Abstract

Aims

Extant literature on contingency management (CM) transportability, or its transition from academia to community practice, is reviewed. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009) guides the examination of this material.

Methods

PsychInfo and Medline database searches identified 27 publications, with reviewed reference lists garnering 22 others. These 49 sources were examined according to CFIR domains of the intervention, outer setting, inner setting, clinicians, and implementation processes.

Results

Intervention characteristics were focal in 59% of the identified literature, with less frequent focus on clinicians (34%), inner setting (32%), implementation processes (18%), and outer setting (8%). As intervention characteristics, adaptability and trialability most facilitate transportability whereas non-clinical origin, perceived inefficacy or disadvantages, and costs are impediments. Clinicians with a managerial focus and greater clinic tenure and CM experience are candidates to curry organizational readiness for implementation, and combat staff disinterest or philosophical objection. A clinic’s technology comfort, staff continuity, and leadership advocacy are inner setting characteristics that prompt effective implementation. Implementation processes in successful demonstration projects include careful fiscal/logistical planning, role-specific staff engagement, practical adaptation in execution, and evaluation via fidelity-monitoring and cost-effectiveness analyses. Outer setting characteristics—like economic policies and inter-agency networking or competition—are salient, often unrecognized influences.

Conclusions

As most implementation constructs are still moving targets, CM transportability is in its infancy and warrants further scientific attention. More effective dissemination may necessitate that future research weight emphasis on external validity, and utilize models of implementation science.

Keywords: contingency management, implementation science, transportability

1. Introduction

Over a decade ago, the Institute of Medicine (1998) identified research-to-practice gaps reflecting ineffective collaboration by scientists and providers. These were thought to result from scientists too rarely addressing interests of the treatment community and providers too rarely adopting available, empirically-supported innovations. Community-based trials by the NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN; Hanson et al., 2002) or other groups (The COMBINE Study Research Group, 2003; UKATT Research Team, 2005) have intended to bridge such gaps. A target is contingency management (CM), a behavior therapy supported by extensive basic science research documenting treatment of substance misuse via operant conditioning (Higgins et al., 2008; Stitzer and Petry, 2006). Literature concerning CM efficacy is substantial, as reliably noted in meta-analyses (Dutra et al., 2008; Griffith et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006; Prendergast et al., 2006). Even so, community interest lags behind other approaches including motivational interviewing, relapse-prevention, solution-focused therapy, and 12-step facilitation (Benishek et al., 2010; Herbeck et al., 2008; McCarty et al., 2007; McGovern et al., 2004).

Historically, CM originated in methadone clinics as frequent clinic visitation allowed use of clinic privileges (e.g., take-home doses, preferred dosing times) to reinforce opiate abstinence, counseling attendance, and other adherence targets (Milby et al., 1978; Stitzer et al., 1977; Stitzer et al., 1980). Higgins and colleagues (1994; 1993) later applied CM in drug-free clinics by providing exchangeable vouchers to reinforce cocaine abstinence, an approach since widely-adapted with beneficial effects (Lussier et al., 2006). Petry’s (2000) ‘fishbowl technique’ later emerged wherein abstinence is reinforced by earning draws for prizes, with effectiveness shown in multi-site CTN trials (Peirce et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2005). More recently, efficacious CM approaches have used social reinforcement (e.g., staff recognition, status tokens) for aftercare participation (Lash et al., 2007), or wages at a ‘therapeutic workplace’ to incentivize abstinence (Silverman et al., 2007). Clearly, much thought and creativity has been applied to designing and evaluating CM methods to intervene with addiction treatment clientele.

A technology model proposes staged design, evaluation, and dissemination of behavior therapies like CM (Carroll and Onken, 2005; Rounsaville et al., 2001). The model stipulates stages for: 1) feasibility, or translation of theoretical concepts to clinical application, 2) efficacy, or quantification of therapeutic impact via comparison to waitlist/control or alternative, and 3) transportability, transition to community implementation via examination of generalizability, cost-effectiveness, relative advantage, acceptability to staff/clients, and training needs. Feasibility and efficacy criteria are well-established, but those for determining if a behavior therapy is transportable are less concrete. Model originators cite disproportionate scientific focus on feasibility and efficacy stages and insufficient attention given to transportability concerns (Carroll and Rounsaville, 2007). Indeed, this is consistent with Institute of Medicine (1998) sentiments, and suggests benefit in a structured review of CM transportability literature. To our knowledge, the current work is the first such review of this area.

To evaluate CM transportability, appreciation is needed for how aims of implementation science differ from those of efficacy research. Efficacy trial features—careful client selection, randomization, and use of highly-trained study personne—stress internal validity (Treweek and Zwarenstein, 2009). Implementation science emphasizes external validity through examination of processes whereby CM transitions from academic to community settings (Rubenstein, 2006). Fixsen and colleagues (2005) note three scenarios where poor transportability can lead to faulty conclusions of clinical ineffectiveness. These are when: 1) core therapeutic concepts are emphasized too little (or too much), leading to provider confusion about procedural aims, 2) implementation is insufficiently standardized, leading to inconsistency, and 3) the behavior therapy is mismatched conceptually or practically for the intended settings, leading to reluctant or aimless implementation. Notably, these scenarios are not mutually-exclusive.

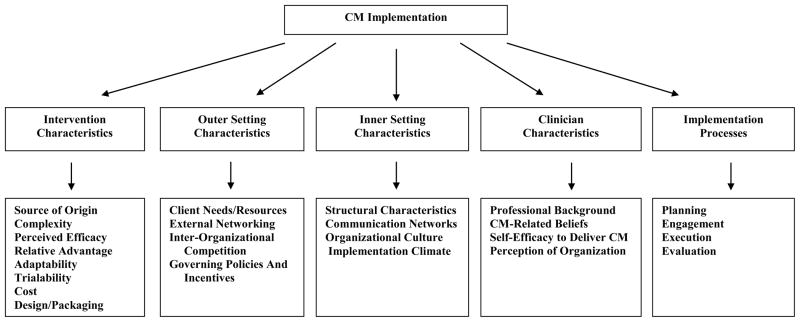

Most implementation science theories are explanatory like Roger’s (2003) Diffusion of Innovations, or prescriptive like the Addiction Technology Transfer Centers’ Change Book (2004). But the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009) offers a theoretical framework that explains and guides implementation constructs and processes. As Damschroder and Hagedorn (2011) recently applied CFIR to addiction treatment, it may inform a focused review of CM transportability. Figure 1 illustrates five CFIR domains that embody characteristics of the: 1) intervention—its source of origin, complexity, perceived efficacy, relative advantage, adaptability, trialability, cost, and packaging; 2) outer setting or socio-economic context for implementation—client needs/resources, external networking, inter-organizational competition, and governing policies; 3) inner setting or internal implementation—context structural attributes, communication networks, organizational culture, and climate; 4) clinicians—their professional background, beliefs, self-efficacy, and organizational perceptions; and 5) implementation processes—planning, engagement, execution, and evaluation. This review is structured to examine identified CM transportability literature within the CFIR framework.

Figure 1.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Applied to Contingency Management

2. Methods

2.1 Search strategy

In April 2011, publications were sought in PubMed and PsychInfo databases. The search period was 1980 to present, with further parameters that they be written in English and involve human subjects. The search strategy identified works matching search terms for CM, addiction treatment, and implementation science. CM terms were: contingency management, motivational incentives, and behavioral reinforcement. Addiction treatment terms were: substance use, substance abuse, substance dependence, substance misuse, addiction, alcoholism, smoking, addiction treatment, and substance abuse treatment. Implementation science terms were: implementation, implementation science, implementation research, dissemination, diffusion, adoption, technology transfer, translation, and training. Once appropriate, unique publications were identified, their reference lists were reviewed for additional relevant literature.

2.2 Search results

PubMed and PsychInfo searches identified 41 unique works. However, 14 of these were deemed inappropriate for the current review as: 1) efficacy studies not substantively addressing transportability (n=6), 2) studies conducted in non-addiction settings (n=6), or 3) book reviews (n=2). Review of reference lists for the remaining 27 publications garnered 22 more publications. This aggregate literature (N=49) is listed chronologically in Table 1, and consists of 33 empirical studies, 10 reviews/commentaries, and 6 book chapters. Individual works are cited hereafter, along with other relevant implementation science literature, as applicable to CFIR components.

Table 1.

Chronology of the Identified CM Transportability Literature

| Literature Citation | Pub. Type | Brief Description | CFIR Domain(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chutuape et al., 1998 | 1 | Survey (who) study of incentive preferences | 1, 4 |

| Kirby et al., 1999 | 2 | Description of dissemination issues and challenges | 1,3 |

| Petry, 2000 | 3 | Review of methods with suggested clinical guidelines/procedures | 1, 3 |

| Andrzejewski et al., 2001 | 1 | Study of clinician implementation and response to feedback | 4 |

| Petry, 2001 | 3 | Commentary on limited external validity of an efficacy study | 1 |

| Petry and Simcic, 2002 | 3 | Summary of dissemination issues and challenges | 1, 4 |

| Amass and Kamien, 2004 | 1 | Demonstration study of community support of implementation | 2, 3 |

| McGovern et al., 2004 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician attitudes about adoption | 4 |

| Kellogg et al., 2005 | 1 | Qualitative study of reactions to large-scale adoption process | 4, 3 |

| Petry et al., 2005 | 1 | CTN protocol description and primary results | 1, 5 |

| Roll et al., 2005 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician ideas about incentives | 1, 4 |

| Kirby et al., 2006 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician attitudes about adoption | 4 |

| Peirce et al., 2006 | 1 | CTN protocol description and primary results | 1, 5 |

| Stitzer and Petry, 2006 | 3 | Review of methods and effectiveness | 1 |

| Alessi et al., 2007 | 1 | Evaluation of implementation project at a set of community clinics | 1, 5 |

| Ducharme et al., 2007 | 1 | Study of organizational predictors of adoption among CTN clinics | 3, 4 |

| McCarty et al., 2007 | 1 | Description of CTN workforce and attitudes about adoption | 4 |

| Olmstead et al., 2007a | 1 | Comparative cost-effectiveness study of treatment implementation | 1 |

| Olmstead et al., 2007b | 1 | Cost-effectiveness study for implementation during CTN protocol | 1 |

| Ritter and Cameron, 2007 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician attitudes about adoption | 4 |

| Sindelar et al., 2007a | 1 | Cost-effectiveness study for implementation during CTN protocol | 1 |

| Sindelar et al., 2007b | 1 | Cost-effectiveness study for implementation during CTN protocol | 1 |

| Wong and Silverman, 2007 | 3 | Review of methods and impact of therapeutic workplace | 1, 2 |

| Amass and Kamien, 2008 | 2 | Description of methods to reduce implementation costs | 1, 3 |

| Chapman et al., 2008 | 1 | Development and psychometric evaluation of a fidelity instrument | 1 |

| Donlin et al., 2008 | 2 | Description of design and impact of therapeutic workplace | 1, 2 |

| Haug et al., 2008 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician knowledge and adoption attitudes | 4 |

| Henggeler et al., 2008a | 1 | Evaluation of large-scale clinician training effort | 4, 3 |

| Herbeck et al., 2008 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician knowledge and adoption attitudes | 4 |

| Ledgerwood et al., 2008 | 1 | Evaluation of implementation project at a set of community clinics | 1, 5 |

| Ledgerwood, 2008 | 3 | Description of implementation issues and barriers | 1, 3 |

| Marlowe and Wong, 2008 | 2 | Description of implementation issues in drug court settings | 1, 2 |

| Petry and Alessi, 2008 | 2 | Description of methods and impact of cost-effective applications | 1 |

| Squires et al., 2008 | 1 | Evaluation of large-scale training and dissemination effort | 5, 3 |

| Stitzer and Kellogg, 2008 | 2 | Description of issues in broad systemic implementation | 5, 3 |

| Lott and Jencius, 2009 | 1 | Implementation description at a community treatment organization | 5, 1 |

| Olmstead and Petry, 2009 | 1 | Cost-effectiveness comparative study for two clinical applications | 1 |

| Roll et al., 2009 | 3 | Review of adoption barriers | 1, 4 |

| Vahabzadeh et al., 2009 | 1 | Description of design and evaluation of automated implementation | 1 |

| Benishek et al., 2010 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician attitudes about adoption | 4, |

| Bride et al., 2010 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician attitudes about adoption | 4, 3 |

| Ducharme et al., 2010 | 1 | Survey-based study of clinician attitudes about adoption | 4, 3 |

| Petry et al., 2010 | 1 | Development and psychometric evaluation of a fidelity instrument | 1 |

| Petry, 2010 | 3 | Commentary on controversial issues and barriers to dissemination | 1 |

| Roman et al., 2010 | 1 | Study of long-term efforts to sustain implementation in clinics | 5,3 |

| Stitzer et al., 2010 | 3 | Review of CTN protocols and efforts to sustain implementation | 5, 3 |

| Walker et al., 2010 | 1 | Process description of attempted implementation by two clinics | 5, 3 |

| Bride et al., 2011 | 1 | Survey-based study of organizational factors influencing adoption | 3 |

| Dallery and Raiff, 2011 | 3 | Commentary on information technology in implementation | 1 |

Notes: Pub. Type enumerated as: 1=empirical study, 2=book chapter, 3=review or commentary; CFIR Domains enumerated as: 1=intervention characteristics, 2=outer setting characteristics, 3=inner setting characteristics, 4=clinician characteristics, 5=implementation processes

3. Results

3.1. Intervention characteristics

Characteristics of the intervention encompass its source of origin, complexity, perceived efficacy, relative advantage, adaptability, trialability, cost, and packaging. As noted in Table 1, these are a focus in 29 of the 49 (59%) sources of identified literature.

3.1.1 Source of Origin

Stitzer (2010) links CM conceptually to Skinner (1938), and empirical origins are noted as analog studies of operant conditioning applied to substance use initiation, maintenance, and discontinuance (Higgins et al., 2008). Implementation scientists suggest such nonclinical origins may lessen perceived legitimacy in the treatment community (Damschroder et al., 2009), though this prospect appears unrecognized in the identified literature. Notably, alternative approaches (e.g., motivational interviewing, relapse prevention) developed inductively by clinical researchers do garner more clinician interest (Benishek et al., 2010; Herbeck et al., 2008; McCarty et al., 2007; McGovern et al., 2004).

3.1.2 Complexity

Procedural complexity impedes transportability if implementation disrupts central work processes (Grol et al., 2007). This is a concern for methods reliant on complicated arithmetic formulas, as noted by Petry (2001) of escalating voucher schedules or of the variable-ratio, variable-magnitude nature of fishbowl methods. Related implementation tasks are foreign or philosophically-incongruent for many clinicians (Chutuape et al., 1998; Kirby et al., 2006). Published methodological descriptions (Ledgerwood, 2008; Petry and Alessi, 2008) may be useful clinician references for complicated methods. The identified literature suggest that many clinicians who receive CM training proceed to use it and do so effectively (Henggeler et al., 2008a; Lott and Jencius, 2009), though a more recent report (Petry et al., in press) highlights the need for ongoing supervision to prevent declines in clinician adherence and competence. Stitzer (2010) notes that NIDA blending products may increase procedural automation, though their utility remains notably unevaluated (Martino et al., 2010). Still, such efforts may mitigate some procedural complexities of CM implementation and foster better future transportability.

3.1.3 Perceived Efficacy

A common finding in identified literature is perceived efficacy by only a minority of clinicians (Benishek et al., 2010; Kirby et al., 2006; Ritter and Cameron, 2007). Similarly, just 27% support routine implementation (Benishek et al., 2010). These impressions clearly contrast with the robust effects of meta-analyses (Dutra et al., 2008; Griffith et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006; Prendergast et al., 2008). As clinicians are the dissemination consumers, correcting misperceptions of the efficacy evidence is a salient training target. To that end, brief and simple educational interventions show promise (Benishek et al., 2010; Petry et al., in press).

3.1.4 Relative Advantage

Another reliable finding is greater clinician support for alternative therapies (Bride et al., 2010; Herbeck et al., 2008; McCarty et al., 2007; McGovern et al., 2004). This is a concern, given that these alternatives may be included in treatment-as-usual practices. And Henggeler and colleagues (Henggeler et al., 2008a) do note competing clinical priorities as the most common attribute for lack of adoption among CM-trained clinicians. Nevertheless, the identified literature includes demonstration projects of CM integrated into treatment-as-usual at addiction clinics (Alessi et al., 2007; Ledgerwood et al., 2008), and descriptions for doing so in related contexts like drug courts (Marlowe and Wong, 2008), or employment settings (Donlin et al., 2008; Wong and Silverman, 2007). Clearly, improving clinician understanding of how to integrate CM with existing therapeutic approaches and practices is salient for its transportability.

3.1.5 Adaptability

The identified literature includes a large-scale example of CM adapted to the structural and economic constraints of a large health organization (Kellogg et al., 2005). Also included are broad examples of adaptation in conduct of multi-site CTN trials (Peirce et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2005), and specific modifications for implementation in group therapy (Alessi et al., 2007; Ledgerwood et al., 2008). Adaptability appears an attribute for CM transportability.

3.1.6 Trialability

Several identified sources describe pilot CM experimentation in treatment settings, and include resulting precautions and suggested practices (Henggeler et al., 2008a; Kellogg et al., 2005; Squires et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2010). A common theme is that one-size-fits-all implementation strategies are inappropriate. For example, Walker and colleagues (2010) recommend settings first implement with a circumscribed client group or behavioral outcome. Involved processes and resulting outcomes may then be closely monitored to inform decisions about sustaining, expanding, or otherwise amending procedures.

3.1.7 Cost

Financial issues are frequently noted in identified literature. Concern over basic costs of implementation—incentive purchasing/storage, toxicology screens, and staff time—are salient (Kirby et al., 1999; Kirby et al., 2006; Roll et al., 2009) and a common reason clinics forego adoption (Roman et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2010). Cost-effectiveness studies compare CM vs. treatment-as-usual (Olmstead et al., 2007b), other approaches (Olmstead et al., 2007a), or even contrast CM systems (Sindelar et al., 2007a). Some specify incremental implementation costs per outcome (Olmstead and Petry, 2009; Sindelar et al., 2007b). A common caveat that limits generalizability of these innovative analyses is that evaluation intervals overlap with conduct of clinical trials. With regard to sustaining implementation, sources describe low-cost methods (Alessi et al., 2007) or explore staff ideas for such approaches (Roll et al., 2005). Others suggest use of inexpensive items as incentives and intermittent reinforcement schedules (Petry and Alessi, 2008; Roll et al., 2009), or demonstrate durability via community donations (Amass and Kamien, 2004, 2008). Further implementation costs are those for staff training, with durable therapy implementation widely-recognized to require supervision and fidelity-monitoring after initial workshop training (Baer et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2006). Among clinicians attending a workshop and monthly phone consultations, Henggeler and colleagues (2008a) report 58% adopt with clinician-report of good fidelity. Petry and colleagues (in press) report independently-rated fidelity among 15 community-based clinicians receiving CM training and supervision, but also that competence declined when active supervision was discontinued. The resources needed to induce greater adoption rates, or provide training and supervision to attain durably competent implementation outside of a formal clinical trial remain largely unknown.

3.1.8 Packaging

The identified literature contains ideas for how to present CM to the treatment community. Roll and colleagues (2009) suggest publication in clinician-accessible outlets, with use of less technical language for concepts and procedures. Indeed, brief CM primers improve clinician knowledge and adoption readiness (Benishek et al., 2010). Others cite success in prior large-scale dissemination projects (Stitzer and Kellogg, 2008), which may sway reluctant attitudes by providing vicarious exposure to positive outcomes (Ducharme et al., 2010; Kellogg et al., 2005). Finally, the collaborative conduct of future dissemination research may further demonstrate real-world impacts and elucidate treatment community concerns (Roll et al., 2009).

3.2. Outer setting characteristics

The outer setting reflects the broader socio-economic context wherein clinics exist (Damschroder et al., 2009). Characteristics encompass client needs and resources, external networking, inter-organizational competition, and governing policies. As noted in Table 1, these are a focus in just 4 of the 49 (8%) sources in the identified literature.

3.2.1 Client needs/resources

Efficacy studies suggest no differential impact by client ethnicity (Barry et al., 2009), income (Rash et al., 2009), and psychiatric severity (Weinstock et al., 2007). Still, diverse needs and resources of treatment-seekers impact incentive choice and distribution. Preferences vary among clients and clinicians, prompting suggestions of an initial menu from which clients choose (Chutuape et al., 1998; Roll et al., 2005). While clearly a consumer-friendly idea, the identified literature contains no data-based evaluation of such an open-menu approach.

3.2.2. External networking

Implementation scientists note service organizations that promote external networking implement treatment innovations more quickly and effectively (Greenhalgh et al., 2004). With respect to the identified literature, adoption is more likely in organizations open to research collaboration (Bride et al., 2011). Multiple examples evidence adoption by linked clinics within larger health systems (Henggeler et al., 2008a; Kellogg et al., 2005), and greater effectiveness when they attempt implementation (Walker et al., 2010). Clinics’ external networking appears a salient moderating influence on CM transportability.

3.2.3. Inter-organizational competition

Implementation scientists note that peer pressure occurs among organizations (Damschroder et al., 2009). To the extent that addiction treatment reflects a marketplace, how therapeutic approaches are regarded by prospective consumers/payers merits consideration (McLellan et al., 2003). The identified literature includes two studies documenting client incentive preferences (Chutuape et al., 1998; Roll et al., 2005), though neither directly addresses the link of such preferences to broader treatment satisfaction or other consumer-oriented indices. Similarly, no identified literature examines 3rd-party payer attitudes about CM. These appear to be fruitful areas for future transportability research.

3.2.4 External governing policies

Implementation scientists note that governing policies are communicated via external mandates, clinical guidelines, pay-for-performance incentives, and public reporting (Mendel et al., 2008). The identified literature suggests more favorable attitudes exist at clinics supported by public funds or designated as non-profit corporations (Bride et al., 2011; Ducharme et al., 2007). Other sources document facilitative policies by domestic (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2011) and international bodies (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2007) that appropriate funds for staff training and pilot implementation. Some clinics may need a stronger rationale for adoption, like system-directed financial incentives for documented implementation (McLellan, 2006). And some governing bodies may require clearer data on the socioeconomic advantages of CM implementation to overcome persistent ideological barriers (Petry, 2010). It seems that governing policies, and outer setting constructs generally, are not well-recognized or understood as influences of CM transportability.

3.3 Inner setting characteristics

The inner setting reflects the internal structure and culture of clinics (Damschroder et al., 2009), with characteristics encompassing structural attributes, communication networks, organizational culture, and implementation climate. Such constructs are suggested to mediate links between the outer setting and implementation (IOM, 2001). As Table 1 indicates, inner setting characteristics are a focus in 16 of the 49 sources (32%) in identified literature.

3.3.1 Structural Attributes

Implementation scientists note size and social architecture as clinics’ primary structural attributes (Damschroder et al., 2009). Size, reflected by number of staff, does not predict adoption in identified literature (Bride et al., 2011; Ducharme et al., 2007). This is surprising, given that lack of staff time, resources, and administrative support are commonly-noted barriers (Benishek et al., 2010). Social architecture, or how staff is organized to provide services, is often clustered around particular services or clientele. In identified literature, the presence of methadone services predicts adoption whereas presence of detox services is an inverse predictor (Bride et al., 2011; Ducharme et al., 2007). With respect to client subgroups, greater adoption occurs in publicly-funded programs serving adolescents or drug-court referrals (Bride et al., 2011). Thus, several structural attributes appear to moderate transportability.

3.3.2 Communication networks

Though implementation scientists partially attribute effective implementation to quality of communication among staff (Simpson and Dansereau, 2007), this is not discussed in the identified literature. Other sources note organizational support for and facility with e-communication as a predictor of favorable adoption attitudes (Fuller et al., 2007; Hartzler et al., in press). This, taken together with emerging computer-based products for automating some communicative tasks (Dallery and Raiff, 2011; Vahabzadeh et al., 2009) suggests comfort with technology may facilitate aspects of CM transportability.

3.3.3 Organizational Culture

Implementation scientists define organizational culture as norms and values guiding the provision of service offerings (Gershon et al., 2004). Most theory-based constructs of organizational culture are not found to be predictors of clinician adoption in the identified literature (Henggeler et al., 2008a). A more practical construct—staff turnover—merits some consideration, as it affects implementation by prompting need to re-train replacement staff. Of a large training and implementation project, Squires and colleagues (2008) note turnover as particularly challenging when departed staff have been opinion leaders or champions. Impacts of staff turnover on CM implementation quality and durability do warrant scientific attention.

3.3.4 Implementation Climate

Implementation climate is an absorptive capacity for change and shared receptivity to innovations (Damschroder et al., 2009; Greenhalgh et al., 2004). It is often represented in measures of adoption readiness, which predicts training participation (Henggeler et al., 2008a). Staff disinterest and perceived philosophical incongruence are common detriments to adoption readiness (Benishek et al., 2010; Roman et al., 2010), but director championing can override these (Kellogg et al., 2005). In fact, 80+% training attendance rates are seen after simple efforts like statement of director approval and provision at convenient times (Henggeler et al., 2008b). Organizational change strategies also spur greater participation in available trainings (Squires et al., 2008). The identified literature offers no training outcome data, but sources do suggest benefit in use of performance-based feedback, booster sessions, and ongoing supervision (Andrzejewski et al., 2001; Henggeler et al., 2008b). Clearly, further study of organizational conditions that promote adoption readiness and training participation is needed.

3.4 Clinician characteristics

Salient characteristics include clinicians’ professional background, beliefs, self-efficacy, and organizational perception. As noted in Table 1, these are a focus in 17 of 49 works (34%) in the identified literature.

3.4.1 Professional background

Focal indices are education, clinic role, and tenure. Findings are equivocal for education as an idiographic predictor of adoption readiness (Ducharme et al., 2010; Henggeler et al., 2008a; Herbeck et al., 2008; Kirby et al., 2006). When aggregated to clinic-level (% with graduate degree), it fails to predict implementation (Bride et al., 2011; Ducharme et al., 2007). Clinical role does reliably predict adoption attitudes, with supervisors holding more favorable views (Hartzler et al., in press; Kirby et al., 2006; McCarty et al., 2007). Staff tenure and implementation experience also predict adoption readiness (Ducharme et al., 2010; Kirby et al., 2006). Recognition of these and other predictive characteristics aids in identifying opinion leaders, who may then spur wider clinic support for implementation (Rogers, 2003).

3.4.2 CM beliefs

Identified literature suggests much variance in CM beliefs, and moderation by professional role and experience (Ducharme et al., 2010; Henggeler et al., 2008a; Herbeck et al., 2008; Kirby et al., 2006; McGovern et al., 2004). Philosophical objections to use of monetary incentives are prevalent (Ducharme et al., 2010; Petry and Simcic, 2002; Ritter and Cameron, 2007), with nearly half the treatment community endorsing this as akin to bribery (Kirby et al., 2006). The identified literature also includes suggested use of client testimonials to sway such strongly-held opinions (Kellogg et al., 2005; Roll et al., 2009; Stitzer et al., 2010). This and other efforts to modify the treatment community attitudes merit further scientific attention.

3.4.3 Self-efficacy

In theory, clinician self-efficacy for CM implementation might be expected to influence adoption decisions and implementation quality (Bandura, 1977). Yet, it is absent any discussion in identified literature. Identified sources suggest clinicians with implementation experience view CM more positively (Ducharme et al., 2010), and that 58% of CM-trained staff attempt implementation (Henggeler et al., 2008a). Such findings may well be influenced by how confident individual clinicians feel about their implementation skills. Future research in this area is warranted, particularly regarding clinician self-efficacy in specific CM tasks, and this may become recognized as a salient target for training, supervision, and other support processes.

3.4.4 Organizational perception

As earlier noted, most theory-based indices of clinician-rated organizational perception do not predict adoption readiness. Henggeler and colleagues (2008a) report that perceived openness to change predicts implementation quality. A commonly-endorsed treatment community sentiment is that new methods be adopted only if ‘they don’t conflict with treatments already in place’ (Haug et al., 2008). This perspective may explain why clinics that strongly ascribe to 12-step ideology have weak adoption attitudes for CM (Ducharme et al., 2010) and other empirically-supported behavior therapies (McGovern et al., 2004). This appears to be a poignant barrier for transportability of CM, and of treatment innovations in general.

3.5 Implementation processes

A sequence of implementation processes includes planning, engagement, execution, and evaluation stages. Table 1 notes these as a focus in 9 of 49 sources (18%) of identified literature.

3.5.1 Planning

A fundamental planning objective is to build local capacity for eventual routine use (Mendel et al., 2008). The identified literature includes description of planning efforts in multiple, successful systemic implementations (Henggeler et al., 2008a; Kellogg et al., 2005). Stitzer and Kellogg (2008) also describe planning for CTN trials and post-trial dissemination. A need for contextualization is a common theme in these sources, with planning efforts varying as a function of clinic size, resources, and capacity to mobilize around new initiatives. Walker and colleagues (2010) suggest: 1) securing necessary funding early, 2) including a pilot period where initial procedural problems are resolved, and 3) expecting initial staff reluctance. Reported planning intervals for clinic implementation are 2–6 months, with lengthier intervals minimizing implementation challenges (Walker et al., 2010). Planning intervals are much longer in systemic or multi-site implementations (Henggeler et al., 2008a; Kellogg et al., 2005; Squires et al., 2008).

3.5.2 Engaging

Staff engagement is critical, given common sources of reluctance (Kirby et al., 2006). The identified literature contains several accounts of engagement efforts. For instance, CTN investigators elicited clinic feedback to inform site-specific adaptations in the multi-site trial (Peirce et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2005). Stitzer and Kellogg (2008) also note use of on-site dissemination coordinators to engage post-trial implementation by CTN clinics. Kellogg and colleagues (2005) initially engaged a system of clinics via promotional presentations given to corporate leadership. Implementation scientists (Damschroder et al., 2009) suggest that engagement processes target: 1) opinion leaders to influence staff opinions via authority, status, or credibility, 2) implementation leaders to coordinate implementation efforts, 3) champions to market CM and mitigate staff resistance, and 4) external change agents to garner support from payers and governing bodies. To that end, the identified literature includes an example wherein advocates worked collaboratively with clinic management to designate implementation leaders and champions, and to maintain contact with external change agents (Squires et al., 2008).

3.5.3 Executing

Execution relies on maintaining fidelity to specified implementation procedures (Carroll et al., 2007). Walker and colleagues (2010) note as fidelity challenges among clinics’ implementation attempts a loss of staff control over incentives and failure to accurately reset reinforcement opportunities. The identified literature includes sources that may aid clinicians and clinics in addressing such issues. Some sources offer clinical guidelines and practical implementation ideas (Petry, 2000; Stitzer and Petry, 2006) that may be used as reference materials. Also, Stitzer and Kellogg (2008) note how on-site dissemination coordinators offered fidelity monitoring and feedback to CTN clinics during post-trial implementation attempts. And another source suggests that clinics stagger initial CM implementation between service lines or client groups to limit the impact of initial execution problems (Walker et al., 2010).

3.5.4 Evaluating

Implementation is a large undertaking, and implementation scientists suggest its evaluation be approached in specific, measureable ways (Damschroder et al., 2009). An obvious evaluation target for CM implementation projects is the rate at which it is adopted. Henggeler and colleagues (2008a) note an adoption rate of 58% among clinicians attending an initial workshop, and that this was more likely among those with more experience, longer clinic tenure, and greater initial interest. A related evaluation target is fidelity of implementation once adopted. The identified literature includes validation studies for staff-level fidelity instruments (Chapman et al., 2008; Petry et al., 2010), and Henggeler and colleagues (2008a) report use of such a measure to document longitudinal improvement in fidelity. With respect to evaluating clinical impact, demonstration projects in the identified literature understandably report outcome measures synonymous with client behaviors targeted by behavioral reinforcement (Alessi et al., 2007; Ledgerwood et al., 2008; Lott and Jencius, 2009) and do so via repeated-measures designs.

4. Discussion

This structured review examined CM transportability literature according to dimensions of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009), an established implementation science model. An exhaustive literature search identified 49 sources, consisting of 33 empirical studies, 10 commentaries/reviews and 6 book chapters. This is dwarfed by available efficacy literature, which is neither surprising nor specific to CM (Carroll and Rounsaville, 2007). But it does underscore a need that further scientific attention be given to how and how effectively CM methods transition from their innovators in academia to clinical professionals in the treatment community.

Among CFIR domains, intervention characteristics were a topical focus in a majority of the identified literature. Even so, what is understood about how such characteristics impact the community implementation of CM appears a series of moving targets. For instance, procedural complexity is a recognized challenge, particularly for tasks falling outside of traditional clinician training; however, publication of procedural details and clinical guidelines as well as design of products to automate tasks all provide hope for the future. Lack of familiarity, or misperception of, CM efficacy evidence is common. Educational tools to promote greater awareness intend to help, but they and dissemination efforts surrounding them merit formal evaluation. Adaptation is documented for various settings and modalities, yet greater understanding is needed of how CM is conceptually integrated with other behavior therapies in common use with substance users. Promising results of cost-effectiveness analyses and creative ideas to minimize overhead costs may abate some treatment community concerns. Still, more detail is needed for overlooked costs like those for community-based training and supervision activities to ensure effective, durable implementation. Continued conduct of collaborative demonstration projects by academicians and treatment clinics will further inform packaging of training/promotional materials, while providing insight into sources of reactance in the treatment community.

The influence of organizational constructs, particularly outer setting characteristics, is not well-recognized or accounted for in most identified literature. Clinic networking and supportive economic policies seem to facilitate adoption, and their influence on implementation quality and durability merits study. The feasibility and therapeutic impact of creative ideas to incorporate idiographic client preferences, like use of incentive menus, also merit evaluation. Prospective dissemination research should include focus on attitudes toward CM among clients, whose preferences provide important data from a consumer-marketing perspective. Similarly, attitudes toward CM among 3rd-party payers are likely to be informative. Inner setting characteristics of clinics were more frequently discussed in the identified literature, but also merit greater focus in research and dissemination efforts. Advocacy by leadership, use of e-communication (and comfort with technology in general), and staff continuity appear salient predictors of adoption readiness. The presence of these and other structural attributes of clinics (e.g., services provided, populations served) may moderate adoption rates and implementation quality. Variance in such topographical clinic features deserves greater recognition from CM advocates/trainers, and underscores the need for tailored—rather than one-size-fits-all—dissemination strategies.

Characteristics of front-line clinicians who would serve as agents of CM implementation are another salient area where transportability literature is in its infancy. Clinic tenure, prior implementation experience, and a supervisory clinic role reliably predict adoption readiness, but the role of other clinician attributes is unclear or unknown. The noted predictors also appear to moderate CM beliefs among clinicians, which include fairly prevalent antagonism toward use of monetary incentives and their likening to a form of bribery. The impact of client testimonials, and other promotional efforts, in altering such poignant treatment community beliefs should be formally evaluated. Greater effort may be needed of CM advocates to work with clinics to identify high-magnitude incentives that are philosophically-congruent for staff. In terms of predicting implementation quality, little is known of associated clinician attributes. Perceived organizational openness to change is one reported predictor, but others merit study. An example is clinician self-efficacy for implementation, which to date is unstudied as a predictor of adoption readiness or implementation quality. Allegiance to prevailing addiction treatment ideologies also bears consideration. All are areas ripe for future research, as is identification of attributes that suit individual staff for specific roles in processes of systemic implementation.

The identified literature provides descriptive examples of staged processes in which CM advocates collaborated with clinics to plan, engage in, execute, and evaluate implementation. Many demonstration projects highlight points of success; however, descriptions of problematic implementation are no less informative. Taken together, these experiential accounts serve as blueprints (or cautionary tales) to those considering future implementation. Broadly, benefit is suggested in: 1) careful planning for funding and logistics, 2) engagement of interested staff in specific roles (e.g., implementation leaders, champions, external agents), 3) staggered onset and practical adaptation during execution, and 4) fidelity-monitoring and cost-effectiveness analyses as means of evaluation. Published description of these suggested processes and their outcomes in future clinic implementations would be valued additions to transportability literature. Further, description of processes whereby clinicians are designated for implementation roles, and their attainment of task proficiency, would also be useful additions to extant literature.

Some caveats bear mentioning. This structured literature review is impacted by limitations inherent in its original sources. Empirical studies of clinician or organizational characteristics often relied on self-report methodology, potentially impacted by demand characteristics or other forms of impression management. Demonstration projects detailing training and implementation processes were often quasi-experimental, failing to control for temporal changes in knowledge, attitudes, adoption readiness, or implementation quality that might have otherwise occurred. And many book chapters or commentaries contain practical and well-intended suggestions that are as yet empirically untested. With respect to our search strategy, parameters for history and language may have excluded relevant studies conducted before 1980 or in non-English speaking locales. Further. a clear majority of identified literature (and all cited systemic implementations) occurred in North America. Finally, a caveat of any literature review is publication bias, for which impact may be inversely proportional to the size of the literature base reviewed. It is difficult to know how many ‘file-drawer’ studies of CM implementation may exist, but any and all such studies would augment understanding of CM implementation constructs and processes.

5. Conclusions

Caveats notwithstanding, this review examined CM transportability literature according to dimensions of an established implementation science model. Search results identified literature that informs the guarded conclusions offered herein. There remains a great deal to study and learn about the predictors and processes of community-based CM adoption and implementation in addiction treatment settings. The identified literature does inform the set of suggestions provided for specific areas meriting future empirical attention, but those suggestions are by no means exhaustive. Diffusion of any new practice brings its advocates face-to-face with unique challenges, and the value of implementation science models is their offer of a framework to anticipate, examine, understand, and overcome such challenges. This review has summarized important prior efforts undertaken to foster CM transportability. But this work is in its infancy, and there is much more to do to bridge science-to-practice gaps and prompt greater use of this empirically-supported behavior therapy by the treatment community.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by a career development award from NIDA #DA025678-01-A2 (Integrating Behavioral Interventions in Substance Abuse Treatment, Hartzler PI).

Footnotes

Contributor

Dr. Hartzler conceptualized the review, conducted the literature search, and drafted an initial version of the manuscript. Drs. Lash and Roll provided conceptual feedback and suggested revisions that were incorporated into the eventual version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alessi SM, Hanson T, Wieners M, Petry NM. Low-cost contingency management in community clinics: delivering incentives partially in group therapy. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2007;15:293–300. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amass L, Kamien JB. A tale of two cities: financing two voucher programs for substance abusers through community donations. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2004;12:147–155. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amass L, Kamien JB. Funding contingency management in community clinics: use of community donations and clinic rebates. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 280–297. [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski ME, Kirby KC, Morral AR, Iguchi MY. Technology transfer through performance management: the effects of graphical feedback and positive reinforcement on drug treatment counselors’ behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATTC. The Change Book: A Blueprint for Technology Transfer. Addiction Technology Transfer Center; Kansas City, MO: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Ball SA, Campbell BK, Miele GM, Schoener EP, Tracy K. Training and fidelity monitoring of behavioral interventions in multi-site addictions research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice Hall; New Jersey: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barry D, Sullivan B, Petry NM. Comparable efficacy of contingency management for cocaine-dependence among African American, Hispanic, and White methadone maintenance clients. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:168–174. doi: 10.1037/a0014575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benishek LA, Kirby KC, Dugosh KL, Pavodano A. Beliefs about the empirical support of drug abuse treatment interventions: A survey of outpatient treatment providers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bride BE, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Diffusion of contingency management and attitudes regarding its effectiveness and acceptability. Subst Abuse. 2010;31:127–135. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2010.495310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bride BE, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Organizational factors associated with the use of contingency management in publicly funded substance abuse treatment centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. A vision of the next generation of behavioral therapies research in the addictions. Addiction. 2007;102:850–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JE, Sheidow AJ, Henggeler SW, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB. Developing a measure of therapist adherence to contingency management: an application of the Many-Facet Rasch model. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2008;17:47–68. doi: 10.1080/15470650802071655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MA, Silverman K, Stitzer ML. Survey assessment of methadone treatment services as reinforcers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24:1–16. doi: 10.3109/00952999809001695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Contingency management in the 21st century: technological innovations to promote smoking cessation. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:10–22. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn H. A guiding framework and approache for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:194–206. doi: 10.1037/a0022284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlin WD, Knealing TW, Silverman K. Employment-based reinforcement in the treatment of drug addiction. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency management in substance abuse treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 314–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Counselor attitudes toward the use of motivational incentives in addiction treatment. Am J Addict. 2010;19:496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK, Roman PM, Johnson J. Innovation adoption in substance abuse treatment: exposure, trialability, and the Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen D, Naoom S, Blase KA, Friedman RMFW. Louis de la Pate Florida Mental Health Institute, T.N.I.R.N. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida; Tampa, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller BE, Rieckmann T, Nunes EV, Miller M, Arfken C, Edmundson E, McCarty D. Organizational Readiness for Change and opinions toward treatment innovations. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon R, Stone PW, Bakken S, Larson E. Measurement of organizational culture and climate in healthcare. J Nurs Admin. 2004;34:33–40. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, Simpson DD. Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol RP, Bosch MC, Hulscher ME, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85:93–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GR, Leshner AI, Tai B. Putting drug abuse research to use in real-life settings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:69–70. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Donovan DM, Tillotson C, Mongoue-Tchokote S, Doyle S, McCarty D. A multi-level approach to predicting community addiction treatment attitudes about contingency management. J Subst Abuse Treat. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug NA, Shopshire M, Tajima B, Gruber VA, Guydish J. Adoption of evidence-based practice s among subtance abuse treatment providers. J Drug Educ. 2008;38:181–192. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.2.f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Chapman JE, Rowland MD, Holliday-Boykins CA, Randall J, Shackelford J, Schoenwald SK. Statewide adoption and initial implementation of contingency management for substance-abusing adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008a;76:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ, Cunningham PB, Donohoe BC, Ford JD. Promoting the implementation of an evidence-based intervention for adolescent marijuana abuse in community settings: testing the use of intensive quality assurance. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008b;37:682–689. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbeck DM, Hser Y, Teruya C. Empirically supported substance abuse treatment approaches: a survey of treatment providers’ perspectives and practices. Addict Behav. 2008;33:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes J, Foerg FE, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Roerg F, Badger GJ. Achieving cocaine abstinence with a behavioral approach. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:763–769. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. Guilford; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. Washington, D.C: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st century. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg SH, Burns M, Coleman P, Stitzer ML, Wale JB, Kreek MJ. Something of value: the introduction of contingency management interventions into the New York City Health and Hospital Addiction Treatment Service. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KC, Amass L, McLellan AT. Disseminating contingency management research to drug abuse treatment practitioners. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, editors. Motivating Behavior Change Among IIlicit Drug Abusers: Research on Contingency Management Interventions. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C: 1999. pp. 327–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KC, Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kerwin ME. Substance abuse treatment providers’ beliefs and objections regarding contingency management: implications for dissemination. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash SJ, Stephens RS, Burden JL, Grambow SC, DeMarce JM, Jones ME, Lozano BE, Jeffreys AS, Fearer SA, Horner RD. Contracting, prompting, and reinforcing substance use disorder continuing care: a randomized clinical trial. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:387–397. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM. Contingency managementfor smoking cessation: where do we go from here? Current Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:340–349. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801030340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Godley MD, Petry NM. Contingency management for attendance to group substance abuse treatment administered by clinicians in community clinics. J Appl Behav Anal. 2008;41:517–526. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott DC, Jencius S. Effectiveness of very low-cost contingency management in a community adolescent treatment program. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe DB, Wong CJ. Contingency management in adult criminal drug courts. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 334–354. [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Brigham GS, Higgins C, Gallon S, Freese TE, Albright LM, Hulsey EG, Krom L, Storti SA, Perl H, Nugent CD, Pintello D, Condon TP. Partnerships and pathways of dissemination: the National Institute on Drug Abuse -Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Blending Initiative in the Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:S31–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty DJ, Fuler BE, Arfken C, Miller M, Nunes EV, Edmundson E, Copersino M, Floyd A, Forman R, Laws R, Magruder KM, Oyama M, Prather K, Sindelar J, Wendt WW. Direct care workers in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network: Characteristics, opinions, and beliefs. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:181–190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Fox TS, Xie H, Drake RE. A survey of clinical practices and readiness to adopt evidence-based practicies: dissemination research in an addiction treatment system. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT. What we need is a system: creating a responsive and effective substance abuse treatment system. In: Miller WR, Carroll KM, editors. Rethinking Substance Abuse: What the Science Shows, and What We Should Do About It. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD. Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public’s demand for quality care? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Interventions in organizational and community context: a framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research. Adm Policy Ment Hlth. 2008;35:21–37. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milby JB, Garrett C, English C, Fritschi O, Clarke C. Take-home methadone: contingency effects on drug-seeking and productivity of narcotic addicts. Addict Behav. 1978;3:215–220. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: a review with suggestions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E. NICE Clinical Guidelines. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; London, UK: 2007. Drug misuse: Psychosocial Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Petry NM. The cost-effectiveness of prize-based and voucher-based contingency management in a population of cocaine- or opioid-dependent outpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Sindelar J, Easton C, Carroll KM. The cost-effectiveness of four treatments for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 2007a;102:1443–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Sindelar J, Petry NM. Cost-effectiveness of prize-based incentives for stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007b;87:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellogg S, Satterfield F, Schwartz M, Krasnansky J, Pencer E, Silva-Vazquez L, Kirby KC, Royer-Malvestuto C, Roll JM, Cohen A, Copersino ML, Kolodner K, Li R. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Challenges in the transfer of contingency management techniques: comment on Silverman et al (2001) Exp Clin Psychopharm. 2001;9:24–26. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Contingency management treatments: controversies and challenges. Addiction. 2010;105:1507–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Ledgerwood DM. Contingency management delivered by community therapists in outpatient settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. Guilford Press; New York: pp. 261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Ledgerwood DM, Sierra S. Psychometric properties of the Contingency Management Competence Scale. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Peirce J, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Roll JM, Cohen A, Obert J, Killeen T, Saladin ME, Cowell M, Kirby KC, Sterling R, Royer-Malvestuto C, Hamilton J, Booth RE, Macdonald M, Liebert M, Rader L, Burns R, DiMaria J, Copersino M, Stabile PQ, Kolodner K, Li R. Effect of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs: a national drug abuse treatment clinical trials network study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005:62. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Simcic F. Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: clinical and research perspectives. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Hall EA, Roll JM, Warda U. Use of vouchers to reinforce abstinence and positive behaviors among clients in a drug court treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney JW, Greenwell L, Roll JM. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash CJ, Olmstead TA, Petry NM. Income does not affect response to contingency management treatments among community substance abuse treatment-seekers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A, Cameron J. Australian clinician attitudes towards contingency management: comparing down under with America. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Chudzynski JE, Richardson G. Potential sources of reinforcement and punishment in a drug-free treatment clinic: client and staff perceptions. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2005;1:21–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Madden GJ, Rawson R, Petry NM. Facilitating the adoption of contingency management for the treatment of substance use disorders. Behav Anal Prac. 2009;2:4–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03391732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman PM, Abraham AJ, Rothrauff TC, Knudsen HK. A longitudinal study of organizational formation, innovation adoption, and dissemination activities within the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:S44–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: getting started and moving on from stage I. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Pugh J. Strategies for promoting organizational and practice change by advancing implementation research. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S58–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Wong CJ, Needham M, Diemer KN, Knealing T, Crone-Todd D, Fingerhood M, Nuzzo P, Kolodner K. A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. J Appl Behav Anal. 2007;40:387–410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Dansereau DF. Assessing organizational functioning as a step toward innovation. NIDA Sci Prac Pers. 2007;3:20–28. doi: 10.1151/spp073220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar J, Ebel B, Petry NM. What do we get for our money? Cost-effectiveness of adding contingency management. Addiction. 2007a;102:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar J, Olmstead TA, Peirce J. Cost-effectiveness of prize-based contingency management in methadone maintenance treatment programs. Addiction. 2007b;102:1463–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis. Appleton-Century Company, Inc; New York: 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Squires DD, Gumbley SJ, Storti SA. Training substance abuse treatment organizations to adopt evidence-based practices: the Addiction Transfer Center of New England Science-to-Service Laboratory. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Lawrence C, Cohen J, D’Lugoff B, Hawthorne J. Medication take-home as a reinforcer in a methadone maintenance program. Addict Behav. 1977;2:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(77)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Reducing drug use among methadone maintenance clients: contingent reinforcement for morphine-free urines. Addict Behav. 1980;5:333–340. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(80)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Kellogg S. Large-scale dissemination efforts in drug abuse treatment clinics. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Petry NM. Contingency management for treatment of substance abuse. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:411–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Petry NM, Peirce J. Motivational incentives research in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:S61–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The COMBINE Study Research Group. Testing combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions in alcohol dependence: rationale and methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1107–1122. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treweek S, Zwarenstein M. Making trials matter: pragmatic and explanatory trials and the problem of applicability. Trials. 2009;10:37. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Programs for Veterans with Substance Use Disorders (SUD): VHA Handbook 1160.xx. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington, D.C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UKATT Research Team. Effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: Findings of the randomized UK alcohol treatment trial (UKATT) BMJ. 2005:331. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Mezghanni M, Epstein DH, Preston KL. Automation in an addiction treatment research clinic: computerised contingency management, ecological momentary assessment and a protocol workflow system. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R, Rosvall T, Field CA, Allen S, McDonald D, Salim Z, Ridley N, Adinoff B. Disseminating contingency management to increase attendance in two community substance abuse treatment centers: lessons learned. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock J, Alessi SM, Petry NM. Regardless of psychiatric severity the addition of contingency management to standard treatment improves retention and drug use outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CJ, Silverman K. Establishing and maintaining job skills and professional behaviors in chronically unemployed drug abusers. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:1127–1140. doi: 10.1080/10826080701407952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]