Abstract

Purpose

To study the therapeutic effects of probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and identify subgroups benefiting most.

Background

Some trials investigating therapeutic effects in irritable bowel syndrome have shown benefits in IBS subgroups only. Probiotic treatment seems to be promising.

Methods

Patients with irritable bowel syndrome (120; Rome II) were recruited to a prospective double-blind study and randomized to either EcN (n = 60) or placebo (n = 60) given for 12 weeks. Objectives were to describe efficacy and safety of EcN in different groups of irritable bowel syndrome. Outcome was assessed by ‘Integrative Medicine Patient Satisfaction Scale’.

Results

Altogether, the responder rate was higher in the EcN than in the placebo group. However, only after 10 and 11 weeks, the differences were significant (Δ 20.0% points [95% CI 2.6; 37.4], p = 0.01 and Δ 18.3% points [95% CI 1.0; 35.7], p = 0.02, respectively). The best response was observed in the subgroup of patients with gastroenteritis or antibiotics prior to irritable bowel syndrome onset (Δ 45.7% points, p = 0.029). No significant differences were observed in any other subgroup. Both treatment groups showed similar adverse events and tolerance.

Conclusions

Probiotic EcN shows effects in irritable bowel syndrome, especially in patients with altered enteric microflora, e.g. after gastroenterocolitis or administration of antibiotics.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Treatment, Probiotics, E. coli Nissle 1917, Enteric infections

Introduction

Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are frequent among the general population, and they often give reason to seek for health care. However, individual treatment may be cumbersome and needs to be improved. Because of negative results of some trials, recent efforts focused upon therapeutic studies in selected groups of patients, such as patients with diarrhea or constipation predominant IBS or female patients [1].

The etiology of IBS is still not understood. Pathophysiological factors which are thought to play a role comprise alterations of the intestinal milieu, immune activation, enteric neuromuscular dysfunction and brain–gut axis dysregulation. All of these factors are influenced by enteric microbiota [2]. A recent metaanalysis suggests favorable therapeutic effects of probiotics in IBS [3].

Probiotic microorganisms have been defined as live microbes that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host [4, 5]. A particularly well-investigated probiotic strain is Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (serotype O6:K5:H1) (EcN). For example, its genomic sequence, the unique lipopolysaccharide and several of its microbiological properties are defined [6–8]. EcN is the active substance of the registered probiotic drug MUTAFLOR®. Moreover, in controlled studies, EcN has demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in functional constipation [9], diarrhea [10, 11] and also in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis [12]. Therefore, here, a study is presented, which investigated the therapeutic effects of EcN in patients with IBS. The specific purpose of the study was to identify subgroups of IBS patients benefiting from probiotic treatment with EcN.

Patients and methods

Definitions

IBS was defined according to the Rome II criteria [13]: within the last 12 months, at least 12 weeks (not necessarily consecutive) of abdominal pain or discomfort and at least two of the following criteria: (1) relief after defecation and/or (2) onset associated with a change in frequency of stools and/or (3) onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stools.

In addition, organic disease was excluded by using the Kruis score [14].

Participants

Patients were included in the study if they fulfilled the Rome II criteria [13] and if they had a sum of at least 26 points in the Kruis score. At the time of recruitment, patients between 18 and 65 years had to suffer from at least three of the following symptoms: diarrhea, constipation, urgency, abdominal pain, meteorism, flatulence, abdominal distension, feeling of fullness, borborygmi and/or nausea. Postinfectious IBS was defined as bacterial intestinal infection before the occurrence of IBS symptoms.

Specific exclusion criteria were organic intestinal disease, significant intestinal surgery, functional diarrhea or constipation not addressed by the definition of IBS and regular use of laxatives or antidiarrheals, antibiotics, chronic steroids or immunosuppressants.

Subjects seeking relief of their intestinal complaints were invited to participate by advertisements in local newspapers. After general and individual information by the attending physician (S. Chrubasik), suitable patients gave their written informed consent and were randomized.

Study design

The trial was designed as a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, monocenter study. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki (revised version of South Africa, 1996) and the Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice CPMP/ICH/135/95, 1996. Sponsorship was given by an unrestricted grant from Ardeypharm GmbH, Herdecke, Germany. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Deutsche Ärztekammer Nordrhein and registered with the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (the German regulatory authority). The study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (registration number DRKS00000416).

Patients were centrally randomized and allocated 1:1 to receive either one capsule MUTAFLOR® (with 2.5–25 × 109 CFU Escherichia coli Nissle 1917) o.d. for 4 days and thereafter two capsules MUTAFLOR® o.d. throughout the trial (n = 60 patients) or placebo in an identical shape and order of application (n = 60 patients). The study medication was given for 12 weeks.

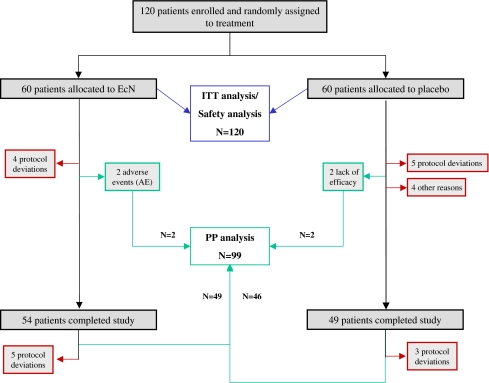

Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 120 subjects were enrolled, and all received at least one dose of study medication. Thus, the intention-to-treat population (ITT) comprised 120 patients for the efficacy and safety evaluation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient disposition by treatment group (all randomized patients, n = 120)

Objectives/outcome

The primary objective of the study was to describe the treatment effects of EcN in different groups of IBS and to compare the contentment of the patients with the treatment between the two groups receiving either EcN or placebo.

In addition, secondary efficacy variables included quality of life and changes in symptoms such as stool frequency and consistency, urgency, pain frequency and intensity, flatulence, distension and nausea. Also, drug safety and tolerance were monitored throughout the study.

Clinical evaluation

Clinic visits were appointed for weeks 0, 4, 8 and 12 or at termination of the study. Therapeutic success and safety were assessed according to diaries filled in by patients through the study. The primary endpoint was defined by global rating using the ‘Integrative Medicine Patient Satisfaction Scale’ (IMPSS) [15]. IMPSS offers five answers of the patient's contentment with therapy: very much satisfied, little satisfied, undecided, little dissatisfied and very much dissatisfied. The first two categories (very much satisfied and little satisfied) were regarded as successful treatment (‘responder’).

Quality of life was determined by using a health-related quality of life (HRQL) scoring system for patients with IBS [16]. This questionnaire comprises a range of 26 items with response options on a seven-point rating scale. The items contribute to four domains as follows: bowel symptoms, fatigue, activity limitations and emotional function.

Safety was assessed by recording all adverse events according to Good Clinical Practice for clinical trials of medication in the European Community (91/507/EWG, CPMP/ICH/135/95). Tolerance of the study medication was assessed by a four-point scale (very good, good, fair and poor), and the patient's compliance was checked by pill counting and the patient's diary. Laboratory analyses, including CRP, hemoglobin, blood cell count, hematocrit, ALT, AST, creatinine, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, were performed at the beginning and end of the study.

Study medication

The investigational drug was an enteric-coated capsule, containing 2.5–25 × 109 viable cells of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 (MUTAFLOR®, manufactured by Ardeypharm GmbH, Herdecke, Germany). The placebo was a capsule not distinguishable from the verum but without the active substance EcN. Concomitant medication with possible effects on gastrointestinal function (according to a given list) was not allowed. The compliance with the study medication was assessed according to pill counting.

Statistics

This trial was designed as an explorative study in order to test for therapeutic efficacy (in all patients and subgroups), safety and tolerance of EcN in patients with IBS. Because of the explorative approach of the study (with the objective of generating hypotheses), a sample size calculation was not performed.

In accordance with the design of the study, comparison of the treatment regimens was carried out by means of descriptive statistical methods. For the purpose of efficacy analysis, two data sets were defined, the intention-to-treat (ITT) sample and the per-protocol (PP) sample. The ITT population includes all patients enrolled (n = 120) because all participants received at least one dose of the study medication. After exclusion of 21 patients, the PP analysis set consisted of 99 patients. The most frequent exclusion criteria were major protocol deviations (17 patients) and premature study termination (4 patients) (Fig. 1). Additionally, subgroup analyses were planned. Chi-square test (one-sided, α = 0.05) was used for explorative investigation of all efficacy parameters on whether or not a difference existed between the two treatment groups. In general, data are given as mean ± SD and have 95% confidence intervals ([95% CI]).

The randomization schedule was generated by means of SAS®, version 8.2, based on a seed depending random number generator. The method of randomly permuted blocks was used (block size 4). Statistical evaluation was performed by an independent institution (ClinResearch GmbH, Cologne, Germany) using the program package SAS®, version 8.2.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the ITT population (n = 120) are listed in Table 1. The majority of the patients were female (76.6%). In general, patient demographics were well comparable between the two treatment groups. Of the 60 patients, 6 patients (10%) under EcN and 11 patients (18%) under placebo left the study before week 12. The following reasons were stated (multiple reasons possible): inclusion criteria not met (n = 9), non-tolerable adverse events (n = 3), lack of efficacy (n = 2), newly appeared exclusion criteria (n = 2) and personal reasons (n = 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and other baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study (intention to treat analysis)

| EcN group mean ± SD or number of patients (%) | Placebo group mean ± SD or number of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 60 | 60 |

| Females | 48 (80%) | 44 (73.3%) |

| Males | 12 (20%) | 16 (26.7%) |

| Age [years] | 46.3 ± 12.1 | 45.1 ± 12.7 |

| Duration of symptoms [years] | 12.3 ± 11.5 | 11.7 ± 12.0 |

| Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome known since [years] | 1.1 ± 3.0 | 1.3 ± 3.2 |

| Gastroenteritis and/or antibiotics prior to onset of symptoms | 10 (16.7%) | 7 (11.6%) |

| Constipation predominanta | 19 (31.7%) | 16 (26.7%) |

| Diarrhea predominanta | 27 (45.0%) | 27 (45.0%) |

| Alternating stool habitsa | 34 (56.7%) | 37 (61.7%) |

| Abdominal paina | 31 (51.7%) | 34 (56.7%) |

| Meteorisma | 50 (83.3%) | 56 (93.3%) |

| Flatulencea | 51 (85.0%) | 52 (86.7%) |

EcN Escherichia coli Nissle 1917

aPresent at inclusion into the study

Primary objectives

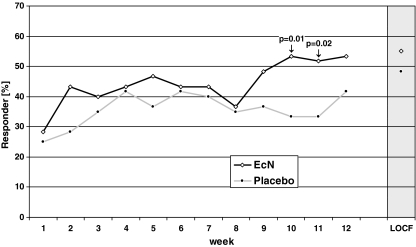

Clinical response curves for the ITT population are depicted in Fig. 2. The greatest difference between response rates in comparison to placebo occurred after 10 weeks, with a difference of 20.0% ([2.6; 37.4], p = 0.01), and after 11 weeks of treatment, with an 18.3% difference ([1.0; 35.7], p = 0.02). At the end of the study, the difference between the groups (EcN 53.3%, placebo 41.7%) was 11.6% ([−6.1; 29.4]) and did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.10).

Fig. 2.

Rate of overall responders during the 12-week treatment period (n = 120, intention to treat analysis)

After 12 weeks, 27 of the 51 patients (52.9%) achieved clinical response in the EcN group, and 23 of the 48 patients (47.9%) achieved clinical response in the placebo group (PP analysis, p = 0.30).

Subgroup analyses

Altogether, females showed higher response rates than males (females 51.1% vs. males 35.7% at week 12), but differences between the effects of EcN and placebo were similar in females (10.8%) and males (10.4%) after 12 weeks.

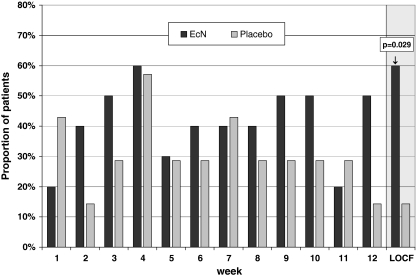

Additional subgroups, classified to the predominant symptom at the time of inclusion or according to the patient's case history, were analyzed (Table 2). The best therapeutic gain of EcN was observed in patients with prior bacterial intestinal infection (n = 5) (p = 0.01) as compared to placebo. Another 15 patients were given antibiotics prior to the onset of IBS symptoms. Summing up these patients with an altered enteric microflora (prior antibiotics and/or gastroenteritis; multiple entries possible) (n = 17), the difference in the treatment response between EcN and placebo was 45.7% (p = 0.029; Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Responders in subgroups after 12-week treatment (intention to treat analysis, chi- square test, last observation carried forward (LOCF))

| Definition of subgroups | Rate of responder | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| EcN group [%] | Placebo group [%] | p-value (one sided) | |

| Gastroenteritis and/or antibiotics prior to onset of symptoms | 60.0 | 14.3 | 0.0297 |

| Constipation predominanta | 57.9 | 50.0 | 0.3202 |

| Diarrhea predominanta | 51.9 | 51.9 | 0.5000 |

| Alternating stool habitsa | 61.8 | 48.6 | 0.1336 |

| Abdominal paina | 54.8 | 50.0 | 0.3482 |

| Meteorisma | 58.0 | 48.2 | 0.1568 |

| Flatulencea | 54.9 | 44.2 | 0.1394 |

| Urgencya | 55.6 | 50.0 | 0.3208 |

| Nauseaa | 63.2 | 50.0 | 0.2249 |

EcN Escherichia coli Nissle 1917

aPresent at inclusion into the study

Fig. 3.

Therapeutic success in patients with antibiotic pretreatment and/or postinfection (n = 17, intention to treat analysis, chi- square test, one-sided)

Therapeutic effects on symptoms recorded throughout the study

Changes of individual symptoms are depicted in Table 3. In both treatment arms, many symptoms improved during the study. Of particular interest are the highly significant effects on all qualities of pain such as intensity, duration and frequency. To note, meteorism and nausea showed significant improvements only with EcN.

Table 3.

Secondary parameters prior to study and after 12-week treatment (intention to treat analysis)

| Parameter | EcN group mean or number of patients (%) | Placebo group mean or number of patients (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to studya | Week 12 (LOCF) | p-value | Prior to studya | Week 12 (LOCF) | p-value | |

| Number of stools per week | 15.4 | 11.9 | 0.0545 | 12.6 | 10.3 | 0.0198 |

| Consistency of stool as deviation from value 4 = smooth (1 = hard, 7 = watery) | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.0023 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.0184 |

| Flatulence (0 = none, 1 = little, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) | 2.0 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 2.0 | 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Meteorism (yesb) | 85.0% | 66.7% | 0.0164 | 83.3% | 80.0 | 0.5637 |

| Urgency (yesb) | 46.7% | 51.7% | 0.5316 | 58.3% | 56.7% | 0.8185 |

| Nausea (yesb) | 43.3% | 23.3% | 0.0073 | 30.0% | 28.3% | 0.7630 |

| Pain ‘intensity’c | 61.2 | 80.2 | <0.0001 | 62.5 | 79.3 | <0.0001 |

| Pain ‘duration’c | 62.9 | 81.0 | <0.0001 | 63.4 | 78.7 | 0.0002 |

| Pain ‘frequency’c | 59.8 | 81.2 | <0.0001 | 61.4 | 78.9 | 0.0001 |

EcN Escherichia coli Nissle 1917, LOCF last observation carried forward

aData from week before starting treatment

bYes = at least one answer ‘yes’ per week

cPain scale from 0 = ‘very strong’ to 100 = ‘no pain’

Quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) improved in both treatment arms. The baseline score of the EcN group was 111.6 ± 22.2 and improved by 22.8 ± 28.7 points (20.4%). The respective numbers of the placebo group were 113.8 ± 22.3 (baseline score) and 20.0 ± 29.3 (improvement) (17.6%).

Safety and tolerance of the study medication

As rated by the patients, overall tolerance was ‘very good’ or ‘good’ in 91.7% of the patients in the EcN group as compared to 83.3% in the placebo group.

No deaths occurred during this study. Only one adverse event (AE), a tooth abscess in a patient of the placebo group, was classified as ‘serious’ due to the necessity for hospitalization.

A total of 57/120 patients (47.5%) experienced at least one AE, with 30/60 patients (50%) in the EcN group and 27/60 patients (45.0%) in the placebo group. The most frequent AE was influenza-like illness (6.7% in both treatment groups). In general, both treatment groups were similar with respect to the type and frequency of AEs. No unexpected alterations were detected in the laboratory values.

Discussion

Our study is not able to demonstrate a significant effect of probiotic therapy with EcN on symptoms of IBS in general. Efficacy of EcN was superior to that of placebo (at best 20% point difference), but effects are limited and have reached the level of significance only after weeks 10 and 11 of the 12-week study period (Fig. 2). The lack of significance may be a sample size problem. Indeed, recent placebo-controlled IBS clinical trials demonstrate a similar therapeutic gain of approximately 10–20% in positive studies [17]. Many symptoms showed improvement in our study. Those effects occurred in the EcN group as well as under placebo. This, again, points to the efficacy of placebo, making it difficult to demonstrate superior effects of a specific therapy.

Study results of probiotic treatment of IBS show wide variability. Though pooled data of a metaanalysis [3] were in favor of probiotic efficacy, different probiotic strains had contradictory results. A thorough systematic review [18] concluded that only the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 shows efficacy. Apparently, not all probiotics are the same, and not all probiotics are likely to be effective. Moreover, it could also be the case that specific probiotics are only active in specific types of IBS.

Looking into more details of the present study, many individual symptoms showed impressive amelioration throughout the study period. However, effects occurred not only in the EcN group but also, somewhat less, under placebo. This points to the efficacy of any IBS treatment known from the international literature, also with placebo, making it difficult to demonstrate superior effects of a specific therapy.

Most likely, IBS is not a single entity but rather a collection of as yet not better definable diseases [19]. Thus, it seems plausible that not a single effective treatment exists for all patients. Different effects of a given treatment in different patient populations are well known [1]. Therefore, it has been recommended to customize therapies to specific types of gastrointestinal dysfunction [20]. As one such specific entity, postinflammatory bowel dysfunction has recently come into the focus of scientific discussion.

A particular focus of the study was to analyze the therapeutic effects in subgroups of IBS. The group of patients with gastroenteritis or antibiotic treatment prior to the onset of their symptoms showed convincing efficacy. Such subgroup effects were also reported for another probiotic [21].

Development of IBS after infectious intestinal diseases has been reported for several years [22]. A recent metaanalysis describes a pooled risk estimate revealing a sevenfold increase in the odds of developing IBS following infectious gastroenteritis [23]. While postinfectious IBS has been reported to occur in about 10–30% of patients with gastroenteritis, the frequency of these particular patients among all IBS patients is not clear. Changes in neuromotor function occur even with mild and superficial inflammation restricted to the mucosa [24]. Mechanisms of postinflammatory functional diseases have been identified, including continued low-grade inflammation, increased availability of serotonin, altered nerve structure and expression of novel receptors [25]. The common link between all of these effects is thought to be alteration of the enteric microflora. Factors such as antibiotics, psychological and physical stress, and certain dietary components have been found to contribute to intestinal dysbiosis in IBS [26]. In a prospective case–control study, subjects who were given a course of antibiotics were more than three times as likely to report more bowel symptoms 4 months later than controls [27].

Therapeutic effects of probiotics can be explained by many mechanisms: either by direct action upon the enteric microflora (cross talk, quorum sensing) or by indirect immunomodulatory, antiinflammatory and barrier activities (cross talk). Recently, persistent changes in proinflammatory (IL-12) and antiinflammatory (IL-10) cytokines were demonstrated in IBS [28]. The administration of probiotic bacteria led not only to symptomatic improvement but also to normalization of the IL-12/IL-10 ratio. Cell extracts and even cell debris of EcN are able to stimulate IL-10 production of peripheral mononuclear cells [29]. Furthermore, among other effects EcN has shown to affect intestinal motility [30], it has strong immunomodulatory properties, it prevents the invasion of pathogens into the mucosa [31], and it induces the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides (e.g. human β-defensins, cathelicidines) as well as the synthesis of tight-junction proteins in intestinal epithelial cells [32, 33].

In conclusion, EcN could not achieve significant efficacy in unselected patients with IBS. But, this exploratory study aimed to define subgroups of patients with IBS who may benefit from treatment with the probiotic EcN. Indeed, the results are promising for the subgroup of IBS patients with altered enteric flora due to gastroenterocolitis or administration of antibiotics. In order to confirm these early results, appropriate clinical trials are indispensable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all hospital staff members for contributing to the work achieved.

Conflict of interest

Wolfgang Kruis served Ardeypharm GmbH as speaker and advisor. The clinical trial was supported by Ardeypharm GmbH, Germany.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Camilleri M. Management of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(3):652–668. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley EMM, Flourie B. Probiotics and irritable bowel syndrome: a rationale for their use and an assessment of the evidence to date. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(3):166–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarland LV, Dublin S. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(17):2650–2661. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuller R. Probiotics in man and animals. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;66(5):365–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb05105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FAO, WHO. Health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria. Report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on evaluation of health and nutritional properties of probiotics in food including powder milk with live lactic acid bacteria. Cordoba, Argentina, 1–4 October 2001. http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/fs_management/en/probiotics.pdf

- 6.Grozdanov L, Raasch C, Schulze J, et al. Analysis of the genome structure of the nonpathogenic probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(16):5432–5441. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5432-5441.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grozdanov L, Zähringer U, Blum-Oehler G, et al. A single nucleotide exchange in the wzy gene is responsible for the semirough O6 lipopolysaccharide phenotype and serum sensitivity of Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(21):5912–5925. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.21.5912-5925.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnenborn U, Schulze J. The non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917—features of a versatile probiotic. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2009;21(3–4):122–58. doi: 10.3109/08910600903444267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Möllenbrink M, Bruckschen E. Behandlung der chronischen Obstipation mit physiologischen Escherichia-coli-Bakterien. Ergebnisse einer klinischen Studie zur Wirksamkeit und Verträglichkeit der mikrobiologischen Therapie mit dem E.-coli-Stamm Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor) [Treatment of chronic constipation with physiologic Escherichia coli bacteria. Results of a clinical study of the effectiveness and tolerance of microbiological therapy with the E. coli Nissle 1917 strain (Mutaflor)] Med Klin. 1994;89(11):587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henker J, Laass M, Blokhin BM, et al. The probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 (EcN) stops acute diarrhoea in infants and toddlers. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166(4):311–318. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0419-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henker J, Laass MW, Blokhin BM, et al. Probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 versus placebo for treating diarrhea of greater than 4 days duration in infants and toddlers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(6):494–499. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318169034c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J, et al. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut. 2004;53(11):1617–1623. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl. II):43–47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruis W, Thieme C, Weinzierl M, et al. A diagnostic score for the irritable bowel syndrome. Its value in the exclusion of organic disease. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinsbekk A, Biolchini J, Heger M, Rezzani C, Tsamis N, van Haselen R, et al. Data collection in homeopathic practice: a proposal for an international standard. European Committee for Homeopathy. Trondheim, Norway: Data Collection Group (DCG); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong E, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, et al. Development of a questionnaire to measure quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Surg. 1998;164(Suppl. 583):50–56. doi: 10.1080/11024159850191247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang L. The trials and tribulations of drug development for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(Suppl 1):130–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner DM, Moeller MJ, Chey WD, et al. The utility of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(4):1033–1049. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ. A unifying hypothesis for the functional gastrointestinal disorders: really multiple diseases or one irritable gut? Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2006;6(2):72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mertz HR. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2136–2146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1581–1590. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(6):1662–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00324-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halvorson HA, Schlett CD, Riddle MS. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome—a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1894–1899. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins SM. The immunomodulation of enteric neuromuscular function: implications for motility and inflammatory disorders. Gastroenterology. 1996;111(6):1683–1699. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(96)70034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiller RC. Infection, immune function, and functional gut disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):445–455. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawrelak JA, Myers SP. The causes of intestinal dysbiosis: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9(2):180–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxwell PR, Rink E, Kumar D, et al. Antibiotics increase functional abdominal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(1):104–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, et al. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(3):541–551. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helwig U, Lammers KM, Rizzello F, et al. Lactobacilli, bifidobacteria and E. coli Nissle induce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(37):5978–5986. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i37.5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bär F, von Koschitzky H, Roblick U, et al. Cell-free supernatants of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 modulate human colonic motility: evidence from an in vitro organ bath study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:559–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altenhoefer A, Oswald S, Sonnenborn U, et al. The probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 interferes with invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells by different enteroinvasive bacterial pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40(3):223–229. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Wehkamp K, et al. NF-k-B- and AP-1-mediated induction of human beta defensin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917: a novel effect of a probiotic bacterium. Infect Immun. 2004;72(10):5750–5758. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5750-5758.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cichon C, Enders C, Sonnenborn U, et al. DNA-microarray-based comparison of cellular responses in polarized T84 epithelial cells triggered by probiotics: E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) and Lactobacillus acidophilus PZ1041. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):A-578–A-579. [Google Scholar]