Abstract

G-protein coupled receptor interacting scaffold protein (GISP) is a multi-domain, brain-specific protein derived from the A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP)-9 gene. Using yeast two-hybrid screens to identify GISP interacting proteins we isolated the SUMO conjugating enzyme Ubc9. GISP interacts with Ubc9 in vitro, in heterologous cells and in neurons. SUMOylation is a post-translational modification in which the small protein SUMO is covalently conjugated to target proteins, modulating their function. Consistent with its interaction with Ubc9, we show that GISP is SUMOylated by both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 in both in vitro SUMOylation assays and in mammalian cells. Intriguingly, SUMOylation of GISP in neurons occurs in an activity-dependent manner in response to chemical LTP. These data suggest that GISP is a novel neuronal SUMO substrate whose SUMOylation status is modulated by neuronal activity.

Keywords: GISP, Ubc9, SENP1, AKAP, SUMO

1. Introduction

GISP is a brain-specific protein that has 90% homology with human AKAP450 that was initially identified in a screen for proteins that interact with the C-terminus of the GABAB receptor subunit GABAB1 [1]. GISP binds directly to the GABAB1 subunit and its coexpression in HEK293 cells with GABAB1 and GABAB2 subunits significantly up-regulates the surface expression of recombinant GABAB receptor complexes. We have shown previously that GISP also binds to TSG101, an integral component of the ESCRT machinery that is involved in the sorting of membrane proteins for lysosomal degradation. Through this interaction, GISP functions as a neuron-specific inhibitor of TSG101-dependent membrane protein degradation since GISP overexpression upregulates the expression of a number of receptor proteins [2,3].

To identify additional GISP interactors and to explore the potential mechanism of GISPs regulation of protein stability we performed a yeast 2-hybrid screen using GISP as bait. We isolated Ubc9, the sole reported conjugating enzyme of the SUMOylation pathway. SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like MOdifier) proteins are ~11 kDa proteins that can be covalently conjugated to lysine residues in target proteins, altering the biochemical and/or functional properties of the modified protein. Three SUMO paralogues (SUMO-1–3) have been identified in brain and several hundred targets of SUMOylation have been reported. SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 differ by just three N-terminal amino acids but they share only ~50% sequence identity to SUMO-1 [4].

Proteins are SUMOylated via an enzymatic cascade analogous to ubiquitination. Briefly, SUMO proteins are first activated by the action of an E1 ‘activating’ enzyme, which passes the activated SUMO to the E2 ‘conjugating’ enzyme which, usually but not always, in conjunction with an E3 ‘ligase’ enzyme, catalyses SUMO conjugation to the substrate (reviewed in [4]). Importantly, Ubc9 is the only known E2 SUMO conjugating enzyme and Ubc9 itself binds directly to the consensus SUMOylation motif on substrate proteins [5,6]. The target protein consensus motif comprises ψKxD/E, where ψ is a large hydrophobic residue, K is the target lysine, x can be any residue, and D/E are aspartate or glutamic acid (acidic residues). Although the majority of known SUMO substrates are modified within a consensus motif [7], SUMOylation can also occur at lysines outside this motif and not all ψKxD/E motifs are SUMOylated.

Here we demonstrate that GISP interacts with Ubc9 in both heterologous systems and brain. Further, we identify GISP as a novel SUMO substrate that can be modified at multiple sites by both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 and, importantly, show that GISP SUMOylation is regulated by neuronal activity.

2. Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

Bacterial expression constructs encoding GST-GISP fragments and GFP-SENP1 viral constructs have been described previously [2,8]. Full-length FLAG-GISP and GFP-GISP were produced by cloning GISP into pCMV-FLAG (Invitrogen) or pEGFP-C2 (Clontech), respectively, after amplification by PCR. YFP-SUMO-1 constructs were a gift from Frauke Melchior (ZMBH, Heidelberg, Germany). YFP-SUMO-2 constructs were produced by PCR amplification and cloning into pEYFP-C1 (Clontech). FLAG-Ubc9 and GST-Ubc9 were produced by PCR amplification and cloning into pCMV-FLAG (Invitrogen) or pGEX4t-1 (Amersham), respectively. The bacterial SUMOylation assay vector was a gift from Hisato Saitoh (Kumamoto University, Japan). The fidelity of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Yeast 2-hybrid screening and analysis of Ubc9-GISP interaction

GISP (residues G102–Y1059; Fig. 1A) was subcloned into the pBTM-116ADE vector and used to screen an adult rat brain cDNA library (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae L-40 reporter strain as described previously [9].

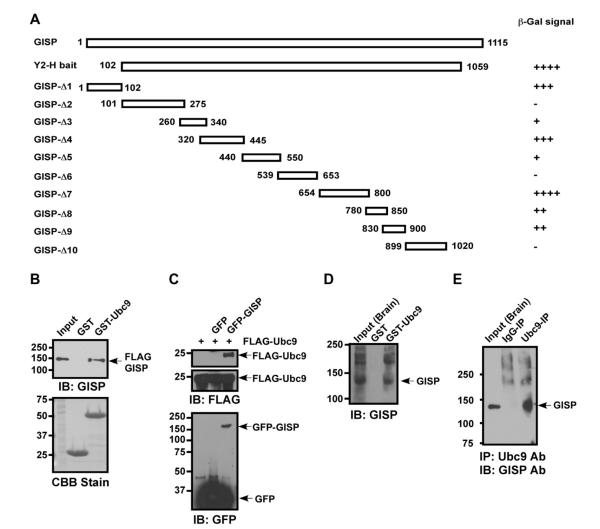

Fig. 1.

GISP interacts with Ubc9. (A) Ubc9 was identified as a GISP interactor from a yeast two-hybrid screen using GISP as a bait. Targeted yeast two-hybrid assays were used to identify the regions of GISP responsible for binding to Ubc9. (B) FLAG-GISP was transfected into COS-7 cells and lysate mixed with glutathione beads bound to GST or GST-Ubc9. (C) GFP-GISP was transfected into COS-7 cells along with FLAG-Ubc9 and GFP-GISP immunoprecipitated with GFP-trap A beads. Top panel, IP GFP blot FLAG, middle panel are inputs blotted for FLAG and bottom panel is the IP from the top panel blotted for GFP. (D) Rat brain homogenate was incubated with either GST- or GST-Ubc9 immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads followed by immunoblotting for GISP. (E) Ubc9 was immunoprecipitated from the cytosolic fraction of rat brain lysate and immunoprecipitates immunoblotted for GISP.

COS-7 cell culture, transfection and lysis

COS-7 cells were cultured as previously described [10]. Cells were transfected using TransIT reagent (Mirus) and incubated for 24–48 h prior to harvesting. Transfected cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Gibco) and scraped into lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% triton X-100, pH 7.4, containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) before being briefly sonicated and solubilised for 1 h at 4 °C. Lysates were then centrifuged at 16,000g for 20 min and the pellets were discarded.

Co-immunoprecipitation from COS-7 cells

GFP/YFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated using GFP-trap A beads (Chromo-Tek), as described previously [11].

Co-immunoprecipitation from adult rat brain

The enriched cytosol fraction from a whole adult rat brain was re-suspended in lysis buffer and sonicated. This fraction was then solubilised for 2 h at 4 °C before being cleared by centrifugation at 16,000g. One millilitre of lysate was then diluted in 9 ml of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4, containing protease inhibitors) and 2.5 μg of rabbit anti-Ubc9 (Sigma) antibody or control rabbit IgG (Neomarkers) were added. Samples were mixed on an end-over-end shaker for 2 h at 4 °C. Next, 20 μl of pre-washed protein-G beads (Sigma) were added and the samples were mixed for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer (diluted 1:10 with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4, containing protease inhibitors) before boiling in 2 × Laemmli buffer.

GST pull-downs

GST pull-down experiments were performed as previously described [1]. In brief, each GST fusion protein was expressed in bacteria, lysed and then affinity purified using glutathione-agarose beads (Amersham). One microgram of purified fusion protein was then immobilised on glutathione-agarose beads and mixed with either lysate from COS-7 cells expressing FLAG-GISP or lysate from rat brain for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed extensively and boiled in 2 Laemmli buffer.

Bacterial SUMOylation assay

The bacterial SUMOylation assay was performed as described previously [12].

ChemLTP

Cultured hippocampal neurons were washed with LTP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 30 mM glucose, 0.5 μM TTX, 1 μM strychnine, 20 μM bicuculline (pH 7.4)) as previously described [13,14]. Glycine (200μM) was added to the cells for 3 min at 37 °C, then replaced with LTP buffer and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting performed using goat polyclonal antibodies to GISP (made in-house; 1 μg/ml) and GST (Amersham; 1:10,000), mouse monoclonal anti-GFP (Roche, 1:1000), rabbit anti-Ubc9 antibody (Sigma, 1 μg/ml), mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (Clone M2; Sigma; 1:2500 dilution) and mouse monoclonal anti-SUMO-1 (Clone D-11; Santa Cruz; 2 μg/ml).

Sindbis virus production

Sindbis viruses encoding GFP-SENP1 (wild type or C603S) were produced as described previously [8].

Immunocytochemistry and confocal imaging

Hippocampal neurons were fixed for 20 min with paraformaldehyde (2%), permeabilized with digitonin (10 min; Sigma D141), incubated with 10% horse serum (20 min) and incubated with anti-GISP (goat, 1:100), anti-Ubc9 (rabbit, 1:50; Santa Cruz) and anti-SUMO-1 (mouse, 1:100; Santa Cruz) for 60 min at room temperature. Neurons were labelled with Cy2-anti-goat, Cy3-anti-rabbit and Cy5-anti-mouse antibodies. Confocal images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope and quantified in ImageJ (NIH). The degree of GISP/SUMO-1 and GISP/Ubc9 colocalisation was normalised to the control condition. At least 10 cells for each condition and 3–5 regions of interest per cell from three independent experiments were analysed using identical confocal acquisition parameters. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. and significance was determined using unpaired t-tests.

3. Results

3.1. GISP interacts with Ubc9 in brain

We used the GISP clone originally obtained from a GABAB1 yeast 2-hybrid screen (GISP residues G102–Y1059; [1]) as a bait to screen an adult rat brain cDNA library and Ubc9 was isolated as a strong interacting partner. To define the site(s) of interaction we tested for yeast 2-hybrid interactions between the isolated Ubc9 clone and a sequential series of overlapping GISP truncations (GISP-Δ1–GISP-Δ10). Potential interaction sites were detected in several truncations (Fig. 1A).

To validate the interaction between GISP and Ubc9 we next expressed epitope-tagged GISP in COS-7 cells and performed pull-down assays with GST-Ubc9 (Fig. 1B). FLAG-GISP bound robustly to GST-Ubc9 but not to GST alone, indicating a specific interaction between the two proteins. In addition to pull-downs, GFP-GISP was cotransfected into COS-7 cells along with FLAG-Ubc9 and co-immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that GISP and Ubc9 form a complex in mammalian cells (Fig. 1C).

The interaction between GISP and Ubc9 in brain was verified by both GST-Ubc9 pull-down assays and by co-immunoprecipitation of GISP with a Ubc9-specific antibody (Fig. 1D, E). Native GISP bound strongly to GST-Ubc9 and was present in high amounts in co-immunoprecipitation experiments performed with an anti-Ubc9 antibody. Interestingly, in these experiments a number of higher molecular weight species were also detected with the GISP antibody, raising the possibility that these higher molecular weight forms represent SUMOylated forms of GISP.

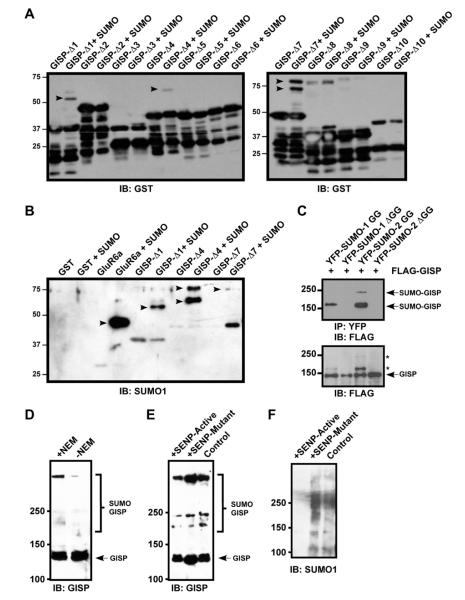

3.2. GISP is SUMOylated in vitro and in vivo

We next confirmed that GISP is a novel neuronal SUMO substrate and set out to define the SUMOylation site(s). Sequence analysis using SUMOplot (Abgent) identified multiple possible SUMOylation sites in GISP (data not shown). We generated GST-GISP truncation constructs corresponding to those used in the yeast two-hybrid assays (Fig. 1A) and tested for SUMOylation in a bacterial SUMOylation assay [15]. As shown in Fig. 2A, several of the truncations were SUMOylated, suggesting that there are multiple SUMOylatable sites present in GISP. Consistent with the yeast two-hybrid data, the fragments of GISP that interacted with Ubc9 were found to be SUMOylated in the bacterial SUMOylation assay. Further, purification of these GST-GISP fragments after SUMOylation in bacteria followed by SUMO-1 immunoblotting confirmed that the higher molecular weight forms observed in Fig. 2A represent SUMOylated forms of the GST-GISP fragments (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

GISP is a novel neuronal SUMOylation substrate. (A) GST-GISP truncation constructs were expressed in bacteria either with or without a plasmid expressing the SUMO machinery. Bands representing SUMOylated GISP fragments are indicated by arrows. (B) Samples from (A) were purified on glutathione beads followed by immunoblotting for SUMO-1. GST and GluR6 were also included as negative or positive controls, respectively. (C) COS-7 cells were transfected with FLAG-GISP and either conjugatable or non-conjugatable (ΔGG) YFP-SUMO-1 or YFP-SUMO-2. YFP-SUMO-modified proteins were isolated using GFP-trap A beads and immunoblotted for FLAG (top panel). Bands indicating SUMOylated GISP are indicated. Bottom panel shows total lysates blotted for FLAG-GISP. Note the detection of higher molecular weight forms of GISP (marked by asterisks) upon coexpression with conjugatable SUMO-1 and SUMO-2, which correspond to those seen in the upper panel. (D) Cultured cortical neurons were lysed ± NEM (20 mM) and 50 μg of extract was immunoblotted for GISP. (E) Cultured cortical neurons were infected with Sindbis virus expressing GFP-tagged catalytic domains of either SENP1 (SENP-Active) or its inactive point mutant (C603S; SENP-Mutant). 50 μg of lysate was then subjected to immunoblotting for GISP. (F) Samples from E were immunoblotted for SUMO-1 to ensure the activity of overexpressed SENP1.

We next assessed if full-length GISP was SUMOylated in mammalian cells by expressing FLAG-GISP together with YFP-SUMO-1 or YFP-SUMO-2 or non-conjugatable SUMO mutants lacking the C-terminal diglycine motif required for conjugation, in COS-7 cells. Both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 conjugated to GISP yielding higher molecular weight species of ~180 kDa. In addition, with SUMO-2 a much higher molecular weight species of >250 kDa was detected, presumably representing either modification of GISP at multiple sites by SUMO-2, or the formation of SUMO-2 chains conjugated to GISP. Consistent with these higher molecular weight species representing SUMO modification of GISP, these bands were absent when GISP was coexpressed with the non-conjugatable SUMODGG mutants (Fig. 2C).

To define whether GISP is SUMOyated in brain, we probed rat brain lysate prepared in the presence or absence of NEM (20 mM) with an anti-GISP antibody to determine if higher molecular weight bands are detectable. NEM is a cysteine alkylating agent that inhibits the SENP enzymes required for deSUMOylation. Higher molecular weight species of GISP were detected in the presence of NEM, but were greatly decreased when NEM was omitted. Interestingly, multiple higher molecular weight forms of GISP were apparent with major species at ~200, ~250 and >250 kDa (Fig. 2D).

To verify the higher molecular weight species represented SUMO-conjugated GISP, we virally expressed a GFP-tagged catalytic domain of the deSUMOylating enzyme SENP1 (SENP-Active), which removes both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2/3 from substrate proteins, or an inactive mutant SENP1(C603S) (SENP-Mutant) in cultured cortical neurons and blotted for GISP. Expression of active SENP1 decreased both total SUMOylation and the intensity of the higher molecular weight GISP bands whereas inactive SENP1 did not (Fig. 2E, F), suggesting these bands represent SUMO-modified GISP.

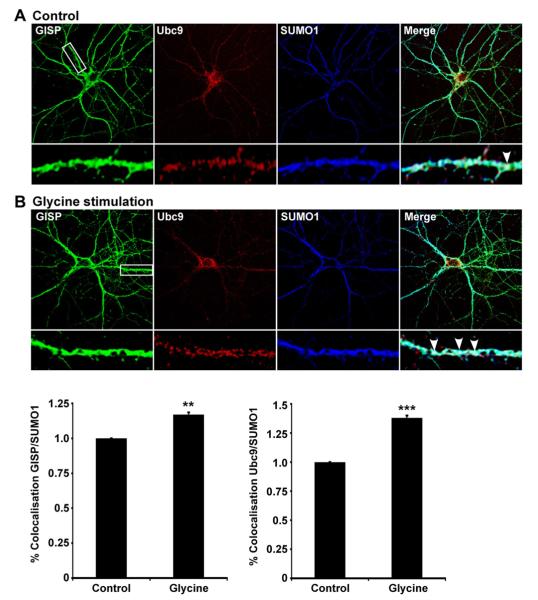

3.3. GISP, Ubc9 and SUMO-1 colocalise in cultured hippocampal neurons

We next determined whether GISP, Ubc9 and SUMO-1 colocalise in cultured hippocampal neurons using specific antibodies and fixed cell imaging. As shown in Fig. 3A, GISP and SUMO-1 show an extensive distribution throughout the soma and dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurones. Ubc9 is also present in dendrites and there are puncta where all three proteins colocalise. These imaging data are consistent with the biochemical results and indicate that the machinery required for SUMOylation is widely distributed throughout neuronal processes allowing the dynamic control of protein SUMOylation.

Fig. 3.

Colocalisation of GISP and SUMO-1 is enhanced by chem-LTP. (A) Example fluorescence image of cultured hippocampal neurons (18–21DIV) stained for GISP (green), Ubc9 (red) and SUMO-1 (blue). Boxes indicate the magnified areas of dendrites shown in the lower panel used for quantification. (B) Colocalisation of GISP/SUMO-1 and Ubc9/ SUMO-1 in dendrites after chem-LTP. Colocalisation is shown as the percentage of GISP or Ubc9 immunoreactivity co-localizing with SUMO-1 signal. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4. Chemical LTP enhances the colocalisation of GISP with SUMO-1

Given that GISP is SUMOylated and that both the SUMO machinery and GISP are present in neuronal processes, we wondered whether SUMOylation of GISP is regulated by neuronal activity. We therefore stimulated cultured hippocampal neurons with glycine to induce a form of chemical LTP [13]. Intriguingly, chem-LTP increased the colocalisation of GISP with SUMO-1 (Fig. 3B), implying both that the interaction of GISP with Ubc9 and consequent SUMOylation are enhanced by this stimulation of neuronal activity. Further, chem-LTP enhanced the colocalisation of Ubc9 and SUMO-1, suggesting a possible enhancement of Ubc9 activation under these conditions. These data suggest that there exists synaptic activity-dependent regulation of GISP SUMOylation.

4. Discussion

SUMOylation regulates multiple aspects of cell function and its role in neurons has received increasing attention in recent years with the identification of a number of neuronal SUMO substrates [4]. However, in many cases the functional significance of SUMOylation has remained elusive. Nonetheless, dysfunction of the SUMOylation pathway has been implicated in the molecular and cellular dysfunction associated with numerous neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [16].

Here, we have identified GISP as a novel neuronal SUMO substrate through the isolation of the sole SUMO conjugating enzyme, Ubc9, in a yeast two-hybrid assay. GISP binds Ubc9 in both heterologous systems and brain, and can be SUMOylated by both SUMO-1 and SUMO-2. In addition, GISP, Ubc9 and SUMO-1 colocalise in neuronal processes, and the extent of colocalisation is regulated by neuronal activity, suggesting that GISP undergoes activity-dependent SUMOylation.

Interestingly, a significant proportion of SUMOylated GISP seems to have an apparent Mr of ~400 kDa, nearly three times that of unmodified GISP. A possible explanation for this may be that GISP undergoes multiple mono-SUMOylation at different lysines, as suggested by the presence of multiple SUMOylatable lysines in the bacterial SUMOylation assay (Fig. 2A). Alternatively, it is possible that GISP is conjugated with poly-SUMO chains [4]. Curiously, this very high molecular weight species is only observed in neurons and not in recombinant cells when GISP is overexpressed together with SUMO-1 or SUMO-2. This may reflect the fact that GISP is a brain-specific protein and that it is handled differently when overexpressed in HEK293 or COS-7 cells, or may be due to differences in the regulation of the SUMOylation pathway between the cell types.

GISP was first identified as a protein that binds to the C-terminal domain of the GABAB1 subunit via a coiled-coil domain interaction which acts to regulate the forward trafficking of GABAB receptors [1]. In addition to GABAB receptor trafficking, GISP can also function as a neuron-specific regulator of membrane protein degradation via its interaction with TSG101, an integral component of the ESCRT machinery that functions in the sorting of membrane proteins for degradation in the lysosome [17,18]. GISP expression increases the steady-state levels of multiple receptor proteins in a manner that depends on its interaction with TSG101, suggesting an inhibitory action of GISP on the TSG101-mediated lysosomal sorting of membrane proteins [2,3].

Thus, the observation that GISP is a SUMO substrate opens the possibility that SUMOylation may play a role in the involvement of GISP in GABAB receptor trafficking or ESCRT-mediated degradation, however further work will be required to determine whether this is the case.

Our results suggest that GISP SUMOylation is responsive to neuronal activity. GISP, Ubc9 and SUMO-1 colocalise in neuronal processes, consistent with a potential role for these proteins in synaptic signalling. Colocalisation of GISP with SUMO-1 was enhanced upon stimulation of neurons with glycine to induce chem-LTP. Interestingly, this stimulation protocol also enhanced the colocalisation between Ubc9 and SUMO-1. These results are consistent with a number of other reports documenting activity-dependent changes in neuronal SUMOylation. For example, activation of SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells with potassium chloride leads to the Ca2+-sensitive enhancement of SUMOylation by all three SUMO paralogues [19]. Similarly, increases in global SUMOylation occurred in synaptosomes treated with potassium chloride and AMPA, while kainate treatment led to a decrease in global SUMOylation [20]. However, in each of these examples, the SUMO target proteins remain to be defined. Our data suggest that GISP may be one of these substrates.

A growing number of neuronal SUMO substrates have been described, implicating SUMOylation in numerous physiological and pathophysiological neuronal processes. Our data add to this body of evidence by identifying GISP as a novel SUMO substrate, potentially linking protein SUMOylation to GABAB receptor trafficking and the lysosomal degradation of membrane proteins. Further work will now be required to examine these possibilities.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the European Research Council, the MRC and the EU (GRIPPANT, PL 005320) for financial support. We thank Patrick Tidball for technical assistance.

References

- [1].Kantamneni S, Correa SA, Hodgkinson GK, Meyer G, Vinh NN, Henley JM, Nishimune A. GISP: a novel brain-specific protein that promotes surface expression and function of GABA(B) receptors. J. Neurochem. 2007;100:1003–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kantamneni S, Holman D, Wilkinson KA, Correa SA, Feligioni M, Ogden S, Fraser W, Nishimune A, Henley JM. GISP binding to TSG101 increases GABA receptor stability by down-regulating ESCRT-mediated lysosomal degradation. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kantamneni S, Holman D, Wilkinson KA, Nishimune A, Henley JM. GISP increases neurotransmitter receptor stability by down-regulating ESCRT-mediated lysosomal degradation. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;452:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Mechanisms, regulation and consequences of protein SUMOylation. Biochem. J. 2010;428:133–145. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rodriguez MS, Dargemont C, Hay RT. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12654–12659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sampson DA, Wang M, Matunis MJ. The small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) consensus sequence mediates Ubc9 binding and is essential for SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:21664–21669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xu J, He Y, Qiang B, Yuan J, Peng X, Pan XM. A novel method for high accuracy sumoylation site prediction from protein sequences. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Martin S, Nishimune A, Mellor JR, Henley JM. SUMOylation regulates kainate-receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Nature. 2007;447:321–325. doi: 10.1038/nature05736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nishimune A, Isaac JT, Molnar E, Noel J, Nash SR, Tagaya M, Collingridge GL, Nakanishi S, Henley JM. NSF binding to GluR2 regulates synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1998;21:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bouschet T, Martin S, Kanamarlapudi V, Mundell S, Henley JM. The calcium-sensing receptor changes cell shape via a beta-arrestin-1 ARNO ARF6 ELMO protein network. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2489–2497. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Analysis of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 as a potential substrate for SUMOylation. Neurosci. Lett. 2011;491:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wilkinson KA, Nishimune A, Henley JM. Analysis of SUMO-1 modification of neuronal proteins containing consensus SUMOylation motifs. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;436:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lu W, Man H, Ju W, Trimble WS, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2001;29:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Park M, Penick EC, Edwards JG, Kauer JA, Ehlers MD. Recycling endosomes supply AMPA receptors for LTP. Science. 2004;305:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1102026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Uchimura Y, Nakamura M, Sugasawa K, Nakao M, Saitoh H. Overproduction of eukaryotic SUMO-1- and SUMO-2-conjugated proteins in Escherichia coli. Anal. Biochem. 2004;331:204–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Anderson DB, Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Protein SUMOylation in neuropathological conditions. Drug News Perspect. 2009;22:255–265. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2009.22.5.1378636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Babst M. A protein’s final ESCRT. Traffic. 2005;6:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Williams RL, Urbe S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:355–368. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lu H, Liu B, You S, Xue Q, Zhang F, Cheng J, Yu B. The activity-dependent stimuli increase SUMO modification in SHSY5Y cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Feligioni M, Nishimune A, Henley JM. Protein SUMOylation modulates calcium influx and glutamate release from presynaptic terminals. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:1348–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]