Abstract

Introduction

In the present study, we analysed in detail nuclear autoantibodies and their associations in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients included in the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma Registry.

Methods

Sera of 863 patients were analysed according to a standardised protocol including immunofluorescence, immunoprecipitation, line immunoassay and immunodiffusion.

Results

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were detected in 94.2% of patients. In 81.6%, at least one of the autoantibodies highly associated with SSc or with overlap syndromes with scleroderma features was detected, that is, anti-centromere (35.9%) or anti-topoisomerase I (30.1%), followed in markedly lower frequency by antibodies to PM-Scl (4.9%), U1-ribonucleoprotein (U1-RNP) (4.8%), RNA polymerases (RNAPs) (3.8%), fibrillarin (1.4%), Ku (1.2%), aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases (0.5%), To (0.2%) and U11-RNP (0.1%). We found that the simultaneous presence of SSc-associated autoantibodies was rare (1.6%). Furthermore, additional autoantibodies were detected in 55.4% of the patients with SSc, of which anti-Ro/anti-La, anti-mitochondrial and anti-p25/p23 antibodies were most frequent. The coexistence of SSc-associated and other autoantibodies was common (43% of patients). SSc-associated autoantibodies disclosed characteristic associations with clinical features of patients, some of which were previously not acknowledged.

Conclusions

This study shows that five autoantigens (that is, centromere, topoisomerase I, PM-Scl, U1-RNP and RNAP) detected more than 95% of the known SSc-associated antibody responses in ANA-positive SSc patients and characterise around 79% of all SSc patients in a central European cohort. These data confirm and extend previous data underlining the central role of the determination of ANAs in defining the diagnosis, subset allocation and prognosis of SSc patients.

Keywords: systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, autoantibodies, antinuclear antibodies

Introduction

Autoantibodies targeting characteristic nuclear antigens are one of the hallmarks of systemic sclerosis (SSc) [1-3]. The occurrence of different antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) is associated with distinct disease subtypes and with differences in disease severity, including extent of skin involvement, internal organ manifestation and prognosis. Although the current SSc criteria of the American College of Rheumatology [4] do not include the presence of ANAs, The detection of scleroderma-associated antibodies may be a valuable tool in the diagnosis of patients with very early SSc or only subtle symptoms [5,6]. For instance, in a recent study of patients with Raynaud's phenomenon, the presence of ANAs (adjusted HR = 5.67) and SSc-associated antibodies (HR = 4.7) was the strongest independent predictor of definite SSc [6]. Some of the autoantibodies in SSc are regarded as disease-specific and can be correlated with genetic, demographic, diagnostic, clinical and prognostic aspects of the disease [1,3]. Therefore, autoantibodies are pivotal tools in the diagnosis of SSc by helping clinicians make decisions whether to perform further, more detailed and efficient diagnostic procedures, as well as decisions addressing disease management.

For frequently occurring antibodies such as anti-centromere (ACA) and anti-topoisomerase I (ATA), reliable detection systems based on ELISA or other binding tests have been developed. Other antibodies (that is, to fibrillarin, RNA polymerases (RNAPs) and so on) are not identified by common test procedures, but rather by laboratories able to perform sophisticated procedures to confirm the results on the basis of more than one independent method. Even for the most common autoantibodies, the choice of the detection method used is critical to the sensitivity and specificity of the results and hence their diagnostic value [7].

Researchers in numerous studies have examined the presence of antibodies to single predefined antigens in SSc and their clinical associations, whereas many of the investigators who have comprehensively examined large SSc patient cohorts have often restricted their autoantibody analyses to the most common SSc antibodies, ACA and ATA [8-12], or analysed only a few additional antibodies [13-17]. The aim of this study was therefore to characterise all known non-organ-specific, SSc-associated autoantibodies, as well as other, potentially new nuclear autoantibodies by using a standardised protocol in the large SSc patient cohort included in the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma Registry, and to correlate these findings with the clinical characteristics of these patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

Serum samples from 863 consecutive patients included in the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma Registry between 2004 and 2007 from 23 different clinical centres were analysed. Patient data are gathered and registered using a consensual registration form and reference documents with item definitions and recommendations for organ-specific diagnostic procedures as previously described [18,19]. Of the patients included, 82.9% were female, their mean age ± SD was 58.0 ± 13.4 years (median = 60 years, range 12 to 93). The patients' age at disease onset ranged from 3 to 87 years (median = 49 years, mean = 47.7 ± 14.2).

The registry defines five subsets, that is, limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous SSc [20], overlap syndrome [21,22], systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma [23,24] and undifferentiated connective tissue disease with features of scleroderma [25,26], as recently described [18]. The latter subset corresponds largely to the subgroup 'early SSc' as described by LeRoy and Medsger [5] but may also include patients who will never develop definite SSc. The study, including the patients' informed consent regarding data storage, was approved by the lead Ethics committee of the Cologne University Hospital and by the respective ethics committees of the contributing centres.

Autoantibody analysis

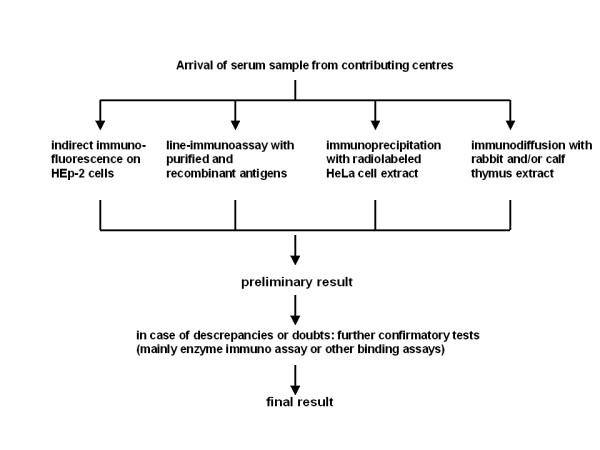

To detect SSc-associated autoantibodies in a comprehensive way, we used the search strategy commonly performed in diagnostic procedures for connective tissue diseases based on a HEp-2 cell immunofluorescence assay followed by tests using cellular extracts and/or recombinant antigens. This strategy is focused on circulating antibodies against non-organ-specific cellular autoantigens. Cell- or tissue-specific autoantibodies, which have also been described in scleroderma patients [3], were not included in the analytical protocol. At least one serum draw from each patient (N = 863) was analysed for circulating autoantibodies by a predefined protocol (Figure 1) with at least four assay systems performed in a single laboratory by a single group of technologists.

Figure 1.

Protocol for serological analysis of systemic sclerosis patient sera.

Indirect immunofluorescence using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G was performed as a screening method for the detection of ANAs on HEp-2 cells (HEp-20-10; Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) seeded onto a microscope slide [27]. Titres of at least 1:80 dilution were regarded as positive. Different nuclear and cytoplasmic fluorescence patterns were documented.

A line immunoassay (EUROLINE ANA Profile 3; Euroimmun) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. This assay is able to detect, by binding to recombinant or purified antigens, the following autoantibodies: U1-ribonucleoprotein (U1-RNP), Sm, Ro60, Ro52, La (SS-B), Scl-70, PM-Scl, centromere protein B (CENP-B), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), nucleosomes, histones, ribosomal P proteins and the mitochondrial M2 antigen.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) of radiolabelled HeLa cell extract was performed as described [28,29] with slight modifications. In brief, HeLa S3 cells in suspension culture in methionine-deficient RPMI medium with 10% dialyzed foetal bovine serum were incubated with 35S methionine (to a final activity of 0.3 MBq/ml) overnight. They were (1) washed in Tris-buffered saline and (2) lysed by resuspension in IP buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, with 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Igepal (Sigma, Munich, Germany) and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and sonication on ice. IP was performed by incubation of patient sera (10 μl) with protein A Sepharose beads (2 mg in 500 μl; Sigma) for two hours, three short washing steps, end-over-end rotation with the radiolabelled cell extract overnight, five washing steps, separation of the precipitates on 5% to 20% gradient SDS-PAGE gels and subsequent autoradiography for six to ten days. Bands typical of autoantibodies were identified according to their apparent molecular weight and comigration with bands produced by reference sera with known autoantibody specificity. After we completed this procedure, the autoantibodies to the following antigens were routinely detectable: topoisomerase I (Scl-70), RNAPs (I and/or III), Ku, fibrillarin, To, NOR-90, Pl-7, Pl-12, EJ, OJ, KS, Mi-2, signal recognition particle, ribonucleoprotein (usually U1-RNP), SL, PCNA, ribosomal P proteins and p25/p23, also known as 'anti-chromo' [30,31]. In our hands, the detection of antibodies to Ro, La, PM-Scl, Jo-1, centromere antigens and the mitochondrial M2 antigen was unreliable by this method. Bands of unknown nature were registered and entered into the database of autoantibody results.

Immunodiffusion (ID) was performed in Agarose gels with rabbit and/or calf thymus extract (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR, USA) as described previously [32]. Autoantibodies were identified by the identity of precipitation lines with patient sera compared with monospecific prototype sera with known autoantibody specificity. The use of prototype serum was guided by results of the immunofluorescence pattern on HEp-2 cells. The following autoantibodies were detectable: topoisomerase 1 (Scl-70), PM-Scl, Ku, SL, Jo-1, Pl-7, U1-RNP, Sm and La (SS-B). Precipitation bands that did not merge with any of the prototype sera were registered as unknown autoantibodies and entered into the database of autoantibody results.

In selected sera, confirmatory assays using recombinant or synthetic antigens (see Table 1 Antibody detection criteria) were performed. More than one serum sample was available from 213 patients (from 2 to 25 samples). At least one serum sample per patient was tested with the whole protocol described in Figure 1, whereas in most cases the follow-up sera drawn were at least partially characterised with, for example, the HEp-2 cell test. The criteria for classifying sera as positive for autoantibodies are listed in Table 1 together with additional serological results commonly found and helpful to identify the antibodies.

Table 1.

Methodological criteria for assignment of autoantibodies

| Autoantibody against | Findings classifying patients as antibody-positive | Usual additional findings |

|---|---|---|

| Centromere | Centromeric immunofluorescence pattern on HEp-2 cells (308 of 310 were positive) or a CENP-B band in line assay (309 of 310 positive) | |

| Topoisomerase I | At least two of three findings: Scl-70-positive signal in line assay (258 of 260 positive), a band comigrating with a prototype band in IP (all positive), a line of identity in ID with the Scl-70 prototype serum (244 of 260 positive) | Typical HEp-2 cell immunofluorescence pattern: fine granular karyoplasmic, weakly nucleolar, metaphase chromosome-positive |

| RNA polymerases | Characteristic IP pattern comigrating with the pattern of a prototype serum mainly consisting of four bands: Ia, Ib, IIIa and IIIb [58] | Confirmation by ELISA in 32 of 32 cases with the immunodominant epitope of RNA polymerase III subunit RPC155 according to Kuwana et al. [71], provided by Matritec, Freiburg, Germany. ANA immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells was predominantly fine granular only sometimes (five cases) in addition nucleolar [72]. |

| Fibrillarin | An IP band (approximately 34 kDa) comigrating with a prototype serum band, plus a nucleolar immunofluorescence pattern on HEp-2 cells | Confirmation by investigational ELISA kindly provided by Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany, positive in 11 and borderline in 1 of the 12 cases |

| To | An IP band of approximately 40 kDa plus a nucleolar immunofluorescence pattern on HEp-2 cells; confirmation by immunoblot analysis with recombinant To antigen kindly supplied by Dr M Blüthner, Labor Seelig, Karlsruhe, Germany | |

| PM-Scl | A line of identity in ID with a PM-Scl prototype serum (41 of 42 cases) and/or positive result of ELISA with the synthetic peptide PM-1α [73] (Dr Fooke Laboratorien GmbH, Neuss, Germany) (12 of 13 cases) | Positive reaction in 37 of 41 cases for PM-Scl by line assay. ANA immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells usually was nucleolar plus fine granular karyoplasmic. |

| Ku | Two prominent IP bands at about 70 and 80 kDa comigrating with prototype bands | In 3 of 10 cases, a line identical to a Ku prototype band in ID. ANA immunofluorescence was finely granular, usually at a high titre. |

| U1-RNP | A positive signal for RNP/Sm in line assay, with or without a positive signal for Sm, plus a typical IP pattern consisting of at least antigen A (about 33 kDa), antigen B/B' (about 28/29 kDa) and antigen C (about 22 kDa) | In 37 of 41 cases, a line of identity with a U1-RNP prototype in ID. ANA pattern on HEp-2 cells usually was coarsely speckled. |

| Sm | A positive signal for RNP/Sm as well as for Sm in line assay | In two of four cases, a band identical to a Sm prototype in ID with ribonuclease-digested calf thymus extract. IP and immunofluorescence patterns were similar to those found for anti-U1-RNP. |

| Jo-1 | A positive signal for Jo-1 in line assay plus a band identical to a Jo-1 prototype band in ID | Immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells was inconsistent. |

| Pl-7 | IP band of about 80 kDa comigrating with prototype band plus a band identical to a Pl-7 prototype band in ID | Cytoplasmic immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells |

| OJ | Typical triplet band in IP comigrating with prototype bands | Cytoplasmic immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells |

| U11-RNP [74,75] | An RNP-like IP pattern and coarsely speckled ANA immunofluorescence, without any U1-RNP signals in line assay and ID; U11-RNP specificity detected by C Will and R Lührmann, Marburg, Germany | |

| p25/p23 [76,77] | Doublet IP bands of about 25 and 23 kDa, with the 25 kDa band comigrating with the precipitate of rabbit anti-p25 kindly provided by E Chan, Gainesville, FL, USA | HEp-2 cell immunofluorescence pattern was always centromeric because anti-p25/p23 was exclusively found together with anticentromere. |

| SL | A band identical to the SL prototype band in ID plus an IP band at about 31 kDa comigrating with the precipitate of the SL reference serum | HEp-2 cell immunofluorescence pattern was fine granular, but in this study often was masked because of other coexisting antibodies |

| NOR-90 | Doublet IP bands at about 90 kDa comigrating with the precipitate of a NOR-90 reference serum [78] | The nucleolar immunofluorescence pattern expected on HEp-2 cells was hard to detect in the sera examined in this study, because NOR-90 antibodies in all cases coincided with other autoantibodies visible on HEp-2 cells. |

| Mitochondrial M2 | AMA M2-positive signal by line assay (40 of 41 positive) and/or AMA typical cytoplasmic immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells and/or rat kidney sections (27 of 41 positive) | In IP, a band of around 70 kDa was present in 36 of 41 cases. |

| Sp100 | Multiple nuclear dot pattern on HEp-2 cells [79] plus Sp100 signal in the line assay HUMAN IMTEC-Liver Line Immunoassay (HUMAN Diagnostics GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) | |

| Ro52 | Ro52-positive signal by line assay | |

| Ro60 | Ro60-positive signal by line assay | |

| La | La-positive signal by line assay |

AMA = antimitochondrial antibodies; ANA = antinuclear antibodies; CENP-B = centromere protein B; ID = immunodiffusion; IP = immunoprecipitation; PM-Scl = polymyositis and scleroderma; RNAP = RNA polymerase; RNP = ribonucleoprotein;.

In addition to the autoantibodies defined in Table 1 other circulating autoantibodies detected by at least one of the above-mentioned procedures, either known (for example, anti-histone, anti-dsDNA) or unknown (for example, either unidentified bands in IP or ID or antinuclear or anticytoplasmic antibodies on HEp-2 cells without subsequent identification), were registered. Sera which were negative for ANAs in immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells but exhibited cytoplasmic fluorescence in that assay and/or a positive signal in any of the other assays were grouped together as ANA-negative. Sera without any positive signal, neither defined nor undefined, in all four assay systems described above were listed as autoantibody-negative.

Statistics

The data were analysed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS version 14.0 software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) for tabular and graphic representation. Statistical evaluation was performed using contingency table tests with the help of GraphPad Prism version 3.02 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). We calculated OR and 95% CI data. P-values were calculated using Fisher's exact test. When multiple tests were performed, P-values below 0.005 were recorded without performing strict Bonferroni correction. For most variables, less than 5% of data were missing. Quantitative data (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), age at disease onset and Rodnan skin score), depending on the presence or absence of different autoantibodies, were analysed using the Mann-Whitney rank-sum test.

Results and discussion

Of the 863 SSc patients studied, 513 (59.4%) were classified as having limited disease and 173 (20.1%) we classified as having diffuse cutaneous disease. Another 108 patients (12.5%) had a scleroderma overlap syndrome, 64 (7.4%) had undifferentiated connective tissue disease with scleroderma features and 5 (0.6%) had systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma.

The frequency of autoantibodies detected in these patients is shown in Table 2. Overall, ANAs were detected in 94.2% of patients. This frequency was similar to data previously published [12,14,15,33,34] in which ANA frequencies reported were between 85% and 99%. Among our patients with ANAs, 86.6% (704 of 813) had autoantibodies known to be highly associated with SSc, and among these latter patients, 96.4% (679 of 704) had antibodies that detected five antigens: centromere, topoisomerase I, PM-Scl, U1-RNP and RNAPs.

Table 2.

Prevalence of autoantibodies in 863 scleroderma patients

| Autoantibodies | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Positive for antinuclear antibodies | 813 (94.2) |

| Antibodies highly associated with SSc or scleroderma overlap syndromes | 704 (81.6) |

| Anti-centromere | 310 (35.9) |

| Anti-topoisomerase I | 260 (30.1) |

| Anti-PM-Scl | 42 (4.9) |

| Anti-U1-RNP | 41 (4.8) |

| Anti-RNA polymerase | 33 (3.8) |

| Anti-fibrillarin | 12 (1.4) |

| Anti-To | 2 (0.2) |

| Anti-Ku | 10 (1.2) |

| Anti-Jo-1/-Pl-7/-OJ | 4 (0.5) |

| Anti-U11-RNP | 1 (0.1) |

| Other autoantibodies | |

| Anti-Ro and/or anti-La | 206 (23.9) |

| Anti-Ro52 | 187 (21.7) |

| Anti-Ro60 | 59 (6.8) |

| Anti-La | 16 (1.9) |

| Anti-mitochondrial M2 | 41 (4.8) |

| Anti-p25/p23 | 28 (3.2) |

| Anti-NOR-90 | 6 (0.7) |

| Anti-SL | 9 (1.0) |

| Anti-Sm | 4 (0.5) |

| Anti-Sp100 | 4 (0.5) |

| Other (known or unknown) | 363 (42.1) |

| Negative for all highly SSc-associated antibodies | 159 (18.4) |

| Negative for antinuclear antibodies | 50 (5.8) |

| Autoantibody-negative by all criteria used | 38 (4.4) |

ANA = antinuclear antibodies; SSc = systemic sclerosis.

A coincidence of SSc-associated autoantibodies (Table 3) was rare, being detected in only 1.6% patients (11 of 704). The presence of a SSc-associated antibody without any other autoantibody detectable by the methods used was found at varying frequencies, being highest for anti-PM-Scl (73.8%) and lower for, for example, anti-centromere (33.9%) and anti-fibrillarin (33.3%) (see Table 3). That SSc-associated autoantibodies are largely mutually exclusive is well-known [14,15,35]. Coincidences in individual patients do occur but are rare [33,36,37]. Our study shows that this statement holds true even if all known non-organ-specific, SSc-associated autoantibodies are sought using a rigorous protocol in all patients. On the other hand, additional (mainly not SSc-specific) autoantibodies are common and were detected in about 53% in our patient cohort with SSc-associated antibodies (and in 55.4% of all of our patients). In 14.0% of patients (n = 121), none of the above-mentioned SSc-associated but other (defined or undefined) autoantibodies were found, whereas in 4.4% no autoantibodies at all were detected by the methods used. Defined autoantibodies not regarded as SSc-specific, such as anti-Ro/La, anti-NOR-90 or AMAs rarely occurred without the evidence of SSc-associated autoantibodies (Table 3). Antibodies to p25/p23 were detected exclusively in conjunction with ACA.

Table 3.

Coincidence* of autoantibodies in 863 individual systemic sclerosis patients

| Antibodies | ACA | ATA | Anti-PM-Scl | Anti-U1-RNP | Anti-RNAP | Anti-fibrilla-rin | Anti-To | Anti-Ku | Anti-Jo-1/Pl-7/OJ | Anti-U11-RNP | Anti-Ro52 | Anti-Ro60 | Anti-La | AMA | Anti-p25/p23 | Anti-NOR-90 | Anti-SL | Anti-Sm | Anti-Sp100 | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 92 | 11 | 1 | 31 | 28 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 144 | |

| ATA | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 26 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 77 | ||

| Anti-PM-Scl | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Anti-U1-RNP | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 11 | ||||

| Anti-RNAP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |||||

| Anti-fibrillarin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | ||||||

| Anti-To | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||||||

| Anti-Ku | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||

| Anti-Jo-1/Pl-7/OJ | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| Anti-U11-RNP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Anti-Ro52 | 41 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 97 | |||||||||||

| Anti-Ro60 | 14 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 33 | ||||||||||||

| Anti-La | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | |||||||||||||

| AMA | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 29 | ||||||||||||||

| Anti-p25/p23 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 18 | |||||||||||||||

| Anti-NOR-90 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Anti-SL | 0 | 0 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Anti-Sm | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Anti-Sp100 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Isolateda | 104 | 153 | 31 | 19 | 23 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 79 |

| Totalb | 310 | 260 | 42 | 41 | 33 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 187 | 59 | 16 | 41 | 28 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 363 |

*Number of patients with co-occurrences of autoantibodies. aIsolated: presence without coincidence of any other autoantibody by all detection methods used. bTotal number of individuals with the respective autoantibody; these numbers mostly are smaller than the sum of all co-occurrences plus the 'isolated' individuals listed because of some triple, quadruple and higher-order coincidences. ACA = anti-centromere antibodies; AMA = antimitochondrial antibodies; ATA = anti-topoisomerase I antibodies;; RNAP = RNA polymerase; RNP = ribonucleoprotein.

From 213 patients, more than one serum sample was available (from 2 to 25 samples). In the majority (86.4%) of cases, the results of follow-up testing remained essentially the same and differed in ANA titre by up to only two titre steps. In 11.3% (24 patients), ANA titre changes exceeded two steps (up to eight steps), in two cases ANAs turned negative, in one case the ANA pattern changed from finely granular to nucleolar and in only two cases new, additional typical SSc autoantibodies emerged.

The detection of antibodies in different disease subsets is shown in Table 4. It is obvious that ACA and ATA are not exclusive to either the limited or the diffuse subset. In patients with overlap syndrome, anti-U1-RNP, anti-PM-Scl and anti-synthetase antibodies are characteristic.

Table 4.

Autoantibodies in different disease subsets in 863 individual systemic sclerosis patients

| Limited (N = 513) | Diffuse (N = 173) | Overlap (N = 108) | Undifferentiated (N = 64) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | n (%) | ORa (P-value) | n (%) | OR (P-value) | n (%) | OR (P-value) | n (%) |

| ACA | 253 (49.3) | 5.00 (P < 0.0001) | 12 (6.9) | 16 (14.8) | 28 (43.8) | ||

| ATA | 141 (27.5) | 98 (56.6) | 4.26 (P < 0.0001) | 11 (10.2) | 9 (14.1) | ||

| Anti-RNAP | 14 (2.7) | 14 (8.1) | 3.11 (P = 0.0029) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Anti-U1-RNP | 7 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (28.7) | 30.00 (P < 0.0001) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Anti-PM-Scl | 16 (3.1) | 2 (1.2) | 22 (20.4) | 9.40 (P < 0.0001) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Anti-fibrillarin | 3 (0.6) | 8 (4.6) | 8.32 (P = 0.0005) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Anti-To | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Anti-Jo-1/Pl-7/OJ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.7) | 65.07 (P = 0.0002) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Anti-U11-RNP | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Anti-Ku | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Anti-SL | 5 (1.0) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Anti-Sm | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.8) | 21.54 (P = 0.0069) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Anti-NOR-90 | 5 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| AMA | 28 (5.5) | 4 (2.3) | 4 (3.7) | 5 (7.8) | |||

| Anti-Sp100 | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Anti-Ro52 | 125 (24.4) | 1.50 (P = 0.023) | 20 (11.6) | 27 (25.0) | 15 (23.4) | ||

| Anti-Ro60 | 28 (5.4) | 14 (8.1) | 13 (12.0) | 2.11 (P = 0.0382) | 4 (6.3) | ||

| Anti-La | 9 (1.8) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (4.7) | |||

| Anti-p25/p23 | 24 (4.5) | 4.25 (P = 0.0031) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Other | 209 (40.7) | 74 (42.8) | 44 (40.7) | 34 (53.1) | |||

| ANA-negative | 32 (6.2) | 6 (3.5) | 5 (4.6) | 7 (10.9) | |||

ACA, anti-centromere antibodies; AMA, antimitochondrial antibodies; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; ATA, anti-topoisomerase I antibodies; RNAP, RNA polymerase;. aOR for antibody in that subset compared with all other subsets. Only significant positive associations are documented by OR, and those with P-values < 0.005 are printed in bold.

The correlation of demographic features or signs and symptoms of SSc with the presence or absence of defined autoantibodies was investigated by contingency table analysis. The frequencies of these features and their positive or negative correlations with specific autoantibodies are listed in Table 5. For the purpose of clarity, only those comparisons that led to P-values below 0.05 derived by Fisher's exact test are shown. Significance was calculated without correction of P-values for multiple comparisons, because not all variables used were independent; however, we are aware of the fact that some of the weak associations listed in Table 5 might have arisen by chance due to the high number of comparisons made. Therefore, we focused on those differences calculated that were highly significant (P < 0.005; OR printed in bold in Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlations of clinical features with SSc associated autoantibodies

| ACA (310) |

ATA (260) |

Anti-PM-Scl (42) |

Anti-U1-RNP (41) |

Anti-RNA -P (33) |

Anti-Fibrillarin (12) |

Anti-Ku (10) |

Anti-Ro52 (187) |

Anti-Ro60 (59) |

Anti-La (16) |

AMA (41) |

Anti-p25/23 (28) |

ANA-negative (50) |

no SSc associated ab's (161) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male sex 148 (17.1%) |

17 0.19 (0.11 to 0.32) P < 0.0001 |

64 2.02 (1.4 to 2.91) p = 0.0002 |

6 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 23 0.62 (0.38 to 0.997 p = 0.049 |

12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

41 1.90 (1.261 to 2.863) p = 0,0035 |

| age at disease onset < 50 y 399/781 (51.1%) |

115 0.57 (0.43 to 0.77) p = 0.0003 |

135 1.39 (1.02 to 1.88) p = 0.0431 |

22 |

29 2.92 (1.40 to 6.07) p = 0.0029 |

13 | 8 | 4 | 77 | 31 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 18 | 73 |

| Rodnan skin score > 10 294/750 (39.2%) |

58 0.27 (0.19 to 0.38) P < 0.0001 |

132 3.10 (2.24 to 4.27) P < 0.0001 |

14 | 9 |

18 3.24 (1.44 to 7.31) p = 0.0042 |

7 | 1 | 58 | 23 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 56 |

| Raynaud's phenomenon 819 (94.9%) |

301 2.26 (1.07 to 4.77) p = 0.0349 |

252 | 37 | 41 | 32 | 12 | 10 | 184 3.96 (1.2 to 12.94 p = 0.0133 |

58 | 16 | 41 | 28 | 43 0.29 (0.12 to 0.70) p = 0.0104 |

140 0.23 (0.12 to 0.42) P < 0.0001 |

| Digital ulcers 216/840 (25.7%) |

55 0.50 (0.36 to 0.71) P < 0.0001 |

106 3.18 (2.30 to 4.41) P < 0.0001 |

9 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 48 | 19 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 4 0.26 (0.09 to 0.76) p = 0.0076 |

28 0.60 (0.39 to 0.94) p = 0.024 |

| Pulmonary hypertension 126 (14.6%) |

57 1.58 (1.08 to 2.32) p = 0.0208 |

36 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 0.23 (0.06 to 0.97) p = 0.0232 |

17 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis 287 (33.3%) |

39 0.18 (0.12 to 0.26) P < 0.0001 |

151 4.76 (3.48 to 6.50) P < 0.0001 |

16 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 69 |

30 2.20 (1.29 to 3.75 p = 0.0040 |

9 | 6 0.33 (0.14 to 0.79) p = 0.01 |

4 0.33 (0.11 to 0.95) p = 0.0393 |

11 | 55 |

| Lung restrictive defect 218/833 (26.2%) |

41 0.31 (0.21 to 0.45) P < 0.0001 |

104 2.96 (2.14 to 4.09) P < 0.0001 |

9 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 45 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 34 |

| Esophageal involvement 535 (62.0%) |

198 | 175 1.39 (1.02 to 1.89) p = 0.039 |

14 0.29 (0.152 to 0.56) p = 0.0001 |

29 | 20 | 7 | 6 | 120 | 39 | 13 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 87 0.67 (0.47 to 0.94) p = 0.0243 |

| Proteinuria 90/830 (10.8%) |

23 0.56 (0.34 to 0.92) p = 0.0207 |

34 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 19 |

| Cardiac involvement 114 (13.2%) |

27 0.51 (0.32 to 0.81) p = 0.0033 |

45 1.62 (1.08 to 2.44) p = 0.0216 |

5 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 20 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 22 |

| Musculoskeletal involvement 421/852 (49.4%) |

131 0.64 (0.48 to 0.85) p = 0.0022 |

130 | 20 | 28 2.49 (1.25 to 4.96) p = 0.009 |

17 | 10 5.22 (1.14 to 23.97) p = 0.0202 |

6 | 80 0.71 (0.51 to 0.99) p = 0.0468 |

32 | 12 3.13 (1.002 to 9.79) p = 0.0447 |

17 | 9 | 25 | 79 |

| Synovitis 157/837 (18.8%) |

35 0.43 (0.29 to 0.65) P < 0.0001 |

62 1.71 (1.19 to 2.45) p = 0.0049 |

8 | 13 2.27 (1.14 to 4.53) p = 0.0326 |

8 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 15 | 5 | 2 0.21 (0.05 to 0.89) p = 0.0216 |

2 | 10 | 29 |

| Joint contractures 253/840 (30.1%) |

54 0.36 (0.25 to 0.50) P < 0.0001 |

107 2.26 (1.65 to 3.08) P < 0.0001 |

9 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 49 | 23 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 20 1.93 (1.05 to 3.54) p = 0.0436 |

56 |

| Tendon friction rubs 88/840 (10.5%) |

14 0.30 (0.16 to 0.53) P < 0.0001 |

32 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 21 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 25 1.95 (1.18 to 3.22) p = 0.0122 |

| CK elevation 74/835 (8.9%) |

14 0.37 (0.21 to 0.68) p = 0.0009 |

20 |

19 3.56 (1.67 to 7.57) p = 0.0023 |

5 | 6 2.60 (1.03 to 6.55) p = 0.0485 |

0 | 3 5.32 (1.30 to 21.72) p = 0.038 |

21 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 16 |

| Sicca syndrome 366/858 (42.7%) |

150 1.44 (1.19 to 6.61) p = 0.0119 |

98 | 14 | 18 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 96 1.57 (1.13 to 2.17) p = 0.0075 |

33 1.85 (1.08 to 3.17) p = 0.0275 |

12 4.14 (1.32 to 12.93) p = 0.0102 |

19 |

20 3.50 (1.52 to 8.03) p = 0.0029 |

23 | 66 |

| Mouth involvement 223/829 (26.9%) |

64 0.61 (0.44 to 0.85) p = 0.0034 |

93 2.1 (1.53 to 2.93) P < 0.0001 |

10 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 49 | 18 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 34 |

| ESR > 25 mm/h 199/741 (26.9%) |

58 0.70 (0.49 to 0.99) p = 0.046 |

75 1.55 (1.10 to 2.19) p = 0.015 |

4 0.33 (0.11 to 0.94) p = 0.0325 |

14 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

60 1.76 (1.21 to 2.54) p = 0.0039 |

28 3.39 (1.92 to 5.97) P < 0.0001 |

9 3.62 (1.33 to 9.86) p = 0.0447 |

10 | 5 | 15 | 42 |

ACA, anti-centromere antibodies; AMA, antimitochondrial antibodies; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; ATA, anti-topoisomerase I antibodies; CK, creatine kinase; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RNAP = RNA polymerase; RNP = ribonucleoprotein; SSc, systemic sclerosis. Dichotomous variables are expressed as raw numbers, OR (95% CI) and P values.

Patients with ACA represented 35.9% of all SSc patients and 38.1% of ANA-positive SSc patients. In accordance with previous reports [8,9,12,15,33,36,38,39], these patients were less often male, were older at disease onset and had a more limited extension of cutaneous involvement, as documented by a much lower OR for a Rodnan skin score (RSS) above 10 (Table 5) and by a very significantly lower mean RSS (Table 6). They had less involvement of internal organs (pulmonary fibrosis, cardiac, musculoskeletal and oral involvement), with the exception of pulmonary hypertension. An association of ACA with pulmonary hypertension has been observed in several previous reports [2,12,33,40], but not all of them [13,36,38,39]. Digital ulcers in our patients with ACA were less common compared to American patients [2] and more similar to European [9,12,38] and Japanese patients [34]. Nevertheless, the presence of ACA does not by any means preclude digital ulcers. To date no marker constellation allows the identification of patients prone to this complication [41-43]. ACAs are frequently associated with other antibodies, such as anti-Ro [44-46], anti-mitochondrial (M2) [15,44,47,48] and anti-p25/p23 [31,49,50] antibodies. These associations were confirmed by this study. The reasons for this frequent co-occurrence are unknown. There is no known antigenic relationship between the individual targets of the antibodies. Probably the (unknown) aetiopathogenetic pathways marked by these antibodies have common components, including common genetic predispositions.

Table 6.

Correlations of clinical features with systemic sclerosis-associated autoantibodies

| Quantitative traits | Clinical data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at disease onset | n | Mean ± SD (years) | P* |

| Total | 781 | 47.7 (14.2) | |

| Anti-centromere | 273 | 51.3 (12.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-topoisomerase I | 238 | 46.0 (14.0) | 0.0076 |

| Anti-fibrillarin | 12 | 38.8 (16.0) | 0.0404 |

| Anti-U1-RNP | 39 | 38.2 (15.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-La | 15 | 37.9 (18.1) | 0.0431 |

| Autoantibody-negative | 36 | 52.9 (14.7) | 0.0205 |

| Rodnan skin score | n | Mean score ± SD | P |

| Total | 750 | 10.2 (9.4) | |

| Anti-centromere | 275 | 6.4 (6.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-topoisomerase I | 227 | 14.1 (9.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-RNA polymerase | 27 | 15.7 (11.7) | 0.0091 |

| Anti-fibrillarin | 10 | 21.2 (15.0) | 0.0108 |

| Anti-U1-RNP | 35 | 6.9 (9.2) | 0.0053 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | n | Mean ± SD (mm/hour) | P |

| Total | 741 | 19.46 (16.7) | |

| Anti-topoisomerase I | 227 | 22.95 (19.1) | 0.0002 |

| Anti-PM-Scl | 36 | 12.19 (9.4) | 0.0014 |

| Anti-Ro52 | 167 | 22.05 (18.8) | 0.0374 |

| Anti-Ro60 | 53 | 28.47 (19.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-La | 16 | 28.56 (20.1) | 0.0447 |

PM-Scl = polymyositis and scleroderma; RNP = ribonucleoprotein; SSc, systemic sclerosis. *P-value calculated by Mann-Whitney rank-sum test for comparison of antibody-positive vs antibody-negative patients.

The prevalence of ATA in our cohort (30.1%) is in line with the numbers published by others, which have varied between 13% and 36% [2,8,9,12,14,15,17,33,34,36,51]. The patients with ATA in our study were more likely to be male and had higher RSSs (Tables 5 and 6). More common in this patient group were digital ulcers, pulmonary fibrosis, dyspnoea, lung restrictive defect and joint involvement (synovitis, contractures) as well as mouth involvement. However, renal involvement, as measured by proteinuria or renal insufficiency, was not more prevalent in this subgroup, a finding reported by most other researchers [8,9,14,15,33,36,51,52] but not all of them [2,34].

The frequency of RNAP antibodies in our cohort was 3.8%, which is at the lower end of the frequency range reported by others, namely, 10% to 25% in North America [33,52-55], 4% to 31.5% in Europe [14,16,33,35,56-59] and 5% to 11% in Japan [34,36,60]. This may have several reasons: (1) Our cohort is composed of a broad spectrum of SSc patients, including patients with milder forms and with overlap or undifferentiated subtypes of the disease, (2) regional differences due to genetic background and/or environmental influences and (3) different techniques used to ascertain the presence of RNAP antibodies. A high mean RSS, reflecting diffuse skin involvement, was evident for patients with anti-RNAP antibodies (Tables 5 and 6) as previously observed [2,14,33,34,36,40,54-60]. In addition, we found creatine kinase (CK) elevation to be more frequently associated with the presence of anti-RNAP antibodies. This has not been noted before; association with muscular involvement has been found to be nonsignificant [14,34,40,53,54] or even inverse [2,36,55] in previous publications. Our result in this study therefore might be a chance finding due to multiple comparisons. We did not find any significant positive association of RNAP antibodies, or any autoantibody evaluated in this study, with renal involvement. In the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma Registry, 'renal involvement' is defined as renal insufficiency in the form of decreased creatinine clearance and/or proteinuria, as well as a consequence of acute renal crisis. The registry did not include renal crisis as a separate item at that time, which may underestimate the possible correlation of antibodies with renal crisis [18]. Within our network, the frequency of renal crisis currently does not exceed 2% to 3% per year (Hunzelmann N, unpublished observation). The prevalence of renal crisis among patients with RNAP antibodies reported in the literature (for review, see Meyer et al. [57]) varies considerably, between 0% and 43%.

Antibodies to fibrillarin (U3-RNP) were most prominent in patients with the diffuse subtype (table 4), which is in accordance with the findings published in previous reports [2,13,34,40,61]. In fact, patients with anti-fibrillarin antibodies, on average, had the highest RSS of all patients in our cohort (Tables 5 and 6). The significance of this finding, however, is less pronounced because of the lower number of patients. The detected anti-fibrillarin antibody frequency of 1.4% was considerably lower than that reported in previous cohorts (2.5% to 19%) [2,13,34,36,40,61-63], which may reflect our broad spectrum of SSc patients that included patients with overlap syndrome and undifferentiated forms, as well as methodological differences and/or the central European background of the patients. Ethnic heterogeneity with a higher frequency of anti-fibrillarin antibodies in black patients has been described previously [2,13,40,61-63]. Our findings of a lower age at disease onset and a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal involvement (Tables 5 and 6) are in line with most previous results [2,36,61,63].

The frequency of PM-Scl antibodies (4.9%) detected in our cohort is in accord with previously published studies in which frequencies between 2% and 6% were noted for SSc patients [1-3,17,33]. These antibodies are most well-known as being typical in patients with dermatomyositis-scleroderma overlap syndrome [1,3]. Accordingly, CK elevation was highly associated with anti-PM-Scl in our cohort. On the other hand, these patients were markedly less likely to have oesophageal involvement (Table 5) and had a low mean ESR (Tables 5 and 6). We found elevated ESR levels in an earlier series of SSc patients with anti-PM-Scl antibodies [32], but others, to the best of our knowledge, did not. (Patients with anti-PM-Scl have rarely been analysed in the large SSc series reported previously.) Therefore, this finding has to be reproduced by independent work in the future. That these patients have a relatively benign prognosis has been mentioned several times before [64-66]. Accordingly, 31% of our patients with anti-PM-Scl antibodies were devoid of any internal organ involvement, compared with 13% of the patients without anti-PM-Scl (P = 0.0023, data not shown).

Antibodies to Ku, when found in SSc patients, are often associated with scleroderma overlap syndrome and with muscular involvement [17,36]. Accordingly, we registered a high OR, but with low significance because of the relatively low patient number, for CK elevation associated with anti-Ku antibody (Table 5). The complete absence of ACA and the occasional presence of ATA described in a large previous study that focused on anti-Ku in patients with SSc [17] were nicely reproduced in our cohort (Table 3). Most of our anti-Ku sera (7 of 10) were positive only by IP and negative in a 'classical' precipitation test with native antigen. In a previous study, on the contrary, a similar test (counterimmunoelectrophoresis) was even more sensitive than a line assay to anti-Ku. A possible explanation for this discrepancy might be the source of the antigen, which was of rabbit origin, in our ID assay. Ku autoantibodies are known to tend to be nonreactive with nonhuman antigens [67].

Antibodies to p25/p23 ('anti-chromo') characterise a patient subset within the group of ACA-positive SSc patients. The clinical findings among these patients were heterogeneous in previous reports. Soriano et al. [49] found an elevated prevalence of erosive arthritis and Furuta et al. [50] reported more interstitial lung disease and liver involvement, whereas Japanese groups [30,31,68] discovered cytopenias, Sjögren's syndrome, overlap with systemic lupus erythematosus and higher ESR levels. We confirmed the relatively strong association with Sjögren's syndrome on the basis of our finding that 20 (71.4%) of 28 patients with p25/p23 antibodies had sicca symptoms, compared to only 41.7% of SSc patients who were negative for these autoantibodies (Table 5). In fact, the weak association of ACA with sicca symptoms (OR = 1.44) (Table 5) lost significance when those patients with co-occurring anti-p25/p23 were eliminated. Likewise, the low mean RSS calculated for ACA-positive patients (6.4) (see Table 6) turned even lower (6.2) after exclusion of patients with anti-p25/p23.

Antibodies to Ro and/or La, as expected and as previously reported [44,45,69,70], were associated with sicca syndrome. This association was only marginally significant; in fact, the antibodies with the most prominent association with the sicca complex were, as mentioned above, anti-p25/p23 antibodies. Anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies showed a particularly high correlation with elevated ESR (Tables 5 and 6). An unexpectedly strong association of anti-Ro60 with pulmonary fibrosis (Table 5) was mainly secondary to the relatively high co-occurrence of this antibody with ATA (see Table 3).

No highly significant differences for any of the autoantibody-defined subgroups could be found for gastric, intestinal or renal involvement, including hypertension and reduced renal function. Furthermore, no significant differences dependent on antibodies against aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases, To, Sm, SL or NOR-90 were detected, probably because of the low numbers of patients positive for these antibodies. Patients without highly SSc-associated antibodies were more often male and less frequently had Raynaud's phenomenon.

Conclusions

The occurrence of SSc-related autoantibodies has never been analysed in such detail in a cohort as large as this one. We have shown that five antigens appear to be sufficient to detect more than 95% of the known SSc-associated autoantibody responses in ANA-positive SSc patients. In more than half of patients with a SSc-associated antibody, other nuclear autoantibodies were detected and a considerable patient group (around 40%) still displayed uncharacterised ANAs of as yet unknown significance.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest comprehensive analysis of the presence of SSc-associated as well as other non-organ-specific autoantibodies in SSc patients that was performed in a single central laboratory and demonstrates the complexity and heterogeneity of the autoimmune response underlying the pathogenesis of this still enigmatic disease.

Abbreviations

ACA: anti-centromere antibody; AMA: antimitochondrial antibody; ANA: antinuclear antibody; ATA: anti-topoisomerase I antibody; CK: creatine kinase; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HR: hazard ratio; ID: immunodiffusion; IP: immunoprecipitation; OR: odds ratio; RNAP: RNA polymerase; RSS: Rodnan skin score; SSc: systemic sclerosis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RM designed the study, performed the serological analyses, had full access to all of the data in the study, analysed the data, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. EG designed the study, was responsible for overall project management, enrolled patients for the network, and contributed data from one participating centre. TK designed the study and was responsible for overall project management. PM, GR, MM, FR, MB, MW, NB, RH, AK, CS, AJ, CP, CF, MS, PL, RS, ESL, CS and IF enrolled patients for the network and contributed the data from the participating centres. IM and UML were responsible for overall project management, enrolled patients for the network and contributed the data from the participating centres. NH interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript, was responsible for overall project management and designed the study. All authors critically revised the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Rudolf Mierau, Email: mierau.rmn@t-online.de.

Pia Moinzadeh, Email: pia.moinzadeh@uk-koeln.de.

Gabriela Riemekasten, Email: gabriela.riemekasten@charite.de.

Inga Melchers, Email: inga.melchers@uniklinik-freiburg.de.

Michael Meurer, Email: Michael.Meurer@uniklinikum-dresden.de.

Frank Reichenberger, Email: Frank.Reichenberger@innere.med.uni-giessen.de.

Michael Buslau, Email: m.buslau@reha-rhf.ch.

Margitta Worm, Email: margitta.worm@charite.de.

Norbert Blank, Email: Norbert.Blank@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

Rüdiger Hein, Email: Ruediger.Hein@lrz.tum.de.

Ulf Müller-Ladner, Email: u.mueller-ladner@kerckhoff-klinik.de.

Annegret Kuhn, Email: kuhnan@uni-muenster.de.

Cord Sunderkötter, Email: cord.sunderkoetter@ukmuenster.de.

Aaron Juche, Email: Juche@johannit-trbr.de.

Christiane Pfeiffer, Email: Christiane.pfeiffer@uniklinik-ulm.de.

Christoph Fiehn, Email: c.fiehn@rheumazentrum-baden.de.

Michael Sticherling, Email: michael.sticherling@uk-erlangen.de.

Percy Lehmann, Email: plehmann@wuppertal.helios-kliniken.de.

Rudolf Stadler, Email: rudolf.stadler@klinikum-minden.de.

Eckhard Schulze-Lohoff, Email: e.schulze-lohoff@kkd.de.

Cornelia Seitz, Email: cseitz@med.uni-goettingen.de.

Ivan Foeldvari, Email: foeldvari@uke.uni-hamburg.de.

Thomas Krieg, Email: thomas.krieg@Uni-Koeln.de.

Ekkehard Genth, Email: mail@ekkehard-genth.de.

Nicolas Hunzelmann, Email: Nico.Hunzelmann@uni-koeln.de.

Acknowledgements

The expert technical assistance of Marie-Claire Vondegracht and Rita Bernstein is gratefully acknowledged. Furthermore, we are indebted to Dr M Blüthner, Laboratory Prof Seelig, Karlsruhe, Germany, for confirming the anti-To antibodies; to Dr C Will and Professor R Lührmann, Marburg, Germany, for identification of the anti-U11 RNP antibodies; and to Dr EK Chan, Gainesville, FL, USA; Prof B Liedvogel, Diarect, Freiburg, Germany; and Dr W Schlumberger, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany, for supplying rabbit anti-sera to p25/p23, recombinant PM-Scl antigens, and investigational anti-fibrillarin ELISA kits, respectively. We also thank A Fehr and B Damm for data acquisition and management and Hildegard Christ and PD Dr Martin Hellmich for statistical advice. This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (grants 01GM0310 and 01GM0630).

References

- Cepeda EJ, Reveille JD. Autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis and fibrosing syndromes: clinical indications and relevance. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:723–732. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000144760.37777.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen VD. Autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JG, Fritzler MJ. Update on autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:580–591. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282e7d8f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi AT, Rodnan GP, Medsger TA Jr, Altman RD, D'Angelo WAD, Fries JF, LeRoy EC, Kirsner AB, MacKenzie AH, McShane DJ, Myers AR, Sharp GC. the Subcommittee for Scleroderma Criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581–590. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy EC, Medsger TA Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1573–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig M, Joyal F, Fritzler MJ, Roussin A, Abrahamowicz M, Boire G, Goulet JR, Rich É, Grodzicky T, Raymond Y, Senécal JL. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage are independent predictive factors for the progression of Raynaud's phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a twenty-year prospective study of 586 patients, with validation of proposed criteria for early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3902–3912. doi: 10.1002/art.24038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elicha Gussin HA, Ignat GP, Varga J, Teodorescu M. Anti-topoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70) antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:376–383. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200102)44:2<376::AID-ANR56>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen VD, Powell DL, Medsger TA Jr. Clinical correlations and prognosis based on serum autoantibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:196–203. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, Sebastiani M, Michelassi C, La Montagna G, Bullo A, Cazzato M, Tirri E, Storino F, Giuggioli D, Cuomo G, Rosada M, Bombardieri S, Todesco S, Tirri G. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine. 2002;81:139–153. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scussel-Lonzetti L, Joyal F, Raynauld JP, Roussin A, Rich É, Goulet JR, Raymond Y, Senécal JL. Predicting mortality in systemic sclerosis: analysis of a cohort of 309 French Canadian patients with emphasis on features at diagnosis as predictive factors for survival. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:154–167. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes MD, Lacey JV Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J, Gillespie BW, Cooper B, Laing TJ, Schottenfeld D. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246–2255. doi: 10.1002/art.11073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker UA, Tyndall A, Czirják L, Denton C, Farge-Bancel D, Kowal-Bielecka O, Müller-Ladner U, Bocelli-Tyndall C, Matucci-Cerinic M. EUSTAR. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials And Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:754–763. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett FC, Reveille JD, Goldstein R, Pollard KM, Leaird K, Smith EA, LeRoy EC, Fritzler MJ. Autoantibodies to fibrillarin in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): an immunogenetic, serologic, and clinical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1151–1160. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn CC, Denton CP, Shi-Wen X, Knight C, Black CM. Anti-RNA polymerases and other autoantibody specificities in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:15–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen S, Halberg P, Ullman S, van Venrooij WJ, Høier-Madsen M, Wiik A, Petersen J. Clinical features and serum antinuclear antibodies in 230 Danish patients with systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:39–45. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselstrand R, Scheja A, Shen GQ, Wiik A, Akesson A. The association of antinuclear antibodies with organ involvement and survival in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:534–540. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozman B, Cucnik S, Sodin-Semrl S, Czirják L, Varjú C, Distler O, Huscher D, Aringer M, Steiner G, Matucci-Cerinic M, Guiducci S, Stamenkovic B, Stankovic A, Kveder T. Prevalence and clinical associations of anti-Ku antibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis: a European EUSTAR-initiated multi-centre case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1282–1286. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzelmann N, Genth E, Krieg T, Lehmacher W, Melchers I, Meurer M, Moinzadeh P, Müller-Ladner U, Pfeiffer C, Riemekasten G, Schulze-Lohoff E, Sunderkötter C, Weber M, Worm M, Klaus P, Rubbert A, Steinbrink K, Grundt B, Hein R, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Hinrichs R, Walker K, Szeimies RM, Karrer S, Müller A, Seitz C, Schmidt E, Lehmann P, Foeldvári I, Reichenberger F. Registry of the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma et al. The registry of the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma: frequency of disease subsets and patterns of organ involvement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1185–1192. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzelmann N, Moinzadeh P, Genth E, Krieg T, Lehmacher W, Melchers I, Meurer M, Müller-Ladner U, Olski TM, Pfeiffer C, Riemekasten G, Schulze-Lohoff E, Sunderkötter C, Weber M. German Network for Systemic Scleroderma Centers. High frequency of corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy in patients with systemic sclerosis despite limited evidence for efficacy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R30. doi: 10.1186/ar2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA Jr, Rowell N, Wollheim F. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RM. Scleroderma overlap syndromes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16:185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope JE. Scleroderma overlap syndromes. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:704–710. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200211000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA Jr. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444–451. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<444::AID-ANR27>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano M, Valentini G, Migliaresi S, Picillo U, Vatti M. Different antibody patterns and different prognoses in patients with scleroderma with various extent of skin sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:911–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón GS. Unclassified or undifferentiated connective tissue disease. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2000;14:125–137. doi: 10.1053/berh.1999.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy EC, Maricq HR, Kahaleh MB. Undifferentiated connective tissue syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:341–343. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack U, Conrad K, Csernok E, Frank I, Hiepe F, Krieger T, Kromminga A, von Landenberg P, Messer G, Witte T, Mierau R. German EASI (European Autoimmunity Standardization Initiative) Autoantibody detection using indirect immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:166–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey GR, Black CM, Maddison PJ, McHugh NJ. Characterization of antinucleolar antibody reactivity in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relatives. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakata M, Suwa A, Takada T, Sato S, Nagai S, Genth E, Song YW, Mimori T, Targoff IN. Clinical and immunogenetic features of patients with autoantibodies to asparaginyl-transfer RNA synthetase. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1295–1303. doi: 10.1002/art.22506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro Y, Yamada T, Iwai T, Sugimoto K. Epitope analysis of chromo antigen and clinical features in a subset of patients with anti-centromere antibodies. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:147–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00351162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai T, Muro Y, Sugimoto K, Matsumoto Y, Ohashi M. Clinical features of anti-chromo antibodies associated with anti-centromere antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:285–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genth E, Mierau R, Genetzky P, von Mühlen CA, Kaufmann S, von Wilmowsky H, Meurer M, Krieg T, Pollmann HJ, Hartl PW. Immunogenetic associations of scleroderma-related antinuclear antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:657–665. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer OC, Fertig N, Lucas M, Somogyi N, Medsger TA Jr. Disease subsets, antinuclear antibody profile, and clinical features in 127 French and 247 US adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:104–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi Y, Hasegawa M, Fujimoto M, Matsushita T, Komura K, Kaji K, Kondo M, Nishijima C, Hayakawa I, Ogawa F, Kuwana M, Takehara K, Sato S. The clinical relevance of serum antinuclear antibodies in Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis. Brit J Dermatol. 2008;158:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning GC, Welsh KI, Bunn C, du Bois RM, Black CM. HLA associations in three mutually exclusive autoantibody subgroups in UK systemic sclerosis patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:201–207. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana M, Kaburaki J, Okano Y, Tojo T, Homma M. Clinical and prognostic associations based on serum antinuclear antibodies in Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:75–83. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick T, Mierau R, Bartz-Bazzanella P, Alavi M, Stoyanova-Scholz M, Kindler J, Genth E. Coexistence of anti-topoisomerase 1 and anti-centromere antibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:121–127. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke K, Becker MO, Brueckner CS, Meyer W, Janssen A, Schlumberger W, Hiepe F, Burmester GR, Riemekasten G. Anticentromere-A and anticentromere-B antibodies show high concordance and similar clinical associations in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:2548–2552. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliddon AE, Dore CJ, Dunphy J, Betteridge Z, McHugh NJ, Maddison PJ. Antinuclear antibodies and clinical associations in a British cohort with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:702–705. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkner D, Wilson J, Fertig N, Clawson K, Medsger TA Jr, Morel PA. Studies of HLA-DR and DQ alleles in systemic sclerosis patients with autoantibodies to RNA polymerases and U3-RNP (fibrillarin) J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1196–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiev KP, Diot E, Clerson P, Dupuis-Siméon F, Hachulla E, Hatron PY, Constans J, Cirstéa D, Farge-Bancel D, Carpentier PH. Clinical features of scleroderma patients with or without prior or current ischemic digital ulcers: post-hoc analysis of a nationwide multicenter cohort (ItinérAIR-Sclérodermie) J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1470–1476. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderkötter C, Herrgott I, Brückner C, Moinzadeh P, Pfeiffer C, Gerss J, Hunzelmann N, Böhm M, Krieg T, Müller-Ladner U, Genth E, Schulze-Lohoff E, Meurer M, Melchers I, Riemekasten G. DNSS Centers. Comparison of patients with and without digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: detection of possible risk factors. Brit J Dermatol. 2009;160:835–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khimdas S, Harding S, Bonner A, Zummer B, Baron M, Pope J. Canadian Scleroderma Research Group. Associations with digital ulcers in a large cohort of systemic sclerosis: results from the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group registry. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:142–149. doi: 10.1002/acr.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama Y, Tanaka M, Takeishi M, Adachi D, Mimori A, Suzuki T. Clinical, serological and genetic study in patients with CREST syndrome. Intern Med. 2000;39:451–456. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki S, Asanuma H, Nishiyama S, Yoshinaga Y. Clinical and serological heterogeneity in patients with anticentromere antibodies. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1488–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picha L, Pakas I, Guialis A, Moutsopoulos HM, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG. Comparative qualitative and quantitative analysis of scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) serologic immunoassays. J Autoimmun. 2008;31:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasini B, Gagetta M, Rossi V, Ferrari P. Rheumatic disorders and primary biliary cirrhosis: an appraisal of 170 Italian patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1046–1049. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigamonti C, Shand LM, Feudjo M, Bunn CC, Black CM, Denton CP, Burroughs AK. Clinical features and prognosis of primary biliary cirrhosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Gut. 2006;55:388–394. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.075002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano E, Whyte J, McHugh NJ. Frequency and clinical associations of anti-chromo antibodies in connective tissue disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:666–670. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.10.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta K, Hildebrandt B, Matsuoka S, Kiyosawa K, Reimer G, Luderschmidt C, Chan EKL, Tan EM. Immunological characterization of heterochromatin protein p25β autoantibodies and relationship with centromere autoantibodies and pulmonary fibrosis in systemic scleroderma. J Mol Med (Berl) 1998;76:54–60. doi: 10.1007/s109-1998-8104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke K, Dähnrich C, Brückner CS, Huscher D, Becker M, Jansen A, Meyer W, Egerer K, Hiepe F, Burmester GR, Schlumberger W, Riemekasten G. Diagnostic value of anti-topoisomerase I antibodies in a large monocentric cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B, Mayes MD, Arnett FC, Del Junco D, Reveille JD, Gonzalez EB, Draeger HT, Perry M, Hendiani A, Anand KK, Assassi S. HLA-DRB1*0407 and *1304 are risk factors for scleroderma renal crisis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:530–534. doi: 10.1002/art.30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MG, Wang RJ, Yangco DT, Sharp GC, Komatireddy GR, Hoffman RW. Analysis of autoantibodies against RNA polymerases using immunoaffinity-purified RNA polymerase I, II, and III antigen in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;89:71–78. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago M, Baron M, Hudson M, Burlingame RW, Fritzler MJ. Antibodies to RNA polymerase III in systemic sclerosis detected by ELISA. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1528–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano Y, Steen VD, Medsger TA Jr. Autoantibody reactive with RNA polymerase III in systemic sclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1005–1013. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-10-199311150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoni A, Rossi P, Salvini R, Bobbio-Pallavicini F, Caporali R, Montecucco C. Autoantibodies to RNA-polymerases in Italian patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O, De Chaisemartin L, Nicaise-Roland P, Cabane J, Tubach F, Dieude P, Hayem G, Palazzo E, Chollet-Martin S, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody prevalence and associated clinical manifestations in a large series of French patients with systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:125–130. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey GR, Butts S, Rands AL, Patel Y, McHugh NJ. Clinical and serological associations with anti-RNA polymerase antibodies in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airo' P, Ceribelli A, Cavazzana I, Taraborelli M, Zingarelli S, Franceschini F. Malignancies in Italian patients with systemic sclerosis positive for anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1329–1334. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Ishikawa O, Ihn H, Endo H, Kawaguchi Y, Sasaki T, Goto D, Takahashi K, Takahashi H, Misaki Y, Mimori T, Muro Y, Yazawa N, Sato S, Takehara K, Kuwana M. Clinical usefulness of anti-RNA polymerase III antibody measurement by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1570–1574. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tormey VJ, Bunn CC, Denton CP, Black CM. Anti-fibrillarin antibodies in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:1157–1162. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reveille JD, Fischbach M, McNearney T, Friedman AW, Aguilar MB, Lisse J, Fritzler MJ, Ahn C, Arnett FC. Systemic sclerosis in 3 US ethnic groups: a comparison of clinical, sociodemographic, serologic, and immunogenetic determinants. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;30:332–346. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2001.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal R, Lucas M, Fertig N, Oddis CV, Medsger TA Jr. Anti-U3 RNP autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1112–1118. doi: 10.1002/art.24409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddis CV, Okano Y, Rudert WA, Trucco M, Duquesnoy RJ, Medsger TA Jr. Serum autoantibody to the nucleolar antigen PM-Scl: clinical and immunogenetic associations. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1211–1217. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marguerie C, Bunn CC, Copier J, Bernstein RM, Gilroy JM, Black CM, So AK, Walport MJ. The clinical and immunogenetic features of patients with autoantibodies to the nucleolar antigen PM-Scl. Medicine (Baltimore) 1992;71:327–336. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandergheynst F, Ocmant A, Sordet C, Humbel RL, Goetz J, Roufosse F, Cogan E, Sibilia J. Anti-PM/scl antibodies in connective tissue disease: clinical and biological assessment of 14 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:129–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targoff IN. Humoral immunity in polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:116S–123S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12356607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katano K, Kawano M, Koni I, Sugai S, Muro Y. Clinical and laboratory features of anticentromere antibody positive primary Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2238–2244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osial TA Jr, Whiteside TL, Buckingham RB, Singh G, Barnes EL, Pierce JM, Rodnan GP. Clinical and serologic study of Sjögren's syndrome in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:500–508. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosos AA, Andonopoulos AP, Costopoulos JS, Stavropoulos ED, Papadimitriou CS, Moutsopoulos HM. Sjögren's syndrome in progressive systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:965–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana M, Okano Y, Pandey JP, Silver RM, Fertig N, Medsger TA Jr. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of anti-RNA polymerase III antibody: analytical accuracy and clinical associations in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2425–2432. doi: 10.1002/art.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki Y, Honkanen-Scott M, Hernandez L, Ikeda K, Barker T, Bubb MR, Narain S, Richards HB, Chan EK, Reeves WH, Satoh M. Nucleolar staining cannot be used as a screening test for the scleroderma marker anti-RNA polymerase I/III antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3051–3056. doi: 10.1002/art.22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler M, Raijmakers R, Dähnrich C, Blüthner M, Fritzler MJ. Clinical evaluation of autoantibodies to a novel PM/Scl peptide antigen. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R704–R713. doi: 10.1186/ar1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam AC, Steitz JA. Rare scleroderma autoantibodies to the U11 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein and to the trimethylguanosine cap of U small nuclear RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6781–6785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feghali-Bostwick C, Medsger TA Jr, Wright TM. Analysis of systemic sclerosis in twins reveals low concordance for disease and high concordance for the presence of antinuclear antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1956–1963. doi: 10.1002/art.11173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders WS, Chue C, Goebl M, Craig C, Clark RF, Powers JA, Eissenberg JC, Elgin SC, Rothfield NF, Earnshaw WC. Molecular cloning of a human homologue of Drosophila heterochromatin protein HP1 using anti-centromere autoantibodies with anti-chromo specificity. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:573–582. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.2.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta K, Chan EK, Kiyosawa K, Reimer G, Luderschmidt C, Tan EM. Heterochromatin protein HP1Hsβ(p25β) and its localization with centromeres in mitosis. Chromosoma. 1997;106:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s004120050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick T, Mierau R, Sternfeld R, Weiner EM, Genth E. Clinical relevance and HLA association of autoantibodies against the nucleolus organizer region (NOR-90) J Rheumatol. 1995;22:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostecki C, Guldner HH, Netter HJ, Will H. Isolation and characterization of cDNA encoding a human nuclear antigen predominantly recognized by autoantibodies from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Immunol. 1990;145:4338–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]