Abstract

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) have been implicated in a number of human diseases, including cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular disorders. Although for some of these conditions molecular mechanisms are now better understood, the big picture connecting distinct structural properties and functional repertoire of IDPs to pathogenesis and disease progression is still incomplete. Recent studies suggest that signaling and regulatory roles carried out by IDPs require them to be tightly regulated, and that altered IDP abundance may lead to disease. Here, we propose another link between IDPs and disease that takes into account disease-associated missense mutations located in the intrinsically disordered regions. We argue that such mutations are more prevalent and have larger functional impact than previously thought. In addition, we demonstrate that deleterious amino acid substitutions that cause disorder-to-order transitions are particularly enriched among disease mutations compared to neutral polymorphisms. Finally, we discuss potential differences in functional outcomes between disease mutations in ordered and disordered regions, and challenge the conventional structure-centric view of missense mutations.

Recent predictions suggest that more than 40% of human proteins have at least one long region ( ≥30 residues) that under physiological conditions does not fold into a fixed three-dimensional structure.1 These intrinsically unstructured or intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) mediate important biological functions such as post-translational modification, molecular recognition and assembly, as well as binding to other proteins, DNA and RNA.2–6 Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) frequently serve as hubs in protein–protein interaction networks,7 and their disordered regions allow binding to multiple partners.8,9 In comparison to ordered regions, IDRs generally have lower sequence conservation,10 with the exception of IDRs involved in RNA binding and chaperone activity.11 Disordered proteins were shown to be involved in a number of human diseases,12,13 and disruption of tight regulation of IDPs could be a contributor to disease pathogenesis.14 Given the high prevalence of disordered regions in the human proteome1,15,16 and their involvement in human diseases, below we explore whether disease-associated mutations could be found in IDRs and what is a possible impact of such mutations on protein disorder.

Historically, disease-associated mutations have been studied from a structural perspective,17–22 and much of the attention was focused on understanding how missense mutations influence folding, stability, solubility, activity and other structure-based properties of proteins. Significant progress has been made over the years in classifying potential functional effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), especially in the context of their influence on human health. This is illustrated by the development of numerous predictors of functional impact of SNPs (ref. 23–25 and others). However, the majority of these methods are structure-and/or conservation-based, which limits their applicability in protein regions with unknown structure or low sequence conservation. In addition, until recently only conserved regions of proteins were considered to be functionally important. As a consequence, existing methods often classify mutations within non-conserved regions as tolerant, not damaging or benign,26 because they are believed to be functionally neutral. For example, the SIFT algorithm tends to incorrectly classify the effect of mutations located in non-conserved,27 solvent accessible or disordered regions of proteins.26 Recent studies demonstrated that prediction accuracy, in particular within disordered regions, can be improved by incorporating prior functional information such as loss or gain of post-translational modification sites or catalytic residues.26,28 Here, we focus on missense mutations in IDRs and argue that mutations in generally non-conserved disordered regions can be highly deleterious because they can produce dramatic changes in disordered structure. Importantly, we propose that properties of mutations in disordered regions need to be taken into account when predicting the effects of missense mutations on protein structure and function. Below, we discuss the differences in the functional impact of mutations in ordered and disordered regions and relate them to different disease mechanisms.

We predicted disorder in the dataset of proteins that carry annotated disease mutations from the UniProt database29 using three different disorder predictors30–32 and observed that 20–25% of disease mutations were mapped to predicted disordered regions (Vacic and Iakoucheva, submitted). We believe that this number may be an underestimate because at least some of the mutations in UniProt are annotated as being disease-related because they disrupt important functional sites inferred from known structures. Then, we in silico mutated the wild type protein sequences to mimic the annotated disease mutations. We observed that 20% of disease mutations located in disordered regions cause disorder-to-order (D → O) transitions, defined here and throughout this manuscript as a change from predicted disorder (score ≥0.5) into order (score <0.5).30 In the two control data-sets, annotated polymorphisms from UniProt and neutral evolutionary substitutions, percentages of mutations that cause D → O transitions were significantly lower (11.5% and 7.3%, Fisher’s exact P = 1.06 × 10−32 and 5.47 × 10−105, respectively). Table 1 shows representative examples of D → O mutations that affect experimentally confirmed disordered regions of proteins from the DisProt database.33 In total, we have collected over 700 annotated disease mutations from UniProt that cause D → O transitions based on the disorder prediction score. As evident from these examples, disease mutations can also affect disordered regions, and some of them can disrupt disordered conformation via D → O transitions.

Table 1.

Examples of disease mutations located in the experimentally confirmed disordered regions from DisProt proteins

| Protein ID | Protein name | Mutation position | Wild type residue | Mutant residue | PONDR disorder score

|

Disease | DisProt ID | Disordered region(s) position and function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | Δ | ||||||||

| MECP2 | Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 | 306 | R | C | 0.96 | 0.37 | 0.59 | Rett syndrome (RTT) [MIM:312750] | DP00539 | #207–310; #335–486: Molecular recognition effectors, Intraprotein interaction, Protein–DNA binding, Protein–protein binding |

| R | H | 0.96 | 0.47 | 0.49 | Rett syndrome (RTT) [MIM:312750] | |||||

| 453 | R | Q | 0.86 | 0.4 | 0.46 | Mental retardation syndromic X-linked type 13 [MIM:300055] | ||||

| BRCA1 | Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein | 227 | E | K | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.41 | Ovarian cancer [MIM:113705] | DP00238 | #170–1649:Molecular recognition effectors, Protein–protein binding |

| 835 | H | Y | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0.40 | Familial breast-ovarian cancer type 1 [MIM:604370] | ||||

| 1204 | R | I | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.19 | Breast cancer [MIM:113705, 114480] | ||||

| 1217 | S | Y | 0.83 | 0.4 | 0.43 | Breast cancer [MIM:113705, 114480]; Familial breast-ovarian cancer type 1 [MIM:604370] | ||||

| TP53 | Tumor suppressor p53 | 17 | E | D | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.20 | Sporadic cancers | DP00086 | #1–73:Molecular recognition effectors |

| 34 | P | L | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.14 | Sporadic cancers | ||||

| 35 | L | F | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.16 | Sporadic cancers | ||||

| 46 | S | F | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.29 | Sporadic cancers | ||||

| 47 | P | L | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.27 | Sporadic cancers | ||||

| 49 | D | Y | 0.79 | 0.34 | 0.45 | Sporadic cancers | ||||

| VHL | von Hippel-Lindau Tumor Suppressor | 65 | S | W | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.12 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300] | DP00287 | #1–213 |

| S | L | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.05 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300] | |||||

| 66 | V | F | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0.17 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300] | ||||

| 167 | R | G | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.24 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300] | ||||

| R | W | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.40 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300]; | |||||

| R | Q | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.24 | Pheochromocytoma [MIM:171300] | |||||

| 176 | R | W | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.38 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300] | ||||

| 200 | R | W | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.23 | Von Hippel-Lindau disease [MIM:193300]; Erythrocytosis familial type 2 [MIM:263400] | ||||

| NR3C1 | Glucocorticoid receptor | 477 | R | H | 0.75 | 0.4 | 0.35 | Glucocorticoid resistance [MIM:138040] | DP00030 | #1–500:Molecular recognition effector, Metal binding, Phosphorylation, Protein–protein binding, Protein–DNA binding |

| TNNI3 | Troponin I, cardiac muscle | 166 | S | F | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.2 | Cardiomyopathy familial hypertrophic type 7 [MIM:191044] | DP00166 | #163–210:Molecular recognition effector, Molecular assembly, Entropic chain, Flexible linkers/spacers, Protein–protein binding |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase | 125 | D | G | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.07 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 1 [MIM:105400] | DP00652 | #67–79; #125–141: Metal binding |

| D | V | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.11 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 1 [MIM:105400] | |||||

| 126 | D | H | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.15 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 1 [MIM:105400] | ||||

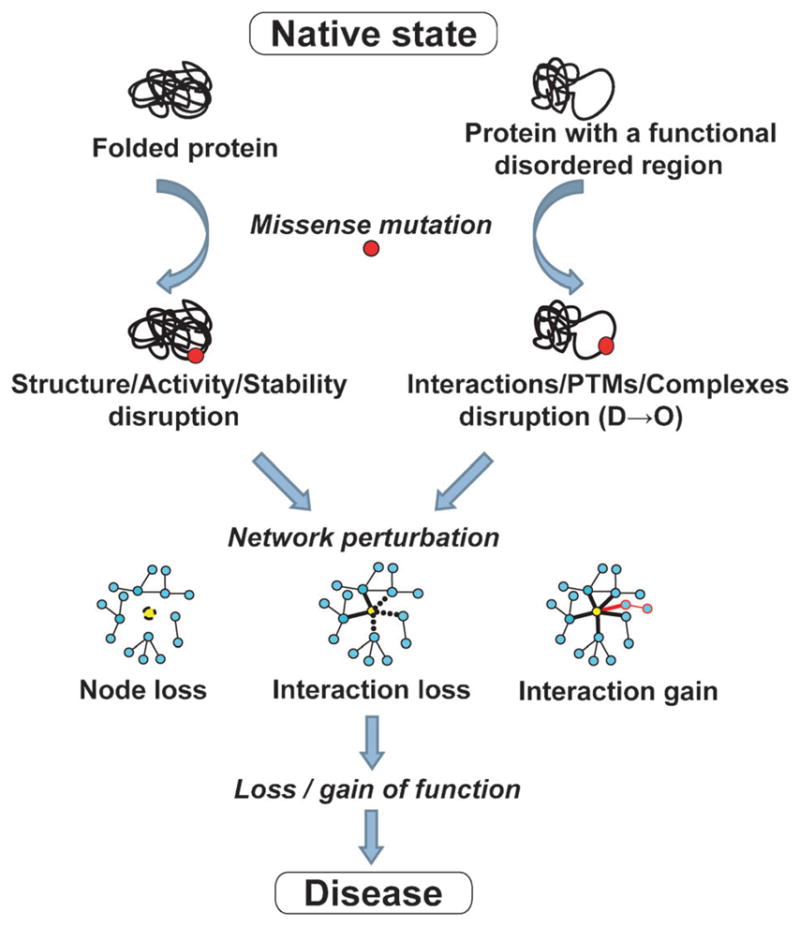

Ordered and disordered proteins have distinct functional repertoires: while ordered proteins are mainly involved in metabolism, biosynthesis, catalysis and related cellular processes, disordered proteins carry out regulatory and signaling roles.4,5,34 Disordered regions are believed to be involved in low affinity and high specificity binding of IDPs to their targets.35,36 It is therefore likely that the functional impact of disease mutations in these two types of regions would also differ. A plausible hypothesis for the impact of disease mutations in disordered regions is that they primarily disrupt disorder-mediated processes such as protein–protein, protein–DNA, protein–RNA and protein–ligand interactions, post-translational modifications, assembly of macromolecular complexes, and thereby signaling and regulatory networks (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the potential impact of disease mutations in ordered and disordered regions.

According to the traditional structure-centric view of disease mutations, a disease may arise from malfunction of a specific protein due to the loss of its stably folded structure or enzymatic activity (Fig. 1). Examples of such disease mechanisms are plentiful in the literature. For instance, in the case of phenylketonuria (OMIM #261600) most of the associated missense mutations impair enzymatic activity of the phenylalanine hydroxylase protein (PHA) by causing its increased instability and aggregation. Furthermore, it was shown that the decrease in PHA stability is the main molecular pathogenic mechanism in phenylketonuria and the determinant of phenotypic outcome in the patients.37 Another example of a metabolic disorder characterized by enzymatic deficiency is homo-cystinuria (OMIM #236200), which is usually caused by the mutations in the gene that encodes cystathionine beta-synthase.

On the other hand, a new disorder-centric view of missense mutations suggests that a disease may arise from a loss (of wanted) or gain (of unwanted) interactions between a candidate protein and its interaction partners due to mutations that disrupt disordered regions (Fig. 1). Although these two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive—loss of enzyme’s activity could in addition eliminate some of its interactions with the corresponding ligands/partners—disruption of signaling and regulatory networks via interaction-specific defects is the most plausible mechanism for diseases that involve mutations in IDRs. This hypothesis agrees with the study by Zhong et al.,38 who investigated how disease mutations affect the human protein–protein interaction network. Using a small set of carefully chosen missense mutations, they were able to demonstrate that perturbations of the interactome can be caused by either a complete loss of gene products (node removal), or by interaction-specific (edgetic) alterations. Mutations leading to node removal were likely to affect buried residues of the protein (comparable to ordered regions), whereas mutations leading to loss or gain of specific interactions were likely to lie on the protein surface38 (comparable to disordered regions). Although both of these mechanisms influence interaction networks, they could have different consequences, especially with regard to disease mechanisms and modes of disease inheritance.38

Role of IDPs as network hubs7,8 could further contribute to the network disruption in disease. The ‘edgetic’ network perturbations that disrupt interactions of hub proteins may result in an imbalanced amount of protein complex subunits. Defective protein complexes may not function properly in the cell, or may be rapidly degraded by the cellular proteolytic machinery. The loss of post-translational modifications (PTMs) could be another potential outcome of the ‘edgetic’ networks perturbation. Our group and others have previously shown that disorder is required for post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation,2 ubiquitination,3 methylation39 and possibly other PTMs. D → O transition mutations could render modification sites less exposed and thus impair the access of modifying enzymes to the PTM sites. As a result, the loss of ubiquitination sites could lead to accumulation of dosage-sensitive IDPs40 inside the cell, thereby contributing to disease development. Likewise, access of kinases to phosphorylation sites may be compromised by D → O mutations of the site or its flanking regions, which could influence downstream signaling cascades. D → O mutations could also alter the binding specificity or affinity of IDPs to their partners, thereby leading to either more promiscuous binding or to accumulation of highly stable complexes. Both of these outcomes are undesirable for the finely tuned and dynamic signaling networks, where interactions need to be precise and at the same time easily breakable. This is especially relevant for the fuzzy complexes that rely on dynamic disorder,41 since dynamically disordered regions could be especially prone to disruption by D → O mutations. In addition, D → O transition mutations could impair regulatory functions of IDPs. As shown previously, IDPs are enriched among transcription and translation regulators, nucleotide-binding proteins and proteins involved in signal transduction.12,15,34 By affecting DNA-binding properties of these IDPs, D → O mutations could disrupt transcriptional regulatory networks that control global gene expression. All of these and other ways of network disruptions via D →O mutations in IDPs could trigger disease development.

Another important observation that followed from our analysis of the disease-associated mutations in UniProt is the increased frequency of several specific mutations. When disease mutations were ranked according to their frequency of occurrence in the UniProt database, top five disorder-to-order transition mutations (R → W, R → C, E → K, R → H and R → Q) collectively accounted for 44.0% of all D → O disease mutations (Table 2). Similarly, top five order-to-disorder (O → D) transition mutations (L → P, C → R, G → R, W → R and G → E) collectively accounted for 32.2% of all O → D disease mutations (Table 2). This demonstrates that a limited set of the specific “transition” mutations accounts for a large fraction of D → O and O → D disease mutations. We believe that this observation is important to consider while developing the classifiers of the functional impact of mutations on protein structure and function, and knowing the preferential “from-to” residue transition could help to better predict which newly discovered mutation is likely to be deleterious. Below, we discuss one example from Table 1, Methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), with three D → O transition mutations that are mapped to its annotated disordered regions from DisProt.

Table 2.

Frequencies of the top five D → O and O → D disease mutations from the UniProt database

| Substitution | D → O disease mutations (%) | Substitution | O → D disease mutations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R → W | 13.1 | L → P | 11.9 |

| R → C | 10.3 | C → R | 6.6 |

| R → H | 7.6 | G → R | 6.1 |

| E → K | 6.7 | W → R | 4.1 |

| R → Q | 6.3 | F → S | 3.6 |

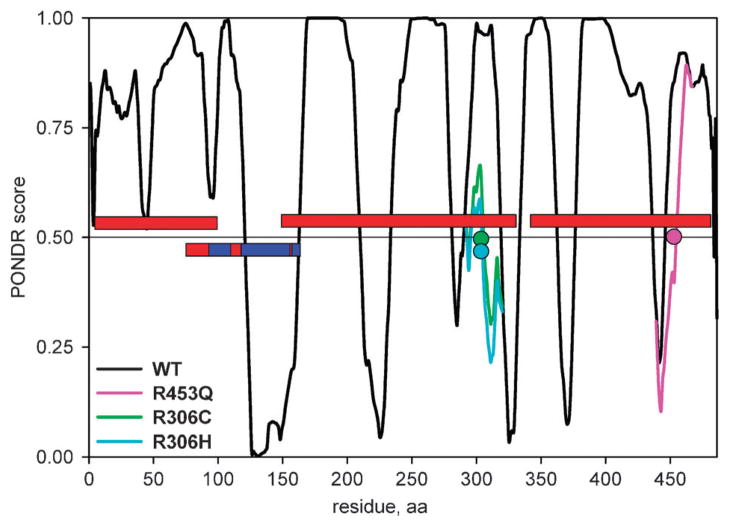

MeCP2 is a methylated DNA-binding protein that mediates transcriptional repression via interaction with the histone deacetylase and is essential for embryonic development. MeCP2 carries a number of missense, nonsense, frame shift and copy number mutations which are associated with various neurodevelopmental disorders such as Rett syndrome, autism spectrum disorders and mental retardation.42–44 The structure and disorder of MeCP2 have been extensively investigated. About 60% of its sequence is intrinsically unstructured, as determined by various experimental methods (CD, NMR, analytical ultracentrifugation and far-UV CD spectroscopy)45,46 (Fig. 2). The NMR and X-ray crystal structure of the methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) of MeCP2 has been solved,47,48 and the coordinates of the termini of this domain and several internal residues within MBD could not be assigned, which indicates some amount of disorder even within this structured domain. There are three D → O transition mutations in UniProt that map to the disordered regions of MeCP2 annotated in the DisProt database, R306C, R306H and R453Q (Table 1, Fig. 2). When introduced into the wild type MeCP2 sequence in silico, both R306C and R306H mutations result in a dramatic drop of the disorder score in the 207–310 disordered region, which corresponds to a transcriptional repressor domain (TRD) of MeCP249 (Fig. 2). The R453Q mutation causes a drop and a shift in the position of the disordered region 335–486, or C-terminal (CTD-β) domain46 (Fig. 2). Both of these domains have been shown to be important for binding to unmethylated DNA, and the synergistic binding to DNA was observed for the TRD-CTD construct, which binds to DNA with 6-fold higher affinity than TRD and 30-fold higher affinity than CTD alone.46 Furthermore, is has been demonstrated that CTD-β domain binds to nucleosomes,46 most likely to histone H3.50 Given the important functional roles of these two domains, the D → O transition mutations could lead to partial or complete impairment of their DNA- and nucleosome-binding properties. Confidently establishing links between specific D → O (and O → D) transition mutations and disruption of domain or protein function using experimental methods is an important step for better understanding the disease mechanisms.

Fig. 2.

PONDR VLXT disorder predictions for the wild-type MECP2 and its three D → O mutants that overlap with the experimentally confirmed MECP2 disordered regions from DisProt. The red bars denote the location of the disordered regions, the red/blue bar denotes the MECP2 region for which the structure was determined (red regions within the blue bar indicate approximate location of the disordered regions in the structure), the colored circles denote the location of mutations, the colored lines denote new disorder predictions after introducing mutation into the wild type sequence in silico.

Knowing the functional impact of disease mutations in disordered regions has another interesting implication. Recent literature suggests that disordered regions could serve as drug targets for small molecules and short peptides.51,52 The potential to target disordered regions carrying disease mutations opens a broad range of possibilities in terms of prioritizing the regions with the most deleterious mutations as drug targets; directing the binding of small molecules towards specific D → O mutations; or even attempting to compensate for the interactions that may be disrupted by such D →O mutations. Since the area of drug development targeting disordered regions, and especially D → O mutations within them, is still largely unexplored, there are many opportunities for future research in this respect.

It is an extremely exciting time for discovery of mutations associated with human diseases. Recent advances in next-generation DNA sequencing technologies53 are bringing a complete catalog of individual genetic variation within reach,54 and the decrease in sequencing cost is allowing studies of ever larger disease cohorts.55 As the list of mutations associated with human diseases grows, it is likely that some of them will be mapped to protein-coding regions, and a subset of them specifically to disordered regions. However, interpreting disease risk associated with the identified genetic variants still remains a formidable challenge. Thus, further development of methods to predict functional impact of newly discovered SNPs, especially in disordered regions, is critically needed. This is all the more warranted by the fact that disordered regions have fewer evolutionary constraints compared to ordered regions,56 but nevertheless they could carry deleterious mutations, as demonstrated above. We propose that more specialized predictors trained using properties and features of mutations in ordered and disordered regions would be better suited for this purpose than the “one-size-fits-all” models. They are likely to outperform the methods developed to target both ordered and disordered regions without discrimination, because the spectrum of mutations and their functional consequences differ dramatically between these two types of structures. The available domain–domain, protein–protein, and possibly even network-level interaction information should ideally be accounted for while developing such predictors. The first step in this direction has recently been made by incorporating some of the unstructured regions’ properties as training features of the predictor.26

We believe that it is very important that the structure-centric view of mutations changes to account for disease mutations in disordered regions. Although the focus of this opinion was on missense mutations, it is also necessary to recognize that the entire gamut of disease-related mutations including splice-site mutations, indels, nonsense mutations, and copy number variation could impact disordered regions of proteins in a similar way as they are impacting ordered regions, however with likely varying outcomes. There is still much awaiting to be explored in the area of disease mutations and protein disorder. More rigorous computational and experimental studies integrating genomic, biophysical and biochemical data would contribute to a better understanding of the role of mutations in disordered regions and their relevance to human diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in whole or in part with the following grants: NSF MCB0444818 (LMI), NIH RO1 HD065288 (LMI), NIH RO1 MH091350 (LMI). We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their help in improving the manuscript. Molecular Kinetics Inc is acknowledged for allowing us to use PONDR VLXT predictor.

Footnotes

Published as part of a Molecular BioSystems themed issue on Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Guest Editor M. Madan Babu.

References

- 1.Pentony MM, Ward J, Jones DT. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;604:369–393. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-444-9_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iakoucheva LM, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, O’Connor TR, Sikes JG, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1037–1049. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radivojac P, Vacic V, Haynes C, Cocklin RR, Mohan A, Heyen JW, Goebl MG, Iakoucheva LM. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2010;78:365–580. doi: 10.1002/prot.22555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6573–6582. doi: 10.1021/bi012159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tompa P. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002:27. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. FEBS J. 2005;272:5129–5148. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynes C, Oldfield CJ, Ji F, Klitgord N, Cusick ME, Radivojac P, Uversky VN, Vidal M, Iakoucheva LM. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekman D, Light S, Bjorklund AK, Elofsson A. GenomeBiology. 2006;7:R45. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-6-r45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CJ, Johnson AK, Dunker AK, Daughdrill GW. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellay J, Han S, Michaut M, Kim T, Costanzo M, Andrews BJ, Boone C, Bader GD, Myers CL, Kim PM. GenomeBiology. 2011;12:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iakoucheva LM, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:573–584. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babu MM, van der Lee R, de Groot NS, Gsponer J. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, McGuffin LJ, Buxton BF, Jones DT. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunker AK, Obradovic Z, Romero P, Garner EC, Brown CJ. Genome Informat. 2000;11:161–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steward RE, MacArthur MW, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. Trends Genet. 2003;19:505–513. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebbeck TR, Spitz M, Wu X. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:589–597. doi: 10.1038/nrg1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Moult J. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:263–270. doi: 10.1002/humu.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chasman D, Adams RM. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:683–706. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer-Costa C, Orozco M, de la Cruz X. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:771–786. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders CT, Baker D. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:891–901. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00813-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Bork P. Trends Genet. 2000;16:198–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)01988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yue P, Melamud E, Moult J. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mort M, Evani US, Krishnan VG, Kamati KK, Baenziger PH, Bagchi A, Peters BJ, Sathyesh R, Li B, Sun Y, Xue B, Shah NH, Kann MG, Cooper DN, Radivojac P, Mooney SD. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:335–346. doi: 10.1002/humu.21192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, Iakoucheva LM, Mooney SD, Radivojac P. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2010:337–347. doi: 10.1142/9789814295291_0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yip YL, Famiglietti M, Gos A, Duek PD, David FP, Gateau A, Bairoch A. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:361–366. doi: 10.1002/humu.20671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero P, Obradovic Z, Li X, Garner EC, Brown CJ, Dunker AK. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 2001;42:38–48. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010101)42:1<38::aid-prot50>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obradovic Z, Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Dunker AK. Proteins. 2005 doi: 10.1002/prot.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. Bioinformatics. 2005 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sickmeier M, Hamilton JA, LeGall T, Vacic V, Cortese MS, Tantos A, Szabo B, Tompa P, Chen J, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D786–793. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie H, Vucetic S, Iakoucheva LM, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1882–1898. doi: 10.1021/pr060392u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csermely P, Palotai R, Nussinov R. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pey AL, Stricher F, Serrano L, Martinez A. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1006–1024. doi: 10.1086/521879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong Q, Simonis N, Li QR, Charloteaux B, Heuze F, Klitgord N, Tam S, Yu H, Venkatesan K, Mou D, Swearingen V, Yildirim MA, Yan H, Dricot A, Szeto D, Lin C, Hao T, Fan C, Milstein S, Dupuy D, Brasseur R, Hill DE, Cusick ME, Vidal M. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:321. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daily KM, Radivojac P, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder and protein modifications: building an SVM predictor for methylation. IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (CIBCB); San Diego, CA. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gsponer J, Futschik ME, Teichmann SA, Babu MM. Science. 2008;322:1365–1368. doi: 10.1126/science.1163581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tompa P, Fuxreiter M. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Nat Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramocki MB, Peters SU, Tavyev YJ, Zhang F, Carvalho CM, Schaaf CP, Richman R, Fang P, Glaze DG, Lupski JR, Zoghbi HY. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:771–782. doi: 10.1002/ana.21715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lam CW, Yeung WL, Ko CH, Poon PM, Tong SF, Chan KY, Lo IF, Chan LY, Hui J, Wong V, Pang CP, Lo YM, Fok TF. J Med Genet. 2000;37:E41. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.12.e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams VH, McBryant SJ, Wade PA, Woodcock CL, Hansen JC. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15057–15064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghosh RP, Nikitina T, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Gierasch LM, Uversky VN, Hite K, Hansen JC, Woodcock CL. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4395–4410. doi: 10.1021/bi9019753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wakefield RI, Smith BO, Nan X, Free A, Soteriou A, Uhrin D, Bird AP, Barlow PN. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:1055–1065. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho KL, McNae IW, Schmiedeberg L, Klose RJ, Bird AP, Walkinshaw MD. Mol Cell. 2008;29:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nan X, Campoy FJ, Bird A. Cell. 1997;88:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nikitina T, Shi X, Ghosh RP, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Hansen JC, Woodcock CL. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:864–877. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01593-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Metallo SJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shendure J, Ji H. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Thousand Genomes Project Consortium. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cooper GM, Shendure J. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:628–640. doi: 10.1038/nrg3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown CJ, Johnson AK, Daughdrill GW. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:609–621. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]