Abstract

Background

Few population-based studies have examined the behavioral and psychosocial predictors of long-term weight-loss maintenance.

Purpose

The goal of this study was to determine the prevalence and predictors of weight-loss maintenance in a bi-racial cohort of younger adults.

Methods

This study examined a population-based sample of overweight/obese African-American and white men and women who had ≥ 5% weight loss between 1995 and 2000. Subsequent changes in weight, physical activity, and behavioral and psychosocial factors were examined between 2000 and 2005. Analyses were conducted in 2008–2009.

Results

Among the 1869 overweight/obese individuals without major disease in 1995, 536 (29%) lost ≥ 5% between 1995 and 2000. Among those that lost weight, 34% (n=180) maintained at least 75% of their weight loss between 2000 and 2005, whereas 66% subsequently regained. Higher odds of successful weight-loss maintenance were related to African-American race (OR = 1.7; p = .03), smoking (OR = 3.4; p = .0001), history of diabetes (OR= 2.2; p = .04), increases in moderate physical activity between 2000 and 2005 (OR = 1.4; p = .005), increases in emotional support over the same period (OR = 1.6; p = .01) and less sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption in 2005 (OR =0.8; p =.006).

Conclusions

One third of overweight men and women who lost weight were able to maintain ≥ 75% of their weight loss over 5 years. Interventions to promote weight-loss maintenance may benefit from targeting increased physical activity and emotional support and decreased sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption.

Introduction

Given the importance of obesity as a public health problem, it is surprising how little is known about the prevalence and predictors of long-term weight-loss maintenance. Weight-loss trials have shown that most patients regain weight after treatment termination,1 but the average individual who continues to participate in a clinical trial maintains a weight loss of about 3% of initial body weight for up to 5 years after treatment.2 Analyses examining predictors of treatment outcomes have identified some behaviors that appear to improve success, including continued consumption of a low-calorie, low-fat diet, increased physical activity, and self-monitoring.3–9 Psychosocial correlates of better weight-loss maintenance also have been recognized, including lower levels of depressive symptoms, stress, and disinhibition and higher levels of restraint and self-efficacy.8,10–16

Much of the clinical trial literature, however, has been limited by short-term follow-up (≤ 2 years), small sample sizes, high drop-out rates, and lack of intent-to-treat analyses. Moreover, clinical trials have generally evaluated specific short-term treatment approaches in individuals attending weekly weight-loss programs. Individuals who seek assistance for weight loss tend to be heavier,17 have more medical problems,18,19 and have higher percentages of binge eating20 than individuals in the general population. Since the individuals who attend clinical weight-loss treatments may be more difficult to treat, and clinical trials have generally evaluated specific short-term treatment methods (e.g., meal replacements, pharmacotherapy, very low–calorie diets),1 the results from such programs may not represent the true prevalence or typical methods for weight-loss maintenance in the general population. Moreover, although cohort studies of larger samples (n > 5,000) of successful weight losers exist (e.g., the National Weight Control Registry21), these data are based on self-selected samples, and include primarily women, whites, and educated individuals; thus, findings may not generalize to the population at large. Only a few empirical studies have attempted to estimate the prevalence of long-term weight-loss maintenance in the general U.S. population. Prevalence estimates of successful maintenance after weight loss have ranged from 58.9% in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES, 1999–2002),22 47% in a random-digit-dial survey,23 and 20% in the Nurses Health Study.7 Overall, these studies suggest that sustaining weight loss may be possible for a substantial subset of the general population. However, existing population-based studies have been based on self-reported weights and included a limited array of behavioral and psychosocial measures. Clearly, to better understand the prevalence and predictors of long-term weight control, further research is needed in both men and women that includes more diverse samples, measured weights, multiple follow-ups, and comprehensive assessments.

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study enrolled over 5000 African-American and white women and men, aged 18–30 years in 1985–1986, and has followed the cohort for over 20 years, recording serial measurements of weight and behavioral and psychosocial factors. Prior research in CARDIA has examined predictors of weight loss over 2 years of follow-up.24 Weight loss was generally associated with greater baseline fatness, lower baseline physical fitness level, self-perception of being overweight, dieting, and previous weight loss and regain. Other CARDIA papers have examined predictors of weight increases over time. In these studies, limited physical activity,25,26 greater fast-food consumption 27 and less dissatisfaction with body size 28 were identified as significant predictors of weight gain. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of successful weight loss and maintenance in the CARDIA cohort and to identify the strongest demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial predictors of 5-year weight-loss maintenance. It was hypothesized that among individuals who had lost ≥ 5% of their body weight, those with higher levels of physical activity, better dietary intake (e.g., fewer sugar-sweetened beverages, less fast-food consumption), and less depressive symptoms would be most likely to maintain at least 75% of their weight loss over 5 years of follow-up.

METHODS

Sample

CARDIA is a multicenter, longitudinal study of the development and determinants of cardiovascular disease over time among African-American and white adult men and women. The first CARDIA examination took place in 1985–1986 and included 5115 women and men. Sampling was designed to achieve balanced representation among white and African-American men and women, age (18–30 years), and education. Subsequent to baseline, the cohort was reexamined at Years 2, 5, 7, 10, 15 and 20 (spanning 1987–2005). All examinations were approved by IRBs at each institution. Details of the study design have been published elsewhere.29

To be included in the current study, participants had to have been overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25) and without self-reported major disease in 1995. Of the 3,950 participants who were assessed in 1995, a total of 2432 were overweight/obese; of these, 14 were eliminated due to pregnancy between 1995 and 2005 and 549 were eliminated due to a reported illnesses that could potentially have caused involuntary weight loss over the same time span, including one or more of the following: Kidney failure (n=14); cirrhosis (n=1); cancers (n=68); hyperthyroidism (n=32); digestive diseases (n=86); tuberculosis in past year (n=84); HIV (n=11); and/or any reported medical problems interfering with exercise (n=402; predominantly reflecting recent injuries, surgeries, or chronic pain). The remaining 1869 made up the final sample in this study. The weight loss of these 1869 participants was examined between 1995 and 2000 and then weight-loss maintenance between 2000 and 2005 (note that in the current study, calendar years [i.e., 2000, 2005] are used rather than CARDIA assessment years [i.e., Year 15, Year 20] to refer to study time points).

Overall retention for the 1995, 2000 and 2005 examinations was 78.5%, 74%, and 72% of surviving participants, respectively (approximately 2.5% were deceased as of the 2000 examination and 3.4% in 2005).30,31 Whites, nonsmokers, more educated participants, and slightly older participants were more likely to return for these exams than African Americans, smokers, those with less education, and younger participants.32 There was no significant relationship with BMI and exam retention.

Measures

As the main purpose of this study was to examine variables associated with weight-loss maintenance versus regain, assessments occurred after participants’ initial weight loss (between 1995 and 2000) at the 2000 and 2005 examinations. Some variables (anger and coping) were assessed in the 2000 exam only, and others (i.e., diet history) in the 2005 examination only, as indicated in the sections that follow.

Outcome definitions

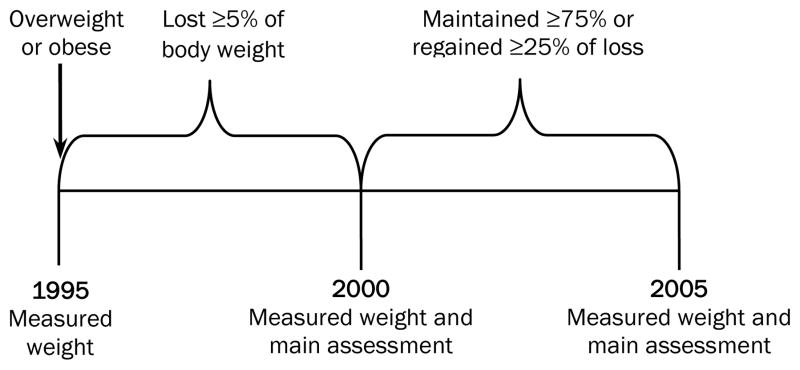

Weight-loss maintainers were defined as participants who were overweight or obese in 1995 (and without pregnancy or major medical illnesses affecting weight), had lost ≥ 5% by 2000, and had maintained 75% of their weight loss by 2005. A 5% weight-loss criterion was chosen, as this has been shown in numerous studies to be associated with substantial health benefits 33 and has been recommended by the IOM as the weight-loss criterion for evaluating success of weight-loss programs;34 this criterion has also been used in other epidemiologic research examining weight-loss maintenance.7 Although successful weight control can involve some weight regain, successful weight loss was further defined as maintaining ≥ 75% of the weight loss for 5 years to identify a relatively weight stable group of weight-loss maintainers.13,35 Regainers were defined as individuals who were overweight or obese in 1995 (and without pregnancy or major medical illnesses affecting weight), had lost ≥ 5% by 2000, but had regained > 25% of their weight loss by 2005 (Figure 1). Note that the terms “weight-loss maintainer” and “regainer” are used to denote these groups, but intentionality of weight changes should not be inferred by the use of these terms.

Figure 1.

Scheme for assessing weight loss maintenance in overweight or obese participants who had lost ≥ 5% of their body weight between 1995 and 2000, and maintained ≥ 75% of the weight loss between 2000 and 2005. Weight regain was defined as regaining >25% of weight loss. All participants were without self-reported major disease or pregnancy in 1995.

Weight, height, demographics

Weight and height were measured in light clothing and without shoes at the 1995, 2000, and 2005 examinations using calibrated equipment. BMI was calculated by standard formula. Demographic and medical information collected at the 2000 and 2005 examinations were used in analyses. At these time points, all participants were interviewed by trained personnel about their medical history and current use of cigarettes and alcoholic beverages. In 2005, participants were also asked whether they had ever had bariatric surgery. Voluntary versus involuntary weight loss and weight cycling between assessment points was not directly assessed.

Leisure time physical activity

The CARDIA physical activity questionnaire36 was administered in both 2000 and 2005. Total physical activity was expressed in exercise units as a product of intensity x frequency x 100, to yield a total activity score.

Dietary intake

Diet variables were selected based on previous research in weight-loss maintenance21,37 and included calorie intake, percentage of calories from fat, and fast- food and soft drink consumption using a diet history questionnaire administered in 2005.31,38,39 Fast-food habits were assessed in 2000 and 2005.31

Psychosocial measures

Depressive symptomatology was assessed in both 2000 and 2005 using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES-D).40 The shortened version of the SF-36 was used to assess quality of life in the 2000 and 2005 examinations.41 Social network was measured in 2000 and 2005.42 Social support was also measured in 2000 and 2005 using 8 items drawn from the MacArthur Network.43 Anger was assessed in 2000 only, using the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2.44,45 Coping was assessed in 2000 only, using the Reactive Responding Measure.46 Sleep disturbances were assessed in 2000 and 2005 using questions from the Sleep Heart Health Study 47 pertaining to excessive daytime sleepiness, trouble falling asleep, and frequent awakening.

Statistics

SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Initial univariate t-tests and chi-square analyses were conducted to compare groups on demographic and weight-related characteristics. Participants with missing weight data in the final assessment point (2000; n = 85) were classified as weight regainers to provide a conservative estimate of the prevalence of successful weight-loss maintenance, but analyses that excluded these 85 individuals revealed similar findings. A three-step process was used to identify the most robust set of predictors of weight-loss maintenance versus weight regain. First, initial multivariate ANOVA for repeated measures was used to examine changes over time (between 2000 and 2005) in each variable and interactions with group (Maintainer versus Regainer), both with and without adjusting for demographic variables affecting weight (race, smoking status, age, gender, marital status, dieting history, 1995 BMI, and percentage weight loss since 1995; Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean behavioral and psychological characteristics at the 2000 and 2005 follow-up examinations

| Characteristic | 2000 Examination | p | 2005 Examination | Significance | Group x time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maintainers | Regainers | Maintainers | Regainers | Group | Time | |||

| % current smoker | 33.2 | 23.0 | .0001 | 23.6 | 15.8 | .0005 | .006 | .05 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Total | 345.0 ± 22.1 | 382.4 ± 16.7 | .07 | 344.3 ± 22.4 | 327.9 ± 19.3 | ns | ns | ns |

| High | 203.2 ± 16.9 | 238.4 ± 12.8 | .10 | 199.1 ± 17.2 | 205.8 ± 14.8 | ns | ns | .ns |

| Moderate | 141.8 ± 8.4 | 143.9 ± 6.3 | .14 | 145.2 ± 8.5 | 122.1 ± 7.3 | ns | ns | .08 |

| Sleep | ||||||||

| % daytime sleepiness | 25% | 24% | ns | 30% | 31% | ns | .04 | ns |

| % trouble falling asleep | 23% | 19% | ns | 25% | 21% | ns | ns | ns |

| % frequent awakenings | 46% | 53% | .07 | 48% | 57% | .02 | ns | ns |

| Psychosocial | ||||||||

| Quality of life: Physical component | 51.7 ± 0.5 | 52.3 ± 0.4 | ns | 50.3 ± 0.5 | 49.9 ± 0.5 | ns | .0001 | ns |

| Quality of life: Mental component | 49.8 ± 0.7 | 50.1 ± 0.5 | ns | 50.9 ± 0.7 | 51.1 ± 0.5 | ns | .05 | ns |

| Chronic Burden | 1.9 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.03 | ns | 1.7 ± 0.05 | 1.7 ± 0.04 | ns | .0001 | ns |

| Social support: Positive Emotional | 2.1 ± 0.05 | 2.1 ± 0.04 | ns | 2.0 ± 0.05 | 2.1 ± 0.04 | ns | .ns | .10 |

| Social support: Negative Emotional | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.03 | ns | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.04 | ns | ns | ns |

| Social Network | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | ns | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | .13 | .0001 | ns |

| CES-D (Total) | 10.0 ± 0.6 | 10.0 ± 0.4 | ns | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | ns | ns | .ns |

| Anger out | 1.8 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.02 | ns | — | — | .14 | — | — |

| Reactive responding: Emotional | 2.9 ± 0.06 | 2.9 ± 0.04 | ns | — | — | ns | — | — |

| Reactive responding: Goal | 3.7 ±0.06 | 3.8 ± 0.04 | ns | — | — | .13 | — | — |

| Reactive responding: Vigilance | 2.8 ± 0.05 | 2.8 ± 0.04 | ns | — | ns | — | ||

| Diet | ||||||||

| Total calories/d | — | — | — | 2384 ± 110.3 | 2580 ± 101.3 | ns | — | — |

| % kcal from fat/d | — | — | — | 36.6 ± 0.70 | 36.0 ± 0.6 | ns | — | — |

| % kcal from CHO/d | — | — | — | 45.1 ± 0.81 | 46.8 ± 0.70 | .10 | — | — |

| % kcal from protein/d | — | — | — | 16.1 ± 0.30 | 15.3 ± 0.30 | .08 | — | — |

| Sugar-sweetened drinks (srv/d) | — | — | — | 0.93 ± 0.13 | 1.2 ± 1.7 | .02 | — | — |

| Diet beverages (srv/d) | — | — | — | 1.4 ± 0.20 | 0.99 ± 0.18 | .08 | — | — |

| Water (srv/d) | — | — | — | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | ns | — | — |

| Alcohol (srv/week) | 7.7 ± 0.9 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | .09 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | ns | ns | ns |

| Fast food (srv/week) | 3.4 ± 0.04 | 3.3 ± 0.03 | Ns | 3.5 ± 0.04 | 3.4 ± 0.04 | .07 | .14 | ns |

Unadjusted values are presented for ease in interpretation; p-values reflect analyses with adjustment for race, smoking status, age, gender, marital status, dieting history, and initial BMI and weight loss.

p-values < 0.15 are displayed in the table and denote variables that were entered into subsequent models.

ns = nonsignificant (p > .15); srv/d= servings per day; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale; CHO = carbohydrate

Second, variables that were found to be significant or approached significance (p <.15; see Table 2) in these initial adjusted models were entered into a stepwise analysis within predefined categories (i.e., demographic, smoking, physical activity, macronutrient [% of calories from carbohydrate, protein], dietary components [fast food, diet soft drink, sugar-sweetened soft drinks] psychosocial, and sleep). Third, variables that were significant (p < .05) within each predefined category in the stepwise analyses were individually added to a sequential hierarchic model to see whether its inclusion improved the fit of the model using a significant likelihood ratio chi-square. The sequential order in the hierarchic model was based on previous research on variables affecting weight-loss maintenance 21,37 and was as follows: (1) demographic and smoking; (2) physical activity; (3) diet (either macronutrient or specific dietary components, such as fast food or soft drinks; each was analyzed in separate models); (4) psychosocial variables; and, (5) sleep variables.

A sensitivity analysis was also conducted using an inverse weighting probability model in which the presence and absence in the final analysis was included as a dependent variable. However, accounting for missingness as an independent variable in the final model did not appreciably influence the findings; thus, only results from the completers’ analyses are presented here.

RESULTS

Participants were 1869 non-pregnant overweight/obese individuals without major disease in 1995. They were, on average, aged 40.1 ±3.7 years with 47% female, 39% white; 48% married, and 69% with a high school education or more. Of these 1869, a total of 536 (29%) lost at least 5% of their body weight between examinations in 1995 and 2000; of these 180 (33.5%) maintained at least 75% of their weight loss between 2000 and 2005, and were classified as “weight-loss maintainers;” 356 (66.4%) had lost ≥5% but regained more than 25% of their weight loss during 2000–2005 and were classified as “weight regainers.” The maintainers and regainers were compared (below) to identify the characteristics in year 2000 that best distinguished these two groups.

Baseline (year 2000) and changes from 1995 to 2000 as predictors of subsequent regain Demographic characteristics and weight changes

Maintainers and regainers differed on a number of weight-related characteristics (Table 1). Moreover, a significantly greater proportion of weight-loss maintainers than regainers self-reported a history of diabetes (7.5% vs 4.7%, respectively; p = .001) but no significant differences were observed in reported history of high blood pressure (28% vs 21%, respectively; p = .19).

Table 1.

Comparison of those who maintained their weight loss and those who regained between 2000 and 2005 on demographic and weight-related variables in 2000.

| Weight-loss Maintainer n = 180 | Weight Regainer n = 356 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years) | 40.1 ± 3.7 | 39.7 ±3.6 | .18 |

| % Female | 47.5 | 46.0 | .75 |

| % White | 36.3 | 41.7 | .22 |

| % African-American | 63.7 | 58.2 | |

| % Married | 47.2 | 48.2 | .84 |

| % High school educated or more | 67.5 | 70.7 | .44 |

| Weight/weight-loss information in 1995 and 2000 | |||

| Weight (kg) in 1995 | 103.9 ± 24.2 | 100.4 ± 19.8 | .08 |

| BMI in 1995 | 35.4 ± 7.8 | 34.0 ± 6.2 | .02 |

| Weight (kg) at year 2000 | 92.3 ± 19.0 | 90.6 ± 17.3 | .29 |

| BMI at year 2000 | 31.5 ± 6.0 | 30.7 ± 5.3 | .10 |

| Weight loss (1995 wt [kg] – 2000 wt [kg]) | 11.6 ± 9.0 | 9.9 ± 6.0 | .007 |

| Percentage weight loss ([1995 wt – 2000 wt]/1995 wt) | 10.6 ± 5.7 | 9.6 ± 4.5 | .04 |

Weight regain = lost ≥ 5% between 1995 and 2000 and regained >5% between 2000 and 2005. Weight-loss maintenance = lost ≥5% between 1995 and 2000 and maintained ≥ 75% of that weight loss between 2000 and 2005. Weight and height in 1995, 2000, and 2005 were based on measured weights using calibrated equipment.

Behavioral and psychosocial characteristics at year 2000

In general, the behavioral and psychosocial characteristics measured in the 2000 examination did not differ between those who subsequently gained or maintained their weight 5 years later (Table 2). However, a significantly greater proportion of weight-loss maintainers than regainers reported smoking in the 2000 examination (33% vs 23%, respectively, p =.0001). Moreover, there was a trend for greater alcohol consumption in maintainers than regainers (7.4 vs 6.6 drinks/week; p = .09; Table 2). Additionally, there were trends for maintainers to report engaging in slightly less physical activity initially and to report less prevalent awakenings at night (Table 2).

Change between the 2000 and 2005 examinations

Additional analyses compared changes between the 2000 and 2005 examinations for those who regained weight versus those who maintained their previous weight loss. During this time span, weight-loss maintainers continued to lose weight (4 kg loss) and further reduced their BMI from 31.5 ± 6.0 to 30.4 ± 6.5 kg/m2 while regainers increased to above baseline (8.8 kg gain) from a BMI of 30.7 ± 5.3 to 33.6 ± 6.4 kg/m2. In 2005, maintainers were lighter than regainers (88.5 ± 18.7 vs 99.3 ± 20.5 kg; p = .0001) and were maintaining a weight loss of approximately 15% from 1995 compared with 1% weight regain above baseline for regainers.

Examining variables assessed in both the 2000 and 2005 examinations, there was a significantly greater reduction in smoking prevalence among regainers than maintainers (p = .05); Table 2). There was also a trend (p <0.08) for maintainers to slightly increase their physical activity while regainers decreased their activity. Group main effects were also found for sleep (Table 2). Examining psychosocial characteristics, several time effects were observed, including substantial declines in physical and mental quality of life scores (Table 2), but the maintainers and regainers had similar changes.

Table 2 also shows results of the diet history questionnaire administered in 2005. Maintainers consumed significantly (p =.02) fewer daily servings of sugar-sweetened soft drinks than regainers and slightly more diet soft drinks, fewer calories from protein, and more fast food, but these latter trends were not significant. History of bariatric surgery was also assessed in 2005; 4 maintainers and no regainers reported ever having had bariatric surgery.

Multivariable analyses

In models containing all variables that were significant or approached significance in univariate analyses, significant predictors of the odds of maintaining weight versus being a regainer included African-American race, history of diabetes, and current smoking at years 2000 and 2005, as well as increases in moderate physical activity between 2000 and 2005, increases in emotional support during the same time span, and less sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption in 2005 (Table 3). In analyses that included macronutrients (instead of foods) as the dietary block, similar findings were observed for changes in moderate activity (OR=1.3 [1.1, 1.6] p=.007) and emotional support (OR=1.6 [1.1, 2.3]; p=.01); however, intake of macronutrients was not a significant predictor. Analyses excluding the 4 participants who reported a history of bariatric surgery revealed near identical findings.

Table 3.

Odds of being in the weight-loss maintainers versus regain category

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| African-American | 1.7 | 1.1, 3.0 | .03 |

| Female | 0.9 | 0.5, 1.4 | ns |

| Married (Nonmarried = ref) | 0.9 | 0.6, 1.6 | ns |

| BMI (year 1995) | 0.9 | 0.9, 1.0 | ns |

| Weight loss between 1995 and 2000 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.0 | ns |

| Smoker in 2000 and 2005 (Never-smokers=ref) | 3.4 | 1.9, 6.2 | .0001 |

| Dieting history | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.0 | ns |

| History of diabetes | 2.2 | 1.0, 5.1 | .04 |

| Increase in units of moderate activity (2000–2005) | 1.4 | 1.1, 1.7 | .005 |

| Soft drink consumption (servings/day; year 2005) | 0.8 | 0.7, .9 | .006 |

| Increases in emotional support (2000–2005) | 1.6 | 1.2, 2.7 | .01 |

Race, gender, marital status, dieting history, and history of diabetes, measured in 2000. Results based on sequential multiple regression in which demographic variables were entered first, followed by physical activity, dietary, and psychosocial variables. ns = nonsignificant (p > .05)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study was the first to examine the prevalence of weight loss and maintenance in a diverse population-based cohort using prospectively measured weights. The first principal finding was that 29% (536 of 1869) of the overweight and obese population successfully lost a modest amount of weight (≥5%) over a 5-year time span, with only four of these 536 participants having reported bariatric surgery. In a similarly aged population of women, the Nurses Health Study found that fewer (13%) overweight and obese women had successfully lost ≥5% of their body weight over a 2-year period (determined using self-reported weights). While encouraging that nearly one third of overweight and obese individuals were successful at weight loss, more effective strategies may be needed to increase the proportion of overweight and obese individuals in the population who lose weight.

Although it is commonly believed, based on clinical trial outcomes, that very few individuals succeed at long-term weight-loss maintenance,48,49 34% of the overweight individuals who had successfully lost weight in CARDIA were able to keep the weight off over 5 years. Using similar criteria but self-reported weights, the Nurses Health Study 7 found that approximately 20% of those who had lost ≥ 5% kept it off over 2 years. In NHANES (1999–2002), 58.9% of participants reported keeping ≥10% weight loss off (within 5%) for 1 year, also based on self-reported weight. The prevalence of both successful weight loss and maintenance among overweight individuals was 10% in the current study, 15% in the Nurses Health study, and 18% in a random-digit-dial survey.23 As CARDIA is the only study that used measured weights, its estimates are potentially the most accurate. However, differences in the definitions used may also explain differences in the estimated prevalence. Nonetheless, these data and other national 8,50 and international 51 reports similarly suggest that successful weight-loss maintenance, although infrequent, may be more prevalent in the general population than commonly assumed. Surprisingly, no significant differences were found in the prevalence of successful weight loss and maintenance across age and gender. In contrast, African Americans had higher odds of long-term weight-loss maintenance than whites. Another population-based study similarly found greater percentages of self-reported successful weight-loss maintenance in African Americans than whites.8 However, the NHANES study found no significant differences in prevalence between African Americans and whites, and lower prevalence in Mexican Americans.22 Some clinical weight-loss trials have shown minorities to be somewhat less successful than nonminorities at weight loss 52,53 but as successful 54 or more successful 55 at weight-loss maintenance. Findings from the current cohort study, which may be more generalizable than clinical trial data, suggest that long-term weight-loss maintenance is similar in men and women and better in African-American than white populations.

Examining predictors and correlates of weight-loss maintenance, physical activity emerged as a significant variable, a finding that is consistent with findings from both clinical trial 58 and epidemiologic 7 studies. Lower sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption was also related to higher odds of successful weight-loss maintenance. Evidence is mixed on the role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the promotion of weight gain and obesity.59–65 A recent study that compared successful weight losers and normal weight controls indicated that weight-loss maintainers consumed little in the way of sugar-sweetened beverages.66 The current study’s findings are consistent with these latter data, and further suggest that limiting intake of sugar-sweetened beverages is characteristic of long-term successful weight losers.

The study has some limitations. Even though, to be conservative, individuals were excluded who had diseases that could promote unintentional weight loss or inhibit physical activity, intentionality of weight loss was not directly assessed in 2000 and, thus, prevalence estimates of successful weight control could be inflated. Studies that have assessed and excluded unintentional weight losers have reported similar prevalences as those in the current study.22,71 Nonetheless, the extent to which successful weight losers in this study represent intentional versus unintentional weight losers remains unclear, so these results should be interpreted with caution. This is an observational study, so causality cannot be inferred. Moreover, while population-based, this study was conducted with participants who have remained in CARDIA through 20 years of follow-up and who may differ in their motivation and/or weight change patterns than the population at large. Finally, the assessments done in this study, while comprehensive, were not all administered at every examination and not every factor known or thought to be associated with successful weight control was measured (e.g., dietary restraint, disinhibition, self-efficacy, environmental factors). Also, since the measures were collected 5 years apart, the extent to which weight cycled in the interim years was unknown.

In summary, 29% of overweight and obese men and women successfully lost ≥ 5% of their body weight over a 5-year time span, and 34% of those who lost weight were able to maintain their weight losses over the next 5 years; African Americans were more likely than whites to be classified as a weight-loss maintainer. Public health interventions to promote weight-loss maintenance may benefit from targeting increased physical activity and emotional support, and decreased soft drink consumption.

Acknowledgments

Work on this manuscript was supported (or partially supported) by contracts: University of Alabama at Birmingham, Coordinating Center, N01-HC-95095; University of Alabama at Birmingham, Field Center, N01-HC-48047; University of Minnesota, Field Center and Diet Reading Center (Year 20 Exam), N01-HC-48048; Northwestern University, Field Center, N01-HC-48049; and, Kaiser Foundation Research Institute, N01-HC-48050 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. NHLBI had input into the overall design and conduct of the CARDIA study. The NHLBI co-author, Dr. Loria, was involved in all stages of the current study, including study concept and design, analysis, interpretation, and write-up. The authors have no other potential conflict of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007 Oct;107(10):1755–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of U.S. studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001 Nov;74(5):579–584. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanWormer JJ, Martinez AM, Martinson BC, et al. Self-weighing promotes weight loss for obese adults. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Jan;36(1):70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing R. Physical activity in the treatment of the adulthood overweight and obesity: Current evidence and research issues. Med Science Sports Exer. 1999;31(11):S547–S552. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perri MG. The maintenance of treatment effects in the long-term management of obesity. Clin Psychol Scientific Pract. 1998;5:526–543. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Bray G, Bouchard C, James P, editors. Handbook of Obesity. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1998. pp. 855–873. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field AE, Wing RR, Manson JE, Spiegelman DL, Willett WC. Relationship of a large weight loss to long-term weight change among young and middle-aged U.S. women. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1113–1121. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruger J, Blanck HM, Gillespie C. Dietary practices, dining out behavior, and physical activity correlates of weight loss maintenance. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008 Jan;5(1):A11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jul 28;168(14):1550–1559. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. discussion 1559–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrne SM, Cooper Z, Fiarburn CG. Psychological predictors of weight regain in obesity. Behav Res Therapy. 2004;42:1341–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edell BH, Edington S, Herd B, O’Brien RM, Witkin G. Self-efficacy and self-motivation as predictors of weight loss. Addict Behav. 1987;12:63–66. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster JL, Jeffery RW. Gender differences related to weight history, eating patterns, efficacy expectations, self-esteem, and weight loss among participants in a weight reduction program. Addict Behav. 1986;11:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Lang W, Hill JO. What predicts weight regain among a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:177–185. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Rissanen A, Kaprio J. A descriptive study of weight loss maintenance: 6 and 15 year follow-up of initially overweight adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:116–125. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Coutinho SR, et al. Mediators of weight loss and weight loss maintenance in middle-aged women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(4):725–735. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butryn ML, Thomas JG, Lowe MR. Reductions in internal disinhibition during weight loss predict better weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 May;17(5):1101–1103. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy AS, Heaton AW. Weight control practices of U.S. adults trying to lose weight. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 part 2):661–666. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffery RW, Adlis SA, Forster JL. Prevalence of dieting among working men and women: the healthy worker project. Health Psychol. 1991;10(4):274–281. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.4.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeffery RW, Folsom AR, Luepker RV, et al. Prevalence of overweight and weight loss behavior in a metropolitan adult population: the Minnesota Heart Survey experience. Am J Public Health. 1984 Apr;74(4):349–352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce B, Wilfley D. Binge eating among the overweight population: a serious and prevalent problem. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996 Jan;96(1):58–61. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jul;82(1 Suppl):222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Kettel Khan L, Gillespie C, Serdula MK. Weight regain in U.S. adults who experienced substantial weight loss, 1999–2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Hill JO. Behavioral strategies of individuals who have maintained long-term weight losses. Obes Res. 1999;7(4):334–341. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bild DE, Sholinksy P, Smith DE, Lewis CE, Hardin JM, Burke GL. Correlates and predictors of weight loss in young adults: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes. 1996;20:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis C, Smith D, Wallace D, Williams OD, Bild D, Jacobs DR. Seven-year trends in body weight and associations with lifestyle and behavioral characteristics in black and white young adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Publ Health. 1997;87(4):635–642. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon-Larsen P, Hou N, Sidney S, et al. Fifteen-year longitudinal trends in walking patterns and their impact on weight change. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;89(1):19–26. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereira MA, Kartashov AB, Ebbeline CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch E, Liu K, Wei GS, Spring B, Kiefe C, Greenland P. The Relation Between Body Size Perception and Change in Body Mass Index Over 13 Years: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 Feb 16; doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes GH, Cutter G, Donahue R, et al. Recruitment in the Coronary Artery Disease Risk Development in Young Adults (Cardia) Study. Control Clin Trials. 1987 Dec;8(4 Suppl):68S–73S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pletcher MJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Lewis CE, et al. Prehypertension during young adulthood and coronary calcium later in life. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jul 15;149(2):91–99. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;367(9453):36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis C. Predictors of weight outcomes, dietary behaviors, and physical activity in coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA). Paper presented at: Predictors of Obesity, Weight Gain, Diet and Physical Activity Workshop; 2004; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leiva D. What are the benefits of moderate weight loss? Exper Clin Endocrin Diab. 1998;106(Suppl 2):10–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1212030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.IOM. Criteria for evaluating weight-management programs. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1995. Weighing the options. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelan S, Hill JO, Lang W, DiBello JR, Wing RR. Recovery from relapse among successful weight losers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1079–1084. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs DR, Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and reliability of short physical activity history: CARDIA and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. J Cardiopul Rehab. 1989;9:448–459. doi: 10.1097/00008483-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wing RR, Papandonatos G, Fava JL, et al. Maintaining large weight losses: the role of behavioral and psychological factors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008 Dec;76(6):1015–1021. doi: 10.1037/a0014159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald A, Van Horn L, Slattery ML. The CARDIA dietary history: development, implementation, and evaluation. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91:1104–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu K, Slattery M, Jacobs D, et al. A study of the reliability and comparative validity of the cardia dietary history. Eth Disease. 1994;4(1):15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depressive scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) I: Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonsson D, Rosengren A, Doteval A, Lappas G, Wilhelmsen L. Job control, job demands and social support at work in relation to cardiovascular risk factors in MONICA 1995, Goteborg. J Cardiovas Risk. 1999;6(6):379–385. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychol. 2001 Jul;20(4):243–255. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory -2. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resource Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spielberger CD, Reheiser EC, Sydeman SJ. Measuring the Experience, Expression, and Control of Anger. In: Kassinove H, editor. Anger Disorders: Definition, Diagnosis, and Treatment. 1995. pp. 49–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Psychosocial resources and the SES Health Relationship. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;893:210–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quan SF, Howard BV, Iber C, et al. The Sleep Heart Health Study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep. 1997 Dec;20(12):1077–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stunkard AJ. The management of obesity. NY State J Med. 1958;58:79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew AM, Samuels B, Chatman J. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol. 2007 Apr;62(3):220–233. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phelan S, Wing RR. Prevalence of successful weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Nov 14;165(20):2430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.20.2430-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Zwaan M, Hilbert A, Herpertz S, et al. Weight loss maintenance in a population-based sample of German adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Nov;16(11):2535–2540. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stevens VJ, Hebert PR, Whelton PK. Weight-loss experience of black and white participants in NHLBI-sponsored clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1631S–1638S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1631S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hollis JF, Gullion CM, Stevens VJ, et al. Weight loss during the intensive intervention phase of the weight-loss maintenance trial. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Aug;35(2):118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Mar 12;299(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004 Sep;12(9):1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gorin AA, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Medical triggers are associated with better short- and long-term weight loss outcomes. Prev Med. 2004 Sep;39(3):612–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norris SL, Zhang X, Avenell A, et al. Long-term effectiveness of lifestyle and behavioral weight loss interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2004 Nov 15;117(10):762–774. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wing RR. Physical activity in the treatment of the adulthood overweight and obesity: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999 Nov;31(11 Suppl):S547–552. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Aug;84(2):274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007 Apr;97(4):667–675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American Institute for Cancer Research., World Cancer Research Fund. Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective: a project of World Cancer Research Fund International. Washington, D.C: American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pereira MA. The possible roel of sugar-sweetened beverages in obesity etiology: A review of the evidence. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(Suppl 3):S28–S36. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bachman CM, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA. Is there an association between sweetened beverages and adiposity? Nutr Rev. 2006 Apr;64(4):153–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forshee RA, Anderson PA, Storey ML. Sugar-sweetened beverages and body mass index in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Jun;87(6):1662–1671. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibson S. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence from observational studies and interventions. Nutr Res Rev. 2008 Dec;21(2):134–147. doi: 10.1017/S0954422408110976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phelan S, Lang W, Jordan D, Wing RR. Use of artificial sweeteners and fat-modified foods in weight loss maintainers and always-normal weight individuals. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009 Jul 28; doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Black DR, Gleser LJ, Kooyers KJ. A meta-analytic evaluation of couples weight-loss programs. Health Psychol. 1990;9:330–347. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wing R, Jeffery R. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(1):132–138. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brownell KD, Stunkard AJ. Couples training, pharmacotherapy, and behavior therapy in the treatment of obesity. Arch Gen Psych. 1981;38:1224–1228. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780360040003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wing RR, Marcus MD, Epstein LH, Jawad A. A “Family-Based” Approach to the Treatment of Obese Type II Diabetic Patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(1):156–162. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McGuire M, Wing R, Hill J. The prevalence of weight loss maintenance among American adults. Int J Obes. 1999;23:1314–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]