Abstract

Background

Adult stem cells are critical for tissue homeostasis; therefore, the mechanisms utilized to maintain an adequate stem cell pool are important for the survival of an individual. In Drosophila, one mechanism utilized to replace lost germline stem cells (GSCs) is dedifferentiation of early progenitor cells. However, the average number of male GSCs decreases with age, suggesting that stem cell replacement may become compromised in older flies.

Methodology/Principal Findings

Using a temperature sensitive allelic combination of Stat92E to control dedifferentiation, we found that germline dedifferentiation is remarkably efficient in older males; somatic cells are also effectively replaced. Surprisingly, although the number of somatic cyst cells also declines with age, the proliferation rate of early somatic cells, including cyst stem cells (CySCs) increases.

Conclusions

These data indicate that defects in spermatogonial dedifferentiation are not likely to contribute significantly to an aging-related decline in GSCs. In addition, our findings highlight differences in the ways GSCs and CySCs age. Strategies to initiate or enhance the ability of endogenous, differentiating progenitor cells to replace lost stem cells could provide a powerful and novel strategy for maintaining tissue homeostasis and an alternative to tissue replacement therapy in older individuals.

Introduction

In regenerative tissues, such as skin and blood, adult stem cells support tissue homeostasis by replenishing cells lost due to normal cellular turnover and/or damage throughout life. Stem cells are found in unique locations within a tissue, known as stem cell niches, which support stem cell self-renewal, maintenance, and survival. Stem cell self-renewal provides a means to maintain a pool of active stem cells; however, in some tissues, the number and/or activity of stem cells declines during aging, suggesting that changes in stem cell behavior likely contribute to reduced tissue homeostasis in older individuals (reviewed in [1]).

In the Drosophila testis, male germline stem cells (GSCs) and cyst stem cells (CySCs) are located at the apical tip where they are in contact with a cluster of somatic cells called the hub (Figure 1A). Hub cells secrete the ligand Unpaired (Upd), which activates the Janus kinase - Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (Jak-STAT) signal transduction pathway within adjacent stem cells to regulate self-renewal, maintenance, and niche occupancy [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. When a GSC divides, one daughter cell remains in contact with the hub and retains stem cell identity, while the other daughter cell is displaced away from the hub and initiates differentiation as a gonialblast (GB). GBs undergo four rounds of mitotic amplification divisions with incomplete cytokinesis to produce a cyst of 16 interconnected spermatogonia (reviewed in [7]). A pair of CySCs encapsulates each GSC, aids in regulating GSC self-renewal, and cyst cells derived from CySCs ensure differentiation of the developing spermatogonia [8], [9], [10]. In addition to the Jak-STAT pathway, number of other factors have been shown to influence stem cell behavior and the relationship between the germ line and the niche in the testis [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Therefore, successful spermatogenesis requires adequate signaling between hub cells, CySCs, and GSCs to coordinate proper functioning of each cell population and tissue homeostasis [4], [9], [10], [20], [21], [22].

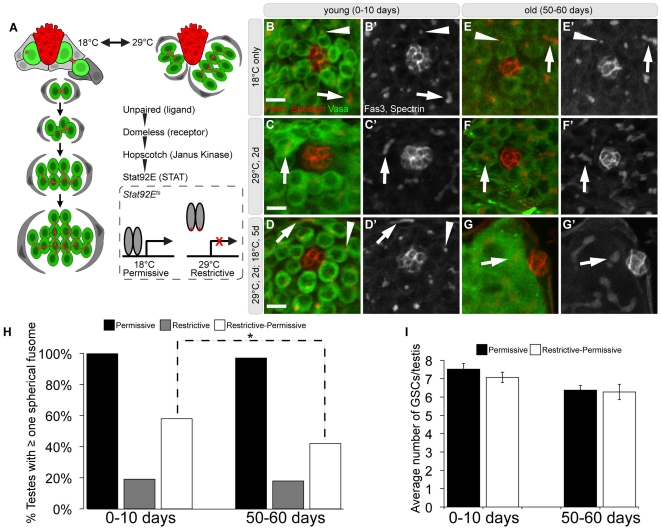

Figure 1. The effect of aging on germ line dedifferentiation in the Drosophila testis.

(A) Schematic of early spermatogenesis and the Stat92Ets reversion paradigm. GSCs (light green) and cyst stem cells (CySCs, light gray) surround the hub (red). A pair of CySCs envelopes each GSC, while cyst cells (dark gray) envelope gonialblasts and spermatogonial cysts (dark green). Red dots and branched structures represent a germ cell-specific organelle called the fusome. Jak-STAT signaling is required for stem cell maintenance. In flies carrying the temperature sensitive allele of Stat92E, GSCs differentiate at the restrictive temperature (29°C). Upon recovery at the permissive temperature (18°C), spermatogonia revert to GSCs. (B–G′) Immunofluorescence images of testes stained for Fasciclin3 (Fas3) (hub; red), alpha-spectrin (fusomes; red), and Vasa (germ cells; green) during dedifferentiation. (B-B′,E-E′) Spectrosomes (arrowheads) within GSCs and branched fusomes (arrows) within spermatogonia at 18°C in young (B-B′) or aged (E-E′) flies. (C-C′,F-F′) Branched fusomes within spermatogonia next to the hub (arrows) in flies shifted to 29°C for 2 days in young (C-C′) or aged (F-F′) flies. (D-D′) Spectrosomes within revertant GSCs (arrowheads) adjacent to the hub in young flies shifted back to 18°C for 5 days. (G-G′) Spermatogonia that contact the hub contain branched fusomes in testes from aged flies shifted back to 18°C for 5 days. (H) Quantification of testes containing at least one spectrosome in young and aged flies at 18°C (Permissive), 29°C (Restrictive), and recovery at 18°C (Restrictive-Permissive). (I) Average number of GSCs in testes that contained GSCs in young and aged flies raised at 18°C and after the recovery at 18°C. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). Bracket with * shows statistically significant changes, p<0.001 Scale bar: 10 µm. Genotype: Stat92EF/Stat92E06346.

The Drosophila germ line has provided an excellent system for investigating the relationship between organismal aging and age-related changes in stem cell behavior [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. Aging results in a decline in spermatogenesis, which can be attributed, at least in part, to a significant decrease in the average number of GSCs that progress through the cell cycle more slowly [25], [28], [30]. Based on the predicted half-life of male GSCs, the testis should be depleted of stem cells by 50 days [28]. However, we have observed a reproducible 35% decrease in the average number of GSCs [25], suggesting that mechanisms must exist to replace lost stem cells over time.

Stem cells could divide symmetrically to replace lost stem cells and maintain full occupancy of the niche, as was demonstrated in Drosophila, where symmetric division of GSCs was observed to replace neighboring GSCs lost to differentiation [31], [32]. In addition, reversion (dedifferentiation) of differentiating germ cells back to a stem cell state has been shown to occur in vivo in the germ line of both Drosophila and mice after depletion of the endogenous stem cell pool [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. Furthermore, using a system to permanently mark differentiating spermatogonia in the Drosophila testis, marked GSCs were found in increasing numbers in response to DNA damage and in aged animals, suggesting that individual stem cells can be replaced by spermatogonia over time [30].

By using a dedifferentiation paradigm in which only germ cell behavior is modified, Sheng et al. demonstrated up to 100% efficiency in dedifferentiation, providing strong evidence that somatic cyst cells play an integral role in the dedifferentiation process [37]. Based on a model where the hub signals to CySCs that then relay self-renewal signals to GSCs [4], [22], efficient coordination and signaling between these three cell types must be required for dedifferentiation to occur. However, aging results in a significant decline in the expression of upd in hub cells [25]. Consequently, decreased Jak-STAT signaling in older males could not only affect stem cell self-renewal, but might also impact dedifferentiation of spermatogonia to replace lost GSCs [25], [37]. Therefore, we have used the Drosophila male germ line to investigate the impact of aging on dedifferentiation and to compare the aging of germline and somatic stem cells residing within the same niche.

Results

Germ cell dedifferentiation occurs in young and old males

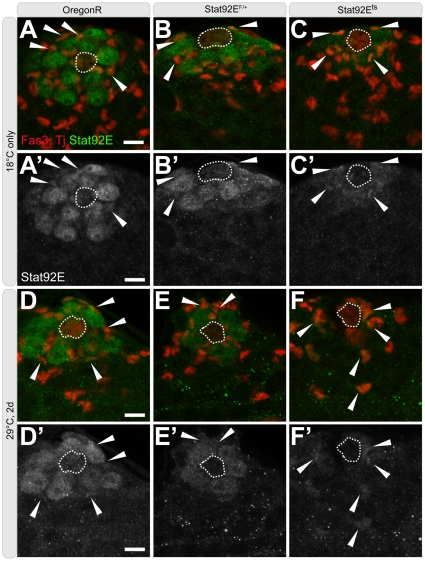

To investigate the impact of aging on dedifferentiation, we used a previously characterized, temperature sensitive allelic combination of Stat92E (Stat92Ets) that permits manipulation of GSC differentiation within the niche (Figure 1A; see Materials and Methods) [34]. Stat92Ets (Stat92EF/Stat92E06346) or out-crossed, control (Stat92EF/+) flies were raised and aged at 18°C post-eclosion (hatching). To initiate dedifferentiation, flies were moved to the restrictive temperature (29°C) for two days, which leads to a decrease in detectable Stat92E protein in germ cells and a loss of GSCs due to differentiation (Figures 1, 2). Subsequently, the flies were shifted back to 18°C for five days and assayed for the ability of spermatogonia to replace lost GSCs.

Figure 2. Stat92E localization in young flies during the reversion paradigm.

(A–F′) Immunofluorescence images of testes from young OregonR, Stat92EF, and Stat92Ets flies stained for hub cells (Fas3, red, outline), early cyst cells (Traffic Jam [TJ], red), and Stat92E (green). (A–C′) at 18°C (D–F′) at 29°C for 2-days. Arrowheads point to Stat92E+TJ+ cells. Scale bars: 10 µm. Genotype: (A-A′,D-D′) OregonR; (B-B′,E-E′) Stat92EF/+; (C-C′) Stat92EF/Stat92E06346; (F-F′) Stat92EF/Stat92EJ6C8.

Germ cell differentiation can be monitored by the morphology of the fusome, a germ cell-specific organelle that is spherical in GSCs and gonialblasts (spectrosome) and becomes progressively branched in spermatogonia during mitotic amplification divisions (Figure 1A). Therefore, to determine the efficiency of dedifferentiation, we quantified the number of testes with at least one spectrosome-containing germ cell at each point during the dedifferentation paradigm. At the permissive temperature (18°C), all testes from young Stat92Ets flies (0–5 days post-eclosion, dpe) contained at least one germ cell with a spectrosome adjacent to the hub (n = 46, Figure 1B-B′,H). When shifted to 29°C for two days, a significant decrease in the number of spectrosome-containing germ cells was observed in testes from Stat92Ets males (19%, n = 42; Figure 1C-C′,H), indicating that GSCs differentiated adjacent to the hub. However, when Stat92Ets flies are shifted back to 18°C, germ cells with spectrosomes were observed in 58% of testes examined (n = 101), verifying that spermatogonia had successfully dedifferentiated into single GSCs (Figure 1D-D′,H).

To determine whether aging affects the ability of spermatogonia to de-differentiate into stem cells, aged Stat92Ets males (50–55 dpe) were exposed to the dedifferentiation paradigm. Raising flies at lower temperatures slows development and delays the onset of aging phenotypes; thus, 50-day old males raised at 18°C resemble 30-day old males raised at 25°C. No difference was observed in the survival of Stat92EF/+ out-crossed controls or Stat92Ets (Stat92EF/06346 or Stat92EF/J6C8) mutant flies that were raised and maintained at 18°C for 50–60 days (data not shown).

In nearly all testes from aged Stat92Ets flies raised and maintained at 18°C, germ cells around the hub contained spectrosomes (97%, n = 55; Figure 1E-E′,H). When aged Stat92Ets flies were shifted to 29°C for 2 days, very few testes had spectrosome-containing germ cells adjacent to the hub (18%, n = 39; Figure 1F-F′,H), similar to the behavior of germ cells in young Stat92Ets males. However, the percentage of testes from aged, Stat92Ets flies with at least one spherical spectrosome was significantly reduced (42%, n = 120) when flies were shifted back to 18°C (Figure 1G-G′,H). This decrease is statistically significant when compared with the number of GSCs in testes from young Stat92Ets flies; however, this likely reflects the overall decrease in GSCs in older males [25], [28]. In testes where successful dedifferentiation had occurred, the average number of GSCs was comparable to that of age-matched controls that had been maintained at 18°C (Figure 1I). Similar results were obtained with another temperature sensitive combination of Stat92E alleles (Figure S1; Materials and Methods). Taken together, our observations indicate that germ cell dedifferentiation appears to be remarkably efficient in both young and aged males.

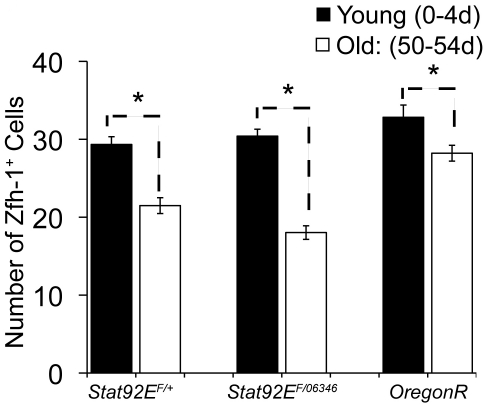

Early cyst cell behavior during aging

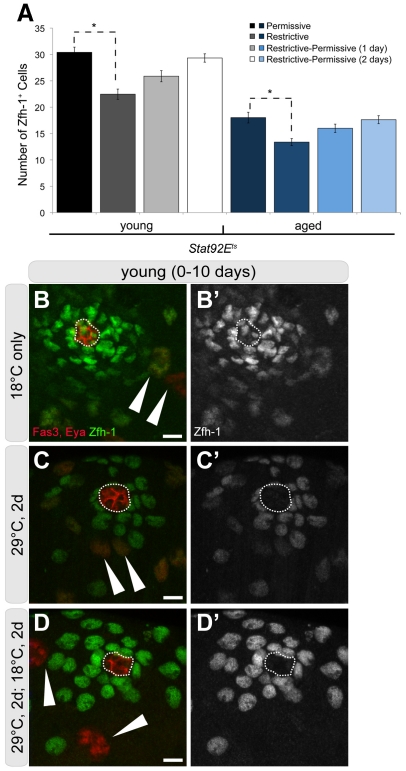

Communication between germ cells and somatic cyst cells is essential not only for regulating GSC proliferation and the normal differentiation of spermatogonia, but it is also required for germline dedifferentiation [37]. Therefore, we wanted to assess the effect of aging on the number and activity of CySCs and early cyst cells, which surround spermatogonia undergoing mitotic amplification divisions. To quantify early cyst cell numbers in young and old flies, we stained for Zfh-1, a transcription factor expressed in cyst cells, including CySCs. The average number of Zfh-1+ cells decreased from 29.3 in testes from young flies to 21.5 in testes from 50-day old control males raised at 18°C (Figure 3; Table 1), consistent with recent results [38]. In Stat92Ets males maintained at 18°C, a similar aging-related decline in the average number of early cyst cells was observed (Figure 3; Table 1).

Figure 3. Decline in early cyst cells during aging.

(A) Graph of the average number of Zfh-1+ cells in young and aged flies maintained at 18°C. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). Genotypes: Stat92EF/+ , Stat92EF/Stat92E06346 and OregonR.

Table 1. Average number of Zfh-1+ cells in testes from young and aged males and during dedifferentiation.

| Average Zfh1+ | 0–10d | 50–60d | |||||||

| Genotype | Temperature | Average | ± | S.E.* | n | Average | ± | S.E. | n |

| F/+ | 18°C only | 29.3 | ± | 0.989978273 | 27 | 21.5 | ± | 1.016403242 | 41 |

| 29°C 2d | 34.5 | ± | 0.975156271 | 33 | 22.3 | ± | 0.673513554 | 44 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 1d | 33.2 | ± | 1.059794061 | 33 | 22.6 | ± | 0.787992222 | 37 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 2d | 27.9 | ± | 0.792849044 | 49 | 21.9 | ± | 0.760115801 | 34 | |

| ± | ± | ||||||||

| F/06346 | 18°C only | 30.4 | ± | 0.88739882 | 37 | 18.0 | ± | 0.870484051 | 39 |

| 29°C 2d | 22.5 | ± | 1.025797512 | 30 | 13.4 | ± | 1.096233896 | 37 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 1d | 25.9 | ± | 1.422814113 | 25 | 16.0 | ± | 1.843554396 | 18 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 2d | 29.3 | ± | 1.229727291 | 54 | 17.6 | ± | 1.47733466 | 19 | |

| ± | ± | ||||||||

| F/J6C8 | 18°C only | 25.7 | ± | 0.87988033 | 43 | 18.5 | ± | 0.928146507 | 30 |

| 29°C 2d | 18.8 | ± | 0.770466843 | 39 | 15.6 | ± | 0.648948915 | 50 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 1d | 21.6 | ± | 0.933421568 | 39 | 16.7 | ± | 1.053799709 | 36 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 2d | 24.4 | ± | 0.757518756 | 54 | 18.5 | ± | 0.88358523 | 42 | |

-Standard Error of the Mean.

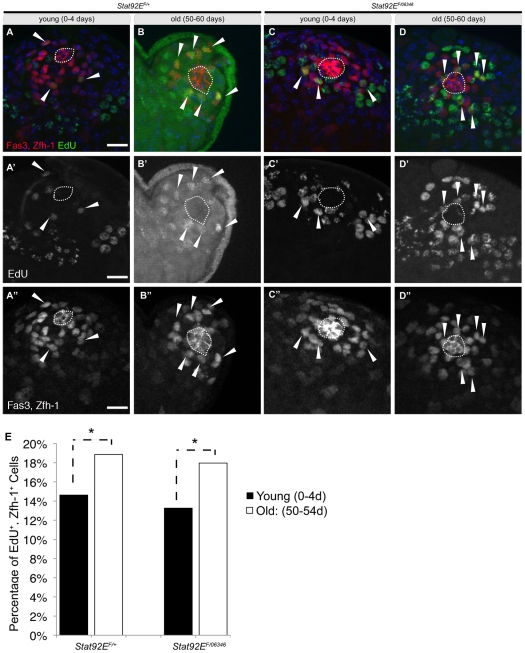

In addition to a decrease in the average number of GSCs with age, we and others observed a decrease in the proliferation rate of GSCs in older flies [25], [30]. Therefore, we also wanted to assay the effect of aging on the activity of CySCs. Although no specific markers for CySCs have been characterized, lineage tracing has placed them adjacent to the hub, intercalated between GSCs [39] where the vast majority of proliferative somatic cells reside [40], [41]. Therefore, quantifying the percentage of early cyst cells that are proliferating provides an indirect read-out for CySC number and activity. The proliferation rate of early cyst cells was determined using ex vivo incorporation of EdU, a thymidine analog, to label cells in S-phase, and the percentage of Zfh-1+ cells that were also EdU+ was calculated (S-phase index). The S-phase index of early cyst cells was 14.6% in testes from young control (Stat92EF/+) males raised at 18°C, which increased to 18.9% when control males were aged for 50 days at 18°C (Figure 4; Table 2). An increase in the S-phase index was also observed in testes from Stat92Ets males from 13.2% in 1-day old flies to 18% in 50-day old flies raised at 18°C (Figure 4; Table 2). Similar results were obtained with another temperature sensitive combination of Stat92E alleles (Figure S1). Therefore, in contrast to the decrease in proliferation observed in GSCs with age, CySCs, as a population, appear to become more active over time.

Figure 4. Increased proliferation of early cyst cells during aging.

(A–D″) Immunofluorescence images of testes from young (A-A″; C-C″) and aged (B-B″; D-D″) flies stained for the hub (Fas3; red, outline), early cyst cells (Zfh-1; red) and labeled with EdU (green). Note EdU+, Zfh-1+ cells (arrowheads). Two merged 1 µm z-slices to represent majority of Zfh-1+ cells. (E) Graph of the percentage of Zfh-1+ cells in S-phase labeled by EdU in young and aged flies. Bracket with * shows statistically significant changes p<0.001. Scale bar: 10 µm. Genotype: Stat92EF/+ and Stat92Ets (Stat92EF/Stat92E06346).

Table 2. S-phase index for cyst stem cells in testes from young and aged males and during dedifferentiation.

| S-phase index | 0–10d | 50–60d | |||

| Genotype | Temperature | S-Phase Index | n | S-Phase Index | n |

| F/+ | 18°C only | 15% | 29 | 19% | 25 |

| 29°C 2d | 11% | 33 | 10% | 44 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 1d | 17% | 33 | 14% | 37 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 2d | 15% | 49 | 20% | 34 | |

| F/06346 | 18°C only | 13% | 24 | 18% | 21 |

| 29°C 2d | 9% | 30 | 13% | 37 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 1d | 13% | 25 | 14% | 18 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 2d | 9% | 54 | 15% | 19 | |

| F/J6C8 | 18°C only | 18% | 23 | 23% | 21 |

| 29°C 2d | 8% | 39 | 10% | 50 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 1d | 14% | 39 | 12% | 36 | |

| 29°C 2d; 18c 2d | 13% | 54 | 15% | 42 | |

Early cyst cell behavior during dedifferentiation

Given the intimate relationship between GSCs and CySCs, we hypothesized that the sustained activity of early cyst cells could play an important role in facilitating spermatogonial dedifferentiation in older animals. Therefore, we wanted to assay the behavior of early cyst stem cells during dedifferentiation in young and aged males. In young Stat92Ets males, the average number of Zfh-1+ cells decreased to 22.5 (Figure 5A; Table 1) at 29°C, demonstrating that cyst cells are sensitive to a decline in Stat92E activity. After a 1-day recovery at 18°C, the number of Zfh-1+ cells increased to 25.9 (n = 25) and was fully restored to 29.3 (n = 54) after just 2 days of recovery at 18°C (Figure 5; Table 1). Interestingly, Stat+ somatic cells were visible, despite the decrease in Stat+ GSCs, indicative of residual Stat92E activity in somatic cells in this genetic background (Figure 2).

Figure 5. Behavior of early cyst cells during dedifferentiation.

(A) Graph of the average number of Zfh-1+ cells throughout the reversion paradigm in young and aged, Stat92Ets flies. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). Bracket with * shows statistically significant changes p<0.001. Genotype: Stat92Ets (Stat92EF/Stat92E06346). (B–D′) Immunofluorescence images of testes from young flies throughout the reversion paradigm stained for the hub (Fas3; red, outline), late cyst cells (Eyes Absent [EyA]; red, arrowhead), and early cyst cells (Zfh-1; green). (B-B′) at 18°C, (C-C′) at 29°C for 2 days, and (D-D′) recovery at 18°C for another 2 days. Number of merged 1 µm z-slices to represent majority of Zfh-1+ cells for (A-A′) z = 4 (B-B′) z = 1 (C-C′) z = 2. Note changes in density of Zfh-1+ cells. Scale bars: 10 µm. Genotype: Stat92EF/Stat92E06346.

Although the average number of Zfh-1+ cells was lower in older Stat92Ets males (Figure 3), a similar trend was observed during the dedifferentiation paradigm. Shifting to 29°C for two days resulted in a drop in Zfh-1+ cells to 13.2 (n = 37); however, the number increased to 16.0 (n = 25) after only one day of recovery, and a complete restoration to 17.6 (n = 19) was observed after 2 days of recovery at 18°C (Figure 5A; Table 1). Similar results were obtained with another temperature sensitive combination of Stat92E alleles (Figure S1), suggesting that early cyst cells are rapidly restored in both young and aged flies under the dedifferentiation paradigm. Importantly, no decrease in the average number of Zfh-1+ cells was detected in young or aged, control (Stat92EF/+) flies shifted to 29°C (Table 1), indicating that high temperature does not affect early cyst cell number.

One explanation for a decrease in Zfh-1+ cells at the non-permissive temperature could be that the cyst cells are differentiating in concert with the germ line. Cyst cells that surround differentiating spermatocytes express the transcription factor Eyes Absent (Eya); however, no Eya+ cells were observed adjacent to the hub in young Stat92Ets males shifted to 29°C for 2 days (Figure 5 B-D′). Therefore, the decrease in Zfh-1+ cells does not appear to be due to direct differentiation into Eya+ cells, which is consistent with previous observations [37].

We next determined the S-phase index of early cyst cells after young Stat92Ets males were allowed to recover for one day at 18°C, prior to complete replacement of Zfh-1+ cells. The S-phase index for early cyst cells in young Stat92Ets males returned to baseline from 9.1% at 29°C (n = 30) to 13.5% upon recovery at 18°C (n = 25) (Table 2). This resumption of proliferation is also observed in young and aged control (Stat92EF/+) males after two days of recovery at 18°C (Table 2). Surprisingly, the S-phase index of early cyst cells in aged Stat92Ets males remained relatively stable at 29°C (13.3%; n = 37) when compared to their activity at 18°C (13.9%; n = 18) (Table 2). Similar results were obtained with another temperature sensitive combination of Stat92E alleles (Table 2).

In conclusion, a decrease in the complement of Zfh-1+ early cyst cells occurs during dedifferentiation in both young and aged males, which is accompanied by a decrease in the S-phase index of early somatic cells. The activity of Zfh-1+ cells quickly returns to baseline when flies are allowed to recover at the permissive temperature, followed subsequently by recovery of early cyst cell numbers. Similar trends are observed in young and aged males; however, the proliferation of early cyst cells, which is higher in aged males (Table 2), appears to remain relatively constant throughout the dedifferentiation paradigm. Maintenance of cyst cell activity is consistent with the presence of Stat+ cyst cells, even at the non-permissive temperature (Figure 2).

Discussion

Several mechanisms have been described that are utilized to replace lost stem cells, including symmetric divisions and dedifferentiation of progenitor cells [31], [32], [33], [34], and studies have indicated that dedifferentiation contributes to replacement of male GSCs throughout life [30]. Here we demonstrate that dedifferentiation remains surprisingly robust in testes from aging flies, despite an overall decrease in GSCs (Figure 1I). Although it is known that the Jak-STAT pathway regulates the process of dedifferentiation in the Drosophila testis, little is known about the mechanisms by which spermatogonia are recruited into the niche and are able to reassume asymmetric, self-renewing divisions [37]. Regardless, it is clear that the somatic cyst cells play an active role in regulating the dedifferentiation process [37].

We have assayed the effects of aging on somatic cells within the Drosophila testis and found that despite an age-related decrease in early cyst cell numbers, those cyst cells that remain are more active as revealed by an increased percentage of early somatic cells that are progressing through S-phase (Figure 4; Tables 1, 2). The increase in cyst cell activity is reminiscent of the behavior of somatic cells in the complete absence of germ cells, as in the case of agametic animals [39], which may reflect a decline in anti-proliferative signals normally emanating from germ cells. Alternatively, the increase in early cyst cell activity with age may represent a mechanism by remaining cyst cells to compensate for the age-related loss of somatic cells.

In addition, we found that somatic cell number and activity recovers rapidly after dedifferentiation, providing a pool of somatic cells to facilitate spermatogonial dedifferentiation (Figure 5, Tables 1 and 2). Given the important role that cyst cells play in facilitating spermatogonial dedifferentiation and the fact that somatic cells appear to remain quite active in older animals (Figure 4, Tables 1 and 2), we propose that this could be one reason dedifferentiation remains robust during aging.

Dedifferentiation is a conserved process that has been long appreciated as a component of regeneration of tissues in amphibians and fish [42]; however, dedifferentiation as a potential mechanism for maintenance or repair of mammalian tissues has not been fully explored. A better understanding of how dedifferentiation of progenitor cells can replace lost or damaged stem cells could provide insight into this process. Future studies that characterize specific stem cell markers and signaling pathways, and the development of technologies that allow long-term in vivo imaging of tissues undergoing regeneration will be critical for understanding the physical interplay between stem and support cells within the context of a shared niche. Furthermore, the mechanisms regulating the reversion of a germ cell to a GSC may shed light on the plasticity of differentiated cell types and their conversion to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) to be used for disease modeling and stem cell-based therapies. Ultimately, strategies to initiate or enhance the ability of endogenous, differentiating progenitor cells to replace lost stem cells could provide a powerful alternative to stem cell transplantation and tissue replacement therapy in older individuals.

Materials and Methods

Fly husbandry and stocks

Flies were raised on standard cornmeal-molasses-agar medium at 18°C unless otherwise indicated. Newly eclosed 0–5 day old male flies were collected in vials containing up to 30 males and 10 females. Vials for aging experiments were supplemented with fresh yeast paste and changed every 7 days.

Three Stat92E mutant alleles were used: temperature sensitive mutant allele Stat92EFrankenstein (Stat92EF) (gift from E. Matunis) [43], the null Stat92E06346 (Bloomington) [44], and Stat92EJ6C8 alleles (gift from N. Perrimon) [45]. The temperature sensitive heteroalleic combinations (‘Stat92Ets’) used were: Stat92EF/Stat92E06346 and Stat92EF/Stat92EJ6C8, and specific genotypes are noted in figure legends. ‘Control’ flies are Stat92EF/+ (Stat92EF out-crossed to wildtype OregonR females). For reversion assays, flies were raised at 18°C, shifted to 29°C for 2 days, shifted back to 18°C and allowed to recover for 5 days before assaying for GSC reversion [34], or for 1 or 2 days for early cyst cell recovery.

Immunofluorescence and Microscopy

Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously [25]. The polyclonal rabbit anti-Vasa (1∶3000, gift from P. Lasko), guinea pig anti-Traffic Jam (1∶3000) (gift from D. Godt), rabbit anti-Stat92E (1∶800)(gift from D. Montell) and guinea pig anti-Zfh1 (1∶3000) (gift from C. Doe) were used at indicated concentrations. Mouse anti-alpha-spectrin (3A9)(1∶10), mouse anti-Fasciclin3 (7G10)(1∶10), and mouse anti-Eya (EYA10H6)(1∶10) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes. Samples were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M or a Zeiss AxioObserver and processed using AxioVision (version 4.8; Carl Zeiss) and Adobe Photoshop software (Mountain View, CA).

Quantification of average number of GSCs and the percentage of testes containing spectrosomes

GSCs are defined as a germ cell (Vasa+) that contacts Fasciclin 3+ hub cells. Only those samples with an easily distinguishable hub within the sizes of 10–18 µm were included in the quantification. Testes were counted as containing a spectrosome when at least one GSC contained a spectrosome marked by anti-alpha-spectrin. A Chi-squared test was performed to evaluate statistical significance. A Student's two-tailed t-test was performed to evaluate statistical significance of GSC counts after dedifferentiation. Above experiments were performed at least 2 times with a total n≥40 testes for percentage of spherical fusomes or n≥30 for average number of GSCs. Standard error of the mean values were calculated for averages.

Ex Vivo EdU incorporation

EdU incorporation was performed and analyzed using the Click-iT® EdU Imaging Kit (Invitrogen), with the following modifications. All procedures were performed at room temperature with minimal exposure to light. Crude dissection of testes was performed in 1× Ringer's buffer and then transferred immediately to 1× Ringer's buffer in a glass embryo dish for no more than 10 minutes. Testes were subsequently transferred to 30 µM EdU diluted in 1× Ringer's buffer for 30′. After incorporation, testes were fixed for 20′ in 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in 1× PBS, followed by two washes with 1× PBST (0.5% Triton-×100) and blocked with 3% BSA in 1× PBS. Testes were bathed in the Click-iT® reaction cocktail for 30 minutes. IF was performed as indicated above.

Quantification of average number of Zfh-1+ early cyst cells and Percentage of EdU+ cells

All Zfh-1+ early cyst cells around the hub were counted, unless they exceeded 30 µm away from the hub. A Student's two-tailed t-test was performed to evaluate statistical significance (p<0.05). An EdU+ cell was assayed as positive when the majority of the cell was labeled and EdU+ co-localized with Zfh-1. The S-phase index was determined as the number of EdU+ cells/Zfh-1+ cell X 100. A Tukey-Kramer HSD test was used to determine statistical significance, (positive value was considered significant). Experiments were performed at least 2 times with a total n≥30 testes, unless otherwise stated in text. Standard error of the mean values were calculated for averages.

Supporting Information

The effect of aging on germ line dedifferentiation in the Drosophila testis. (A) Graph of the percentage of testes containing at least one spectrosome in young and aged flies throughout the reversion paradigm at 18°C (Permissive), 29°C for 2 days (Restrictive), and shift back to 18°C for 5 days (Restrictive-Permissive). (B) Graph of the average number of GSCs before and after the reversion paradigm. Graph of the average number of Zfh-1+ cells throughout the reversion paradigm in young and aged flies. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). (D) Graph of the percentage of Zfh-1+ cells in S-phase labeled by EdU in young and aged flies. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). Bracket with * shows statistically significant changes. p<0.001 Genotype: Stat92EF/Stat92EJ6C8.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to E. Matunis, N. Perrimon, and P. Lasko for their generosity with reagents and fly stocks and to members of the Jones lab for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: National Institutes of Health (www.nih.gov) 5R01 AG028092-04 (Jones, PI), 2T32 HD007495 (C. Kintner, PI). California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (www.cirm.ca.gov) RN1-00544-1 (Jones, PI). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jones DL, Rando TA. Emerging models and paradigms for stem cell ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:506–512. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiger AA, Jones DL, Schulz C, Rogers MB, Fuller MT. Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science. 2001;294:2542–2545. doi: 10.1126/science.1066707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulina N, Matunis E. Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science. 2001;294:2546–2549. doi: 10.1126/science.1066700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Zfh-1 controls somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila testis and nonautonomously influences germline stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issigonis M, Tulina N, de Cuevas M, Brawley C, Sandler L, et al. JAK-STAT signal inhibition regulates competition in the Drosophila testis stem cell niche. Science. 2009;326:153–156. doi: 10.1126/science.1176817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh SR, Zheng Z, Wang H, Oh SW, Chen X, et al. Competitiveness for the niche and mutual dependence of the germline and somatic stem cells in the Drosophila testis are regulated by the JAK/STAT signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:500–510. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita YM, Fuller MT, Jones DL. Signaling in stem cell niches: lessons from the Drosophila germline. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:665–672. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matunis E, Tran J, Gonczy P, Caldwell K, DiNardo S. punt and schnurri regulate a somatically derived signal that restricts proliferation of committed progenitors in the germline. Development. 1997;124:4383–4391. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiger AA, White-Cooper H, Fuller MT. Somatic support cells restrict germline stem cell self-renewal and promote differentiation. Nature. 2000;407:750–754. doi: 10.1038/35037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran J, Brenner TJ, DiNardo S. Somatic control over the germline stem cell lineage during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Nature. 2000;407:754–757. doi: 10.1038/35037613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shivdasani AA, Ingham PW. Regulation of stem cell maintenance and transit amplifying cell proliferation by tgf-beta signaling in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2065–2072. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawase E, Wong MD, Ding BC, Xie T. Gbb/Bmp signaling is essential for maintaining germline stem cells and for repressing bam transcription in the Drosophila testis. Development. 2004;131:1365–1375. doi: 10.1242/dev.01025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherry CM, Matunis EL. Epigenetic regulation of stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila testis via the nucleosome-remodeling factor NURF. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inaba M, Yuan H, Salzmann V, Fuller MT, Yamashita YM. E-cadherin is required for centrosome and spindle orientation in Drosophila male germline stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLeod CJ, Wang L, Wong C, Jones DL. Stem cell dynamics in response to nutrient availability. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2100–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monk AC, Siddall NA, Volk T, Fraser B, Quinn LM, et al. HOW is required for stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila testis and for the onset of transit-amplifying divisions. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:348–360. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monk AC, Siddall NA, Fraser B, McLaughlin EA, Hime GR. Differential roles of HOW in male and female Drosophila germline differentiation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michel M, Raabe I, Kupinski AP, Perez-Palencia R, Bokel C. Local BMP receptor activation at adherens junctions in the Drosophila germline stem cell niche. Nat Commun. 2011;2:415. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, McLeod CJ, Jones DL. Regulation of adult stem cell behavior by nutrient signaling. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2628–2634. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.16.17059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar A, Parikh N, Hearn SA, Fuller MT, Tazuke SI, et al. Antagonistic roles of Rac and Rho in organizing the germ cell microenvironment. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1253–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz C, Wood CG, Jones DL, Tazuke SI, Fuller MT. Signaling from germ cells mediated by the rhomboid homolog stet organizes encapsulation by somatic support cells. Development. 2002;129:4523–4534. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Germline self-renewal requires cyst stem cells and stat regulates niche adhesion in Drosophila testes. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:806–811. doi: 10.1038/ncb2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis J, Spradling A. Identification and behavior of epithelial stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1995;121:3797–3807. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan L, Chen S, Weng C, Call G, Zhu D, et al. Stem cell aging is controlled both intrinsically and extrinsically in the Drosophila ovary. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle M, Wong C, Rocha M, Jones DL. Decline in self-renewal factors contributes to aging of the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaczmarczyk AN, Kopp A. Germline stem cell maintenance as a proximate mechanism of life-history trade-offs? Drosophila selected for prolonged fecundity have a slower rate of germline stem cell loss. Bioessays. 2011;33:5–12. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mair W, McLeod CJ, Wang L, Jones DL. Dietary restriction enhances germline stem cell maintenance. Aging Cell. 2010;9:916–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallenfang MR, Nayak R, DiNardo S. Dynamics of the male germline stem cell population during aging of Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2006;5:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Jones DL. The effects of aging on stem cell behavior in Drosophila. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng J, Turkel N, Hemati N, Fuller MT, Hunt AJ, et al. Centrosome misorientation reduces stem cell division during ageing. Nature. 2008;456:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature07386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie T, Spradling AC. A niche maintaining germ line stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Science. 2000;290:328–330. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheng XR, Matunis E. Live imaging of the Drosophila spermatogonial stem cell niche reveals novel mechanisms regulating germline stem cell output. Development. 2011;138:3367–3376. doi: 10.1242/dev.065797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kai T, Spradling A. Differentiating germ cells can revert into functional stem cells in Drosophila melanogaster ovaries. Nature. 2004;428:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature02436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brawley C, Matunis E. Regeneration of male germline stem cells by spermatogonial dedifferentiation in vivo. Science. 2004;304:1331–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.1097676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barroca V, Lassalle B, Coureuil M, Louis JP, Le Page F, et al. Mouse differentiating spermatogonia can generate germinal stem cells in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:190–196. doi: 10.1038/ncb1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakagawa T, Sharma M, Nabeshima Y, Braun RE, Yoshida S. Functional hierarchy and reversibility within the murine spermatogenic stem cell compartment. Science. 2010;328:62–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1182868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheng XR, Brawley CM, Matunis EL. Dedifferentiating spermatogonia outcompete somatic stem cells for niche occupancy in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inaba M, Yuan H, Yamashita YM. String (Cdc25) regulates stem cell maintenance, proliferation and aging in Drosophila testis. Development. 2011;138:5079–5086. doi: 10.1242/dev.072579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonczy P, DiNardo S. The germ line regulates somatic cyst cell proliferation and fate during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development. 1996;122:2437–2447. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voog J, D'Alterio C, Jones DL. Multipotent somatic stem cells contribute to the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Nature. 2008;454:1132–1136. doi: 10.1038/nature07173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng J, Tiyaboonchai A, Yamashita YM, Hunt AJ. Asymmetric division of cyst stem cells in Drosophila testis is ensured by anaphase spindle repositioning. Development. 2011;138:831–837. doi: 10.1242/dev.057901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Straube WL, Tanaka EM. Reversibility of the differentiated state: regeneration in amphibians. Artif Organs. 2006;30:743–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baksa K, Parke T, Dobens LL, Dearolf CR. The Drosophila STAT protein, stat92E, regulates follicle cell differentiation during oogenesis. Dev Biol. 2002;243:166–175. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hou XS, Melnick MB, Perrimon N. Marelle acts downstream of the Drosophila HOP/JAK kinase and encodes a protein similar to the mammalian STATs. Cell. 1996;84:411–419. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spradling AC, Stern D, Beaton A, Rhem EJ, Laverty T, et al. The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project gene disruption project: Single P-element insertions mutating 25% of vital Drosophila genes. Genetics. 1999;153:135–177. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The effect of aging on germ line dedifferentiation in the Drosophila testis. (A) Graph of the percentage of testes containing at least one spectrosome in young and aged flies throughout the reversion paradigm at 18°C (Permissive), 29°C for 2 days (Restrictive), and shift back to 18°C for 5 days (Restrictive-Permissive). (B) Graph of the average number of GSCs before and after the reversion paradigm. Graph of the average number of Zfh-1+ cells throughout the reversion paradigm in young and aged flies. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). (D) Graph of the percentage of Zfh-1+ cells in S-phase labeled by EdU in young and aged flies. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE). Bracket with * shows statistically significant changes. p<0.001 Genotype: Stat92EF/Stat92EJ6C8.

(TIF)