Abstract

Background

Chronic pain patients often have comorbidities, including social habits such as tobacco abuse, they use to cope with pain states. This study tested the hypothesis that physician activism, communication, and interest in smoking cessation can reduce or eliminate tobacco use.

Methods

We developed a survey to evaluate patients' smoking habits and to determine if active physician participation changed these habits.

Results

We surveyed a total of 112 patients. Of the 56 smokers, 59% reported they had previously tried to stop. Smokers initially reported smoking 25.5 cigarettes per day for an average of 18.4 years. After receiving monthly physician messages regarding smoking, 51 of the smokers (91%) reported a reduction. These patients reported an average of 7.2 cigarettes smoked per day. Of the smoking patients, 79% indicated that they were influenced to reduce or stop smoking at the clinic, and 86% recalled that they heard specific statements from their doctor in the clinic. After reducing the number of cigarettes smoked, patients reported breathing better (68%), feeling better (66%), and experiencing less pain (34%).

Conclusion

Physician influence correlated with smoking reduction in this study.

Keywords: Nicotine, pain management, smoking, tobacco abuse

INTRODUCTION

Despite the efforts of healthcare providers, an epidemic of tobacco abuse exists throughout the United States and across the globe. This problem is quite evident in the pain population, where smoking is common as documented in many studies.1,2 Although the exact pathophysiology of how smoking modulates the pain response remains unclear, substantial evidence supports the concept that smokers not only have a higher incidence of chronic pain but also report higher pain intensity scores.1 While cigarettes include more than 4,000 chemicals, nicotine specifically has been shown to modulate the pain response in both animal and human models.3-9 Nicotine exposure has a prominent effect on both the central and peripheral nervous systems through binding of pentameric ionic nicotine acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) that are permeable to Na+, Ca2+, and K+.1,10 Postsynaptic activation results in direct excitatory neuronal effects via the cationic channel.1 Presynaptic nAChR activation has been shown to influence the release of other neurotransmitters, including dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, serotonin, histamine, and norepinephrine.1,10,11

In both animal and human studies, naive nicotine exposure has been shown to have paradoxical analgesic properties. This antinociceptive effect is thought to be partially mediated by the endogenous opioid system. This claim is reinforced by animal studies that assessed pain perception in rats by measuring tail flicks in response to hot plate exposure.1,4 Rats administered subcutaneous nicotine had an increased threshold to pain compared to those rats not administered nicotine.1,4 However, the antinociceptive effects of nicotine were blocked by the administration of either the centrally acting nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine or the opioid antagonist naltrexone.1,5

In humans, studies have demonstrated that nicotine administration via nasal spray or transdermal patch reduces pain sensitivity in both smokers and nonsmokers.1,6,7 In a placebo-controlled trial of nonsmoking female patients undergoing uterine surgery via a low transverse incision, nicotine enhanced morphine analgesia.1,8 Patients who received a single 3 mg dose of nicotine nasal spray before emergence from general anesthesia reported lower pain scores during the first hour after surgery, used half the amount of morphine, and reported less pain 24 hours after surgery.1,8

However, patients with chronic nicotine exposure fail to show the same beneficial analgesic effect. In the study by Turan et al9 of a female patient population consisting predominantly of chronic smokers, subjects reported no decrease in postoperative pain with nicotine patches after undergoing abdominal hysterectomies. Positron emission tomography has revealed that humans who smoke have greater densities of high affinity nAChRs in several brain regions compared with nonsmokers and ex-smokers.1,12 Thus, it appears that chronic exposure can induce changes in receptor concentrations and could be responsible for mediating or modulating nociceptive responses to stimuli, subsequently resulting in tolerance and mitigating the analgesic properties of nicotine.

The relationship between chronic pain and smoking is detailed in a meta-analysis by Shiri et al2 of 40 studies that reviewed the relationship between cigarette smoking and chronic lower back pain. Their analysis showed that compared to people who have never smoked, former and current smokers had a higher prevalence of low back pain in the past month and in the past 12 months and were more likely to seek care for low back pain and chronic low back pain. They also found that current smoking had the strongest association with debilitating back pain. Their research also revealed a dose-response relationship between the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the prevalence of chronic low back pain.2

Based on data published in previous studies, lower pain scores seen in nonsmoking patients suggest that smoking cessation among chronic smokers may result in less pain.1,2 Also, many psychological, socioeconomic, biological, and medical factors may play a role in the complex relationship between chronic pain and smoking. The present study aimed to ascertain whether dedicated physician reinforcement promoting smoking cessation could have a significant positive effect on both smoking prevalence and patient well-being.

METHODS

Study Design

This study used a voluntary, random survey of chronic pain patients who either did or did not previously receive tobacco cessation counseling from their pain practitioner to assess the effectiveness of physician interest and activism in their tobacco habits.

Sample Characteristics

Patients at an urban pain clinic who were seen by a board-certified pain specialist received the survey at their monthly clinic visit. Patients were not discriminated against based on their smoking status, diagnosis, or age.

Intervention Conditions

All pain patients who smoked tobacco on their initial visit had tobacco added to their problem list. At each monthly appointment, the pain practitioner gave these patients 3 messages: (1) every cigarette has more than 50 poisonous chemicals, (2) smoking cigarettes will shorten your lifespan, and (3) your current diagnosis will not improve (ie, your pain will not lessen) if you continue to smoke.

Data Collection

All established pain clinic patients were given the opportunity to participate in this study. From December 2010 to March 2011, a total of 112 pain patients received the survey. Of these patients, 56 patients were current smokers, 49 were nonsmokers, and 7 did not complete the survey.

Statistical Analysis

Mean was used to ensure no bias between the populations (smokers and nonsmokers) in terms of diagnosis and age. Standard deviation and standard error were used to evaluate the effectiveness of physician activism in tobacco cessation.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

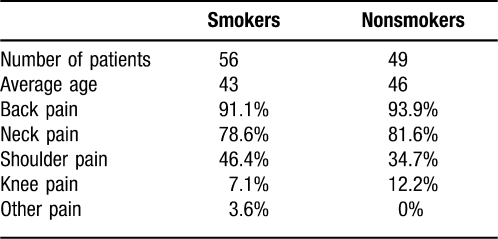

The average age of smokers and nonsmokers was similar, at 43 years and 46 years, respectively (Table). Both groups also had similar diagnoses, with back pain being the most common reason for visiting the pain clinic (91% of smokers and 94% of nonsmokers), followed by neck pain (79% and 82%), shoulder pain (46% and 35%), and knee pain (7% and 12%).

Table.

Demographics of Pain Patients Taking the Survey

Smokers initially reported smoking an average of 25.5 cigarettes a day for an average of 18.4 years. Of the smokers, 59% had previously tried to quit smoking.

Change in Tobacco Smoking Habits

A total of 51 (91%) patients reported a reduction in smoking cigarettes after receiving monthly messages from their pain clinic physician. Only 5 patients did not report a reduction; however, when viewing the actual number of cigarettes smoked a day, 1 of those 5 patients actually had reduced his or her smoking, bringing the total number of smokers who reduced their smoking to 52 (93%). At the time of the survey, the smokers' average number of cigarettes per day had decreased from 25.5 to 7.2 cigarettes per day (Figure 1). Of these 52 smokers, 79% indicated that they were influenced to reduce or stop smoking at the pain clinic.

Figure 1.

Number of cigarettes smoked on initial visit and after physician counseling.

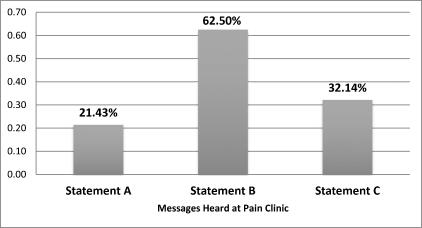

Most Effective Message

Of the smokers, 86% recalled that they heard specific statements from their physician at the pain clinic regarding facts about smoking. The most influential statement in convincing people to reduce smoking was statement 2, that smoking will shorten one's lifespan, with 63% of smokers selecting it. At 32%, statement 3 was next: Your pain will not improve if you continue smoking. The least effective message, with 21% of smokers choosing it, was statement 1: A cigarette includes more than 50 poisons (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Message preference related to continued smoking and influence in cessation. (A: Every cigarette has more than 50 poisonous chemicals. B: Smoking cigarettes will shorten your lifespan. C: Your current condition will not improve if you continue to smoke.)

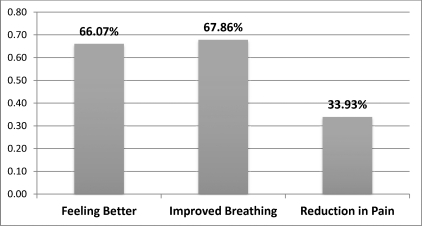

Effects of Reducing Smoking

After patients decreased the amount they smoked daily, they reported breathing better (68%), feeling better (66%), and having less pain (34%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Patient-reported benefits from smoking reduction and cessation.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate a significant reduction in smoking for acute and chronic pain patients. Furthermore, of the physician statements presented during each patient visit, the one that resonated most was that smoking will shorten one's lifespan.

Prevention is the best cure. This simple phrase is often lost in all of the technological advancements and breakthroughs that characterize medicine today. Previous observational studies have demonstrated that few smokers entering chronic pain treatment successfully quit, even when offered efficacious tobacco intervention services.13 However, the results of this cohort study show that persistence on the part of the physician can actually result in a significant reduction in both the amount and prevalence of nicotine consumption among a patient population in a relatively short amount of time. Patients in the present study were offered a multitude of options for smoking cessation, including prescriptions for varenicline, education about over-the-counter nicotine patches and supplements, electronic cigarettes, and self-cigarette titration by smoking 1 less cigarette each day. The present study indicates that physician interest and effort in smoking cessation are paramount for success. To that end, tobacco use was listed on each patient's clinic note to prompt physician discussion. Although the results of this study only showed a moderate decrease in pain symptoms, we anticipate a more significant impact on pain scores in a study of longer duration.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 1 in 5 Americans smokes cigarettes and that at least 1 in 10 nonsmokers is exposed to secondhand smoke.14,15 The medical results of nicotine use demand millions of dollars in government resources annually. Because both chronic pain and smoking are highly prevalent in the United States, more research is needed to better establish the link between the two. Our study demonstrates that clinicians can positively impact the success of patient smoking-cessation programs and thereby improve a patient's quality of life and also help reduce smoking's burden on the American healthcare system. We hope our study inspires further research and demonstrates the value of physician intervention in smoking cessation.

CONCLUSIONS

One of the most common complaints in clinical practice is pain. Many types of physicians other than pain specialists manage patients with underlying chronic pain. We currently have an epidemic of tobacco abuse associated with pain states, as well as poor nationwide cessation outcomes. Regardless of physician specialty, our results clearly demonstrate that using this type of protocol can significantly affect smoking cessation.

In summary, the present investigation demonstrates that active physician participation in a systematic and methodical manner can result in a significant reduction of smoking prevalence in pain patients. Active teaching of this practice to clinicians, trainees, medical students, and other health professionals should be encouraged to help reduce smoking worldwide.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shi Y, Weingarten TN, Mantilla CB, Hooten WM, Warner DO. Smoking and pain: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology. 2010 Oct;113(4):977–992. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ebdaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Viikari-Juntura E. The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2010 Jan;123(1):87.e7–87.e35.. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin T. What's in a cigarette? About.com, November 15, 2010. http://quitsmoking.about.com/cs/nicotineinhaler/a/cigingredients.htm. Accessed 1 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tripathi HL, Martin BR, Aceto MD. Nicotine-induced antinociception in rats and mice: correlation with nicotine brain levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982 Apr;221(1):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons CT, Cuellar JM, Moore JA, et al. Nicotinic receptor involvement in antinociception induced by exposure to cigarette smoke. Neurosci Lett. 2005 Dec 2;389(2):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamner LD, Girdler SS, Shapiro D, Jarvik ME. Pain inhibition, nicotine, and gender. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998 Feb;6(1):96–106. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins KA, Grobe JE, Stiller RL, et al. Effects of nicotine on thermal pain detection in humans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994 Feb;2(1):95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flood P, Daniel D. Intranasal nicotine for postoperative pain treatment. Anesthesiology. 2004 Dec;101(6):1417–1421. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200412000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turan A, White PF, Koyuncu O, Karamanliodlu B, Kaya G, Apfel CC. Transdermal nicotine patch failed to improve postoperative pain management. Anesth Analg. 2008 Sep;107(3):1011–1017. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31816ba3bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taly A, Corringer PJ, Guedin D, Lestage P, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009 Sep;8(9):733–750. doi: 10.1038/nrd2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotti C, Clementi F. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2004 Dec;74(6):363–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhin AG, Kimes AS, Chefer SI, et al. Greater nicotinic acetylcholine receptor density in smokers than in nonsmokers: a PET study with 2-18F-FA-85380. J Nucl Med. 2008 Oct;49(10):1628–1635. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.050716. Epub 2008 Sep 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosselin MH, Mahoney MC, Cummings KM, et al. Evaluation of an intervention to enhance the delivery of smoking cessation services to patients with cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2011 Sep;26(3):577–582. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008 Nov 14;57(45):1221–1226. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008 Nov 28;57(47):1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Disparities in secondhand smoke exposure—United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008 Jul 11;57(27):744–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]