Abstract

Background

The interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has increased during the past decade and the attitude of the general public is mainly positive, but the debate about the clinical effectiveness of these therapies remains controversial among many medical professionals.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the existing literature utilizing different databases, including PubMed/Medline, PSYNDEX, and PsycLit, to research the use and acceptance of CAM among the general population and medical personnel. A special focus on CAM-referring literature was set by limiting the PubMed search to “Complementary Medicine” and adding two other search engines: CAMbase (www.cambase.de) and CAMRESEARCH (www.camresearch.net). These engines were used to reveal publications that at the time of the review were not indexed in PubMed.

Results

A total of 16 papers met the scope criteria. Prevalence rates of CAM in each of the included studies were between 5% and 74.8%. We found a higher utilization of homeopathy and acupuncture in German-speaking countries. Excluding any form of spiritual prayer, the data demonstrate that chiropractic manipulation, herbal medicine, massage, and homeopathy were the therapies most commonly used by the general population. We identified sex, age, and education as predictors of CAM utilization: More users were women, middle aged, and more educated. The ailments most often associated with CAM utilization included back pain or pathology, depression, insomnia, severe headache or migraine, and stomach or intestinal illnesses. Medical students were the most critical toward CAM. Compared to students of other professions (ie, nursing students: 44.7%, pharmacy students: 18.2%), medical students reported the least consultation with a CAM practitioner (10%).

Conclusions

The present data demonstrate an increase of CAM usage from 1990 through 2006 in all countries investigated. We found geographical differences, as well as differences between the general population and medical personnel.

Keywords: Alternative medicine, complementary medicine

INTRODUCTION

As Western medicine has experienced an ever-growing expansion of scientific knowledge, basic science research, and technology, the interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has also increased dramatically over the past decade. Kessler et al1 stated that lifetime prevalence of CAM therapy use in the United States has increased steadily since 1950. In fact, recent studies have shown that CAM has increasingly been accepted in the United States2-4 and all over the world.5-8 In 1999, approximately 28.9% of respondents reported using at least one form of complementary medicine. Although these numbers have been increasing in recent years,4 the debate about the clinical effectiveness of unconventional methods has been controversial among many medical professionals. However, the attitude of the general population toward CAM is generally positive. Although few scientific data exist for much of the discipline, CAM has evolved into a successful, commercially available business throughout the world. Additionally, journals focused on CAM, along with recent basic and clinical science research, have improved the understanding of the benefits gained from these various therapies and modalities.

In most countries, CAM is not covered by national insurance systems, and users pay almost all costs out of pocket. This willingness to pay reflects the public's general acceptance of CAM and also suggests that CAM therapies have benefits that outweigh their costs. Eisenberg et al2 reported that estimated expenditures for alternative medicine professional services increased by 45.2% between 1990 and 1997 and were conservatively estimated at $21.2 billion in 1997, with at least $12.2 billion paid out of pocket. This amount exceeded the 1997 out-of-pocket expenditures for all hospitalizations in the United States. A national health survey in 2007 revealed that more than $34 billion is spent on CAM annually in the United States. In Germany, where some forms of CAM are covered by insurance, costs for alternative therapies in 2000 accounted for about one-tenth of expenditures on general medical treatments.9

The significance of these numbers indicates that CAM is attracting more and more attention within healthcare. Therefore, it is not surprising that the number of physicians with specific training in CAM therapies is continually growing. In 1996, for example, Vienna, Austria, had 3,717 practice-based physicians of whom 1,206 were general practitioners (GPs) and 2,511 were medical specialists. More than 330 of them had at least 1 training experience in CAM, equivalent to 9% of all GPs.10 In 1998, 801 GPs were estimated to have training in at least 1 method of CAM, amounting to 18% of all GPs. This change represents an increase of 136% over a 2-year period.11

Many studies throughout the world have previously evaluated the use and acceptance of CAM. This survey aims to provide an overview of the utilization of CAM. The role of physicians and medical personnel concerning CAM is also of interest. However, this study is not meant to investigate the clinical effectiveness of CAM in general or the effectiveness of individual therapies. Specifically, we set out to determine the prevalence of CAM with regard to geographic differences as well as related cultural and religious aspects. In addition, we sought to discover which forms of CAM are the most widespread and the most commonly used. Third, we aimed to reveal who uses CAM most frequently with regard to sexual, cultural, social, and socioeconomic characteristics. Fourth, we hoped to determine the medical conditions for which CAM is most frequently used. Finally, we intended to discern any regional differences in CAM utilization; differences related to the acceptance of CAM among doctors, nurses, students, and other medical staff; and the prevalence of bias among medical personnel.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic search of the existing literature using PubMed/Medline, PSYNDEX, PsycLit, and other databases. In PubMed we focused on CAM via the search subset limiter “Complementary Medicine.” We also searched two other engines—CAMbase (www.cambase.de) and CAMRESEARCH (www.camresearch.net)—to find publications not indexed in PubMed. Institutional review board approval was not requested.

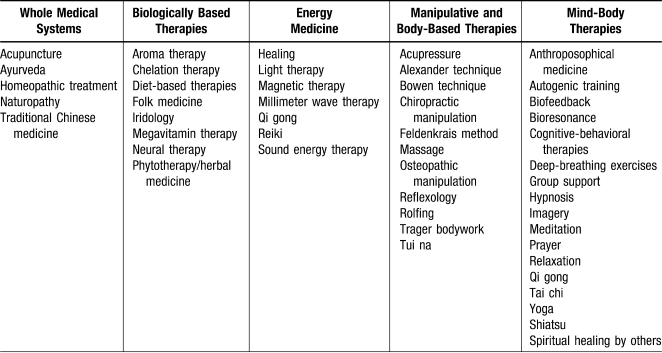

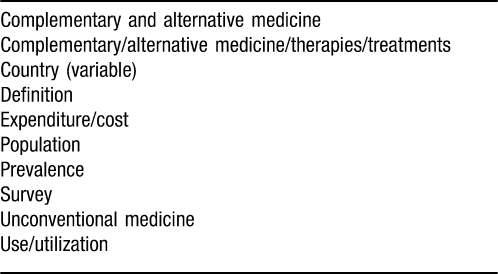

We categorized the complementary methods into five categories (Table 1) and conducted searches using the keywords listed in Table 2 that we interconnected systematically and entered in English as well as German. Because data for German-speaking countries were not always indexed in the above-mentioned databases, we searched the internet and accessed governmental and country-specific statistical websites to reveal publications or reports in the grey literature. Using the abstracts of publications as a guide, we sorted the studies by relevance and accessed the full text.

Table 1.

Categorization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies

Table 2.

Keywords Used for Data Research

We categorized the resulting literature according to either the country-specific utilization of CAM domain or the use of CAM by the physician/medical professional. We read all papers in full and examined the references for further relevant contributions. Inclusion criteria for the papers included a publication date after 1990, availability of full text, identification of sample size in the study, inclusion of at least 3 CAM methods, and specification of the percentage or number for total utilization as well as for individual CAM therapies.

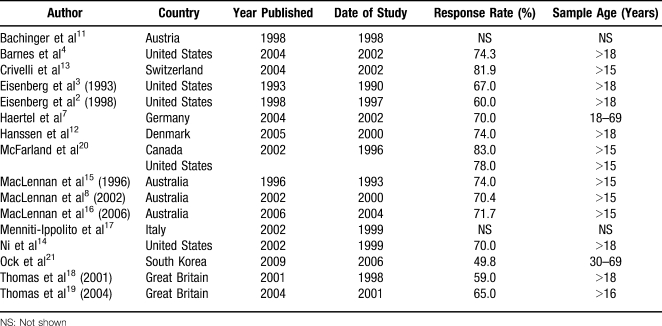

With regard to the country-specific utilization of CAM, we examined the search results using the terms listed in Table 2; if they met the above criteria, we included them in this study. Whenever possible, we attempted to include follow-up studies to provide a continuum of the development of CAM utilization. If such information was not available, we attempted to locate comparable data from the same country. An overview of the publications we examined and used in this review is provided in Table 3. Because Hanssen et al12 included relevant data from 3 Scandinavian countries (all of Denmark and Norway and Stockholm County in Sweden), these data were adopted for the present study. The study conducted by Crivelli et al13 compared the findings of two different years (1997 and 2002), but in the year 1997 only 2 forms of CAM were examined; therefore the data from 1997 were not considered. Additionally, we used the search terms medical personnel, (general) physician, students, CAM, unconventional medicine, perceptions, attitudes, views, and knowledge—in English and in German—to identify articles about views and perceptions of CAM among medical personnel.

Table 3.

Studies Included to Determine General Prevalence of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

We read all of the papers in full and collected the date of the publication, the date of survey administration/data collection, the target population/country, the final sample size, and the response rate. Subsequently, we recorded the percentage of the sample reporting CAM use, therapies/methods of CAM, the percentage of the sample reporting using a particular type of CAM, medical conditions treated with CAM, and the reasons for CAM utilization.

RESULTS

With regard to the country-specific utilization of CAM, the search revealed 16 papers2-4,7,8,11-21 that met the scope criteria (Table 3). Sample sizes included at least 1,000 respondents aged 15 years and older; 6 studies included more than 15,000 persons. The studies examined 10 different countries, and follow-up research was found for 2 nations (Australia and the United States).

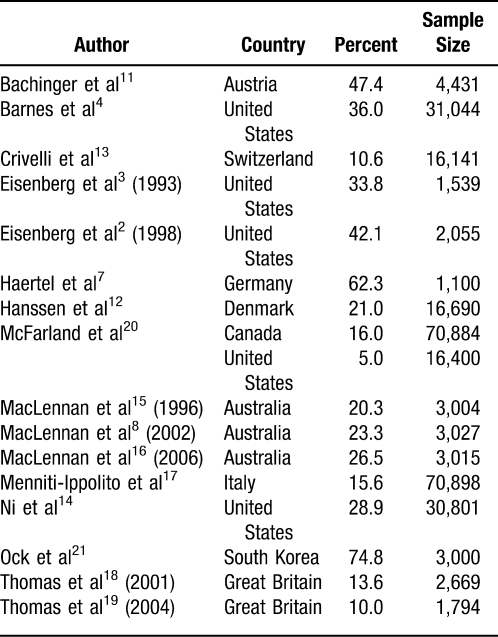

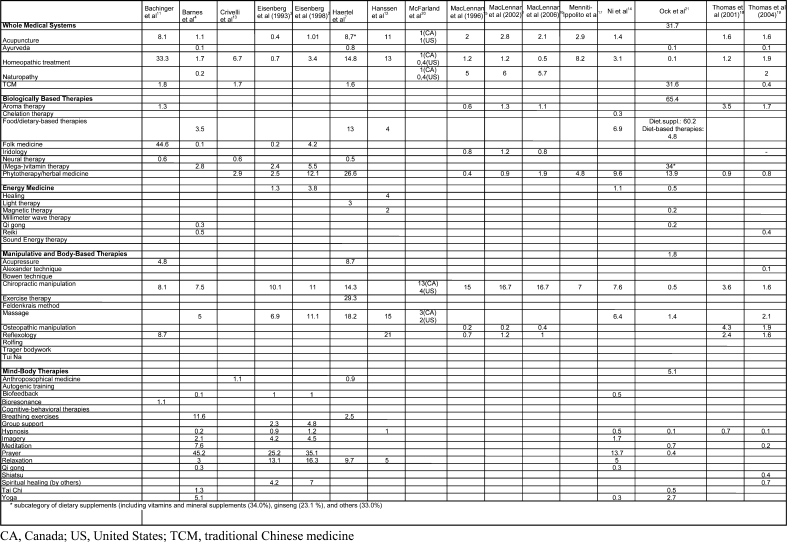

The results of the prevalence findings for each of the included studies are depicted in Table 4. Findings range between 5.0%20 and 74.8%.21 One study failed to report the time period of CAM utilization,11 and Menniti-Ippolito et al17 researched CAM utilization over the prior 2 years; all other studies referred to CAM use over a 12-month period. With the exception of Ni et al14 and Ock et al,21 the findings listed in Table 4 did not include the use of prayer.

Table 4.

Prevalence of at Least One Form of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

In 1990, 36.3% of CAM users had visited a practitioner in the past 12 months. By 1997, prevalence had increased by 10% to 46.3%. Crivelli et al13 differentiated between visits to a CAM therapist and visits to a medical doctor, finding that 42.9% of respondents had used CAM provided by a physician, 32.5% had consulted a CAM therapist, and 24.6% had received CAM by another kind of provider or gave no details.

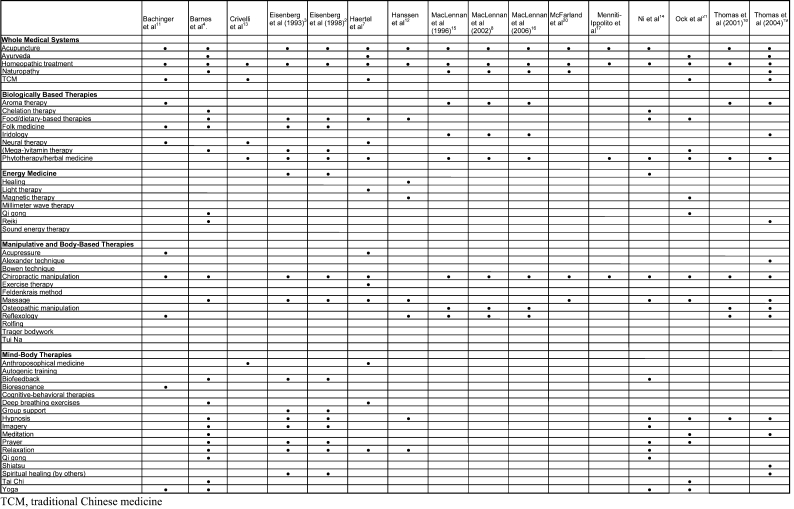

The various forms of CAM examined by the authors are listed in Table 5.2-4,7,8,11-21 Homeopathic treatment (16 times), acupuncture (14 times), chiropractic manipulation (14 times), and phytotherapy/herbal medicine (12 times) were the most frequently surveyed therapies. Energy medicine was the subgroup least explored.

Table 5.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies Examined (by Author)

Table 6 presents the prevalence findings by percentage for every therapy. Because the studies allowed multiple answers, the totals listed in Table 6 are greater than the overall findings for CAM utilization. Table 6 highlights the 3 most used therapies (excluding prayer) found by the different authors. Chiropractic manipulation was found 9 times among the 3 most used therapies, followed by phytotherapy/herbal medicine (6 times), massage (6 times), and homeopathy (5 times). In comparison to other included studies, we found a significantly higher prevalence of acupuncture and homeopathic treatment among the European studies.

Table 6.

Prevalence Findings (by Author)

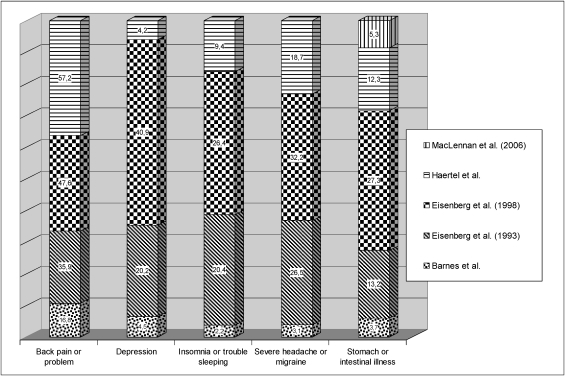

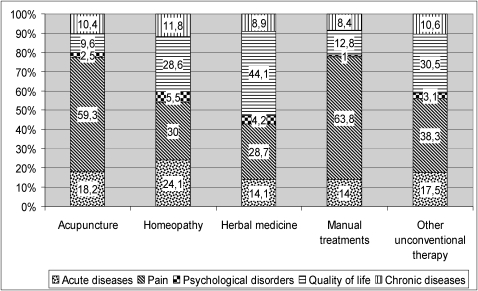

Barnes et al,4 Eisenberg et al,2,3 Haertel et al,7 and MacLennan et al16 investigated the medical conditions treated with CAM. A comparison of the findings revealed the top 5 medical conditions for which CAM was used most often (Figure 1): back pain or back problems, depression, insomnia or trouble sleeping, severe headache or migraine, and stomach or intestinal illness. Menniti-Ippolito et al17 examined the utilization of different therapies in respect to these 5 medical reasons (Figure 2). Acupuncture and manual treatments were primarily used to treat pain. Herbal medicine was used in 44.1% of cases to improve the quality of life, and homeopathy “was not associated with any specific health condition.”17

Figure 1.

Reasons for complementary and alternative medicine utilization.

Figure 2.

Reported medical reasons for unconventional therapy use.

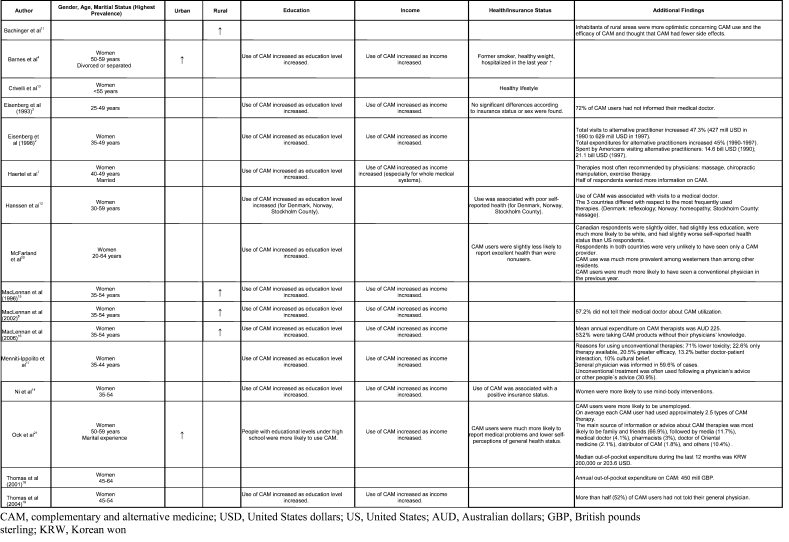

With regard to user profile, Table 7 highlights some findings by a majority of authors, who discovered that women were more likely to use CAM than men. Also, higher levels of education were found predictive in 12 studies and higher income in 11 studies.

Table 7.

Predictors of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Utilization (by Author)

A search for studies concerning the views, knowledge, and attitudes of medical personnel revealed 10 publications.22-31 Three main groups of medical professionals were identified and covered by the surveyed studies: GPs and hospital doctors, nurses, and students. Except for the study undertaken by Hyodo et al,23 authors found positive perceptions toward CAM in all occupational groups. Baugniet et al24 examined the views of 5 types of students. Medical students were the most critical toward CAM. Compared to students of other professions (eg, nursing students: 44.7%, pharmacy students: 18.2%), medical students reported the least consultation with a CAM practitioner (10%). They also stated the lowest interest in CAM training and were, together with pharmacy students, more likely than the other health professions students to view traditional scientific forms of evidence as necessary before accepting CAM therapies. Because medical students also reported the least amount of education about CAM, the authors claimed that “educational exposure to CAM was correlated with the perceived usefulness of CAM.”24

DISCUSSION

The wide range of utilization of CAM among the population may be because of the lack of consensus in defining CAM, but the findings suggest that a high proportion of the population uses CAM. In general, the average prevalence of CAM was 32.2%. Because the studies were heterogeneous, the average was only calculated to give a rough estimate of proportions. The follow-up studies in particular found a steady increase in CAM use. Eisenberg et al2 stated that between 1990 and 1997 the use of CAM increased from 33.8% to 42%. In 2002, a review by Germany's Robert Koch Institut9—the central federal institution responsible for disease control and prevention—presented findings from standardized surveys conducted by the Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach in 1970, 1997, and 2002. The surveys show a steady increase of CAM utilization since 1970. In 1970 about 14% of respondents had used some form of CAM over the past 3 months; this amount doubled to 28% in 1997 and ascended to 34% in 2002. Wolf et al32 reviewed the situation in Switzerland and found that the average prevalence of CAM was 49%, and Kessler et al1 stated that 67.7% of their American sample had used at least one form of CAM in their lifetime.

Additionally, these studies and the review by the Robert Koch Institut revealed that acupuncture and homeopathy are used more often in European countries than in the United States and Canada. Additional research comes from the World Health Organization's Global Atlas of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine in 2005.33 This atlas is a review-based overview of the CAM situation across the world and is at present one of the most reliable studies on CAM. The atlas substantiates the findings that chiropractic manipulation, homeopathy, phytotherapy/herbal medicine, and massage were the most used therapies. If prayer had been considered in the present study, it would certainly be among the most used therapies. When study authors examined the use of prayer, it was in at least the top 3 and most times showed the highest prevalence. Also relevant was the sparse research on energy medicine methods; few studies examined their prevalence. Therefore, little is known about utilization. It is difficult to provide an explanation for this lack of interest, but whenever one of these methods was examined, it ranked among the least used.

A closer look at the follow-up studies by Eisenberg et al2,3 showed an increase in the usage of nearly every therapy. Specifically, this increase applied to herbal medicine, massage, megavitamins, self-help groups, folk medicine, energy healing, and homeopathy. Referring to the studies undertaken by MacLennan et al,8,15,16 Eisenberg et al stated, “there has been a steady increase in use of CAM therapists by the South Australian public over the past 10 years.” Although prevalence rates for the utilization of CAM therapists between 2000 and 2002 (Table 4) were declining, the authors found an increase in visits over the past 10 years to herbal and other therapists (prevalence for the Other Therapists group: 1.8% [1993], 1.2% [2000], and 4.8% [2004]). Table 6 shows that prevalence rates increased over the past 10 years. Additionally, Crivelli et al13 stated

…a higher utilization of a CAM therapy is related to: a healthy and health preventive lifestyle (sports, abstinence of alcohol); lack of a general physician; no use of prescribed medications and vitamins over the last week; no medical treatment concerning rheumatism, heart disorders, allergic coryza or other allergies as well as mental breakdown or depression over the last 12 months; no physical or psychological problem since over 12 months; no headache, facial pain, general weakness or fatigue over the last 4 weeks; complete abandonment of influenza vaccination; a good up to very good self reported health status. In general users of a CAM therapist seem to be in a better health than users preferring a physician as their CAM provider.

Ozcakir et al25 found a lack of education in CAM: 96.5% of the physicians they studied had received no education in CAM. However, 74.4% of these physicians wanted some education on the subject. Although knowledge levels were low, about half of physicians (51%) believed in the efficacy of CAM. DeKeyser et al,26 Newell et al,27 Münstedt et al,28 and Wahner-Roedler et al29 also found a lack of education and knowledge about CAM. Perkin et al30 claimed that “in each group a majority felt that alternative medicine should be taught as a topic course during a medical student's training (medical students 84%, GPs 75%, hospital doctors 60%).”

Similarly, the Richardson et al31 study examined the reasons for communication gaps between physicians and patients about CAM and found that patients and physicians had different reasons for nondisclosure. “Physicians believed patients felt CAM discussions were unimportant and physicians would not understand, discontinue treatment, discourage or disapprove of the use. Patients attributed nondisclosure to their uncertainty of its benefit and never being asked about CAM.” This finding was consistent with the results of Wahner-Roedler et al29 who noted that “more than half the physicians (63%) stated that the patient initiated the discussion about benefits and risks of CAM therapy.”

Prevalence findings by Crivelli et al,13 Thomas et al,18,19 and MacLennan et al8,15,16 are based on CAM provided by therapists. Studies undertaken by Bachinger et al,11 Barnes et al,4 Haertel et al,7 Hanssen et al,12 McFarland et al,20 Menniti-Ippolito et al,17 Ock et al,21 and Ni et al14 did not differentiate between self-care and the use of a CAM therapist. Eisenberg et al2,3 distinguished between use under the supervision of a practitioner of alternative therapy and use without such supervision.

Because all of the studies allowed multiple answers in the study methodology, a recalculation was not possible. Therefore, the best overall prevalence with prayer included can only be specified for Barnes et al4: 62%. Compared to the findings without prayer, this figure demonstrates an increase in utilization of 26%. Both follow-up studies2,16 found an increase in prevalence rates. Eisenberg et al2 reported an increase of 8.3% in CAM utilization between 1990 and 1997. MacLennan et al16 showed a continuing rise of CAM prevalence among the Australian population between 1993 and 2004 (1993: 20.3%, 2000: 23.3%, and 2004: 26.5%).

The identification of a user profile was another key question of the present study. Studies on general utilization found similar results. The most predictive factors for CAM utilization were sex, age, and education. The majority of the publications we reviewed showed a significantly higher utilization of CAM among women. Also, users tended to be middle aged and better educated. These findings are common to the results of several other authors34-41 and therefore might be the most predictive factors of CAM utilization. Also, several studies found that higher income levels were associated with a higher utilization of CAM, while the impact of marital status and health status was inconclusive. Although separation and poor health tend to be associated with a higher CAM utilization, these factors might be weak predictors.

Astin et al42 investigated other possible predictors of alternative healthcare use. The authors found that membership in the so-called cultural creatives—people at the leading edge of cultural change and characterized by their commitment to causes such as feminism, environmentalism, spirituality, personal growth, and a love of the foreign and exotic—predicted CAM utilization. In a review of the literature on beliefs involved in the use of CAM, Bishop et al43 found CAM users to have more active coping styles and to be more interested in making treatment decisions. Personal characteristics such as personality and coping skills were also reported by Honda et al,44 Huber et al,45 Spadacio et al,46 and Kersnik et al.36

LIMITATIONS

The limitations of this work are mostly the result of difficulties in interpreting the differing methodologies of the sources we reviewed. The lack of a uniform definition of CAM and the great diversity of different methods, therapies, and dogmas of CAM made the studies difficult to compare. Even if definitions had been standardized, there was no guarantee of a solid basis for comparison. Similarly, the authors examined different forms of CAM, used different names, created their own categories, or combined different therapies. Another distinction that was not always evident in the methodological structure of the studies was whether medicines and self-care were included in addition to therapies received from a CAM practitioner. Some studies only asked about therapies used by a practitioner, whereas other studies did not differentiate. If both were cited, then self-care was excluded for the present study. A third limitation is the specified period of the surveys. Although studies of the general utilization of CAM mostly surveyed the prior 12 months, studies with smaller sample sizes often did not; others examined lifetime use or current usage. Some surveys failed to state the time period for the results. Nearly every study cited in our evaluation used different time ranges and methodologies (some in excess of one year).

Also, the inclusion of prayer within the scope of CAM made a significant difference in the CAM utilization results. Studies with forms of prayer included had significantly higher prevalence findings than studies with prayer excluded. Whenever possible, prayer was excluded for the present survey.

At times, similar types of CAM were combined (eg, chiropractic manipulation/osteopathic manipulation). In these cases, data were entered for both forms of CAM. Some authors created their own subgroups and allocated several forms of CAM to them. Results specified only for an entire subgroup were not considered in the present study, nor were results that listed several forms of CAM under the term Other. Whenever possible, we attempted to include all the methods/therapies listed by an author. Because CAM consists of a great diversity of methods, and because these studies examined various forms of CAM, we could not always account for all specific methods (eg, different kinds of herbs). Finally, if findings were calculated for the entire population of a specific country, then prevalence data were recalculated to the sample size (using the specified percent) for the present study.

PROSPECTS AND VISIONS

The story of CAM cannot be considered a transient phenomenon—it must be considered a sustainable need of the population. The prevalence of CAM is high and will constantly increase with the health awareness of the population. The reasons for CAM utilization are complex and include the costs of traditional therapies, a desire for a more holistic approach to treatment, the integration of CAM in therapy decisions, and dissatisfaction with current therapies. Uniform nomenclatures, definitions of CAM, and therapy protocols would provide better transparency and understanding. More research would support the further integration of CAM into conventional medicine as the benefits of these therapies are continually identified and published in scientific journals. For example, a study published last year showed a significant reduction in blood pressure and heart rate after deep tissue massage.47 Therefore, more education about CAM is needed to prepare students, the next generation of physicians, to meet the requirements of their future patients.

CONCLUSIONS

The data from this review demonstrate an increase of CAM usage from 1990 through 2006 in all countries investigated.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care and Systems-Based Practice.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 135(4):262–268. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00011. 2001 Aug 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 280(18):1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. 1998 Nov 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 328(4):246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. 1993 Jan 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. (343):1–19. 2004 May 27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris P, Rees R. The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use among the general population: a systematic review of the literature. Complement Ther Med. 8(2):88–96. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0353. 2000 Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher P, Ward A. Complementary medicine in Europe. BMJ. 309(6947):107–111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6947.107. 1994 Jul 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haertel U, Volger E. [Use and acceptance of classical natural and alternative medicine in Germany—findings of a representative population-based survey] Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2004 Dec;11(6):327–334. doi: 10.1159/000082814. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. The escalating cost and prevalence of alternative medicine. Prev Med. 35(2):166–173. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1057. 2002 Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marstedt G, Moebus S. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Berlin, Germany: Robert Koch Institut; 2002. Inanspruchnahme alternativer Methoden in der Medizin; pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachinger E, Bauer R, Ritter H. Stadt Wien. 1997. Gesundheitsbericht für Wien 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachinger E, Bauer R, Ritter H. Stadt Wien. 1999. Gesundheitbericht für Wien 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanssen B, Grimsgaard S, Launsø L, Fønnebø V, Falkenberg T, Rasmussen NK. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in the Scandinavian countries. Scand J Prim Health Care. 23(1):57–62. doi: 10.1080/02813430510018419. 2005 Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crivelli L, Ferrari D, Limoni C. Inanspruchnahme von 5 Therapien der Komplementärmedizin in der Schweiz. Statistische Auswertung auf der Basis der Daten der Schweizerischen Gesundheitsbefragung 1997 und 2002. Manno, Switzerland: Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana; 2004. p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni H, Simile C, Hardy AM. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine by United States adults: results from the 1999 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 40(4):353–358. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204000-00011. 2002 Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. Prevalence and cost of alternative medicine in Australia. Lancet. 347(9001)(9001):569–573. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91271-4. 1996 Mar 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacLennan AH, Myers SP, Taylor AW. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: costs and beliefs in 2004. Med J Aust. 184(1):27–31. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00092.x. 2006 Jan 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menniti-Ippolito F, Gargiulo L, Bologna E, Forcella E, Raschetti R. Use of unconventional medicine in Italy: a nation-wide survey. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002 Apr;58(1):61–64. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0435-8. Epub 2002 Mar 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas KJ, Nicholl JP, Coleman P. Use and expenditure on complementary medicine in England: a population based survey. Complement Ther Med. 9(1):2–11. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0407. 2001 Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas K, Coleman P. Use of complementary or alternative medicine in a general population in Great Britain. Results from the National Omnibus survey. J Public Health (Oxf). 26(2):152–157. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh139. 2004 Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarland B, Bigelow D, Zani B, Newsom J, Kaplan M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in Canada and the United States. Am J Public Health. 92(10):1616–1618. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1616. 2002 Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ock SM, Choi JY, Cha YS, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in a general population in South Korea: results from a national survey in 2006. J Korean Med Sci. 2009 Feb;24(1):1–6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.1.1. Epub 2009 Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pirotta MV, Cohen MM, Kotsirilos V, Farish SJ. Complementary therapies: have they become accepted in general practice. Med J Aust. 172(3):105–109. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb127932.x. 2000 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyodo I, Eguchi K, Nishina T, et al. Perceptions and attitudes of clinical oncologists on complementary and alternative medicine: a nationwide survey in Japan. Cancer. 97(11):2861–2868. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11402. 2003 Jun 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baugniet J, Boon H, Ostbye T. Complementary/alternative medicine: comparing the view of medical students with students in other health care professions. Fam Med. 32(3):178–184. 2000 Mar. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozcakir A, Sadikoglu G, Bayram N, Mazicioglu MM, Bilgel N, Beyhan I. Turkish general practitioners and complementary/alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 13(9):1007–1010. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.7168. 2007 Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeKeyser FG, Bar Cohen B, Wagner N. Knowledge levels and attitudes of staff nurses in Israel towards complementary and alternative medicine. J Adv Nurs. 36(1):41–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01941.x. 2001 Oct. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW. Australian oncologists' self-reported knowledge and attitudes about non-traditional therapies used by cancer patients. Med J Aust. 172(3):110–113. 2000 Feb 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Münstedt K, von Georgi R. [Unconventional cancer therapies–comparisons of attitudes and knowledge between physicians in Germany and Greece] Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2005 Oct;12(5):254–260. doi: 10.1159/000088339. Epub 2005 Oct 13. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wahner-Roedler DL, Vincent A, Elkin PL, Loehrer LL, Cha SS, Bauer BA. Physicians' attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine and their knowledge of specific therapies: a survey at an academic medical center. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006 Dec;3(4):495–501. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel036. Epub 2006 Jun 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkin MR, Pearcy RM, Fraser JS. A comparison of the attitudes shown by general practitioners, hospital doctors and medical students towards alternative medicine. J R Soc Med. 87(9):523–525. 1994 Sep. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson MA, Mâsse LC, Nanny K, Sanders C. Discrepant views of oncologists and cancer patients on complementary/alternative medicine. Support Care Cancer. 12(11):797–804. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0677-3. 2004 Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf U, Maxion-Bergemann S, Bornhöft G, Matthiessen PF, Wolf M. Use of complementary medicine in Switzerland. Forsch Komplementmed. 2006;13((Suppl 2)):4–6. doi: 10.1159/000093488. Epub 2006 Jun 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodeker G, Ong CK, Grundy C, Burford G, Shein K. WHO Global Atlas of Traditional, Complementary, and Alternative Medicine. Kobe, Japan: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: implications for integrated care. Arch Intern Med. 162(15):1697–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1697. 2002 Aug 12-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bausell RB, Lee WL, Berman BM. Demographic and health-related correlates to visits to complementary and alternative medical providers. Med Care. 39(2):190–196. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200102000-00009. 2001 Feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kersnik J. Predictive characteristics of users of alternative medicine. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 130(11):390–394. 2000 Mar 18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palinkas LA, Kabongo ML ; San Diego Unified Practice Research in Family Medicine Network. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by primary care patients. A SURF*NET study. J Fam Pract. 49(12):1121–1130. 2000 Dec. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shmueli A, Shuval J. Are users of complementary and alternative medicine sicker than non-users. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007 Jun;4(2):251–255. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel076. Epub 2006 Oct 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unkelbach R, Abholz HH. [Differences between patients of conventional and anthroposophic family physicians] Forsch Komplementmed. 2006 Dec;13(6):349–355. doi: 10.1159/000096224. Epub 2006 Dec 21. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams J, Sibbritt DW, Easthope G, Young AF. The profile of women who consult alternative health practitioners in Australia. Med J Aust. 179(6):297–300. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05551.x. 2003 Sep 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millar WJ. Patterns of use—alternative health care practitioners. Health Rep. 13(1):9–21. 2001 Dec. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 279(19):1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. 1998 May 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. A systematic review of beliefs involved in the use of complementary and alternative medicine. J Health Psychol. 12(6):851–867. doi: 10.1177/1359105307082447. 2007 Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Honda K, Jacobson JS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among United States adults: the influences of personality, coping strategies, and social support. Prev Med. 40(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.001. 2005 Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huber R, Lüdtke R, Beiser I, Koch D. Coping strategies and the request for a consultation on complementary and alternative medicine—a cross-sectional survey of patients in a psychosomatic and three medical departments of a German university hospital. Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd. 11(4):207–211. doi: 10.1159/000080556. 2004 Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spadacio C, Barros NF. [Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients: systematic review] Rev Saude Publica. 2008 Feb;42(1):158–164. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102008000100023. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaye AD, Kaye AJ, Swinford J, et al. The effect of deep-tissue massage therapy on blood pressure and heart rate. J Altern Complement Med. 14(2):125–128. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0665. 2008 Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]