Abstract

PURPOSE

Our goal was to test the separate and interactive effects of drinking motives and social anxiety symptoms in predicting drinking-related consumption and problems.

METHODS

Participants (N=730; 59.7% Female) were undergraduate college students who completed measures of social anxiety symptoms, drinking motives, alcohol consumption, and drinking problems.

RESULTS

Greater social anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with less alcohol consumption, and there was some evidence that greater social anxiety symptoms were also associated with greater alcohol-relevant problems. Significant interactions between social anxiety and motives indicated that a) alcohol use was most pronounced for individuals high in enhancement motives and low in social anxiety symptoms; and b) among participants low in coping motives, drinking problems were greater for individuals high (vs. low) in social anxiety symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS

More fully identifying the individual difference factors that link social anxiety symptoms with drinking outcomes is important for informing prevention and intervention approaches.

Keywords: Social Anxiety, Drinking Motives, College Students

The social demands of college coupled with easy access to alcohol places college students at an elevated risk for utilizing substances (Ham & Hope, 2005). In addition, although individuals with social anxiety consume less alcohol than their non-socially anxious peers (Ham, Zamboanga, Bacon, & Garcia, 2009; Lewis et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2006), individuals with high (vs. low) social anxiety may actually experience more adverse consequences from drinking alcohol (Buckner, Eggleston, & Schmidt, 2006; Gilles, Turk, & Fresco, 2006; Stewart, Morris, Mellings, & Komar, 2006). In other words, for the subset of college students who are socially anxious and who engage in hazardous drinking, the associated consequences of drinking may be particularly problematic.

According to Cox and Klinger (1988, 1990), drinking behavior can be conceptualized as existing along two primary dimensions—valence and source (see also Cooper, 1994). Crossing intrinsic/extrinsic motivation with positive/negative reinforcement results in four potential drinking motives: 1) coping motives, or drinking to alleviate negative affect (negative/intrinsic motivation); 2) conformity motives, or drinking to avoid being rejected socially (negative/extrinsic motivation); 3) enhancement motives, or drinking to heighten positive affect (positive/intrinsic motivation); and 4) social motives, or drinking to maximize positive social rewards (positive/extrinsic motivation).

There is some evidence that drinking motives may differentially interact with social anxiety symptoms to affect drinking behavior and outcomes. Ham, Bonin, and Hope (2007) found that for individuals high and moderate in social anxiety, higher coping motives were significantly related to greater alcohol consumption and more alcohol-relevant problems. Meanwhile, for individuals low (but not moderate or high) in social anxiety, higher enhancement motives were significantly related to greater drinking consumption. While these findings are important for understanding the relationship between social anxiety, motives, and alcohol use and problems, they fail to clarify the extent to which motives moderate the impact of social anxiety symptoms on drinking outcomes. Specifically, all elements of the interaction between social anxiety symptoms and drinking motives have not been thoroughly investigated.

The goal of the present study was to test the separate and interactive effects of social anxiety and each of four drinking motives in predicting alcohol use and alcohol-related problems in a sample of college students. We predicted that anxiety level would moderate the relationship between coping motives and drinking outcomes, such that coping motives would be more strongly related to alcohol use for individuals high (vs. low) in social anxiety symptoms (Ham et. al, 2007). In other words, we expected that drinking to alleviate negative affect (i.e., coping) would have a stronger relationship with the drinking outcomes among people who are more socially anxious (i.e., have higher negative affect to begin with). Conversely, we expected that enhancement motives (i.e., those that are extrinsic and positively reinforcing) would have a stronger relationship with drinking outcomes among participants low (vs. high) in social anxiety symptoms. We expected a similar relationship for anxiety and social motives.

Methods

Participants

Participants were enrolled prior to the start of their first year of college at one college and two universities in the Northeast, and completed an online survey one year later at the end of their first year of college. Only participants who reported they drank alcohol in the preceding 12 months (measured at the end of the first year) were included in this study (N = 730; 59.7% Female; Mean age = 18.35, SD = 0.47). Race or ethnicity in the final sample was reported as 66.2% White, 10.7% Asian, 7.0% Latino, 6.0% Black, 0.3% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 9.7% Multi-racial, and 0.1% Unknown. See Hoeppner et al. (2010) for further details on Methods.

Measures

The Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SADS; Watson & Friend, 1969) is a 28-item measure of distress and avoidance in social situations. The Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Cooper, 1994) is a 20-item scale that assesses four potential drinking motives: Coping, Conformity, Enhancement, and Social. The Graduated Frequency for Alcohol Questionnaire (Greenfield & Rogers, 1999) assessed drinking consumption; drinking frequency (number of days per month) and quantity (number of drinks per day) were derived and a composite drinking consumption variable was created by multiplying these two values. The Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) was used to measure drinking problems in the past year. Items were dichotomized and summed for a total score.

Data Analysis

The alcohol consumption variable was not distributed normally so was log transformed. A series of hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted in which social anxiety, drinking motives, and the interaction of social anxiety × drinking motives were regressed on alcohol consumption and problems separately. Separate analyses were conducted for the four motive types. Anxiety and motives measures were centered (Holmbeck, 2002). Gender was entered as a first step on all models, and alcohol consumption was entered as a second step in the drinking problem models. The main effects and interaction were entered as a final step.

Results

The four drinking motives variables were significantly correlated to one another in a positive direction. Great social anxiety was associated with more coping and conformity motives, and less enhancement motives (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Independent Variables (N = 730)

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Anxiety Disorder Scale | 7.40 | 6.45 | -- | ||||

| 2. Coping Motives | 1.70 | 0.78 | .18*** | -- | |||

| 3. Conformity Motives | 1.48 | 0.67 | .19** | .42** | -- | ||

| 4. Enhancement Motives | 2.65 | 1.09 | −11** | .41*** | .27*** | -- | |

| 5. Social Motives | 2.95 | 1.12 | .02 | .45*** | .40*** | .74*** | -- |

Note. Means and SDs for Social Anxiety and Drinking Motives for participants who reported that they drank alcohol during the past 12 months.

p < 001;

p < .01;

p < 05;

Social Anxiety and Drinking Motives Predict Drinking Consumption1

Coping Motives

Greater Social Anxiety was significantly related to less Drinking Consumption (β=−.20; t=−5.67, p<.001), and higher Coping Motives were significantly related to greater Drinking Consumption (β=.29; t=8.20, p<.001). The interaction between Social Anxiety and Coping Motives was not significant (β=−.03; t =−.92, p>.10).

Enhancement Motives

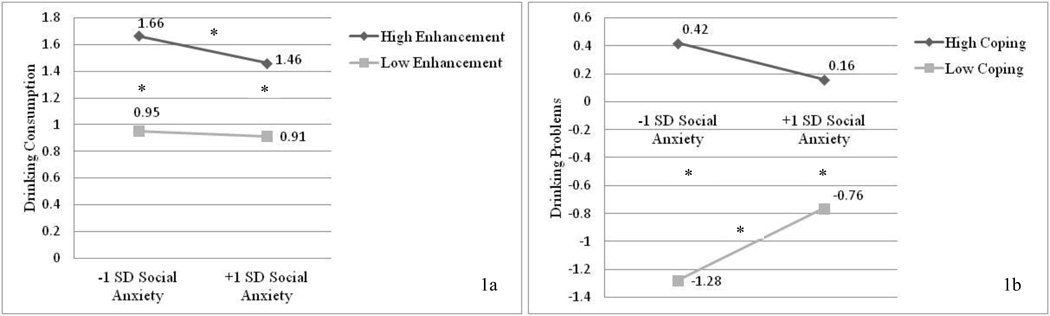

There was a significant Social Anxiety × Enhancement Motives interaction (β = −.07; t = −2.28, p < .05; Figure 1a). The simple slopes of the regression lines for individuals both High (β = 46, p < .001) and Low (β = .60, p < .001) in Social Anxiety were significant. Individuals who endorsed greater enhancement motives also endorsed greater drinking consumption. The simple slope for the High Enhancement Motives regression line was significant (β = −.17, p < .001), but the simple slope for the Low Enhancement Motives regression line was not significant (β = −.03, p > .10). When individuals had high Enhancement Motives, greater social anxiety was associated with less Drinking Consumption, but anxiety level was not relevant for those with low Enhancement Motives.

Figure 1.

a. Social Anxiety and Enhancement Motives Interact to Predict Drinking Consumption.

b. Social Anxiety and Coping Motives Interact to Predict Drinking Problems.

Social Motives

Greater Social Anxiety was significantly associated with less Drinking Consumption (β=−.16; t=−5.01, p<.01), and greater Social Motives were significantly related to more Drinking Consumption (β=.48; t=15.18, p<.001). The interaction between Social Anxiety × Social Motives was not significant (β=−.06; t=−1.96, p=.05).

Conformity Motives

Greater Social Anxiety was significantly associated with less Drinking Consumption (β=−.17; t=−4.57, p<.001). There was not a significant effect on Drinking Consumption for either Conformity Motives (β=.06; t=1.50, p>.10) or the Social Anxiety × Conformity interaction (β=.02; t=.40, p>.10).

Social Anxiety and Drinking Motives Predict Drinking Problems

Coping Motives

There was a significant Social Anxiety × Coping Motives interaction (β=−.07; t=−2.43, p<.05; Figure 1b). The simple slope for the Low Coping Motives regression line was significant (β=.08, p=.047), but the simple slope for the High Coping Motives regression line was not significant (β =−.04, p>.10). For individuals with low coping motives, drinking problems increased with greater symptoms of social anxiety. Meanwhile, the simple slopes for both the High Social Anxiety (β=.14, p<.001) and the Low Social Anxiety (β=.26, p<.001) regression lines were significant. Regardless of anxiety status, individuals drank more when they endorsed more coping motives to drink.

Enhancement Motives

The Social Anxiety × Enhancement Motives interaction was not significant (β=.01; t=.45, p>.10). Greater Social Anxiety (β=.06; t=2.04, p<.05) and greater Enhancement Motives (β=.15; t=4.67, p<.001) were associated with greater problems with drinking.

Social Motives

There was not a significant Social Anxiety × Social Motives interaction (β=−.01; t=−.47, p>.10). There was a significant main effect for Social Motives (β=.15; t=4.86, p<.001); individuals who endorsed greater social motivations to drink endorsed greater drinking-related problems. The main effect for Social Anxiety (β=.04; t=1.37, p>.10) was not significant.

Conformity Motives

There was not a significant Social Anxiety × Conformity interaction (β =−.01; t=−.40, p>.10). Greater Conformity Motives was associated with greater drinking-related problems (β=.12; t=4.20, p<.001), and the main effect for Social Anxiety was positive but did not reach significance (β=.03; t=1.03, p>.10).

Discussion

We found two significant interactions. First, as expected, we found that alcohol use was most pronounced for individuals high in enhancement motives and low in social anxiety symptoms. One interpretation is that positively reinforcing motives (e.g., enhancement) may be more strongly related to drinking among individuals low (relative to high) in social anxiety symptoms. The other significant interaction was the Coping Motives/Social Anxiety interaction in the Drinking Problems model. Contrary to hypotheses, the follow-up tests to probe this significant interaction revealed that among participants low in coping motives, drinking problems were greater for individuals high (vs. low) in social anxiety. This indicates that having a low level of affect-management motives to drink is more of a risk factor for alcohol problems if individuals also have high levels of anxiety. Although this finding appears to identify a group that might be targeted for intervention, individuals with low coping motives showed a lower level of risk than those with high coping motives. Thus, it seems unnecessary to try to identify individuals specifically who have both high anxiety and low coping motives.

Consistent with our hypotheses, individuals with greater levels of social anxiety were significantly more likely to endorse drinking motives tied to coping and conformity, and significantly less likely to endorse enhancement motives. This suggests that drinking motives that are negatively reinforcing (i.e., coping and conformity) may have greater relevance for individuals with social anxiety symptoms, as opposed to drinking motives that are positively reinforcing (i.e., enhancement and social). It could be that individuals with greater symptoms of social anxiety drink in part to reduce their anxiety, which would allow them to experience the negatively reinforcing, stress-response dampening effects of alcohol (see Ham et al., 2009). Thus, for individuals with high social anxiety, drinking problems may be especially pronounced when high (vs. low) coping motives for drinking are also endorsed.

Across all four of the Drinking Consumption models, greater symptoms of social anxiety were negatively predictive of drinking consumption. In line with prior research, individuals were significantly less likely to consume alcohol if they reported more social anxiety, even when accounting for drinking motives. Meanwhile, we found some evidence that greater social anxiety symptoms are related to more alcohol problems, in spite of being related to less alcohol consumption. Indeed, the pattern of main effects for social anxiety in the Drinking Problems model was opposite to the pattern of main effects for social anxiety in the Drinking Consumption model, although this effect only reached significance when enhancement motives were included in the model. One explanation for this finding is that because college students with social anxiety do not generally consume as much alcohol as their non-anxious peers, they lack experience with drinking. Thus, when they actually do drink in certain high-risk situations, their associated problems may be greater.

Conclusions

Findings from the present study suggest that the main effects of social anxiety symptoms and drinking motives are more influential in predicting drinking outcomes than the interaction between these two independent variables. There was also some evidence that negatively reinforcing drinking motives (i.e., coping and conformity) may be more relevant for individuals who are high in social anxiety symptoms, relative to positively reinforcing drinking motives (i.e., enhancement and social). This pattern held in most cases, except that low coping motives were actually more strongly related to drinking problems among individuals high (vs. low) in social anxiety symptoms. Nevertheless, as predicted, drinking problems reported by individuals high in social anxiety symptoms were more pronounced when participants also endorsed greater coping motives. Determining the individual difference factors that link social anxiety symptoms with drinking outcomes is important for future research efforts to inform prevention and intervention approaches for college students.

Highlights.

The main effects of social anxiety symptoms and drinking motives were more influential in predicting drinking outcomes than their interaction.

Greater social anxiety was associated with greater endorsement of coping and conformity motives, and less endorsement of enhancement motives.

Social anxiety symptoms were related to less alcohol consumption, but more drinking problems (although this later effect typically did not reach significance).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the research staff and postdoctoral fellows who assisted in this research. We are particularly grateful for the helpful feedback on this manuscript provided by Joshua Magee, Ph.D.

Role of Funding Sources

This investigation was supported in part by research grant R01AA13970 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) to the second author. This research was also supported by a T32 postdoctoral research fellowship (T32 AA07459) through NIAAA, awarded to the first author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Across all models, the model containing Social Anxiety, Drinking Motives, and the Interaction significantly enhanced the model fit above and beyond the prediction from Gender in the Consumption models, and Gender + Drinking Consumption in the Problems models (all p<.05).

Contributors

This manuscript represents a collaborative effort on behalf of Drs. Clerkin and Barnett. Both authors contributed to, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Both authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: the mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37(4):381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Klinger E. Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use: A model. In: Cox M, editor. Why people drink. New York: Gardner Press; 1990. pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles DM, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and self-efficacy as predictors of heavy drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(3):388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Who Drinks Most of the Alcohol in the U.S.? The Policy Implications. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:78–89. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Bonin M, Hope Da. The role of drinking motives in social anxiety and alcohol use. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21(8):991–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. Incorporating social anxiety into a model of college student problematic drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(1):127–150. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Bacon AK, Garcia TA. Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(3):133–145. doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27(1):87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11726683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut BA, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner BB, Stout RL, Jackson KM, Barnett NP. How good is fine-grained Timeline Follow-back data? Comparing 30-day TLFB and repeated 7-day TLFB alcohol consumption reports on the person and daily level. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Hove MC, Whiteside U, Lee CM, Kirkeby BS, Oster-Aaland L, et al. Fitting in and feeling fine: conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(1):58–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Morris E, Mellings T, Komar J. Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15:671–682. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33:448–457. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]