Abstract

Increasingly, there has been an interest in the association between epilepsy and autism. The high frequency of autism in some of the early-onset developmental encephalopathic epilepsies is frequently cited as evidence of the relationship between autism and epilepsy. While these specific forms of epilepsy carry a higher than expected risk of autism, most if not all of the association may be due to intellectual disability (ID). The high prevalence of interictal EEG discharges in children with autism is also cited as further evidence although errors in the diagnosis of epilepsy seem to account for at least part of those findings. The prevalence of ID is substantially elevated in children with either epilepsy or autism. In the absence of ID, there is little evidence of a substantial, if any, increased risk of autism in children with epilepsy. Further, although the reported prevalence of autism has increased over the last several years, much of this increase may be attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, conceptualization of autism in the presence of ID, and laws requiring provision of services for children with autism. In the context of these temporal trends, any further efforts to tease apart the relationships between epilepsy, ID, and autism will have to address head-on the accuracy of diagnosis of all three conditions before we can determine whether there is indeed a special relationship between autism and epilepsy.

The co-occurrence of epilepsy with autism spectrum disorders (ASD or autism) has been the subject of frequent reviews [1-6]. This has understandably led to speculation that there are common mechanisms linking the two types of disorders. Indeed, some epilepsy syndromes and specific genetic factors involved in those syndromes are associated with a high risk of ASD. For example, patients with tuberous sclerosis, particularly when associated with TSC2 mutations [7,8] Dravet syndrome, usually caused by mutations in the voltage- gated neuronal sodium channel gene SCN1A[ 9], and epilepsy in females with mental retardation or EFMR, found to be secondary to PCDH19 mutations [10] tend to have very high occurrence of autistic like features if not autism proper. As Brooks-Kayal points out, these and other genetic factors are implicated in specific early-onset epileptic encephalopathies and the mechanisms involved in producing the epilepsy might play a role in producing autistic features [1]. While this possibility needs investigation, an obvious factor linking epilepsy and autism, intellectual disability (ID), must first be carefully considered. The role of ID is potent and could potentially explain most if not all of the association between epilepsy and autism. This is not a new concept [3, 4, 11]; however, in the context of the increasing use of genomic technology and other methods for exploring causation and mechanisms, and capability to mount complex, large scale investigations as well as the changing definitions and understanding of autism, the role of ID in the association between epilepsy and autism must be thoroughly accounted for.

To appreciate the complexity of the epilepsy-autism-ID triad, one must first understand what autism is, how it has been defined and diagnosed over time. In this context, we examine the relationships between autism and intellectual impairment, epilepsy and intellectual impairment, autism and epilepsy, and the implications for the three together. This review does not cover causes of autism per se which are covered in detail by others elsewhere, for example, Hughes (2009) [12] . As much as possible, we focus on data from population-based studies and regional centers to ensure the findings are robust and representative of affected individuals in the general population.

Features and diagnosis of autism and changes over time

Autism is a developmental disorder characterized by a specific pattern of persistent deficits in social reciprocity, communication, and fixed interests, and repetitive behaviors. These fundamental features are conceptualized similarly in all diagnostic frameworks, such as DSM-IV-TR , ICD-10 and the proposed DSM-5 [13]. Although the cardinal features used in diagnosing autism have remained relatively stable over time, there has been a broadening in the concept of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) to include milder forms of autism, particularly Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorders not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) and to recognize autism in the context of intellectual impairment. The proposed DSM-V could result in yet further changes in autism diagnosis as these separate diagnostic categories will be merged into a single entity, “autistic spectrum disorder.”

Ideally, the clinical diagnosis of autism should be reached by conducting an observation and patient examination, and obtaining information from multiple sources such as parents and teachers. It requires the presence of full diagnostic criteria and differentiation from typical development, language delay, and other “non-spectrum” psychiatric disorders (DSM-V). To this day, no diagnostic biological markers or specific tests for ASD are available, thus diagnosis depends on the individual clinician’s interpretation of diagnostic criteria, which can be affected by multiple factors, most notably level of training and clinical expertise, and conceptualization of ASD [14]. Generally, autism cannot be confidently diagnosed before the age of about 36 months although early detection of at least some forms is possible [15].

Studies published in the last ten years, report a prevalence of autism in the population on the order of 6 to 11/1000 [16-19]; however there is some evidence that the prevalence may have increased over the last 30 or more years [16, 20, 21], and estimates within the US find rates rising recently even during the early to mid 2000s [22, 23]. Many factors can influence these figures including the availability of resources to treat and manage children with ASD. Palmer et al. found that the prevalence of ASD diagnoses in the school system was directly tied to the wealth of the community with lower prevalences found in poorer communities [24]. Definitions are important as well. A general population study from the UK [19] reported an overall prevalence of 116.1/10,000 which dropped to 24.8/10,000 when narrow definition and more rigorous criteria were employed. Within a single population, strikingly different estimates of prevalence were obtained in two consecutive birth cohorts. Autism in the first cohort, born in 1974-1983, was diagnosed based on ICD-9 criteria with a resulting prevalence of 3.8/10,000. In the second cohort (born in 1984-1993), ICD-10 criteria with the addition of some other criteria were used with a resulting prevalence of 8.6/10,000. The diagnosis of Asperger syndrome was explicitly excluded in both cohorts [25]. One could argue for changes in the underlying prevalence over time; however, a separate research group in a single region measured the prevalence of autism during two consecutive time periods using the same methods and criteria and found highly consistent estimates across the two periods [17, 26]. Both ID and epilepsy occur in comparably small proportions of the population. As part of its definition, ID may generally be considered when IQ drops below 70 (2 standard deviations below the mean) which statistically should occur in roughly 2% of the population. This is likely an overestimate as criteria for functional impairment must also be met [13]. Over the course of childhood and early adolescence, the cumulative risk of developing epilepsy is approximately 6-7/1000 [27].

Key to the discussion of autism and epilepsy, the diagnosis of autism requires that the autistic features cannot be fully explained by developmental delays or related impairments. They must also be present since early childhood, although some may not become fully apparent until later when social expectations for an older child result in the deficits becoming evident. The last point is more strongly emphasized in the recent revisions to the DSM [28] and is crucial because the strong association and overlapping symptomatology between autism and ID can lead to both the over- and under-diagnosis of autism. Deficits in communication and social skills due to cognitive delay and repetitive self-stimulatory behaviors are frequently observed in ID patients without necessarily constituting the basis for diagnosing autism. This has been emphasized in the autism screening literature. For example, in toddlers born very prematurely (<28 weeks), the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (mCHAT) scores were strongly correlated with motor and sensory impairments. Of those with vision impairments or hearing impairments, 71% scored positive on the mCHAT autism screen versus 20-21% without such impairments. Cerebral palsy was strongly associated with positive autism screening results including 76% of children with quadreparesis, 30% with diparesis, and 44% of those with hemiparesis. This is in contrast to 22% screening positive in the absence of cerebral palsy [29]. A population-based study found a 40% false positive rate for an autism screening program with intellectual disabilities, language disorders, and specific behavioral disorders being common reasons for the error [30]. A preliminary report from a tertiary epilepsy center found that 16/44 children screened positive for autism with the mCHAT. All 16 also had developmental delays, and in 12, the neurological and developmental impairments were found to explain the positive autism screening results [31].

The potential errors in the over-interpretation of autistic symptoms and use of the diagnosis of autism in individuals with ID was highlighted by Sevin et al [32]. They assessed the initial (at admission) prevalence of DSM-IV based psychiatric diagnoses and longitudinal outcome in 150 adolescents (aged 11 to 19 years) with ID admitted to an inpatient psychiatric specialty unit. After 15 months, PDD was identified in 8.6% of sample whereas the initial prevalence had been 16.0%, an almost halving in the prevalence of PDD in just over a year. Considering the persistent course of ASD symptoms and unlikely resolution of ASD over 15 months of treatment in adolescence, these data likely reflect diagnostic disagreement between clinicians or an over interpretation of transient autistic symptoms which may be temporary due to emerging medical or neurological disorders. When developmental difficulties improve over time and the child is able to communicate more effectively and negotiate social situations, the autistic symptoms may weaken and previously diagnosed ASD resolve. This is not true in primary autism, where impairment persists. Consequently, one must be concerned about the over-interpretation of autistic features in individuals with ID, especially if assessed at only one point in time.

Diagnoses of autism can also be missed in people with intellectual disabilities. Saemundsen reported a 21% prevalence of autism in adults (18-87 years old) with intellectual disability [33]. Only 11 of the 25 cases of autism identified had been previously diagnosed as having autism, all during childhood. The other 14 cases with autism were found by the investigators through screening and diagnostic procedures. Possibly individuals whose diagnoses of autism were missed during childhood were older patients who were children during a time when the concepts surrounding autism were somewhat different and many considered that intellectual disability excluded the diagnosis [34]. Once in an adult care setting, the diagnosis was likely never revisited. La Malfa et al. reported similar observations with an initial ASD prevalence of 7.8% rising to 39.2% with more thorough investigation of a single group of intellectually disabled adults patients [35].

There is currently a lack of consensus regarding how best to conceptualize autism with and without ID [36] as none of the existing psychiatric diagnostic criteria have been specifically developed for use in people with ID [37 32]. This is reflected in the different yields of standardized screening and diagnostic instruments. For example, De Bildt et al. applied several autism screening and diagnostic instruments to the same group of individuals with intellectual disability [38]. Although two different screening instruments identified similar proportions of subjects as having autism (18.4% for the Scale of Pervasive Developmental Disorders in Mentally Retarded Persons or PDD-MRS and 17.2% for the Autism Behavior Checklist or ABC), only 7.8% were identified with autism according to both instruments.

An additional source for the increase in the prevalence of autism may be the special education laws in the US and elsewhere that require special educational assistance for children with autism [36, 39, 40] . These concerns see some validation in the striking increase in children receiving special educational services for autism in the United States from 1992 through 2008. This increase was reported starting in the early 1990s in different states [41-43] and followed the signing into law of the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act which specifically identified autism as a disorder that entitled a child to special education services [44]. Similar phenomena have been observed in Australia [45] and Israel, [46] and investigators have suggested that changes in diagnostic criteria as well as qualifying for services and greater availability of services were likely factors in the increase. In this context, the evolution in the understanding of autism over time and the consequences for diagnostic practices has likely contributed to several trends. These include a shift from the narrow definition of classical autism with severe functional impairment to a broader range of expression for autistic symptoms with less severe functional impairment on the one hand as well as inclusion of those with more severe intellectual impairment on the other [30].

Related to these trends, there is evidence that diagnostic substitution (i.e., using the ASD diagnosis instead of another diagnosis), may occur [21, 39, 40]. Shattuck reported an increasing administrative prevalence of autism to be significantly associated with corresponding declines in the prevalence of mental retardation and learning disabilities. From 1994 to 2003, the average prevalence of autism (based on administrative data) increased from 0.6 to 3.1 per 1000 [39]. During the same period, the prevalence of mental retardation and learning disabilities declined by 2.8 and 8.3 per 1000, respectively. He suggested that declines in ID prevalence may have been offset by the increase in autism prevalence. King and Bearman [21] estimated that, in California, about a quarter of the increased case load of autism from 1992 to 2005 was due solely to changes in diagnostic practices, substitution in particular.

Another concern with diagnoses, especially when used for educational purposes, is diagnosis “augmentation,” application of the diagnosis to children with autistic features who do not truly meet diagnostic criteria for autism as described above in order to enable a child to receive necessary educational services [36, 47]. While understandable from a patient advocacy perspective, this hampers research investigations as these individuals do not meet rigorous diagnostic criteria, and many do not have autism by such standards.

Autism and Intellectual Disability

Despite the temporal trends and differences in application of diagnostic criteria and the concept of autism itself, virtually all studies find a higher prevalence of autism in individuals with intellectual disability than in those whose intellectual function is within the normal range. Studies have examined the prevalence of autism in relation to intellectual disability both by looking at the prevalence of intellectual disability in series of people with autism and conversely the prevalence of autism in people with ID.

In large-scale studies of children with autism, half or more are reported to have some degree of intellectual disability (consistent with IQ<70). Steffenburg and Gillberg’s found that 88% of children with infantile autism or autistic-like conditions (the terms used then) had an IQ<70 with 58% having IQ<50. In more recent studies, this has lessened somewhat [48]. For example, Nichols et al. reported that 60.4% of 8 year-olds meeting their criteria for autism had an IQ score <70 placing them in the intellectual disability range [18]. In the Special Needs and Autism Project series, 55% of children identified as having autism had an intellectual disability, again defined as IQ<70 [49]. The definitions used are important. A population-based study in Brick Township, NJ, considered all children 3 to 10 years of age. Of those with autism spectrum disorder, 49% had IQ scores <70; however, if only those who met strict criteria for autism were considered along with those too impaired to be tested, this figure rose to 63% [16]. A single surveillance network found varying degrees of overlap between autism and epilepsy across different states within the US [22]. In children with ASD, ID was present in anywhere from 29% to 51%.

One would expect the association between autism and ID to depend heavily on the definition of autism, specifically whether it includes Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS. In one British study, 69% of children meeting criteria for autism had some degree of intellectual disability in contrast to 7.6% of those with PDD-NOS and none of the children with Asperger [26]. These latter two categories constituted about two-thirds (65/91) of the children identified with an autism spectrum disorder in that study and support Bryson and Smith’s conclusion that most people with autism, broadly defined, do not have intellectual disability [50].

When considered from the perspective of intellectual disability, the prevalence of autism increases with the severity of the ID. De Bildt et al. specifically examined individuals with known intellectual disability. Depending on the diagnostic criteria and instruments used, they found a four to ten-fold increase in prevalence of ASD in people with mild to severe/profound mental retardation [38]. For example, using the PDD-MRS, the prevalence of autism was 2% for people with mild MR rising to 28.2% for severe-profound MR. Very similar trends, although somewhat higher absolute values, were reported by an Italian group [35]. For adults with mild, moderate, severe, and profound ID, the prevalence of autism was 8.3%, 24.1%, 37.1% and 59.6% respectively.

The other feature in the population that is strongly associated with autism is male gender with virtually every study demonstrating a 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence in males than in females [16-19, 25, 26, 41, 46, 48]. Current theories about the “male brain” as well as assortative mating and delayed age at parenthood have been proposed [51]. Notably, this association diminishes and, in some studies even disappears in individuals with intellectual disability [18, 49]. A general impression from a review of the epidemiology of autism concluded that the sex ratio depended on the presence of intellectual disability and dropped to about 2 in those with ID [52]. This pattern suggests that autism in association with intellectual impairment may be a different phenomenon from autism in someone of normal intellect. The diagnostic issues discussed above need to be considered as well as there may be a surfeit of autism diagnoses due to autistic features associated with ID (in both boys and girls) which are over interpreted as autism and thus obscure any gender difference.

Epilepsy and Intellectual Disability

Epilepsy is recognized as a large group of disorders which, although characterized by the occurrence of epileptic seizures, are also strongly associated with a range of behavioral and cognitive comorbidities [53]. Intellectual disability per se is very common in children with epilepsy. Four population-based or population-representative studies reported that approximately a quarter (20-27%) of children with epilepsy also had some degree of intellectual disability [54-57]. The prevalence is highest in children with the youngest age at onset of epilepsy and in association with structural brain lesions. ID is especially high in a group of epilepsy syndromes often referred to collectively as the epileptic encephalopathies because of their strong association with developmental and behavioral disabilities [56, 58]. These syndromes include several disorders such as (but not limited to) West syndrome, Dravet, Ohtahara, and Lennox-Gastaut syndromes. Developmental and cognitive outcomes in these syndromes are rarely within the normal range [9, 55, 56]. Increasingly, investigations are targeting underlying genetic factors involved in intellectual disability syndromes closely associated with epilepsy [59]. In general, however, and apparently regardless of underlying cause, younger age at onset of epilepsy, particularly when drug-resistant, appears to place a child at substantially increased risk of intellectual impairment although autistic features and the diagnosis of autism per se are not always described [60, 61]. It is in the children with the youngest age at onset of seizures that one would expect to see the highest levels of autism because of their increased burden of intellectual disability and also because this is the age when autism begins to manifest itself.

Autism and Epilepsy

Many investigators have approached the issue of epilepsy and autism from the vantage point of the latter. In people with autism, estimates range from a few to as much as a quarter also having epilepsy [4]. In a prevalent sample of 286 children with autism evaluated at a tertiary center specializing in both autism and epilepsy, in children diagnosed with autism, the prevalence of epilepsy was 7% among those with no motor deficits or severe intellectual disability [62]. By contrast the prevalence of epilepsy was as high as 42% in those with motor deficits and severe ID. Figures for children with clearly “normal” intellect were not provided, however. In a population-register study, a quarter of individuals diagnosed with infantile autism also had epilepsy in contrast to 1.5% of population-based controlled [63]. With the exception of cerebral palsy, other neurological disorders did not occur more often in the autism group than in controls. The prevalence of epilepsy was greater in association with severity of intellectual impairment; 34% of children with autism and severe intellectual disability (IQ<50) had epilepsy as compared to 27% of those with moderate ID (IQ 50-69) and 9% of those with IQ>=70. In both of these last studies, males out-numbered females overall by about 3:1; however, gender was not clearly associated with being diagnosed with epilepsy. This is largely because, at the most severe end of the intellectual disability spectrum, where the risks of developing epilepsy and of autism are highest, and the gender differential for autism is diminished.

Using patient data from a regional disabilities center, Wong et al. (1993) found that only 11 of 145 (7.6%) children diagnosed with infantile autism were also diagnosed with epilepsy [64]. Of the 11, only one was of normal intellect. Another study from a regional center reported epilepsy in 72 patients with autism [65]. Epilepsy occurred in 15% of the group with IQ<55, 55% of those with “secondary” autism (i.e. with other underlying neurological conditions) but in only 3% (1/34) of those with “primary” autism and IQ>55. Their conclusion was that epilepsy was not a common occurrence in primary autism [65]. In a novel approach to question of epilepsy and autism, Mouridsen et al. looked at the prevalence of epilepsy in parents of children with infantile autism and in parents of controls (children without autism) [66]. The rationale behind the design being that, if epilepsy and autism share genetic mechanisms, then family members of probands with one disorder should be at increased risk for the other disorder. While this is a somewhat novel approach, it has been used in other settings, for example, nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy and sleep disorders [67]. No evidence of a greater prevalence of epilepsy or other neurological disorders was found in case parents compared to control parents.

Of note, while the diagnosis of autism in these studies was often very sophisticated, that for epilepsy was typically based upon the observation of aberrant, episodic behaviors combined with an abnormal scalp EEG. Since then, studies using video-EEG monitoring have demonstrated that children with autism who are evaluated for epilepsy because of events of concern often have epileptiform abnormalities; however, their clinical events are not associated with electrographic evidence of seizure activity [68-70]. There is another substantial literature on the relationship between epileptiform discharges and ASD, autistic regression, and language disorders in the absence of epileptic seizures. Epilepsy is not, however, diagnosed solely on the basis of interictal findings. There are many comparisons made with Landau-Kleffner syndrome, a severe encephalopathy characterized by language impairment and electrographic status epilepticus in sleep, although seizures may not even occur [2,4]. This is a relatively rare disorder, however, and it is not necessarily the best model for studying autism and epilepsy.

Viewed from the other perspective, there are several small series reporting the occurrence of autism in patients with selected types of epilepsy that are strongly associated with autism and autistic features. For example, in a population-based study of seizures with onset in the first year of life, 35% of children with infantile spasms developed autism versus 9% with other forms of epilepsy [71]. Most of the association between spasms and autism was due to the underlying structural lesions associated with the spasms themselves. A separate study reported infantile spasms, relative to all other forms of childhood epilepsy and regardless of age at onset, to be a strong correlate of autism [72]. In patients seen at a tuberous sclerosis clinic, autism was reportedly more likely to occur in patients whose mutation was in theTSC2 gene than in TSC1. Mutations in TSC2 were also more likely to be associated with infantile spasms so the relative importance of the spasms phenotype versus the TSC genotype was not clear [7, 8]. Animal models, however, have also implicated TSC2 mutations as being particularly important in both severe epilepsy and autism [73, 74]. A high prevalence of autistic features although not necessarily classical autism per se is also reported in association with Dravet syndrome [9, 75, 76] and in Epilepsy in Females with Mental Retardation [10]. Finally, in a tertiary clinic, children with established epilepsy were screened for autism and 32% screened positive for autism although cognitive status was not specifically described. Only 9 of 31 with positive screening results had been previously diagnosed with autism. Diagnostic results for the other 22 were not reported [77].

Epilepsy-Autism-ID

While repeated studies report a high prevalence of autism in children with epilepsy and of epilepsy in children with autism, these studies, virtually always also point to the importance of intellectual disability (however labeled) as being the connection between autism and epilepsy. Definitional issues aside, individuals with autism who have ID are at substantially higher risk of epilepsy than are those with relatively normal intellectual function. This general pattern is seen across multiple studies and was the focus and conclusion of an extensive meta-analysis [11]. The complement is true as well. Children with epilepsy and ID are at substantially increased risk of autism relative to those with epilepsy who are of normal intellect [72]. To our knowledge, only two large prospective cohort studies have examined autism in representative series of children with epilepsy [57, 72]. The first reported that 3.9% of a representative cohort of children with epilepsy developed autism but did not provide any breakdowns by level of cognitive function. The second found that 5% of all children in the cohort met criteria for autism; however, only 2% of those with IQ≥80 met criteria. These had almost exclusively Asperger syndrome and involved a range of different epilepsy syndromes. While this estimate is higher than population-based estimates of ASD, all of the concerns regarding diagnostic criteria, substitution and augmentation must be considered. In the end, these findings do not suggest a large additional burden of autism in otherwise cognitively normal children with epilepsy.

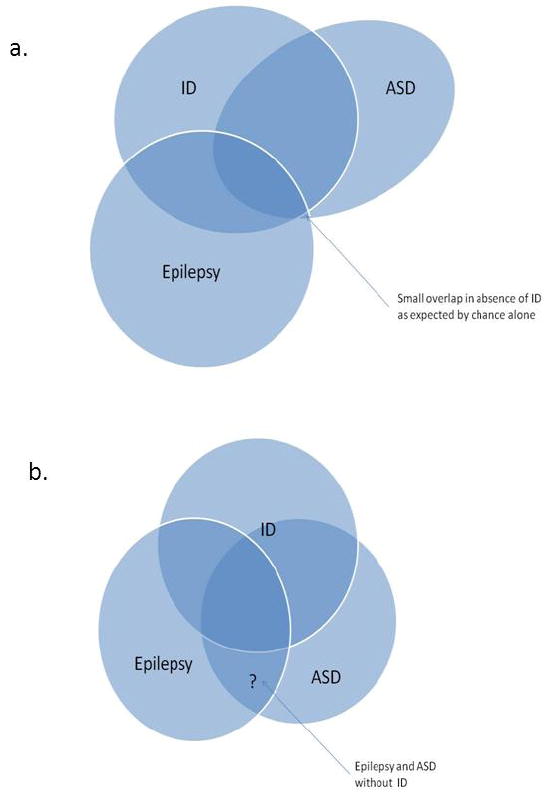

Together, the many studies reviewed above have taken complementary approaches to the epilepsy-autism-ID puzzle and have provided different pieces of information that help resolve this question, although not entirely. Collectively, the literature provides clear evidence that intellectual disability is the main and possibly the only reason that studies find a higher than expected level of autism in children with epilepsy. The changing concept of autism and other factors affecting how the diagnosis is used complicate any investigations into these issues. In the context of US Federal spending on the genetics of autism having neared 1 billion dollars in the last decade [78], and given that advances that have been made in the genetics of ID syndrome [79] as well as specific epilepsy syndromes [80], it is imperative that any further investigations, especially of epilepsy and autism, consider the role of ID. Given how sensitive the yield of ASD diagnoses can be to the methods for ascertaining and diagnosing ASD, any future studies that wish to advance our knowledge of this field will need to have clinically meaningful, standardized approaches for accurately diagnosing autism, epilepsy and intellectual disability in a large enough sample or using a clever enough design so that the role of intellectual disability can be teased apart from the role of epilepsy and its underlying causes. This will allow us to determine the extent to which any association between autism and epilepsy is solely a function of ID (Figure 1a). Only then can we seriously entertain the other possibility, that, above and beyond any contribution from ID, autism and epilepsy truly have a special relationship (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Two hypotheses: (a) Intellectual disability is independently co-morbid with autism and with epilepsy thus inducing an apparent association (large overlap) between the latter two. Absent ID, the overlap between epilepsy and autism in the absence of intellectual disability is no greater than expected by chance alone. (b) Independent associations between epilepsy and ID, ASD and ID; ASD and epilepsy with some having all three disorders. The question on hand is whether the area indicated by the question mark (epilepsy with ASD in the absence if ID) occurs at a greater frequency than expected based on the prevalence of ASD in the general population without either ID and epilepsy and based on the prevalence of epilepsy in the population without either ID and ASD.

Highlights.

Epilepsy and autism are correlated due to a shared association with intellectual disability.

No evidence currently supports an independent association between epilepsy and autism.

Changing diagnostic practices and legislative mandates complicate study of this issue.

Accuracy of autism, ID and epilepsy diagnoses presents challenges to progress in this area.

Acknowledgments

Funding: ATB was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R37-NS31146

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brooks-Kayal A. Epilepsy and autism spectrum disorders: are there common developmental mechanisms? Brain Dev. 2010;32(9):731–8. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besag FM. The relationship between epilepsy and autism: a continuing debate. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(4):618–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levisohn PM. The autism-epilepsy connection. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 9):33–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spence SJ, Schneider MT. The role of epilepsy and epileptiform EEGs in autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:599–606. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000352115.41382.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuchman R, Alessandri M, Cuccaro M. Autism spectrum disorders and epilepsy: moving towards a comprehensive approach to treatment. Brain Dev. 2010;32(9):719–30. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deonna T, Roulet E. Autistic spectrum disorder: evaluating a possible contributing or causal role of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(Suppl 2):79–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Numis AL, Major P, Montenegro MA, Muzykewicz DA, Pulsifer MB, Thiele EA. Identification of risk factors for autism spectrum disorders in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2011;76:981–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182104347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu-Shore CJ, Major P, Camposano S, Muzykewicz D, Thiele EA. The natural history of epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1236–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catarino CB, Liu JYW, Liagkouras I, et al. Dravet syndrome as epileptic encephalopathy: evidence from long-term course and neuropathology. Brain. 2011;134:2982–3010. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheffer IE, Turner SJ, Dibbens LM, et al. Epilepsy and mental retardation limited to females: an under-recognized disorder. Brain. 2008;131:918–27. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amiet C, Gourfinkel-An I, Bouzamondo A, et al. Epilepsy in autism is associated with intellectual disability and gender: evidence from a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:577–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes JR. Update on autism: a review of 1300 reports published in 2008. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2009;16:569–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DSM-5: the future of psychiatric diagnosis. 2010 (Accessed at http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx.)

- 14.Mahoney WJ, Szatmari P, Maclean JE, et al. Reliability and Accuracy of Differentiating Pervasive Developmental Disorder Subtypes. J Am Acadc Child Adoles Psychiatry. 1998;37:278–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce K, Carter C, Weinfeld M, et al. Detecting, Studying, and Treating Autism Early: The One-Year Well-Baby Check-Up Approach. J Pediatrics. 2011;159:458–65.e 1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertrand J, Mars A, Boyle C, Bove F, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Decoufle P. Prevalence of Autism in a United States Population: The Brick Township, New Jersey, Investigation. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1155–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children: confirmation of high prevalence. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1133–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholas JS, Charles JM, Carpenter LA, King LB, Jenner W, Spratt EG. Prevalence and characteristics of children with autism-spectrum disorders. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, et al. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP) Lancet. 2006;368:210–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fombonne E. Epidemiological trends in rates of autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(Suppl 2):S4–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King M, Bearman P. Diagnostic change and the increased prevalence of autism. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1224–34. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice C. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders - Autism and Developmental disabilities Monitoring Network, United States, 2006. CDC - Surveillance Summaries. 2009;58:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning SE, Davin CA, Barfield WD, et al. Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorders in Massachusetts birth cohorts, 2001-2005. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1043–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer RF, Blanchard S, Jean CR, Mandell DS. School District Resources and Identification of Children With Autistic Disorder. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:125–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.023077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnusson P, Saemundsen E. Prevalence of autism in Iceland. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:153–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1010795014548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakrabati S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorder in preschool children. JAMA. 2001;285:3093–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Gordon K, Wirrell E, Dooley JM. Incidence of epilepsy in childhood and adolescence: a population-based study in Nova Scotia from 1977 to 1985. Epilepsia. 1996;37(1):19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association AP. DSM-5 Development. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luyster RJ, Kuban KCK, O’Shea TM, et al. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers in extremely low gestational age newborns: individual items associated with motor, cognitive, vision and hearing limitations. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25:366–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryson SE, Clark BS, Smith IM. First report of a Canadian epidmiological study of autistic syndromes. J Child Psychol Psychiat. 1988;29:433–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher B, Dezort C, Nordli DR, Berg AT. Evaluating the use of routine developmental and autism screening in epilepsy care settings. Baltimore, MD: American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting; 2011. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sevin JA, Bowers-Stephens C, Crafton CG. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents with developmental disabilities: longitudinal data on diagnostic disagreement in 150 clients. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2003;34:147–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1027346108645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saemundsen E, Juliusson H, Hjaltested S, et al. Prevalence of autism in an urban population of adults with severe intellectual disabilities--a preliminary study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54:727–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop DVM, Whitehouse AJO, Watt HJ, Line EA. Autism and diagnostic substitution: evidence from a study of adults with a history of developmental language disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:341–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.La Malfa G, Lassi S, Bertelli M, Salvini R, Placidi GF. Autism and intellectual disability: a study of prevalence on a sample of the Italian population. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2004;48:262–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volkmar FR, State M, Klin A. Autism and autism spectrum disorders: diagnostic issues for the coming decade. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:108–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dykens EM. Psychopathology in children with intellectual disability. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:407–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Bildt A, Sytema S, Ketelaars C, Kraijer D, Volkmar F, Minderaa R. Measuring Pervasive Developmental Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Mental Retardation: A Comparison of Two Screening Instruments Used in a Study of the Total Mentally Retarded Population from a Designated Area. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:595–605. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005997.92287.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shattuck PT. Diagnostic substitution and changing autism prevalence. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1438–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shattuck PT. The contribution of diagnostic substitution to the growing administrative prevalence of autism in US special education. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1028–37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, et al. The incidence of clinically diagnosed versus research-identified autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1997: results from a retrospective, population-based study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:464–70. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0645-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandell DS, Thompson WW, Weintraub ES, DeStefano F, Blank MB. Trends in Diagnosis Rates for Autism and ADHD at Hospital Discharge in the Context of Other Psychiatric Diagnoses. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:56–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer RF, Blanchard S, Jean CR, Mandell DS. School District Resources and Identification of Children With Autistic Disorder. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:125–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.023077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.(IDEA) IWDEAo. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Goverment U, ed Pub L No 101-476 104 Stat 1142. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nassar N, Dixon G, Bourke J, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in young children: effect of changes in diagnostic practices. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1245–54. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senecky Y, Chodick G, Diamond G, Lobel D, Drachman R, Inbar D. Time trends in reported autistic spectrum disorders in Israel, 1972-2004. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009;11:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skellern C, Schluter P, McDowell M. From complexity to category: responding to diagnostic uncertainties of autistic spectrum disorders. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:407–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steffenburg S, Gillberg C. Autism and autistic-like conditions in Swedish rural and urban areas: a population study. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:81–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charman T, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP) Psychol Med. 2011;41:619–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryson SE, Smith IM. Epidemiology of autism: prevalence, associated characteristics, and implications for reserach and service delivery. MR DD Research Reviews. 1998;4:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baron-Cohen S, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, Ashwin E, Chakrabarti B, Knickmeyer R. Why are autism spectrum conditions more prevalent in males? PLoS Biol. 2011;9(6):e1001081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newschaffer CJ, Croen LA, Daniels J, et al. The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:235–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berg AT. Epilepsy, cognition, and behavior: The clinical picture. Epilepsia. 2011;52:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ellenberg JH, Hirtz DG, Nelson KB. Age at onset of seizures in young children. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:127–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Camfield C, Camfield P. Preventable and Unpreventable Causes of Childhood-Onset Epilepsy Plus Mental Retardation. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e52–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berg AT, Langfitt JT, Testa FM, et al. Global Cognitive Function in Children with Epilepsy: A community-based study. Epilepsia. 2008;49:608–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geerts A, Brouwer O, van Donselaar C, et al. Health perception and socioeconomic status following childhood-onset epilepsy: The Dutch study of epilepsy in childhood. Epilepsia. 2011;52:2192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dulac O. Epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsia. 2001;42(Suppl 3):23–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042suppl.3023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leung HT, Ring H. Epilepsy in four genetically determined syndromes of intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01505.x. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vasconcellos E, Wyllie E, Sullivan S, et al. Mental retardation in pediatric candidates for epilepsy surgery: The role of early seizure onset. Epilepsia. 2001;42:268–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.12200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cormack F, Cross JH, Isaacs E, et al. The development of intellectual abilities in pediatric temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:201–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tuchman RF, Rapin I, Shinnar S. Autistic and dysphasic children. II: Epilepsy. Pediatrics. 1991;88:1219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T. A longitudinal study of epilepsy and other central nervous system diseases in individuals with and without a history of infantile autism. Brain and Dev. 2011;33:361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong V. Epilepsy in children with autistic spectrum disorder. J Child Neurol. 1993;8:316–22. doi: 10.1177/088307389300800405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pavone P, Incorpora G, Fiumara A, Parano E, Trifiletti RR, Ruggieri M. Epilepsy is not a prominent feature of primary autism. Neuropediatrics. 2004;35:207–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T. Epilepsy and other neurological diseases in the parents of children with infantile autism. A case control study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2008;39:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bisulli F, Vignatelli L, Naldi L, et al. Increased frequency of arousal parasomnias in families with nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy: A common mechanism? Epilepsia. 2010;51:1852–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim HL, Donnelly JH, Tournay AE, Book TM, Filipek P. Absence of seizures despite high prevalence of epileptiform EEG abnormalities in children with autism monitored in a tertiary care center. Epilepsia. 2006;47:394–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Akihiro Y. Correlation between EEG abnormalities and symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Brain Dev. 2010;32:791–8. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chez MG, Chang M, Krasne V, Coughlan C, Kominsky M, Schwartz A. Frequency of epileptiform EEG abnormalities in a sequential screening of autistic patients with no known clinical epilepsy from 1996 to 2005. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saemundsen E, Ludvigsson P, Hilmarsdottir I, Rafnsson V. Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children with Seizures in the First Year of Life: A Population-Based Study. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1724–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berg A, Plioplys S, Tuchman R. Risk and Correlates of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children with Epilepsy: a Community-Based Study. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:537 –47. doi: 10.1177/0883073810384869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zeng LH, Rensing NR, Zhang B, Gutmann DH, Gambello MJ, Wong M. TSC2 gene inactivation causes a more severe epilepsy phenotype than TSC1 inactivation in a mouse model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:445–54. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waltereit R, Japs B, Schneider M, de Vries PJ, Bartsch D. Epilepsy and TSC2 haploinsufficiency lead to autistic-like social deficit behaviors in rats. Behav Genet. 2011;41:364–72. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li B-M, Liu X-R, Yi Y-H, et al. Autism in Dravet syndrome: Prevalence, features, and relationship to the clinical characteristics of epilepsy and mental retardation. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;21(3):291–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Specchio N, Balestri M, Trivisano M, et al. Electroencephalographic Features in Dravet Syndrome: Five-Year Follow-Up Study in 22 Patients. J Child Neurol. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0883073811419262. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Clark DF, Roberts W, Daraksan M, et al. The prevalence of autistic spectrum disorder in children surveyed in a tertiary care epilepsy clinic. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1970–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weintraub K. Autism counts. Nature. 2011;479:22–4. doi: 10.1038/479022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Michelson DJ, Shevell MI, Sherr EH, Moeschler JB, Gropman AL, Ashwal S. Genetic and metabolic testing on children with global developmental delay. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2011;77:1629–35. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182345896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scheffer IE. Genetic testing in epilepsy. what should you be doing? Epilepsy Curr. 2011;11:107–11. doi: 10.5698/1535-7511-11.4.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]