Abstract

Objectives

High-quality care for intensive care unit patients and families includes palliative care. To promote performance improvement, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Quality Measures Clearinghouse identified nine evidence-based processes of intensive care unit palliative care (Care and Communication Bundle) that are measured through review of medical record documentation. We conducted this study to examine how frequently the Care and Communication Bundle processes were performed in diverse intensive care units and to understand patient factors that are associated with such performance.

Design

Prospective, multisite, observational study of performance of key intensive care unit palliative care processes.

Settings

A surgical intensive care unit and a medical intensive care unit in two different large academic health centers and a medical-surgical intensive care unit in a medium-sized community hospital.

Patients

Consecutive adult patients with length of intensive care unit stay ≥5 days.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Between November 2007 and December 2009, we measured performance by specified day after intensive care unit admission on nine care process measures: identify medical decision-maker, advance directive and resuscitation preference, distribute family information leaflet, assess and manage pain, offer social work and spiritual support, and conduct interdisciplinary family meeting. Multivariable regression analysis was used to determine predictors of performance of five care processes. We enrolled 518 (94.9%) patients and 336 (83.6%) family members. Performances on pain assessment and management measures were high. In contrast, interdisciplinary family meetings were documented for <20% of patients by intensive care unit day 5. Performance on other measures ranged from 8% to 43%, with substantial variation across and within sites. Chronic comorbidity burden and site were the most consistent predictors of care process performance.

Conclusions

Across three intensive care units in this study, performance of key palliative care processes (other than pain assessment and management) was inconsistent and infrequent. Available resources and strategies should be utilized for performance improvement in this area of high importance to patients, families, and providers.

High-quality care for intensive care unit (ICU) patients and their families includes palliative care. The Institute of Medicine, all major societies representing critical care professionals, large-scale hospital networks, and government and industry healthcare payers agree that palliative care is a priority area for ICU quality improvement (1–5). As defined by a consensus of expert opinion (6) and by patients who have experienced intensive care and their families (7), domains of ICU palliative care quality include: patient care that maintains patients’ comfort, dignity, and personhood; timely, effective, and compassionate communication by clinicians with patients and families; alignment of medical decision-making with patients’ values, goals, and preferences; support for the family; and support for ICU clinicians (8).

To evaluate and improve care within these domains, the Voluntary Hospital Association, encompassing >2000 hospitals across the United States, sponsored development of the Care and Communication Bundle of nine process measures of the quality of ICU palliative care: identification of a medical decision-maker; determination of advance directive status; investigation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation preference; distribution of a family information leaflet; interdisciplinary family meeting; offer of social work support; offer of spiritual support; regular pain assessment; and appropriate pain management (9). This set of measures, which are time-triggered, focuses on key evidence-based processes that are feasible for a range of ICUs to perform and measure routinely (9). The Care and Communication Bundle is posted on the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse Web site of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (10), which screens quality measures by validity criteria. In a qualitative study, ICU patients and families broadly endorsed care processes in this bundle as important for high-quality care (7).

No previous studies have systematically or prospectively measured the extent to which ICU teams provide these core components of palliative care in routine clinical practice. The objective of our study was to examine how frequently the Care and Communication processes were performed in the care of critically ill patients receiving an extended period of ICU treatment. We also sought to understand patient factors that are associated with performance of these care processes, controlling for the ICU where the patient was admitted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This prospective observational study evaluated performance of care processes in the Voluntary Hospital Association Care and Communication Bundle for patients in three adult ICUs between November 2007 and December 2009. The sample included a surgical ICU and a medical ICU in two different large academic health centers and a medical-surgical ICU in a medium-sized community hospital. The ICUs varied by location, size, case mix, bed number, care model, and mortality rate. Pulmonary/critical care physicians staff the medical ICU, which has 14 beds and uses a mixed open–closed care model. In the surgical ICU with 10 beds, surgeons and anesthesiologists with critical care certification manage or co-manage patients. The general ICU is a 20-bed “open” unit with intensivist support for primary physician management.

Measures

Development and details of the Care and Communication Bundle have been previously described (9, 10). Domains for measurement were determined through literature review and expert consensus. Experts in measurement, palliative care, intensive care, and performance improvement led pilot testing and refined the measures iteratively.

Sample

The hospitals’ Institutional Review Boards approved the research. At each site, a trained research nurse enrolled all ICU adult patients with ICU length of stay ≥5 days. Informed consent was waived for patients because participation was limited to medical record review. On ICU day 6, the research nurse also enrolled patients’ family members who had responsibility for healthcare decision-making, visited the ICU at least once during the first 5 days, and provided informed consent. Patients were followed-up to discharge or death.

Procedures

The ICU palliative care process measures under study are grouped according to the ICU day (from ICU admission) by which the care process should be performed: day 1 (identify decision-maker, identify advance directive, identify resuscitation preference, provide family information leaflet, assess pain, manage pain); day 3 (offer social work support, offer spiritual support); and day 5 (conduct an interdisciplinary family meeting) (9, 10). Performance data were collected from medical records on day 6. The numerator for most measures was the number of patients receiving the care process and the denominator was the total patient number (10). Pain measures focused on the proportion of 4-hr patient–nurse intervals (up to six per day) in which the care process was performed. On ICU day 6, the research nurse interviewed family members and reviewed medical records and hospital databases to collect patients’ demographic and health status information and demographic information for family members.

Statistical Analyses

We described subjects’ characteristics and ICU performance of the palliative care processes with univariate and bivariate statistics. We used multiple logistic regression analyses (11) to examine the association of patient and family factors with performance on five of the nine measures, controlling for site. We included patients with an enrolled family member in these analyses. We did not include the measure for family information leaflet distribution because none was available at two sites when the study began. We also did not include the measures related to pain assessment and management because sites in the study were involved in national efforts, unrelated to our research, to increase monitoring and treatment of pain, as mandated by the Joint Commission. As explained in Results, we also did not present regression results for offer of spiritual support. Predictors in the models included patient age, gender, ICU diagnosis, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (12), Charlson comorbidity index (13), ICU length of stay, family members’ gender, religion, primary language, race/ethnicity, education, and relationship to patient, and ICU visit frequency. Because we hypothesized a priori that these variables were likely to be related to the outcomes, we included all such variables in our models rather than performing univariate screening. We screened all variables for collinearity. We analyzed data using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX); p ≤ .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Cohort Characteristics

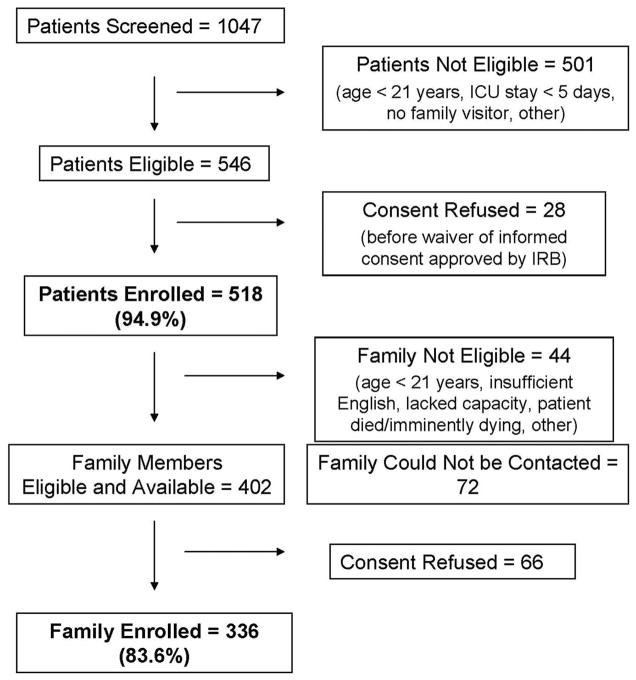

As shown in Figure 1, we enrolled 518 (94.9%) patients and 336 (83.6%) family members. Table 1 shows cohort characteristics. The average age of patients was 62.7 yrs. The majority of patients spoke English and were white. The majority of family members visited the ICU daily.

Figure 1. Recruitment of critically ill patients and their families.

ICU, intensive care unit; IRB, Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Patient and family characteristics

| Patient Characteristics (n = 518) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 62.7 (16.5) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 250 (48.3) |

| Male | 268 (51.7) |

| Religion, n (%) | |

| Catholic | 125 (24.1) |

| Protestant | 228 (44.0) |

| Jewish | 43 (8.3) |

| Other | 122 (23.6) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married/live with partner | 264 (51.0) |

| Other | 254 (49.0) |

| Language, n (%) | |

| English | 438 (84.6) |

| Other | 80 (15.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 333 (64.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 91 (17.6) |

| Hispanic | 66 (12.7) |

| Other | 28 (5.4) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |

| Medicare, Medicaid, Commercial | 432 (83.4) |

| Other | 86 (16.6) |

| Primary ICU diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Surgical | 88 (17.0) |

| Other | 430 (83.0) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.8) |

| Functional Independence Measure (Motor), mean (SD) | 77.9 (24.7) |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, mean (SD) | 28.1 (7.3) |

| ICU length of stay, median (intequartile range) | 10.0 (9.0) |

| Hospital length of stay, median (interquartile range) | 22.0 (25.0) |

| Vital status at ICU discharge, n (%) | |

| Alive | 432 (83.4) |

| Expired | 86 (16.6) |

| Vital status at hospital discharge, n (%) | |

| Alive | 356 (68.7%) |

| Expired | 162 (31.3%) |

| Site, n (%) | |

| A | 219 (42.3%) |

| B | 213 (41.1%) |

| C | 86 (16.6%) |

| Family characteristics (n = 336)

| |

| Age, mean (SD) | 54.9 (14.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 226 (67.3) |

| Male | 110 (32.7) |

| Relation to patient, n (%) | |

| Spouse/partner | 136 (40.5) |

| Other | 200 (59.5) |

| Religion, na (%) | |

| Catholic | 79 (23.5) |

| Protestant | 147 (43.8) |

| Jewish | 23 (6.8) |

| Other | 80 (23.8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married/live with partner | 244 (72.6) |

| Other | 92 (27.4) |

| Language, n (%) | |

| English | 307 (91.4) |

| Other | 29 (8.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White, not Hispanic | 222 (66.1) |

| Black, not Hispanic | 53 (15.8) |

| Hispanic | 48 (14.3) |

| Other | 13 (3.8) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| At least some college | 203 (60.4) |

| High school or less | 133 (39.6) |

| Patient Characteristics (n = 518)

| |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Employed | 186 (55.4) |

| Other | 150 (44.6) |

| Income, n (%) | |

| <$15,000 | 18 (5.3) |

| $15,000–$50,000 | 87 (25.9) |

| >$50,000 | 91 (27.1) |

| Preferred not to report income | 140 (41.7) |

| Number of days visited ICU, n (%) | |

| Every day | 190 (56.5) |

| At least 1 d but not every day | 146 (43.4) |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Numbers in religion categories do not add to 336 because some family members in the study did not report their religion.

Frequency of Performance of Care Processes

Table 2 presents frequencies for performance of each care process for all sites and for each individual site. Across all sites, prevalence of performance of specific care processes ranged from 8% for distribution of a family information leaflet to 80% for appropriate pain management. Of the processes evaluated for day 1, frequency of overall performance on the pain measures was highest (76% for assessment, 80% for management), whereas performance on other day 1 measures (identification of medical decision-maker, investigation for advance directive, determination of resuscitation status, distribution of family information leaflet) was lower (8%–43%). Approximately one-third of patients received an offer of spiritual support or social work support by day 3 after admission to the ICU. Performance of an interdisciplinary family meeting by day 5 was documented for <20% of patients.

Table 2.

Performance on care process measures

| Care Processes, n (%) | Site A Medical Intensive Care Unit (n = 219) | Site B General Medical/Surgical Intensive Care Unit (n = 213) | Site C Surgical Intensive Care Unit (n = 86) | All Sites (n = 518) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of medical decision-maker | 58 (26.4) | 111 (52.1) | 53 (61.6) | 222 (42.9) |

| Determination of advanced directive status | 8 (3.7) | 111 (52.1) | 41 (47.7) | 160 (30.9) |

| Investigation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation preference | 36 (16.4) | 164 (77.0) | 7 (8.1) | 207 (40.0) |

| Distribution of family information leafleta | 33 (15.1) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (3.5) | 39 (7.5) |

| Interdisciplinary family meeting conducted | 38 (17.4) | 18 (8.5) | 43 (50.0) | 99 (19.1) |

| Offer of social work support | 46 (21.0) | 110 (51.6) | 15 (17.4) | 171 (33.0) |

| Offer of spiritual support | 1 (0.5) | 127 (59.6) | 28 (32.6) | 156 (30.1) |

| Regular pain assessment (%)b | 96.8 | 48.3 | 92.9 | 76.0 |

| Appropriate pain management (%)c | 93.4 | 61.3 | 80.9 | 80.1 |

Sites B and C did not have family leaflets to distribute at the beginning of the study;

the denominator is the number of 4-hr patient–nurse intervals (maximum of six per day) during the intensive care unit stay;

the denominator is the number of 4-hr patient–nurse intervals (maximum of six per day) during the intensive care unit stay in which pain was assessed.

Performance varied greatly according to site, as shown in Table 2. The largest between-site differences were seen for determination of resuscitation preference (performance for 77%, 16%, and 8% of patients at sites B, A, and C, respectively) and for spiritual support (60%, 33%, and 1% at sites B, C, and A, respectively). No single site performed best on all nine measures or on a majority of these measures. At site A, documentation of performance was lacking for >70% of patients on all measures except pain assessment and management.

Predictors of Performance of Care Processes

Table 3 presents results for the multiple variable logistic regression analyses, including odds ratios and confidence intervals for predictors for each of five care processes in the Care and Communication Bundle. We were unable to estimate the relationship between predictors and offering spiritual support because site almost perfectly predicted offer of spiritual support. We excluded from this analysis the distribution of a family information leaflet because the leaflet was not available at two sites when the study began. We also did not include the measures related to pain assessment and management because sites in the study were involved in national efforts, unrelated to our research, to increase monitoring and treatment of pain, as mandated by the Joint Commission. The patient’s risk of death attributable to comorbid conditions, as measured by Charlson comorbidity index, was associated with an increased probability of performance of the majority of care processes. Site also predicted performance of the majority of these processes.

Table 3.

Predictors of care process measuresa

| Predictors | Outcomeb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of Medical Decision-Maker

|

Determination of Advanced Directive Status

|

Investigation of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Preference

|

||||

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Patient agec | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | .354 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.504 | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | .026 |

| Female patient gender | 0.63 (0.37–1.09) | .096 | 1.02 (0.55–1.88) | 0.960 | 0.79 (0.40–1.56) | .490 |

| Nonsurgical ICU diagnosis | 0.61 (0.24–1.58) | .309 | 1.05 (0.41–2.71) | 0.915 | 1.20 (0.35–4.11) | .769 |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Scorec | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | .548 | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.069 | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | .059 |

| Charlson indexc | 1.14 (1.04–1.25) | .003 | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | 0.156 | 0.98 (0.88–1.10) | .754 |

| ICU Length of Stayc | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | .895 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.200 | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | .420 |

| Female family gender | 1.71 (0.97–3.02) | .065 | 1.71 (0.87–3.33) | 0.117 | 0.98 (0.49–1.96) | .965 |

| Family religion (reference = Protestant) | ||||||

| Catholic | 1.14 (0.47–2.72) | .775 | 0.94 (0.37–2.38) | 0.892 | 0.66 (0.20–2.11) | .479 |

| Jewish | 0.59 (0.14–2.48) | .474 | 0.51 (0.10–2.62) | 0.420 | 0.14 (0.02–0.94) | .043 |

| Other | 1.17 (0.48–2.85) | .724 | 0.41 (0.15–1.10) | 0.078 | 0.45 (0.14–1.52) | .202 |

| Family language: non-English vs. English | 1.38 (0.48–4.01) | .550 | 4.88 (1.02–23.23) | 0.047 | 1.09 (0.31–3.81) | .898 |

| Family race (reference = white) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.03 (0.44–2.39) | .945 | 0.78 (0.29–2.11) | 0.621 | 0.78 (0.24–2.47) | .668 |

| Hispanic | 0.31 (0.10–0.91) | .034 | 0.03 (0.00–0.67) | 0.026 | 0.44 (0.12–1.54) | .198 |

| Other | 0.84 (0.24–2.99) | .786 | 0.33 (0.07–1.64) | 0.175 | 0.32 (0.06–1.59) | .161 |

| Family education level: some college vs. high school or less | 1.45 (0.85–2.45) | .171 | 1.09 (0.60–1.95) | 0.784 | 1.36 (0.69–2.69) | .380 |

| Relationship to patient: not spouse/partner vs. all other | 0.98 (0.57–1.66) | .929 | 1.00 (0.56–1.80) | 0.989 | 1.56 (0.79–3.08) | .202 |

| Family visited every day vs. at least once but not every day | 1.88 (1.11–3.20) | .019 | 1.56 (0.87–2.78) | 0.135 | 7.92 (3.72–16.88) | <.001 |

| Site (reference = site A) | ||||||

| B | 2.37 (0.85–6.62) | .099 | 5.55 (1.64–18.74) | 0.006 | 11.32 (3.02–42.49) | <.001 |

| C | 2.62 (0.80–8.61) | .111 | 17.72 (4.56–68.87) | <.001 | 0.25 (0.05–1.29) | .097 |

| Predictors | Interdisciplinary Family Meeting Conducted

|

Offer of Social Work Support

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Patient agec | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | .633 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | .198 |

| Female patient gender | 0.53 (0.26–1.10) | .088 | 0.52 (0.29–0.93) | .026 |

| Nonsurgical ICU diagnosis | 0.72 (0.20–2.54) | .609 | 1.38 (0.48–3.98) | .548 |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scorec | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | .269 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | .568 |

| Charlson indexc | 1.17 (1.05–1.30) | .006 | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | .043 |

| ICU length of stayc | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | .605 | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | .762 |

| Female family gender | 0.65 (0.31–1.37) | .255 | 1.07 (0.59–1.95) | .814 |

| Family religion (reference = Protestant) | ||||

| Catholic | 0.67 (0.19–2.28) | .517 | 1.86 (0.69–5.05) | .223 |

| Jewish | 0.66 (0.12–3.73) | .641 | 3.39 (0.62–18.52) | .158 |

| Other | 1.51 (0.50–4.57) | .465 | 2.68 (0.94–7.62) | .065 |

| Family language: non-English vs. English | 0.34 (0.06–1.95) | .226 | 0.29 (0.06–1.44) | .131 |

| Family race (reference = White) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.75 (0.27–2.13) | .592 | 2.43 (0.92–6.45) | .074 |

| Hispanic | 0.48 (0.12–1.89) | .294 | 1.20 (0.36–4.04) | .769 |

| Other | 0.18 (0.02–1.85) | .149 | 0.55 (0.12–2.49) | .439 |

| Family education level: some college vs. high school or less | 0.54 (0.26–1.10) | .089 | 0.82 (0.47–1.45) | .502 |

| Relationship to patient: not spouse/partner vs. all other | 1.69 (0.83–3.45) | .149 | 1.75 (0.98–3.13) | .057 |

| Family visited every day vs. at least once but not every day | 1.64 (0.81–3.32) | .167 | 2.90 (1.62–5.20) | <.001 |

| Site (reference = site A) | ||||

| B | 0.36 (0.09–1.49) | .157 | 10.87 (3.15–37.43) | <.001 |

| C | 3.46 (0.77–15.52) | .105 | 1.58 (0.40–6.31) | .514 |

CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

To make the Table of our regression analysis results less complex and more readable, we dropped from the models (at the end) some variables that were highly nonsignificant in all the models. To prevent collinearity, we also excluded from the models patient variables that were clearly redundant with family variables, such as race and religion. We screened all variables for collinearity;

Table shows performance on all nine care processes in the Care and Communication Bundle. Table also shows results from the multiple variable analyses of predictors of five of the care processes. As explained in the text, we excluded from this analysis the distribution of a family information leaflet because the leaflet was not available at two sites when the study began. We also did not include the measures related to pain assessment and management because sites in the study were involved in national efforts, unrelated to our research, to increase monitoring and treatment of pain, as mandated by the Joint Commission. Finally, we were unable to estimate the relationship of the predictors to offer of spiritual support because site almost perfectly predicted whether spiritual support was offered;

we treated patient age (range, 22–102), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score (range, 7–48), Charlson Index (range, 0–15), and ICU length of stay (range, 2–126) as continuous variables.

Identification of a medical decision-maker was less likely for patients with Hispanic families than for those with white families, and more likely when family visited daily and when the patient had higher comorbidity (Table 3). Investigation for an advance directive was more likely for patients with non-English-speaking families, but was less likely for those with Hispanic families compared to those with non-Hispanic white families. Investigation of resuscitation preference was more likely for older patients and those receiving daily family visits. It was less likely for those with Jewish families compared to patients with Protestant families. Performance of family meetings was not associated with any patient or family factors except chronic comorbidity. An offer of social work support was more likely for male patients, those with higher comorbidity burden, and those whose families visited daily.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study in diverse ICUs at three hospitals in different parts of the country, we found that performance of evidence-based care processes that providers, patients, and their families endorse as essential components of high-quality ICU palliative care was inconsistent and infrequent. Interdisciplinary family meetings to discuss goals of care in relation to the patient’s condition, prognosis, and preferences were documented for <20% of patients as late as 5 days after admission to the ICU for critical care treatment. Information in printed form was rarely distributed to families, despite evidence from two randomized, controlled, multicentered trials demonstrating the effectiveness of this low-cost approach (14, 15). Assessment and management of pain were more consistently and frequently performed for patients in this study.

Our cohort included >500 patients receiving intensive care for medical or surgical illness for at least 5 days and >300 of their family members. The study included large urban academic hospitals and smaller community hospitals and ICUs of diverse size, case mix, and care models. At each of these sites, we identified important opportunities for improvement in the quality of palliative care provided to critically ill patients and their families, as measured by the Care and Communication Bundle of core ICU processes (9, 10). We also found that selected characteristics of patients and of families, and the site where they received care, were associated with variations in care process performance. These findings may help in development of targeted interventions to improve ICU palliative care.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective multisite study to evaluate performance directly, formally, and systematically on validated measures addressing multiple domains of ICU palliative care quality. We previously described development of this set of measures including pilot and feasibility testing through informal review of medical records by clinical nurses for a small purposive sample of patients from each of a different group of ICUs across the country that had also participated in other ways in developing the measures (9). Documentation of some of these processes was part of the data collection for a multicentered trial testing an intervention to improve care for patients who died in ICUs in ten hospitals in the state of Washington; those processes were abstracted from medical records along with a long list of other variables being evaluated as potential predictors of the Quality of Dying and Death (16) rated by bereaved families (17). In the present study, we focused specifically on performance of all care processes in the Care and Communication Bundle for a large consecutive cohort of all patients in the study ICUs for at least 5 days, regardless of the patient’s vital status at discharge. We used detailed specifications posted by the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. In addition, we conducted multivariable regression analyses to identify predictors of performance of five of these care processes. Ho et al (20) compared overall ratings by physicians and nurses of the quality of palliative care in ICUs in a convenience sample of 13 hospitals; these ratings assessed care in the ICU generally rather than care of any specific patient.

In our analyses, the risk of death (as measured by Charlson comorbidity index) emerged as the most consistent predictor of ICU palliative care process performance. This may reflect appreciation on the part of critical care clinicians at these sites of the special importance of providing high-quality palliative care for acutely ill patients with the heaviest burden of chronic illness. It may also be a reflection of clearer and stronger expression of need for this care by the patients or families themselves. Whereas palliative care is certainly appropriate when acute illness is superimposed on multiple chronic comorbid conditions, there is a broader mandate to integrate palliative care for all ICU patients and their families, as expressed by the Institute of Medicine (1), by all societies representing critical care professionals (2–4, 19) and by large national hospital organizations. Our data demonstrating low overall levels of performance of key palliative care processes for patients treated for at least 5 days in ICUs suggest that important opportunities to improve palliative care exist for patients at high risk for hospital death or other unfavorable outcomes.

Our analyses also suggest an association between family race/ethnicity and performance of several ICU palliative care processes, including identification of a medical decision-maker and investigation for an advance directive. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that Hispanic patients may be less likely to prepare an advance directive (20). This may have discouraged ICU clinicians from inquiring whether such patients had previously expressed their preferences for intensive care treatments. In addition, clinicians may have been deterred by the challenges of cross-cultural discussions. Because some patients, including patients from Hispanic families, do express their preferences in advance, and because the majority of patients cannot participate personally in communication or decision-making about their care during severe critical illness, it remains important for clinicians to make every effort to determine without delay whether an advance directive exists for each patient and, if so, what it provides. Investigation for an advance directive helps focus attention on the values, goals, and preferences of the patient and can serve to open or continue an ongoing dialogue with the family about appropriate goals of care (21, 22). Emotional and practical stresses are a universal problem for ICU families across diverse backgrounds (7, 23, 24). Thus, an offer of social work support, as defined in the Care and Communication Bundle, is a routine component of high-quality ICU palliative care (7, 10). Open visitation for ICU families has gained increasing support within the critical care community (19, 25, 26) and is strongly advocated not only by families but also by patients (7). The association we found between daily family visits and performance of core palliative care processes provides support for liberal approaches to visiting.

The “bundle” strategy used in this study has gained wide acceptance as a valuable method for measuring and improving quality in a variety of ICU practice areas (27–29). With this strategy, measures of processes that individually improve care in a particular clinical area are applied together for greater impact (27, 29). Bundles are used to implement best practices for prophylaxis against catheter-related bloodstream infection (30. 31) and for management of ICU patients with sepsis. Although the Care and Communication Bundle, like other ICU bundles, is composed of care process rather than outcome measures, these care processes address established domains of ICU palliative care quality (6) and the processes themselves have been specifically endorsed as important by ICU clinicians, patients, and families (7, 9). By focusing on performance of measures in this Care and Communication Bundle, we sought an approach that would be well-aligned with current efforts to improve the quality of other aspects of ICU care while evaluating the timeliness, reliability, and consistency of ICU palliative care process performance.

In this study, we evaluated performance of care processes but did not implement an intervention to improve performance. Measurement is essential for quality improvement, identifying opportunities, recognizing accountability, and allowing comparison of results of an improvement effort with baseline (or benchmark) performance. However, although measurement may also help to trigger clinical activities that are targets of such an effort, it does not ensure that performance will improve. To improve quality in any area, including palliative care, an intervention including attention to work systems is needed (32). Improvement also depends on engagement of various disciplines collaboratively to anticipate challenges, develop strategies, strengthen teamwork, and thereby achieve goals of high-quality care. In addition, results of ongoing assessment should be provided to clinicians as performance feedback, together with structured discussion of steps to improve care. The dramatic success of the Michigan Keystone Project (31) and others to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections has encouraged efforts by groups of ICUs to improve palliative care using similar methods, including several initiatives based in whole or in part on measures in the Care and Communication Bundle (33, 34). Preliminary results indicate that these efforts have been effective in improving performance of palliative care processes in the bundle (33, 34). The IPAL-ICU Project (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU) Project, a Web-based resource sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and the Center to Advance Palliative Care (35), provides expert guidance, tools, and other materials to promote the success of such interventions.

This study has several limitations. First, practice in the ICUs we sampled in three hospitals may not be representative of that in other ICUs and hospitals across the United States. These ICUs, however, were selected for their diversity in geographic location, hospital size, ICU care model, and case mix, and our patient and family cohorts were large and heterogeneous. Second, the source of data on performance of care processes was medical record (paper charts and electronic records) review rather than direct observation of practice. Although it is possible that processes of care were performed but not documented, medical record documentation provides the most practical and feasible source of data for routine monitoring, feedback, and improvement of ICU care. The Care and Communication Bundle focuses on aspects of practice such as determination of resuscitation status, investigation for an advance directive, and clinicians’ discussions with the family about goals of care that could be routinely included in chart documentation. In addition, the medical record is a key mechanism for communication among clinicians, helping to coordinate activities of multiple caregivers and ensuring that each is aware of key processes that have and have not been performed by various clinicians. Third, we did not measure some specific characteristics of the sites. The data suggest that unmeasured site characteristics do influence performance of care processes and deserve further study. Finally, our purpose here was to describe the prevalence and predictors of ICU performance of certain palliative care processes, not to evaluate associations between these processes and outcomes of care, such as family satisfaction or well-being. Measuring the relationship between care processes and such outcomes is an important additional step.

CONCLUSIONS

The essential domains of high-quality ICU palliative care have been clearly defined. They also have been operationalized and specified as process measures of care for use in routine evaluation and improvement of clinical performance. In this study, we found that performance on these particular evidence-based measures was lacking across a diverse group of ICUs, indicating important opportunities for improvement. Given the mandate to improve the quality of ICU care including palliative care for all critically ill patients and their families, available resources and effective strategies for performance improvement should be broadly and fully utilized. Methods used to improve the quality and safety of other aspects of ICU care, including emphasis on efficient work systems, practical tools, and interdisciplinary teamwork, show promise for ensuring delivery of high-quality palliative care in the ICU.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by R21 AG029955 from the National Institute on Aging. During the period of this work, Dr. Nelson was supported by a K02 Independent Scientist Research Career Development Award AG024476, followed by a K07 Academic Career Leadership Award, AG034234, both from the National Institute on Aging. Additional support was provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service (grant REA-08-260). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Work was performed at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY; James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD; University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; Norman Regional Medical Center, Norman, OK.

Dr. Nelson consulted for the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc. and Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Puntillo consulted for Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press (Institute of Medicine); 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selecky PA, Eliasson CA, Hall RI, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with cardiopulmonary diseases: American College of Chest Physicians position statement. Chest. 2005;128:3599–3610. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Accessed July 1, 2011];National Priorities Partnership website. Available at: http://www.nationalprioritiespartnership.org/Priorities.aspx.

- 6.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson JE, Puntillo KA, Pronovost PJ, et al. In their own words: Patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:808–818. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181c5887c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson JE, Boss RD, Brasel KJ, et al. [Accessed July 1, 2011];Defining standards for ICU palliative care: A brief review from The IPAL-ICU Project. 2010 Available at: http://www.capc.org/ipal-icu/monographs-and-publications/ipal-icu-defining-standards-for-icu-palliative-care.pdf.

- 9.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, et al. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: A practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:264–271. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed July 1, 2011];National Quality Measures Clearinghouse Web site. Available at: http://qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/

- 11.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;311:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy CR, Ely EW, Payne K, et al. Quality of dying and death in two medical ICUs: Perceptions of family and clinicians. Chest. 2005;127:175–183. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1138–1146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho LA, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, et al. Comparing clinician ratings of the quality of palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:975–983. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a91db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: Impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4131–4137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo B, Steinbrook R. Resuscitating advance directives. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1501–1506. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: Ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Philippart F, Timsit JF, et al. Perceptions of a 24-hour visiting policy in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:30–35. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295310.29099.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berwick DM, Kotagal M. Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: Time to change. JAMA. 2004;292:736–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resar R, Pronovost P, Harraden C, et al. Using a bundle approach to improve ventilator care processes and reduce ventilatorassociated pneumonia. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berenholtz SM, Milanovich S, Faircloth A, et al. Improving care for the ventilated patient. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy MM, Pronovost PJ, Dellinger RP, et al. Sepsis change bundles: Converting guidelines into meaningful change in behavior and clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:S595–S597. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000147016.53607.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Ngo K, et al. Developing and pilot testing quality indicators in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2003;18:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: A model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cornell M, McNicoll L, Martin E, et al. Improving palliative care in RI ICUs: A model for success. Poster presentation, Center to Advance Palliative Care National Seminar; Phoenix, AZ. October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. [Accessed July 1, 2011];ICU Palliative Care Toolkit. Available at: http://qualitypartnersri.org/cfmodules/objmgr.cfm?Obj-Hos_Clinical_Palliative&pmid-90&mid-117cid-1776&clearyes-bc-Palliative_Care&bcl-3.

- 35. [Accessed July 1, 2011];The IPAL-ICU Project. Available at: http://www.capc.org/ipal-icu/