Abstract

The family of death domain (DD)-containing proteins are involved in many cellular processes, including apoptosis, inflammation and development. One of these molecules, the adapter protein MyD88, is a key factor in innate and adaptive immunity that integrates signals from the Toll-like receptor/interleukin (IL)-1 receptor (TLR/IL-1R) superfamily by providing an activation platform for IL-1R-associated kinases (IRAKs). Here we show that the DD-containing protein Unc5CL (also known as ZUD) is involved in a novel MyD88-independent mode of IRAK signaling that culminates in the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Unc5CL required IRAK1, IRAK4 and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 but not MyD88 for its ability to activate these pathways. Interestingly, the protein is constitutively autoproteolytically processed, and is anchored by its N-terminus specifically to the apical face of mucosal epithelial cells. Transcriptional profiling identified mainly chemokines, including IL-8, CXCL1 and CCL20 as Unc5CL target genes. Its prominent expression in mucosal tissues, as well as its ability to induce a pro-inflammatory program in cells, suggests that Unc5CL is a factor in epithelial inflammation and immunity as well as a candidate gene involved in mucosal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease.

Keywords: NF-kappaB, JNK, death domain, mucosal immunity, chemokines

The TLR/IL-1R superfamily of receptors has a fundamental role in shaping the immune response by integrating signals from pathogen-associated molecular patterns and the highly inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-18.1, 2 All of these receptors, with the prominent exception of TLR3, utilize the Toll–IL-1R (TIR) and death domain (DD)-containing adapter protein MyD88 to induce a signal transduction pathway that culminates in the activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Upon ligand-induced receptor dimerization, MyD88 is recruited to the cytosolic TIR domain via homotypic TIR–TIR interactions. This can either happen directly or via the adapter protein TIRAP/Mal. MyD88 then nucleates the assembly of a ternary protein complex via DD-dependent recruitment and activation of the kinases IRAK1, IRAK2 and IRAK4.8, 9 Together with the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 these factors mediate further propagation of the signal.10

The importance of the TLR/IL-1R signaling axis in health and disease is highlighted by the association with a multitude of human malignancies. These include not only the susceptibility of MyD88- and IRAK4-deficient patients to pyogenic bacterial infections, but also its implication in inflammatory disorders, autoimmunity and cancer.11, 12, 13

DD-containing proteins, including MyD88 and IRAKs, are also involved in many cellular signaling processes, including apoptosis, inflammation and development.14, 15 A functionally heterogeneous subgroup of these proteins is characterized by the presence of a tripartite domain module, termed the ZU5-UPA-DD supramodule, which in addition to a DD, contain a ZU5 (domain present in ZO-1 and Unc5) and a UPA (domain conserved in Unc5, PIDD and Ankyrin) domain.16 In mammals, this family comprises PIDD (p53-induced protein with a DD), Ankyrins1-3, the transmembrane receptors Unc5A-D and the poorly characterized protein Unc5CL (Figure 1a). Based on the resolution of the crystal structure of the intracellular part of Unc5B, Wang et al.16 proposed a conserved activation mechanism for these molecules, in which the ZU5 domain sequesters both the UPA and DD, keeping them in an auto-repressed state.

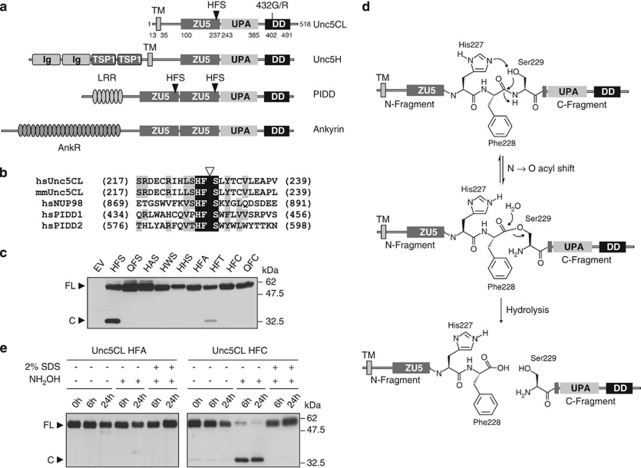

Figure 1.

Domain organization and autoproteolytic processing of Unc5CL. (a) Domain organization of ZU5-UPA-DD-containing proteins. (b) Multiple sequence alignment of the protein sequences of human (hs) and murine (mm) Unc5CL surrounding the putative autoproteolytic HFS site with the corresponding sequences from Nup98 and PIDD. Triangle: specific site of cleavage; black shading: identical amino acids; gray shading: similar amino acids. (c) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated C-terminally FLAG-tagged Unc5CL point mutants. FLAG-tagged proteins were analyzed by western blot. (d) Autoproteolytic cleavage mechanism at HFS sites. For autoproteolysis at the HFS site a three-step mechanism was proposed. First the histidine (His227) is involved in deprotonation of the hydroxyl group of the serine residue (Ser229). The serine hydroxyl group then functions as a nucleophile on the preceding amide bond, leading to an N → O acyl shift. The generated ester is then hydrolyzed, leading to cleavage between the phenylalanine and the serine residues. (e) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated C-terminally FLAG-tagged Unc5CL variants. FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated, eluted and incubated or not with 200 mM hydroxylamine (NH2OH) ±2% SDS as described for the indicated time points. Proteins were analyzed by western blot. (c and e) FL, Unc5CL full-length protein; C, Unc5CL C-terminal cleavage fragment

Unc5CL was proposed in a single study as a negative regulator of NF-κB in response to a variety of stimuli, including overexpression of TNF-R1, TRAF2, TRAF6, IKKβ and p65 or stimulation with TNFα and IL-1β.17 In sharp contrast to these previous observations, herein we identify Unc5CL as an inducer of a pro-inflammatory signaling cascade involving activation of NF-κB and JNK. Dissection of the pathway reveals a striking similarity to signaling events triggered downstream of TLR/IL-1R involving the kinases IRAK1, IRAK4 and the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRAF6, but surprisingly not the adapter protein MyD88 that is usually required for IRAK/TRAF6-dependent signaling. The protein shows a highly specific tissue distribution, predominantly detectable in samples of the uterus and small intestine. Furthermore, via an N-terminal transmembrane anchor, Unc5CL is associated specifically with the apical membrane of mucosal epithelial cells. Taken together, our results uncover evidence for a hitherto-unidentified pro-inflammatory signaling pathway in mucosal epithelial cells that provides a MyD88-independent second axis of IRAK-dependent signaling in parallel to the evolutionarily conserved TLR/IL-1R system. Its pro-inflammatory activity, as well as its strikingly specific tissue distribution in mucosal epithelia implicates Unc5CL as a novel candidate molecule in mucosal inflammation, immunity and disease.

Results

Domain organization of Unc5CL

Unc5CL was first described as a novel ZU5 and DD-containing protein mostly homologous to the intracellular fragments of the Unc5-receptor family members.17 Interestingly, the resolution of the X-ray crystal structure of the rat Unc5B intracellular domain revealed a tripartite domain organization comprising the previously described ZU5 and DD, as well as a novel central UPA domain.16 To evaluate whether Unc5CL also contains such a ZU5-UPA-DD supramodule we used Jpred3 to predict the secondary structure of Unc5CL and compared it with experimentally determined features of rat Unc5b intracellular domains (Supplementary Figure S1).18 Pairwise alignment using ClustalW revealed 34% sequence similarity.19 In addition, most of the secondary structures were conserved among the analyzed sequences. These observations provide evidence that Unc5CL indeed contains a ZU5-UPA-DD supramodule and we annotate the ZU5 from aa 100 to 237, the UPA from aa 243 to 385 and the DD from aa 402 to 491 (Figure 1a).

Further analysis using the transmembrane helix prediction tool TMHMM identified a previously unreported N-terminal transmembrane domain spanning aa 13–35 suggesting that Unc5CL is not a cytosolic, but membrane anchored protein (Figure 1a).20

We initially cloned the human Unc5CL cDNA from CaCo-2 cells (GenBank accession: JF681947) that corresponds to the current NCBI reference sequence (NM_173561.2). Interestingly, we observed that this sequence is different by one nucleotide from a cDNA used in a previous study on Unc5CL (GenBank: AY510109), corresponding to a nonsynonymous SNP variant (dbSNP ID: rs742493).17 This previously used variant contains a glycine at position 432 (432G) instead of a canonical arginine (432R) localized in the predicted second alpha helix of the DD (Figure 1a, Supplementary Figure S1). We therefore decided to include both Unc5CL 432G and 432R variants in our experiments.

PIDD is a ZU5-UPA-DD supramodule-containing protein that requires autoproteolytic processing at two core HFS tripeptide sites for its biogenesis and activation (Figure 1a).21 Cleavage at an HFS site is also involved in the biogenesis of the nuclear envelope protein Nup98.22 Surprisingly, by sequence comparison, we identified a bona fide HFS site in Unc5CL (aa 227–229) but not in any other ZU5-UPA-DD-containing proteins, suggesting that Unc5CL might also undergo such autoproteolytic cleavage (Figures 1a and b and Supplementary Figure S1).

Autoproteolytic processing of Unc5CL

When Unc5CL was expressed in HEK293T cells and analyzed by western blot we could detect a band corresponding to the full-length protein at approximately 58 kDa and a lower migrating band at approximately 32 kDa. These molecular weights correspond to the predicted size of the fragments that would be generated by cleavage of Unc5CL at the HFS site (Figure 1c). Indeed, expression of HFS point mutants impaired the appearance of the cleavage fragment of Unc5CL. Only a mutant carrying an HFT site still showed residual processing, which is consistent with the proposed requirements for this cleavage event (Figure 1d). To further corroborate the presence of an autoproteolytic HFS site in Unc5CL, we used a mutant where the serine of the HFS site is exchanged by a cysteine (HFC). Previous studies on Nup98 and PIDD have shown that this site can be cleaved involving formation of a thioester intermediate via an N → S acyl shift.21, 22 However, cleavage of the thioester intermediate requires addition of the nucleophilic agent hydroxylamine. To test whether Unc5CL HFC also forms a thioester intermediate, we analyzed the sensitivity to hydroxylamine-induced cleavage (Figure 1e). As expected, incubation of Unc5CL HFC with hydroxylamine induced the generation of the C-terminal cleavage fragment, which could be inhibited by pre-incubation with 2% SDS leading to protein denaturation. Taken together, these results provide evidence that, similar to Nup98 and PIDD, Unc5CL is autoproteolytically cleaved at an HFS site.

Membrane association and topology of Unc5CL

To corroborate that Unc5CL is a membrane integral protein, a TX-114 phase separation technique was applied.23 As expected, stably overexpressed Unc5CL variants with intact N-terminus (wt, ΔDD and S229A) were detected predominantly in the membrane fraction (Supplementary Figures S2a, b and d). Conversely, a mutant lacking the N-terminal transmembrane segment (ΔTM) was found in the hydrophilic fraction, indicating that this part of the protein mediates membrane association (Supplementary Figures S2a, b and d).

N-terminally anchored proteins can be inserted into membranes in two orientations. In type-II anchor proteins, the N-terminus remains in the cytosol and the C-terminus is translocated into the ER lumen, whereas in type-III anchor proteins the topology is reversed.24 In case of Unc5CL the charge distribution around the TM domain hints to a type-III topology (‘positive-inside rule' Supplementary Figure S2a).25 This was confirmed by proteinase K protection assays (Supplementary Figures S2a and c). These results confirm that Unc5CL is anchored with its N-terminus in the cell membrane with the C-terminus containing the DD exposed to the cytosol.

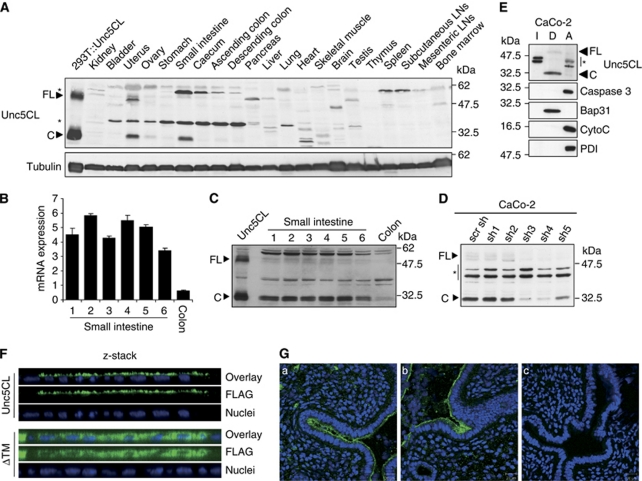

Tissue distribution and subcellular localization

Querying of the GNF1M mouse tissue atlas shows Unc5CL expression in the uterus, small intestine and thymus (Supplementary Figure S3).26 To confirm this on protein level, a mouse tissue panel was probed using antibodies against the DD of Unc5CL (Figure 2a). Consistent with the microarray data, Unc5CL protein was confined to the uterus, ovary and gastrointestinal tract, with prominent expression in the small intestine. Furthermore, the C-terminal cleavage fragment was readily detected in these tissues, indicating that the protein is efficiently and constitutively processed in vivo. The expression in the small intestine and colon could be further confined to the epithelial cells. Unc5CL protein and mRNA were enriched in epithelial cell preparations from consecutive small intestinal segments, and could also be detected in colonic epithelial cells, albeit to a lesser extent (Figures 2b and c). From the many cell lines that were tested for Unc5CL expression, only human colorectal CaCo-2 cells showed a convincing signal on western blots (Figure 2d). In line with the results observed in vivo, the C-terminal cleavage fragment was the prominent form detected. Specificity of the signal was confirmed by knockdown using Unc5CL-specific shRNAs (Figure 2d). As in HEK293T cells, Unc5CL was specifically found in the membrane fraction of CaCo-2 cells (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Tissue distribution and subcellular localization of Unc5CL. (A) Unc5CL-specific western blot of whole tissue lysates from the indicated tissues or overexpressed untagged Unc5CL as marker. (B) Relative Unc5CL mRNA expression in epithelial cell preparations from consecutive small intestinal (1–6) or colonic segments. Data represent the mean values ±S.D. of technical triplicates. (C) Unc5CL-specific western blot of intestinal (1–6) and colonic epithelial samples shown in (B). (D) Unc5CL-specific western blot of lysates from CaCo-2 cells stably expressing mock (scr sh) or Unc5CL-specific shRNAs (sh1–sh5). (E) Proteins from CaCo-2 cells were subjected to TX-114 phase separation. Fractions were analyzed by western blot using the indicated antibodies. CytoC, 14 kDa Cytochrome C, I, detergent-insoluble proteins, D, detergent phase, amphiphilic integral membrane proteins, A, aqueous phase, hydrophilic proteins. (F) z-stack reconstruction following confocal microscopy of overexpressed C-terminally FLAG-tagged Unc5CL (Unc5CL) or Unc5CL lacking the transmembrane domain (ΔTM) in CaCo-2 cells using FLAG-specific antibodies. (G) (a–c) Immunofluorescent staining of Unc5CL on cryosections from OCT embedded uterus using Unc5CL-specific antibodies. Blue: nuclear DAPI staining. (a, b) Green: Unc5CL, (c) isotype control (FLAG). (A, D and E) Asterisks mark unspecific bands

CaCo-2 cells form a polarized intestinal epithelium (including tight junctions and apical microvilli) when grown to post-confluence, and are a well-established model for intestinal physiology.27 We therefore decided to use these cells to determine the subcellular localization of Unc5CL. Interestingly, ectopic Unc5CL was detected predominantly in microvilli-like structures on the apical face, whereas a mutant lacking the transmembrane domain showed cytosolic distribution (Figure 2f; Supplementary Figure S4a). In line with this observation we found strong enrichment of Unc5CL in microvilli-derived murine intestinal brush border membrane vesicles (Supplementary Figures S4b and c). Immunohistochemistry using Unc5CL-specific antibodies suggests a similar apical epithelial localization in the uterine tissues (Figure 2g; Supplementary Figure S5).

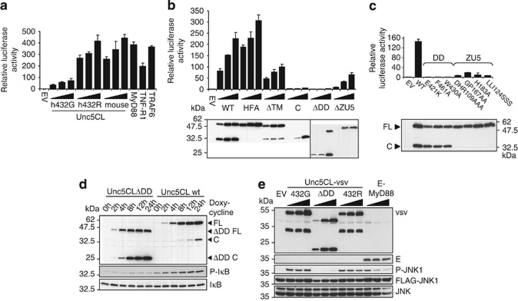

Unc5CL is an activator of NF-κB and JNK

Many DD-containing proteins are involved in signal transduction events leading to activation of NF-κB and JNK.14 As Unc5CL was previously implicated in the regulation of NF-κB, it was pertinent to re-evaluate these findings.17 In contrast to previous observations, overexpression of the two human variants, Unc5CL 432G and 432R, as well as murine Unc5CL led to a significant induction of NF-κB in a luciferase assay (Figure 3a). Interestingly, the 432G variant was less potent than the 432R or the corresponding murine form, indicating that this single amino-acid variation in the DD has an influence on protein activity. MyD88, TNF-RI and TRAF6 were used as positive controls for NF-κB activation. By using the same assay we determined domain requirements for Unc5CL-dependent NF-κB activation (Figure 3b). Firstly, an HFS to HFA mutant affecting the autoproteolytic cleavage site did not affect NF-κB activation, indicating that the cleavage event per se is not required. Deletion of the transmembrane domain (ΔTM) or the ZU5 domain (ΔZU5) showed an intermediate reduction in NF-κB activity, which is more pronounced using the C-terminal cleavage fragment only (C), where both of these domains are missing. Also co-expression of the N- and C-terminal cleavage fragments could not recapitulate the activity of the wild-type protein (Supplementary Figure S6). The strongest reduction in NF-κB activity was observed with a mutant lacking the DD (ΔDD), indicating that the NF-κB-inducing capacity of Unc5CL requires this domain. To further characterize the importance of the DD and ZU5 domains, we generated point mutants in highly conserved regions that were predicted to interfere with the function of these domains. In line with the results described above, destabilization of the DD completely abrogated NF-κB activating capacity, whereas ZU5 mutants retained very low activity (Figure 3c). Of note, mutations affecting the ZU5 domain also impair the ability for auto-processing, indicating that the cleavage requires a correct folding of this domain.

Figure 3.

Unc5CL is an activator of NF-κB and JNK. (a–c) HEK293T cells were transfected with NF-κB luciferase reporter gene plasmids together with an empty vector (EV) and increasing or single doses of the indicated expression constructs and were analyzed for NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity 24 h later. Data represent the mean values ±S.D. of technical triplicates; results are representative of three independent experiments. (b and c) The indicated expression constructs are based on Unc5CL genetic variant 432G. Proteins were analyzed by FLAG-specific western blot (d) HEK293 T-Rex cells stably containing doxycycline-inducible expression constructs for Unc5CL or Unc5CLΔDD were treated with 200 ng/ml doxycycline for the indicated time. Expression of FLAG-tagged constructs and phosphorylation of IκB were analyzed by western blot. (e) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with FLAG-JNK and the indicated constructs. Protein lysates were analyzed 24 h after transfection by western blot

NF-κB activation, as evidenced by phosphorylation of IκBα, was also observed in HEK293 T-Rex cells, in which Unc5CL expression is induced by addition of doxycycline (Figure 3d).

Signaling cascades leading to NF-κB activation often also activate the kinase JNK. When we tested Unc5CL for this capacity in an overexpression assay, we indeed observed that both Unc5CL 432G and 432R, but not the mutant lacking the DD, provoked the phosphorylation of co-expressed JNK1, confirming that Unc5CL is not only an activator of NF-κB but also of the kinase JNK (Figure 3e).

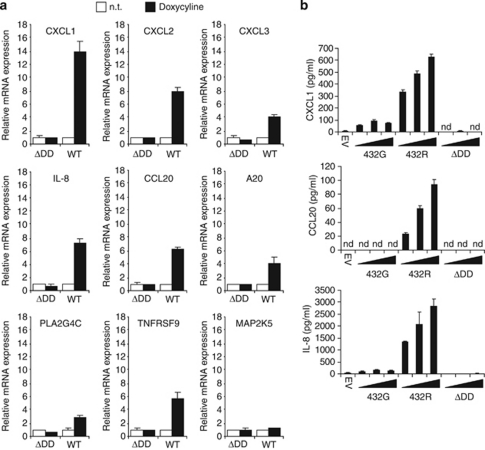

Transcriptional profiling identifies chemokines as Unc5CL targets

Several functions have been assigned to NF-κB, including induction of antiapoptotic and pro-inflammatory genes.28 The inducible HEK293 T-Rex cell line for Unc5CL described above was used in microarray experiments to determine genes that are transcriptionally regulated by Unc5CL overexpression. Interestingly, the most strongly induced genes, which were validated by real-time PCR, were chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, IL-8 and CCL20) and several other NF-κB-dependent genes (TNFAIP3/A20, PLA2G4C and TNFRSF9; Figure 4a).29 The expression of another gene, MAP2K5, was unaffected by Unc5CL. Secretion of CXCL1, IL-8 and CCL20 upon Unc5CL overexpression was confirmed by ELISA (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Unc5CL induces the expression and secretion of chemokines. (a) HEK293 T-Rex cells containing C-terminally FLAG-tagged Unc5CL (WT) or Unc5CLΔDD (ΔDD) were treated or not (n.t.) with 200 ng/ml doxycycline for 24 h. Cells were harvested and RNA was prepared. Changes in the relative expression of the indicated Unc5CL target genes were determined by real-time PCR. (b) HEK293T cells were transfected with increasing doses of the indicated expression constructs. Supernatants were analyzed 24 h later by ELISA for secretion of CXCL1, IL-8 and CCL20. (a and b) Data represent the mean values ±S.D. of technical triplicates; results are representative of three independent experiments

Unc5CL requires IRAK1, IRAK4 and TRAF6 but not MyD88 for NF-κB activation

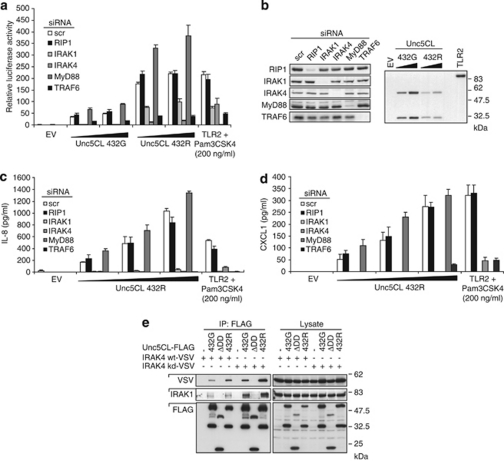

Several DD containing proteins have been identified as essential components of signaling pathways leading to NF-κB activation.14 RIP1 is implicated in NF-κB activation in response to TNFα.30 IRAK1, IRAK2 and IRAK4, together with the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRAF6, are involved in signaling downstream of most TLRs and IL-1R superfamily members.1, 2, 3 The adapter protein MyD88 links IRAK kinases to the respective receptors. To study the involvement of these proteins in Unc5CL-induced NF-κB activation, an siRNA approach was used. RIP1, IRAK1, IRAK4, MyD88 and TRAF6 were knocked down by transfection of gene-specific siRNAs, and the ability of Unc5CL to transactivate an NF-κB-specific luciferase reporter gene was assessed (Figures 5a and b). Although knockdown of RIP1 affected neither Unc5CL- nor TLR2-induced NF-κB, knockdown of IRAK1, IRAK4 and TRAF6 strongly impaired these signaling pathways. Moreover, knockdown of MyD88 only affected TLR2- but not Unc5CL-induced NF-κB activation, indicating that Unc5CL is involved in a novel IRAK-activating signaling cascade that uses the same signaling molecules as the TLR/IL-1R family. The same dependencies were observed for Unc5CL-mediated IL-8 and CXCL1 secretion (Figures 5c and d).

Figure 5.

Unc5CL-mediated NF-κB activation is IRAK-dependent but MyD88-independent. (a) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Forty eight hours later, cells were transfected with NF-κB luciferase reporter gene plasmids together with an empty vector (EV) and the indicated expression constructs and were analyzed for NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity 24 h later. TLR2-transfected cells were additionally treated with 200 ng/ml Pam3CSK4. (b) Selected protein samples from experiments shown in (a) were probed by western blot using the indicated antibodies. (c and d) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. 48 h later, cells were transfected with the indicated expression constructs and supernatants were analyzed for IL-8 and CXCL1 secretion by ELISA. TLR2-transfected cells were additionally treated with 200 ng/ml Pam3CSK4. (a, c and d) Data represent the mean values±S.D. of technical triplicates; results are representative of three independent experiments. (e) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated expression constructs. Immunoprecipitates and extracts were analyzed by western blot using the indicated antibodies

Interactions between MyD88 and IRAK kinases are mediated in a DD-dependent manner.8, 9 To test whether Unc5CL can also interact with IRAKs, co-immunoprecipitation experiments have been performed (Figure 5e). Wild-type or kinase-dead IRAK4 (IRAK4 kd) were co-expressed with Unc5CL 432G, Unc5CLΔDD or Unc5CL 432R. After immunoprecipitation of Unc5CL proteins, co-immunoprecipitation of overexpressed IRAK4 or endogenous IRAK1 was assessed. As expected, wild-type but not Unc5CLΔDD interacted with both IRAK4 and IRAK4 kd, as well as with endogenous IRAK1. Interestingly, Unc5CL variants 432G and 432R showed different affinities for IRAKs. Corresponding to the higher activity of Unc5CL 432R in NF-κB luciferase reporter assays, this variant showed higher capacity to co-immunoprecipitate IRAK1 and IRAK4. Different degrees of activity of Unc5CL 432G and 432R may therefore be attributed to different affinities of the respective DD for IRAKs.

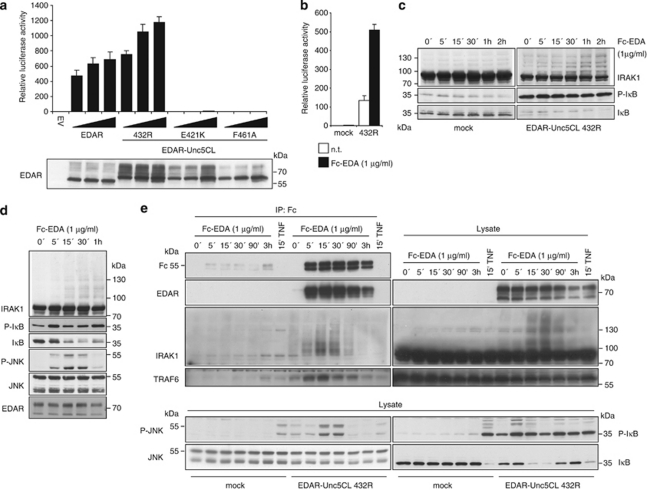

Ligand-induced activation of Unc5CL signaling using a chimeric receptor

As the activator of Unc5CL remains elusive, we created a fusion protein based on the DD-containing TNF receptor family member EDAR to gain insight into the mechanism of Unc5CL activation (Supplementary Figure S7). EDAR is particularly well suited for this purpose, as the endogenous protein is confined to the ectoderm during development, and not found on HEK293T cells.31, 32 The DD of EDAR was exchanged for the DD of Unc5CL 432R, or inactive point mutants E421K and F461A. In transient overexpression, the chimeric receptor containing the DD of Unc5CL 432R showed similar capacity as wild-type EDAR to activate NF-κB (Figure 6a). In contrast, chimeras containing the inactivating point mutations were not able to activate NF-κB, indicating that the NF-κB-activating ability of this chimeric receptor resides in the DD (Figure 6a). HEK293T cells stably expressing the chimeric receptor showed basal activation of NF-κB, which was enhanced by treatment with Fc-EDA (a hexameric form of the EDAR ligand that causes receptor clustering). This demonstrated proof-of-principle that signaling via the Unc5CL DD can be induced (Figure 6b). Basal activation was also reflected by constitutive phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα. (Figure 6c). Interestingly, we also observed reduced levels of IRAK1 protein in cells expressing the Unc5CL chimeric receptor than in the mock-infected cells (Figure 6c). Furthermore, treatment of these cells with Fc-EDA induced the appearance of higher molecular weight forms of IRAK1 (Figure 6c). These changes in IRAK1 most likely correlate with its activation.33 To more homogeneously activate the chimeric receptor, we identified a single-cell clone that showed low basal NF-κB activation, but which could be efficiently induced by the ligand Fc-EDA. In a time course experiment, Fc-EDA induced rapid phosphorylation of IκBα followed by its degradation (Figure 6d). In line with the observation that Unc5CL is an activator of JNK, we also observed efficient phosphorylation of this kinase. As observed in the pool of chimeric-receptor expressing cells, higher molecular weight forms of IRAK1 appeared throughout the stimulation. To study activation-induced recruitment of signaling molecules to the chimeric receptor we combined Fc-EDA stimulation with subsequent immunoprecipitation of the ligand (Figure 6e). As expected, Fc-EDA efficiently co-precipitated its receptor EDAR-Unc5CL. Moreover, modified forms of IRAK1 and TRAF6 were recruited to the complex in a time-dependent manner. Analysis of the whole cell lysate again confirmed inducible phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, phosphorylation of JNK and modification of IRAK1. Thus, ligand-induced oligomerization of the Unc5CL DD in the context of a receptor is sufficient to trigger signaling events that strongly resemble the MyD88-dependent branch of the TLR/IL1R family.

Figure 6.

Ligand-induced activation of Unc5CL signaling. (a) HEK293T cells were transfected with NF-κB luciferase reporter gene plasmids together with an empty vector (EV) or increasing or single doses of the indicated expression constructs and were analyzed for NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity 24 h later. 432R: EDAR-Unc5CL containing the Unc5CL DD variant 432R; E421K, F461A: EDAR-Unc5CL containing the Unc5CL DD with the indicated point mutations. The indicated expression constructs are based on Unc5CL genetic variant 432R. (b) Mock-infected or HEK293T cells ectopically expressing EDAR-Unc5CL were transfected with NF-κB luciferase reporter gene plasmids, were stimulated with 1 μg/ml Fc-EDA for 24 h and were analyzed for NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity. (a and b) Data represent the mean values ±S.D. of technical triplicates; results are representative of three independent experiments. (c) Mock-transduced HEK293T cells or HEK293T cells stably expressing chimeric EDAR-Unc5CL receptor were stimulated for the indicated time with 1 μg/ml Fc-EDA. Protein lysates were analyzed by western blot using the indicated antibodies. (d) Clonal HEK293T cells stably expressing chimeric EDAR-Unc5CL receptor were stimulated for the indicated time with 1 μg/ml Fc-EDA. Protein lysates were analyzed by western blot using the indicated antibodies. (e) Mock-transduced HEK293T cells or clonal HEK293T cells stably expressing chimeric EDAR-Unc5CL receptor were stimulated for the indicated time with 1 μg/ml Fc-EDA or Fc-TNF. Fc-EDA and associated proteins were precipitated from protein lysates using Protein G beads. Precipitated proteins (IP : Fc) or cell lysates (Lysate) were analyzed by western blot using the indicated antibodies

Discussion

In this study we found that Unc5CL is a novel inducer of a pro-inflammatory signaling cascade leading to activation of NF-κB and JNK. Dissection of the pathway identified the kinases IRAK1 and IRAK4, as well as the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 as essential downstream components. Most interestingly, MyD88, which is required for IRAK/TRAF6-dependent signaling downstream of IL-1- and Toll-like receptors, was dispensable for activity of Unc5CL. This finding indicates that Unc5CL provides a MyD88-independent second, parallel branch of the evolutionary conserved IRAK signaling cascade. While MyD88 is recruited to transmembrane receptors by virtue of its TIR domain, Unc5CL is already a membrane-anchored protein. Both proteins contain a DD that is required for interaction with members of the IRAK family.

An intriguing feature of Unc5CL is its highly specific tissue distribution in mucosal epithelia, most abundantly in the uterus and intestine. This site provides an interface between the inside and outside of the body where epithelia have an essential barrier function against invading pathogens.34 Interestingly, the protein is sorted to the apical face of these cells. In light of the pro-inflammatory signal that is triggered upon Unc5CL activation, and lack of an extracellular domain, it is valid to speculate that, similar to MyD88, Unc5CL is used as a membrane-bound adapter protein for a hitherto unknown receptor that is activated by a luminal factor. However, it cannot be excluded that Unc5CL is activated by an intracellular membrane-proximal signal.

Our experiments using a chimeric EDAR-Unc5CL receptor revealed that oligomerization of the Unc5CL DD is important for signal initiation, presumably by providing an assembly platform for IRAKs. We therefore postulate that oligomerization, which is required for MyD88-dependent signaling, is also a prerequisite for wild-type Unc5CL activity, and that this is stimulated by the putative upstream factor.

Transcriptional profiling identified mainly pro-inflammatory chemokines such as IL-8, CXCL1 and CCL20 as downstream targets of Unc5CL. These factors are well known to orchestrate the initial phase of an immune response by recruitment of immune cells including neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells and T cells to sites of potential danger.35 It is therefore possible that Unc5CL is involved in responses to epithelial danger.

Unc5CL is constitutively autoproteolytically processed at an HFS site that is also found in PIDD and Nup98.21, 22 While cleavage of the Nup98 precursor into mature nucleoporins Nup98 and Nup96 is required for its correct biogenesis and sorting to the nucleoplasmic side of the nuclear pore complex, inducible processing of PIDD is required for DNA damage-induced responses.21, 36, 37 Cleavage of Unc5CL appears constitutive and is not required for signaling, as evidenced by using a non-cleavable version (HFA). This hints to a role of Unc5CL autoprocessing in its biogenesis, localization or availability rather than activation, which should be addressed in future experiments.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, are chronic inflammatory disorders predominantly affecting the small and large intestine They are thought to arise from a complex interplay of environmental factors in a genetically predisposed host.38 Though many genetic linkage studies have revealed a number of genetic risk loci, identified genes can only be attributed to ca 10–20% of human cases. Unc5CL was previously identified as marker for IBD, together with several other genes that are transcriptionally upregulated in the diseased tissues (United States Patent no. 20100004213). Considering, in addition, the pro-inflammatory activity and the strikingly specific expression in mucosal epithelia, we propose Unc5CL as a putative candidate molecule causally involved in mucosal diseases such as IBD. This warrants investigation of Unc5CL in future genetic association studies.

Materials and Methods

Mice, cell culture and reagents

Six- to twelve-week-old mice were housed at the animal facility of the University of Lausanne. All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with Swiss federal legislation for animal experimentation. The human embryonic kidney HEK293T- and HEK293T-Rex cell lines (Invitrogen, Basel, Switzerland), were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). The human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line CaCo-2 was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 15% FCS and 1% MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen). All cells were maintained in the presence of 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Doxycyline, hydroxylamine and FLAG-peptide were obtained from Sigma (Buchs, Switzerland), Pam3CSK4 was from Invivogen (Nunningen, Switzerland). Fc-EDA and Fc-TNF were reported previously.32, 39

Antibodies

Monoclonal mouse anti-FLAG (M2) and anti-VSV (P5D4), as well as rabbit polyclonal anti-FLAG and anti-VSV were from Sigma; anti-Unc5CL (AT116) and anti-cytochrome C (7H6.2C12) were from Apotech (Epalinges, Switzerland); anti-Bap31 (CC-1) from Alexis (Lausen, Switzerland). Anti-phospho-IκB (# 9241) and anti-JNK (9252) from Cell Signaling (Allschwil, Switzerland); anti-phospho-JNK (44–682G) from Biosource (Basel, Switzerland); anti-IκB (sc-371), anti-MyD88 (sc-74532) and anti-IRAK1 (sc-7883) from Santa-Cruz (Nunningen, Switzerland); anti-RIP138 and anti-caspase-3 (46) from Transduction Laboratories (Allschwil, Switzerland); anti-IRAK4 from ProSci (Lausen, Switzerland) (3125); anti-TRAF6 from MBL (Nunningen, Switzerland) (597).

Expression plasmids and siRNA

Human Unc5CL 432R was amplified from a cDNA clone (GenBank: JF681947) by PCR and cloned in derivatives of pCR3 (Invitrogen), in frame with C-terminal FLAG and VSV tags. Unc5CL variant 432G was generated by site-directed mutagenesis with two sequential rounds of PCR (double PCR). Unc5CL point and deletion mutants were generated by PCR or double PCR. pCR3 plasmids expressing N-terminally VSV-tagged human IRAK4 or IRAK4 kd and pCAGGS-E-MyD88 were reported previously.40 Retroviral pMSCV plasmids, expressing Unc5CL and mutants, were generated by subcloning from pCR3, lentiviral pRDI_292 plasmids (a kind gift from R Iggo, University of St Andrews, Scotland) were generated by PCR. The packaging plasmids for pMSCV, pCG (encoding VSV G envelope glycoprotein) and pHit60 (encoding gag and pol retroviral genes) were kind gifts of CA Benedict (San Diego, CA, USA). Packaging plasmids for lentiviral gene transfer, pMD2.G and pCMVΔR8.91, were generously provided by Dr. Didier Trono. pcDNA5/FRT/TO plasmids (Invitrogen) for establishment of inducible HEK293 T-Rex cells were generated by subcloning from pCR3. The EDAR-Unc5CL fusion (EDAR aa 1–343, Unc5CL aa 402–518) was generated by double PCR and cloned in pCR3 or pMSCV. Derivatives corresponding to point mutations E421K and F461A were generated by double PCR. Lentiviral pLKO.1 plasmids expressing Unc5CL-specific shRNAs were obtained from Sigma. siRNAs were obtained from Ambion (Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Transfection, immunoprecipitation and western blot

Transfections were performed using the calcium-phosphate precipitation technique. Cells were usually lysed in Nonidet P (NP)-40 lysis buffer (0.1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaVO4, complete protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 15 min, 4°C. Murine tissue lysates were equally generated in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA and protease inhibitor mix) using a rotor-stator-type tissue homogeniser ART Miccra D-8 (Müllheim, Germany) (4 pulses of 10 s, 4°C).

Lysates were cleared by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge (13 000 r.p.m., 10 min, 4°C) and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Glattbrugg, Switzerland) and probed using the indicated antibodies.

siRNAs at final concentrations of 10 nM were also transfected into HEK293T cells using the calcium-phosphate precipitation technique.

For immunoprecipitation, 24 h after transfection cells were harvested and lysed as described above. Lysates were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 20 μl sepharose6B (Sigma) on a rotating wheel for a pre-clearing step. After centrifugation (5000 r.p.m., 1 min, 4°C) 1/10 supernatant (SN) was frozen (loaded as a cell extract control the following day) and 9/10 SN was immunoprecipitated O/N at 4°C on a rotating wheel, with 15 μl of a 1 : 2 mixture of FLAG M2-agarose beads (Sigma) and sepharose6B beads or 15 μl protein G beads. After extensive washing of the beads with lysis buffer the cell extracts and immunoprecipitates were loaded on a SDS-PAGE and the proteins were revealed by western blotting.

In vitro cleavage assays

HEK293T cells in 10 cm dishes were transfected with C-terminally FLAG-tagged expression vectors for Unc5CL that contain point mutations in the autoproteolytic HFS site (HFA, HFC). 24 h later cells were lysed and Unc5CL was immunoprecipitated as described above. FLAG-tagged proteins were washed and eluted by incubation for 10′ at RT with 120 μl 3 × FLAG peptide (Sigma, 100 μg/ml in lysis buffer). In all 20 μl of every eluate was kept for later analysis (0 h time point), the rest was divided in three parts. One part was left untreated, the other two were incubated with 200 mM hydroxylamine (NH2OH) with or without 2% SDS. 20 μl samples were taken at the indicated time points, mixed with SDS-sample buffer and analyzed by western blot.

Luciferase reporter assays

Cells in 24-well dishes were co-transfected in triplicate with 40 ng NF-κB firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs, in combination with 40 ng phRLTK (encodes a constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase), the indicated constructs, and an empty vector to normalize for the total quantity of 240 ng/well transfected DNA. 24 h after transfection, cells were either stimulated for the indicated periods or lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega, Dübendorf, Switzerland), and dual luciferase activity was measured in a Packard Top-Count NXT (PerkinElmer, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland) using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Triton X-114 phase separation

Triton X-114 (TX114) phase separation experiments were performed as described in Bordier.23 Briefly, 5 × 106 HEK293T cells stably expressing the indicated mutants were resuspended in 500 μl PBS and 100 μl 6% pre-condensed TX114, mixed by pipetting/inversion and incubated for 15 min on ice. The samples were centrifuged for 1 min at 13 000 r.p.m., the supernatants were transferred to new tubes, the pellets, which correspond to the insoluble fractions, were resuspended in 200 μl SDS-sample buffer by sonication. The supernatants were incubated for 5 min at 37°C to induce phase separation and centrifuged for 1 min at 13 000 r.p.m. at room temperature. The upper aqueous phases were transferred to new tubes. To wash, the lower, detergent phase was mixed with 500 μl PBS, the upper phase with 100 μl 6% TX114 and incubated for 5 min on ice and for 5 min at 37°C. Samples were centrifuged again and the initial phases were kept for further processing. Proteins were precipitated by adding 500 μl methanol and 125 μl chloroform to the aqueous phases and 450 μl PBS, 500 μl methanol and 125 μl chloroform to the detergent phases, followed by vortexing. Samples were centrifuged for 4 min at 13 000 r.p.m., 750 μl of the upper phases was removed and 400 μl methanol was added and mixed by pipetting. Samples were centrifuged again for 1 min at 13 000 r.p.m., supernatants were removed and the pellets were dried under the chemical hood. Precipitated proteins from the aqueous phase were resuspended in 200 μl, those from the detergent phase in 50 μl SDS-sample buffer. Proteins were solubilized by sonication and analyzed by western blot.

ELISA

Twenty four hours after transfection of HEK293T cells in 24-well plates, cell supernatants were analyzed for human CXCL1, CCL20 (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) and IL-8 expression (Immunotools, Friesoythe, Germany) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation of intestinal epithelial cells

The small intestine and colon were wholly dissected from euthanized C57BL/6 mice (6–12 weeks of age), cut in ca 3-cm sections, freed from residual feces and mucus after longitudinal section and transferred in ice-cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Invitrogen). After rinsing several times in HBSS at RT, residues were shaken gently in 15 ml of HBSS containing 2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 30 min at 37°C. The solid material was transferred to a new 50 ml tube containing 20 ml PBS and the supernatant was discarded. The remaining mucosa was vortexed vigorously and the supernatant containing complete crypts and some single cells were collected into a fresh 50 ml tube. Single cells and crypts were centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4°C.

Acknowledgments

We thank C Thomas for critically reading the manuscript and A Tardivel, S Hertig, G Guarda and TK Vogt for their technical help. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, NCCR Molecular Oncology, the EU-FP6 framework program RTN-ApopTrain, the Institute for Arthritis Research and Fondation Louis-Jeantet.

Author Contributions

LXH and JT designed research; LXH, MR, DCR, FS, KS, MQ, OG and PS performed the experiments; LXH, KS and OG analyzed the data; LXH and JT wrote the paper.

Glossary

- DD

death domain

- EDA

ectodysplasin-A

- EDAR

ectodysplasin-A receptor

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IκB

inhibitor of kappa B

- IKKβ

IκB kinase beta

- IL-1R

interleukin (IL)-1 receptor

- IRAK

IL-1R-associated kinase

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- Nup98

nuclear pore complex protein 98

- PIDD

p53-induced protein with a DD

- PLA2G4C

phospholipase A2 group IVC

- TIR

Toll–IL-1R domain

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TM

transmembrane

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TNFAIP3

TNF alpha-induced protein 3

- TNF-RI

tumor necrosis factor receptor type I

- TNFRSF9

TNF receptor superfamily member 9

- TRAF6

TNF receptor-associated factor 6

- Unc5CL

Unc5C-like protein

- UPA, domain found in Unc5

PIDD and Ankyrins

- ZU5

domain found in ZO-1 and Unc5

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by G Melino

Supplementary Material

References

- O'Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: 10 years of progress. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzio M, Ni J, Feng P, Dixit VM. IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science. 1997;278:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesche H, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, Li S, Cao Z. MyD88: an adapter that recruits IRAK to the IL-1 receptor complex. Immunity. 1997;7:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns K, Martinon F, Esslinger C, Pahl H, Schneider P, Bodmer JL, et al. MyD88, an adapter protein involved in interleukin-1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12203–12209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Kopp E, Stadlen A, Chen C, Ghosh S, et al. MyD88 is an adaptor protein in the hToll/IL-1 receptor family signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 1998;2:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motshwene PG, Moncrieffe MC, Grossmann JG, Kao C, Ayaluru M, Sandercock AM, et al. An oligomeric signaling platform formed by the Toll-like receptor signal transducers MyD88 and IRAK-4. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25404–25411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Lo YC, Wu H. Helical assembly in the MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK2 complex in TLR/IL-1R signalling. Nature. 2010;465:885–890. doi: 10.1038/nature09121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Xiong J, Takeuchi M, Kurama T, Goeddel DV. TRAF6 is a signal transducer for interleukin-1. Nature. 1996;383:443–446. doi: 10.1038/383443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Huang J, Gong W, Iribarren P, Dunlop NM, Wang JM. Toll-like receptors in inflammation, infection and cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1271–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard C, von Bernuth H, Ghandil P, Chrabieh M, Levy O, Arkwright PD, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with IRAK-4 and MyD88 deficiency. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89:403–425. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181fd8ec3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HH, Lo YC, Lin SC, Wang L, Yang JK, Wu H. The death domain superfamily in intracellular signaling of apoptosis and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:561–586. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC, Doctor KS, Godzik A. The domains of apoptosis: a genomics perspective. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:re9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2392004re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Wei Z, Jin H, Wu H, Yu C, Wen W, et al. Autoinhibition of UNC5b revealed by the cytoplasmic domain structure of the receptor. Mol Cell. 2009;33:692–703. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xu LG, Han KJ, Shu HB. Identification of a ZU5 and death domain-containing inhibitor of NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17819–17825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C, Barber JD, Barton GJ. The Jpred 3 secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36 (Web Server issue:W197–W201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinel A, Janssens S, Lippens S, Cuenin S, Logette E, Jaccard B, et al. Autoproteolysis of PIDD marks the bifurcation between pro-death caspase-2 and pro-survival NF-kappaB pathway. EMBO J. 2007;26:197–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum JS, Blobel G. Autoproteolysis in nucleoporin biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11370–11375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordier C. Phase separation of integral membrane proteins in Triton X-114 solution. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1604–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiess M. Heads or tails--what determines the orientation of proteins in the membrane. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:76–79. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00551-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltzer JP, Fiedler K, Fuhrer C, Geffen I, Handschin C, Wessels HP, et al. Charged residues are major determinants of the transmembrane orientation of a signal-anchor sequence. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:973–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su AI, Wiltshire T, Batalov S, Lapp H, Ching KA, Block D, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier V, Bourrie M, Berger Y, Fabre G. The human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2; pharmacological and pharmacokinetic applications. Cell Biol Toxicol. 1995;11:187–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00756522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting AT, Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. RIP mediates tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 activation of NF-kappaB but not Fas/APO-1-initiated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6189–6196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurikkala J, Pispa J, Jung HS, Nieminen P, Mikkola M, Wang X, et al. Regulation of hair follicle development by the TNF signal ectodysplasin and its receptor Edar. Development. 2002;129:2541–2553. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossen C, Ingold K, Tardivel A, Bodmer JL, Gaide O, Hertig S, et al. Interactions of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptor family members in the mouse and human. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13964–13971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamin TT, Miller DK. The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase is degraded by proteasomes following its phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21540–21547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribar SC, Richardson WM, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. No longer an innocent bystander: epithelial toll-like receptor signaling in the development of mucosal inflammation. Mol Med. 2008;14:645–659. doi: 10.2119/2008-00035.Gribar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola A, Luster AD. Chemokines and their receptors: drug targets in immunity and inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:171–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.121806.154841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontoura BM, Blobel G, Matunis MJ. A conserved biogenesis pathway for nucleoporins: proteolytic processing of a 186-kilodalton precursor generates Nup98 and the novel nucleoporin, Nup96. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1097–1112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S, Tinel A, Lippens S, Tschopp J. PIDD mediates NF-kappaB activation in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2005;123:1079–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaide O, Schneider P. Permanent correction of an inherited ectodermal dysplasia with recombinant EDA. Nat Med. 2003;9:614–618. doi: 10.1038/nm861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns K, Janssens S, Brissoni B, Olivos N, Beyaert R, Tschopp J. Inhibition of interleukin 1 receptor/Toll-like receptor signaling through the alternatively spliced, short form of MyD88 is due to its failure to recruit IRAK-4. J Exp Med. 2003;197:263–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.