Abstract

Recent progress in molecular imaging has provided new important knowledge for further understanding the time course of early pathological disease processes in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Positron emission tomography (PET) amyloid beta (Aβ) tracers such as Pittsburgh Compound B detect increasing deposition of fibrillar Aβ in the brain at the prodromal stages of AD, while the levels of fibrillar Aβ appear more stable at high levels in clinical AD. There is a need for PET ligands to visualize smaller forms of Aβ, oligomeric forms, in the brain and to understand how they interact with synaptic activity and neurodegeneration. The inflammatory markers presently under development might provide further insight into the disease mechanism as well as imaging tracers for tau. Biomarkers measuring functional changes in the brain such as regional cerebral glucose metabolism and neurotransmitter activity seem to strongly correlate with clinical symptoms of cognitive decline. Molecular imaging biomarkers will have a clinical implication in AD not only for early detection of AD but for selecting patients for certain drug therapies and to test disease-modifying drugs. PET fibrillar Aβ imaging together with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers are promising as biomarkers for early recognition of subjects at risk for AD, for identifying patients for certain therapy and for quantifying anti-amyloid effects. Functional biomarkers such as regional cerebral glucose metabolism together with measurement of the brain volumes provide valuable information about disease progression and outcome of drug treatment.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by a slow continued deterioration of cognitive processes. The first symptoms of episodic memory disturbances might be quite subtle. When the patient is assessed for memory problems the disease has most probably been ongoing in the brain for several years and has most probably induced nonrepairable disturbances of important functional neuronal networks and loops of the brain. It is a challenge to test whether some of these changes could be reversed or slowed down with early drug treatment.

The recent progress in AD research has provided new knowledge for further understanding the pathology processes of AD that precede the onset of clinical disease by many years. It is still an open question why some people can cope with AD brain pathology better than others. Do they have greater capacity of neuronal compensation? Is there ongoing neurogenesis in the brain? The resistance toward increased pathological burden especially observed in highly educated subjects might be a sign of increased brain plasticity as well as greater cognitive reserve [1].

Since Dr Alois Alzheimer first described the AD disease, amyloid beta (Aβ) has played a central role in AD pathology. It has not yet been proven that Aβ is the primary causative factor of AD. A puzzling observation from autopsy AD brain studies has been the weak correlation between fibrillar Aβ load in the brain and cognition while the amount of neurofibrillary tangles significantly correlates with the cognitive status and duration of dementia [2-4]. The effects of Aβ in the clinical stages of AD are most probably mediated by the presence of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain [5]. In addition, a sequential cascade of events including oxidative stress reactions, inflammatory processes and neurotransmitter and receptor dysfunction most probably contributes to the impairment of cognitive function [6].

Molecular imaging techniques have rapidly developed during recent years. This development not only allows one to measure brain structural changes in patients (atrophy, volume changes and cortical thickness) by magnetic resonance imaging, but also to visualize and quantify brain pathology (fibrillar Aβ, tau, activated microglia and astrocytosis) as well as functional changes (cerebral glucose metabolism, neurotransmitter and neuroreceptor activity) by positron emission tomography (PET) (Table 1). Molecular imaging thus provides important insight into the ongoing pathological processes in AD in relation to clinical symptoms and disease progression. An important step forward has been in vivo imaging of Aβ pathology in AD patients. Although the histo-pathological confirmation of diagnosis at autopsy is important, it reflects the end stage of a disease that may have been ongoing for decades.

Table 1.

Pathological and functional biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease

| Pathological Alzheimer's disease biomarkers |

| Positron emission tomography |

| Fibrillar amyloid beta (11C-Pittsburgh Compound B, 18F-flutemetamol, 18F-florbetapir, and 18F-florbetaben) |

| Tau (18F-FDDNP) |

| Microglia (11C-PK11195, 11C-DA1106) |

| Astrocytes (11C-D-deprenyl) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (atrophy, hippocampal volume, cortical thickness) Cerebrospinal fluid (amyloid beta 1-42, tau, p-tau) |

| Functional Alzheimer's disease biomarkers |

| Positron emission tomography |

| Cerebral glucose metabolism (18F-FDG) |

| Neurotransmitter activity (for example, 11C-CFT, 11C-PMP) |

| Neuroreceptors (for example, 11C-raclopride, 18F-alanserine, 11C-nicotine) |

| Functional magnetic resonance imaging, spectroscopy |

| Single-photon emission computed tomography (cerebral blood flow) |

The new molecular imaging techniques provide possibilities to develop early diagnostic biomarkers for early detection of AD at preclinical stages, as well as for monitoring effects of drug therapy. Recent research has thus also changed the view on incorporating biomarkers into the standardized clinical diagnosis of AD as suggested by Dubois and colleagues [7,8] and the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for AD [9,10].

Amyloid imaging in Alzheimer's disease patients

Among the first Aβ PET tracers was Pittsburgh Compound B (11C-PIB) when 16 AD patients were initially scanned in Sweden [11]. The high 11C-PIB retention observed in cortical and subcortical brain regions of mild AD patients compared with age-matched healthy subjects has consistently been confirmed with 11C-PIB in several other studies (for a review see [12-14]). Several other Aβ PET tracers have also been tested in AD and control patients [12,15] although so far 11C-PIB is the most explored. 18F-labeled tracers will probably be more suitable for use in the clinic, with their longer half-life. 18F-FDDNP was the first 18F-PET tracer used for visualizing Aβ plaque in AD patients [16], showing lower binding affinity to Aβ plaques than 11C-PIB but also suggested to bind to neurofibrillary tangles [16,17]. The 18F-labeled Aβ PET tracers 18F-flutemetamol, 18F-florbetapir and 18F-florbetaben have shown promising results in AD patients [18-20].

The PET Aβ tracers quantify fibrillar Aβ in the brain by binding in the nanomolar range to the Aβ peptide [21]. The in vivo 11C-PIB retention correlates with 3H-PIB binding as well as levels of Aβ measured in autopsy AD brain tissue [22-25]. 18F-florbetapir PET imaging has also been shown to correlate with the presence of Aβ amyloid at autopsy [26], as well as 18F-flutemetamol PET imaging to amyloid measured in cortical biopsies [27].

A still unknown factor is the relationship between fibrillar Aβ (plaques) and soluble Aβ oligomers. Presently there is no information on how the smaller soluble Aβ oligomers, which are known for triggering synaptic dysfunction [28-30], can be visualized in vivo in man with the presently available Aβ tracers. It is therefore a challenge to try to develop PET tracers that can visualize these smaller forms of Aβ in the brain, although the probably lower content of oligomers in AD brains compared with fibrillar Aβ might be a limiting factor. The soluble Aβ oligomers are important since they probably can induce and interfere with the neurotransmission in the brain [30,31].

Longitudinal PET amyloid studies in Alzheimer's disease patients

There are still few longitudinal studies of Aβ PET imaging in AD patients. These studies are important to under-stand the rate of accumulation of amyloid in the brain and are important for evaluation of intervention in anti-amyloid drugs. A 2-year follow-up study with 11C-PIB in AD patients revealed at group level consistent stable fibrillar Aβ levels in the brain [32]. Two additional 1-year and 2-year follow-up studies confirmed these observations [33,34] as well as a recent 5-year follow-up PET study of the first imaged PIB PET cohort [35]. In the latter study it was evident at the individual level that increased, stable and decreased PIB retention were observed and the disease progression was reflected in significant decline in cerebral regional cerebral glucose metabolism (rCMRglc) and cognition [35]. In a recent 20-month follow-up study, Villemagne and colleagues reported a 5.7% increase in fibrillar Aβ in AD patients [36]. The longitudinal imaging studies mainly support the assumption that the Aβ levels in the AD brain reach a maximal level at the early clinical stage of the disease, although both increase and decline in later stages of the disease cannot be excluded [12,37,38].

Amyloid imaging in mild cognitive impairment patients

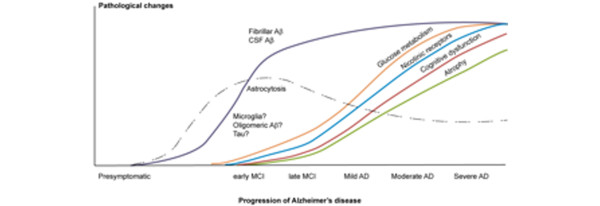

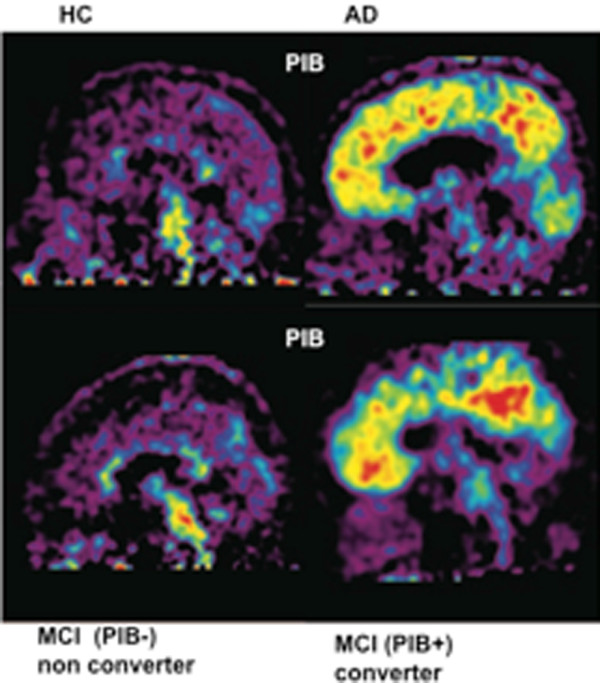

11C-PIB PET studies in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients have revealed a bimodal distribution. Both high (PIB+) and low (PIB-) retention of the PET tracer has been demonstrated [39,40]. PIB + MCI patients seem to have a greater risk to convert to AD after clinical follow-up compared with PIB- MCI patients [39,41,42]. Figure 1 illustrates high 11C-PIB retention in a MCI patient (PIB+) who later converted to AD in comparison with a non-converting MCI patient (PIB-). PIB+ MCI patients show comparably high11C-PIB retention to AD patients (Figure 1). We recently observed a significant increase in brain 11C-PIB retention in early MCI patients when re-scanned after 3 years [35]. The MCI patients also showed a decrease in rCMRglc while they remained stable in cognitive function at follow-up [35]. Jack and colleagues [34] and Villemagne and colleagues [36] have also reported annual changes in 11C-PIB retention. These findings support a continuous increase in Aβ load in the early stage of prodromal AD [35] (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Pittsburgh Compound B retention in the brain. Pittsburgh Compound B (11C-PIB) retention in the brain of a healthy control (HC), an Alzheimer patient (AD), patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who later at clinical follow-up converted to AD, and patients with MCI who did not later convert to AD. PIB+, high Pittsburgh Compound B retention; PIB-, low Pittsburgh Compound B retention. Red, high 11C-PIB retention; yellow, medium 11C-PIB retention; blue, low 11C-PIB retention.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of changes in pathological and functional imaging markers during progression of Alzheimer's disease. Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer's disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Amyloid imaging in older subjects without cognitive impairment

High Aβ has been measured in older cognitive normal controls (for a review see [43]). The reported percentage of positive Aβ PET scans varies from 10 to 50% between different cohorts of studied older people without cognitive impairment [44,45]. A possible explanation for variation in percentage of Aβ PET-positive cognitive normal subjects could be age but also genetic background (APOE genotype). Aβ alone most probably does not account for the decline in memory in older people. Further longitudinal studies are needed to investigate to what extent these Aβ-positive older people with normal cognition will later convert to AD [46]. In a recent longitudinal study of 159 older subjects with normal cognition and PIB+, PET showed a greater risk for developing symptomatic AD within 2 to 5 years compared with PIB- subjects [47].

Relationship between brain amyloid and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers

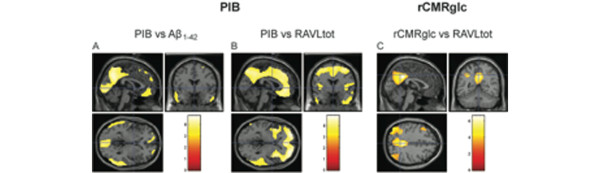

There is a strong inverse correlation between accumulations of fibrillar Aβ in the brain as measured by 11C-PIB and levels of Aβ1-42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [39,48-55]. An inverse correlation between 11C-PIB retention and CSF Aβ1-42 has been demonstrated in prodromal AD (MCI) earlier than changes in functional parameters (cerebral glucose metabolism, cognition) [54] (Figure 2). Figure 3 illustrates the inverse relationship between Aβ in the brain and the CSF as analyzed with statistical parametric mapping cluster analysis. A positive relationship has also been observed between 11C-PIB retention and levels of CSF tau and p-tau [39,50,51,54]. Which of the biomarkers are most sensitive to detect the earliest pathological signs of the disease is still unclear.

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography measurements, cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta 1-42 and episodic memory scores. Statistical parametric mapping analysis showing clusters with significant covariance between positron emission tomography measurements versus levels of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta 1-42 (Aβ1-42) and episodic memory scores measured by means of Rey Auditory Verbal Learning (RAVLtot) tests, using data from Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment patients, at threshold P < 0.001, uncorrected for multiple comparisons. (a) Areas with significant covariance between Pittsburgh Compound B (11C-PIB) retention and concentrations of Aβ1-42 in CSF. (b) Clusters with significant covariance between 11C-PIB retention and scores in RAVLtot tests. (c) Significant clusters of covariance between regional cerebral glucose metabolism (rCMRglc) and scores in RAVLtot tests. Data from [54].

Some data suggest that 11C-PIB PET imaging detects amyloid pathology prior to CSF biomarkers [39,49,54]. Soluble Aβ oligomers might be the most pathogenic in AD. An interesting observation is therefore that AD patients with the APP arctic mutation show no fibrillar Aβ in the brain (PIB-negative) but a reduction of Aβ42 in CSF as well as a reduction in cerebral glucose metabolisms by PET [56].

Imaging of inflammatory processes in Alzheimer's disease brain

Inflammatory processes have been suggested to cause the pathological processes of AD [57,58]. Amyloid has been observed to mobilize and activate microglia [59]. Activated microglia are found in autopsy brain tissue at sites of aggregated Aβ deposition of AD patients. The peripheral benzodiazepine receptor PET tracer 11C-(R)-PK11195 has been used for measuring the transition of microglia from a resting state to an activated state in the brain. An increase in 11C-(R)-PK11195 binding was described by Cagnin and colleagues in the temporoparietal, cingulated and entorhinal cortices of AD patients as a sign for strong microglia activation compared with controls [60]. Edison and colleagues demonstrated high cortical 11C-(R)-PK11195 binding with reciprocal negative correlation with cognitive performance in AD patients [61]. In some other studies, a lower level of microglia activation was observed in mild AD and MCI [62,63]. 11C-DAA-1106 is a new peripheral benzodiazepine PET tracer that has shown increased binding in several brain regions including the frontal, parietal, temporal cortices and striatum of AD patients compared with age-matched controls [64].

Activated astrocytes participate in the inflammatory processes occurring around the Aβ plaques. An increased number of astrocytes have been measured in autopsy brain tissue from AD patients, especially those with the Swedish APP mutation [65]. A positive correlation has been observed between 3H-PIB binding and GFAP immunoreactivity in autopsy AD brain tissue [25]. It is assumed that synaptic activity might be coupled to utilization of energy through an interaction between astrocytes and neurons where the astrocytes take up glucose and release lactate to neurons [66].

N-[11C-methyl]-l-deuterodeprenyl (11C-DED) has been shown to irreversibly bind to the enzyme monoaminooxidase B expressed in reactive astrocytes. 11C-DED has therefore been tested as a PET ligand for measurement of activated astrocytes. Increased 11C-DED binding was demonstrated in the brain of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease [67]. We have recently observed by PET an increased 11C-DED binding in the cortical and subcortical brain regions of MCI patients compared with AD patients and controls [68]. These observations suggest that astrocytosis might be a very early event in the time course of pathological processes in AD (Figure 2). Further studies are needed to explore the relationship between Aβ and inflammatory processes in the early stages of AD.

Imaging of functional changes in Alzheimer's disease brain

Brain glucose metabolism

2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (18F-FDG) has been widely used both in research and clinically for measurement of regional changes in rCMRglc in AD [10]. A reduction of rCMRglc is often observed in the parietal, temporal, frontal and posterior cingulate cortices. The decline in rCMRglc is more regional specific compared with the increased 11C-PIB retention in large areas of the AD brain [11,32]. The hypometabolism is often more severe in early-onset AD compared with late-onset AD, while no difference in regional 11C-PIB retention has been observed between early-onset and late-onset AD [69]. 11C-PIB PET seems to detect prodromal AD at an earlier disease stage and better separates between MCI subtypes (amnestic versus nonamnestic) than 18F-FDG [39,58,70]. The decline in rCMRglc follows, in contrast to PIB, the clinical progression of AD and shows a strong correlation with changes in cognition [32,35,58,70]. Figure 3 illustrates the correlation between rCMRglc and episodic memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning) and between 11C-PIB and episodic memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning) as analyzed with statistical parametric mapping analysis. The 18F-FDG uptake shows more brain regional specific clusters compared with 11C-PIB [54].

Neurotransmitter and neuroreceptor imaging

Several neurotransmitters are impaired in AD, especially the cholinergic system but also the dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmitter. Several PET tracers have been developed and tested for measuring the different neurotransmitters, enzymes and various subtypes of receptors in AD patients [10]. PET tracers are available for studying dopaminergic, serotonergic and cholinergic systems [12] (Table 1). The cholinergic neurotransmission has so far been the focus for clinical AD therapy. It is therefore worth mentioning that decreases in nicotinic receptors have been demonstrated by PET in AD patients using 11C-nicotine [71] and 18F-fluoro-A-85380 (α4 nicotinic receptors) [72]. The extent of reduction in 11C-nicotine binding correlated with the reduction in level of attention of the AD patients [71]. Presently there is a great interest to develop selective PET tracers for imaging of the α7 nicotinic receptors in the brain since these receptors interact with Aβ and might therefore be a new target for AD therapy [73].

Imaging biomarkers and drug development

Recent progress in molecular imaging and biomarkers indicates that subtle pathological changes indicative for AD disease might be detected decades prior to clinical diagnosis of AD. Differences in the time course are observed between pathological and functional AD imaging biomarkers (Figure 2). PET imaging allows measurement of pathological processes such as deposition of fibrillar Aβ plaques, levels of activated microglia and astrocytosis. There is a need for further exploration of PET tracers visualizing inflammatory processes that might occur at very early disease states (Figure 2). Similarly, there is a great need for PET tracers visualizing the accumulation of Aβ oligomers in different stages of AD (Figure 2). Preclinical data for the new promising PET ligand THK 523 for in vivo tau imaging have recently been presented [74]. Additional PET studies are needed to predict with more accuracy the time course for changes in neurotransmitter function including the nicotinic receptors. Brain atrophy changes (magnetic resonance imaging) correlate closely with cognitive decline and disease progression but less with amyloid load in the brain [14,20,75].

The rapid development of molecular imaging will be important not only for early diagnostic biomarkers and early detection of AD [7-9,46] but also to select patients for certain drug therapies and to identify disease-modifying therapies and testing in clinical trials (Table 2). PET imaging biomarkers could thereby play an important role in identifying patients with elevated risk of developing AD. In addition, fibrillar Aβ imaging could (together with CSF Aβ42) serve as an inclusion criterion as well as a primary outcome in phase 2 and a secondary outcome in phase 3 drug trials. Measurement of rCMRglc and magnetic resonance imaging atrophy changes are probably most useful for predicting the clinical outcomes of drug therapy.

Table 2.

Clinical implications of molecular imaging in Alzheimer's disease

| To increase the understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms |

| To increase the understanding of time course of disease progression |

| To understand the differences in time course between pathology and functional changes |

| To develop diagnostic markers that can predict rate of progression |

| To enable selection of Alzheimer's disease patients to certain therapy |

| To measure brain changes after short-term and long-term therapeutic intervention that correlate with clinical symptoms |

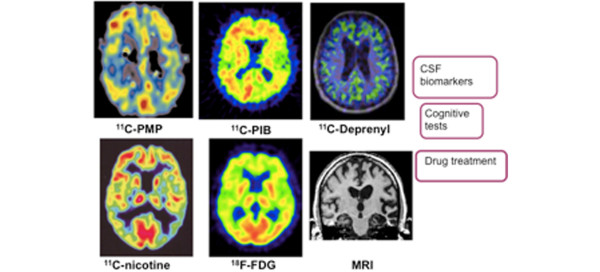

The multi-tracer PET concept offers unique opportunities in drug trials to study pathological as well as functional processes and to relate these processes in the brain to CSF biomarkers and cognitive outcomes (Figure 4). There is now an increased interest to introduce different biomarkers into clinical trials in AD patients [76], which will be important for all drug candidates in the pipeline for AD trials [77]. Long-term treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors in AD patients has shown significant correlation between the degree of inhibition of acetylcholinesterase in the brain, the number of nicotinic receptors, rCMRglc and clinical outcome of treatment measured as attentional test performances [78-82]. To evaluate the effect of new disease-modifying therapeutics, imaging of fibrillar amyloid, activated microglia, astrocytosis, tau in addition to rCMRglc and structural brain changes should be applied to determine whether anti-amyloid strategies may clear the amyloid plaques from the brain but also slow down disease progression. A few PET studies in AD patients have shown reduction of brain Aβ measured by 11C-PIB following anti-amyloid treatment [81,83,84] but the disease-modifying effects still have to be proven.

Figure 4.

Multi-tracer positron emission tomography concept to study pathological and functional processes in the brain. Multi-positron emission tomography tracer concept applied in drug trials combined with atrophy studies (magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers and cognitive testing. 11C-PMP, acetylcholinesterase; 11C-PIB, amyloid; 11C-deprenyl, astrocytosis; 11C-nicotine, nicotinic receptors; 18F-FDG, 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose metabolism. Red, high activity; yellow, medium activity; blue, low activity.

Abbreviations

Aβ: amyloid beta; AD: Alzheimer's disease; 11C-DED: N-[11C-methyl]-L-deuterodeprenyl; 11C-PIB: Pittsburgh Compound B; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; 18F-FDG: 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; PET: positron emission tomography; rCMRglc: regional cerebral glucose metabolism.

Competing interests

AN is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis AB, Jansen-Cilag, Torrey Pines Therapeutics, GSK, Wyeth and Bayer; served on an advisory board for Elan, Pfizer, GSK, Novartis AB, Lundbeck AB, and GE Health Care; served on an advisory board for Elan, Pfizer, GSK, Novartis AB, Lundbeck AB, Merck and GE Health Care; received honorarium for lectures from Novartis AB, Pfizer, Jansen-Cilag, Merck AB, Ely Lilly and Bayer; and received research grants from Novartis AB, Pfizer, GE Health Care and Johnson & Johnson.

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by the Swedish Research Council (Project 05817), the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, Swedish Brain Power, the Swedish Brain Foundation, The Karolinska Institutet Strategic Neuroscience Program, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. MSci Ruiqing Ni is acknowledged for her assistance with Figure 2.

References

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2015–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guannalopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bussière T, Bouras C, Kövari E, Perl DP, Morrison JH, Gold G, Hof PR. Tangles and neuron number but not amyloid load predict cognitive status in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2003;60:1495–1500. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063311.58879.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelsson M, Fukumoto H, Newell KL, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Frosch MP, Albert MS, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC. Early Aβ accumulation and progressive synaptic loss, gliosis, and tangle formation in AD brain. Neurology. 2004;62:925–931. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115115.98960.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR. Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease: a complex but coherent relationship. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1–14. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181919a48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienas JL, Arnold SE. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:378–384. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O'brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Cummings JL, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Delacourte A, Frisoni G, Fox NC, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Hampel H, Jicha GA, Meguro K, O'Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Sarazin M, de Souza LC, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P. Revising the definition of Alzheimer's disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carillo MC, Thies B, Weinstraub S, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtman DM, Pedersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease. Recommendations from the National Instutte on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk W, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausen B, Debnath MS, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Långström B. Imaging of brain amyloid in Alzheimer's brain with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A, Rinne JO, Kadir A, Långström B. The use of PET in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:78–87. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sojkov J, Resnick SM. In vivo human amyloid imaging. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:366–372. doi: 10.2174/156720511795745375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K, Ebmeier K. Clinical amyloid imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:667–670. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A. PET imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:519–527. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00853-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoghi-Jadid K, Small GW, Agdeppa ED, Kepe V, Ercoli LM, Siddarth P, Read S, Satyamurthy N, Petric A, Huang SC, Barrio JR. Localization of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques in the brain of living patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PW, Ye L, Morgenstern JL, Sue L, Beach TG, Judd DJ, Shipley NJ, Libri V, Lockhart A. Interaction of the amyloid tracer FDDNP with hallmark Alzheimer's pathologies. J Neurochem. 2009;109:623–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ackerman U, Browne W, Mulligan R, Pike KL, O'Keefe G, Tochon-Danguy H, Chan G, Berlangieri SU, Jones G, Dickinson-Rowe KL, Kung HP, Zhang W, Kung MP, Skovronsky D, Dyrks T, Holl G, Krause S, Friebe M, Lehman L, Lindemann S, Dinkelborg LM, Masters CL, Villemagne VL. Imaging of amyloid beta in Alzheimer's disease with 18F-BAY94-917, a novel PET tracer: proof of mechanism. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:129–135. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DF, Rosenberg PB, Zhou Y, Kumar A, Raymont V, Ravert HT, Dannals RF, Nandi A, Brasić JR, Ye W, Hilton J, Lyketsos C, Kung HF, Joshi AD, Skovronsky DM, Pontecorvo MJ. In vivo imaging of amyloid deposition in Alzheimer's disease using the radioligand [18F]AV-45 (Florbetapir F18) J Nucl Med. 2010;51:913–920. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe R, Van Laere K, Ivanoiu A, Salmon E, Bastin C, Triau E, Hasselbalch S, Law I, Andersen A, Korner A, Minthon L, Garraux G, Nelissen N, Bormans G, Buckley C, Owenius R, Thurfjell L, Farrar G, Brooks DJ. 18F-flutemetamol amyloid imaging in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a phase 2 trial. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:319–329. doi: 10.1002/ana.22068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, Ikonomovic MD, Lefterov IM, Koldamova RP, Abrahamson EE, Debnath ML, Holt DP, Huang GF, Shao L, DeKosky ST, Price JC, Mathis CA. Binding of the positron emission tomography compound Pittsburgh compound-B reflects the binding of amyloid beta in Alzheimer's disease but not in in transgenic mice brain. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10598–10606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2990-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko S, Bi W, Paljug WR, Debnath ML, Hope CE, Isanski BA, Hamilton RL, DeKosky ST. Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiB-PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2008;131:1630–1645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen V, Alafuzoff I, Aalto S, Suotunen T, Savolainen S, Någren K, Tapiola T, Pirttilä T, Rinne J, Jääskeläinen JE, Soininen H, Rinne JO. Assessment of beta-amyloid in a frontal cortical brain biopsy specimen and by positron emission tomography with carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1304–1309. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.noc80013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedberg MM, Hall H, Hellström-Lindahl E, Estrada S, Guan Z, Nordberg A, Långström B. [(11)C]-PIB binding and levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in postmortem brain tissue from Alzheimer patients. Neurochem Int. 2009;54:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir A, Marutle A, Gonzalez D, Schöll M, Almkvist O, Mousavi M, Mustafiz T, Darreh-Shori T, Nennesmo I, Nordberg A. Positron emission tomography imaging and clinical progression in relation to molecular pathology in the first Pittsburgh Compound B positron emission tomography patient with Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2011;134:301–317. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM, Schneider JA, Bedell BJ, Beach TG, Bilker WB, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Hefti F, Carpenter AP, Flitter ML, Krautkramer MJ, Kung HF, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Reiman EP, Zehntner SP, Skovronsky DM. AV45-A07 Study Group. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA. 2011;305:275–283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk DA, Grachev ID, Buckley C, Kazi H, Grady S, Trojankowksi JQ, Hamilton RH, Sherwin P, McLain R, Arnold SE. Association between in vivo 18-labelled flutemetamol amyloid positron emission tomography imaging and in vivo cerebral histopathology. Artch Neurol. 2011;68:1398–1403. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, Lambert MP, Velasco PT, Bigio EH, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer's-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10191–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, Viola KL, Klein WL. Aβ oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao F, Wicklund L, Lacor P, Klein WL, Nordberg A, Marutle A. Different β-amyloid oligomer assemblies in Alzheimer brains correlate with age of disease onset and impaired cholinergic activity. Neurobiol Aging. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Engler H, Forsberg A, Almkvist O, Blomqvist G, Larsson E, Savitcheva I, Wall A, Ringheim A, Långström B, Nordberg A. Two-year follow-up of amyloid deposition in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2006;129:2856–2866. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinin NN, Alto S, Koikkalainen J, Lötjönen J, Karrasch M, Kemppainen N, Vitanen M, Någren K, Helin S, Scheinin M, Rinne JO. Follow-up of [11C] PIB uptake and brain volume in patients with Alzheimer disease and controls. Neurology. 2009;73:1186–1192. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, Shiung MM, Gunter JL, Boeve BF, Kemp BJ, Weiner M, Petersen RC. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: implication for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2009;132:1355–1365. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir A, Almkvist O, Forsberg A, Wall A, Engler H, Långström B, Nordberg A. Dynamic changes in PET amyloid and FDG imaging at different stages of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:198.e1–198.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Chételat G, Ellis KA, Mulligan RS, Bourgeat P, Ackermann U, Jones G, Szoeke C, Salvado O, Martins R, O'Keefe G, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Ames D, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Longitudinal assessment of Aβ and cognition in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:181–192. doi: 10.1002/ana.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A. Amyloid imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:398–402. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3281a47744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Trojanowski JQ. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer's pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg A, Engler H, Almkvist O, Blomquist G, Hagman G, Wall A, Ringheim A, Långström B, Nordberg A. PET imaging of amyloid deposition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1456–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen NM, Aalto S, Wilson IA, Någren K, Helin S, Brück A, Oikonen V, Kailajärvi M, Scheinin M, Viitanen M, Parkkola R, Rinne JO. PET amyloid ligand [11C-PIB] uptake is increased in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68:1603–1606. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260969.94695.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, Archer HA, Turkheimer FE, Nagren K, Bullock R, Walker Z, Kennedy A, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Rinne JO, Brooks DJ. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years. An 11C-PIB PET study. Neurology. 2009;73:754–760. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b23564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk DA, Price JC, Saxton JA, Snitz BE, James JA, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Cohen AD, Weissfeld LA, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, DeKoskym ST. Amyloid imaging in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:557–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Sojkova J. Amyloid imaging and memory change for prediction of cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3:3. doi: 10.1186/alzrt62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A, Rinne J, Drzezga A, Brooks DJ, Vandenberghe R, Perani D, Almkvist O, Scheinin N, Grimmer T, Okello A, Van Laere K, Hinz R, Carter SF, Kalbe E, Herholz K. PET amyloid imaging and cognition in patients with Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and healthy controls: a European multicenter study [abstract] Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(Suppl 1):P2. [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Bandy D, Chen K, Foster NL, Landau SM, Mathis CA, Price JC, Reiman EM, Skovronsky D, Koeppe RA. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative positron emission tomography core. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Becket LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phleps CH. Towards defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, LaRossa GN, Spinner ML, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, de Kosky ST, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen J, Pirttilä T, Kemppainen N, Aalto S, Herukka SK, Jauhianen AM, Hänninen T, Hallikainen M, Någren K, Rinne JO, Soininen H. PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake and cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid in mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26:378–383. doi: 10.1159/000163927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Price JC, Mathies CA. Relationship between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2009;73:1193–1199. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR Aldea P, Roe CM, Mach RH, Marcus D, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau181 increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:371–380. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolboom N, van der Flier WM, Yaqub M, Boellaard R, Verwey NA, Blankenstein MA, Windhorst AD, Scheltens P, Lammertsma AA, van Berckel BNM. Relationship of cerebrospinal fluid markers to 11C-PiB and 18F-FDDNP binding. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1464–1470. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.064360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer T, Riemenschneider M, Förstl H, Henriksen G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Shiga T, Wester HJ, Kurz A, Drzezga A. Beta amyloid in Alzheimer's disease: increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg A, Almkvist O, Engler H, Wall A, Långström B, Nordberg A. High PIB retention in Alzheimer's disease is an early event with complex relationship with CSF biomarkers and functional parameters. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:56–66. doi: 10.2174/156720510790274446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degerman Gunnarsson M, Lindau M, Wall A, Blennow K, Darreh-Shori T, Basu S, Nordberg A, Lannfelt L, Basun H, Kilander L. Pittsburgh Compound B and Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in CSF, plasma and urine: an explorative study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:204–212. doi: 10.1159/000281832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöll M, Almqvist O, Graff C, Nordberg A. Amyloid imaging in members of a family harbouring the Arctic mutation. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(Suppl 1):303. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Cunningham C, Zotova E, Woolford J, Dean C, Kerr S, Culliford D, Perry VH. Systemic inflammation and disease progression in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:768–774. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b6bb95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotova E, Nicoll JAR, Kalaria R, Holmes C, Boche D. Inflammation in Alzheimer's disease: relevance to pathogenesis and therapy. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010;2:1–9. doi: 10.1186/alzrt24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, Gunn RN, Myers R, Turkheimer FE, Jones T, Banati RB. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet. 2001;358:461–467. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison P, Archer HA, Gerhard A, Hinz R, Pavese N, Turkheimer FE, Hammers A, Tai YF, Fox N, Kennedy A, Rossor M, Brooks DJ. Microglia, amyloid, and cognition in Alzheimer's disease: an [11C](R)PK11195-PET and [11C]PIB-PET study. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello A, Edison P, Archer HA, Turkheimer FE, Kennedy J, Bullock R, Walker Z, Kennedy A, Fox N, Rossor M, Brooks D. Microglia activation and amyloid deposition in mild cognitive impairment: a PET study. Neurology. 2009;72:56–62. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338622.27876.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley CA, Lopresti BJ, Venneti S, Price J, Klunk WE, DeKosky St, Mathis CA. Carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B and carbon 11-labeled (R)-PK11195 positron imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:60–67. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuno F, Ota M, Kosaka J, Ito H, Higuchi M, Doronbekov TK, Nozaki S, Fujimura Y, Koeda M, Asada T, Suhara T. Increased binding of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in Alzheimer's disease measured by positron emission tomography with [11C]DAA1106. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WF, Guan ZZ, Bogdanovic N, Nordberg A. High selective expression of alpha 7 nicotinic receptors on astrocytes in the brains of patients with sporadic Alzheimer's disease and patients carrying Swedish APP 670/671 mutation: a possible association with neuritic plaques. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S, Munch G, Steele M. Activated astrocytes: a therapeutic target in Alzheimer's disease? Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1585–1594. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler H, Lundberg PO, Ekbom K, Nennesmo I, Nilsson A, Bergström M, Tsukada H, Hartvig P, Långström B. Multi-tracer study with positron emission tomography in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SF, Schöll M, Almkvist O, Wall A, Engler H, Långström B, Nordberg A. Evidence for astrocytosis in prodromal Alzheimer's disease provided by 11C-deuterium-L-deprenyl - a multi-tracer PET paradigm combining 11C-PIB and 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2011. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, Alkalay A, Racine CA, O'Neil JP, Janabi M, Baker SL, Agarwal N, Bobasera SJ, Mormino EC, Weiner MW, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Mimller BL, Jagust WJ. Increased metabolic vulnerability in early-onset Alzheimer's disease is not related to amyloid burden. Brain. 2010;133:512–528. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe VJ, Kemp BJ, Jack CR Jr, Senjem M, Weigand S, Shiung M, Smith G, Knopman D, Boeve B, Mullan B, Petersen R. Comparison of 18F-FDG and PIB PET in cognitive impairment. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:878–886. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir A, Almkvist O, Wall A, Långström B, Nordberg A. PET imaging of cortical 11C-nicotine binding correlates with the cognitive function of attention in Alzheimer's disease. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri O, Kendziorra K, Wolf H, Gertz HJ, Brust P. Acetylcholine receptors in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35(Suppl 1):S30–S45. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri RH, Dineley TK. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors interact with beta amyloid: molecular, cellular and physiological consequences. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:27–39. doi: 10.2174/156720510790274464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Okamura N, Furumoto S, Mulligan RS, Connor AR, McLean CA, Cao D, Rigopoulos A, Cartwright GA, O'Keefe G, Gong S, Adlard PA, Barnham KJ, Rowe CC, Masters CL, Kudo Y, Cappai R, Yanai K, Villemagne VL. 18F-THK 523-a novel in vivo tau imaging ligand for Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2011;134:1089–1100. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova LG, Hwang KS, Andrawis JP, Green AE, Babakchanina S, Morra JH, Cummings JL, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jack CR Jr, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Jagust WJ, Koeppe RA, Mathis CA, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. 3D PIB and CSF biomarkers association with hippocampal atrophy in ADNI subjects. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1284–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. Biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease drug development. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;75:e13–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangialasche F, Solomon A, WInblad B, Mecocci P, Kivipelto M. Alzheimer's disease: clinical trials and development. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:702–716. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir A, Darreh-Shori T, Almkvist O, Wall A, Grut M, Strandberg B, Ringheim A, Eriksson B, Blomquist G, Långström B, Nordberg A. PET imaging of the in vivo acetylcholinesterase activity and nicotine binding in galantaminetreated patients with AD. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;28:1201–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir A, Darreh-Shori T, Almkvist O, Wall A, Långström B, Nordberg A. Changes in brain (11C)-nicotine binding sites in patients with mild Alzheimer's disease following rivastigmine treatment as assessed by PET. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:1005–1014. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0725-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darreh-Shori T, Kadir A, Almkvist O, Grut M, Wall A, Blomquist G, Eriksson B, Långström B, Nordberg A. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase in CSF versus brain assessed by 11C-PMP PET in AD patients treated with galantamine. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:168–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadir A, Andreasen N, Almkvist O, Wall A, Forsberg A, Engler H, Hagman G, Lärksäter M, Winblad B, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Långström B, Nordberg A. Effect of phenserine on brain functional activity and amyloid in AD. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:621–631. doi: 10.1002/ana.21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Kadir A, Forsberg A, Porras O, Nordberg A. Long-term effects of galantamine treatment on functional activities as measured by PET in ALzheiner's disease patients. J Alzheimer Dis. 2011;24:109–123. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne JO, Brooks DJ, Rossor MN, Fox NC, Bullock R, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Blennow K, Barakos J, Okello AA, Rodriguez Martinez de Liano S, Liu E, Koller M, Gregg KM, Schenk D, Black R, Grundman M. 11C-PIB PET assessment of change in fibrillar amyoid-beta load in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with bapineuzumab: a phase 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled ascending-dose study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:363–372. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowitzki S, Deptula D, Thurfjell L, Barkhof F, Bohrmann B, Brooks DJ, Klunk WE, Ashford E, Yoo K, Xu ZX, Loetscher H, Santarelli L. Mechanism of amyloid removal in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with gantenerumab. Arch Neurol. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]