Abstract

N-type calcium (Ca2+) channels play a critical role in synaptic function, but the mechanisms responsible for their targeting in neurons are poorly understood. N-type channels are formed by an α1B (CaV2.2) pore-forming subunit associated with β and α2δ auxiliary subunits. By expressing epitope-tagged recombinant α1B subunits in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures, we demonstrate here that synaptic targeting of N-type channels depends on neuronal contacts and synapse formation. We also establish that the C-terminal 163 aa (2177–2339) of the α1B-1 (CaV2.2a) splice variant contain sequences that are both necessary and sufficient for synaptic targeting. By site-directed mutagenesis, we demonstrate that postsynaptic density-95/discs large/zona occludens-1 and Src homology 3 domain-binding motifs located within this region of the α1B subunit (Maximov et al., 1999) act as synergistic synaptic targeting signals. We also show that the recombinant modular adaptor proteins Mint1 and CASK colocalize with N-type channels in synapses. We found that the α1B-2(CaV2.2b) splice variant is restricted to soma and dendrites and postulated that somatodendritic and axonal/presynaptic isoforms of N-type channels are generated via alternative splicing of α1B C termini. These data lead us to propose that during synaptogenesis, the α1B-1 (CaV2.2a) splice variant of the N-type Ca2+ channel pore-forming subunit is recruited to presynaptic locations by means of interactions with modular adaptor proteins Mint1 and CASK. Our results provide a novel insight into the molecular mechanisms responsible for targeting of Ca2+ channels and other synaptic proteins in neurons.

Keywords: calcium channels, polarized cells, PDZ domains, protein targeting, axons, synapse

Neurons are highly polarized cells: the structural, functional, and molecular differences between their axonal and somatodendritic domains underlie their ability to receive, process, and transmit information. The unique complement of ion channels, receptors, and cytoplasmic and cytoskeleton proteins is present in neuronal somatodendritic and axonal compartments (Craig and Banker, 1994). Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in targeting of neuronal proteins have been elucidated recently (Higgins et al., 1997; Winckler and Mellman, 1999). Primary cultures of rat hippocampal neurons are the most widely used model for these studies. Axons and dendrites of hippocampal neurons display distinctive and characteristic morphologies; axons are consistently presynaptic, and dendrites are consistently postsynaptic (Craig and Banker, 1994). Correct localization of synaptic constituents in hippocampal neurons has been proposed to result from a two-step process: initial targeting to axonal or somatodendritic domains based on intrinsic sorting signals, followed by clustering at presynaptic and postsynaptic sites that depends on cell-to-cell contacts (Craig and Banker, 1994).

Presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediate rapid Ca2+ influx into the synaptic terminal that triggers synaptic vesicle exocytosis and neurotransmitter release (Llinas et al., 1981). Multiple types of Ca2+ channels (N-type, P/Q-type, L-type, R-type, and T-type) are expressed in neurons (Tsien et al., 1991). N-type Ca2+ channels [encoded by the α1B (CaV2.2) pore-forming subunit] (Williams et al., 1992; Ertel et al., 2000) and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels [encoded by the α1A (CaV2.1) pore-forming subunit] (Mori et al., 1991; Ertel et al., 2000) play a predominant role in supporting chemical neurotransmission in central synapses (Takahashi and Momiyama, 1993; Wheeler et al., 1994; Dunlap et al., 1995; Reuter, 1995). How are N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels targeted to synaptic locations? It has been demonstrated that neuron-to-neuron contact is required for N-type Ca2+ channel clustering during synapse formation in rat hippocampal neuronal culture (Bahls et al., 1998). More recently, synaptic targeting of an auxiliary P/Q-type Ca2+ channel subunit β4 was investigated (Wittemann et al., 2000). However, a number of fundamental questions regarding synaptic Ca2+ channel targeting to the synapse remain unanswered.

Here we investigated targeting of recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels to synaptic locations in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures. We found that in immature and in mature low-density hippocampal cultures, recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels were uniformly distributed in both axonal and somatodendritic compartments. In contrast, in mature high-density cultures, the recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels were clustered in presynaptic sites and primarily excluded from the somatodendritic domain. Synaptic clustering of recombinant N-type channels depended critically on the most C-terminal region of the “long” splice variant of the N-type Ca2+ channel pore-forming subunit α1B-1(CaV2.2a) (Williams et al., 1992; Ertel et al., 2000). In a previous paper, we identified postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95)/discs large/zona occludens-1 (PDZ) and Src homology 3 (SH3) domain-binding motifs in the same region of the α1B subunit (Maximov et al., 1999). Here we show that these motifs act as synergistic synaptic targeting signals for N-type channels in rat hippocampal neurons. Our results provide a novel insight into the molecular mechanisms responsible for targeting of Ca2+ channels and other synaptic proteins in neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression constructs. The human α1B (Ellinor et al., 1994), rabbit α2/δ-1 (Mikami et al., 1989), and rabbit β3 (Hullin et al., 1992) coding sequences were subcloned into mammalian expression vectors [pCMV-HA (a gift from Thomas Südhof, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) or pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA)]. The following expression constructs were generated: hemagglutinin (HA)-α1B = 1–2339 [the HA tag is connected to the α1B sequence via GIPQRNPEPLALCR linker; the first 72 aa in the α1B sequence are replaced by the homologous sequence from α1A as explained by Ellinor et al. (1994)], α1B-II/III-HA = 1–2339 (the HA tag was introduced between positions G844 and V845of the α1B sequence), HA-α1B-T2038X = 1–2038, HA-α1B-S2176X = 1–2176, HA-α1B-D2334X = 1–2333, HA-α1B-PXXP-A = 1–2339 [(2191PQTPLTPRP2199-(A)9], HA-α1B-PXXP-A/D2334X = 1–2333 [2191PQTPLTPRP2199-(A)9], and HA-NC3 = 2021–2339. The HA-α1B-rat NC2 splice variant (rNC2) construct was generated by replacing 2164–2339 aa of human HA-α1B construct with 2159–2299 aa of cloned rat NC2 splice variant (see below). All α1BC-terminal mutant and chimeric constructs were generated by cassette mutagenesis of human α1B coding sequence between XhoI (5304) and XbaI sites (3′ untranslated region). Wild-type coding sequence was replaced by mutated cassettes generated by standard or megaprimer PCR and subcloned into XhoI/XbaI sites. The locus of mutations was verified by sequencing. CD4-NC targeting constructs were generated on the basis of pMACS4.1 (CD4) plasmid (Miltenyi Biotech, Sunnyvale, CA): CD4-NC = 1743–2339 (1773–2275 and deletion 2306–2334), CD4-NC-D2334X = 2202–2333; CD4-QC = 2376–2505 of human α1A (Zhuchenko et al., 1997), and CD4-QC-D2501X = 2376–2501 of human α1A. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion constructs were generated on the basis of pEGFPC3 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) vector: GFP-NC3 = 2021–2339, GFP-Mint1 = 1–839 of rat Mint1 (Okamoto and Sudhof, 1997), GFP-CASK = 1–909 of rat CASK (Hata et al., 1996). Before neuronal transfections, the generated HA-α1B and CD4 expression constructs were expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) or COS7 cells and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA (HA-α1B) and anti-CD4 (CD4-NC) antibodies. All constructs were expressed in COS7 and HEK293 cells at similar levels, and their apparent molecular weights on the Western blot were in agreement with their predicted molecular weights (data not shown). In addition, we tested whether the wild-type and mutated HA-α1B targeting constructs support functional Ca2+ currents when expressed inXenopus oocytes, as described previously (Bezprozvanny et al., 1995). The size of the peak current and the inactivation properties of the expressed wild-type and mutant channels measured 3 d after cRNA injection (quantified as ratio of the peak current to the current at the end of the 50 msec pulse test pulse from −100 mV to 0 mV) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Functional properties of channels supported by the wild-type and mutant HA-α1B/α2δ/β3 subunit combinations expressed in Xenopus oocytes

| HA-α1B | Peak current (μA) | Peak current/end of 50 msec pulse |

|---|---|---|

| HA-α1B-WT | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.49 |

| HA-α1B-D2334X | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 2.0 ± 0.18 |

| HA-α1B-S2176X | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 2.8 ± 0.67 |

| HA-α1B-PXXP-A/D2334X | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 3.0 ± 0.66 |

| HA-α1B-rNC2 | 0.67 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.34 |

n ≥ 5 for each group. WT, Wild type.

Hippocampal neuronal cultures and neuronal transfection.Hippocampi were isolated from embryonic day 18 rat embryos and dissociated by digestion with trypsin (Invitrogen) and DNase I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (Goslin et al., 1998). Neurons were plated on glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma) and cultured on glial cell monolayer in MEM (phenol red-free) supplemented with glucose, B-27 (Invitrogen), and sodium pyruvate. The neurons were plated at high (60–80 neurons/mm2) or low (5–10 neurons/mm2) density as indicated in Results. Glial cell growth was inhibited by 4 μm AraC (Sigma). For transfection, conditioned medium was removed from cultures, and neurons were washed once in MEM and incubated for 30 min with the calcium-phosphate-DNA precipitates formed in HEPES-buffered saline (Crawley et al., 1997). Cells were then returned into conditioned medium and analyzed 2–4 d after transfection. A mixture of HA-α1B/α2δ/β3plasmids (molar ratio 3:1:1) was used to express N-type Ca2+ channels. The β3 subunit expressed as an HA- or GFP-fusion protein was uniformly distributed in neurons cultured in vitro for 7–14 d (data not shown), which rules out the possibility that β3 acts as an N-type Ca2+ channel targeting subunit.

Antibodies. The following monoclonal antibodies were used (listed by antibody and working concentration): MAP2 (Sigma) 1:1000; synaptotagmin I (STI) (Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) 1:50; CD4 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) 1:1000; CD4-FITC (Zymed) 1:100; HA.11 (Covance, Richmond, CA) 1:500; and synapsin I (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) 1:1000. Polyclonal MAP2 antibodies (Chemicon) were used at concentration of 1:500. When compared with monoclonal MAP2 antibodies, labeling with polyclonal MAP2 antibodies resulted in a more discrete pattern of distribution of marker in dendrites. In additional control experiments, we confirmed that the discrete staining pattern observed with polyclonal MAP2 antibodies does not result from fragmentation of neuronal processes. Polyclonal pan-synapsin and PSD-95 antibodies were kindly provided by Dr. Thomas Südhof and used at 1:1000. rNN antibodies have been described previously (Maximov et al., 1999). N-type splice-variant-specific C-terminal antibodies (NC1) were generated against a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein encoding C-terminal amino acids 2166–2333 of rat α1B. Antibodies were purified by affinity chromatography and used at 1:200 for immunoblotting and at 1:50 for immunoprecipitation.

Immunocytochemistry. Neurons were washed once in PBS, fixed for 10–15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose in PBS on ice, and permeabilized for 5 min at room temperature in 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS. For labeling with STI antibodies, life neurons were washed once in PBS and incubated in modified tiroid solution containing (in mm): 90 NaCl, 45 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, pH 7.2, and STI antibodies for 3 min. Cells were then washed three times in PBS, fixed, and permeabilized. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation of cells for 30 min in 5% BSA (fraction V; Sigma). Neurons were covered by primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution followed by incubation with the corresponding rhodamine- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Slides were washed with PBS and mounted in Moweol-488 (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA). For the experiment shown on Figure5H, life neurons were preincubated with 5 μm ω-GVIA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or ω-MVIIC (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL) for 30 min before STI labeling. Images were collected with a Zeiss(Thornwood, NY) microscope with 40× and 63× objectives. Digital images were captured with a cooled CCD camera (PhotoMetrics, Huntington Beach CA) and Oncor (Gaithersburg, MD) Image software and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and Scion (Frederick, MD) Image software. The fluorescence intensity profiles shown for Figures 2, 3, and 6 were created by manual tracing of selected areas of axons. The confocal images shown for Figures 1D,2G, and 4C were collected with a confocal Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope and 63× objective. Neuronal cell bodies were scanned starting from the surface of the cell with a 0.2-μm-thickness parameter. Confocal images were collected in Z-stacks using laser-scanning microscope software (Zeiss).

Fig. 5.

Dominant-negative effect of α1BC-terminal fragment on synaptic function. A, The experimental protocol for live labeling of active synapses with synaptotagmin luminal antibodies (STI) was adapted from Matteoli et al. (1992). The hippocampal neuronal cultures were preincubated with STI antibodies for 3 min in the presence of 45 mm KCl and 2 mm Ca2+. After stimulation, STI antibodies were washed out, and neurons were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody to visualize STI antibody localization. The intraluminal epitope of synaptotagmin is shown as a black box. B, Live labeling for STI (red) followed by fixation and labeling for MAP2 (green). Note that all STI-positive clusters are apposed to cell body and dendrites (MAP2-positive). Scale bar, 20 μm. C, Live staining for STI (left panel, red in merged image) followed by fixation and staining for synapsin (center panel, green on merged image) shows colocalization of STI clusters with presynaptic sites. On average, 93% of STI and synapsin clusters were colocalized (n = 200). Scale bar, 10 μm. D, Live staining for STI (red) of GFP-NC3 (green)-transfected neurons followed by fixation and staining for MAP2 (blue). Axons of transfected cells (green, MAP2-negative) are indicated bylarge arrows. The boxed portion of the image is enlarged in the D′ inset. Note that the intensity of individual STI clusters associated with axons of transfected neurons is reduced when compared with control clusters formed by GFP-NC3-negative axons. Small arrows inD′ indicate synapses of transfected cells. Scale bars:D, 20 μm; D′, 10 μm.E, Live staining for STI (red) of neurons expressing mGFP (green). Note that the intensity of individual STI clusters associated with axons of mGFP-transfected neurons is not affected. Small arrows in Eindicate synapses of transfected cells. Scale bar, 10 μm.F, Quantitative analysis of the intensity of individual clusters of STI (left panel), synapsin (center panel), and PSD-95 (right panel) associated with control (nontransfected) cells and cells transfected with mGFP or GFP-NC3 as indicated. For each transfection, the fluorescence intensity of individual STI, synapsin, and PSD-95 clusters was normalized to the average fluorescence intensity of corresponding clusters observed for control (nontransfected) cells in the same field. The normalized intensities are shown as mean ± SEM (n = number of clusters analyzed). For STI plot: control, n = 309; mGFP, n = 55; GFP-NC3, n = 90 (*p < 0.001 when GFP-NC3 is compared with control and mGFP). For synapsin and PSD-95, n ≥ 75 for controls and n ≥ 25 for mGFP and GFP-NC3.G, Cumulative distribution of intensities of individual STI clusters associated with axons of nontransfected neurons (control, ■) or axons of neurons expressing mGFP (○) and GFP-NC3 (●).H, Effect of GFP-NC3 expression on STI uptake by neurons preincubated with 5 μm ω-GVIA or 5 μmω-MVIIC (n ≥ 25 for each group).

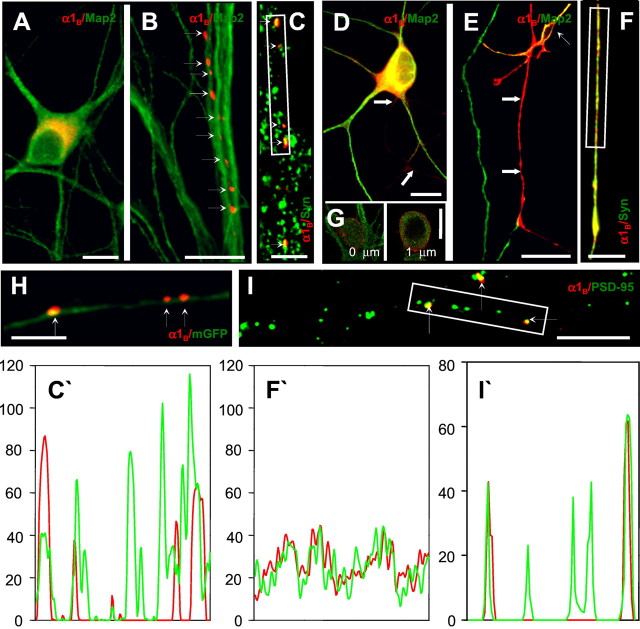

Fig. 2.

Distribution of recombinant N-type channels in mature hippocampal neurons. Neurons cultured at high (A–C, H, I) or low (D–G) density were transfected with an HA-α1B/α2δ/β3plasmid combination at 10 DIV and analyzed 96 hr after transfection.A, B, Staining for HA-α1B(red) and MAP2 (green) of hippocampal neurons cultured at high density for 14 d (14 DIV). The recombinant channels are primarily excluded from somatodendritic domain (A) and concentrated in discrete clusters apposed to dendrites of nontransfected cells (B,small arrows). Scale bars, 20 μm. C, Colocalization of HA-α1B clusters (red,small arrows) with clusters of endogenous synapsin (green) in axons of 14 DIV hippocampal neurons cultured at high density. The fluorescence intensity profile (C′; HA, red; synapsin, green) is taken from the boxed area in C. HA-negative clusters of synapsin correspond to synaptic terminals of nontransfected neurons in the field of view. Scale bar, 10 μm.D, E, Staining for HA-α1B(red) and MAP2 (green) of neurons cultured at low density for 14 d. The N-type channels are present in the somatodendritic domain (D) and uniformly distributed in axons (E). The axons (large arrows) are identified as MAP2-negative processes. Weak HA-α1B immunoreactivity is observed in the proximal axonal segment (D), but a strong HA signal was observed in distal parts of axons (E) and growth cones (data now shown). In E, a dendrite (MAP2-positive) of a neighboring transfected cell in indicated by a small arrow. Scale bars, 20 μm. F, Distribution of recombinant HA-α1B (red) and endogenous synapsin (green) in axons of 14 DIV hippocampal neurons cultured at low density. The fluorescence intensity profile (F′; HA, red; synapsin,green) is taken from the boxed area inF. Scale bar, 10 μm. G, Confocal analysis of recombinant HA-α1B localization in the soma of mature neurons cultured at low density. HA-α1B is shown in red; MAP2 is in green. Images were collected as described in Figure 1D and Materials and Methods. Two representative images from the stack are shown. H, Axon of a neuron cotransfected with HA-α1B/α2δ/β3(red) and mGFP (green). Clusters of HA-α1B are indicated by small arrows. Scale bar, 10 μm. I, Clusters of recombinant HA-α1B (red) and endogenous PSD-95 (green) colocalize (small arrows). The fluorescence intensity profile (I′; HA,red; PSD-95, green) is taken from theboxed area in I. HA-negative clusters of PSD-95 correspond to synaptic terminals of nontransfected neurons in the field of view. Scale bar, 10 μm.

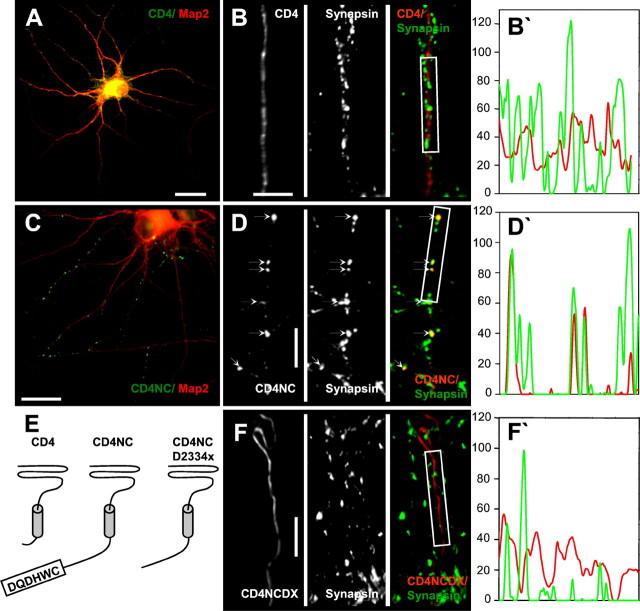

Fig. 3.

Structural determinants of recombinant N-type channel synaptic targeting. A–D, The wild-type (WT) HA-α1B subunit (A) and C-terminal mutants HA-α1B-T2038X (B), HA-α1B-D2334X (C), or HA-α1B-PXXP-A/D2334X (D) cotransfected with α2δ-1 and β3 subunits into high-density hippocampal neurons at 10 DIV. At 4 d after transfection, the axonal distribution of HA-α1B(red) and endogenous synapsin (green) was compared. The fluorescence intensity profiles of the boxed regions are shown on theright. In A and C, HA-α1B clusters are indicated by small arrows. The domain structure of the α1BC-terminal domain is shown on the left (proline-rich region, striped box; PDZ domain-binding motif,black box; PXXP-A mutation, gap instriped box). Scale bars, 10 μm. E, The recombinant N-type channels (HA-α1B/α2δ/β3) were cotransfected with GFP-NC3 construct (GFP fused to 2021–2339 aa of α1B) into high-density hippocampal neurons at 10 DIV. At 4 d after transfection, the localization of HA-α1B (red), GFP-NC3 (green), and endogenous synapsin (blue) was determined. The fluorescence intensity profiles of the boxed region for HA-α1B(red), GFP-NC3 (green), and synapsin (blue) are on the right. The domain structure of the HA-α1B and GFP-NC3 constructs is shown on the left. Scale bar, 10 μm.F, Quantitative analysis of HA-α1Bwild-type and C-terminal mutant axonal distribution. Based on visual examination, for each transfected neuron the axonal distribution of HA-α1B was scored as clustered or diffuse. The percentage of transfected neurons with clustered axonal distribution of HA-α1B was calculated for each transfection. The data from at least two independent transfections for each construct are presented as mean ± SD, with the total numbers of analyzed cells shown on the top. For D2334X and PXXP-A mutants, thep values (when compared with the wild type) are <0.002 and 0.01, respectively (indicated byasterisks).

Fig. 6.

Synaptic targeting of CD4-NC construct. CD4, CD4-NC, and CD4-NC-D2334X chimeric constructs were transfected into high-density rat hippocampal neurons at 10–11 DIV, and their subcellular localization was visualized by immunostaining with CD4 or CD4-FITC antibodies 3–4 d after transfection. A, C, MAP2 (red) and CD4 (green) staining of high-density hippocampal neuronal cultures transfected with CD4 (A) and CD4-NC (C). Scale bars, 20 μm. B, D, F, CD4 (left panel, red in merged image) and synapsin (center panel, green inmerged image) localization in axons of neurons transfected with CD4 (B), CD4-NC (D), or CD4-NC-D2334X (F). CD4 clusters are indicated by small arrows(D). CD4-negative clusters of synapsin correspond to synaptic terminals of nontransfected neurons in the field of view. The fluorescence intensity profiles (CD4, red; synapsin,green) of the boxed regions inB, D, and F are shown onB′, D′, and F′, respectively. Scale bars, 10 μm. E, Topological models of CD4, CD4-NC, and CD4-NC-D2334X targeting constructs.

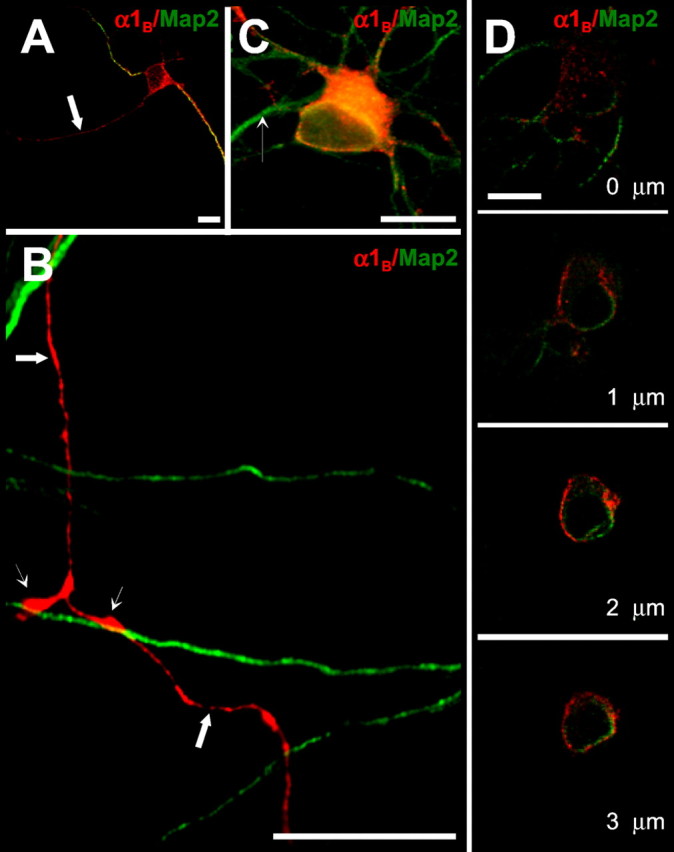

Fig. 1.

Distribution of recombinant N-type channels in immature hippocampal neurons. Hippocampal neurons cultured in high density were transfected with a mixture of HA-α1B/α2δ/β3 cDNAs 2 d after plating. At 4 d after transfection, the neurons were fixed, permeabilized, and labeled with monoclonal anti-HA (red) and polyclonal anti-MAP2 (green) antibodies for conventional (A–C) and confocal (D) imaging. Scale bars, 20 μm. A, Recombinant HA-α1B is targeted to both axons (arrow, MAP2-negative) and dendrites (MAP2-positive processes) of immature neurons. B, Recombinant HA-α1B is uniformly distributed in axons of transfected neurons (large arrows, MAP2-negative), with some degree of enrichment in zones of contacts between axons and dendrites of neighboring nontransfected cells (small arrows, MAP2-positive). C, Recombinant HA-α1B is present in cell bodies and dendrites of transfected neurons. The dendrite of a neighboring untransfected cell is indicated by a small arrow. Only weak HA immunoreactivity was typically observed in the proximal axonal segment. D, Confocal analysis of recombinant HA-α1B localization in the soma. Stacks of images were collected starting from the surface of the cell with 0.2 μm thickness. Every fifth image from the stack is shown.

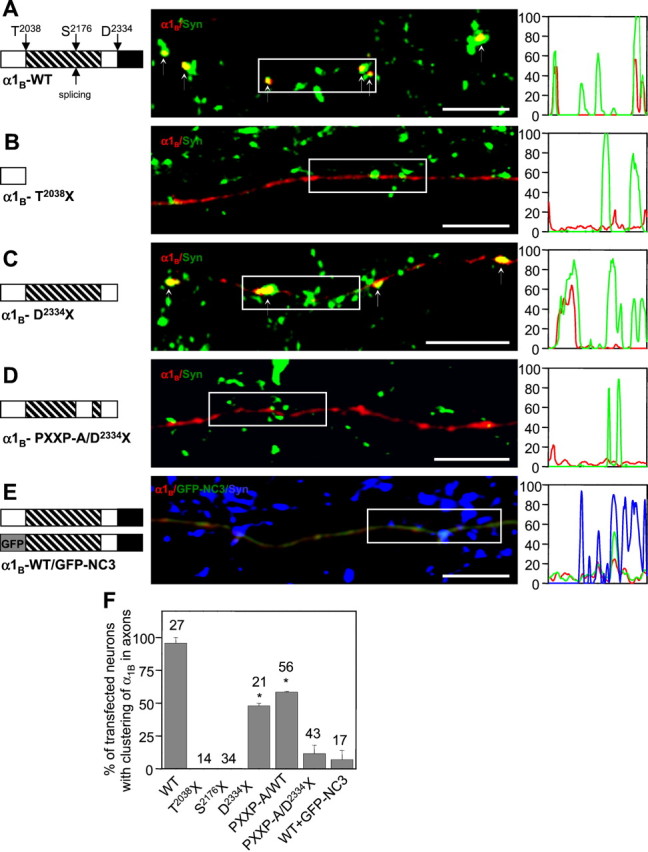

Fig. 4.

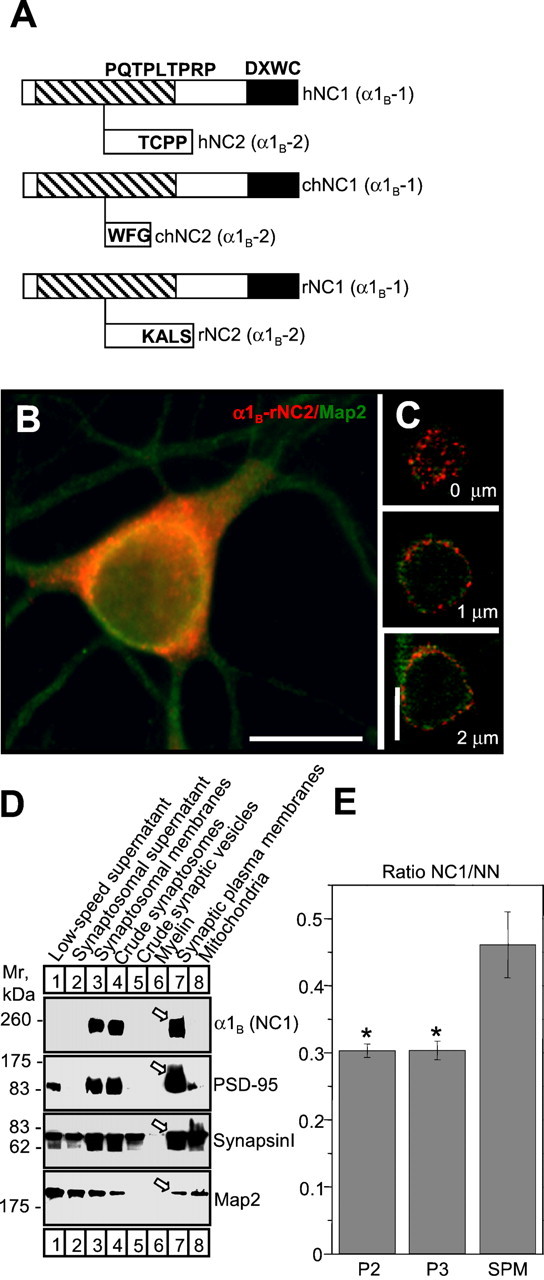

Cloning and subcellular localization of rat α1B-NC2 splice variant.A, Diagram of human (Williams et al., 1992), chicken (Lu and Dunlap, 1999), and rat α1B C-terminal splice variants. The sequence of rat α1B-NC2 has been deposited in GenBank (accession number AF389419). The position of PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs is indicated as in Figure 3A.B, Recombinant HA-α1B-rNC2 (red) and endogenous MAP2 (green) localization in mature neurons cultured at high density. Scale bars, 20 μm. C, Confocal analysis of recombinant HA-α1B-rNC2 localization in the soma of mature neurons cultured at low density. Three representative images from the stack are shown. D, Western blot of rat brain subcellular fractions with antibodies against rat α1B-NC1 and the neuronal markers PSD-95, synapsin I, and MAP2. Equal amounts of protein were loaded to each lane. Arrowsindicate samples on the synaptic plasma membrane fraction.E, The ratio of 125I-ω-GVIA binding site amounts precipitated by NC1 and NN antibodies from P2, P3, and SPM fractions solubilized in CHAPS. *p < 0.001.

Subcellular fractionation of brain. Subcellular brain fractions were isolated as described previously (Jones and Matus, 1974). Briefly, 12 rat brains were homogenized in 0.32m sucrose and 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, and centrifuged for 10 min at 800 × g to remove the nuclei. The low-speed supernatant was then centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000 × g to separate synaptosomal supernatant and synaptosomal membrane fractions (P2 pellet). P2 pellets were incubated for 30 min at 4°C in hypotonic lysis buffer containing 5 mm Tris, pH 7.2, and then centrifuged at 25,000 × g to separate synaptic vesicles and crude synaptosomal fractions (P3 pellet). P3 pellets were adjusted to 1.1m sucrose, loaded to the centrifuge tubes, and layered by solutions of 0.86 and 0.32 m sucrose. Subcellular fractions were separated by centrifugation of samples for 2.5 hr at 48,000 × g. For Western blot analysis, equal amounts of protein were loaded to each lane.

Immunoprecipitations. Samples of synaptosomal membranes, crude synaptosomes, and synaptic plasma membranes (SPMs) were solubilized in buffer containing 1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 10% glycerol, 0.16m sucrose, and protease inhibitors for 2 hr at 4°C. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation of samples for 20 min at 100,000 × g. Samples were prelabeled with 5 nm125I-ω-GVIA (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 1 hr at 4°C and then incubated with protein A-Sepharose beads covered with NN or NC1 antibodies or corresponding preimmune serum for 2 hr at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with the fivefold diluted solubilization buffer, and the number of 125I-ω-GVIA binding sites precipitated by each antibody was measured with a gamma counter. Data were normalized to the total protein content in each fraction. Nonspecific binding measured with preimmune serum was subtracted from the data.

Cloning of rNC2. Rat brain polyA RNA was isolated (STAT-60; Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX), and cDNA was generated from poly-dT primer with a RETROscript kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Obtained cDNA was used as a template for nested PCR with two pairs of primers specific for rat α1B sequence (Q2294) FP1 = GCGCAGGGACAAGAAGCAGA, RP1 = CTAGCACCAGTGATCCTGGTCT; FP2 = CAGAGAAGCAGCGCTTCTATTCCT; RP2 = TCTGGGTGGTGGTAGCTGTG. The products of nested PCR were separated on agarose gel, purified, subcloned into pCR2.1 Topo plasmid (Invitrogen), and sequenced. The novel sequence of rNC2 splice variant was deposited into GenBank (accession numberAF389419).

RESULTS

Distribution of N-type Ca2+ channels in immature rat hippocampal neurons

To study N-type Ca2+ channel targeting in neurons, we added HA tag to an N terminal of the long C-terminal splice variant of the human N-type channel pore-forming subunit α1B-1 (CaV2.2a) (Williams et al., 1992; Ellinor et al., 1994; Ertel et al., 2000) and expressed the resulting HA-α1B construct in rat hippocampal neurons by Ca2+phosphate-mediated transfection (see Materials and Methods). When expressed without auxiliary subunits, the HA-α1B construct was restricted to neuronal soma (data not shown), most likely because of retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Bichet et al., 2000). Thus, in all experiments in this study the HA-α1B construct was coexpressed with the rabbit α2δ-1 (Mikami et al., 1989) and rabbit β3 (Hullin et al., 1992) subunits. We first analyzed distribution of recombinant N-type channels expressed in immature neurons [5–6 d in vitro(DIV)], before maturation of synaptic contacts and formation of a fully polarized phenotype. Both morphological criteria and MAP2 staining were used to discriminate between somatodendritic and axonal compartments of immature neurons in these experiments. The recombinant HA-α1B was detected in both somatodendritic and axonal domains of immature neurons (Fig. 1A,C). The recombinant N-type channels present in axons were diffusely distributed with some degree of enrichment in zones of contacts between axons and dendrites of neighboring nontransfected cells (Fig.1B). Similar results were obtained with another α1B construct in which HA tag was inserted into the intracellular loop between II and III repeats (data not shown). Thus, targeting of N-type channels in neurons is not likely to be affected by addition of the N-terminal HA tag.

Overexpression of recombinant N-type channels in neurons may lead to an artificially strong signal from the channels retained in somatic intracellular compartments, primarily the ER. Surface labeling experiments can help to visualize channels in the plasma membrane. We attempted to incorporate surface-accessible myc tag into several putative extracellular loops in the α1Bsequence, but these constructs could not be detected by anti-myc antibodies in neuronal surface labeling experiments (data not shown). Presumably, myc epitope in these positions is not accessible to the antibody. Instead, we used confocal imaging to determine subcellular localization of the HA-α1B subunit. As expected from theXenopus oocyte expression experiments (see Materials and Methods; Table 1), obtained images were not consistent with the ER-trapped HA-α1B subunit (Fig.1D). Thus, we concluded that recombinant N-type channels are uniformly distributed in immature hippocampal neurons, in agreement with the previously reported studies of native N-type channel distribution in immature hippocampal neurons using immunolocalization (Bahls et al., 1998) and functional (Pravettoni et al., 2000) methods.

Distribution of N-type Ca2+ channels in mature rat hippocampal neurons

Neuronal contact-dependent clustering of endogenous N-type Ca2+ channels (Bahls et al., 1998) and synapsins (Fletcher et al., 1991) in synaptic sites has been described for mature high-density cultures of rat hippocampal neurons. Thus, we subsequently examined the distribution of recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels (HA-α1B/α2δ/β3) in high-density mature (14 DIV) rat hippocampal neuronal cultures. In contrast to experiments with immature cultures, we found that in mature cultures HA-α1B was primarily absent from soma and dendrites (Fig. 2A). Indeed, in 90 ± 5% (n = 110; five independent transfections) of neurons only weak HA immunoreactivity was detected in soma and proximal dendrites (Fig. 2A). Recombinant N-type channels expressed in mature neuronal cultures were concentrated in discrete clusters apposed to dendrites of nontransfected cells (Fig.2B). When the neurons were cotransfected with recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels and the membrane-associated form of GFP (mGFP) (Moriyoshi et al., 1996), the HA-α1B-positive clusters were associated with the long, fine caliber fibers visualized by mGFP fluorescence (Fig.2H). The latter observation rules out the possibility that the clusters of HA-α1B represent protein aggregates formed because of toxicity or fragmentation of neuronal processes. The morphology of neuronal processes visualized by mGFP fits with the expected morphology of axonal processes at the corresponding stage of neuronal culture (Fletcher and Banker, 1989). The HA-α1B-positive clusters were localized to contacts between axon (MAP2-negative) and dendrites (MAP2-positive) processes (Fig. 2B). The HA-α1B-positive clusters were also precisely colocalized with the clusters of endogenous synapsin (Fig.2C,C′) and endogenous PSD-95 (Fig. 2I,I′), visualized by the corresponding polyclonal antibody. From all of these results, we concluded that the recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels expressed in mature neuronal cultures are concentrated in axons and clustered at presynaptic locations.

Distribution of recombinant N-type channels was diffuse and uniform in immature, low-density neuronal cultures (Fig. 1A,B) and punctate and polarized in mature, high-density cultures (Fig.2A–C,H,I). Is distribution of recombinant N-type channels in neurons affected by the age of neuronal culture or by the formation of synapses? To answer this question, we transfected low-density rat hippocampal neuronal cultures at 10 DIV with the HA-α1B/α2δ/β3subunit combination and analyzed HA-α1Blocalization 4 d after transfection. At the same age of culture, the number of synaptic contacts formed by each cell in the low-density culture was significantly reduced when compared with the high-density culture. The N-type channels expressed in the low-density mature cultures were diffusely distributed in soma, dendrites, and axons of transfected neurons (Fig. 2D,E). Using confocal imaging, we demonstrated that the immunoreactivity in the somatic compartment does not result from ER-trapped HA-α1B protein (Fig. 2G). Axons in these experiments can be easily identified as HA-α1B-positive MAP2-negative processes (Fig.2E). In agreement with previous findings (Fletcher et al., 1991), distribution of endogenous synapsins in axons of these neurons had a granular appearance (Fig. 2F), in marked contrast to distinct clusters of synapsin observed in mature high-density cultures (Fig. 2C). Distribution of HA-α1B in axons of neurons cultured at low density was similar to distribution of synapsin (Fig.2F,F′). We concluded from these experiments that neuronal contacts and synapse formation are essential for recombinant N-type Ca2+ channel clustering in hippocampal neurons. It also appears that not only synaptic clustering but also polarized distribution of recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels depends on neuronal contacts (Fig. 2A,D). The latter conclusion is unexpected and challenges a common view that polarized protein targeting in neurons is guided by intrinsic sorting signals and happens independently of cell-to-cell contacts (Craig and Banker, 1994).

Structural determinants of N-type Ca2+ channel targeting to synapse

In the next series of experiments, we searched for the structural determinants responsible for N-type Ca2+channel targeting to synapses. In the previous biochemical studies, we identified SH3 and PDZ domain-binding motifs in the C-terminal region of the long splice variant of a human N-type Ca2+ channel pore-forming subunit, α1B-1 (CaV2.2a) (Maximov et al., 1999). We discovered (Maximov et al., 1999) that Mint1-PDZ1 binds to the C termini of the α1B subunit (Fig.3A, black box,diagram), and that CASK-SH3 binds to the proline-rich region ∼300 aa upstream of the α1B C termini (Fig.3A, dashed box, diagram). The same proline-rich region has been also implicated in interactions with G-protein βγ subunits (Qin et al., 1997), with the auxiliary Ca2+ channel β subunit (Walker et al., 1998) and more recently with the SH3 domain of the Rab3-interacting molecule (RIM)-binding protein (RBP) (Hibino et al., 2002). We hypothesized previously that the identified PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs may play a role in N-type Ca2+channel synaptic targeting in neurons (Maximov et al., 1999). To test this hypothesis, a series of C-terminal mutants of HA-tagged α1B subunit was generated and expressed in mature, high-density hippocampal cultures (Fig. 3). The α1B mutants used in these experiments were expressed at levels similar to the wild-type channels when transfected into COS7 or HEK293 cells and supported functional Ca2+ currents of similar size when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (see Materials and Methods; Table 1).

As discussed in the previous section, the wild-type HA-α1B subunit expressed in mature high-density cultures was localized in clusters along axonal processes and precisely colocalized with endogenous synapsins (Fig. 3A). Axonal clustering of the wild-type HA-α1B subunit was observed in 95 ± 3% (n = 27) of transfected neurons (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the HA-α1B-T2038X truncation mutant was diffusely distributed along the axonal processes (Fig. 3B,F). Thus, the last 301 aa of the α1B sequence (amino acids 2038–2339) did indeed contain motifs essential for synaptic targeting of recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons. To determine the role played by the PDZ domain-binding motif, we generated the HA-α1B-D2334X mutant that lacks the last 6 C-terminal amino acids of the α1B sequence. When the HA-α1B-D2334X mutant was expressed in neurons, it also formed synaptic clusters along the axonal processes (Fig. 3C). The synaptic clustering of the HA-α1B-D2334X mutant was observed only in 48 ± 3% (n = 21) of transfected cells (Fig.3F), indicating partial impairment of channel targeting caused by C-terminal truncation.

Alternative splicing of human α1B C termini occurs within the proline-rich region at position 2163 (Williams et al., 1992). The HA-α1B-S2176X mutant, truncated close to the alternative splicing site of human α1B subunit, is diffusely distributed in axons of transfected neurons (Fig. 3F). We noticed that a strong class I SH3 domain-binding consensus2188RQLPQTPLTPRP2199(Dalgarno et al., 1997; Mayer, 2001) is present in the α1B-1 (CaV2.2a) but not in the α1B-2 (CaV2.2b) isoform of the human subunit. We reasoned that this motif may play an important role in channel targeting and replaced its portion (amino acids 2191–2199) with the polyalanine sequence (PXXP-A mutation) (Fig.3D, diagram, gap). In control biochemical experiments, we established that the region of α1B subunit involved in association with the β3 subunit lies upstream of the area affected by the PXXP-A mutation (data not shown). Notably, the PXXP-A mutation is expected to affect the association of α1Bsubunit with the RBP-SH3 domain, which binds to the same motif (Hibino et al., 2002). When the HA-α1B-PXXP-A mutant was expressed in mature neuronal cultures, synaptic clustering of recombinant channels was observed in 59 ± 1% of transfected cells (Fig. 3F). Thus, the phenotype of the HA-α1B-PXXP-A mutant is very similar to the phenotype of the HA-α1B-D2334X mutant; in both cases, the channels are clustered at synapses, albeit not as efficiently as the wild-type channel (Fig. 3F).

To further investigate the targeting function of PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs in the α1B C-terminal region, we combined the PXXP-A and D2334X mutations. When the resulting HA-tagged double mutant was expressed in hippocampal neurons, diffuse distribution of recombinant N-type channels in axons was observed (Fig.3D), similar to the HA-α1B-T2038X truncation mutant (Fig. 3B). Axonal clusters were observed only in 12 ± 9% of neurons transfected with the HA-α1B-PXXP-A/D2334X double mutant (Fig.3F). Thus, deletion of a 6-aa-long PDZ domain-binding consensus (2334–2339) and mutation of a 9-aa-long SH3 domain-binding consensus (2191–2199) to polyalanines results in an almost complete loss of the ability of the N-type channel to cluster at synapses in hippocampal neurons. We concluded that PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs in α1B-1 C termini act as synergistic synaptic targeting signals, and that the presence of at least one of these motifs is necessary for synaptic targeting of N-type Ca2+ channels.

The most likely explanation for our results is that interaction of the α1B subunit with endogenous adaptor proteins containing PDZ and SH3 domains is required for synaptic targeting of N-type channels. If this is indeed the case, then overexpression of the C-terminal portion of the α1B subunit that contains the PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs in neurons should result in competition for adaptor proteins and cause mislocalization of N-type channels. To test this hypothesis, we coexpressed the GFP-NC3 construct (GFP fused to the α1B fragment between amino acids 2021–2339) (Fig. 3E, diagram) with HA-tagged recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels (HA-α1B/α2δ/β3) in mature (14 DIV) neuronal cultures. In agreement with our prediction, the formation of HA-positive clusters but not clusters of endogenous synapsins was abolished in GFP-NC3-expressing axons (Fig.3E,F). The effect of GFP-NC3 was specific, because coexpression with mGFP did not interfere with synaptic clustering of recombinant N-type channels (Fig. 2H). We reasoned that GFP-NC3 exerts its dominant-negative effect by displacing HA-α1B from complexes with endogenous adaptor proteins involved in synaptic cluster formation.

Alternative splicing of rat α1B subunit

The phenotypes of HA-α1B-S2176X (Fig.3F) and HA-α1B-PXXP-A/D2334X (Fig. 3D,F) mutants suggest that only the long α1B-NC1 (α1B-1, CaV2.2a) but not “short” α1B-NC2 (α1B-2, CaV2.2b) splice variant of α1B subunit should be targeted to synapses. To test this hypothesis experimentally, we set out to clone the rat α1B-NC2 splice variant (rNC2). The short C-tail splice isoform of rat α1B was observed in biochemical experiments (Hell et al., 1994), but only the rNC1 isoform sequence is present in the GenBank database. By standard molecular techniques, we isolated rat brain mRNA, synthesized cDNA from oligo-dT primer, and performed a nested PCR with two pairs of rat α1B-specific primers (see Materials and Methods). Two distinct products obtained as a result of a nested PCR were isolated, subcloned, and sequenced. One product corresponded to a known rNC1 isoform of rat α1B subunit (Dubel et al., 1992). Another product corresponded to a novel rNC2 (α1B-2, CaV2.2b) isoform (GenBank accession number AF389419). Interestingly, the position of the C-terminal splicing site and the sequence of α1B-NC1 isoform is highly conserved between human (Williams et al., 1992), chicken (Lu and Dunlap, 1999), and rat (Fig. 4A) clones, whereas the sequence of the α1B-NC2 isoform after the splicing site is divergent between species.

To obtain information about localization of the α1B-NC2 isoform in neurons, we fused the C-terminal tail of the short rat α1B-NC2 splice variant with the HA-tagged human α1B clone. The resulting HA-α1B-rNC2 construct was coexpressed with auxiliary α2δ and β3 subunits in immature (5–6 DIV) (data not shown) and mature (14 DIV) (Fig. 4B) high-density rat hippocampal neurons. We found that the short HA-α1B-rNC2 splice variant was primarily excluded from axons of both immature (data not shown) and mature neurons and formed aggregates in neuronal soma and proximal dendrites (Fig. 4B). Confocal image analysis (Fig.4C) and Xenopus oocyte expression experiments (see Materials and Methods; Table 1) confirmed that the HA-α1B-rNC2 protein was not trapped in the ER. The localization of the HA-α1B-rNC2 isoform in mature high-density neuronal cultures differs dramatically from the localization of the HA-α1B-NC1 isoform (Fig.2A–C). The distribution of HA-α1B-rNC2 also differs from the distribution of HA-α1B-T2038X and HA-α1B-S2176X truncation mutants, which were diffusely and uniformly distributed in both axonal (Fig.3B,F) and somatodendritic (data not shown) domains. Thus, somatodendritic retention and aggregation motifs are likely to be encoded by C termini of the α1B-NC2 splice variant. From these results, we concluded that the α1B-NC1 (α1B-1, CaV2.2a) splice variant encodes the axonal/synaptic isoform, and that the α1B-NC2 (α1B-2, CaV2.2b) splice variant encodes the somatodendritic isoform of the N-type Ca2+ channels.

To test this hypothesis further, we generated NC1 splice-variant-specific antibodies against the C-terminal region of the rat α1B subunit (see Materials and Methods). Generated NC1 antibodies were not appropriate for immunostaining of hippocampal cultures (data not shown). However, NC1 antibodies could be used for Western blotting and immunoprecipitation experiments. To analyze the subcellular distribution of the NC1 splice variant, we fractionated rat brain cortical homogenate (Jones and Matus, 1974) and analyzed the resulting fractions by Western blotting with NC1 antibodies (Fig. 4D, first row), PSD-95 antibodies (Fig. 4D, second row), synapsin I antibodies (Fig. 4D, third row), and MAP2 antibodies (Fig. 4D, fourth row). We found that the distribution of NC1 immunoreactivity was parallel to that of PSD-95 (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the endogenous NC1 splice variant is concentrated in synaptic locations. What is a relative distribution of NC1 and NC2 splice variants? We could not generate NC2-specific antibodies to address this question directly. Instead, we performed experiments with NN antibodies directed against the N-terminal region of the rat α1Bsubunit (Maximov et al., 1999). The NN antibodies recognized both C-terminal splice variants of the rat α1Bsubunit. To quantify the relative distribution of NC1 and NC2 splice variants, in the next series of experiments we compared the relative ability of NC1 and NN antibodies to immunoprecipitate125I-ω-GVIA-labeled N-type Ca2+ channels from different subcellular fractions. We found that the fraction of125I-ω-GVIA binding sites precipitated by NC1 antibodies from the SPM fraction was significantly elevated when compared with P2 and P3 fractions (Fig. 4E). Thus, we concluded that the NC1 splice variant is enriched in synaptic locations in comparison with the NC2 splice variant.

Dominant negative effects of α1B C termini on synaptic function

The C-terminal GFP-NC3 construct disrupts the synaptic clustering of recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels (Fig.3E,F). In the next series of experiments, we analyzed the effects of GFP-NC3 overexpression on synaptic function. To measure synaptic activity, we monitored the depolarization-induced uptake of antibodies against the lumenal domain of STI in synapses of hippocampal neurons. In these experiments, we followed the previously described STI labeling procedure (Matteoli et al., 1992) (Fig. 5A). The STI antibodies, trapped inside endocytosed synaptic vesicles, report locations of synapses capable of depolarization-induced exocytosis. Opening of synaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ influx into the presynaptic terminal is an essential step leading from depolarization to exocytosis. When extracellular Ca2+ was omitted from depolarization media, no signal with STI antibodies was observed in response to KCl depolarization (data not shown). In additional control experiments, we demonstrated that STI-positive clusters were concentrated in points of contact between axons and the MAP2-positive postsynaptic target (Fig. 5B), and that STI- and synapsin-positive clusters were colocalized (Fig. 5C), confirming the specificity of the STI staining pattern.

To test the effect of GFP-NC3 overexpression on synaptic function, we compared the signal reported by STI antibodies for nontransfected (control) neurons and for neurons transfected with GFP-NC3 or mGFP. When compared with control neurons, we observed a significant reduction in the intensity of individual STI-positive clusters in axons expressing GFP-NC3 (Fig. 5D,D′) but not in axons expressing mGFP (Fig. 5E). On average, the intensity of STI-positive clusters was 40% weaker in axons of GFP-NC3-transfected cells than in the axons of nontransfected or mGFP-expressing cells (Fig.5F). The effect of GFP-NC3 on STI staining was not caused by loss of the ability of the axons of transfected neurons to form synaptic contacts, because synapsin and PSD-95 staining was not affected by GFP-NC3 overexpression (Fig. 5F). A similar conclusion can be drawn by comparing the cumulative distribution of individual STI cluster intensities between control, mGFP-expressing, and GFP-NC3-expressing neurons (Fig. 5G). We reasoned from these data that depolarization-induced exocytosis is suppressed in synapses of neurons overexpressing GFP-NC3 but not mGFP construct. To explain these results, we reasoned that depression of synaptic function by the GFP-NC3 construct is caused by its interference with targeting and/or the synaptic function of endogenous Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neuronal cultures.

Overexpression of GFP-NC3 completely abolished the clustering of recombinant N-type channels (Fig. 3E,F) but had only a partial effect on the synaptic activity reported by STI antibody uptake (Fig. 5F). Previous experiments with FM1–43 imaging dye indicated that in hippocampal neuronal cultures ∼45% of synapses rely solely on N-type Ca2+channels; the remaining 55% are supported by a mixture of N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (Reuter, 1995). One possible explanation for the partial effect of GFP-NC3 on STI antibody uptake is that GFP-NC3 causes only partial suppression of endogenous N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel function at synapses. An alternative explanation is that GFP-NC3 interferes with the synaptic function of N-type but not P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. To discriminate between these possibilities, we compared effects of GFP-NC3 on STI antibody uptake after preincubation of neuronal cultures with 5 μm ω-GVIA or 5 μmω-MVIIC conotoxins. The ω-GVIA conotoxin is a selective inhibitor of N-type Ca2+ channels (Boland et al., 1994), whereas ω-MVIIC conotoxin blocks both N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (McDonough et al., 1996). The block of N-type Ca2+ channels by ω-MVIIC is rapidly reversible, with the time constant of ∼30 sec (McDonough et al., 1996). In contrast, the block of P/Q-type channels by ω-MVIIC and the block of N-type Ca2+channels by ω-GVIA reverses on a time scale of hours (Boland et al., 1994; McDonough et al., 1996). We took advantage of these kinetic differences in the design of our experiments. Before exposure of hippocampal neuronal cultures to KCl and STI antibody, we removed the toxins and washed the cultures for 3–5 min in PBS. During the wash period, the block of N-type channels by ω-MVIIC, but not the block of P/Q-type channels by ω-MVIIC or the block of N-type channels by ω-GVIA, was reversed. Thus, in our experiments P/Q-type Ca2+ channels were selectively blocked by ω-MVIIC conotoxin during KCl stimulation and STI labeling. The latter conclusion was supported by our observation that the mixture of both ω-GVIA and ω-MVIIC conotoxins abolished STI clusters in our cultures (data not shown), whereas a large number of STI clusters were observed in the presence of ω-GVIA or ω-MVIIC conotoxins alone. When cultures were preincubated with either ω-GVIA or ω-MVIIC conotoxins, overexpression of GFP-NC3 caused a significant suppression of the average intensity of observed STI clusters when compared with nontransfected neurons (Fig. 5H). From these data, we concluded that GFP-NC3 has similar inhibitory effects on the synaptic function of either N-type or P/Q-type Ca2+channels, and that the synaptic function of endogenous Ca2+ channels is only partially disrupted by GFP-NC3 overexpression in hippocampal neuronal cultures.

Synaptic targeting of CD4-α1B-NC chimeric constructs in hippocampal neurons

In the previous sections, we established that the C-terminal region of the α1B subunit (amino acids 2177–2339) is necessary for synaptic clustering of N-type Ca2+ channels in mature high-density neuronal cultures. Are N-type Ca2+ channel C termini also sufficient for synaptic targeting? To answer this question, we generated a model chimeric construct, CD4-NC, composed of an extracellular human CD4 receptor ectodomain, a single human CD4 receptor transmembrane domain, and a short fragment of human α1B cytosolic tail (Fig.6E,diagram). In the resulting CD4-NC construct, most of the α1B-NC1 C terminus, including the proline-rich region, was removed from the sequence, leaving the short region in the beginning of the C-tail and the most C-terminal region containing the PDZ domain-binding consensus. To evaluate the role of the PDZ domain-binding motif, the control CD4-NC-D2334X construct, which lacked the last 6 aa, was also generated (Fig. 6E,diagram). The human truncated CD4 receptor construct (CD4) served as a negative control in these experiments.

The CD4, CD4-NC, and CD4-NC-D2334X constructs were transfected into mature high-density rat hippocampal neurons. Double labeling with CD4-FITC and MAP2 antibodies demonstrated that the expressed CD4 receptor was diffusely distributed in all processes of transfected cells (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the CD4-NC protein was clustered in axons (Fig. 6C). Double labeling with monoclonal CD4 and polyclonal synapsin antibodies revealed that CD4-NC clusters colocalize with synaptic sites (Fig. 6D,D′). In contrast, diffuse distribution of CD4 immunoreactivity did not correlate with synapsin localization (Fig. 6B,B′). The presence of the PDZ domain-binding motif appears to be essential for synaptic clustering of CD4-NC, because the CD4-NC-D2334X construct was diffusely distributed and did not colocalize with synapsin (Fig.6F,F′). It is important to note that the CD4-NC and CD4-NC-D2334X constructs lack a proline-rich region (amino acids P2039-P2194) in their sequence, which probably accounts for the differences observed in HA-α1B-D2334X and CD4-NC-D2334X distribution (Figs. 3C, 6F). Indeed, a diffuse axonal distribution of the CD4-NC-D2334X construct (Fig. 6F) is similar to diffuse localization of the HA-α1B-PXXP-A/D2334X double mutant (Fig.3D). It is interesting to note that the soluble GFP-NC3 construct was diffusely distributed in hippocampal neurons (Figs.3E, 5D), indicating that the presence of the transmembrane domain in the CD4-NC construct is essential for synaptic targeting. From experiments with the CD4-NC targeting constructs, we concluded that the C-terminal region of α1B is sufficient for targeting of the CD4 receptor to the presynaptic sites in mature high-density hippocampal neuronal cultures. In the absence of the proline-rich region, the synaptic targeting function of α1B C termini is completely determined by the presence of the PDZ domain-binding motif.

The PDZ domain-binding motif is conserved between α1B and α1Apore-forming subunits (Maximov et al., 1999). Does the C terminal of the α1A subunit also act as synaptic targeting signal? To answer this question, we generated CD4-QC and CD4-QC-D2501X constructs (see Materials and Methods), expressed these constructs in mature hippocampal neuronal cultures, and performed double labeling with monoclonal CD4 and polyclonal synapsin antibodies. Similar to the CD4-NC construct, we found that the CD4-QC construct was clustered at synaptic locations, whereas the CD4-QC-D2501X construct was diffusely distributed in axons (data not shown). Thus, the PDZ domain-binding consensus at C termini of α1A (P/Q-type Ca2+ channels) also functions as synaptic targeting signal.

Potential role of Mint1 and CASK adaptor proteins in N-type Ca2+ channel targeting to synapse

Our experiments (Figs. 3, 6) established the importance of PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs in α1B C termini for N-type Ca2+ channel synaptic targeting in hippocampal neurons. In a previous paper (Maximov et al., 1999), we demonstrated that the same motifs specifically associate with the Mint1-PDZ1 and CASK-SH3 adaptor domains. To determine whether Mint1 and CASK can play a role in N-type Ca2+channel targeting in neurons, we expressed GFP-tagged Mint1 and CASK in mature high-density hippocampal neuronal cultures. GFP-Mint1 and GFP-CASK were present in both axonal (MAP2-negative) and somatodendritic (MAP2-positive) domains (Fig.7A,C). In axons, GFP-Mint1 and GFP-CASK form distinct clusters (Fig. 7B,D). The observed clusters were juxtaposed to MAP2-positive processes (Fig.7B,D) and precisely colocalized with synapsin clusters (data not shown). Thus, similar to recombinant N-type channels, recombinant Mint1 and CASK are clustered in presynaptic terminals of mature rat hippocampal neurons.

Fig. 7.

Colocalization of recombinant Mint1 and CASK with N-type channels in mature hippocampal neurons. A–D, High-density hippocampal neuronal cultures transfected with GFP-Mint1 (A, B) and GFP-CASK (B, D) plasmids at 9 DIV. At 3–5 d after transfection, the localization of GFP-Mint1 or GFP-CASK (green) and endogenous MAP2 (red) was determined. The somatodendritic domain (A, C) and distal axonal segment (B, D) of transfected cells are shown. Proximal axonal segments are indicated by arrows (A, C). Presynaptic clusters of GFP-Mint1 (B) and GFP-CASK (D) associated with axons of transfected neurons apposed to dendrites (MAP2-positive) are indicated by small arrows. Scale bars, 20 μm. E, F, High-density mature hippocampal neurons cotransfected with HA-α1B/α2δ/β3 and GFP-Mint1 (E) or GFP-CASK (F) at 9 DIV. At 4 d after transfection, the axonal distribution of HA-α1B (top panel,red in merged image) and GFP-Mint1 (E, center panel, green inmerged image) or GFP-CASK (F,center panel, green in merged image) was determined. Synaptic clusters of HA-α1B, GFP-Mint1, and GFP-CASK are indicated bysmall arrows. Axonal growth cones are indicated byasterisks in E. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Do Mint1, CASK, and N-type Ca2+ channels cluster in the same locations? To answer this question, we coexpressed recombinant HA-tagged N-type Ca2+ channels with GFP-Mint1 or GFP-CASK. We found that GFP-Mint1, GFP-CASK, and HA-α1B were coclustered at mature synapses formed by the same cell (Fig. 7E,F). Is it possible that N-type channels clustered at synaptic sites bind GFP-Mint1 and GFP-CASK, leading to their concentration at synapses? To address this question, we coexpressed GFP-Mint1 and GFP-CASK with HA-NC3 construct (HA tag fused to the α1B fragment between amino acids 2021–2339). In interpretation of these experiments, we assumed that the HA-NC3 construct is expressed at levels far above the levels of endogenous N-type Ca2+ channels. If binding of Mint1 and/or CASK to α1B C termini is required for their synaptic clustering, then the soluble HA-NC3 construct is expected to have a dominant negative effect on their synaptic targeting. However, we did not observe any changes in the subcellular distribution of GFP-Mint1 and GFP-CASK in the presence of HA-NC3 (data not shown). Thus, we concluded that Mint1 and CASK are likely to be targeted to synaptic sites independently of their association with N-type Ca2+ channels.

DISCUSSION

Targeting of N-type Ca2+ channels to synaptic locations in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures was investigated in this study. The main conclusions of our paper are: (1) that polarized distribution of N-type Ca2+channels in neurons depends on the formation of synapses; (2) that the C-terminal 163 aa (amino acids 2177–2339) of the long splice variant of the N-type pore-forming subunit α1B(α1B-1, CaV2.2a) is necessary and sufficient for synaptic targeting of N-type Ca2+ channels; (3) that PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs in the α1B C termini constitute synergistic synaptic targeting signals; (4) that somatodendritic and axonal/synaptic isoforms of N-type channels are generated via alternative splicing of α1B C termini; and (5) that it is likely that Mint1 and CASK adaptor proteins play a role in N-type Ca2+ channel synaptic targeting.

Structural determinants of N-type channel synaptic targeting in hippocampal neurons

Polarized sorting of dendritic proteins in neurons appears to be guided by intrinsic sorting signals (Craig and Banker, 1994; Burack et al., 2000; Silverman et al., 2001). The mechanisms involved in targeting of axonal proteins appear to be more diverse. Neuronal sorting of axonal protein neuron–glia cell adhesion molecule (NgCAM) (Burack et al., 2000), the synaptic vesicle components synapsin and synaptophysin (Fletcher et al., 1991), and the presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (mGluR7) (Stowell and Craig, 1999; Boudin et al., 2000) has been investigated previously. It was concluded that the axonal selection of NgCAM happens at the step downstream of vesicular transport, either as a result of selective membrane fusion or selective retention. The axonal sorting of mGluR7 happens by a nonexclusion mechanism with the receptors present in both dendrites and axons (Stowell and Craig, 1999). Targeting of synaptic vesicle proteins appears to proceed as two-step process: initial axonal targeting based on intrinsic sorting signals followed by clustering at presynaptic sites that depend on cell contacts (Fletcher et al., 1991; Craig and Banker, 1994). In our experiments with recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels expressed in immature or low-density hippocampal cultures, we observed uniform distribution of channels in axonal and somatodendritic compartments (Figs. 1,2D). Similar uniform distribution of native N-type channels in immature hippocampal neurons was reported using immunostaining (Bahls et al., 1998) and functional (Pravettoni et al., 2000) methods. In contrast, in mature, high-density cultures recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels (Fig.2A–C,H,I) and mGluR7 (Boudin et al., 2000) were clustered in synapses and primarily excluded from soma and dendrites. Contact-dependent clustering of endogenous N-type Ca2+ channels (Bahls et al., 1998) and synapsin (Fletcher et al., 1991) was described previously. From these results it appears that the targeting of axonal (NgCAM) proteins is guided by intrinsic sorting signals (Burack et al., 2000), but polarized distribution of presynaptic proteins (mGluR7 and N-type Ca2+ channels) depends on cell-to-cell contact and synapse formation.

Human (Williams et al., 1992), chicken (Lu and Dunlap, 1999), and rat (this study) α1B subunits undergo alternative splicing in the C-terminal region. Our results suggest that in mature high-density cultures, the long α1B-NC1 splice variant (α1B-1, CaV2.2a) is the axonal/presynaptic isoform (Fig.2A–C,H,I), and the short α1B-NC2 splice variant (α1B-2, CaV2.2b) is the somatodendritic isoform (Fig. 4B). Similar to the α1B subunit, the P/Q-type channel pore-forming subunit α1A (CaV2.1) is alternatively spliced at the C termini (Zhuchenko et al., 1997). The long C-terminal splice variant of the α1Asubunit (α1A-1, CaV2.1a), but not the short splice variants, contains a similar PDZ domain-binding motif (Maximov et al., 1999). We suggest that the N-type and the P/Q-type Ca2+ channels are targeted to synapses via interactions with a similar or identical set of adaptor proteins. We also suggest that an alternative splicing of the α1B and α1A subunit C termini provides a potential regulatory mechanism of N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel sorting. In the case of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, association of α1A C terminal with an auxiliary β4 subunit (Walker et al., 1998) may play an additional role in synaptic targeting (Wittemann et al., 2000). It is also possible that truncation of SH3, PDZ, and β4 binding motifs in the α1A subunit (Fletcher et al., 1996) may lead to mistargeting of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in the leaner mice, resulting in severe neurological phenotype. A recent report suggested the importance of alternative splicing in the α1A subunit II/III loop region for P/Q-type Ca2+ channel sorting between axonal and somatodendritic compartments of GABAergic cortical neurons (Timmermann et al., 2002). Novel II/III splice variants of human α1B subunit that lack the soluble SNARE-binding synprint site were identified recently (Kaneko et al., 2002). At the moment it is not clear whether alternative splicing of the α1B and α1AII/III loop and C-terminal regions are independent or correlated events, and future studies will be needed to answer this question. However, these data suggest that the alternative splicing-dependent sorting of Ca2+ channels in neurons may be a general phenomenon.

The role of modular adaptor proteins in synaptic targeting of N-type channels

PDZ domain-containing proteins play an important role in protein sorting in polarized cells (Yeaman et al., 1999) and in synaptic organization (Fanning and Anderson, 1996; Kornau et al., 1997; Craven and Bredt, 1998). The PKC-interacting protein-1 (PICK1)-PDZ domain-binding motif in the mGluR7 C terminal is essential for presynaptic clustering of mGluR7 (Boudin et al., 2000). In the case of N-type Ca2+channels, the synaptic targeting function of the PDZ domain-binding motif is synergistic with the function of the upstream SH3 domain-binding motif (Fig. 3C–F), most likely because the corresponding PDZ and SH3 domain-containing adaptor proteins form a complex with each other. Removal of both motifs or expression of a dominant-negative GFP-NC3 construct containing both motifs prevents clustering of recombinant N-type Ca2+ channel (Fig. 3). The same GFP-NC3 construct exerts a dominant-negative effect on synaptic function (Fig.5). Thus, in cases of both mGluR7 receptors and N-type Ca2+ channels, C-terminal-mediated interactions with PDZ domain adaptor proteins are involved in synaptic clustering. Axonal sorting of NgCAM is not likely to use a similar mechanism, because addition of GFP to the NgCAM C terminal did not affect its targeting to axons (Burack et al., 2000).

What adaptor proteins are involved in N-type channel targeting? We reported previously (Maximov et al., 1999) that there was specific association of the α1B C-terminal region with the first PDZ domain in the neuronal adaptor protein Mint1 and with the SH3 domain of the adaptor protein CASK. More recently, we have shown that α1B C termini also bind to INADL-5, PAR6, and MUPP1–9 PDZ domains (Bezprozvanny and Maximov, 2001). The proline-rich region of the α1B C terminal has been implicated recently in interactions with the SH3 domain of RBP (Hibino et al., 2002). Thus, a number of adaptor proteins may play a role in N-type Ca2+ channel synaptic targeting. At present, Mint1 and CASK are the best candidates for an important role in N-type Ca2+ channel synaptic targeting. Indeed, in Caenorhabditis elegans, the tripartite complex of the Mint1 homolog lin-10 with adaptor proteinslin-2 (CASK homolog) and lin-7 (veli homolog) mediates targeting of the LET-23 receptor in polarized epithelia (Rongo et al., 1998). Mint1/CASK/veli forms a homologous complex in the brain (Borg et al., 1998, 1999; Butz et al., 1998). Direct association of Mint1 and CASK may explain the synergism in the synaptic targeting function of the PDZ and SH3 domain-binding motifs in the α1B C termini (Fig. 3). When expressed in neurons, GFP-Mint1 and GFP-CASK clustered at synapses (Fig.7B,D) and colocalized in presynaptic locations with recombinant N-type Ca2+ channels (Fig.7E,F). Recent analysis by electron microscopy reported the presence of endogenous Mint1 in presynaptic terminals (Okamoto et al., 2000). A potential role for Mint1 in targeting of the NMDA receptor to postsynaptic density has also been suggested (Setou et al., 2000), and the Mint1-binding partner CASK has been found on both sides of the synaptic cleft (Hsueh et al., 1998). Thus, it is possible that the Mint1/CASK/veli complex or a similar complex is involved in targeting of ion channels and receptors on both sides of the synapse. A similar conclusion has been drawn regarding the PICK1 protein, implicated in mGluR7 clustering at presynaptic terminals (Boudin et al., 2000), which is found at both sides of the synapse (Torres et al., 1998; Xia et al., 1999). Future experiments, which will likely use the knock-out mice approach, should help to dissect the role played by Mint1, CASK, and other adaptor proteins in Ca2+ channel targeting to the axonal compartment and recruitment to synapses.

The model of N-type channel synaptic targeting in hippocampal neurons

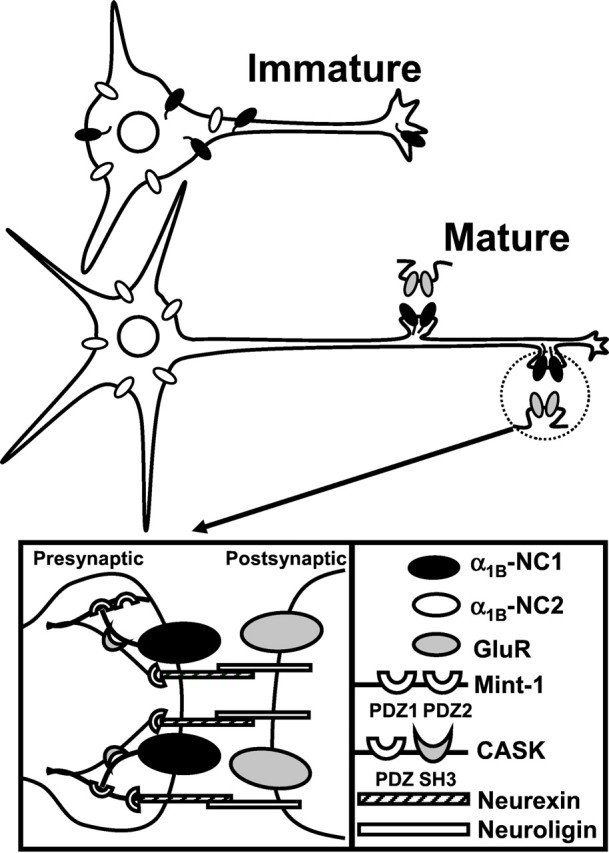

The main conclusions of our study can be summarized in the form of a model (Fig. 8). We suggest that before synaptogenesis, N-type Ca2+ channels containing α1B-NC1 (α1B-1, CaV2.2a) subunit are diffusely and uniformly distributed in both axonal and somatodendritic compartments of immature neurons, whereas α1B-NC2 (α1B-2, CaV2.2b) subunits are only present in neuronal soma and dendrites (Fig. 8, top). After synapse formation, the channels formed by α1B-NC1 subunit are concentrated at axons and clustered at synapses, and the channels formed by α1B-NC2 splice variant are restricted to soma and dendrites (Fig. 8, bottom). Analogous redistribution of native N-type Ca2+channels during synaptogenesis in rat hippocampal neuronal cultures has been suggested previously on the basis of immunolocalization (Bahls et al., 1998) and functional (Pravettoni et al., 2000) experiments. Clustering of N-type Ca2+ channels in synaptic locations appears to be mediated by extrinsic regulatory cues, which most likely involve neuronal adhesion molecules. The Mint1/CASK/veli complex in the brain is associated with the neurexin–neuroligin synaptic junctional complex (Irie et al., 1997;Nguyen and Sudhof, 1997; Butz et al., 1998; Song et al., 1999; Biederer and Sudhof, 2000). Recent results suggest a primary role of neurexin–neuroligin association in the induction of presynaptic differentiation (Rao et al., 2000; Scheiffele et al., 2000). The association of α1B-NC1 C termini with the Mint1/CASK/veli-neurexin/neuroligin complex (Maximov et al., 1999) (Fig. 8, inset) provides a possible molecular mechanism for N-type Ca2+ channel synaptic targeting during synaptogenesis.

Fig. 8.

Model of N-type Ca2+ channel synaptic targeting in neurons. N-type Ca2+ channels formed by α1B-NC1 (α1B-1, CaV2.2a) (black) pore-forming subunit are distributed diffusely and uniformly in immature neurons, whereas α1B-NC2 (α1B-2, CaV2.2b) (white) is localized in the somatodendritic domain (top). After synaptogenesis (bottom), the α1B-NC1 subunits are clustered at synapses, and the α1B-NC2 subunits remain restricted to soma and dendrites. The association of α1B-NC1 C terminal with Mint1-PDZ1 and CASK-SH3 domains (Maximov et al., 1999) (inset) links synaptic N-type channels to neurexin–neuroligin neuronal adhesion complex (Irie et al., 1997; Nguyen and Sudhof, 1997; Butz et al., 1998; Song et al., 1999) and is likely to play a role in the synaptic clustering of the channels.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation and by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NS39552 (I.B.). We are grateful to Ege Kavalali, Marcus Missler, Thomas Biederer, Gary Banker, and Thomas C. Südhof for helpful discussions, experimental advice, and comments on this manuscript, and to Nan Wang and Phyllis Foley for expert technical and administrative assistance. We thank R. W. Tsien for N-type Ca2+ channel clones, Thomas C. Südhof for Mint1, CASK, and pCMV-HA plasmids and synapsin and PSD-95 antibodies, Boris Shtonda for the CD4-NC construct, Koki Moriyoshi and Ann Marie Craig for mGFP construct, Nikolay Shcheynikov for the help with oocyte expression, and Elena Nosyreva for assistance with experiments.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Ilya Bezprozvanny, Department of Physiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, TX 75390-9040. E-mail:Ilya.Bezprozvanny@UTSouthwestern.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahls FH, Lartius R, Trudeau LE, Doyle RT, Fang Y, Witcher D, Campbell K, Haydon PG. Contact-dependent regulation of N-type calcium channel subunits during synaptogenesis. J Neurobiol. 1998;35:198–208. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199805)35:2<198::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezprozvanny I, Maximov A. Classification of PDZ domains. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:457–462. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezprozvanny I, Scheller RH, Tsien RW. Functional impact of syntaxin on gating of N-type and Q-type calcium channels. Nature. 1995;378:623–626. doi: 10.1038/378623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bichet D, Cornet V, Geib S, Carlier E, Volsen S, Hoshi T, Mori Y, De Waard M. The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the β subunit. Neuron. 2000;25:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biederer T, Sudhof TC. Mints as adaptors. Direct binding to neurexins and recruitment of munc18. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39803–39806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boland LM, Morrill JA, Bean BP. ω-Conotoxin block of N-type calcium channels in frog and rat sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5011–5027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-05011.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borg JP, Straight SW, Kaech SM, de Taddeo-Borg M, Kroon DE, Karnak D, Turner RS, Kim SK, Margolis B. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved heterotrimeric protein complex involved in protein targeting. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31633–31636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borg JP, Lopez-Figueroa MO, de Taddeo-Borg M, Kroon DE, Turner RS, Watson SJ, Margolis B. Molecular analysis of the X11-mLin-2/CASK complex in brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1307–1316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01307.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boudin H, Doan A, Xia J, Shigemoto R, Huganir R, Worley P, Craig AM. Presynaptic clustering of mGluR7a requires the PICK1 PDZ domain binding site. Neuron. 2000;28:485–497. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burack MA, Silverman MA, Banker G. The role of selective transport in neuronal protein sorting. Neuron. 2000;26:465–472. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butz S, Okamoto M, Sudhof TC. A tripartite protein complex with the potential to couple synaptic vesicle exocytosis to cell adhesion in brain. Cell. 1998;94:773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig AM, Banker G. Neuronal polarity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:267–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craven SE, Bredt DS. PDZ proteins organize synaptic signaling pathways. Cell. 1998;93:495–498. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawley JN, Gerfen CR, McKay R, Rogawski MA, Sibley DR, Skolnick P, editors. Current protocols in neuroscience. Wiley; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalgarno DC, Botfield MC, Rickles RJ. SH3 domains and drug design: ligands, structure, and biological function. Biopolymers. 1997;43:383–400. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)43:5<383::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubel SJ, Starr TV, Hell J, Ahlijanian MK, Enyeart JJ, Catterall WA, Snutch TP. Molecular cloning of the α-1 subunit of an ω-conotoxin-sensitive calcium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5058–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellinor PT, Zhang J-F, Horne WA, Tsien RW. Structural determinants of the blockage of N-type calcium channels by a peptide neurotoxin. Nature. 1994;372:272–275. doi: 10.1038/372272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ertel EA, Campbell KP, Harpold MM, Hofmann F, Mori Y, Perez-Reyes E, Schwartz A, Snutch TP, Tanabe T, Birnbaumer L, Tsien RW, Catterall WA. Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron. 2000;25:533–535. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanning AS, Anderson JM. Protein-protein interactions: PDZ domain networks. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1385–1388. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00737-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher CF, Lutz CM, O'Sullivan TN, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Hawkes R, Frankel WN, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Absence epilepsy in tottering mutant mice is associated with calcium channel defects. Cell. 1996;87:607–617. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher TL, Banker GA. The establishment of polarity by hippocampal neurons: the relationship between the stage of a cell's development in situ and its subsequent development in culture. Dev Biol. 1989;136:446–454. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher TL, Cameron P, De Camilli P, Banker G. The distribution of synapsin I and synaptophysin in hippocampal neurons developing in culture. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1617–1626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01617.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goslin K, Asmussen H, Banker G. Rat hippocampal neurons in low density culture. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing nerve cells. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1998. pp. 339–370. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hata Y, Butz S, Sudhof TC. CASK: a novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2488–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02488.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hell JW, Appleyard SM, Yokoyama CT, Warner C, Catterall WA. Differential phosphorylation of two size forms of the N-type calcium channel α1 subunit which have different COOH termini. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7390–7396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibino H, Pironkova R, Onwumere O, Vologodskaia M, Hudspeth AJ, Lesage F. RIM binding proteins (RBPs) couple Rab3-interacting molecules (RIMs) to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2002;34:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00667-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins D, Burack M, Lein P, Banker G. Mechanisms of neuronal polarity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:599–604. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsueh YP, Yang FC, Kharazia V, Naisbitt S, Cohen AR, Weinberg RJ, Sheng M. Direct interaction of CASK/LIN-2 and syndecan heparan sulfate proteoglycan and their overlapping distribution in neuronal synapses. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:139–151. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hullin R, Singer-Lahat D, Freichel M, Biel M, Dascal N, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V. Calcium channel β subunit heterogeneity: functional expression of cloned cDNA from heart, aorta, and brain. EMBO J. 1992;11:885–890. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irie M, Hata Y, Takeuchi M, Ichtchenko K, Toyoda A, Hirao K, Takai Y, Rosahl TW, Sudhof TC. Binding of neuroligins to PSD-95. Science. 1997;277:1511–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DH, Matus AI. Isolation of synaptic plasma membrane from brain by combined flotation-sedimentation density gradient centrifugation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;356:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaneko S, Cooper CB, Nishioka N, Yamasaki H, Suzuki A, Jarvis SE, Akaike A, Satoh M, Zamponi GW. Identification and characterization of novel human Cav2.2 (α1B) calcium channel variants lacking the synaptic protein interaction site. J Neurosci. 2002;22:82–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00082.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kornau HC, Seeburg PH, Kennedy MB. Interaction of ion channels and receptors with PDZ domain proteins. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:368–373. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llinas R, Steinberg IZ, Walton K. Relationship between presynaptic calcium current and postsynaptic potential in squid giant synapse. Biophys J. 1981;33:323–351. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu Q, Dunlap K. Cloning and functional expression of novel N-type Ca2+ channel variants. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34566–34575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matteoli M, Takei K, Perin MS, Sudhof TC, De Camilli P. Exo-endocytotic recycling of synaptic vesicles in developing processes of cultured hippocampal neurons. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:849–861. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.4.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]