Abstract

In this report we describe our ongoing target repurposing efforts focused on discovery of inhibitors of the essential trypanosomal phosphodiesterase TbrPDEB1. This enzyme has been implicated in virulence of Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of human African trypanosomiasis (HAT). We outline the synthesis and biological evaluation of analogs of tadalafil, a human PDE5 inhibitor currently utilized for treatment of erectile dysfunction, and report that these analogs are weak inhibitors of TbrPDEB1.

Keywords: Neglected disease, Trypanosoma brucei, Target repurposing, Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, TbrPDEB1, PDE5, tadalafil

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), is a significant neglected tropical disease. Currently, around 50 million people are at risk of contracting HAT, and annually the incidence of HAT infections is estimated at 50,000.1,2 The current therapies are severely limited by cost, route of administration, toxicity to the patient, and drug resistant trypanosomes.3 The genome of Trypanosoma brucei codes for five different PDEs, and two of these (TbrPDEB1 and TbrPDEB2) are closely related and demonstrated to be required for virulence.4,5 These enzymes have been demonstrated to be viable drug targets for trypanosomiasis.6-8

As a rapid and cost-effective approach to neglected tropical disease (NTD) drug discovery, we employ a “target repurposing” approach.9 This approach entails the identification of potential targets in the parasite that show homology to biological targets in humans that have already been pursued for drug discovery efforts. Knowledge from these drug discovery efforts can be repurposed in the design, synthesis, and optimization of new agents that inhibit the parasite targets. Furthermore, since the human homolog is likely to be a potential off-target in an antiparasitic treatment, previous knowledge about pharmacology of the lead molecule chemotype can be readily employed.

We describe in this article, and in the preceding article,10 a focus on the synthesis and assessment of analogs of established PDE5 inhibitors. We8 and others7,11 have shown that some human PDE inhibitors and their analogs display various degrees of inhibition towards the parasitic enzymes. We observed that tadalafil showed a lack of activity against TbrPDEB1 at 100 μM drug concentrations. Nevertheless, owing to the particularly extensive history in human PDE5 inhibitor medicinal chemistry, we were inclined to explore this chemotype by designing a variety of analogs based on the tadalafil scaffold. Furthermore, the tadalafil scaffold has been pursued by others as antimalarial lead compounds12 and trypanocides.13

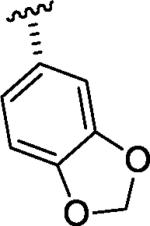

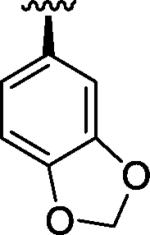

To guide our synthetic efforts we first considered the interactions made by tadalafil with human PDE5 that have been reported by others (Figure 1).14 In PDE5, the benzo[1,3]dioxole moiety points into a hydrophobic pocket that, based on homology modeling of the T. brucei enzymes, is predicted to be deeper.8 Such a pocket, referred to as the P- (or parasite) pocket, has also been demonstrated by X-ray crystallography to exist in the Leishmania major homolog, LmjPDEB1.15 The indole N-H interacts with the glutamine residue that is conserved across all known PDEs. The western end of tadalafil points towards a small lipophilic sub-pocket adjacent to the metal binding pocket in the human enzyme; our homology model of the parasitic enzyme suggests the presence of some polar amino acids in this region.8

Figure 1.

Putative position of tadalafil in the TbrPDEB1 binding site.

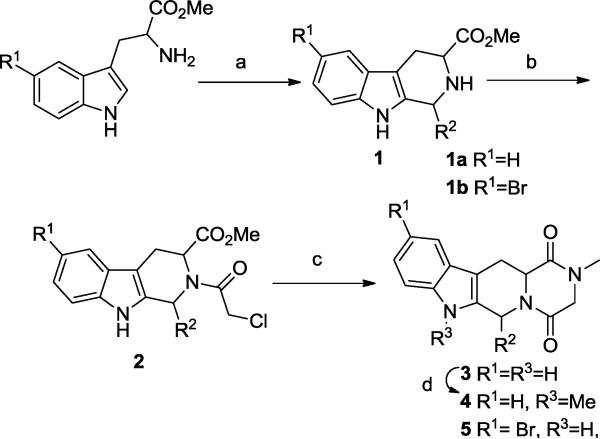

A handful of analogs that explored these regions were prepared (Scheme 1). Treatment of the appropriate tryptophan methyl ester under Pictet-Spengler conditions in the presence of the appropriate aldehydes provided intermediates 1. Then, acylation with chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine gave the chloroacetyl derivatives 2 in good yield. The piperazinedione derivatives 3 were obtained by reaction with methyl amine in refluxing methanol.

Scheme 1.

Conditions: (a) R2-CHO, CH2Cl2, CF3COOH, 0 °C to rt; (b) chloroacetyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2; (c) CH3NH2-HCl, MeOH, Et3N, reflux; (d) NaH, MeI, THF. (Refer to Table 1 for R2)

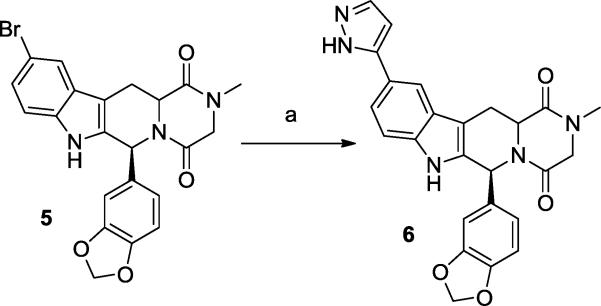

Preparation of N-methylated analogs of tadalafil and its C6 epimer was achieved by reacting the parent compound with sodium hydride and methyl iodide, giving 4a and 4b. The brominated analog 5 was prepared by applying the Scheme 1 reaction sequence, starting with 5-bromotryptophan. Compound 5 could be reacted under Suzuki conditions to provide the pyrazole analog 6 (Scheme 2). This sidechain was specifically selected among other options for its small size and H-bond donor-acceptor functionality, which may interact with the small polar pocket observed to be adjacent to the metal binding site.

Scheme 2.

Conditions: (a) 1H-pyrazol-5-ylboronic acid, aq. Na2CO3, Pd(dppf)Cl2, dioxane, 90 °C, overnight.

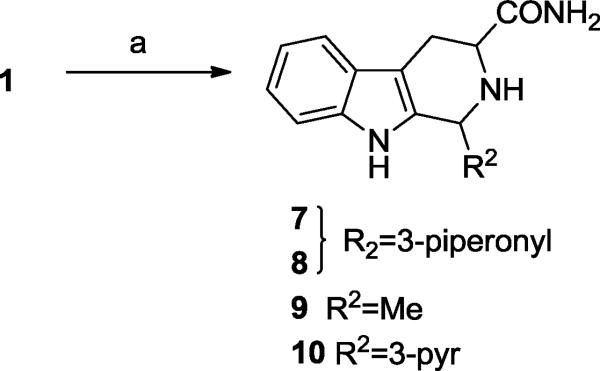

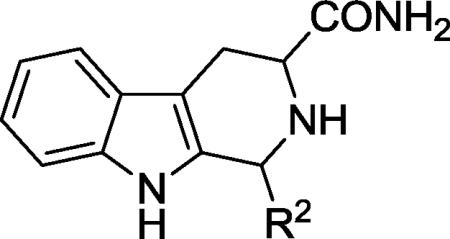

We also wished to explore the solvent-exposed region by truncation of the diketopiperazine moiety. This was achieved by treatment of intermediate 1 with ammonium hydroxide to give the tri-cyclic analogs 7-10 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

(a) NH4OH, Dioxane, rt.

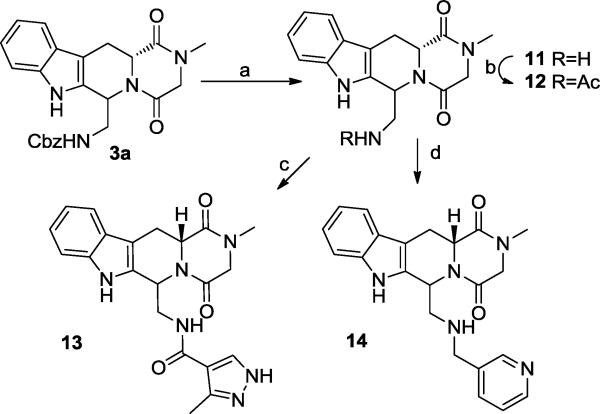

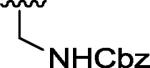

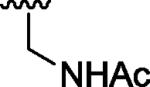

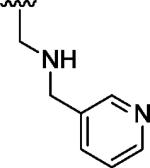

Additional analogs to explore the P-pocket region were synthesized by the sequence in Scheme 1, using CBZ-glycinal in the Pictet-Spengler reaction/cyclization sequence to give 3a. Deprotection of 3a (Scheme 4) by catalytic hydrogenation provided the amine template 11, that could be acylated (to provide 12 or 13) or alkylated (to provide 14). These analogs were designed in order to both probe the steric accessibility of the P- pocket, and to interact with the putative H-bond donors/acceptors present.

Scheme 4.

Conditions: (a) H2, Pd/C, EtOH, 3h; (b)Ac2O, DIEA, THF, 24h, rt; (c) 3-methyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxylic acid, EDC, Et3N, HOBt, CH2Cl2; (d) nicotinaldehyde, NaBH(OAc)3, THF/DMF, 48 h.

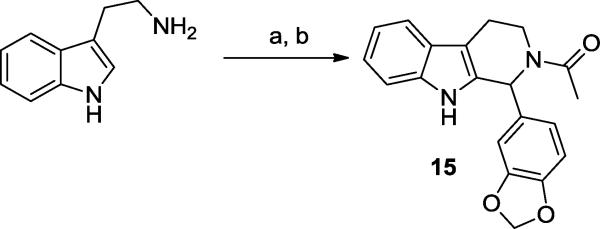

Finally, 15 was prepared in an analogous manner to the analogs shown in Scheme 1, starting from tryptamine.

All the tadalafil analogs synthesized were screened against TbrPDEB18 and the data is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The tricyclic analogs in Table 1 show weak activity. Although tadalafil showed no inhibition at 100 μM (Table 2) its C6 epimer 16 displayed almost 40% inhibition at the same concentration. Compound 15, showed very weak activity (17% inhibition). The other compounds in Table 2 show low-to-modest potency, including those that explored the putative P-pocket. However, compound 6, which was designed to interact with a small sub-pocket adjacent to the metal binding region displayed 72% inhibition at 10 μM. Unfortunately, a reliable dose-response experiment was not possible with this analog due to poor solubility at higher concentrations.

Table 1.

Potencies of tricyclic tadalafil analogs against TbrPDEB1.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R2 config | R2 | amide config | TbrPDEB1 (%inh)a |

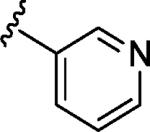

| 7 | α |

|

α | 19.5 |

| 8 | β |

|

α | 0 |

| 9 | α,β | CH3 | α,β | 13.3 |

| 10 | α,β |

|

α | 22.6b |

Inhibitor concentration 100.0 μM.

Inhibitor concentration 10.0 μM.

Table 2.

Tadalafil analogs tested against TbrPDEB1.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R2 | R3 | R1 | TbrPDEB1 (% inh)a |

| tadalafil |

|

H | H | 0b |

| 4a | CH3 | H | 6.9 | |

| 5a | H | Br | 11.8 | |

| 5 |

|

H | Br | 11.57 |

| 6 | H | 1H-pyrazol-3-yl | 71.8 | |

| 4b | CH3 | H | 19.7 | |

| 16 | H | H | 38.8 | |

| 3a |

|

H | H | 21.2 |

| 3b |

|

H | H | 9.4b |

| 12 |

|

H | H | 0 |

| 13 |

|

H | H | 0 |

| 14 |

|

H | H | 6.09 |

Inhibitor concentration 10.0 μM.

Inhibitor concentration 100.0 μM.

In conclusion, the goal of these experiments was to broadly explore the structure-activity relationships of the tadalafil scaffold. Most analogs synthesized displayed a poor inhibition profile with the notable exception of 6. Given the fairly flat SAR and low potencies observed, we confirm that the tadalafil scaffold does not hold as strong promise for potent TbrPDEB1 inhibitors as the PDE4 chemotypes previously disclosed.8

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5.

Conditions: (a) piperonal, CH2Cl2, CF3COOH, 0 °C to rt ; (b) acetyl chloride, Et3N, THF, rt.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI082577), Boston University and Northeastern University. We gratefully acknowledge a free academic license to the OpenEye suite of software.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting information

Full tabulation of all inhibitors prepared and screened in the context of this project is included in the supporting information, along with spectroscopic characterization of new compounds. Screening data from this overall TbrPDE inhibitor project will be made publically available as a public data set in the Collaborative Drug Discovery database (www.collaborativedrug.com).

References

- 1.Stuart K, Brun R, Croft S, Fairlamb A, Gurtler RE, McKerrow J, Reed S, Tarleton R. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1301. doi: 10.1172/JCI33945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brun R, Blum J, Chappuis F, Burri C. Lancet. 2010;375:148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matovu E, Seebeck T, Enyaru JCK, Kaminsky R. Microbes and Infection. 2001;3:763. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberholzer M, Marti G, Baresic M, Kunz S, Hemphill A, Seebeck T. FASEB J. 2007;21:720. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6818com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laxman S, Beavo JA. Mol Interv. 2007;7:203. doi: 10.1124/mi.7.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberholzer M, Marti G, Baresic M, Kunz S, Hemphill A, Seebeck T. FASEB J. 2007;21:720. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6818com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shakur Y, de KHP, Ke H, Kambayashi J, Seebeck T. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2011:487. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17969-3_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bland ND, Wang C, Tallman C, Gustafson AE, Wang Z, Ashton TD, Ochiana SO, McAllister G, Cotter K, Fang AP, Gechijian L, Garceau N, Gangurde R, Ortenberg R, Ondrechen MJ, Campbell RK, Pollastri MP. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:8188. doi: 10.1021/jm201148s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollastri MP, Campbell RK. Future Med. Chem. 2011;3:1307. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Ashton TD, Gustafson A, Bland ND, Ochiana SO, Campbell RK, Pollastri MP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.119. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seebeck T, Sterk GJ, Ke H. Future Med. Chem. 2011;3:1289. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beghyn TB, Charton J, Leroux F, Laconde G, Bourin A, Cos P, Maes L, Deprez B. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:3222. doi: 10.1021/jm1014617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deprez B, Beghyn T, Laconde G, Charton J. WO2008044144A2.

- 14.Sung BJ, Hwang KY, Jeon YH, Lee JI, Heo YS, Kim JH, Moon J, Yoon JM, Hyun YL, Kim E, Eum SJ, Park SY, Lee JO, Lee TG, Ro S, Cho JM. Nature. 2003;425:98. doi: 10.1038/nature01914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Yan Z, Geng J, Kunz S, Seebeck T, Ke H. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.