Abstract

Knowledge of the binding repertoires and specificities of HLA-DQ molecules is somewhat limited and contradictory, partly because of the scarcity of reports addressing some of the most common molecules and possibly because of the diversity of the techniques used. In this paper, we report the development of high-throughput binding assays for the six most common DQ molecules in the general worldwide population. Using comprehensive panels of single substitution analogs of specific ligands, we derived detailed binding motifs for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, and DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501 and more detailed motifs for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201, DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, previously characterized on the basis of sets of eluted ligands and/or limited sets of substituted peptides. In contrast to what has previously been observed for DR and DP molecules, DQ motifs were generally less clearly defined in terms of chemical specificity and, strikingly, had little overlap with each other. However, testing a panel of peptides spanning a set of Phleum pratense Ags, and panels of known DQ epitopes, revealed a surprisingly significant and substantial overlap in the repertoire of peptides bound by these DQ molecules. Although the mechanism underlying these apparently contradictory findings is not clear, it likely reflects the peculiar mode of interaction between DQ (and not DR or DP) molecules and their peptide ligands. Because the DQ molecules studied are found in >85% of the general human population, these findings have important implications for epitope identification studies and monitoring of DQ-restricted immune responses.

T cells recognize MHC–epitope complexes (1–4).MHC molecules are extremely polymorphic, with several thousand of different variants known in humans (5–8). Much of the observed polymorphism is concentrated in residues experimentally known or modeled to line the peptide-binding groove or form the specific pockets that engage the amino acid side chains of the peptide ligand.

Addressing multiple MHC-binding specificities is therefore required to allow coverage of the general human population. This issue of population coverage is further complicated by the fact that different MHC types are expressed at dramatically different frequencies in different ethnicities. Thus, without careful consideration, an epitope set could result in ethnically biased population coverage and decreased applicability for any diagnostic, immunoprophylactic, or immunotherapeutic applications. One means of circumventing these problems relies on the selection of epitopes restricted by multiple MHC types. Alternatively, epitope sets representing the most common molecules present in each patient population will have to be selected and studied.

In the case of HLA class I, previous studies have demonstrated the existence of MHC supertypes, which define sets of A and B class I molecules associated with largely overlapping peptide-binding repertoires (9–12). In the context of HLA class II, four different loci must be considered: DRB1, DRB3/4/5, DP, and DQ. Several studies have suggested the existence of class II supertypes encompassing several DR and DP specificities that, as with class I supertypes, describe sets of molecules sharing largely overlapping peptide-binding repertoires (13–29). Some epitope and peptide-binding specificity overlap has also been reported in the case of two HLA-DQ molecules (26).

But in comparison, DQ-associated motifs have been less extensively characterized. Indeed, the vast majority of studies characterizing DQ-binding specificity have been targeted at DQ2 (DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201) (26, 30–34) and DQ8 (DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302) (26, 30, 35–37), which have been associated with susceptibility to celiac disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus (38–42). Studies characterizing the peptide-binding specificities of other common DQ molecules have been more limited in both breadth and detail (43–47). Thus, with these limitations, it has not been possible to discern whether a general mode of DQ binding can be defined, as has been done for both DR and DP molecules. That the existing data might not be enough to extrapolate a general DQ supertypic binding specificity is indicated from studies analyzing the structure of DQ molecules and IA molecules (the murine ortholog of DQ) (37, 47–52). These structural studies have shown that in several instances, interactions between amino acid side chains of the peptide ligands and the peptide-binding pockets of the MHC contribute relatively little to the overall binding energy. Instead, binding may, in these cases, be more dependent on peptide backbone–MHC interactions.

In this paper, we report the development of high-throughput binding assays for the six most common HLA-DQ molecules in the general worldwide population. Using these assays on a comprehensive panel of single substitution analogs, we have derived detailed binding motifs for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, and DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501.We have also derived more detailed quantitative motifs for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201, DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, previously characterized on the basis of sets of eluted ligands and/or limited sets of substituted peptides. These six DQ molecules, selected on the basis of their frequency in human populations, were found to have very few similarities in their peptide motifs. This is in contrast to what was previously observed in the case of DR and DP molecules, which share largely overlapping locus-specific peptide motifs. However, testing a panel of peptides spanning a set of Phleum pratense Ags and panels of known DQ epitopes surprisingly revealed a significant and substantial overlap in the repertoire of peptides bound by these DQ molecules.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis

Peptides for screening studies were purchased from Mimotopes (Clayton, Victoria, Australia) and/or A and A (San Diego, CA) as crude material on a small (1 mg) scale. Peptides used as radiolabeled ligands were synthesized on larger scale by A and A and purified (>95%) by reversed-phase HPLC.

MHC purification

MHC molecules were purified from EBV-transformed homozygous cell lines (see Results) by mAb-based affinity chromatography, essentially as described in detail elsewhere (29, 53). Briefly, cells were maintained in vitro by culture in RPMI 1640 medium (Flow Laboratories, McLean, VA), supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), 100 U (100 mg/ml) penicillin-streptomycin solution (Life Technologies), and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Hazelton Biologics, Lenexa, KS). Large-scale cultures were maintained in roller bottles. HLA molecules were purified from cells lysed at a concentration of 108 cells/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), containing 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM PMSF. Lysates were then passed through 0.45 µM filters and cleared of nuclei and debris by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min.

For affinity purification, columns of inactivated Sepharose CL4B and protein A-Sepharose were used as precolumns. HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP molecules were captured by repeated passage of lysates over LB3.1 (anti–HLA-DR),SPV-L3 (anti–HLA-DQ), and B7/21 (anti–HLA-DP) columns. After two to four passages of the lysate, Ab columns were washed with 10-column volumes of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) with 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 2-column volumes of PBS, and 2-column volumes of PBS containing 0.4% (w/v) n-octylglucoside. MHC molecules were then eluted with 50 mM diethylamine in 0.15 M NaCl containing 0.4% (w/v) n-octylglucoside (pH 11.5). A 1/26 volume of 2.0 M Tris (pH 6.8) was added to the eluate to reduce the pH to 8. Eluates were concentrated by centrifugation in Centriprep 30 microconcentrators at 2000 rpm (Amicon, Beverly, MA). Protein purity, concentration, and the effectiveness of depletion steps were monitored by SDS-PAGE and bicinchoninic acid assay.

MHC-peptide binding assays

Assays to quantitatively measure peptide binding to class II MHC molecules are based on the inhibition of binding of a high-affinity radiolabeled peptide to purified MHC molecules. This assay system has been described in detail elsewhere (29, 53, 54) but is briefly described in general terms in this paper. The optimal assay conditions for each DQ molecule tested in the current study are summarized in Results. To measure the capacity of peptide ligands to bind MHC molecules, 0.1–1 nM radiolabeled peptide is coincubated at room temperature or 37°C with 1 µM to 1 nM purified MHC in the presence of a mixture of protease inhibitors (EDTA, pepstatin A, N-ethylmaleimide, 1,10-phenanthroline, PMSF, and Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone). Following a 2- to 4-d incubation, the percentage of MHC-bound radioactivity is determined by capturing MHC–peptide complexes on LB3.1 (DR), L243 (DR), HB180 (DR/DQ/DP), SPV-L3 (DQ), or B7/21 (DP) Ab-coated Optiplates (Packard Instrument, Meriden, CT), and determining bound cpm using the TopCount (Packard Instrument) microscintillation counter. In the case of competitive assays, the concentration of peptide yielding 50% inhibition of the binding of a radiolabeled standard probe peptide is calculated.

The exact concentration of the radiolabeled peptide used as the assay probe is difficult to accurately determine, because the iodination process we use is performed in conditions optimized empirically to achieve the highest sp. act., and very small amounts of peptides are used in the reactions. However, assuming even 100% labeling efficiency, the amount of label is always less than the amount of active MHC. Thus, under the conditions used, where [label] < [MHC] and IC50 ≥ [MHC], the measured IC50 values are reasonable approximations of the true Kd values (55, 56). Because of the range of doses of inhibitor peptides tested, in only certain cases are these approximations not valid. At one extreme are the essentially nonbinding peptides (i.e., those with affinities >30,000 nM), whose affinities are biologically irrelevant, where a Kd value may be determined with a concentration that is <30% of its Kd. At the other extreme, affinity measurements in the <0.5 nM range (seldom encountered) are inherently less accurate and should be interpreted with caution. Each inhibitor peptide is tested under identical conditions, using a fixed amount of radiolabeled peptide and MHC. Thus, although in some cases the measured IC50 values may represent overestimations or underestimations of true Kd values, the use of identical conditions allows defining relative binding values, as in the case of single substitution analogs. Representative binding curves are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. Each competitor peptide is tested at six different concentrations covering a 100,000-fold dose range (30,000, 3,000, 300, 30, 3, and 0.3 nM) in three or more independent experiments. As a positive control, the unlabeled version of the radiolabeled probe is also tested in each experiment. All MHC-peptide binding data generated in the course of the current study will be submitted to the Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (http://www.iedb.org).

Bioinformatic analyses

The peptide-binding repertoire (R) of each MHC molecule (i) was defined as the set of the peptides that bind that molecule with an affinity of ≥1000 nM. The relationship between two molecules has been measured by determining cross-reactivity and repertoire overlap. Cross-reactivity is defined as the fraction of peptides that bind one MHC molecule that also bind a second or (Ri AND Rz)/(Ri) × 100%. Repertoire overlap is defined as the fraction of peptides binding either molecule that bind both (i.e., repertoire overlap = [Ri AND Rz]/[Ri OR Rz] × 100%).

Population coverage was calculated as described previously (57). Gene frequencies for each HLA allele were calculated from population frequencies obtained from DbMHC (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD [58]). Phenotypic frequencies were calculated using the binomial distribution formula: phenotypic frequencies = 1 − (1 − ∑gf)2. To obtain total potential population coverage, no linkage disequilibrium was assumed.

Analysis of the single amino acid substitution binding data were performed essentially as described previously for analysis of positional scanning combinatorial library data (29, 59,60). Briefly, the IC50 nM value of each substituted peptide was standardized relative to the geometric mean IC50 nM value of the wild-type peptide. Relative binding values were then represented in a 20 aa by position matrix. Next, an average (geometric) relative binding affinity (ARB) was calculated for each position, encompassing all 20 possible residues. Finally, for each position, the ratio of the ARB for the entire library to the position-specific ARB was derived. We have denominated this ratio, which describes the factor by which the geometric average binding affinity associated with all 20 residues at a specified position differs from that of the average affinity of the entire library, as the specificity factor (SF). As calculated, positions with the highest specificity will have the highest SF value. Primary anchor positions were then defined as those with an SF ≥2.4. This criterion identifies positions where the majority of residues are associated with significant decreases in binding capacity.

In selecting the specific peptide used as the basis for probing the binding specificity of each molecule in detail, we considered several different criteria before selecting one specific candidate. These criteria included, to afford the greatest sensitivity, the capacity of the wild-type peptide to bind with high affinity. We also privileged in our selection, as much as possible, peptides that had been previously reported as recognized by T cell responses and, secondarily, those reported as endogenously bound ligands, rather than those only described as “binders.” Finally, we also balanced the need to select peptides that would, on paper, be less problematic from a synthesis standpoint; thus, peptides with M or C residues, for example, were typically passed over as candidates in favor of another peptide with similar affinity for the respective HLA molecule.

Results

Selection of a representative panel of the DQ molecules most commonly encountered worldwide

Because of their extensive polymorphism, different HLA class II types are expressed at different frequencies in different ethnicities. Both DQα (DQA) and DQα (DQB) chains are polymorphic. On the basis of HLA crystal structures and sequence analyses, it is hypothesized that variation in both the DQA and DQB chains appear in regions likely to affect binding specificity, unlike the cases of DR and DP (37, 47, 52, 61–66). The frequency of specific DQ molecules resulting from expression of DQA and DQB chain allelic variants in various ethnicities, as reported at DbMHC [National Center for Biotechnology Information (58)], were compiled, with the goal of selecting a panel of DQ heterodimers representing the most common molecules overall encountered in major populations worldwide and thereby affording coverage of the majority of the human population, irrespective of ethnicity (Table I).

Table I.

Phenotypic frequencies of HLA-DQ molecules

| Molecule (DQA1*/DQB1*) |

Europe | North Africa |

North America |

Other | South America |

Southwest Asia |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0501/0301 | 29.5 | 24.0 | 50.3 | 40.4 | 76.2 | 38.9 | 26.2 | 40.8 |

| 0301/0302 | 12.7 | 10.2 | 67.6 | 44.8 | 24.0 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 23.4 |

| 0102/0602 | 16.3 | 15.0 | 1.5 | 9.6 | 0.0 | 11.9 | 34.0 | 12.6 |

| 0401/0402 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 20.7 | 26.4 | 29.5 | 3.2 | 21.9 | 16.0 |

| 0101/0501 | 16.8 | 18.9 | 1.5 | 15.1 | 0.0 | 15.7 | 25.9 | 13.4 |

| 0501/0201 | 19.1 | 17.0 | 2.7 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 17.2 | 12.6 | 10.9 |

| 0201/0201 | 16.7 | 20.3 | 1.9 | 10.5 | 2.0 | 14.2 | 9.7 | 10.8 |

| 0101/0503 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| 0102/0502 | 13.6 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.5 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| 0103/0601 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 |

| 03**/0302 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 6.5 |

| 0102/0601 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0103/0603 | 13.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 4.5 |

| 0301/0402 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 0102/0604 | 3.9 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 4.0 |

| Study panel | 77.4 | 72.5 | 98.2 | 95.8 | 96.0 | 71.6 | 89.3 | 85.8 |

Phenotypic frequencies derived from data available at DbMHC (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Accordingly, we selected a panel of six different HLA-DQ molecules (DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301,DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302,DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, DQA1*0101/DQB1* 0501, and DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201). This panel encompasses all DQ molecules with a frequency of >15% in at least three major populations for which frequency data are currently available, including Europe, North America, South America, Southeast Asia, Southwest Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, each molecule is found with an average phenotypic frequency across these populations of ≥10%. In aggregate, the panel covers ~85% of the average population, with equally high and balanced population coverage, ranging from 72 to 98%, for the populations listed on Table I.

Establishment of high-throughput HLA-DQ–binding assays

Previous studies have described the development of quantitative peptide-binding assays based on the use of purified MHC for each of the targeted specificities, specifically DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 (26, 30–34), DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301 (43), DQA1*0301/DQB1* 0302 (26, 30,35, 36), DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402 (44), DQA1*0101/ DQB1*0501 (45), and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 (46). However, the specific assays used different methodologies, including gel filtration, MHC capture and cell-bound MHCs, and also different readouts, such as biotinylation, fluorescence, and radioactivity. Because the sensitivity of these different assay systems ranged over several orders of magnitude, we sought to establish assays based on a single high-sensitivity platform.

Binding assays based on the inhibition of binding of a radiolabeled high-affinity ligand affords high-throughput capacity and high sensitivity, often in the 25 nM range for class II. To establish assays for the six molecules selected, we assembled a panel of known DQ epitopes, endogenous ligands, or ligands known to bind specific DQ molecules with high affinity. These peptides were radiolabeled and tested in direct binding assays for their capacity to bind purified DQ molecules, as described in Materials and Methods. For each DQ molecule, a ligand providing a strong and specific signal was identified (Table II). Ligand specificity was further verified by assessing capture with HLA class II locus-specific Abs (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Table II.

Optimized conditions for HLA-DQ binding assays

| Specificity |

Conditions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule (DQA1*/DQB1*) |

Serological Ag |

Preferred Cell Line(s)a |

Sequence | Sourceb | pH | Assay (h) | Sensitivity (IC50 nM) |

| 0501/0201 | DQ2.3 | VAVY | KPLLIIAEDVEGEY | E | 5.5 | 72 | 21 |

| 0501/0301 | DQ3.1 (7) | Herluf | YAHAAHAAHAAHAAHAA | A | 7 | 72 | 18 |

| 0301/0302 | DQ3.2 (8) | Preiss | EEDIEIIPIQEEEY | B | 5 | 48 | 26 |

| 0401/0402 | DQ4 | OLL | EEDIEIIPIQEEEY | B | 5 | 72 | 33 |

| 0101/0501 | DQ5(1) | LG2 | AAHSAAFEDLRVSSY | D | 7 | 72 | 12 |

| 0102/0602 | DQ6(1) | MGAR | AAATAGTTVYGAFAA | C | 7 | 72 | 13 |

MHC purification and capture assays for all alleles were performed as described in Materials and Methods using the SPVL3 mAb. All assays are performed at 37°C in a final Nonidet P-40 concentration of 0.15%, and with enough labeled peptide (0.1–1 nM) to provide 15,000 cpm radioactivity. Binding of the radiolabeled ligand is determined follow a 24-h capture of MHC molecules on Ab-coated plates.

The cell line used for the majority of experiments is shown. Alternative lines include Sweig (0501/0301), Yar and 145b (0301/0302), AMAI (0102/0602), RSH (0401/0402), and MAT, Cox, Steinlin, and QBL (0501/0201).

A, ROIV reiterative nonnatural ligand; B, Homo sapiens CD20 249; C, nonnatural analog of H. sapiens GAD65 334; D, influenza nucleoprotein 335; and E, Mycobacterium tuberculosis 65 kDa hsp 32.

To optimize the assays, the effects of pH, temperature, and duration of incubation and MHC capture times were investigated. A representative analysis is shown in Supplemental Fig. 2. In general, optimal assay conditions were different from those used for HLADR but similar to those for HLA-DP assays (Table II) (15, 29,53, 54). Specifically, DQ assays required, in most cases, incubation for 72 h at 37°C and an extended Ab capture step of up to 24 h. As with DR and DP, optimal pHs were in the 5–7 range, depending on the specific molecule. These optimal conditions were used in all subsequent competitive inhibition of binding assays. Assay sensitivities (IC50 of the unlabeled ligand) were in the 12–33 nM range.

Following the biochemical validation of the assays described above, we next sought to examine the correlation between assay specificity and the binding capacity of known HLA-restricted epitopes. For this purpose, we queried the Immune Epitope Database (http://www.iedb.org [67]) and selected a panel of 25 different epitopes and endogenous ligands (representing 27 different restriction events) presented by one or more of the six common DQ specificities selected in the current study (Table III). As shown, and similar to the case for HLA-DR and -DP (15, 29), in 81% (22 of 27) of the cases a DQ-restricted epitope or endogenous ligand bound its corresponding restricting molecule with a binding affinity of 1000 nM or better; ~50%of the cases were associated with affinities of 50 nM or better.

Table III.

HLA-DQ ligands and epitopes bind their restricting molecule with high affinity

| Binding Assay | Peptide | Source | Reported Restriction | Binding (IC50 nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 | AFILDGDNLFPKV | Betula pendula Bet v 1-A | DQB1*0201 | 7.5 |

| KPVSKMRMATPLLMQALP | Homo sapiens Ii chain | DQB1*0201 | 30 | |

| EEVDMTPADALDDFD | Herpesvirus UL48 | DQB1*0201 | 38 | |

| YQSYGPSGQYTHEFD | H. sapiens DQA | DQB1*0201 | 270 | |

| TEDQAMEDIKQMEAESIS | Bos taurus a-S1 casein | DQB1*0201 | 439 | |

| DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301 | DVKFPGGGQIVGGVYLLPRR | Hepatitis C polyprotein | DQB1*0301 | 4.8 |

| MGDDGVLACAIATHAKIRD | Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus Der p 2 | DQB1*0301 | 14 | |

| HGSEPCIIHRGKPFQLEAV | D. pteronyssinus Der p 2 | DQB1*0301 | 16 | |

| EYLNKIQNSLSTEWSPCSVT | Plasmodium falciparum CS | DQB1*0301 | 48 | |

| VLVPGCHGSEPCIIHR | D. pteronyssinus Der p 2 | DQB1*0301 | 3,898 | |

| DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302 | KDILEDERAAVDTYC | H. sapiens DRB1*0402 | DQB1*0302 | 77 |

| CDGERPTLAFLQDVM | H. sapiens GAD65 | DQB1*0302 | 94 | |

| DSNIMNSINNVMDEIDFFEK | P. falciparum 101 kDa | DQB1*0302 | 108 | |

| EEVDMTPADALDDFD | Herpesvirus UL48 | DQB1*0302 | 109 | |

| DCLLCAYSIEFGTNISKEHD | Gallus gallus ovomucoid | DQB1*0302 | 146 | |

| RMMEYGTTMVSYQPL | H. sapiens GAD65 | DQB1*0302 | 185 | |

| FDRSTKVIDFHYPNE | H. sapiens GAD65 | DQB1*0302 | 3,957 | |

| TPTEKDEYCARVNH | H. sapiens B2-m | DQB1*0302 | 29,516 | |

| DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402 | KDILEDERAAVDTYC | H sapiens DRB1*0402 | DQB1*0401 | 45 |

| DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501 | SDDELPYIDPNMEPV | Herpesvirus nuc | DQ5 | 41 |

| PLYRYLGGSFSHVL | C. trachomatis enolase | DQB1*0501 | 2,455 | |

| EELKSLNSVQAQYA | C. trachomatis CT579 | DQB1*0501 | 3,531 | |

| DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 | INEPTAAAIAYGLDR | H. sapiens HSP70 | DQB1*0602 | 6.3 |

| PPLYATGRLSQAQLMPSPPM | H. sapiens HSP70 | DQB1*0602 | 10 | |

| NNYGSTIEGLLD | Herpesvirus VP16 | DQB1*0602 | 118 | |

| RGYFKMRTGKSSIMRS | Influenza A hemagglutinin | DQB1*0602 | 369 | |

| NPRDAKACVVHGSDLK | H. sapiens ATPase | DQB1*0602 | 379 |

IC50 < 1000 nM are in bold.

Definition of peptide-binding motifs for HLA DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201, DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 molecules

Next, we used sets of single amino acid substitution (SAAS) analogs of prototype ligands to define specific binding motifs. ARB matrices were compiled on the basis of measured binding affinities, as described in Materials and Methods. As in previous studies (29, 59, 60), for each position an SF was calculated, and primary anchor positions were defined as those with an SF ≥ 2.4. At each main anchor, preferred residues were defined as those with ARB values within 5-fold of the optimal residue. In a first set of experiments, we analyzed DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201, DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, molecules for which putative motifs were previously defined using heterogeneous methodologies.

In the case of DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 (Supplemental Table I), our analysis identified F2 and D7 of the Bet v 1-A 21–35 peptide (sequence AFILDGDNLFPKV) as most crucial for binding, followed by F10 and P11. These positions correspond to a canonical HLA class II P1-P6-P9/10 anchor spacing (Table IV). Accordingly, the preferred residues at P1 were aromatic (F and W) or small hydrophobic (V), whereas at P6, the acidic residues E and D were preferred. At P9 the aromatic and hydrophobic residues W, M, I, and F were preferred. Interestingly, at P10 residues preferred represented a diverse set of chemical specificities, including small (P, A, and C), aromatic (W), polar (Q), basic (R), and acidic (E and D) residues. Taken together, this motif was in reasonable agreement with a consensus of previously published motifs for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 (26, 30–32, 34).

Table IV.

Summary HLA DQ motifs

| Position |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DQ Molecule | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P6 | P9 | P10 |

| DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 | FWV | ED | WMIF | PWQRACED | |||

| DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301 | YWGAFRCSQH | GPACS | APIVRLT | ||||

| DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302 | EQ | ||||||

| DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402 | VYATSCMWLGF | EDQF | |||||

| DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501 | YVEQR | WF | VLIM | ||||

| DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 | TASNMVLI | ILMV | ASG | ||||

In the case of DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, only position E11 of the human aminopeptidase 285–299 peptide (sequence EKKYFAATQFEPLAA, affinity 306 nM) was associated with an SF > 2.4. In this position the acidic residue E was by far the most preferred. The polar residue Q was also preferred, although with an ARB ~5-fold less than E (Table IV, Supplemental Table II). This preference for an acidic residue is in agreement with previously published motifs for DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302 (26, 30,35, 36), as well as a crystal structure (37), which place this specificity at P9 of the binding core. Unlike previous studies, however, we did not identify significant influences at other positions.

Finally, in the case of DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, positions T7, V9, and A12 of an analog of the GAD65 334–344 peptide were identified as main anchor positions (Table IV, Supplemental Table III). On the basis of a previously published DQB1*0602 crystal structure (47), as well as a previously published motif (46), we aligned these positions to correspond to a P4, P6, and P9 main anchor spacing. Position 4 was found to be associated with a preference for the small residues T, A, and S but also the small polar residue N and the hydrophobic/aliphatic residues M, V, L, and I. Position 6 was associated with a preference for the hydrophobic/aliphatic residues I, L, M, and V. As with position 4, position 9 has a preference for small residues, where A, S, and G were found to be associated with the highest binding. This motif is largely in agreement with previous reports (46, 47) of DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 binding specificity.

Taken together, the data in the present section have provided detailed motifs for three common HLA-DQ molecules. These motifs are largely compatible with previous reports, thereby validating the relevance of our approach.

Definition of peptide-binding motifs for HLA DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, and DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501 molecules

Next, we defined the peptide-binding specificity of the remaining DQ molecules, for each of which no detailed motif has been reported to date. Panels of SAAS of prototype molecule-specific binders were tested, and the data were analyzed as described above.

In the case of DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, positions G7, G8, and I10 of the hepatitis C virus polyprotein 21–35 peptide (sequence DVKFPGGGQIVGGVY) were identified as main anchors, with SF of 2.6, 4.2, and 2.8, respectively (Table IV, Supplemental Table IV). To comport with the spacing of the majority of class II motifs, we aligned these as the P3, P4, and P6 positions of the canonical class II core-binding region. Thus, in this case, no position corresponding to the prototypic aromatic/aliphatic P1 anchor, characteristic of nearly all class II MHC molecules, could be identified. This is similar to what was described above for DQB1*0602, associated with main anchors at P4, P6, and P9, and also reminiscent of the case of H-2 IAd molecules (IA is the murine locus corresponding to the human DQ locus), which is associated with P4 and P6 main anchors. In position 3, residues representing a broad chemical specificity were preferred and included aromatic (Y,W, and F), small (G, A, C, and S), basic (R and H), and polar (Q) residues. At position 4, the small residues A, G, and P, as well as the small acidic residues C and S, were preferred. Finally, the preference in position 6 was for the small residues P, A, and T, but also the hydrophobic/aliphatic residues V, I, and L, and the basic residue R. Interestingly, this motif is not dissimilar from that described previously for DQA1*0301/DQB1*0301, where main anchors spaced two positions apart were identified, with each having a preference for small residues (68).

What we believe is a unique anchor spacing was identified in the case of DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, where A7 and D14 of human HSP70 173–187 (sequence INEPTAAAIAYGLDR) were identified as main anchors, with SF of 3.0 and 2.9, respectively (Table IV, Supplemental Table V). If A7 is taken to be a P1 anchor, the resulting anchor pattern would correspond to a P1–P8 spacing. Alternatively, aligning D14 with P9, to correspond to the pattern observed for DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, would place A7 as a P2 anchor, delineating a P2–P9 spacing. Neither of these alignments has, to the best of our knowledge, been described for HLA class II. In Table IV, we have chosen the latter, P2–P9, alignment to reflect similarities in the binding repertoires of DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402 and DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302 (see below). In position 2, preferred residues were small (V, A, C, G, S, and T), aromatic (Y, W, and F), or aliphatic/hydrophobic (M and L). In this respect, the specificity at P2 may be more precisely described as the avoidance of acidic (D and E) and basic (H and K) residues. Position 9 is characterized by a preference for acidic residues (E and D), although the large polar residue Q and the aromatic residue F, were also allowed.

Finally, SAAS of FcεR 104–119 (sequence SQDLELSWNLNGLQAY) identified positions E5, W8, and L10 as the main anchor contacts for DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501, with SF of 5.6, 53, and 4.8, respectively (Table IV, Supplemental Table VI). These residues correspond to a P1-P4-P6 main anchor spacing pattern. At P1 the most preferred residues were Y, V, E, Q, and R, representing a somewhat diverse chemical specificity. At P4, which based on SF would appear to be the dominant anchor position, the aromatic residues W and F were preferred. Finally, the aliphatic/hydrophobic residues V, L, I, and M were preferred in position 6.

Summary of motifs associated with DQ peptide-binding specificity

Taken together, the data in the previous sections defined comprehensive quantitative binding motifs for each of the six most common HLA DQ specificities in the general population. A summary of the motif associated with each of the six different common DQ molecules, as defined above, is presented in Table IV.

On average, ~2.3 anchor positions were defined for each DQ molecule, similar to the cases of DR and DP. This anchor rate perhaps reflects the general structural similarities of these molecules and that they share a similar number of peptide-binding pockets (37, 47, 51, 52, 62, 63, 69). However, it is also apparent that, in general, motifs for DQ molecules are less sharply defined than for DR and DP molecules, consistent with the hypothesis that peptide anchor–MHC pocket interactions are less crucial for DQ binding. For example, in a recent report defining the motifs for five common DP molecules using the same methodology, DP anchor positions were associated with higher SF values (average, 8.95; median, 9.0) than DQ (average, 4.7; median, 4.8; excluding the unusually selective P4 anchor of DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501). Similarly, DP anchor preferences could typically be defined by a consistent chemical specificity, usually reflecting a requirement for aromatic and/or hydrophobic residues. For some DQ anchors, in contrast, preferences represented a wide, and sometimes even antithetical, range of chemical specificities, perhaps more reflective of the fact the overriding determinant is that certain residues are forbidden, rather than a direct preference.

When the motifs defined for the various DQ molecules are compared, each molecule is associated with what we believe is a unique spacing of main anchor residues, and differing specificity for the various positions is generally noted. These results, indicating significant divergence in the mode and specificity of binding, are very much in contrast to what has been shown for the most common HLA-DR (15) and -DP (29) molecules, where molecules of each loci could be aligned with a nearly identical main anchor pattern and specificity. In fact, it is difficult to identify even pairs of DQ molecules with similar motifs. For example, although DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 and DQA*0101/DQB1*0501 have a preference for aromatic residues at position 1, their specificities at position 6, where DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 prefers acidic residues and DQA*0101/DQB1*0501 prefers aliphatic/hydrophobic residues, are highly divergent. Perhaps the closest pairings involve DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301 and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, which share some overlap in their preferences for small or hydrophobic residues in positions 4 and 6, or DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302 and DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, which share preferences for acidic residues in position 9. However, even in these cases, any overlap in specificity is not readily apparent.

Taken together, the present data indicate that, unlike previous observations in the context of HLA-DR and -DP, a common DQ-supertypic specificity is not readily apparent.

Unexpected DQ cross-reactivity revealed by testing overlapping peptide and DQ epitope sets for binding to the various DQ allelic molecules

The data presented above demonstrated that the various DQ molecules considered have rather loose peptide-binding motifs, and the defined motifs differ significantly from each other. This would seem to imply that these differences would also translate into largely divergent peptide-binding repertoires. Thus, we next asked whether significant cross-reactivity would be observed with a large panel of random peptides. To address this point, we tested a panel of 425 nonredundant peptides for its capacity to bind each DQ molecule. The set of peptides consisted of 15-mer, overlapping by 10 residues, spanning the entire sequences of the P. pratense 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11, 12, and 13 pollen Ags, which are implicated in allergic reaction to timothy grass.

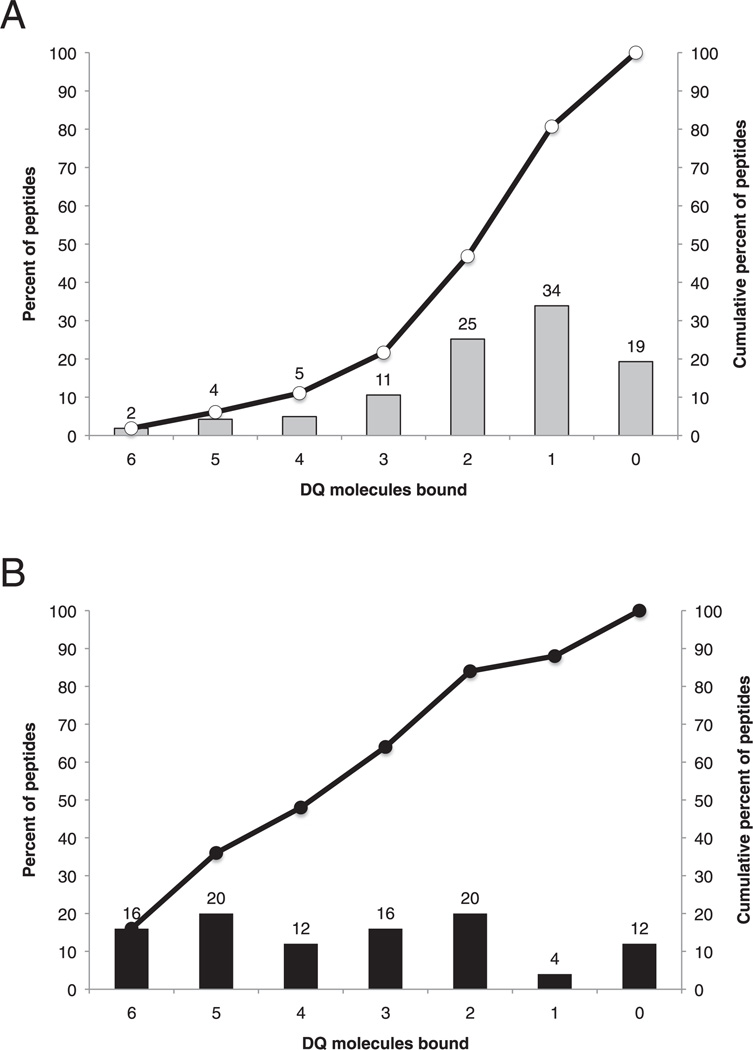

Approximately 28% of all possible DQ-binding events were associated with an affinity of 1000 nM or better (range, 15–64%), an overall rate not dissimilar to what has been previously observed with the same set of peptides for HLA-DP and -DR molecules [Sidney et al. (29) and J. Sidney and A. Sette, unpublished observations]. But somewhat surprisingly, given the differences in motifs, almost half of the peptides bound multiple DQ molecules, indicating that there is more overlap in the repertoires than random association. Altogether, 107 (25%) of the peptides bound two of the different DQ molecules tested and 45 (11%) bound three DQ molecules. Forty-seven (11%) peptides were very promiscuous DQ binders, binding more than half of the DQ molecules tested with an affinity of 1000 nM or better. This included 39 (9%) that bound four or five and eight (2%) that bound all six DQ molecules tested. By comparison, on the basis of the rates of binding to each individual molecule in our panel, it would have been expected that 17 peptides binding four or more molecules would have been identified. The high rate of cross-reactivity was found to be statistically significant (χ2; p < 0.00001).

Considering these observations, we examined the panel of HLA-DQ–restricted epitopes and endogenous ligands described above in Table III for their capacity to cross-react among different DQ molecules. Interestingly, an even higher level of cross-reactivity was found than with the panel of P. pratense overlapping peptides as 48% (n = 12) of known epitopes and ligands bound four or more of the six DQ molecules with an affinity of 1000 nM or better (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Rates of HLA-DQ promiscuous binding are higher than expected. A, A total of 425 nonredundant peptides were tested for their capacity to bind each of six common HLA-DQ molecules, as described in the text. The percent of peptides binding the indicated number of DQ molecules is shown in the bar chart. The cumulative total fraction of peptides binding at least the number of DQ molecules indicated is shown in the line plot. B, A set of HLA-DQ–restricted epitopes and endogenous ligands were tested for DQ-binding capacity. The fraction binding the indicated number of molecules is indicated as in A.

Taken together, these data reveal that despite apparently largely unrelated peptide-binding motifs, a surprising degree of cross-reactivity exists among DQ specificities. This is especially apparent when known DQ-restricted epitopes are considered. However, the patterns of overlap do not suggest that cross-reactive DQ binding is, in general, a function of a common, supertypic mode of binding.

Discussion

We have studied the peptide-binding specificity of the six most common HLA-DQ α/β heterodimers present in the worldwide population, namely DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501, and DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201. These molecules were found to be associated with rather divergent peptide-binding motifs, as defined using a uniform MHC-binding assay platform. Surprisingly, despite these differences in motifs, significant levels of repertoire overlaps were observed, especially when DQ-restricted epitopes are considered.

The molecules analyzed were selected on the basis of their frequent expression in the general population as a means to allow significant coverage of the worldwide population, including Europe, North America, South America, Southeast Asia, Southwest Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed the panel of molecules selected affords coverage of ~85% of the general population, with coverage exceeding 95% in several major population groups. A caveat in this respect is that the frequency of these molecules in Oceania and Australia is significantly lower. Future analyses of the motifs associated with additional DQ molecules prevalent in these populations (although much less so in the general population), such as DQA1* 0101/DQB1*0503, DQA1*0102/DQB1*0502, DQA1*0102/DQB1* 0601, DQA1*0103/DQB1*0601, and DQA1*0301/DQB1*0402, will be required to achieve comparable levels of coverage.

In our hands, DQ-binding assays have been more cumbersome from the technical point of view than DR and DP assays. These difficulties might be explained at least in part by the previously unappreciated, at least by us, requirement of DQ molecules for longer times of incubation (2–3 d as opposed to 24 h) and higher temperature (37°C as opposed to room temperature) to yield optimal signals. It may be hypothesized that the longer incubation time at higher temperature, compared with the conditions used for HLA-DR assays, reflects the presence of E in position 33 of most DQA chains, as opposed to H, whose pH sensitivity has been shown in an elegant study by Strominger’s group (70) to affect the half-life of DR–peptide complexes. We anticipate that the high-throughput assays optimized in this study will facilitate epitope identification studies, as well as the development of bioinformatic tools for the prediction of peptide binding for these common DQ molecules (67, 71). In the current study, these assays provided a uniform platform to define peptide motifs associated with DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, DQA1*0301/DQB1*03 02, DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, DQA1* 0101/DQB1*0501, and DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201 and allowed a direct comparison of overlaps in specificities and repertoires.

In the current study, we have used single amino acid substitution analogs of high-affinity binding peptides to probe binding specificity. The specific peptides used were 15 and 16 residues in length. Although this length in some cases may afford multiple possible binding frames, this selection was based on several important criteria. First, to afford the greatest sensitivity, we sought to select parent peptides binding the respective DQ molecule with high affinity. To maximize biological relevance, we also privileged peptides previously reported as recognized by T cell responses or being endogenously bound ligands. Finally, we also selected peptides least problematic from a synthesis standpoint. The use of 12- or 13-mer peptides previously characterized in structural studies would have represented an alternative strategy. Besides inherently having fewer possible binding frames/cores, these peptides would also allow direct comparison with crystallography data.

The corresponding motifs were found to be compatible with previous reports that analyzed some of these molecules using less homogenous assay and testing strategies (26, 30–36, 43–46). In general, the motifs associated with the various DQ molecules were rather divergent from each other. These observations are in contrast with previous observations that indicated that most HLA-DRB1 allelic variants have similar supertype specificity (see, for example, Ref. 15). Similarly, the existence of a DP supertype encompassing at least six of the most common DP molecules has been reported (27–29). In both cases, clear similarities in the peptide-binding motifs associated with the various molecules encoded by the DR and DP loci were readily apparent.

Although in general terms our results are in good agreement with most of the results described in the literature, there are some discrepancies or interesting differences. For example, in the context of P1 of DQ2, we have found that Asp and Glu are accommodated barely better than Arg and Lys, whereas based on published structures, it could be inferred that acidic residues would be accommodated far better than basic ones. It is also possible that proline at P1 might have had a better ARB had the peptide been extended by one residue on its N terminus to engage all possible hydrogen bonds. Also, still in the case of DQ2, the CLIP used and shown in this paper to bind with an affinity of 30 nM was previously reported to bind with ~ 1000-fold less affinity. This latter discrepant result can perhaps be explained by the optimized binding assay conditions that have been used in this report, which may allow to more readily detect high-affinity binding. Finally, in the case of DQ8, at p9 it was noted that R is associated with equal anchor potency as D, whereas previous binding experiments from other laboratories (26, 30, 35, 36), as well as a crystal structure (37), have shown that D/E have equal potency at this pocket and R/K/H are excluded. Also, at p4 our results show Y to be slightly better or worse accommodated as E, D, Q, and N when crystallography and previous binding experiments have shown decent accommodation for F/Y and poor for D/E and Q/N. These apparent discrepancies might reflect differences in methodology and/or effects associated with the specific ligands used in the experiments. It is also possible that some of the paradoxical or divergent preference patterns observed are the result of the use of longer peptides, which may use alternative binding frames.

Comparatively, the motifs we have described for HLA-DQ were surprisingly “loose,” with few main anchor positions associated with dominant effects on binding. Similarly, in several cases, the range of residues preferred at specific anchor positions represented a relatively diverse set of chemical specificities. These observations suggest that perhaps DQ binding is less contingent upon strong peptide–MHC pocket interactions but instead is more dependent upon backbone interactions. These observations are consistent with previous studies analyzing the structure of DQ molecules and IA molecules (the murine ortholog of DQ) (37, 47–52). Those studies pointed out that in several instances the peptide-binding pockets of the MHC were either not engaged by the amino acid side chains of the peptide ligands, or when engaged, the interaction appeared to contribute relatively little to the overall binding energy. Conversely, much of the binding energy appeared to take place with lateral interaction between the peptide and the α helices demarcating the peptide-binding groove. This is in contrast with most common DR and DP molecules, where anchor residues engaging the main MHC peptide-binding pockets contribute much of the binding affinity, and clear anchors and allele-specific binding motifs can be more easily discerned.

Several publications from Stern’s group (72–75) using DR1 and the HA306–318 peptide showed that the exquisite fitting of an aromatic residue at p1 determines peptide affinity for a DR-b86G+ allele. By contrast, in DQ alleles, two or more different pockets can be of importance by being selective, whereas other pockets may be less restrictive. Indeed, the lateral interactions are important, and the strict conservation of the MHC class II residues interacting with the peptide backbone testifies to their importance. In this paper, the experiments suggested the presence of the p10 shelf for DQ2, also shown by the Stern group (76) for DR1, and by crystallography for DQ2 (64) with p9 being unoccupied.

Despite some differences, the peptide-binding mode of DQ molecules shares fundamental characteristics with DR and DQ molecules. Overall, each of the DQ molecules tested bound between 14 and 63% of the peptides tested at the 1000 nM level. These levels of binding are consistent, both in terms of frequency and affinity, with what we have observed with other HLA class II molecules encoded in the DR and DP loci (13, 15, 29, 77, 78). Furthermore, >80% of known DQ-restricted epitopes bound their respective restricting MHC molecule with an affinity of 1000 nM or better. The binding rates and affinities detected are similar to what was previously described for HLA-DR and -DP epitopes (15, 29) and suggest that 1000 nM is a generally applicable threshold for biologically relevant binding in the context of HLA class II.

When the overlap in peptide-binding repertoire between different DQ molecules was examined by testing a panel of peptides spanning a set of P. pratense Ags and panels of known DQ epitopes, a significant and substantial overlap was revealed. In fact, several peptides were identified that have the capacity to bind all six of the DQ molecules tested with affinities of 100 nM or better (see, for example, Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. 1E, 1H, 1I). As noted above, a relatively minor role of peptide-binding pockets and a more prominent role of lateral interactions provide the most likely explanation for this otherwise apparent paradox. On average, ~25% of the repertoires of any pair of the DQ molecules studied overlap, which significantly exceeds what would be expected at random. The biological relevance of the binding overlap is emphasized by the fact that ~48% of the known DQ epitopes were found to be promiscuous DQ binders, having the capacity to bind four or more of the six DQ molecules tested.

It is also possible that cross-reactivity between different molecules is due to the ability of peptides to use different frames, depending on the specific molecule. That this is possible in the case of DQ has been shown previously (26) and suggested in modeling studies (66). Furthermore, this type of cross-reactivity is perhaps related to the previously reported phenomenon of epitope/motif clustering, or “hot spots” (79–85). It has been reported that certain protein regions are targets of T cells restricted by multiple HLA specificities that recognize overlapping, yet distinct, peptides. It has been hypothesized that this clustering occurs significantly more frequently than would be expected by random chance. The available data suggest that it may be possible to identify highly promiscuous helper T cell epitopes capable of mediating activation of T cells restricted by multiple HLA molecules either within a locus (DR, DQ, or DP) or even across multiple loci.

Previous studies in the DR system have shown that promiscuous binders can bind in similar registers and that indeed pan-DR–binding peptides can be engineered (86, 87). It is further possible that the same peptide can bind different HLA class II in different registers. In either case, such promiscuous binders, of obvious interest for vaccine applications, could be detected by either a “brute force” approach, namely scanning pathogenic or allergenic proteins and performing relevant binding experiments, and/or by using multiple allele specific bioinformatic predictions (71, 88, 89).

In conclusion, in the current study, we describe assays and peptide-binding motifs for the most common DQ molecules. These motifs are in general agreement with those described previously for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0201, DQA1*0301/DQB1*0302, and DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 (26, 30–32, 34–36, 46) but also represent more detailed quantification of the specificity of these alleles. Motifs for DQA1*0501/DQB1*0301, DQA1*0401/DQB1*0402, and DQA1*0101/DQB1*0501 are novel, to the best of our knowledge, at least in terms of the level of their detail. Our experiments reveal discordant motifs but an unexpected high degree of overlap between the peptide-binding repertoires of these molecules. We anticipate that the data presented in this paper will facilitate molecular studies identifying and investigating in more detail the specificity of DQ-restricted epitopes, which despite their contribution to HLA class II responses and potentially crucial roles in association with several autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus (38–42), have thus far received much less attention than their DR-restricted counterparts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carla Oseroff and Howard Grey for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Contracts HHSN266200400006C, HHSN272200900044C, HHSN272200900042C, and HHSN272200700048C (all to A.S.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- ARB

average relative binding affinity

- DQA

DQ α

- DQB

DQ β

- SAAS

single amino acid substitution

- SF

specificity factor

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Doherty PC, Zinkernagel RM. A biological role for the major histocompatibility antigens. Lancet. 1975;1:1406–1409. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. H-2 compatability requirement for T-cell–mediated lysis of target cells infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: different cytotoxic T-cell specificities are associated with structures coded for in H-2K or H-2D. J. Exp. Med. 1975;141:1427–1436. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doherty PC, Zinkernagel RM. H-2 compatibility is required for T-cell–mediated lysis of target cells infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Exp. Med. 1975;141:502–507. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.2.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. The discovery of MHC restriction. Immunol. Today. 1997;18:14–17. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein J. Natural History of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes AL, Nei M. Maintenance of MHC polymorphism. Nature. 1992;355:402–403. doi: 10.1038/355402b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holdsworth R, Hurley CK, Marsh SG, Lau M, Noreen HJ, Kempenich JH, Setterholm M, Maiers M. The HLA dictionary 2008: a summary of HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1/3/4/5, and -DQB1 alleles and their association with serologically defined HLA-A, -B, -C, -DR, and -DQ antigens. Tissue Antigens. 2009;73:95–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson J, Waller MJ, Parham P, de Groot N, Bontrop R, Kennedy LJ, Stoehr P, Marsh SG. IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:311–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sette A, Sidney J. Nine major HLA class I supertypes account for the vast preponderance of HLA-A and -B polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s002510050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sette A, Sidney J. HLA supertypes and supermotifs: a functional perspective on HLA polymorphism. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:478–482. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sidney J, Peters B, Frahm N, Brander C, Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund O, Nielsen M, Kesmir C, Petersen AG, Lundegaard C, Worning P, Sylvester-Hvid C, Lamberth K, Røder G, Justesen S, et al. Definition of supertypes for HLA molecules using clustering of specificity matrices. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:797–810. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doolan DL, Southwood S, Chesnut R, Appella E, Gomez E, Richards A, Higashimoto YI, Maewal A, Sidney J, Gramzinski RA, et al. HLA-DR-promiscuous T cell epitopes from Plasmodium falciparum pre-erythrocytic-stage antigens restricted by multiple HLA class II alleles. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1123–1137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson CC, Palmer B, Southwood S, Sidney J, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, Chesnut R, Sette A, Livingston BD. Identification and antigenicity of broadly cross-reactive and conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1- derived helper T-lymphocyte epitopes. J. Virol. 2001;75:4195–4207. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4195-4207.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Southwood S, Sidney J, Kondo A, del Guercio MF, Appella E, Hoffman S, Kubo RT, Chesnut RW, Grey HM, Sette A. Several common HLA-DR types share largely overlapping peptide binding repertoires. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3363–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chelvanayagam G. A roadmap for HLA-DR peptide binding specificities. Hum. Immunol. 1997;58:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(97)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doytchinova IA, Flower DR. In silico identification of supertypes for class II MHCs. J. Immunol. 2005;174:7085–7095. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibert M, Balandraud N, Touinssi M, Mercier P, Roudier J, Reviron D. Functional categorization of HLA-DRB1 alleles in rheumatoid arthritis: the protective effect. Hum. Immunol. 2003;64:930–935. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibert M, Sanchez-Mazas A. Geographic patterns of functional categories of HLA-DRB1 alleles: a new approach to analyse associations between HLA-DRB1 and disease. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 2003;30:361–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2370.2003.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ou D, Mitchell LA, Décarie D, Tingle AJ, Nepom GT. Promiscuous T-cell recognition of a rubella capsid protein epitope restricted by DRB1*0403 and DRB1*0901 molecules sharing an HLA DR supertype. Hum. Immunol. 1998;59:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ou D, Mitchell LA, Tingle AJ. HLA-DR restrictive supertypes dominate promiscuous T cell recognition: association of multiple HLA-DR molecules with susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. J. Rheumatol. 1997;24:253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou D, Mitchell LA, Tingle AJ. A new categorization of HLA DR alleles on a functional basis. Hum. Immunol. 1998;59:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer J, Valsasnini P, Tolba K, Bolin D, Higelin J, Takacs B, Sinigaglia F. Promiscuous and allele-specific anchors in HLA-DR–binding peptides. Cell. 1993;74:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90306-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raddrizzani L, Sturniolo T, Guenot J, Bono E, Gallazzi F, Nagy ZA, Sinigaglia F, Hammer J. Different modes of peptide interaction enable HLA-DQ and HLA-DR molecules to bind diverse peptide repertoires. J. Immunol. 1997;159:703–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinigaglia F, Hammer J. Motifs and supermotifs for MHC class II binding peptides. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:449–451. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sidney J, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, Sette A. The HLA molecules DQA1*0501/B1*0201 and DQA1*0301/B1*0302 share an extensive overlap in peptide binding specificity. J. Immunol. 2002;169:5098–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen WM, Pouvelle-Moratille S, Wang XF, Farci S, Munier G, Charron D, Ménez A, Busson M, Maillére B. Scanning the HIV genome for CD4+ T cell epitopes restricted to HLA-DP4, the most prevalent HLA class II molecule. J. Immunol. 2006;176:5401–5408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castelli FA, Buhot C, Sanson A, Zarour H, Pouvelle-Moratille S, Nonn C, Gahery-Ségard H, Guillet JG, Ménez A, Georges B, Maillère B. HLA-DP4, the most frequent HLA II molecule, defines a new supertype of peptide-binding specificity. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6928–6934. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sidney J, Steen A, Moore C, Ngo S, Chung J, Peters B, Sette A. Five HLA-DP molecules frequently expressed in the worldwide human population share a common HLA supertypic binding specificity. J. Immunol. 2010;184:2492–2503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godkin AJ, Davenport MP, Willis A, Jewell DP, Hill AV. Use of complete eluted peptide sequence data from HLA-DR and -DQ molecules to predict T cell epitopes, and the influence of the nonbinding terminal regions of ligands in epitope selection. J. Immunol. 1998;161:850–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Wal Y, Kooy YM, Drijfhout JW, Amons R, Papadopoulos GK, Koning F. Unique peptide binding characteristics of the disease-associated DQ(α 1*0501, β 1*0201) vs the non–disease-associated DQ(α 1*0201, β 1*0202) molecule. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:484–492. doi: 10.1007/s002510050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vartdal F, Johansen BH, Friede T, Thorpe CJ, Stevanović S, Eriksen JE, Sletten K, Thorsby E, Rammensee HG, Sollid LM. The peptide binding motif of the disease associated HLA-DQ (α 1* 0501, β 1* 0201) molecule. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:2764–2772. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quarsten H, Paulsen G, Johansen BH, Thorpe CJ, Holm A, Buus S, Sollid LM. The P9 pocket of HLA-DQ2 (non-Aspb57) has no particular preference for negatively charged anchor residues found in other type 1 diabetes-predisposing non-Aspβ57 MHC class II molecules. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:1229–1236. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.8.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johansen BH, Gjertsen HA, Vartdal F, Buus S, Thorsby E, Lundin KE, Sollid LM. Binding of peptides from the N-terminal region of a-gliadin to the celiac disease-associated HLA-DQ2 molecule assessed in biochemical and T cell assays. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996;79:288–293. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwok WW, Domeier ML, Raymond FC, Byers P, Nepom GT. Allele-specific motifs characterize HLA-DQ interactions with a diabetes-associated peptide derived from glutamic acid decarboxylase. J. Immunol. 1996;156:2171–2177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straumfors A, Johansen BH, Vartdal F, Sollid LM, Thorsby E, Buus S. A peptide-binding assay for the disease-associated HLA-DQ8 molecule. Scand. J. Immunol. 1998;47:561–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee KH, Wucherpfennig KW, Wiley DC. Structure of a human insulin peptide-HLA-DQ8 complex and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:501–507. doi: 10.1038/88694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanjeevi CB. Genes influencing innate and acquired immunity in type 1 diabetes and latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1079:67–80. doi: 10.1196/annals.1375.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Megiorni F, Mora B, Bonamico M, Barbato M, Nenna R, Maiella G, Lulli P, Mazzilli MC. HLA-DQ and risk gradient for celiac disease. Hum. Immunol. 2009;70:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolters VM, Wijmenga C. Genetic background of celiac disease and its clinical implications. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008;103:190–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baschal EE, Eisenbarth GS. Extreme genetic risk for type 1A diabetes in the post-genome era. J. Autoimmun. 2008;31:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiao SW, Sollid LM, Blumberg RS. Antigen presentation in celiac disease. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009;21:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ihle J, Fleckenstein B, Terreaux C, Beck H, Albert ED, Dannecker GE. Differential peptide binding motif for three juvenile arthritis associated HLA-DQ molecules. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2003;21:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volz T, Schwarz G, Fleckenstein B, Schepp CP, Haug M, Roth J, Wiesmüller KH, Dannecker GE. Determination of the peptide binding motif and high-affinity ligands for HLA-DQ4 using synthetic peptide libraries. Hum. Immunol. 2004;65:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chicz RM, Lane WS, Robinson RA, Trucco M, Strominger JL, Gorga JC. Self-peptides bound to the type I diabetes associated class II MHC molecules HLA-DQ1 and HLA-DQ8. Int. Immunol. 1994;6:1639–1649. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.11.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ettinger RA, Kwok WW. A peptide binding motif for HLA-DQA1* 0102/DQB1*0602, the class II MHC molecule associated with dominant protection in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Immunol. 1998;160:2365–2373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siebold C, Hansen BE, Wyer JR, Harlos K, Esnouf RE, Svejgaard A, Bell JI, Strominger JL, Jones EY, Fugger L. Crystal structure of HLA-DQ0602 that protects against type 1 diabetes and confers strong susceptibility to narcolepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1999–2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308458100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Y, Rudensky AY, Corper AL, Teyton L, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of MHC class II I-Ab in complex with a human CLIP peptide: prediction of an I-Ab peptide-binding motif. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:1157–1174. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott CA, Peterson PA, Teyton L, Wilson IA. Crystal structures of two I-Ad-peptide complexes reveal that high affinity can be achieved without large anchor residues. Immunity. 1998;8:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80537-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fremont DH, Monnaie D, Nelson CA, Hendrickson WA, Unanue ER. Crystal structure of I-Ak in complex with a dominant epitope of lysozyme. Immunity. 1998;8:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ettinger RA, Liu AW, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. β 57-Asp plays an essential role in the unique SDS stability of HLA-DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 α β protein dimer, the class II MHC allele associated with protection from insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Immunol. 2000;165:3232–3238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moustakas AK, van de Wal Y, Routsias J, Kooy YM, van Veelen P, Drijfhout JW, Koning F, Papadopoulos GK. Structure of celiac disease-associated HLA-DQ8 and non-associated HLA-DQ9 alleles in complex with two disease-specific epitopes. Int. Immunol. 2000;12:1157–1166. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.8.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sidney J, Southwood S, Oseroff C, del Guercio MF, Sette A, Grey HM. Measurement of MHC/peptide interactions by gel filtration. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1803s31. Chapter 18: Unit 18.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaufmann DE, Bailey PM, Sidney J, Wagner B, Norris PJ, Johnston MN, Cosimi LA, Addo MM, Lichterfeld M, Altfeld M, et al. Comprehensive analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD4 responses reveals marked immunodominance of gag and nef and the presence of broadly recognized peptides. J. Virol. 2004;78:4463–4477. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4463-4477.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gulukota K, Sidney J, Sette A, DeLisi C. Two complementary methods for predicting peptides binding major histocompatibility complex molecules. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:1258–1267. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sidney J, Grey HM, Southwood S, Celis E, Wentworth PA, del Guercio MF, Kubo RT, Chesnut RW, Sette A. Definition of an HLA-A3–like supermotif demonstrates the overlapping peptide-binding repertoires of common HLA molecules. Hum. Immunol. 1996;45:79–93. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(95)00173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meyer D, Singe RM, Mack SJ, Lancaster A, Nelson MP, Erlich H, Fernandez-Vina M, Thomson G. Single locus polymorphism of classical HLA genes. In: Hansen J, editor. Immunobiology of the Human MHC: Proceedings of the 13th International Histocompatibility Workshop and Conference; Seattle: IHWG Press; 2007. pp. 653–704. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sidney J, Assarsson E, Moore C, Ngo S, Pinilla C, Sette A, Peters B. Quantitative peptide binding motifs for 19 human and mouse MHC class I molecules derived using positional scanning combinatorial peptide libraries. Immunome Res. 2008;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sidney J, Peters B, Moore C, Pencille TJ, Ngo S, Masterman KA, Asabe S, Pinilla C, Chisari FV, Sette A. Characterization of the peptide-binding specificity of the chimpanzee class I alleles A*0301 and A*0401 using a combinatorial peptide library. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:745–751. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghosh P, Amaya M, Mellins E, Wiley DC. The structure of an intermediate in class II MHC maturation: CLIP bound to HLA-DR3. Nature. 1995;378:457–462. doi: 10.1038/378457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stern LJ, Brown JH, Jardetzky TS, Gorga JC, Urban RG, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the human class II MHC protein HLA-DR1 complexed with an influenza virus peptide. Nature. 1994;368:215–221. doi: 10.1038/368215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madden DR. The three-dimensional structure of peptide-MHC complexes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1995;13:587–622. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim CY, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid LM. Structural basis for HLA-DQ2–mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4175–4179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ettinger RA, Papadopoulos GK, Moustakas AK, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. Allelic variation in key peptide-binding pockets discriminates between closely related diabetes-protective and diabetes-susceptible HLA-DQB1*06 alleles. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1988–1998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tong JC, Zhang GL, Tan TW, August JT, Brusic V, Ranganathan S. Prediction of HLA-DQ3.2b ligands: evidence of multiple registers in class II binding peptides. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1232–1238. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peters B, Sidney J, Bourne P, Bui HH, Buus S, Doh G, Fleri W, Kronenberg M, Kubo R, Lund O, et al. The immune epitope database and analysis resource: from vision to blueprint. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sidney J, Oseroff C, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, Krieger JI, Ishioka GY, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Sette A. Definition of a DQ3.1-specific binding motif. J. Immunol. 1994;152:4516–4525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McFarland BJ, Beeson C. Binding interactions between peptides and proteins of the class II major histocompatibility complex. Med. Res. Rev. 2002;22:168–203. doi: 10.1002/med.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rötzschke O, Lau JM, Hofstätter M, Falk K, Strominger JL. A pH-sensitive histidine residue as control element for ligand release from HLA-DR molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16946–16950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212643999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang P, Sidney J, Dow C, Mothé B, Sette A, Peters B. A systematic assessment of MHC class II peptide binding predictions and evaluation of a consensus approach. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murthy VL, Stern LJ. The class II MHC protein HLA-DR1 in complex with an endogenous peptide: implications for the structural basis of the specificity of peptide binding. Structure. 1997;5:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Natarajan SK, Stern LJ, Sadegh-Nasseri S. Sodium dodecyl sulfate stability of HLA-DR1 complexes correlates with burial of hydrophobic residues in pocket 1. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3463–3470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zarutskie JA, Sato AK, Rushe MM, Chan IC, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Stern LJ. A conformational change in the human major histocompatibility complex protein HLA-DR1 induced by peptide binding. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5878–5887. doi: 10.1021/bi983048m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sato AK, Zarutskie JA, Rushe MM, Lomakin A, Natarajan SK, Sadegh-Nasseri S, Benedek GB, Stern LJ. Determinants of the peptide-induced conformational change in the human class II major histocompatibility complex protein HLA-DR1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2165–2173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zavala-Ruiz Z, Strug I, Anderson MW, Gorski J, Stern LJ. A polymorphic pocket at the P10 position contributes to peptide binding specificity in class II MHC proteins. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1395–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sette A, Sidney J, Oseroff C, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, Arrhenius T, Powell MF, Colón SM, Gaeta FC, Grey HM. HLA DR4w4-binding motifs illustrate the biochemical basis of degeneracy and specificity in peptide-DR interactions. J. Immunol. 1993;151:3163–3170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sidney J, Oseroff C, Southwood S, Wall M, Ishioka G, Koning F, Sette A. DRB1*0301 molecules recognize a structural motif distinct from the one recognized by most DR β 1 alleles. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2634–2640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arentz-Hansen H, McAdam SN, Molberg O, Fleckenstein B, Lundin KE, Jørgensen TJ, Jung G, Roepstorff P, Sollid LM. Celiac lesion T cells recognize epitopes that cluster in regions of gliadins rich in proline residues. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:803–809. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Higgins JA, Thorpe CJ, Hayball JD, O’Hehir RE, Lamb JR. Overlapping T-cell epitopes in the group I allergen of Dermatophagoides species restricted by HLA-DP and HLA-DR class II molecules. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1994;93:891–899. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahlers JD, Pendleton CD, Dunlop N, Minassian A, Nara PL, Berzofsky JA. Construction of an HIV-1 peptide vaccine containing a multideterminant helper peptide linked to a V3 loop peptide 18 inducing strong neutralizing antibody responses in mice of multiple MHC haplotypes after two immunizations. J. Immunol. 1993;150:5647–5665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown SA, Lockey TD, Slaughter C, Slobod KS, Surman S, Zirkel A, Mishra A, Pagala VR, Coleclough C, Doherty PC, Hurwitz JL. T cell epitope “hotspots” on the HIV Type 1 gp120 envelope protein overlap with tryptic fragments displayed by mass spectrometry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2005;21:165–170. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gupta V, Tabiin TM, Sun K, Chandrasekaran A, Anwar A, Yang K, Chikhlikar P, Salmon J, Brusic V, Marques ET, et al. SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid immunodominant T-cell epitope cluster is common to both exogenous recombinant and endogenous DNA-encoded immunogens. Virology. 2006;347:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meinl E, Weber F, Drexler K, Morelle C, Ott M, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Goebels N, Ertl B, Jechart G, Giegerich G, et al. Myelin basic protein-specific T lymphocyte repertoire in multiple sclerosis: complexity of the response and dominance of nested epitopes due to recruitment of multiple T cell clones. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:2633–2643. doi: 10.1172/JCI116879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muller CP, Bünder R, Mayser H, Ammon S, Weinmann M, Brons NH, Schneider F, Jung G, Wiesmüller KH. Intramolecular immunodominance and intermolecular selection of H2d-restricted peptides define the same immunodominant region of the measles virus fusion protein. Mol. Immunol. 1995;32:37–47. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)00132-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O’Sullivan D, Arrhenius T, Sidney J, Del Guercio MF, Albertson M, Wall M, Oseroff C, Southwood S, Colón SM, Gaeta FC, et al. On the interaction of promiscuous antigenic peptides with different DR alleles: identification of common structural motifs. J. Immunol. 1991;147:2663–2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alexander J, Sidney J, Southwood S, Ruppert J, Oseroff C, Maewal A, Snoke K, Serra HM, Kubo RT, Sette A, et al. Development of high potency universal DR-restricted helper epitopes by modification of high affinity DR-blocking peptides. Immunity. 1994;1:751–761. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Blicher T, Peters B, Sette A, Justesen S, Buus S, Lund O. Quantitative predictions of peptide binding to any HLA-DR molecule of known sequence: NetMHCIIpan. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nielsen M, Lund O, Buus S, Lundegaard C. MHC Class II epitope predictive algorithms. Immunology. 2010;130:319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]