Abstract

Quantification of blood oxygen saturation on the basis of a measurement of its magnetic susceptibility demands knowledge of the difference in volume susceptibility between fully oxygenated and fully deoxygenated blood (Δχdo). However, two very different values of Δχdo are currently in use. In this work we measured Δχdo as well as the susceptibility of oxygenated blood relative to water, Δχoxy, by MR susceptometry in samples of freshly drawn human blood oxygenated to various levels, from 6 to 98% as determined by blood gas analysis. Regression analysis yielded 0.273 ± 0.006 and − 0.008 ± 0.003 ppm (cgs) respectively, for Δχdo and Δχoxy, in excellent agreement with previous work by Spees et al (MRM 2001;45:533–542).

Keywords: MR oximetry, MR susceptometry, Susceptibility imaging, Blood oxygen saturation

Introduction

Hemoglobin is derived from the words ‘heme’ meaning iron and ‘globin’ referring to its globular shape. The heme iron transitions from a low-spin state in oxyhemoglobin to a high-spin state in deoxyhemoglobin accounting for the former being diamagnetic and the latter paramagnetic. This oxidation state dependence of hemoglobin’s magnetic properties is the basis of contrast for various MRI methods such as blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) MRI (1), susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) (2), detection of acute hemorrhage (3), etc. While the above methods exploit qualitative differences in bulk magnetic susceptibility between oxy and deoxy-hemoglobin, their quantification enables determination of intravascular oxygen saturation.

In recent years several articles have appeared in which venous oxygen saturation was quantified by magnetic resonance techniques (2,4–8). These approaches can be broadly classified as T2 (7–8) and T2’ (6) based intravascular and extravascular methods, and susceptibility-based phase methods (4,9). The former rely on an empirical relationship to derive oxygen saturation from relaxation rates while the latter are essentially calibration-free. Phase methods are based on an exact solution of Laplace’s equation for the scalar magnetic potential, yielding a simple equation of the fractional induced field inside, relative to the field outside the vessel. The induced field can be translated to oxygen saturation values by approximating the vessel as a long cylinder combined with the knowledge of the volume susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and deoxygenated blood (Δχdo) and hematocrit (Hct). Haacke et al used the above approach to estimate oxygen saturation in cerebral pial veins (4). Since then, several groups have applied the method for various in vivo applications (5,10–12). However, much of the prior work has relied on two very different values of Δχdo, 0.18 ppm (13) and 0.27 ppm (14) (CGS units), yielding substantially different oxygen saturations. Although several prior studies have evaluated this constant in various ways, no consensus appears to exist on its actual value (13–16).

Phase based oxygen saturation measurements have recently been used to evaluate global and regional cerebral oxygen extraction fractions (OEF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption (CMRO2) at rest as well as during metabolic and motor tasks (10,12,17–18). The soundness and reliability of the results of these experiments is incumbent on the accuracy of the derived venous oxygen saturation. Thus, knowledge of the correct value of Δχdo is of paramount importance.

In this work we aimed to measure Δχdo using a framework similar to that utilized by Weisskoff et al (13). The experiments were planned to simulate in vivo conditions and to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies. The methodology used in the present work has previously been shown to yield accurate and reliable susceptibility values(19). Additionally, we examined potential sources of error in oxygen saturation derived by MR susceptometry and compared these to values obtained by blood gas analysis, widely regarded as the clinical gold standard.

Methods

Blood Preparation

Fresh whole-blood was collected from the antecubital vein of seven healthy human volunteers via venipuncture under an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocol. The samples were drawn in 7mL K2EDTA (1.7mg per mL of blood) Vacutainer tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA). Following collection the blood was stored over ice and immediately transferred to the hematology lab for preparation. All blood specimens were used within 6 hours after collection.

The samples were pipetted into 2mL large-surface-area cylindrical tubes (diameter = 20mm, height = 6mm) to ensure maximal exposure to the diffusing gases and placed into an Eppendorf Thermomixer (New Brunswick, NJ, USA) via a custom-designed mount. This mount had an air-tight seal with inlet/outlet nozzles for adding gases. Subsequently, the blood was oxygenated to varying levels (range: 6–98 %) by either exposure to room air or a continuous stream of N2 gas, while being maintained at 37°C. To prevent the RBCs from settling or foaming and to ensure maximal surface area for gas diffusion, the samples were continuously agitated. The samples had variable incubation periods to achieve their desired level of oxygenation (verified by blood gas analysis).

Blood samples from multiple large surface-area 2mL tubes were transferred into 6mL glass cylindrical tubes (diameter: 10 mm; height: 75mm) and sealed with a rubber stopper in preparation for MR scanning. Subsequently, the blood was injected into the MR sample tube via an inflow needle and another needle was placed for air outflow. The above procedure ensured that the tubes were filled completely with no remaining air spaces. The sample tubes were gently tumbled to prevent the blood from settling and maintained at a temperature of 37°C.

Four to five air-tight blood samples of different oxygenation were prepared per subject in the above manner (total of 30 samples with variable oxygenation levels for the entire study). The samples for each subject were placed in a cylindrical container filled with distilled water at 37°C and brought to the MRI suite for scanning. The setup in MR scanner included a heating pad to ensure a constant temperature of 37°C throughout the experiment. Care was taken to scan the samples quickly (less than 1.5min after they were placed in the scanner) to prevent red blood cell (RBC) settling. Prior work had shown that settling of RBCs can substantially affect the NMR line shape; with settling occurring within 2–3 minutes (14). After MRI, oxygen saturation level and hematocrit in each tube were re-measured in the hematology lab using the Radiometer Blood Gas Analyzer (Model: ABL 725, Radiometer Medical ApS, and Denmark). To examine the precision of the phase-based MRI method, samples from the last three subjects were scanned five times each. Between measurements, the sample tube assembly was removed from the scanner and gently tumbled to prevent RBC settling.

MR Protocol

All MRI measurements were performed on a 3T Siemens Tim Trio system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a 12-channel head coil. The cylindrical container was placed in the scanner with its long axis parallel to the B0 field. A 2D gradient-recalled Echo (GRE) sequence was used to obtain axial phase maps with the following imaging parameters, voxel size: (voxel size =1×1×5 mm3, FOV = 76mm × 76 mm, flip angle = 25°, TE = 7.2ms, TR = 70ms, number of echoes = 2, echo spacing (ΔTE)= 2.5ms, total scan time ~11s). Phase difference (Δϕ) was computed by taking the difference of the phase images from the two echoes.

The susceptibility differences between various compartments (such as air, tissue etc.) cause field inhomogeneities and result in low spatial-frequency modulations of the phase signal. To minimize this interfering effect a retrospective correction method was implemented, which approximates the field inhomogeneity by a second-order polynomial. The compartments where oxygen saturation was to be determined were masked out and the phase difference image was weighted with the corresponding masked magnitude image. The robustness and accuracy of the method for quantifying susceptibility has been previously validated by some of the present authors (19). The experimental set-up, duplicated in the current work, consisted of an array of sample tubes filled with Gd-doped water of various concentrations and known volume susceptibilities.

The susceptibility difference (Δχ) between blood and water was computed from the phase difference (Δϕ) between an ROI placed inside the cross sectional area of each tube and the surrounding water as

| (1) |

Δχdo was obtained from the slope of Δχ/Hct, where Hct are the individual hematocrit levels, and the concentration of deoxy-Hb (1-HbO2) obtained from blood gas analysis (Eq 2):

| (2) |

where Δχoxy is the susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated blood and water. In this model it is assumed that the χplasma~ χwater (14).

Statistical Analysis

Regression lines were calculated using standard linear regression. Bland-Altman method was used to evaluate agreement between blood gas and phase based oxygen saturation measurements. The Bland-Altman test is a statistical method to compare two different methods of measurement and test if one can be replaced by another. The mean difference between the two methods for measuring oxygen saturation (‘bias’) and 95% limits of agreement (1.96 × Standard deviation) are then calculated. In order to be equivalent, 95% limits must include 95% of differences between the two measurement methods (20). All analyses were performed using JMP (Version 7, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

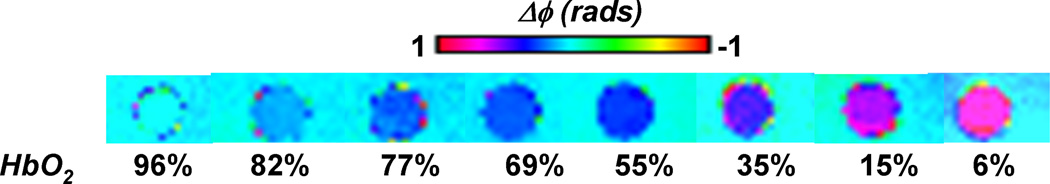

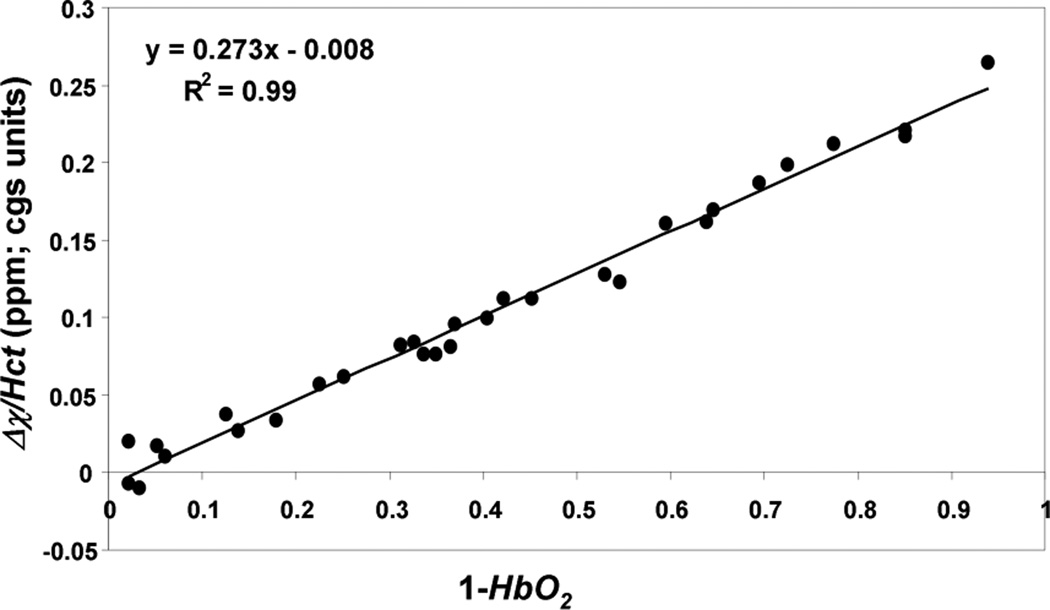

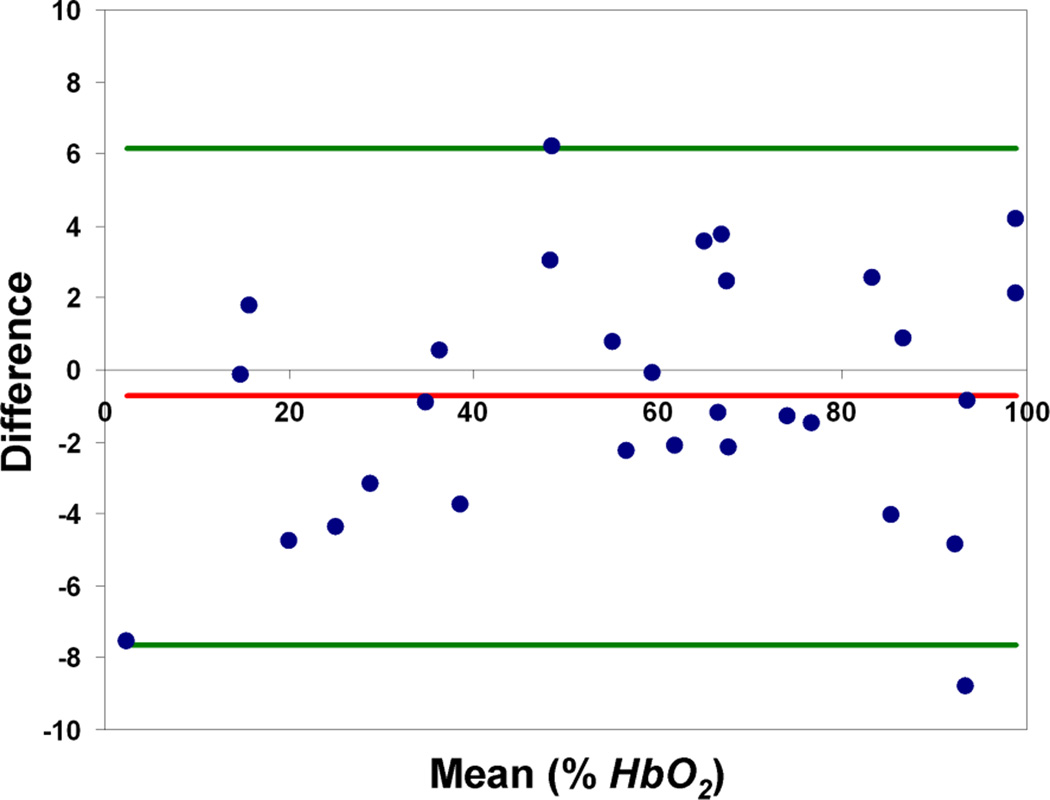

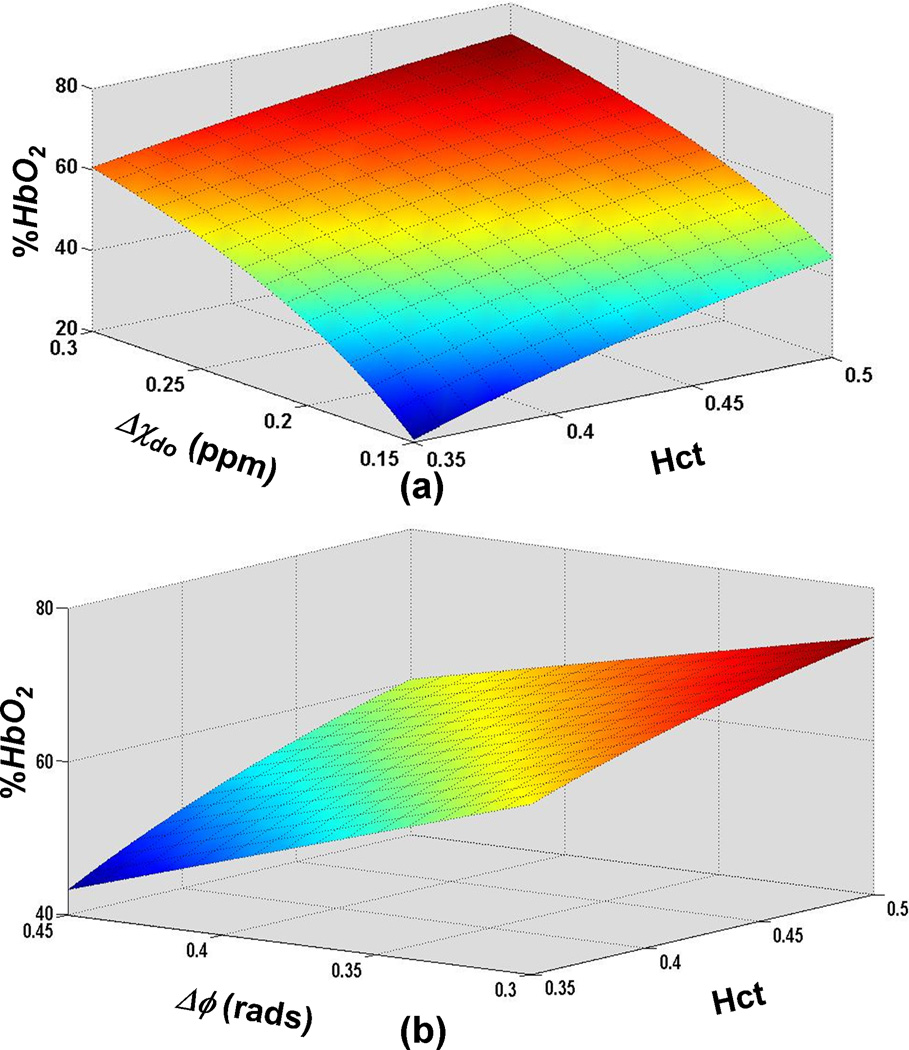

Representative phase difference maps for calculating blood susceptibility are shown in Figure 1. The slope of the regression line of Δχ/Hct versus deoxygenation yielded a value of 0.273 ± 0.006 ppm (CGS units) for Δχdo and a y-intercept of − 0.008 ± 0.003 ppm corresponding to Δχoxy, the susceptibility of fully oxygenated blood relative to water (Figure 2). Hematocrit and deoxygenation (1-HbO2) ranges for the measurements were 36 to 49% and 2 to 94%, respectively. Repeated measurements of blood susceptibility at a given oxygen saturation and hematocrit level yielded a coefficient of variation of <5%. Figure 3 shows Bland-Altman plots for assessing the agreement between phase and blood gas analyzer derived oxygen saturation measurements. The mean bias and limits of agreement were −0.7% and ±6.4 % HbO2, respectively. A 95% confidence interval for the mean yielded a lower and upper limit of −2.0 and 0.6% HbO2, respectively, suggesting that the two measurements are not significantly different from one another. Figure 4 illustrates the sensitivity of the derived oxygen saturation to hematocrit, Δχdo and Δϕ. A fractional error of σHct,, σΔχdo and σΔϕ in Hct, Δχdo and phase (Δϕ), respectively, introduces an absolute error ε HbO2,

| (3) |

in the derived oxygen saturation estimates; where (see Appendix for derivation of Eq. 3). Thus, errors in the above parameters affect lower oxygen saturation values more severely. Additionally, for a given phase value the sensitivity of HbO2 measurements to uncertainties in Hct and Δχdo is greatest at low values of Hct and Δχdo as is evident from the increased slope of the surface plot in Figure 4a at low values of these parameters. Figure 4b illustrates that phase errors lead to greater absolute errors in HbO2 at low Hct values.

Figure 1.

Representative phase difference images of cylindrical sample tubes filled with blood oxygenated to various HbO2 levels, oriented parallel to the B0 field and immersed in distilled water. Note the change in contrast at different oxygenation levels.

Figure 2.

Susceptibility difference (Δχ) between blood and surrounding distilled water normalized to individual hematocrit (Hct) level in each subject plotted against the level of deoxygenation. The slope of the regression line represents the susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and deoxygenated blood (Δχdo) and intercept the susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated blood and water (Δχoxy).

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plots showing the agreement between MR susceptometry and Blood Gas Analyzer derived oxygen saturation values based on Δχdo = 0.27ppm and Δχoxy = 0.008 ppm. The red and green lines indicate the mean bias and the limits of agreement (1.96 × standard deviation), respectively.

Figure 4.

Surface plot of HbO2 as a function of (a) susceptibility difference between fully deoxygenated and fully oxygenated blood, Δχdo, and hematocrit, Hct, for a phase value corresponding to 65% HbO2 for Hct = 0.42 and Δχdo=0.27ppm (b) phase difference (Δϕ) and Hct for Δχdo = 0.27ppm. The plots illustrate that errors in HbO2 measurement due to uncertainties in Δχdo, Hct and Δϕ scale with the level of deoxygenation.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this work we determined the bulk volume susceptibility difference between fully oxygenated and deoxygenated human blood by varying blood oxygen saturation ex-vivo in a controlled environment. The ability of the proposed phase difference method and processing technique to determine Δχ with high precision and accuracy has been verified previously (5,19). Further, we evaluated the agreement of MR susceptometry derived oxygen saturation measurements with the clinical gold standard, blood gas measurements.

The value of Δχdo obtained in the present study (0.273 ± 0.006 ppm) is in excellent agreement with the work of Spees et al based on both NMR and SQUID magnetometry (14). They obtained Δχdo = 0.27 ppm using both methods. Additional support for this value comes from calculations based on Cerdonio’s model using the magnetic moment of deoxyhemoglobin as initially determined by Pauling et al (14–15).

Our measurement of Δχdo is also in good agreement with earlier magnetic cell capture experiments by Kondroskii et al who studied the cellular trajectories of single RBC’s in response to a known magnetic field, from which they deduced a Δχdo value of 0.29ppm (21). More recent and technologically improved experiments by Zborowski et al on RBC magnetophoretic motilities yielded a value of 0.26ppm for Δχdo (22).

However, our measured value of Δχdo differs significantly from Weisskoff et al’s (13) who examined the phase difference between whole blood oxygenated to various levels and distilled water. Based on oxygen saturation determined by blood gas analysis, they obtained a Δχdo value of 0.18ppm. This value is of the same order as an early rough estimate by Thulborn et al (16).

Although our experimental methodology somewhat resembles that used by Weisskoff, who performed field mapping with an asymmetric spin-echo sequence using an echoplanar readout, there are notable issues with that study that could have caused systematic errors. First, they used expired human blood. Hemorheological and hematological parameters are known to alter significantly with storage age. For example, erythrocytes swell, deform, lyse, become rigid and form micro-aggregates (23). Additionally, blood chemistry can change substantially, with pH and 2, 3-DPG levels dropping with longer durations ex-vivo (23–24). These changes significantly alter hemoglobin’s oxygen binding affinity. Second, there was no mention of any precautions taken to prevent blood from settling, which is known to substantially affect the NMR line shape within 2–3 minutes (14). Thus, the conditions in Weisskoff and Kiihne’s experiments do differ substantially from those of freshly drawn or in vivo blood.

In addition to the value for Δχdo, the intercept of the graph in Figure 2 provides an estimate for the value Δχoxy. The observed value for Δχoxy corroborates that fully oxygenated blood is slightly more diamagnetic than water. This finding was first reported by Pauling et al (25). However, experiments by Cerdonio et al in the late 1970s put this into question. Their measured magnetic moment for oxyhemoglobin suggested a possible paramagnetic contribution (26–27). In line with our measurements, recent work by Savicki et al and Spees et al (14,28) has not provided evidence for such paramagnetism.

Most prior studies in which whole-blood oxygen saturation via the long-cylinder approximation and phase difference method was measured have ignored the contribution of Δχoxy in equation 2; assuming its effect to be negligible (4–5,11,29). Our results indicate that neglecting this contribution can introduce a slight bias (on the order of 2–3% HbO2) towards overestimating the oxygen saturation values. The effects of ignoring the diamagnetic contribution from fully oxygenated blood can be significant in some hematologic disorders. A case in point is sickle-cell disease (SCD). Sakhnini et al (30), who examined the magnetic properties of hemoglobin in SCD patients, found that fully oxygenated HbS is more diamagnetic than normal hemoglobin.

Our results indicate that the mean bias ± limits of agreement between MR susceptometry derived and blood gas analyzer measured HbO2 values were −0.7±6.4%. The data thus suggest that HbO2 can be quantified by MR susceptometry with clinically acceptable levels of agreement. The model used to derive whole-blood oxygen saturation from susceptibility measurements relies on the accuracy of Hct, Δχdo and phase as errors in their values are propagated into the derived oxygen saturation values. As predicted by Equation 3 and illustrated in Figure 4, uncertainties in these parameters cause the greatest errors at low oxygen saturation values as the errors scale according to the level of deoxygenation (1-HbO2). Thus, a population based estimate of Hct might suffice when using MR susceptometry to determine oxygen saturation in arterial vessels. However, an accurate measurement of Hct is critical when applying this method in vessels where low oxygen saturations are expected. In general, uncertainties in HbO2 estimates are dominated by errors in Hct and Δχdo at low oxygen saturations and by low phase SNR at high oxygenation levels.

It should be noted that our measured value Δχdo might not be applicable to all clinical scenarios. Our experimental Δχdo was calculated with normal adult hemoglobin. Caution must be exercised when using this constant for oxygen saturation determination in individuals with variable hemoglobin types (e.g. HbF, HbS etc.). There is some disagreement in literature on the possible contribution of steric heme-heme interactions on the net dipole moment of hemoglobin (calculated per heme). Traditionally myoglobin has been used to study such interactions as it consists of a single heme group conjugated to a globin chain. Thus it is representative of true magnetic moment of heme attached to globin in the absence of any heme-heme interactions. While early experiments on the magnetic moment of myoglobin found values similar to those obtained for hemoglobin (per heme) (31), later experiments contradicted this finding (32). Such interactions, if present, could have implications on the magnetic moment of deoxyHb and hence Δχdo. It is conceivable that in the event of variations in globin chains (e.g. individuals with hemoglobinopathies), the aforementioned steric heme-heme interactions could be affected, amongst other variables, thereby altering Δχdo.

In conclusion, our results strongly support a Δχdo value of 0.27ppm for normal adult human blood. Deviations from the present value in prior work are likely due to experimental inadequacies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Helen Peachey for help with collection of blood samples. This work was supported by grants K01HL103186 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (OA) and NIH- RC1-HL099861 and R21-HD069390 (FW).

Appendix

From Equations 1 and 2, HbO2 can be calculated as,

| (A1) |

Constants other than Hct, Δχdo and Δϕ are user specified or empirical and can be replaced by constant k for simplicity, yielding.

| (A2) |

Using basic rules of error propagation, the absolute error (ε) in HbO2 can be estimated as

| (A3) |

Computing partial derivatives and substituting dΔϕ = Δϕ · σΔϕ, dHct = Hct · σHct and dΔχdo = Δχdo·σΔχdo, with σ representing the fractional error, yields

| (A4) |

Rearranging and substituting Eq. A2, gives

| (A5) |

References

- 1.Ogawa S, Tank DW, Menon R, Ellermann JM, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ugurbil K. Intrinsic signal changes accompanying sensory stimulation: functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(13):5951–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichenbach JR, Essig M, Haacke EM, Lee BC, Przetak C, Kaiser WA, Schad LR. High-resolution venography of the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. MAGMA. 1998;6(1):62–69. doi: 10.1007/BF02662513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomori JM, Grossman RI, Goldberg HI, Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT. Intracranial hematomas: imaging by high-field MR. Radiology. 1985;157(1):87–93. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.1.4034983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haacke EM, Lai S, Reichenbach JR, Kuppusamy K, Hoogenraad FGC, Takeichi H, Lin W. In Vivo Measurement of Blood Oxygen Saturation Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Direct Validation of the Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Concept in Functional Brain Imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 1997;5:341–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:5<341::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langham MC, Magland JF, Epstein CL, Floyd TF, Wehrli FW. Accuracy and precision of MR blood oximetry based on the long paramagnetic cylinder approximation of large vessels. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(2):333–340. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An H, Lin W. Quantitative measurements of cerebral blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(8):1225–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200008000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Ge Y. Quantitative evaluation of oxygenation in venous vessels using T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(2):357–363. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright GA, Hu BS, Macovski A. 1991 I.I. Rabi Award. Estimating oxygen saturation of blood in vivo with MR imaging at 1.5 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;1(3):275–283. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoogenraad FG, Reichenbach JR, Haacke EM, Lai S, Kuppusamy K, Sprenger M. In vivo measurement of changes in venous blood-oxygenation with high resolution functional MRI at 0.95 tesla by measuring changes in susceptibility and velocity. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(1):97–107. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan AP, Benner T, Bolar DS, Rosen BR, Adalsteinsson E. Phase-based regional oxygen metabolism (PROM) using MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mrm.23050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández-Seara M, Detre JA, Techawiboonwong A, Wehrli FW. MR susceptometry for measuring global brain oxygen extraction. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(5):967–973. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain V, Langham MC, Wehrli FW. MRI estimation of global brain oxygen consumption rate. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;26 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisskoff RM, Kiihne S. MRI susceptometry: image-based measurement of absolute susceptibility of MR contrast agents and human blood. Magn Reson Med. 1992;24(2):375–383. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910240219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spees WM, Yablonskiy DA, Oswood MC, Ackerman JJ. Water proton MR properties of human blood at 1.5 Tesla: magnetic susceptibility, T(1), T(2), T*(2), and non-Lorentzian signal behavior. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(4):533–542. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabry ME, San George RC. Effect of magnetic susceptibility on nuclear magnetic resonance signals arising from red cells: a warning. Biochemistry. 1983;22(17):4119–4125. doi: 10.1021/bi00286a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thulborn KR, Waterton JC, Matthews PM, Radda GK. Oxygenation dependence of the transverse relaxation time of water protons in whole blood at high field. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;714(2):265–270. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain V, Langham MC, Floyd TF, Jain G, Magland JF, Wehrli FW. Rapid magnetic resonance measurement of global cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption in humans during rest and hypercapnia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(7):1504–1512. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain V, Jain G, Magland JF, Wehrli FW. Regional Cerebral Metabolic Rate of Oxygen Consumption in the Middle Cerebral Artery Territory. International Soceity of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Montreal,Canada. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langham MC, Magland JF, Floyd TF, Wehrli FW. Retrospective correction for induced magnetic field inhomogeneity in measurements of large-vessel hemoglobin oxygen saturation by MR susceptometry. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(3):626–633. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondroskii EI, Norina SB, Litvinchuk NV, Shalygin AN. Magnetic Susceptibility of Single Human Erythrocytes. Biofizika. 1981;26(6):1104–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zborowski M, Ostera GR, Moore LR, Milliron S, Chalmers JJ, Schechter AN. Red blood cell magnetophoresis. Biophys J. 2003;84(4):2638–2645. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sezdi M, Sonmezoglu M, Tekeli O, Ulgen Y, Emerk K. Changes in electrical and physiological properties of human blood during storage. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2005;7:6710–6713. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2005.1616043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett-Guerrero E, Veldman TH, Doctor A, Telen MJ, Ortel TL, Reid TS, Mulherin MA, Zhu H, Buck RD, Califf RM, McMahon TJ. Evolution of adverse changes in stored RBCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):17063–17068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708160104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauling L, Coryell CD. The Magnetic Properties and Structure of Hemoglobin, Oxyhemoglobin and Carbonmonoxyhemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1936;22(4):210–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerdonio M, Congiu-Castellano A, Mogno F, Pispisa B, Romani GL, Vitale S. Magnetic properties of oxyhemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74(2):398–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cerdonio M, Morante S, Vitale S, Dalvit C, Russu IM, Ho C, de Young A, Noble RW. Magnetic and spectral properties of carp carbonmonoxyhemoglobin. Competitive effects of chloride ions and inositol hexakisphosphate. Eur J Biochem. 1983;132(3):461–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savicki JP, Lang G, Ikeda-Saito M. Magnetic susceptibility of oxy- and carbonmonoxyhemoglobins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(17):5417–5419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain V, Langham MC, Wehrli FW. MRI estimation of global brain oxygen consumption rate. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(9):1598–1607. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakhnini L. Magnetic measurements on human erythrocytes: Normal, beta thalassemia major, and sickle. Journal of Applied Physics. 2003;93(10) Part 2&3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor DS. The Magnetic Properties of Myoglobin and Ferrimyoglobin, and their Bearing on the Problem of the Existence of Magnetic Interactions in Hemoglobin. Journal of American Chemical Soceity. 1939;61(8):2150–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alpert Y, Banerjee R. Magnetic susceptibility measurements of deoxygenated hemoglobins and isolated chains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;405(1):144–154. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]