Abstract

Background:

Till today, there has been some hesitation to accept the role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in pelvic mass. We have tried to study the role of ultrasonography (USG) and computed tomography (CT) guided FNAC as diagnostic and supportive investigation for ovarian tumors.

Aim:

To evaluate the current status of image-directed percutaneous aspiration of ovarian neoplasm for the purpose of early detection of malignancy.

Materials and Methods:

Seventy-four fine needle aspirations of ovarian neoplasms were performed between January 2007 and December 2008 by transabdominal approach under USG and CT guidance and correlated with histopathological findings and tumor markers.

Results:

A total of 47 (63.5%) cases were assessed as malignant and 21 (28.3%) as benign and 6 (8.1%) as inconclusive. The neoplastic lesions were categorized as per World Health Organization (WHO) classification.

Conclusion:

With the availability of modern techniques, USG and CT guided FNAC can be an optimum modality for the diagnosis of primary and metastatic ovarian neoplasms and evaluation of recurrent malignant tumors, which has great impact on patient management consequently.

Keywords: Fine needle aspiration cytology, ovarian tumors, histopathology

Introduction

Cytology has been underutilized as a modality for the diagnosis of ovarian tumors. With the advent of accurate imaging techniques like ultrasonography (USG) and computed tomography (CT) scan in detecting the ovarian lesions and omental or peritoneal deposit, guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has assumed a definite role in diagnosis and management. There is clear association between the stages and prognosis of ovarian malignant tumors. Since two-thirds of epithelial ovarian cancer cases present at advanced stages and have a low 5-year survival rate, early evaluation of ovarian lesions is very important.[1,2] Those women diagnosed with disease confined to ovary often require less aggressive surgical intervention, may not require chemotherapy and have an overall 5-year survival rate of approximating 90%.[1]

The aims and objectives of the study were initial evaluation of ovarian masses before treatment. In solid ovarian masses, we attempted to define tumor type. In partly solid and partly cystic tumors, FNAC was done for early diagnosis of malignancy, and in cystic tumors, we tried to exclude malignancy.

Materials and Methods

A prospective study was conducted from January 2007 to December 2008. Seventy-four cases were evaluated by transabdominal percutaneous approach under USG and CT guidance as a part of the institutional protocol. Any pelvic mass, clinically or radiologically suspected as ovarian malignancy in the outpatient department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, was selected. FNAC was done in patients when imaging findings suggested non-functional complex ovarian cysts. Ovarian tumors that needed exclusion of borderline tumors or malignant tumors by the clinician and that were sent to the Department of Pathology for image-guided FNAC were also included in the study. Any patient with coagulopathy was excluded from this study.

Proper consent was taken for the procedure. The patient was prepared with antiseptic dressings. The mass was localized under the guidance of an expert radiologist by USG or CT. Aspiration was done from the appropriate site by commercially available 22-G, 88-mm long spinal needle attached to a 10-mL disposable syringe. With able guidance, we could visualize the structure of the lesion and reach precisely the desired site in any plane. But we faced difficulty in the presence of significant ascitis when the aspirate was not satisfactory in the face of advanced malignancy. Poor patient tolerance also caused difficulty in some cases. Specimens were immediately smeared on glass slides and air dried for Leishman-Giemsa stain. Wet fixed smears were stained by Papanicolaou stain. Records of clinical and radiological data as well as tumor markers like Cancer Antigen 125 (CA 125) and alpha fetoprotein (AFP), if available, were correlated. Ascitic fluid or pleural fluid cytology for detection of malignant cells was also done in appropriate cases. The results were compared with the histopathology reports accepted as the gold standard.

Results

The present study consisted of 74 cases. The age range varied from 2 to 65 years, mean age being 42 years. In the pediatric age group, we found primitive germ cell tumor and a case of non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving ovary. Clinically, most of the patients presented with abdominal swelling and pain. USG or CT revealed 21 solid tumors, 36 partly solid and partly cystic tumors and 17 cystic tumors. The distribution of malignant tumors including the germ cell tumors and benign tumors and comparison of cytological and histopathological diagnosis is presented in Table 1. Aspirates from serous cystadenomas were often hypocellular with occasional single epithelial cells or aggregates of uniform cuboidal cells. The mucinous cystadenomas showed a few isolated columnar cells or a few sheets of columnar mucin producing cells with abundant free mucin in the background. The granulosa cell tumor had cellular smear consisting of small neoplastic cells with scanty cytoplasm and nuclear grooves. Benign squamous epithelial cells, anucleate squames and keratin debris were present in aspirates of mature cystic teratomas. The aspirates from fibroma contained sparse cellular material with spindle cells.

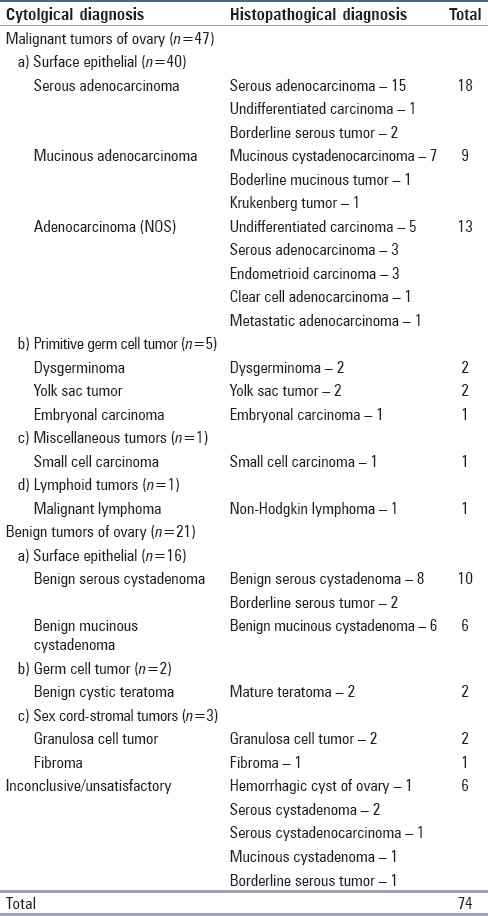

Table 1.

Histopathological correlation with our cytological diagnosis

The cells of serous adenocarcinoma occurred in papillary groups with hyperchromatic nuclei and irregular coarsely granular chromatin [Figure 1]. Mucinous adenocarcinoma revealed pleomorphic nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm of the cells with mucin in the background. The identification of metastatic tumors was extremely difficult in aspiration cytology unless relevant clinical history and investigation reports were supplied. No Brenner tumor was found in our cytology specimens but a case diagnosed as mucinous cystadenoma cytologically had in addition a component of Brenner tumor on histopathology. Most of the primitive germ cell tumors could be reliably diagnosed and subtyped on FNA. The component of a mixed germ cell tumor was missed in cytology. Needle aspiration of dysgerminoma yielded abundant neoplastic germ cells in dispersed fashion with highly fragile cytoplasm, large nuclei and prominent single or multiple nucleoli. Small mature lymphocytes, a component of the lesion, were also present in the background [Figure 2]. The aspirates of yolk sac tumor were fairly cellular with papillary clusters representing Schiller-Duval bodies, cytoplasmic vacuolations were prominent in the cells and periodic acid schiff (PAS) positive intra-and extracellular hyaline globules were seen [Figure 3]. Cell-rich smears were obtained in embryonal carcinoma with cell aggregates in microglandular pattern along with some single cells having obviously malignant nuclei. Small cells with scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei were found in the smears of small cell carcinoma.

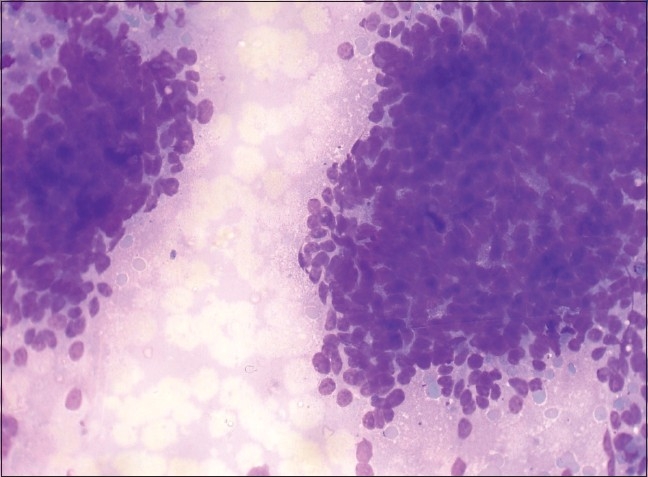

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of yolk sac tumor composed of irregular, large, cohesive three-dimensional cell balls and papillae, with infrequent single cells with abundant, vacuolated cytoplasm. (Leishman Giemsa, ×400)

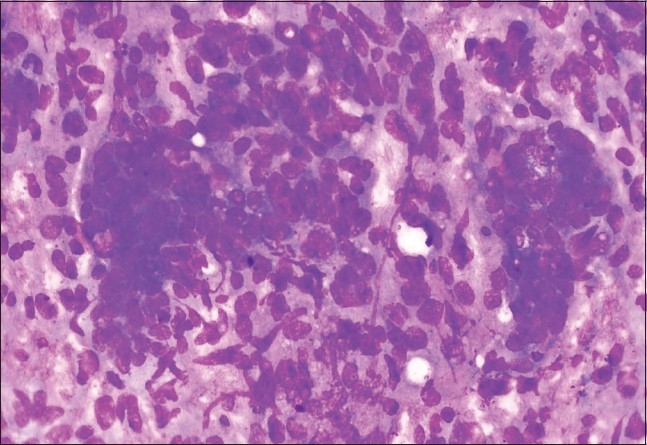

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of dysgerminoma composed of dual cell population of malignant cells and inflammatory cells, including reactive lymphoid cells with tigroid background. (Leishman-Giemsa, ×400)

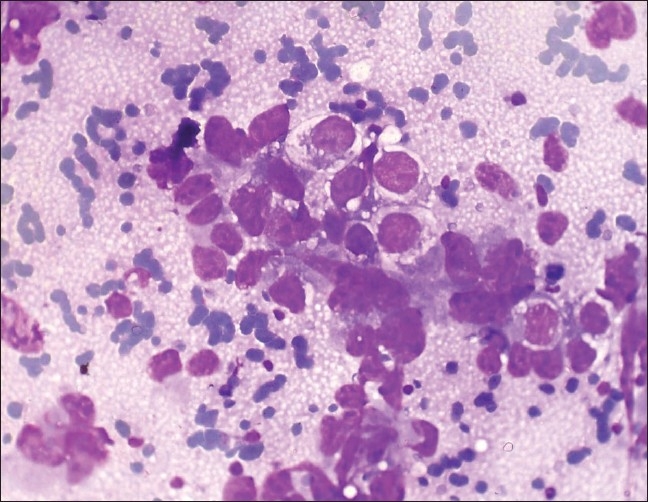

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of serous cystadenocarcinoma composed of papillary aggregates with increased cellularity, including single cells with cytological atypia. (Leishman-Giemsa, ×400)

Out of 10 benign serous cystadenomas, 8 showed the same histopathological diagnosis, but 2 came out to be borderline serous tumors. Among the cytologically diagnosed six mucinous cystadenomas, all correlated well with histopathology. Out of 18 cases diagnosed as serous adenocarcinoma, 15 cases had concordant histopathological diagnosis, 2 cases were of borderline malignancy in histopathology and a single case was reported as undifferentiated carcinoma. Among the nine cytological diagnoses of mucinous adenocarcinoma, only one proved to be a case of Krukenberg tumor and another one was borderline mucinous tumor and the rest of seven cases correlated well. It was very difficult to subclassify high-grade surface epithelial malignant tumors on cytological examination. The cases which we reported as adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified cytologically (13 cases in our series), histopathologically proved to be undifferentiated carcinoma (5 cases) high-grade serous adenocarcinoma (3 cases), endometrioid adenocarcinoma (3 cases), clear cell carcinoma (1 case) and a case of metastatic carcinoma.

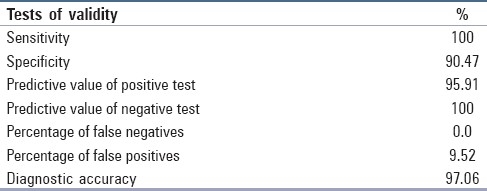

Tests of validity in our case series are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Tests of validity in our series

We found malignant cells in ascitic fluid in 16 patients having malignant ovarian tumors. There was no significant tumor cell spillage to the peritoneal cavity following FNAC. Two patients with stage IV disease had pleural effusion and examination of pleural fluid revealed malignant cell in one of them. Most of the patients with epithelial ovarian carcinomas including serous adenocarcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma had very high CA 125 level ranging from 910.5 to 3167.3 U/mL (normal laboratory level <35 U/mL). We estimated CA 125 and serum AFP by automated chemiluminescence method with ACS-180 of Bayer Healthcare. High serum AFP (range 1–10 ng/mL) correlated well with two yolk sac tumors in our series.

Discussion

The accuracy of aspiration cytology diagnosis in patients with ovarian enlargement or cancer was reported by Kjellgren et al.,[3] Geier et al.,[4] Nadji et al.[5] and Geier and Strecker.[6] In these reports, ovarian cancer was accurately identified in approximately 85-95% cases. The proportion of false-positive cytological reports in histopathologically benign cases varied from 0% to about 5%. None of these authors reported any spread of tumor cells after the procedure. We also did not have any false-positive case in our study regarding malignancy and no significant spillage of tumor cell was detected during follow-up. Ganjei[7] also commented that FNA cytology has been shown to be highly accurate in diagnosing malignant gynecological tumors and the overall accuracy was 94.5% in the differentiation between benign and malignant tumors. He concluded that the aspirated material may not only be used for diagnosis and classification of ovarian neoplasms, but may also be used for DNA analysis and detection of prognostic markers, thus providing information regarding biological behavior of the tumors.

Rao et al.[8] and others worked on the role of scrape cytology in ovarian neoplasms and its utilization for teaching pathology residents. Scrape cytology is a modification of imprint cytology and its diagnostic accuracy is better than imprint cytology. Scrapings were obtained from fresh cut surface of ovarian tumor specimens sent in 10% buffered formalin. Formalin did not interfere or produce any remarkable change in cytomorphology. Scraping of the cut surface prior to smearing facilitated the harvesting of cells. Overall diagnostic accuracy of scrape cytology was satisfactory, as 92% cases correlated well with final histopathological diagnosis.

Khan et al.[9] studied 120 patients with ovarian masses and performed USG guided FNAC in 92 benign cases. FNAC and/or imprints of surgically resected ovarian masses were done in 28 clinically suspected malignant cases. The overall sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of FNAC in diagnosis of various ovarian masses were 79.2%, 90.6% and 89.9%, respectively. They recommended the use of USG guided FNAC especially in benign ovarian cysts to avoid superfluous surgery. For diagnosis of malignancy, we also found very high sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 90.47% and diagnostic accuracy of 97.06%. Asotra et al.[10] and others reported a case of a 58-year-old postmenopausal woman with ovarian metastasis diagnosed by cytology, 6 years after the case had been operated for infiltrating duct carcinoma of the breast. On FNAC, the cells were arranged in clusters having high nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio, moderate amount of cytoplasm, vesicular nucleus with conspicuous nucleoli. On the basis of cytological features, it could not be categorized under any of the primary tumors of the ovary. A diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma was given which was confirmed on histopathological examination.

Ovarian involvement is seen at autopsy in about 10% of cases of breast cancer. The metastases are bilateral in approximately 80% of the cases and in approximately two-thirds of all cases, autopsy and surgery combined.[11] Lobular carcinomas, including those of signet ring cell type, spread to the ovary more frequently than those of ductal type.[10] The most common sites of origin of metastatic ovarian tumors include the gastrointestinal tract (stomach, colon, pancreas and appendix), breast and hematopoietic system. Several gross and microscopic features suggest the metastatic nature of the ovarian neoplasm. These include bilaterality, presence of multiple nodules of the tumor, involvement of the surface and superficial cortex of the ovary, smaller tumor size and histological features that are incompatible with a primary ovarian tumor.[12] In our series, we had one Krukenberg tumor and one metastatic adenocarcinoma.

Uguz et al.[13] studied FNAC of ovarian lesions and recommended that all available clinical, radiologic and laboratory data should be combined with FNAC features for an accurate cytodiagnosis. FNAC of borderline ovarian lesions was reported by Athanassiadou and Grapsa.[14] It was not possible to separate borderline ovarian lesions from well-differentiated cystadenocarcinomas by FNAC alone.[15,16] Diagnosis of borderline tumors was also not possible in cytology in our series. Among the five histopathologically diagnosed serous borderline tumors and one borderline mucinous tumor, two were included in benign and three in the malignant category in cytology and one had inconclusive cytodiagnosis.

One of the major objections for the use of FNAC in cystic ovarian tumors is the high percentage of inadequate samples.[17] Since the exact position of the needle is not always known, the aspirate may represent peritoneal rather then cystic fluid.[15] We found that aspirates from serous cystadenomas and mucinous cystadenomas were often hypocellular. But the cellular yield for both benign and malignant ovarian tumors was better by CT guidance.

McCluggage et al.[18] performed immunocytochemical staining of ovarian cyst aspirates with monoclonal antibody against inhibin for definite recognition of a functional cyst and exclusion of a potentially neoplastic epithelial lined cyst.

Petru et al.[19] did a comparison of three tumor markers, namely, CA 125, lipid-associated sialic acid (LSA) and NB/70K, in monitoring ovarian cancer and reported that CA 125 by itself showed equal or higher sensitivity as well as higher specificity than in combination with either LSA or NB/70K. In our series, we also found serum CA 125 above 1000 U/mL in most high-grade serous adenocarcinomas and endometrioid adenocarcinomas as well as undifferentiated adenocarcinomas.

Granados[20] extensively studied aspiration cytology of ovarian tumors and found that FNAC may provide a definitive diagnosis particularly when used in conjunction with ultrasound examination and serological markers.

Bland et al.[21] did research work on the predictors of suboptimal surgical cytoreduction in women with advanced epithelial cancer treated with initial chemotherapy and found that patients with suboptimal cytoreduction had smaller bowel-mesentery disease and disease on the liver surface on preoperative CT scan compared to the optimal surgical cytoreduction group.

FNAC of a solid ovarian mass is more useful. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of FNAC increase if an ovarian tumor is malignant.[22] In our study, we could diagnose all the malignant lesions accurately in respect of cytological criterion of malignancy, but could not categorize 13 of the high-grade surface epithelial malignant tumors. In our series, the germ cell tumors and the granulosa cell tumors were diagnosed and categorized perfectly by high cellular yield and the special cytological characteristics that were well demonstrated in Leishman-Giemsa stained cytological smears.

We found guided FNAC very useful for the detection of solid malignant ovarian tumors. The cellular yield was not satisfactory in cystic benign and borderline tumors. Excluding the unsatisfactory and inconclusive cases, the diagnostic accuracy for malignancy was very high. As we performed FNAC on patients in whom imaging findings suggested non-functional cysts, in our series, we had only 1 (1.35%) non-neoplastic cyst or lesion (hemorrhagic cyst of ovary). Except for coagulation disorders, there is practically no major contraindication.

In our study carried out in a peripheral medical college, all the patients could not afford serum marker study. Neither did all the types of ovarian malignant tumors have specific serum markers. The suspicion of malignancy was based on clinical findings, radiological observations or serum markers. Image-guided FNAC is justified as it is a relatively quick, economical and patient-friendly procedure for diagnosis of malignancy, with minimum morbidity. The procedure definitely helped the clinician in further management of the patient. The treatment of ovarian cancer is still a challenge to gynecological oncology. Three kinds of standard treatment are currently used for epithelial ovarian cancers depending upon the stage of the disease. Ovarian cancer surgery aims to remove as much of the tumor as possible. Radiation therapy uses high-energy radiation to kill cancer cells or prevent them from growing. Chemotherapy uses potent drugs to kill cancer cells or at least stopping them from dividing. For ovarian malignant germ cell tumors, surgery is required for confirmation of diagnosis, staging and treatment, followed by routine administration of adjuvant Cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Conclusion

FNAC ovary is generally a not very commonly performed procedure and onco-gynecologists insist on a surgery in most of the cases. Still FNAC ovary is being discussed for initial evaluation before treatment, for evaluation of recurrent and metastatic tumors, and for advanced inoperable malignant ovarian tumors. To improve the accuracy of the method, a close cooperation among the echoscopist, gynecologist and pathomorphologist is needed. Apart from its invaluable contribution to direct patient management, ovarian FNAC can be applied to research studies of various kinds.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Fishman DA, Bozorgi K. The scientific basis of early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer: The National Ovarian Cancer Early Detection Programme (NOCEDP) Cancer Treat Res. 2002;107:3–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3587-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young JG, Perez CA, Hoskins WJ. Cancer of the ovary. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: Principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1993. pp. 1226–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kjellgren O, Angstrom T, Bergman F, Wiklund DE. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in diagnosis and classification of ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 1971;28:967–76. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:4<967::aid-cncr2820280421>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geier G, Kraus H, Schuhmann R. Fine needle aspiration biopsy in ovarian tumors. In: DeWatteville H, et al., editors. Diagnosis and treatment of ovarian neoplastic alterations. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 1975. pp. 73–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadji M, Greening SE, Sevin BU, Averette HE, Nordqvist SR, Ng AB. Fine needle aspiration cytology in gynecologic oncology. II. Morphologic aspects. Acta Cytol. 1979;23:380–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geier GR, Strecker JR. Aspiration cytology and E2 content in ovarian tumors. Acta Cytol. 1981;25:400–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganjei P. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the ovary. Clin Lab Med. 1995;15:705–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao S, Sadiya N, Joseph LD, Rajendiran S. Role of scrape cytology in ovarian neoplasms. J Cytol. 2009;26:26–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.54864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan N, Afroz N, Aqil B, Khan T, Ahmad I. Neoplastic and nonneoplastic ovarian masses: Diagnosis on cytology. J Cytol. 2009;26:129–33. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.62180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asotra S, Sharma J, Sharma N. Metastatic ovarian tumor. J Cytol. 2009;26:144–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.62183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiyokawa T, Young RH, Scully RE. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary: A clinicopathologic analysis of 120 cases with emphasis on their variable pathologic manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:277–99. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000190787.85024.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antila R, Jalkanen J, Heikinheimo O. Comparison of secondary and primary ovarian malignancies reveals differences in their pre- and perioperative characteristics. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uguz A, Ersoz C, Bolat F, Gokdemir A, Ali Vardar MA. Fine needle aspiration cytology of ovarian lesions. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:144–8. doi: 10.1159/000326122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Athanassiadou P, Grapsa D. Fine needle aspiration of borderline ovarian lesions: Is it useful? Acta Cytol. 2005;49:278–85. doi: 10.1159/000326150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orell SR, Sterett GF, Whitaker D. Fine-needle aspiration cytology. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. Male and female genital organs; pp. 381–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kini SR. Color atlas of differential diagnosis in exfoliative and aspiration cytopathology. 1st ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1999. pp. 423–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Onsurbe P, Ruiz Villaespesa A, Sanz Anquela JM, Valenzuela Ruiz PL. Aspiration cytology of 147 adnexal cysts with histologic correlation. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:941–7. doi: 10.1159/000328368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCluggage WG, Patterson A, White J, Anderson NH. Immunocytochemical staning of ovarian cyst aspirates with monoclonal antibody against inhibin. Cytopathology. 1998;9:336–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1998.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petru E, Sevin BU, Averette HE, Koechli OP, Perras JP, Hilsenbeck S. Comparison of three tumor markers-CA-125, lipid-associated sialic acid (LSA), and NB/70K-in monitoring ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;32:181–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90037-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granados R. Aspiration cytology of ovarian tumors. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1995;7:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bland AE, Everette EN, Pastore LM, Anderson WA, Taylor PT., Jr Predictors of suboptimal surgical cytoreduction in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer treated with initial chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:629–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganjei P, Dickinson B, Harrison TA, Nassiri M, Lu Y. Aspiration cytology of neoplastic and non-neoplastic ovarian cysts: Is it accurate? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1996;15:94–101. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]