TC-IL-33 expressing cells were subjected to cyclic biaxial stretch for 4 h or left unstrained as control. Culture media was sampled, and TC-IL-33 was captured in a microplate coated with an anti-C-terminal IL-33 antibody. N-terminal tetracysteine fluorescence was induced by exposure to resorufin derivative dye. Raw optical density was normalized to the signal from total cellular lysate. A 1.8-fold increase in fluorescence was noted under conditions of strain compared with control (*, p = 0.008; n = 4 per condition; whiskers represent mean and S.E.). C, IL-33 is released from primary cells upon application of mechanical strain. Primary human skin fibroblasts were subjected to cyclic biaxial stretch for 4 h or left unstrained as control. Extracellular media was assayed via ELISA, and raw optical density values converted to IL-33 concentration via a standard curve followed by normalization to IL-33 in total cellular lysate. A 3.0-fold increase in optical density was noted in the context of strain (*, p = 0.02, n = 4–5 per condition; whiskers represent mean and S.E.). D, IL-33 is lost from cells subjected to biomechanical overload in vivo. Lentiviral particles housing HA-IL-33 and a non-fusion GFP reporter were injected into the left ventricle of anesthetized mice. Seven days later, mice underwent sham surgery (upper panels) or 2-h transaortic constriction (TAC, lower panels) to induce acute pressure overload of the left ventricle. Cardiac sections of sham hearts revealed strong HA-IL-33 staining (probed via an anti-HA antibody) in infected cells demarked by GFP expression. In hearts subjected to TAC, HA-IL-33 immunofluorescence was absent from GFP positive cells. Images are representative of 2–3 animals per group and 6–10 microscopic fields per animal. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

We verified that the phenomenon of IL-33 release from living, mechanically stressed cells was not a feature of cell lines but also a property of primary cells in vitro and in vivo. Primary human skin fibroblasts in culture subjected to cyclic biaxial strain secreted IL-33 into the extracellular space measurable after 4 h of stimulus (Fig. 5C). To extend this finding of IL-33 release to in vivo conditions, mice co-expressing HA-tagged IL-33 and a non-fusion GFP reporter in myocardial tissue via viral gene transfer were subjected to acute transaortic constriction, which induces acute pressure overload of the left ventricle and causes an abrupt mechanical stress at the cellular level. Immunofluorescent analysis of tissue sections documented co-localization of the HA and GFP signals in sham-operated hearts. In hearts subjected to 2 h of pressure overload however, HA-IL-33 was absent from GFP-positive cells, suggesting the release of IL-33 from healthy ventricular myocytes when subjected to mechanical stress (Fig. 5D). These data therefore document the secretion of IL-33 from living cells subjected to acute biomechanical strain both in culture and in vivo.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we describe IL-33 as a multi-organelle protein released from mechanically stressed cells. Fluorescent molecular fate-tracking revealed that newly synthesized molecules are initially shuttled into the nucleus to associate with euchromatin, from where IL-33 utilizes the nuclear pore complex to transit into the cytoplasmic space and reside in membrane-bound vesicles.

Euchromatic localization of IL-33 is consistent with published data suggesting IL-33 may serve as a repressor of transcription (2). Although gene silencing is generally associated with facultative or constitutive heterochromatin, evidence suggests that expression of genes within transcriptionally active euchromatin may be modulated by various factors (e.g. protein-based transcriptional modifiers). Whether IL-33 acts as an “insulator” protein, what its binding partners may be, and what its precise function is within euchromatic regions of the nucleus remains to be investigated (13).

The evidence for nucleo-cytoplasmic flux of IL-33 and the protein's residence in cytoplasmic vesicles ideally positions IL-33 for release in response to physical cellular strain. Consistent with this notion, we documented secretion of uncleaved IL-33 from living cells upon the application of biomechanical stress.

The finding that microtubule disruption enhances the kinetics of IL-33 efflux was surprising. Traditionally, an interaction between microtubules and nuclear pore complexes has been studied in the context of non-canoncial nuclear import (14). Whether and in precisely what fashion nuclear pore complexes and the perinuclear microtubule network interact with IL-33 to modulate efflux kinetics remains to be explored in more detail.

The current understanding of IL-33 biology classifies this molecule as a heterochromatin-associated nuclear transcription factor (2). Because the receptor for IL-33 exists as a transmembrane protein complex, and given IL-33 is cleaved in its receptor-binding domain during apoptosis by caspase 3, it has been suggested that IL-33 is liberated only upon cellular necrosis (5). IL-33 has therefore been grouped with Interleukin-1 beta and High-mobility group protein B1 as an “alarmin.” The data presented here articulates a behavior of IL-33 in living biomechanically responsive cells both at rest and under conditions of physical deformation. Therefore IL-33 may be recharacterized as not only an inflammatory cytokine, but also a mechano-sensitive paracrine factor. Based on this, we propose functional grouping of IL-33 with Interleukin-1 alpha, which exhibits similar properties as an inflammatory and stress-responsive factor (15). In aggregate then, these molecules comprise a novel class of cytokines which not only function as signals in an activated innate immune system but also respond to mechanical stimuli via rapid secretion from structural and supporting cells of physically stressed mammalian tissues.

It is possible that IL-33 behaves differently, with differing subcellular localization and secretory characteristics, depending on the cell type and stimulus applied. Data published to date has focused on cells of the innate immune system, particularly mast cells, basophils, and other granulocytes. Our seemingly contradictory data in fibroblasts may reflect the specific conditions of a physical stimulus on a mechano-sensitive cell type.

Furthermore, although in vitro strain experiments are relatively pure in the sense that the controlled stimulus is exclusively physical in nature, it has been shown that cardiac pressure overload results not only in mechanical strain on cardiac cells, but also activates numerous inflammatory cytokine loops such as those involving interleukin-18 (16), interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 (17), tumor necrosis factor α,(18) and Toll-like receptor 4,(19) as well as numerous hormonal systems (20). Whether the observed release of IL-33 from living ventricular cells in vivo represents a correlate to the in vitro mechanical strain condition or is more attributable to these paracrine systems is unclear. In our system, the short duration (2 h) of transaortic constriction needed to elicit IL-33 release would suggest that mechanical stimulus rather than paracrine systems involved in cardiac hypertrophy are at play.

In conclusion, while IL-33 is typically regarded as an inflammatory cytokine with extracellular function prompted by necrosis-mediated release, we recharacterize IL-33 as a mechanically responsive molecule secreted from living cells subjected to biomechanical overload and place it within a restricted class of such interleukins with active in both inflammatory and biomechanically stressed conditions.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by Grants HL092930 (to R. T. L.) and T32HL007208 (to R. K.) from the NHLBI, National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the Massachusetts General Hospital Division of Cardiology (to R. K.) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF Grant J3004-B18) (to S. D.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and video.

- IL

- interleukin

- TC-IL-33

- N-terminally tetracysteine-tagged IL-33

- HA

- hemagglutinin epitope tag

- RNCF

- rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts

- HSF

- human skin fibroblasts

- HCEC

- human coronary endothelial cells

- N1

- anti-IL-33 antibody (Nessy-1 clone)

- a11

- anti-IL-33 antibody (a11 clone)

- Ec

- euchromatin

- Hc

- heterochromatin

- Cr

- chromatin

- NPC

- nuclear pore complex

- Dx

- dextran

- WGA

- wheat germ agglutinin

- TAC

- transaortic constriction.

REFERENCES

- 1. Haraldsen G., Balogh J., Pollheimer J., Sponheim J., Küchler A. M. (2009) Interleukin-33 - cytokine of dual function or novel alarmin? Trends Immunol. 30, 227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carriere V., Roussel L., Ortega N., Lacorre D. A., Americh L., Aguilar L., Bouche G., Girard J. P. (2007) IL-33, the IL-1-like cytokine ligand for ST2 receptor, is a chromatin-associated nuclear factor in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 282–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lingel A., Weiss T. M., Niebuhr M., Pan B., Appleton B. A., Wiesmann C., Bazan J. F., Fairbrother W. J. (2009) Structure of IL-33 and its interaction with the ST2 and IL-1RAcP receptors–insight into heterotrimeric IL-1 signaling complexes. Structure 17, 1398–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmitz J., Owyang A., Oldham E., Song Y., Murphy E., McClanahan T. K., Zurawski G., Moshrefi M., Qin J., Li X., Gorman D. M., Bazan J. F., Kastelein R. A. (2005) IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity 23, 479–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cayrol C., Girard J. P. (2009) The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is inactivated after maturation by caspase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9021–9026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanada S., Hakuno D., Higgins L. J., Schreiter E. R., McKenzie A. N., Lee R. T. (2007) IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1538–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffin B. A., Adams S. R., Tsien R. Y. (1998) Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science 281, 269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaietta G., Deerinck T. J., Adams S. R., Bouwer J., Tour O., Laird D. W., Sosinsky G. E., Tsien R. Y., Ellisman M. H. (2002) Multicolor and electron microscopic imaging of connexin trafficking. Science 296, 503–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moussion C., Ortega N., Girard J. P. (2008) The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel 'alarmin'? PLoS One 3, e3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Küchler A. M., Pollheimer J., Balogh J., Sponheim J., Manley L., Sorensen D. R., De Angelis P. M., Scott H., Haraldsen G. (2008) Nuclear interleukin-33 is generally expressed in resting endothelium but rapidly lost upon angiogenic or proinflammatory activation. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 1229–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weis K. (2003) Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112, 441–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hayakawa M., Hayakawa H., Matsuyama Y., Tamemoto H., Okazaki H., Tominaga S. (2009) Mature interleukin-33 is produced by calpain-mediated cleavage in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 387, 218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vogelmann J., Valeri A., Guillou E., Cuvier O., Nollmann M. (2011) Roles of chromatin insulator proteins in higher-order chromatin organization and transcription regulation. Nucleus 2, 358–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wagstaff K. M., Jans D. A. (2009) Importins and beyond: non-conventional nuclear transport mechanisms. Traffic 10, 1188–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee R. T., Briggs W. H., Cheng G. C., Rossiter H. B., Libby P., Kupper T. (1997) Mechanical deformation promotes secretion of IL-1α and IL-1 receptor antagonist. J. Immunol. 159, 5084–5088 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colston J. T., Boylston W. H., Feldman M. D., Jenkinson C. P., de la Rosa S. D., Barton A., Trevino R. J., Freeman G. L., Chandrasekar B. (2007) Interleukin-18 knockout mice display maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354, 552–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szabo-Fresnais N., Lefebvre F., Germain A., Fischmeister R., Pomérance M. (2010) A new regulation of IL-6 production in adult cardiomyocytes by β-adrenergic and IL-1β receptors and induction of cellular hypertrophy by IL-6 trans-signaling. Cell. Signal. 22, 1143–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun M., Chen M., Dawood F., Zurawska U., Li J. Y., Parker T., Kassiri Z., Kirshenbaum L. A., Arnold M., Khokha R., Liu P. P. (2007) Tumor necrosis factor-α mediates cardiac remodeling and ventricular dysfunction after pressure overload state. Circulation 115, 1398–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ha T., Li Y., Hua F., Ma J., Gao X., Kelley J., Zhao A., Haddad G. E., Williams D. L., William Browder I., Kao R. L., Li C. (2005) Reduced cardiac hypertrophy in toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice following pressure overload. Cardiovasc. Res. 68, 224–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oparil S. (1985) Pathogenesis of ventricular hypertrophy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 5, 57B–65B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.