Abstract

Cigarette smoking is ubiquitous among illicit drug users. Some have speculated that this may be partially due to similarities in the route of administration. However, research examining the relationship between cigarette smoking and routes of administration of illicit drugs is limited. To address this gap, we investigated sociodemographic and drug use factors associated with cigarette smoking among cocaine and heroin users in the Baltimore, Maryland community (N=576). Regular and heavy cigarette smokers were more likely to be White, have a history of a prior marriage, and have a lower education level. Regular smoking of marijuana and crack was associated with cigarette smoking, but not heavy cigarette smoking. Injection use was more common among heavy cigarette smokers. In particular, regular cigarette smokers were more likely to have a lifetime history of regularly injecting heroin. Optimal prevention and treatment outcomes can only occur through a comprehensive understanding of the interrelations between different substances of abuse.

Keywords: polydrug, tobacco, epidemiology, routes of administration, cocaine, heroin

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is associated with increased mortality among heroin and cocaine users (Hser, et al., 1994; Hurt, et al., 1996). Many substance abuse clinicians resist addressing tobacco use, claiming that substance users are uninterested in such treatment, and that it would hinder treatment for illicit substances (Guydish, Passalacqua, Tajima, & Manser, 2007; Weinberger & Sofuoglu, 2009). However, most opioid-dependent patients are interested in quitting smoking (Clarke, Stein, McGarry, & Gogineni, 2001; Clemmey, Brooner, Chutuape, Kidorf, & Stitzer, 1997), quitting smoking is associated with less use of other substances (Kohn, Tsoh, & Weisner, 2003; Satre, Kohn, & Weisner, 2007), and cigarette smoking is a predictor of worse illicit treatment outcomes (Frosch, et al., 2000; Frosch, et al., 2002; Harrell, Montoya, Preston, Juliano, & Gorelick, 2011). Further, smoking cessation treatment is effective for smokers dependent on illicit substances (Burling, Burling, & Latini, 2001) and inconsequential to substance abuse treatment outcome (Gariti, et al., 2002), although the ideal timing for such treatment is controversial (Joseph, Willenbring, Nugent, & Nelson, 2004; but see Baca & Yahne, 2009; Fu, et al., 2008).

Cigarette consumption may have a different relationship with opioid use than with cocaine use. Cigarette smoking predicts poorer cocaine treatment outcomes, but has an ambiguous relationship with opioid treatment outcomes (Harrell et al, 2011); likewise, the relationship between craving or use of cigarettes and cocaine may be stronger than the same relationship between cigarettes and heroin (Epstein, Marrone, Heishman, Schmittner, & Preston, 2010). Stimulus generalization may explain this disparity. In the US, crack cocaine smoking is more common than heroin smoking (SAMHSA, 2009). Cues for drug intake are associated with increased craving among substance users (Carter & Tiffany, 1999) and stimulus generalization predisposes individuals to relapse (Siegel & Ramos, 2002). Thus, lighters, smoke, and other stimuli that occur with both cigarette and crack smoking may interfere with abstinence attempts. If stimulus generalization does occur, it would provide further evidence that – particularly for those who smoke other substances, such as marijuana or crack – tobacco dependence can hinder sustained recovery and should be addressed with substance abuse treatment.

The goal of this study is to examine epidemiological evidence for stimulus generalization. One type of evidence that may support stimulus generalization would be if cigarette smoking is associated with increased smoking of other substances. Research examining the relationship between the route of administration (ROA) of cocaine/heroin and cigarette smoking is limited. Cigarette smoking is nearly ubiquitous among cocaine and heroin users (Clemmey et al., 1997; Patkar et al., 2002), so examining the extremely rare non-smokers is unlikely to provide useful information. Comparing heavy cigarette smokers with lighter smokers may be a more productive approach. Twenty or more cigarettes per day (CPD) may be a convenient and appropriate cut-off to describe heavier smokers relative to lighter smokers. Self-reports of CPD typically cluster around a pack (20) a day, a phenomenon called “digit bias” (Klesges, Debon, & Ray, 1995). These biases represent a validity problem, but self-report nonetheless performs similarly to more complicated methods, such as Ecological Momentary Assessment, in discriminating less severe from more severe smokers (Klesges, et al., 1995; Shiffman, 2009). In other words, although it is unlikely that individuals who smoke 19 CPD differ substantially from those who smoke 20 CPD, it is likely that individuals who – due to digit bias – report smoking 20+ CPD may differ substantially from those who report smoking less than 20 CPD. The present study examines associations of cigarette smoking with sociodemographic variables and various methods of administering illicit drugs in a sample of recent users in Baltimore, MD. We hypothesize that 1) the most commonly reported CPD will be 20; and 2) higher rates of smoking, particularly smoking 20+ CPD, will be associated with increased smoking of other substances, supporting stimulus generalization.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The present study used baseline data from the NEURO-HIV Epidemiologic study (Severtson, Mitchell, Hubert, & Latimer, 2010). The Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health approved and monitored this study. This sample includes 576 participants who reported using cocaine and/or heroin in the past 6 months.

2.2 Measures

HIV-Risk Behavior Interview

Smoking severity was assessed by average number of CPD in the past week. Variables related to cigarette smoking in the general population were included, such as race (Pinsky, 2006; Siahpush, Singh, Jones, & Timsina, 2010), education (Pampel, 2009), martial status (Fleming, White, & Catalano, 2010), homelessness (Lee, et al., 2005), occupational status (Shavers, Lawrence, Fagan, & Gibson, 2005), and parental drug use (Barrett & Turner, 2006). We were particularly interested in the role of income source in cigarette smoking (Farrelly, Bray, Pechacek, & Woollery, 2001; Siahpush, Wakefield, Spittal, Durkin, & Scollo, 2009). “Previously married” included any participants that were divorced, separated, or widowed. “Parental drug use” refers to drug use by a parent during the childhood of the participant. For “Substances ever used”, separate questions are asked based on ROA. Questions regarding heroin injection, for example, are asked separately from questions regarding heroin smoking. Sixty-three substance-ROA pairs are included. We conducted chi-square and logistic regression analyses for any substance use or any regular use of alcohol, marijuana, or any form of cocaine/heroin use endorsed by 5% or more of the sample. Regular substance use was defined as ever using the substance daily or nearly daily for 3 months or more.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Four smoking groups were created: 1) “non-smokers” (0 CPD); 2) “light smokers” (1–19 CPD); 3) “regular smokers” (a pack, or 20 CPD); and 4) “heavy smokers” (over 20 CPD). Comparisons between groups were conducted using chi-square (χ2) tests for urinalysis results, main income source, any lifetime use, and any regular use. Odds Ratios for regular/heavy cigarette smoking, i.e., smoking 20 or more CPD versus smoking less than 20 CPD, were determined by univariate and multivariate logistic regression. Substance-ROA pairs were examined in separate models due to multicollinearity concerns (Morton, 1977). We adjusted for the number of illicit substances ever used and sociodemographic variables to reduce the influence of potential confounders.

3. Results

3.1 Cigarette self-report clustering

The vast majority (91%) reported daily cigarette smoking. Similar to prior literature (Klesges, et al., 1995; Shiffman, 2009), the most frequently reported number of CPD was 20 (n = 204;35%). Few (6%) reported smoking between 11 and 18 CPD and no participant reported smoking 19, or 21–24 CPD, demonstrating the presence of “digit bias”, i.e., a tendency to report smoking exactly 20 CPD (Klesges, et al., 1995; Shiffman, 2009).

3.3 Drug use characteristics

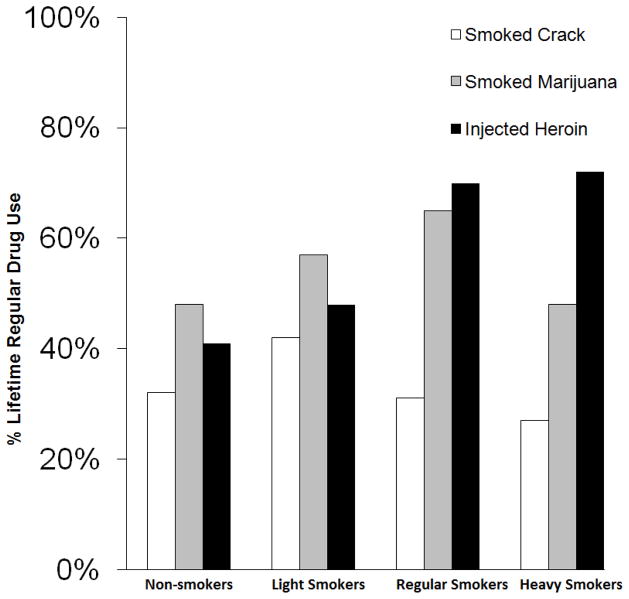

Chi-square revealed significant differences by smoking status for opioid-positive urinalysis (p<.01), main source of income (p < .01), any lifetime injection of cocaine (p<.01), heroin (p<.01), or speedball (p=.03), and any history of regularly either smoking marijuana (p=.03), smoking crack (p=.047), or injecting heroin (p<.01). Over three-quarters of heavy smokers were positive for opioids (83%), compared to slightly over half of non-smokers (51%). More heavy smokers’ main source of income was a regular job (32%) than non-smokers (19%). Non-smokers’ main income source differed from heavy smokers (p=.03), but not light smokers (p=.18). Large majorities of heavy smokers have injected cocaine (58% vs. 43%), heroin (83% vs. 50%), or speedball (60% vs. 41%), compared to no more than half of non-smokers. Most light smokers regularly smoked marijuana (57%), compared to less than half of both heavy smokers (48%) and non-smokers (48%). Similarly, many light smokers regularly smoked crack (42%), compared to heavy smokers (27%) and non-smokers (32%). The pattern for heroin injection was more linear. Over two-thirds of heavy smokers regularly injected heroin (72%), compared to less than half of non-smokers (41%). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentages of illicit drug users who reported smoking crack, smoking marijuana, or injecting heroin regularly during their lifetime as a function of cigarette smoking status. Regular drug use was defined as using every day or nearly every day for three months or more.

3.4 Odds of Regular/Heavy Cigarette Smoking

See Table 1 for odds of regular/heavy cigarette smoking based on sociodemographic and drug use variables. Examination of lifetime regular drug use revealed that in the unadjusted model, lifetime history of regular marijuana smoking, heroin injection, and “speedball” injection were associated with increased risk of regular/heavy cigarette smoking. Only injection of heroin remained significant when controlling for sociodemographic and comorbidity variables.

Table 1.

Correlates of regular/heavy cigarette smoking (a pack a day or greater) among a sample of 576 recent1 cocaine and/or heroin users in Baltimore, Maryland.

| Total | OR2 | 95% C.I.3 | AOR4 | 95% C.I.3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics and Polydrug use | |||||

| Age | 33.0±7.4 | 0.95 | 0.93, 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.95, 1.01 |

| Female Gender | 235(41%) | 0.83 | 0.60, 1.16 | 1.11 | 0.75, 1.63 |

| White Race | 276 (48%) | 4.41 | 3.11, 6.26 | 3.02 | 1.93, 4.73 |

| High School Diploma or GED | 248(43%) | 0.64 | 0.46, 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.44, 0.95 |

| Previously Married | 129 (22%) | 1.60 | 1.08, 2.38 | 2.00 | 1.26, 3.18 |

| Recent1 Homelessness | 117 (20%) | 1.28 | 0.85, 1.93 | 1.09 | 0.69, 1.73 |

| Recent1 Income from Regular Job | 143 (25%) | 1.40 | 1.00, 1.95 | 1.39 | 0.94, 2.05 |

| Parental Drug Use During Childhood | 253 (47%) | 1.04 | 0.75, 1.44 | 0.80 | 0.55, 1.17 |

| Number of Illicit Substances Ever Used | 10.7±6.3 | 1.09 | 1.05, 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.01, 1.08 |

| Lifetime Regular5 Drug Use | |||||

| Drank Alcohol | 336(59%) | 1.16 | 0.83, 1.62 | 1.08 | 0.74, 1.57 |

| Smoked Marijuana | 331(58%) | 1.49 | 1.07, 2.08 | 1.13 | 0.76, 1.69 |

| Snorted Cocaine | 109(19%) | 1.13 | 0.75, 1.72 | 1.21 | 0.75, 1.94 |

| Smoked Crack | 204(35%) | 0.84 | 0.60, 1.18 | 1.12 | 0.75, 1.68 |

| Injected Cocaine | 113(20%) | 1.29 | 0.85, 1.95 | 0.94 | 0.58, 1.53 |

| Snorted Heroin | 323(56%) | 1.00 | 0.72, 1.40 | 1.27 | 0.87, 1.85 |

| Injected Heroin | 332(58%) | 2.59 | 1.84, 3.64 | 1.58 | 1.05, 2.39 |

| Snorted Speedball | 47(8%) | 1.00 | 0.55, 1.82 | 1.34 | 0.69, 2.63 |

| Injected Speedball | 123(21%) | 1.51 | 1.01, 2.25 | 1.52 | 0.96, 2.40 |

Statistically significant findings appear in bold.

‘Recent’ defined as past 6 months

Odds Ratios

Confidence Interval

Adjusted Odds Ratios, Adjusted for all Sociodemographic and Polydrug use variables

‘Regular’ refers to daily or near daily use for 3 months or more

4. Discussion

The present study identified correlates of regular/heavy cigarette smoking among a large sample of 576 recent cocaine and heroin users. In support of the first hypothesis, the most commonly reported number of CPD was 20, suggesting “digit bias” (Klesges, et al., 1995; Shiffman, 2009). Evidence regarding the second hypothesis – generalization of cue reactivity of smoking from one substance to another – was ambiguous. Although there were differences by smoking status for the regular smoking of marijuana or crack, the differences were in unexpected directions. In both cases, more light smokers used regularly than both heavy smokers and non-smokers. Cocaine patients report that heavy cigarette smoking makes the regular smoking of other substances difficult due to the harshness of the smoke (Sees & Clark, 1993). This may interfere with the ability of stimulus generalization of cue reactivity to increase overall smoking. Further research is needed.

Although the hypothesized relationship was not found, regular/heavy smokers used a greater number of other substances and more heavy smokers have ever injected. Further, regular/heavy cigarette smokers were more likely to have regularly injected heroin. This is consistent with findings that current injection drug users (IDUs) smoke more than prior IDUs (Marshall, et al., 2011). The reason for this relationship is unclear. Heroin injection may be a particularly severe form of drug use that is associated with more severe behavior in general (Chun, et al., 2009; Gossop, Griffiths, Powis, & Strang, 1992). Controlling for various covariates helped to reduce this possibility, but may not have accounted for the true differences driving this relationship. Further research should examine this issue in other subgroups, such as prescription opioid users.

Alternatively, something specific about injection, opioid use, or injection heroin use may be uniquely associated with cigarette smoking. Injection of heroin leads to a larger subjective “high” than nasal heroin (Comer, Collins, MacArthur, & Fischman, 1999), and is more prevalent than smoking of heroin (SAMHSA, 2009). Only one person from the present sample reported ever smoking heroin regularly. Opiates such as heroin tend to increase cigarette smoking by human participants in experimental designs (Chait & Griffiths, 1984; Spiga, Martinetti, Meisch, Cowan, & Hursh, 2005). It is also possible that nicotine is useful in relieving pain associated with injection. Although the relationship between tobacco smoking and pain is complex, nicotine appears to relieve pain in humans (Shi, Weingarten, Mantilla, Hooten, & Warner, 2010). In animals, opioids and nicotine can cause cross-tolerance to pain-relieving effects (Biala & Weglinska, 2006; Pomerleau, 1998). Further research is needed, especially given the intertwined relationships between injection heroin use, HIV/AIDS, cigarette smoking, and increased mortality (Braithwaite, et al., 2005; Burkhalter, Springer, Chhabra, Ostroff, & Rapkin, 2005; Chaturvedi, et al., 2007; Engels, et al., 2006).

The study had some limitations. The data are cross-sectional, so no causal relationships can be established. Longitudinal and experimental research may provide better answers to questions about stimulus generalization. Additionally, further research in other areas is needed to see if our results are generalizable outside of Baltimore, MD. For example, the co-occurrence of heroin injection and cigarette smoking may be a cultural factor specific to Baltimore. Also, data were obtained by self-report, which may be limited by memory biases or trust issues. The urinalysis data, however, is consistent with self-report, and self-report is recognized as relatively reliable and valid (Darke, 1998; Shiffman, 2009).

There are several notable strengths. The inclusion of a large sample of a hard-to-reach group of heroin and/or cocaine users provided for advantages compared to prior literature. It permitted for detailed analysis of sociodemographics and the creation of multivariate models to explore potential confounders. We were able to examine adequate sample sizes of non-smokers, light smokers, regular smokers, and heavy smokers. Finally, this is the only study on illicit drug use and cigarette smoking of which we are aware that provides data on routes of administration for both cocaine and heroin, including heroin and/or cocaine users who have never injected either drug. Optimal prevention and treatment outcomes require a comprehensive understanding of the interrelations between different substances of abuse.

Highlights.

We examined correlates of cigarette smoking among heroin and cocaine users

Regular tobacco smokers more likely to be White, previously married, and uneducated

Marijuana and crack use associated with cigarette smoking, but not heavy smoking

Injection use was more common among heavy cigarette smokers

Tobacco smokers more likely to regularly inject heroin, even when covariate adjusted

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: This research was funded by a grant awarded to Willima Latimer from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA-R01 DA14498) and by the Drug Dependence Epidemiology Training Grant (NIDA T32 DA007292) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, William Latimer, Director. NIDA had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit for publication.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions to this research by the staff that currently work and have worked at the Neurocognitive and Behavioral Research Center, as well as the study participants without whom the research would not be possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: Author Harrell conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of this manuscript. Authors Trenz, Scherer, and Ropelewski have critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Author Latimer was the principal investigator of the study where these data were collected. All authors have approved of the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicting interests to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baca CT, Yahne CE. Smoking cessation during substance abuse treatment: what you need to know. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AE, Turner RJ. Family structure and substance use problems in adolescence and early adulthood: examining explanations for the relationship. Addiction. 2006;101:109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biala G, Weglinska B. On the mechanism of cross-tolerance between morphine- and nicotine-induced antinociception: involvement of calcium channels. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2006;30:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, Justice AC, Chang CC, Fusco JS, Raffanti SR, Wong JB, Roberts MS. Estimating the proportion of patients infected with HIV who will die of comorbid diseases. The American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118:890–898. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Hughes JR, Bickel WK. Nicotine and caffeine use in cocaine-dependent individuals. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5:117–130. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90056-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter JE, Springer CM, Chhabra R, Ostroff JS, Rapkin BD. Tobacco use and readiness to quit smoking in low-income HIV-infected persons. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2005;7:511–522. doi: 10.1080/14622200500186064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burling TA, Burling AS, Latini D. A controlled smoking cessation trial for substance-dependent inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait LD, Griffiths RR. Effects of methadone on human cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1984;229:636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi AK, Pfeiffer RM, Chang L, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ, Engels EA. Elevated risk of lung cancer among people with AIDS. AIDS. 2007;21:207–213. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280118fca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Haug NA, Guydish JR, Sorensen JL, Delucchi K. Cigarette smoking among opioid-dependent clients in a therapeutic community. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:316–320. doi: 10.1080/10550490902925490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JG, Stein MD, McGarry KA, Gogineni A. Interest in smoking cessation among injection drug users. The American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10:159–166. doi: 10.1080/105504901750227804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmey P, Brooner R, Chutuape MA, Kidorf M, Stitzer M. Smoking habits and attitudes in a methadone maintenance treatment population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;44:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Collins ED, MacArthur RB, Fischman MW. Comparison of intravenous and intranasal heroin self-administration by morphine-maintained humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;143:327–338. doi: 10.1007/s002130050956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson B, Hjalmarson A, Kruse E, Landfeldt B, Westin A. Effect of smoking reduction and cessation on cardiovascular risk factors. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2001;3:249–255. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels EA, Brock MV, Chen J, Hooker CM, Gillison M, Moore RD. Elevated incidence of lung cancer among HIV-infected individuals. Journal of Clinical Oncolology. 2006;24:1383–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Marrone GF, Heishman SJ, Schmittner J, Preston KL. Tobacco, cocaine, and heroin: Craving and use during daily life. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Bray JW, Pechacek T, Woollery T. Response by adults to increases in cigarette prices by sociodemographic characteristics. Southern Economic Journal. 2001;68:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Catalano RF. Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: an examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:153–167. doi: 10.1177/0022146510368930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Oesterle S, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Romantic relationship status changes and substance use among 18- to 20-year-olds. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:847–856. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Jiang L, Richter KP. Cigarette smoking cessation services in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Nahom D, Jarvik ME. Associations between tobacco smoking and illicit drug use among methadone-maintained opiate-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:97–103. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Stein JA, Shoptaw S. Using latent-variable models to analyze smoking cessation clinical trial data: an example among the methadone maintained. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10:258–267. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu SS, Kodl M, Willenbring M, Nelson DB, Nugent S, Gravely AA, Joseph AM. Ethnic differences in alcohol treatment outcomes and the effect of concurrent smoking cessation treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariti P, Alterman A, Mulvaney F, Mechanic K, Dhopesh V, Yu E, Chychula N, Sacks D. Nicotine intervention during detoxification and treatment for other substance use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:671–679. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godtfredsen NS, Prescott E, Osler M. Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:1505–1510. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Griffiths P, Powis B, Strang J. Severity of dependence and route of administration of heroin, cocaine and amphetamines. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1527–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Passalacqua E, Tajima B, Manser ST. Staff smoking and other barriers to nicotine dependence intervention in addiction treatment settings: A review. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:423–433. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Sorensen JL, Hall SM, Lin C, Delucchi K, Sporer K, Chen T. Cigarette smoking in opioid-using patients presenting for hospital-based medical services. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17:65–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490701756112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell PT, Montoya ID, Preston KL, Juliano LM, Gorelick DA. Cigarette smoking and short-term addiction treatment outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR, HowellWhite S. Becoming married and mental health: A longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:895–907. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:61–69. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Gomez-Dahl L, Kottke TE, Morse RM, Melton LJ., 3rd Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. Role of tobacco use in a community-based cohort. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275:1097–1103. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.14.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Willenbring ML, Nugent SM, Nelson DB. A randomized trial of concurrent versus delayed smoking intervention for patients in alcohol dependence treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:681–691. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesges RC, Debon M, Ray JW. Are self-reports of smoking rate biased - Evidence from the 2nd National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1995;48:1225–1233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn CS, Tsoh JY, Weisner CM. Changes in smoking status among substance abusers: baseline characteristics and abstinence from alcohol and drugs at 12-month follow-up. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E. Maturing out of substance use: Selection and self-correction. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Lee TC, Hanlon JG, Ben-David J, Booth GL, Cantor WJ, Connelly PW, Hwang SW. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in homeless adults. Circulation. 2005;111:2629–2635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Rothbard JC. Alcohol and the marriage effect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999:139–146. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MM, Kirk GD, Caporaso NE, McCormack MC, Merlo CA, Hague JC, Mehta SH, Engels EA. Tobacco use and nicotine dependence among HIV-infected and uninfected injection drug users. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Sellers ML, Kuehnle JC. Effects of heroin self-administration on cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980;67:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00427594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolchan ET, Fagan P, Fernander AF, Velicer WF, Hayward MD, King G, Clayton RR. Addressing tobacco-related health disparities. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 2):30–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieva G, Ortega LL, Mondon S, Ballbe M, Gual A. Simultaneous versus delayed treatment of tobacco dependence in alcohol-dependent outpatients. European Addiction Research. 2011;17:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000321256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampel FC. The persistence of educational disparities in smoking. Social Problems. 2009;56:526–542. [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Batra V, Mannelli P, Evers-Casey S, Vergare MJ, Leone FT. Medical symptoms associated with tobacco smoking with and without marijuana abuse among crack cocaine-dependent patients. American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14:43–53. doi: 10.1080/10550490590899844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Lundy A, Leone FT, Weinstein SP, Gottheil E, Steinberg M. Tobacco and alcohol use and medical symptoms among cocaine dependent patients. Substance Abuse. 2002;23:105–114. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky PF. Racial and ethnic differences in lung cancer incidence: how much is explained by differences in smoking patterns? (United States) Cancer Causes and Control. 2006;17:1017–1024. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF. Endogenous opioids and smoking: a review of progress and problems. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Ahluwalia HK, Mosier MC, Nazir N, Ahluwalia JS. A population-based study of cigarette smoking among illicit drug users in the United States. Addiction. 2002;97:861–869. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Badger GJ. A comparison of cocaine-dependent cigarette smokers and non-smokers on demographic, drug use and other characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;40:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satre DD, Kohn CS, Weisner C. Cigarette smoking and long-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes: a telephone follow-up at five years. American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:32–37. doi: 10.1080/10550490601077825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Grabowski J, Rhoades H. The effects of high and low doses of methadone on cigarette smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sees KL, Clark HW. When to begin smoking cessation in substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severtson SG, Mitchell MM, Hubert A, Latimer W. The relationship between performance on the Shipley Institute of Living Scale (SILS) and hepatitis C infection among active injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:61–65. doi: 10.3109/00952990903573264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lawrence D, Fagan P, Gibson JT. Racial/ethnic variation in cigarette smoking among the civilian US population by occupation and industry, TUS-CPS 1998–1999. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Weingarten TN, Mantilla CB, Hooten WM, Warner DO. Smoking and pain: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:977–992. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ebdaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. How many cigarettes did you smoke? Assessing cigarette consumption by global report, Time-Line Follow-Back, and ecological momentary assessment. Health Psychology. 2009;28:519–526. doi: 10.1037/a0015197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M, Singh GK, Jones PR, Timsina LR. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in duration of smoking: results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey. Journal of Public Health (Oxford) 2010;32:210–218. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M, Wakefield MA, Spittal MJ, Durkin SJ, Scollo MM. Taxation reduces social disparities in adult smoking prevalence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S, Ramos BM. Applying laboratory research: drug anticipation and the treatment of drug addiction. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10:162–183. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MS, Connett JE, Nides MA, Lindgren PG, Kleerup EC, Murray RP, Bjornson WM, Tashkin DP. Smoking reduction and the rate of decline in FEV(1): results from the Lung Health Study. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;25:1011–1017. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00086804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga R, Martinetti MP, Meisch RA, Cowan K, Hursh S. Methadone and nicotine self-administration in humans: a behavioral economic analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;178:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434) Rockville, MD: 2009. [accessed 10.02.10]. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k8nsduh/2k8Results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Temple MT, Fillmore KM, Hartka E, Johnstone B, Leino EV, Motoyoshi M. A metaanalysis of change in marital and employment status as predictors of alcohol-consumption on a typical occasion. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1269–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Sofuoglu M. The impact of cigarette smoking on stimulant addiction. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:12–17. doi: 10.1080/00952990802326280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Foulds J, Dwyer M, Order-Connors B, Springer M, Gadde P, Ziedonis DM. The integration of tobacco dependence treatment and tobacco-free standards into residential addictions treatment in New Jersey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]