Abstract

Background/Aims

Liver fibrosis is associated with angiogenesis and leads to portal hypertension. Certain antibiotics reduce complications of liver failure in humans, however, effect of antibiotics on the pathologic alterations of the disease are not fully understood. The aim of this study was to test whether the non-absorbable antibiotic rifaximin could attenuate fibrosis progression and portal hypertension in vivo, and explore potential mechanisms in vitro.

Methods

Effect of rifaximin on portal pressure, fibrosis, and angiogenesis was examined in wild type and toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) mutant mice after bile duct ligation (BDL). In vitro studies were carried out to evaluate the effect of the bacterial product and TLR agonist, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on paracrine interactions between hepatic stellate cells (HSC) and liver endothelial cells (LEC) that lead to fibrosis and portal hypertension.

Results

Portal pressure, fibrosis, and angiogenesis were significantly lower in BDL mice receiving rifaximin compared to BDL mice receiving vehicle. Studies in TLR4 mutant mice confirmed that the effect of rifaximin was dependent on LPS/TLR4 pathway. Fibronectin (FN) was increased in BDL liver and was reduced by rifaximin administration and thus was explored further in vitro as a potential mediator of paracrine interactions of HSC and LEC. In vitro, LPS promoted FN production from HSC. Furthermore, HSC-derived FN promoted LEC migration and angiogenesis.

Conclusion

These studies expand our understanding of the relationship of intestinal microbiota with fibrosis development by identifying FN as a TLR4 dependent mediator of the matrix and vascular changes that characterize cirrhosis.

Keywords: intestinal decontamination, lipopolysaccharide, toll like receptor-4, fibronectin, liver, angiogenesis, liver, fibrosis, rifaximin

Introduction

Intestinal bacteria and their byproducts contribute to infectious complications of chronic liver disease in humans such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis [1]. Current concepts postulate that this occurs by virtue of increased epithelial barrier permeability that allows bacteria from the intestinal lumen to enter mesenteric lymph nodes, the portal circulation, and peritoneum, termed bacterial translocation [2, 3]. Furthermore, delivery of bacterial products to the portal circulation may also underlie the process of liver injury and fibrosis progression [4–6]. Though the molecular mechanisms by which intestinal bacteria achieve these effects is not precisely understood, a current paradigm identifies bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as an activating ligand for hepatic toll like receptor-4 (TLR4), an important constituent of the innate immune system [5]. However, since every major cell type in the liver expresses TLR4, the relative contributions of different TLR4-positive liver cell populations to cirrhosis progression requires additional investigation [4, 7, 8].

Development of liver fibrosis is temporally and spatially linked with angiogenesis and vascular remodeling of the hepatic sinusoids [9, 10]. Although the complex interplay is not fully understood, these associated phenomena contribute to cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Therefore, increasing attention is being directed towards the interactions of liver endothelial cells (LEC) with the more traditional cell implicated in liver fibrosis, the hepatic stellate cell (HSC) [11]. Previous studies in our lab showed that the TLR4 pathway in LEC regulates liver angiogenesis through its effector protein MyD88 and promotes the development of fibrosis associated angiogenesis [12]. Recent work has also implicated TLR4 expressed on HSC as a key driver of liver fibrosis owing to stimulatory effects of TLR4 activation on the TGF-β pathway [13]. Other recent studies have highlighted the importance of soluble paracrine factors such as angiopoietin-1 between these two cell types in the development of fibrosis [11, 14]. In addition to soluble molecules, the early matrix microenvironment of fibrosis could also regulate the interaction between HSC and LEC to perpetuate liver fibrosis and its associated vascular changes. We hypothesized that fibronectin (FN), which is a protein that is secreted early in the process of liver injury and which is implicated in both LEC angiogenesis [14] as well as HSC activation [15], could play a key role in mediating crosstalk between these cell types in response to TLR4 activation.

In this study, we tested the effect of rifaximin, a potent intestinal decontaminant recently approved for treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in human liver disease [16], on the progression of liver fibrosis. Furthermore, we explored the mechanistic links of TLR4 signaling between HSC and LEC in the context of the fibrotic liver microenvironment. Our results show that in a murine model of bile duct ligation (BDL) induced liver fibrosis, rifaximin administration leads to less fibrosis, angiogenesis, and portal hypertension. Furthermore, we identify FN, as an early matrix molecule that links TLR4 activation of HSC with LEC based angiogenesis, thereby identifying a paracrine matrix factor as an instigator for development of cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animal procedures

C57Bl/6, C3H/HeOuJ [TLR4–wild-type (WT)] mice and C3H/HeJ [TLR4-mutant (MT)] mice, which carry a spontaneous mutation that confers a loss of TLR4 function, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories [12] (Bar Harbor, ME). BDL and sham surgery was performed as previously described [17]. Vehicle (PBS with 0.2% SDS) or rifaximin (50 mg/kg, kindly provided by Salix Pharmaceuticals) was administered daily by gavage for three weeks starting after surgery. All procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell culture and siRNA transfection

Human HSC (ScienCell [14]) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Human LEC (ScienCell [14]) were cultured in endothelial cell culture medium (ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics and 10% endothelial cell growth supplement. Transfection of FN-siRNA or control siRNA in HSC was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol using 10 nM siRNA (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Portal pressure measurements

Portal pressure was directly measured using a digital blood pressure analyzer (Digi-Med) with a computer interface [17]. Once the analyzer was calibrated, a 16-gauge catheter attached to the pressure transducer was inserted into the portal vein and sutured in place. The pressure was continuously monitored, and the average portal pressure was recorded. Upon sacrifice of the animal, the spleen was removed and weighed and spleen/body weight ratio was calculated.

Serum and stool analyses

Serum was collected from whole blood from each animal at time of sacrifice and transferred into 3.5 ml serum separating tubes. Specimens were processed and analyzed for serum transaminases and bilirubin levels by the Mayo Clinic Special Studies Laboratory, a clinically validated reference laboratory. Serum levels of LPS binding protein (LPSBP) were determined using a sandwich ELISA (Abnova Corporation), as recommended by the manufacturer instructions. Analyses of all samples, standards and controls were performed in triplicate. LPS measurements from mouse serum were carried out by Charles River Laboratories using kinetic turbidimetric LAL method [18, 19]. Fresh stool specimens were collected from mice 3 weeks after BDL or sham and rifaximin or vehicle and analyzed for aerobic and anaerobic stool culture as previously described [20].

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

Frozen liver sections were fixed with ice-cold acetone and blocked with 10% goat serum or 10% bovine serum for 2 hours at room temperature to eliminate nonspecific background. Tissue sections were then incubated with primary antibodies against von Willebrand factor (vWF; Sigma; 1:400), FN (BD Transduction Laboratories; 1:300), neuropilin-1 (R&D Systems; 1:80) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFR, Cell Signalling; 1:100) at 4°C overnight. This was followed by incubation with appropriate Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with TOTO-3 stain. Immunofluorescent staining was visualized with a Zeiss LSM Pascal Axiovert confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss), and images from vWF, FN, PDGFR and neuropilin-1 staining were quantified with Metamorph software (version 7.6, Molecular Devices, United States). For quantification, 5 images were randomly selected for quantification analysis from each sample and the software program quantified the staining intensity of the selected images based on a preselected threshold. Confocal microscopic image quantification of fibrosis was also carried out with Sirius red staining of frozen as well as paraffin embedded tissue sections as previously described [12].

Generation of HSC-derived matrix

HSC extracellular matrix devoid of cells was prepared according to a modified protocol reported by Jarnagin [21]. Briefly, HSC were seeded and grown to confluency for 7 to 10 days. Subsequently, the cells were depleted from the extracellular matrix by incubating with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate in Dulbecco’s PBS at room temperature until cells detached and could be removed by gentle washing with PBS. The decellularized HSC derived matrix was then used for culturing of LEC as described in individual experiments.

In vitro tubulogenesis assay with LEC

Human LEC (P3–5) were serum starved overnight, then seeded on growth factor reduced Matrigel (2×104 cells/4-well chamber slide) in basal DMEM for up to 10 hours after which tubulogenesis was visualized and photographs were taken using an inverted microscope. Images were quantified using Image Pro Software. To evaluate the effect of FN on tube formation in vitro, FN neutralizing antibody (20 μg/ml; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) was applied at the time that cells were seeded on Matrigel. LEC were also cultured on HSC derived decellularized matrix in some tubulogenesis experiments as indicated.

LEC migration assays

Single cell motility was measured using time lapse video microscope, and collective cell migration was investigated using a Boyden chamber assay [22]. Briefly, LEC were serum starved overnight then plated on non-coated or FN-coated dishes (5 μg/mL, BD Biosciences) in basal medium. Single cell motility was recorded by time-lapse video microscopy using a Zeiss LSM510 system with a temperature controller [22]. For quantitative evaluation of total distance traveled, migration tracks of 20 individual cells from 4 independent experiments were analyzed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging Corp, West Chester, PA). Chemotactic cell migration was evaluated using Boyden chamber assay, with 50 μg/mL FN, or PBS vehicle, in the bottom chamber. Cells migrating to the bottom surface of the membrane were visualized using DAPI nuclear staining. Migrated cells from 6 fields in each of 3 independent experiments were compiled.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Data analysis was performed using JMP-8 software. For paired and normally-distributed data, statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed student’s t-tests. For normally-distributed multiple comparisons, statistical analyses were performed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey post test. Stool culture results were not normally distributed and were therefore analyzed by Kruskal Wallis non-parametric analysis. For all analyses, a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Rifaximin attenuates BDL induced fibrosis and associated vascular changes

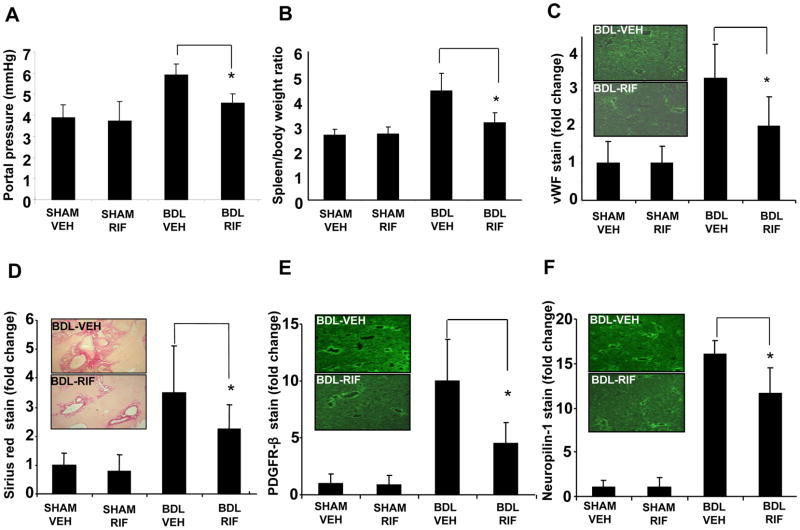

In order to study the effect of intestinal decontamination on fibrosis and vascular parameters associated with cirrhosis, we used the BDL model to induce liver fibrosis, then gavaged the mice with the nonabsorbable antibiotic, rifaximin, or vehicle for a duration of three weeks after surgery. While portal pressure was elevated in mice after BDL, this increase was significantly attenuated in BDL mice receiving rifaximin (Figure 1A). Spleen/body weight ratio measurements also corroborated the results of the direct portal pressure measurement analysis (Figure 1B). Rifaximin concurrently attenuated BDL induced angiogenesis as evidenced by attenuated vWF staining of tissues (Figure 1C, Suppl. Figure 1A), indicating that rifaximin prevents the angiogenesis and portal hypertension changes that accompany liver fibrosis.

Fig. 1. Rifaximin attenuates BDL induced fibrosis and associated vascular changes.

Mice underwent sham or BDL surgery and received rifaximin (50 mg/kg x3weeks) or vehicle for 3 weeks. (A) Portal pressure in BDL rifaximin group was significantly lower than BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=5). (B) Spleen/body weight ratio in BDL rifaximin group was significantly lower than BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=12). (C) vWF positive endothelial cell staining in BDL rifaximin group liver sections was significantly less than BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=6). (D–F) Sirius red stain for collagen, and PDGFR-β and neuropilin-1 positive activated HSC staining was lower in rifaximin BDL group compared to BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=7; right panel-representative images from BDL groups are depicted with graphic quantitation-see Supplementary Figure 1 for representative images from all 4 groups). BDL-bile duct ligation, VEH-Vehicle, RIF-rifaximin.

To assess whether improvements in portal pressure and angiogenesis correspond with improved fibrosis, we analyzed mice from the different experimental groups for several complementary histological markers of fibrosis and HSC activation. Rifaximin attenuated the BDL induced increase in Sirius red staining (Figure 1D, Suppl. Figure 1B). Markers of HSC activation, PDGFR-β (Figure 1E, Suppl. Figure 1C) and neuropilin-1 [22] (Figure 1F, Suppl. Figure 1D) were similarly attenuated. Animals receiving rifaximin also showed attenuated increase in AST and ALT after BDL although the effect was not statistically significant (Suppl. Figure 2A and B). Together, these data indicate that rifaximin attenuates myofibroblastic activation of HSC during BDL induced liver injury.

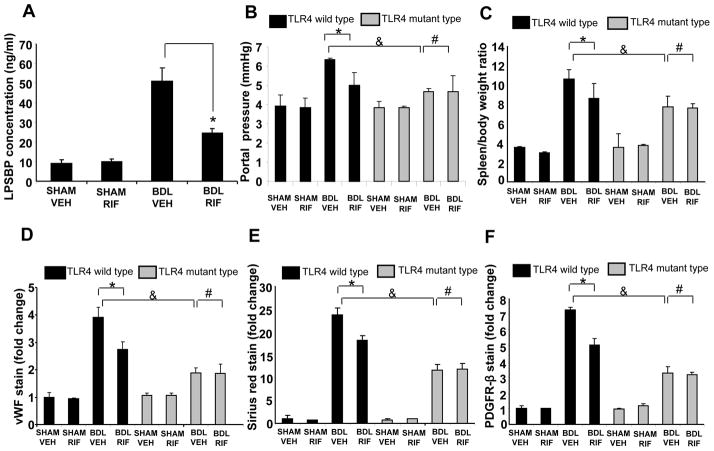

LPS-TLR4 pathway is responsible for the attenuating effect of rifaximin on liver fibrosis, angiogenesis, and portal hypertension

Since TLR4 is the canonical receptor for LPS, we next addressed the question of whether the TLR4 pathway is involved in rifaximin induced attenuation of liver fibrosis and angiogenesis. First, we evaluated serum levels of LPS and LPSBP, a surrogate marker of LPS-TLR4 activation [23]. While we were unable to show an increase in LPS levels at the single time point at animal sacrifice (0.47±0.05 EU/mL in sham-vehicle, 0.36±0.04 EU/mL in BDL-vehicle, and 0.34±0.04 EU/mL in BDL-rifaximin; n=4–6 samples per group), as shown in Figure 2A, LPSBP levels were elevated after BDL and the BDL-induced increase in serum LPSBP was significantly blunted in animals receiving rifaximin. Furthermore, both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial counts from stool were increased after BDL and the BDL-induced increase was significantly reduced in animals receiving rifaximin (Suppl. Figure 3). We next directly evaluated the role of TLR4 by assessing the effect of rifaximin on liver fibrosis in TLR4 mutant mice after BDL. The results in TLR4 wild-type mice were similar to the previous experiments conducted in C57Bl/6 mice in which rifaximin significantly attenuated liver fibrosis, angiogenesis, and the portal hypertension after BDL (black bars in Figure 2B–F). Interestingly, TLR4 mutant mice showed a reduction in portal hypertension, angiogenesis, fibrosis and HSC activation even without rifaximin, consistent with prior studies (the gray bars in Figure 2B–F) [12, 13]. Furthermore, there was no further decrease in these parameters conferred by rifaximin in TLR4 mutant mice (bar 8 vs bar 7 in Figure 2B–F), supporting the concept that the beneficial effect of rifaximin on fibrosis is mediated by TLR4. Indeed, the TLR4 mutant mice showed comparable and in some cases, less fibrosis, angiogenesis, and portal hypertension after BDL than wild type BDL mice who received rifaximin (bar 7 vs bar 4 in Figure 2B–F). Together, these data indicate that LPS-TLR4 pathway mediates the rifaximin induced attenuation of liver fibrosis and angiogenesis.

Fig. 2. LPS-TLR4 pathway is responsible for the attenuating effect of rifaximin on liver fibrosis, angiogenesis, and portal hypertension.

(A) Serum LPSBP levels were measured by ELISA. LPSBP levels were significantly lower in BDL-Rifaximin group compared to BDL-Vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=7). (B) TLR4 mutant mice or strain specific wild type mice underwent sham or BDL surgery and received rifaximin (50 mg/kg x3weeks) or vehicle for 3 weeks. Portal pressure in BDL rifaximin wild type mice was significantly lower than BDL vehicle wild type mice (*p<0.05, N=5). Portal pressure in TLR4 mutant BDL mice was significantly lower than wild type BDL mice (&p<0.05, N=5). Rifaximin administration did not further reduce portal pressure in TLR4 mutant BDL mice (#p>0.05, N=5) (C) Spleen/body weight ratio in BDL rifaximin wild type mice was significantly lower than BDL vehicle wild type mice (*p<0.05, N=7). Spleen body weight ratio in TLR4 mutant BDL mice was significantly lower than wild type BDL mice (&p<0.05, N=7). Rifaximin administration did not further reduce spleen body weight ratio in TLR4 mutant BDL mice (#p>0.05, N=7). (D–F) vWF stain for endothelial cells, Sirius red stain for collagen, and PDGFR-β stain for HSC activation was lower in rifaximin BDL group compared to BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=8). Staining for vWF, Sirius red, and PDGFR- β in TLR4 mutant BDL mice was significantly lower than wild type BDL mice (&p<0.05, N=8). Rifaximin administration did not further reduce staining parameters in TLR4 mutant BDL mice (#p>0.05, N=8). BDL-bile duct ligation, VEH-Vehicle, RIF-rifaximin.

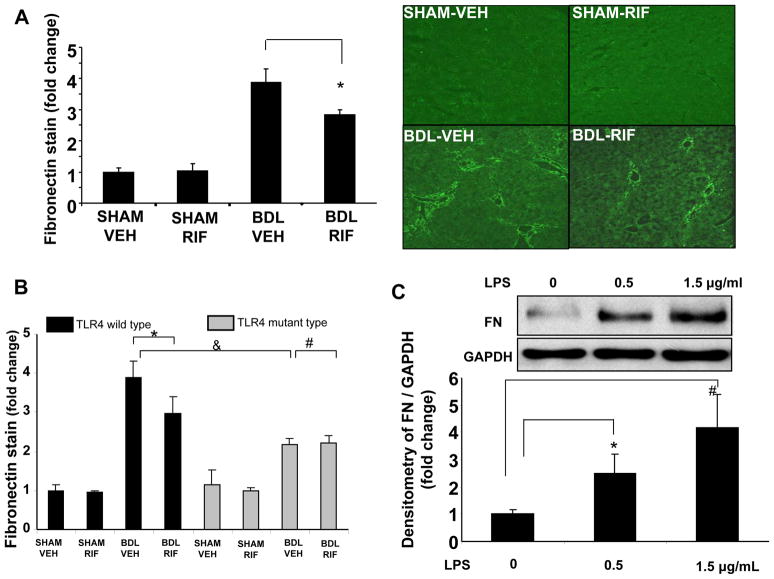

LPS-TLR4 pathway regulates FN production in HSC

Since TLR4 is expressed on both LEC and HSC [5], and both cells are important for fibrosis and its associated vascular changes, we next sought to better understand how these two cell types may communicate in response to LPS stimulation. We focused our initial attention to FN as a potential candidate since it is a critical matrix component that is involved in the early steps of the fibrotic response [14, 15]. Upon examination of liver tissues from BDL mice receiving rifaximin and vehicle, it was apparent that FN production was increased in mice after BDL and that this increase was attenuated in mice receiving rifaximin (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the BDL induced increase in FN was also attenuated in TLR4 mutant mice (Figure 3B). Therefore, we next evaluated the effects of LPS on FN production from HSC in vitro since LPS is known to potentiate production of other HSC matrix proteins [13]. Indeed, LPS stimulated FN production in HSC in a concentration dependent manner (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3. LPS-TLR4 pathway regulates FN production in HSC.

(A) FN production was lower in rifaximin BDL group compared to BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=8; right panel-representative images and left panel-graphic quantitation). (B) FN stain was lower in rifaximin BDL group compared to BDL vehicle group (*p<0.05, N=8). FN staining in TLR4 mutant BDL mice was significantly lower than wild type BDL mice (&p<0.05, N=8). Rifaximin administration did not further reduce FN staining in TLR4 mutant BDL mice (#p>0.05, N=8). (C) LPS (0–1.5 μg/mL) increases FN production in HSC in a concentration dependent manner as assessed by Western blotting (*p<0.05, N=3; #p<0.05, N=3, representative blot and densitometric quantification from multiple experiments is depicted). BDL-bile duct ligation, VEH-Vehicle, RIF-rifaximin

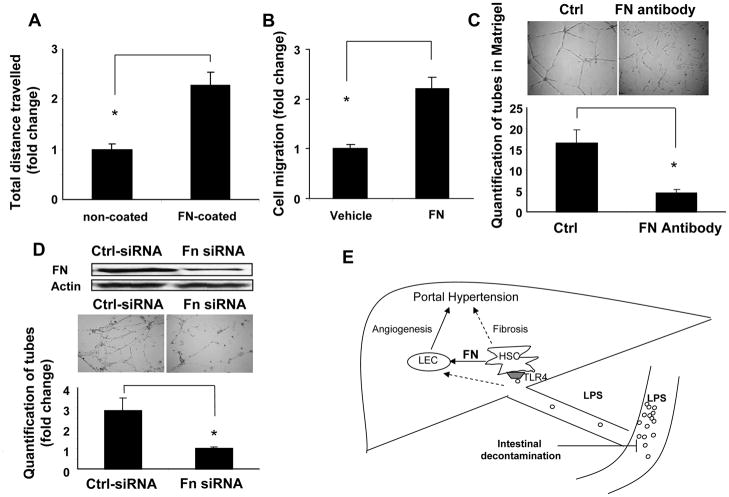

HSC derived FN promotes LEC migration and tubulogenesis

Since LPS promotes HSC mediated FN production through TLR4, further experiments were carried out to evaluate the effects of HSC derived FN on LEC angiogenic characteristics in vitro including cell migration which is a key step for angiogenesis. Chemokinetic single cell migration, evaluated by time-lapse real time video microscopy, and chemotactic cell migration, using Boyden chamber, were evaluated when LEC were exposed to FN. The results showed that the travel distance of LEC on FN-coated surface was 2-fold greater compared to LEC residing on a non-coated surface (Figure 4A). Furthermore, there was a 2-fold increase in LEC migration toward a FN gradient in Boyden assays compared to LEC migrating towards vehicle (Figure 4B). To further confirm the role of FN in tubulogenesis of LEC, we also blocked FN activity with specific FN neutralizing antibody that was added to LEC cultured on Matrigel, a substrate which is enriched in FN. LEC tubulogenesis in Matrigel was significantly inhibited by 2-fold by addition of FN neutralizing antibody as compared to control (Figure 4C). Lastly, we directly examined the effects of HSC derived FN on LEC migration and angiogenesis in the context of the fibrotic microenvironment. Thus, we utilized a “conditional matrix” model whereby LEC were cultured and studied on an HSC derived matrix [21]. In these studies, the HSC derived matrix is depleted of HSC prior to seeding of LEC thereby allowing us to focus on matrix based paracrine interactions. To directly assess the role of HSC derived FN or LEC function within the HSC conditioned matrix, we treated HSC with FN siRNA or control siRNA while they generated their matrix. Western blot confirmed FN knock-down from FN-siRNA silenced HSC (Figure 4D). Interestingly, FN enriched HSC conditioned matrix was associated with a much greater increase in tubulogenesis of LEC in the decellularized HSC derived matrix as compared to tubulogenesis of LEC in the matrix derived from HSC treated with FN siRNA (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results indicate that LPS-TLR4 induced production of FN from HSC promotes LEC tubulogenesis.

Fig. 4. HSC derived FN promotes LEC migration and tubulogenesis.

(A) Single cell motility of serum starved LEC on FN coated (5 μg/mL) vs. non-coated surface was recorded by time lapse video microscopy. The travel distance of each cell in the 4-hour video was tracked and quantified with Metamorph software. LEC traveled further on FN coated surface than non-coated surface (*p<0.05, N=3). (B) Collective cell migration was evaluated by Boyden chamber assay, with soluble FN (50 μg/mL), or vehicle in the lower well and serum starved LEC in basal medium in the upper well. Cell migration was greater in response to FN as compared to vehicle (*p<0.05, N=3). (C) Tubulogenesis of LEC in acellular conditioned extracellular matrix derived from HSC was measured. Conditioned matrices were generated from HSC pre-treated with FN siRNA (20nM) or control siRNA and cultured for 7 days. HSC were removed and LEC were seeded into the HSC derived matrices. Tube formation by LEC in the matrix was visualized at 12 hours. Tubulogenesis was diminished in LEC seeded into matrices derived from FN siRNA treated HSC compared to control siRNA treated HSC (*p<0.05, N=3). (D) Serum starved LEC were seeded in Matrigel in the presence or absence of FN antibody (20 μg/mL) in basal medium, and the tube formation was visualized at 12-hour after seeding. Tubulogenesis of LEC was attenuated by FN neutralizing antibody (*p<0.05, N=3). (E) Schematic of working model. LPS generated from intestinal microbes enters liver via portal vein. LPS stimulates FN production from HSC through TLR4. HSC derived FN in turn promotes LEC angiogenesis. Fibrosis and its associated angiogenesis lead to portal hypertension. Intestinal decontamination though rifaximin can inhibit LPS-TLR4 pathway and suppress fibrosis and angiogenesis. Dashed arrows indicate pathways previously shown that LPS can also bind to TLR4 on LEC and increase angiogenesis [12] and that LPS can bind to TLR4 on HSC and promote TGF β induced fibrosis [13].

Discussion

The intestinal microbiome is increasingly linked with a diverse array of human pathobiology including development of cirrhosis, portal hypertension and specific clinical complications [1, 4, 5, 7]. In this study, we examined the effects of a specific intestinal decontaminant, rifaximin on the development of fibrosis and its associated vascular changes of angiogenesis and portal hypertension. We demonstrate that rifaximin reduces BDL-induced liver fibrosis, portal hypertension and fibrosis associated angiogenesis. We also show that inhibition of LPS binding with its cell membrane receptor TLR4 is the mechanism for the beneficial effect of rifaximin. Mechanistic in vitro studies elucidate a key role for FN as a matrix mediator for TLR4 mediated interactions between HSC and LEC. Specifically, we identify that FN is produced in HSC in an LPS-TLR4 dependent manner and stimulates LEC angiogenesis thereby coordinating HSC-LEC angiomatrix cross-talk in fibrosis development as summarized in Figure 4E. Identification of the potential role of rifaximin as an attenuator of chronic liver disease development and progression provides clinical-translational significance to the work as well.

Current paradigms identify LPS as a ligand for TLR4 that mediates cell-type specific effects of bacterial products [5, 13]. However, a number of alternative TLR4 ligands have been identified [5] that also contribute to TLR4 activation in cirrhosis progression. As a corollary it is possible that intestinal bacteria contribute to fibrosis through TLR4 independent mechanisms as well [5, 7]. We sought to address these possibilities through our analysis of the effects of rifaximin on TLR4 mutant mice to discern if there were any additive effects of rifaximin in these mice and to compare the relative size of effect of rifaximin in the setting of mutant TLR4. The lack of additive effect of rifaximin or fibrosis prevention in TLR4 mutant mice supports the concept that rifaximin is acting through inhibition of the LPS-TLR4 pathway. In parallel, TLR4 mutant mice evidenced quantitatively similar, and in some parameters a moderately greater anti-fibrotic effect as compared to the anti-fibrotic effects of rifaximin, suggesting that TLR4 ligands other than LPS, or intestinal bacteria that are not sensitive to rifaximin, could also be contributing to fibrosis. Indeed, a number of potential candidates have emerged in the past few years including the histone protein HMGB1 and even the extra domain A of FN itself [24, 25]. Furthermore, we could not document increased LPS levels in serum of mice after BDL supporting the concept of LPS independent activation of TLR4 in our study. However, elevations in serum LPS can be technically difficult to detect and may vary substantially during the chronology after BDL [26, 27]. Therefore, other serum surrogate markers have been proposed for detection of LPS including bacterial DNA and LPSBP [23, 28]. Indeed, in our study LPSBP levels were significantly elevated in response to BDL and partially normalized by rifaximin with LPSBP levels paralled by changes in stool bacteria counts. Interestingly, rifaximin has recently been shown to have effects beyond traditional microbial growth inhibition as demonstrated by subinhibitory concentrations of the drug, that might well be absorbed, inhibiting virulence properties of bacterial pathogens [29], leading to stabilization of epithelial cells [30] and activating PXR, a nuclear receptor involved with detoxification and removal of foreign toxic substances from the intestine. Thus, although we anticipate that gut microbes are responsible for TLR4 activation in our study, such non-antimicrobial effects of rifaximin may also help explain findings in the present study.

Although collagen I is the quantitatively dominant matrix constituent in cirrhosis, FN is an early and important matrix component as well [14, 31–33]. Here, we demonstrate an important role for HSC derived FN on LEC migration and tubulogenesis, in vitro readouts that correlate with angiogenesis in vivo. Indeed, LEC migration and tubulogenesis are significantly enhanced on FN-coated substrate and in HSC derived FN enriched matrix. FN is not exclusively produced by HSC in liver and in fact, a focused microarray analysis we carried out revealed that LEC also increase FN production in response to BDL (Suppl. Table 1). Additionally, FN also amplifies HSC activation [34–36] and thus, FN could be a key contributor to fibrotic and vascular changes in cirrhosis by acting as a paracrine matrix factor.

TLR4 is expressed on multiple liver cell types including LEC, Kupffer cells, and HSC [12, 13]. Indeed, TLR4 on HSC plays a dominant role in fibrosis development through effects on TGFβ dependent collagen production [13]. Additionally, we previously showed that TLR4 directly stimulates angiogenesis during liver fibrosis in vivo [12]. While LEC play a crucial role in fibrosis associated angiogenesis, HSC are the predominant source of extracellular matrix production in the fibrotic liver [37]. In the present study, we evaluated how TLR4 activation of HSC could lead to the vascular changes of cirrhosis including angiogenesis and portal hypertension through paracrine regulation of LEC by TLR4 activated HSC. We focused particularly on how HSC derived matrix could mediate this process by using an innovative “conditioned matrix” model in which LEC phenotype could be studied on HSC derived matrix but in the absence of other potentially confounding HSC soluble factors. This model revealed the integral role of HSC derived FN for LEC angiogenesis. Thus, the present study uncovers TLR4 dependent paracrine interactions between these sinusoidal cell types that contribute importantly to angiomatrix changes associated with liver cirrhosis.

The clinical role of antibiotics in patients with chronic liver disease continues to evolve. While clinical and experimental studies document beneficial effects of antibiotics in prevention of various complications of liver cirrhosis [23, 38], this is counterbalanced by concerns pertaining to antibiotic resistance. For example, some antibiotics have been shown to reduce complications in cirrhosis and thereby improve patient survival [23]. Other antibiotics have also been shown to attenuate the progression of liver fibrosis in experimental models of fibrosis although results have varied based on the specific antibiotic that was tested [6, 38, 39]. However, antibiotic side effect and resistance remain a concern that prevents broader utilization of antibiotics in cirrhosis. In our study, we focused on the non-absorbable antibiotic rifaximin, and found that rifaximin could reduce portal pressure and fibrosis in vivo. This agent is concentrated in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby reducing the production of intestinal bacteria derived LPS with limited systemic toxicity or resistance [40]. Rifaximin is of topical interest since it is FDA approved for treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with an acceptable safety profile in patients with chronic liver disease [16, 41]. Although clearly further studies in the BDL model and in other preclinical cirrhosis models such as carbon tetrachloride are warranted to assure further generalizability of results and to determine if antibiotics such as rifaximin could also reverse existing fibrosis as compared to preventing development of fibrosis as we have shown here. Nonetheless, this study provides an important experimental basis for potential evaluation of rifaximin in patients with liver fibrosis for indications beyond its utility in hepatic encephalopathy. Concurrently, the work extends our cellular understanding of the role of FN in the parallel development of liver fibrosis and the vascular changes that accompany it.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: DK59615 (VS) and P30DK084567 Digestive Disease Center Grant

Abbreviations

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TLR4

toll like receptor-4

- LEC

liver endothelial cells

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- FN

fibronectin

- BDL

bile duct ligation

- LPSBP

lipopolysaccharide binding protein

- vWF

von Willebrand’s factor

- PDGFR–β

platelet-derived growth factor receptor–β

Footnotes

Financial disclosure:

The authors do not have a commercial or other association with pharmaceutical companies or other parties that might pose a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Riordan SM, Williams R. The intestinal flora and bacterial infection in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45(5):744–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szabo G, Bala S. Alcoholic liver disease and the gut-liver axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(11):1321–1329. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzan S, de Almeida Quadros C, de Cleva R, Zilberstein B, Cecconello I. Bacterial translocation: overview of mechanisms and clinical impact. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(4):464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(6):1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pradere JP, Troeger JS, Dapito DH, Mencin AA, Schwabe RF. Toll-like receptor 4 and hepatic fibrogenesis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(3):232–244. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez E, Such J, Chiva MT, Soriano G, Llovet T, Merce J, et al. Development of an experimental model of induced bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic rats with or without ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(6):1230–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares JB, Pimentel-Nunes P, Roncon-Albuquerque R, Leite-Moreira A. The role of lipopolysaccharide/toll-like receptor 4 signaling in chronic liver diseases. Hepatol Int. 2010;4(4):659–672. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):1043–1055. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Semela D, Iredale J, Shah VH. Sinusoidal remodeling and angiogenesis: a new function for the liver-specific pericyte? Hepatology. 2007;45(3):817–825. doi: 10.1002/hep.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thabut D, Shah V. Intrahepatic angiogenesis and sinusoidal remodeling in chronic liver disease: new targets for the treatment of portal hypertension? J Hepatol. 2010;53(5):976–980. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taura K, De Minicis S, Seki E, Hatano E, Iwaisako K, Osterreicher CH, et al. Hepatic stellate cells secrete angiopoietin 1 that induces angiogenesis in liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(5):1729–1738. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jagavelu K, Routray C, Shergill U, O’Hara SP, Faubion W, Shah VH. Endothelial cell toll-like receptor 4 regulates fibrosis-associated angiogenesis in the liver. Hepatology. 2010;52(2):590–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.23739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13(11):1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thabut D, Routray C, Lomberk G, Shergill U, Glaser K, Huebert R, et al. Complementary vascular and matrix regulatory pathways underlie the beneficial mechanism of action of sorafenib in liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hep.24427. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aziz-Seible RS, Casey CA. Fibronectin: Functional character and role in alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(20):2482–2499. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i20.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, Poordad F, Neff G, Leevy CB, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1071–1081. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semela D, Das A, Langer DA, Kang N, Leof E, Shah VH. Platelet-derived growth factor signaling through ephrin-B2 regulates hepatic vascular structure and function. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:671–679. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang JS, Kim HJ, Ryu YH, Yun CH, Chung DK, Han SH. Endotoxin contamination in commercially available pokeweed mitogen contributes to the activation of murine macrophages and human dendritic cell maturation. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13(3):309–313. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.3.309-313.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gee AP, Sumstad D, Stanson J, Watson P, Proctor J, Kadidlo D, et al. A multicenter comparison study between the Endosafe PTS rapid-release testing system and traditional methods for detecting endotoxin in cell-therapy products. Cytotherapy. 2008;10(4):427–435. doi: 10.1080/14653240802075476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DuPont HL, Jiang ZD. Influence of rifaximin treatment on the susceptibility of intestinal Gram-negative flora and enterococci. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(11):1009–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarnagin WR, Rockey DC, Koteliansky VE, Wang SS, Bissell DM. Expression of variant fibronectins in wound healing: cellular source and biological activity of the EIIIA segment in rat hepatic fibrogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(6 Pt 2):2037–2048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao S, Yaqoob U, Das A, Shergill U, Jagavelu K, Huebert RC, et al. Neuropilin-1 promotes cirrhosis of the rodent and human liver by enhancing PDGF/TGF-beta signaling in hepatic stellate cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2379–2394. doi: 10.1172/JCI41203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albillos A, de la Hera A, Gonzalez M, Moya J, Calleja J, Monserrat J, et al. Increased lipopolysaccharide binding protein in cirrhotic patients with marked immune and hemodynamic derangement. Hepatology. 2003;37(1):208–217. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamura Y, Watari M, Jerud ES, Young DW, Ishizaka ST, Rose J, et al. The extra domain A of fibronectin activates Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(13):10229–10233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gondokaryono SP, Ushio H, Niyonsaba F, Hara M, Takenaka H, Jayawardana ST, et al. The extra domain A of fibronectin stimulates murine mast cells via toll-like receptor 4. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(3):657–665. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghiselli R, Cirioni O, Giacometti A, Mocchegiani F, Orlando F, Bergnach C, et al. Effects of the antimicrobial peptide BMAP-27 in a mouse model of obstructive jaundice stimulated by lipopolysaccharide. Peptides. 2006;27(11):2592–2599. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong JY, EFS, Hiramoto K, Nishikawa M, Inoue M. Mechanism of Liver Injury during Obstructive Jaundice: Role of Nitric Oxide, Splenic Cytokines, and Intestinal Flora. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;40(3):184–193. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.40.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellot P, Garcia-Pagan JC, Frances R, Abraldes JG, Navasa M, Perez-Mateo M, et al. Bacterial DNA translocation is associated with systemic circulatory abnormalities and intrahepatic endothelial dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;52(6):2044–2052. doi: 10.1002/hep.23918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang ZD, Ke S, Dupont HL. Rifaximin-induced alteration of virulence of diarrhoea-producing Escherichia coli and Shigella sonnei. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35(3):278–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown EL, Xue Q, Jiang ZD, Xu Y, Dupont HL. Pretreatment of epithelial cells with rifaximin alters bacterial attachment and internalization profiles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):388–396. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00691-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark RA, DellaPelle P, Manseau E, Lanigan JM, Dvorak HF, Colvin RB. Blood vessel fibronectin increases in conjunction with endothelial cell proliferation and capillary ingrowth during wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;79(5):269–276. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12500076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark RA, Quinn JH, Winn HJ, Lanigan JM, Dellepella P, Colvin RB. Fibronectin is produced by blood vessels in response to injury. J Exp Med. 1982;156(2):646–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magnusson MK, Mosher DF. Fibronectin: structure, assembly, and cardiovascular implications. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(9):1363–1370. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.9.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabatelli P, Bonaldo P, Lattanzi G, Braghetta P, Bergamin N, Capanni C, et al. Collagen VI deficiency affects the organization of fibronectin in the extracellular matrix of cultured fibroblasts. Matrix Biol. 2001;20(7):475–486. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moriya K, Bae E, Honda K, Sakai K, Sakaguchi T, Tsujimoto I, et al. A Fibronectin-Independent Mechanism of Collagen Fibrillogenesis in Adult Liver Remodeling. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):1653–1663. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhan S, Chan CC, Serdar B, Rockey DC. Fibronectin stimulates endothelin-1 synthesis in rat hepatic myofibroblasts via a Src/ERK-regulated signaling pathway. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(7):2345–2355. e2341–2344. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(2):209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, Gao W, Thurman RG. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(1):218–224. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennenberg M, Trebicka J, Buecher D, Heller J, Sauerbruch T. Lack of effect of norfloxacin on hyperdynamic circulation in bile duct-ligated rats despite reduction of endothelial nitric oxide synthase function: result of unchanged vascular Rho-kinase? Liver Int. 2009;29(6):933–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DuPont HL. Biologic properties and clinical uses of rifaximin. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12(2):293–302. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.546347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bajaj JS, Riggio O. Drug therapy: rifaximin. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1484–1488. doi: 10.1002/hep.23866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.