Abstract

Although effective alone, opioids are often used in combination with other drugs for relief of moderate to severe pain. Guidelines for acute perioperative pain recommend the use of multimodal therapy for pain management although combinations of opioids are not specifically recommended. Mu opioid drugs include morphine, heroin, fentanyl, methadone, and morphine 6β-glucuronide (M6G). Their mechanism of action is complex, resulting in subtle pharmacological differences among them and with unpredictable differences in their potency, effectiveness, and tolerability among patients. Highly selective mu opioids do not bind to a single receptor. Rather, they interact with a large number of mu receptor subtypes with different activation profiles for the various drugs. Thus, mu-receptor-based drugs are not all the same and it may be possible utilize these differences for enhanced pain control in a clinical setting. These differences among the drugs raise the question of whether combinations might result in better pain relief with fewer side effects. This concept already has been demonstrated between two mu opioids in preclinical studies and clinical trials other combinations are ongoing. This article reviews the current state of knowledge about mu opioid receptor pharmacology, summarizes preclinical evidence for synergy from opioid combinations, and highlights the complex nature of the mu opioid receptor pharmacology.

Keywords: analgesia, combinations, mu receptor, opioid, synergy, MOR-1, morphine

INTRODUCTION

Opioids are often combined with another drug for relief of acute and chronic pain. Indeed, guidelines for acute perioperative pain recommend the use of multimodal therapy for pain management, although these do not include specific recommendations for combinations of opioids [1]. Typical combinations include an opioid plus a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen or more recently other drugs such as ketamine, clonidine or ketorolac. Unfortunately, at this time it is not possible to accurately predict the optimal combination in a specific patient. However, in clinical practice patients being treated with a long-acting opioid often utilize a different opioid for rescue analgesia [2,3].

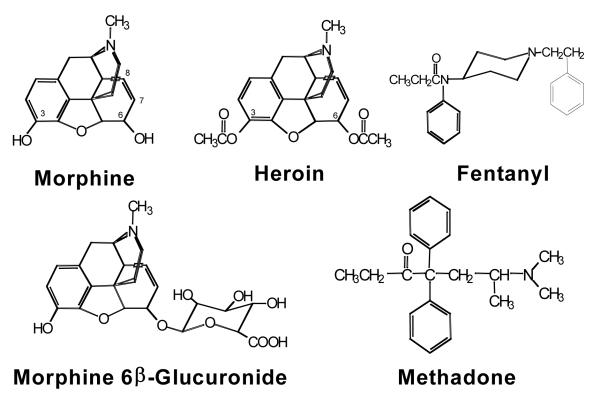

There are three major families of opioid receptors, including mu, kappa, and delta. Most clinically useful opioid analgesics exert their pharmacological actions through mu receptors, with some also having kappa activity [4]. Mu opioids are defined by their selectivity for mu opioid binding sites in brain and for the cloned mu opioid receptor (MOR-1), as opposed to the delta (DOR-1) or kappa1 (KOR-1) receptors [4]. A large number of mu-selective opioid drugs have been developed, with the prototypical mu opioid, morphine, being used for centuries. Morphine, heroin, fentanyl, methadone, and morphine 6β-glucuronide (M6G) are among the more common mu opioids (Figure 1). Although originally thought to be a pharmacologically homogenous group of drugs, these agents demonstrate subtle clinical differences in their pharmacological effects in patients not readily demonstrated in animal models. For instance, the potency and effectiveness of different mu opioid analgesics, as well as their side effects, can vary unpredictably among patients, requiring individualization of treatment. Clinically, patients show incomplete cross tolerance when switched from one mu opioid analgesic to another [4]. Thus, not all mu opioid drugs are the same, raising the question of whether there is a mechanistic rationale for using combinations of opioids to improve pain relief.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of mu opioid analgesics.

This article will review mu opioid receptor pharmacology, summarize evidence for synergistic effects from opioid combinations, and highlight evidence the complex nature of the mu opioid receptor and opioid interactions in preclinical studies that may provide insights into their clinical actions.

MU OPIOID RECEPTOR PHARMACOLOGY

Mu opioid receptors mediate a variety of complex actions including analgesia, respiratory depression, inhibition of gastrointestinal transit, opioid tolerance and dependence, endocrine effects including regulating prolactin, growth hormone, testosterone, and other hormones, and immunological effects [5]. These pharmacological effects can be dissociated by using various antagonists in the laboratory [5].

The variability of opioid responses clinically is well illustrated in comparisons of different genetically defined strains of mice. Morphine is a potent analgesic in the CD-1 mouse, but not in the CXBK mouse [6]. If the different mu opioids acted through a single mu receptor, the effects of other opioid drugs also should be reduced in CXBK mouse. When this was examined experimentally, morphine was active in CD-1, but not CXBK mice while M6G, heroin, and 6-acetylmorphine showed similar analgesic actions in both strains [6]. This dissociation of analgesic sensitivity of the different mu opioids in the CXBK mouse strongly implies the presence of more than one mu opioid mechanism of action.

Selective Blockade of M6G and Heroin Analgesia in Mice

Morphine-6β-glucuronide (M6G) is a metabolite of morphine, binds to mu receptors with an affinity similar to that of morphine, and is a very potent analgesic in both humans and animals. Animal studies suggest that heroin and M6G exert their pharmacological actions through receptor mechanisms distinct from those of morphine. The opioid antagonist, 3-methylnaltrexone, selectively blocks the analgesic effects of heroin and M6G at doses that are inactive against morphine [7]. This was shown in dose-response studies in which 3-methoxynaltrexone shifted the analgesic effective dose (ED50) for heroin and 6-acetylmorphine but not morphine. Thus, 3-methylnaltrexone selectively competes for the receptor through which M6G and heroin act at doses that do not block the receptors responsible for morphine actions.

Incomplete Cross Tolerance to Morphine

Chronic administration of opioids like morphine leads to a progressive decrease in their activity – tolerance. Subjects tolerant to morphine also show tolerance to other mu opioids, but this cross tolerance is not always complete. An excellent example is the conversion of a patient who is tolerant to morphine to methadone. Equianalgesic conversions have been established between these two drugs in naïve patients. However, these relative potencies change in tolerant patients. Indeed, when dealing with a morphine-tolerant patient, the calculated dose of methadone must be reduced by 50% or more to avoid overdosing.

All mu opioids will show cross tolerance to each other, but not always to the same degree. It is possible to develop animal models that illustrate these differences [7]. Animals tolerant to morphine showed no tolerance to M6G, heroin, and 6-acetylmorphine. Similarly, there is incomplete cross tolerance between morphine and methadone [8]. These animal studies were specifically designed to detect subtle differences among the drugs and should not be interpreted as the absence of cross tolerance. Clinical experience clearly shows that cross tolerance exists. Rather the animal models show that the relative levels of tolerance for the drugs may differ - incomplete cross tolerance. Incomplete cross tolerance provides a mechanism to help explain opioid rotation in that the second drug may be used at far lower doses to achieve pain control, thereby minimizing side effects.

ANALGESIC SYNERGY WITH CO-ADMINISTERED OPIOIDS

Combinations of drugs often yield pharmacological effects greater than the sum of the two, in effect, synergy. This has been demonstrated with co-administration of opioids and non-opioids [9,10]. Synergistic analgesia also has been demonstrated clinically with combinations of opioids, together with a reduction in adverse events (AEs) [11,12].

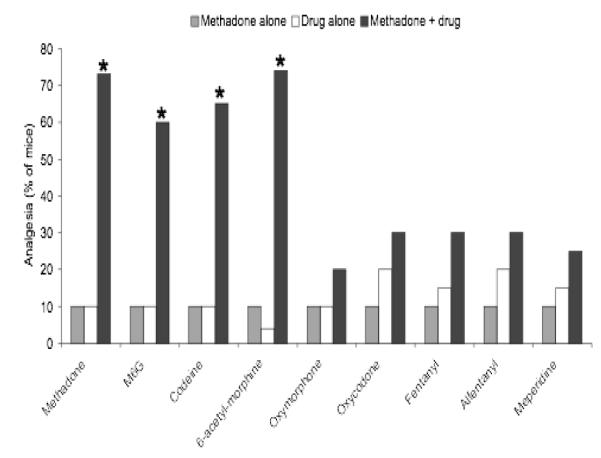

A series of experiments were undertaken to elucidate the synergistic interactions from co-administered opioids [13]. Analgesia was assessed in mice following administration of L-methadone or morphine alone and then combined with L-methadone, morphine, M6G, codeine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, fentanyl, alfentanyl, meperidine, heroin.

Doses of methadone or the indicated drug were chosen to yield similar levels of analgesia when each was given alone [13]. Methadone combined with oxycodone, oxymorphone, fentanyl, alfentanyl, and meperidine demonstrated analgesic effects that were additive (Figure 2). However, methadone combined with morphine, M6G, codeine, and heroin revealed a marked increase in the analgesic effect that was far more than additive, i.e. synergistic.

Figure 2.

Effect of L-methadone and morphine alone and combined with other opioids on analgesia in mice [13]. *P<0.001

Similar observations were seen with morphine. Morphine combined with most of the other drugs yielded additive analgesic effects (Figure 2). However, when morphine was combined with methadone, the combination was synergistic [13]. Interestingly, the synergistic effects between methadone and morphine were limited to the L-isomer, which is the active isomer at mu receptors, as opposed to the D-isomer, which reportedly has NMDA antagonist properties.

The ED50 was determined from dose response curves for methadone and selected other opioids to assess whether the analgesic effects of combinations were additive or synergistic using isobolographic analysis [13]. Based on this analysis, synergy was seen with combinations of methadone with morphine, M6G, codeine, and heroin but not apparent when methadone was combined with fentanyl.

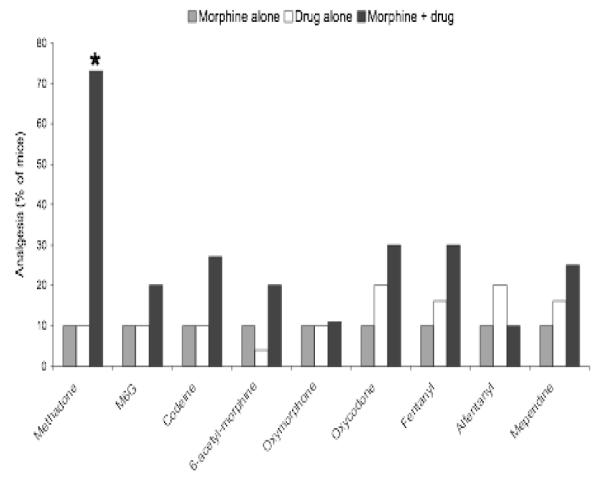

To determine if the synergistic effects were limited to analgesia alone or were applicable to other pharmacologic effects of opioids, the effects of administration of methadone and morphine alone and combined on gastrointestinal transit were evaluated [13]. The results demonstrate synergy between the two with regards to their analgesia, but not for their inhibitory actions on gastrointestinal transit (Figure 3). These results suggest that co-administration of opioids could result in an enhanced, synergistic effect on analgesia without an accompanying increase in side effects.

Figure 3.

Effect of administration of L-methadone and morphine alone and combined on analgesia and gastrointestinal transit in mice [13].

In summary, synergistic analgesia was demonstrated with co-administration of methadone with morphine, M6G, codeine or heroin. In contrast, morphine was only synergistic with methadone. Differences in synergy between drugs indicate the presence of a complex pharmacology and support the concept that mu opioids exert their analgesic effects by activity at different receptor sites. These results also support the rationale for combining opioids for pain management to achieve enhanced efficacy and tolerability.

MU OPIOID RECEPTOR GENETICS AND OPIOID PHARMACOLOGY

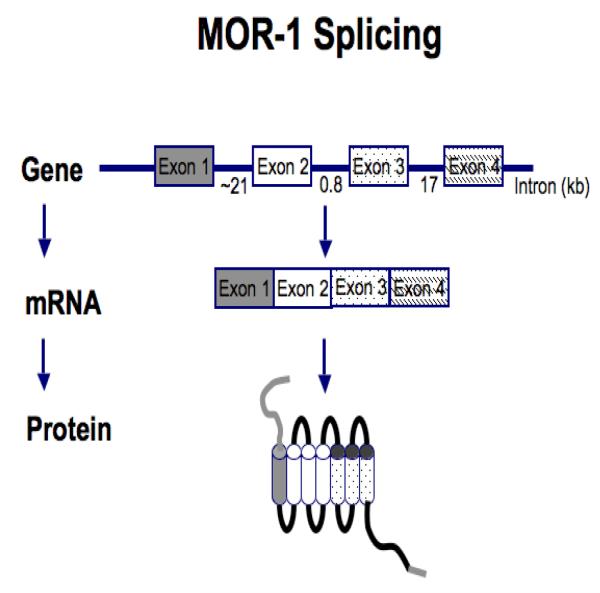

It is difficult to reconcile differences in pharmacological effects among the mu opioid drugs on the basis of the existence of a single mu receptor. In 1993, the mu receptor (MOR-1) was cloned and determined to be a G-protein coupled receptor [14]. However, only a single gene has been associated with MOR-1. Genes are composed of exons – the actual sequences that are included in mature mRNA that is translated into the relevant proteins – and introns, comprising regions of the gene that are spliced out and lost during the generation of mRNA.

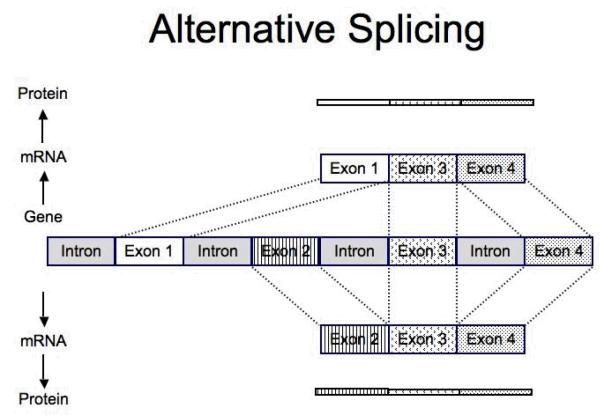

Most genes have multiple exons that are spliced together to create the mRNA that is translated into the protein (Figure 4). Splicing provides the ability of a single gene to generate a wide range of related proteins; some genes contain extremely large numbers of exons that allow extensive splicing [14,15]. Combining different sets of exons within a gene to form different mRNA’s is termed alternative splicing and results in the potential to produce a vast array of proteins [15]. Thus, alternative splicing offers the ability for a single gene to generate many different proteins (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagram of MOR-1 (mu-opioid receptor) splicing and alternative splicing [adapted from reference 14].

Alternative Splicing of the Mouse MOR-1 Receptor

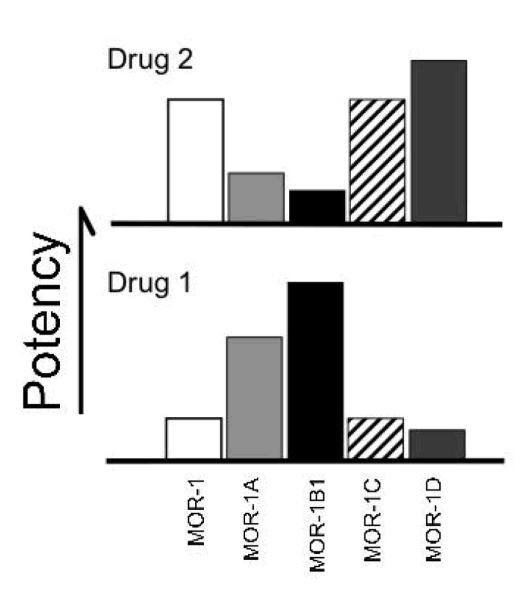

Multiple mu opioid receptors are now recognized, and thus, it is not surprising that different opioids produce distinctly different pharmacological effects. Four exons originally were identified from the original clone of the gene for MOR-1 [15,16]. Approximately 90% of the structure of the receptor is encoded by the first 3 exons, with exon 4 encoding only 12 amino acids at the intracellular C-terminus of the mu opioid receptor. There are a large number of full length splice variants in which these 12 amino acids are replaced with various amino acid sequences based by the replacement of exon 4 with various combinations of other exons. However, the remainder of the receptor is unchanged, which explains why the variants show the same selectivity for mu opioid drugs, because the binding sites within the receptor are identical for all the variants. Subsequent work determined that a more complex array of splice variants existed for MOR-1 [17-21]. Exon 5 produces five different splice variants, and a number of additional exons can be alternatively spliced instead of exon 4, which results in an additional four splice variants of MOR-1.

The presence of multiple mu receptors provides an opportunity to understand why opioid actions vary among different patients [5,14]. Because all full length human mu receptor splice variants have identical binding sites, morphine will bind to all of them. However, the ability of other opioid drugs to activate each of the receptor subtypes may not be the same. Since the overall actions of drugs reflect the summation of their actions at all the subtypes at the same time, the overall profiles of various mu drugs may differ, resulting in subtle differences in their pharmacological actions.

Confocal Microscopy of MOR-1 and MOR-1C in the Spinal Cord

The regulation of the MOR-1 splicing is quite complex. Strong evidence exists that cell specific splicing occurs in which different cells express different splice variants [14]. Confocal microscopy shows that the splice variants MOR-1 and MOR-1C are both located in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord [22]. However, at high power, it becomes clear that most of the cells in the dorsal horn express either MOR-1 or MOR-1C, but not both. This raises the interesting question of how a cell knows to produce one variant and not the other. Ultrastructurally, the splice variants also differ in their localization within the neuron. MOR-1 is located both presynaptically and postsynaptically, whereas MOR-1C is almost exclusively located presynaptically [23]. Thus, splicing influences the location of the receptors within the cell.

Opioid Analgesia in MOR-1 Exon 1 Knockout Mice

Morphine produces analgesia by activating mu opioid receptors encoded with the MOR-1 gene. Although M6G, heroin, and 6-acetyl morphine are mu opioids, evidence suggests that they act through distinct receptor mechanisms [24]. The first suggestion came from antisense mapping studies [25-27] where proteins are lost by selectively targeting mRNA. However, the clearest findings came from knockout mice, in which a portion of the MOR-1 gene is destroyed. In a study of knockout mice lacking exon 1 which therefore have no MOR-1 variants that include exon 1, revealed that they were insensitive to morphine [24]. In contrast, M6G and 6-acetylmorphine continued to elicit analgesia in these mice with potencies only slightly less than in wild-type mice. These results provide genetic evidence for unique receptor sites for M6G and 6-acetylmorphine that differ from those for morphine.

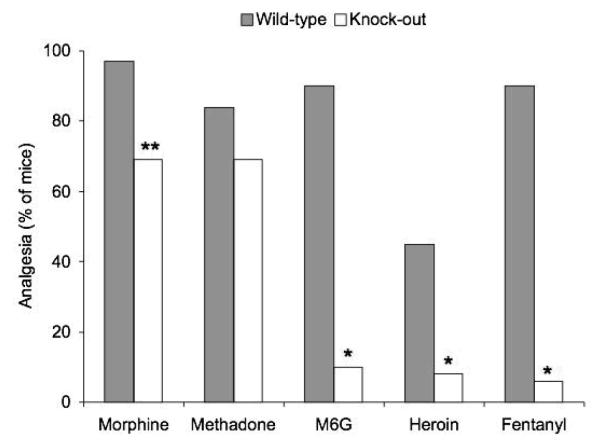

Opioid Analgesia in MOR-1 Exon 11 Knockout Mice

Both morphine and heroin have a high affinity and selectivity for mu receptors, but heroin demonstrates residual analgesia in the exon 1 MOR-1 knockout mice that do not respond to morphine, suggesting different receptor mechanisms for the two drugs. When examining how these exon 1 MOR-1 knockout mice might still respond to heroin and M6G, it became apparent that these animals still expressed a series of MOR-1 splice variants that normally do not contain exon 1. These variants, which are associated with exon 11, have been isolated form mice, humans, and rats. To investigate whether these exon 11-associated variants were involved, the drugs were investigated in a different mouse in which exon 11 was removed, without interfering with exon 1 [16]. Loss of exon 11 produces a very different pharmacological effect than the exon 1 knockout mice. Disruption of exon 11 had a minimal impact on the analgesic effect of either morphine or methadone (Figure 5). In contrast, the analgesic response to heroin, M6G, and fentanyl in exon 11 knockout animals was markedly reduced. This is well illustrated by the various shifts in ED50 for the various drugs (Table 1). These results further support the concept that mu opioids exert different pharmacological actions mediated by variations in receptor interactions.

Figure 5.

Analgesic activity of opioids in wildtype and knockout mice with disrupted exon 11 after administering various opioids [16]. *p<0.0001, **p<0.01

Table 1.

Differences in the analgesic response to various opioids as evidenced by the shift in ED50 in wild-type (WT) and knock-out (KO) mice [16,24].

| Exon-1 KO (mg/kg, s.c.) | Exon-11 KO (mg/kg, s.c.) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | WT | KO | Shift | WT | KO | Shift |

| Morphine | 5.0 | >100 | >20 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| Methadone | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.2 | |||

| M6G | 3.8 | 8.5 | 2.3 | 0.92 | 19.3 | 21 |

| Heroin | 1.2 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 0.58 | 3.2 | 6 |

| Fentanyl | 0.024 | 0.230 | 10 | |||

SUMMARY

The mechanism of action and pharmacology of opioids is complex. Opioids considered to be highly mu-selective still bind to a large number of mu receptor subtypes, with the various opioids producing subtly different pharmacological response based upon their distinct activation profiles of the mu receptor subtypes. Differences in the individual variation in expression of these subtypes have not yet been explored, but they also may play a role in differences in opioid sensitivity. The impact of these differences on the pharmacological effects of opioids may be simplified using an analogy. The differences between the pharmacological effects of opioids may be compared to the differences heard in a piece of music by that occurs by simply changing the volume of various instruments. The tune remains the same and the similarities in the piece of music are heard, but the differences in the sound also are readily appreciated. Thus, while different mu opioids bind to all mu receptors and produce similar pharmacological effects, subtle changes in their relative receptor activation may explain subtle differences in their pharmacology (Figure 6). This may help explain some of the interpatient variability in the pharmacological response to opioids and the incomplete cross tolerance among the mu opioid analgesics. The most important and compelling of the concepts described here is that mu-receptor-based drugs are not all the same and it may be possible to use these differences in a clinical setting. Preclinical and clinical findings suggest different activation profiles for the stimulation of the mu subtypes for many of the drugs. This raises questions about what might occur with combinations of these agents, which is particularly intriguing since combinations have the potential to enhance analgesia with fewer side effects. Clinicians often use more than one drug to relieve pain, i.e., combinations of an opioid with acetaminophen, aspirin or a NSAID so the concept of multimodal analgesia in pain management is recognized and endorsed in pain treatment guidelines. Determining whether combinations of opioids provide efficacy and tolerability advantages compared with either opioid alone is being investigated in clinical trials of patients with acute and chronic pain.

Figure 6.

Subtle changes in receptor activation may explain subtle differences in opioid pharmacology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by grants DA02615, DA06241, and DA07242 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The author would like to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Richard S. Perry, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This paper was from a symposium presentation at the 13th World Congress on Pain, August 2010, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, which was sponsored by QRx Pharma Inc., Bedminster, New Jersey.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1573–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauretti GR, Oliveira GM, Pereira NL. Comparison of sustained-release morphine with sustained-release oxycodone in advanced cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2027–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercadante S, Villari P, Ferrera P, Casuccio A. Addition of a second opioid may improve opioid response in cancer pain: preliminary data. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:762–6. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasternak GW. The pharmacology of mu analgesics: from patients to genes. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:220–31. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis MP, Pasternak . Chapter 1, Opioid receptors and opioid pharmacodynamics. In: Davis MP, Glare PA, Hardy J, Quigley C, editors. Opioids in Cancer Pain. 2nd Edition Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi GC, Brown GP, Leventhal L, Yang K, Pasternak GW. Novel receptor mechanisms for heroin and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia. Neurosci Lett. 1996;216:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GP, Yang K, King MA, Rossi GC, Leventhal L, Chang A, Pasternak GW. 3-Methoxynaltrexone, a selective heroin/morphine-6beta-glucuronide antagonist. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:35–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasternak GW. Incomplete cross tolerance and multiple mu opioid peptide receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01616-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelcer S, Kolesnikov Y, Kovalyshyn I, Pasternak DA, Pasternak GW. Selective potentiation of opioid analgesia by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Brain Res. 2005;1040:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatti A, Sabato E, Di Paolo AR, Mammucari M, Sabato AF. Oxycodone/paracetamol: a low-dose synergic combination useful in different types of pain. Clin Drug Invest. 2010;30(Suppl 2):3–14. doi: 10.2165/1158414-S0-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenthal S, Min K, Marquardt M, Borgeat A. Postoperative intravenous morphine consumption, pain scores, and side effects with perioperative oral controlled-release oxycodone after lumbar discectomy. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:233–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000266451.77524.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamison RN, Raymond SA, Slawsby EA, Nedeljkovic SS, Katz NP. Opioid therapy for chronic noncancer back pain. A randomized prospective study. Spine. 1998;23:2591–600. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolan EA, Tallarida RJ, Pasternak GW. Synergy between mu opioid ligands: evidence for functional interactions among mu opioid receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:557–62. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasternak GW. Opioid pharmacotherapy: from receptor to bedside. In: Inturrisi CE, Nicholson B, Pasternak GW, editors. Dual-Opioid Therapy; International Congress and Symposium Series 271; Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasternak GW. Molecular insights into mu opioid pharmacology: From the clinic to the bench. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(Suppl 10):S3–9. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181c49d2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan YX, Xu J, Xu M, Rossi GC, Matulonis JE, Pasternak GW. Involvement of exon 11-associated variants of the mu opioid receptor MOR-1 in heroin, but not morphine, actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4917–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811586106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasternak DA, Pan L, Xu J, Yu R, Xu MM, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Identification of three new alternatively spliced variants of the rat mu opioid receptor gene: dissociation of affinity and efficacy. J Neurochem. 2004;91:881–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan E, Abbadie C, Chang A, Zuckerman A, Rossi G, Pasternak GW. Identification and characterization of three new alternatively spliced mu-opioid receptor isoforms. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:396–403. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan E, Chang A, Mahurter L, Rossi G, Pasternak GW. Isolation and expression of a novel alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor isoform, MOR-1F. FEBS Lett. 2000;466:337–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan YX, Xu J, Mahurter L, Bolan E, Xu M, Pasternak GW. Generation of the mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) protein by three new splice variants of the Oprm gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14084–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241296098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan E, Moskowitz HS, Xu M, Pasternak GW. Identification of four novel exon 5 splice variants of the mouse mu-opioid receptor gene: functional consequences of C-terminal splicing. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:866–75. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbadie C, Gultekin SH, Pasternak GW. Immunohistochemical localization of the carboxy terminus of the novel mu opioid receptor splice variant MOR-1C within the human spinal cord. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1953–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbadie C, Pasternak GW, Aicher SA. Presynaptic localization of the carboxy-terminus epitopes of the mu opioid receptor splice variants MOR-1C and MOR-1D in the superficial laminae of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2001;106:833–42. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuller AG, King MA, Zhang J, Bolan E, Pan YX, Morgan DJ, Chang A, Czick ME, Unterwald EM, Pasternak GW, Pintar JE. Retention of heroin and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia in a new line of mice lacking exon 1 of MOR-1. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:151–6. doi: 10.1038/5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossi G, Pan YX, Cheng J, Pasternak GW. Blockade of morphine analgesia by an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide against the mu receptor. Life Sci. 1994;54:PL375–9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi GC, Standifer KM, Pasternak GW. Differential blockade of morphine and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides directed against MOR-1 and G-protein alpha subunits in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1995;198:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11977-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi GC, Pan YX, Brown GP, Pasternak GW. Antisense mapping the MOR-1 opioid receptor: evidence for alternative splicing and a novel morphine-6 beta-glucuronide receptor. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:192–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00757-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]