Dubbed the ‘Nicholson Challenge’ by Health Select Committee chair, Stephen Dorrell, the NHS must save £20 billion by 2015, or four per cent per year. Monitor, the independent Foundation Trust (FT) regulator, has more recently indicated that this is more likely to be six per cent per year. However, hospital productivity is falling and primary care trusts are failing to meet savings targets. David Cameron has said: ‘It's not that we can't afford to modernize; it's that we can't afford not to modernize’.1

Despite preoccupation with the reform agenda, the most pressing issue facing the NHS is the need to increase value: maintaining and improving the quality of care whilst saving money. To achieve this, engagement of clinicians is essential. We therefore cannot afford not to involve the junior doctor community. This article examines why junior doctors are essential for the NHS to achieve efficiency savings, why they are currently disengaged from the process and potential initiatives to address this.

Why engage junior doctors in NHS leadership?

Medical engagement is where doctors actively and positively contribute towards enhancing the performance of the organization in which they work. NHS hospitals with enhanced medical engagement perform better2 and those with more structured medical leadership initiatives have improved rates of hospital acquired infection, staff productivity and financial performance.3

Disengagement of doctors can have disastrous consequences as highlighted at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells, and Mid Staffordshire NHS Trusts. Successful implementation of quality and cost improvement initiatives in the NHS have been previously, in part, determined by the extent of doctors' engagement.

Sir Bruce Keogh, NHS medical director, has long championed junior doctors as an untapped resource to improve the NHS:

‘Junior doctors who work closely with patients and alongside other members of staff on the shop floor 24 hours a day have penetrating insight into how things really work – where the frustrations and inefficiencies lie, where the safety threats lurk and how quality of clinical care can be improved.’4

Nearly three-quarters of hospitals have no senior acute medical cover at weekends5 and medical trainees often make clinical decisions that should be made by senior colleagues.6 Failure to engage a component of the workforce responsible for so much clinical activity will obstruct the NHS from achieving significant savings.

Why junior doctors may be disengaged

The clinical-managerial divide

General management was introduced to the NHS following the Griffiths report in 1983. The internal market in the early 1990s encouraged the healthcare system to adopt more corporate behaviours and was strengthened through a variety of policies under New Labour. This ‘managerialization’ of medicine has demoralized doctors and disengaged them from healthcare management, creating a ‘divide’ between clinicians and managers.7

Workload

Over the last 15 years, the New Deal and European Working Time Directive has reduced the working hours of NHS junior doctors without decreasing their workload. Currently, a single junior doctor may have primary responsibility for up to 400 patients at night. An apparent rise in sick leave has placed further demand on those covering rota gaps. To ensure junior doctors are adequately trained within reduced working hours, they are now also responsible for organizing regular, formal, work-based placed assessments of their skills. This may have, perversely, increased workload. Many royal colleges also require membership exams to be completed earlier in training. The net outcome is that junior doctors are under increasing pressure to manage their clinical responsibilities rather than engage with non-clinical managerial activities.

Low morale

Traditionally, doctors worked in ‘firms’, providing continuity for patients and team members. Reduced working hours mean hospital juniors often work with different colleagues on a daily basis, preventing the development of team camaraderie. In addition, shorter, more frequent and irregular shift patterns may have paradoxically worsened quality of life. Throughout the NHS, junior doctors are now recruited to jobs via central nationalized programs, which can make applicants feel de-humanized. This was particularly evident during the Medical Training Application Service debacle. A once guaranteed ‘job for life’, junior doctors now face unfavourable job competition ratios, leaving many feeling uncertain about their future. Modernizing Medical Careers (MMC) has introduced competency-based curricula, which have been criticised as box-ticking exercises. Publically recognized job titles such as ‘House Officer’ and ‘Senior House Officer’ have been banished, with potentially de-professionalizing consequences.

Lack of organizational allegiance

Nowadays, doctors activities are often driven by external processes and targets, over which they have little personal investment or ownership.8 Junior doctors' contracts are rarely held by the organizations in which they work and their induction into the NHS is generally poor, both of which may perpetuate a feeling of isolation. Furthermore, junior doctor jobs that used to be six months duration are now much shorter; along with the loss of free hospital accommodation, this reduces the opportunity to build loyalty to their Trust.

Clinical leadership initiatives in the NHS

The literature identifies four main ways to encourage clinical leadership:9–12 training, development and support; career structures; appropriate incentives; and information systems.

Training, development and support

Despite leadership being a key responsibility for doctors, formal training is notably absent from undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, leaving many senior medical managers feeling under-prepared.13 Currently, the majority of training manifests as ineffective short courses or formal qualifications, such as master's degrees that doctors must often complete in their own time. Established in 1990, the British Association of Medical Managers (BAMM) provided professional identity and support for doctors in management roles. It also recognized the importance of the next generation and had a highly active junior division. Despite ceasing operations in 2010, BAMM's contribution supported the development of the Medical Leadership Competency Framework (MLCF).14 This outlines leadership competencies in five domains that all doctors should achieve to become more actively involved in the planning, delivery and transformation of health services (Figure 1). The framework has been supported and adopted by all postgraduate medical royal colleges and incorporated into their curricula. Expedited by the cessation of BAMM, the Academy of Royal Colleges have established a Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management (FMLM) that ‘aims to promote the advancement of medical leadership, management and quality improvement at all stages of the medical career for the benefit of patients’ (www.fmlm.ac.uk/about-us). This is a step towards medical management becoming a specialty with professionally recognised accreditation.

Figure 1.

Medical Leadership Competency Framework (reproduced from (1))14

In the US, dual medical and management degrees are increasingly popular, which UK medical schools could consider. However, the next generation of NHS doctors may favour more informal mentoring, coaching and networking. In London, Prepare to Lead provides mentorship for junior medical leaders. A Buddy Scheme has also been developed in the North West of England, which pairs trainee managers and doctors to learn from each other and encourage clinical engagement from an early stage.15 Organizations such as The Network (www.the-network.org.uk) and the North Western Medical Leadership School formalize opportunities for like-minded medics interested in clinical leadership to provide support, opportunities and ideas.

Career structures

Doctors' involvement in NHS management is not new. Following the Griffiths report, most hospitals organized themselves into clinical directorates based on pioneering work at Guy's Hospital. Since 1991 it has been mandatory for hospital boards to have medical directors. The directorate model was implemented with variable success and actively undermined by some doctors. Whilst non-medical managers have largely expressed satisfaction with this system, clinical directors have been less positive,16 perhaps due to a perceived lack of training.

In primary care, total purchasing pilots and, more recently, practice-based commissioning (PBC) have delegated budgetary responsibility to GPs from health authorities and primary care trusts respectively. Despite making only modest improvements in healthcare services, they have improved engagement of GPs in management.17 The current reforms could develop this further, however, most organizations representing doctors, managers and patients remain cautious.

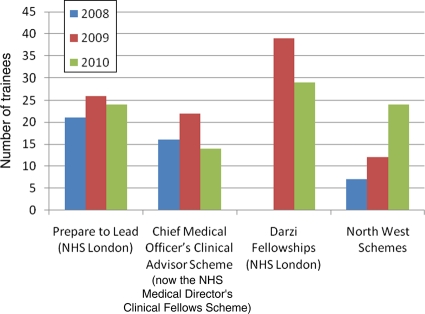

Over the last few years, opportunities for junior doctors to work as medical managers in a variety of healthcare settings have emerged (Figure 2 and Table 1). Further schemes incorporate quality improvement capability into junior doctor training, such as Beyond Audit in the London Deanery and Learning to Make a Difference at the Royal College of Physicians. These have started to foster clinical engagement in a new generation and whilst expensive to initiate, may achieve savings for organizations in the longer-term.18 However, despite these initiatives, still no formal career structures for aspiring clinical leaders exist and could be developed, similar to reforms that have taken place in academic medicine.

Figure 2.

Number of junior doctors in selected clinical leadership schemes from 2008–10

Table 1.

Leadership secondment opportunities for junior doctors in alphabetical order

| Name of program | Information |

|---|---|

| Darzi Fellowships | In 2009, following recommendations from Lord Darzi's Next Stage Review, the London Deanery funded secondments for junior doctors to learn more about health management and quality improvement. This was spread to other Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) with funding from the National Leadership Council. Each SHA has taken a different approach to their fellowships, including the use of used different names (‘Darzi Fellowships’, ‘Leadership Fellowships’). Some are hosted at SHAs whilst others at individual trusts. Some are ongoing whilst some have now stopped due to lack of funding. |

| Leadership Foundation Programme | Since 2009, Foundation Programme doctors have been able to select programmes that include a rotation to provide experience in medical management. Trusts that have offered this track include Lancashire Teaching and Royal Bolton Hospital. |

| National Leadership Council Clinical Leadership Fellowship Programme | On 12th May 2011, Secretary of State Andrew Lansley announced the creation of at least 60 clinical fellowships. The first cohort of this multi-professional programme are now in post for 2011/12. |

| NHS Medical Director's Clinical Fellows Scheme | Formerly the Chief Medical Officer's Clinical Advisor Scheme. The programme started in 2005 under Sir Liam Donaldson and has catered for almost 50 junior doctors. Recruits are seconded to work under medical directors in a range of organizations such as the Department of Health, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, World Health Organisation and BUPA. |

| NICE Scholars | Opportunities since 2010 have been available for junior doctors to work part-time at the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, developing quality standards for the NHS. |

| North West Junior Doctors Advisory Team | Started in 2002, this is ostensibly the first full-time programme for UK junior doctors. Operating across the SHA and post-graduate deanery, they were initially set up to facilitate compliance with the European Working Time Directive. Their remit now covers more broadly education and workforce issues for North West junior doctors. |

| North Western Medical Leadership Programme | Started in 2008, this programme provides part-time experience in medical management alongside clinical training for Specialty Trainees. Training is extended by a number of years and participants study towards a degree in Healthcare Leadership. |

| Third sector opportunities | These opportunities are becoming more popular with clinicians, who can work as non-clinical consultants on freelance projects. Such opportunities include McKinsey and Company, a management consultancy with a healthcare division, or Diagnosis, a clinical leadership social enterprise. |

Appropriate incentives

Pay for doctors who move into leadership roles can often decrease.11 Whilst money is not the major factor in motivating clinicians, losing income may be a strong deterrent. This is particularly relevant given overall decreasing pay, pensions and uncertain future of clinical excellence awards. Encouraging junior doctors to engage in leadership through quality improvement programmes has often brought short-term success, though longer-term benefits are unclear.19 Certain projects may also lead to efficiency savings, though can take time to be realized.

At present, incentives are non-financial for junior doctors to become involved in management. Reform of the pay structure for medical managers or altering the clinical excellence awards system may be necessary. Providing clinical commissioners with real budgets under the current reforms will provide a financial incentive, but ensuring that patients are not under-treated for financial gain is paramount.

Information systems

Ensuring the right data is available to facilitate clinical leadership is essential.12 One driver for engaging junior doctors in management is the need for them to appreciate the financial implications of clinical decision-making. Currently, FTs must implement Service Line Management, which divides the hospital into service lines providing an integrated ownership of clinical, operational and financial performance. Theoretically, each service line is incentivised to under-spend and can rate their performance against each other. With the expansion of FTs, this will become the norm and may be a lever to engage junior doctors. Better use of clinical data could also be used to demonstrate the value of clinical leadership; current evidence is often subtle and subjective, leading doctors to often be sceptical.

Conclusion

As the NHS prepares for an ‘era of austerity’, over 40,000 junior doctors are an, as yet, untapped resource to systematically improve value. Not engaging this group is like ‘trying to improve skiing by changing the rules of competition, the colour of the medals, and the location of the hill without spending much time at all on changes in skiing itself’.20 Learning from past experiences, our paper outlines some routes to improving medical engagement of junior doctors, as well as a specific call for training the next generation of clinical leaders to commission services.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

All authors have partaken in or have organized leadership development schemes for junior doctors in the NHS.

Funding and sponsorship

No external sources of funding or sponshorship were received for this paper.

Contribution statement

Benjamin Brown prepared a draft of this manuscript, to which Yasmin Ahmed-Little and Emma Stanton contributed.

Guarantor

Benjamin Brown is nominated as the guarantor for this paper.

Reviewer

Chris Ham

References

- 1.We cannot afford not to reform NHS, says David Cameron. The Independent. 2011 17 January 2011

- 2.Hamilton P, Spurgeon P, Clark J, Dent J, Armit K Engaging Doctors: Can doctors influence organisational performance? Coventry: Academy of medical royal colleges/NHS institute for innovation and improvement; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro PJ, Dorgan SJ, Richardson B A healthier health care system for the United Kingdom. McKinsey Quarterly 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keogh B Foreword. : Layla McCay SJ editor. A junior doctor's guide to the NHS. London: BMJ Group, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Percival F, Day N, Lambourne A, Bell D, Ward D An Evaluation of Consultant Input into Acute Medical Admissions Management in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins J Foundation for Excellence: an Evaluation of the Foundation Programme. London: Medical Education England, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greener I, Harrington B, Hunter D, Mannion R, Powell M Understanding the dynamics of clinico-managerial relationships. Final report London: National Institute for Health Research, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies HTO, Harrison S Trends in doctor-manager relationships. BMJ 2003;326(7390):646–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ham C Improving the performance of health services: the role of clinical leadership. Lancet 2003;361:1978–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BAMM Making Sense – a career structure for medical management. Stockport: British Association of Medical Managers; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ham C, Clark J, Spurgeon P, Dickinson H, Armit K Medical Chief Executives in the NHS: Facilitators and Barriers to Their Career Progress. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mountford J, Webb C When clinicians lead. McKinsey Quarterly 2009;9:18–25 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giordano R Leadership needs of medical directors and clinical directors. London: King's Fund, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical leadership competency framework: enhancing engagement in medical leadership. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed-Little Y, Holmes S, Brown B North West buddy scheme. BMJ Careers 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies HTO, Hodges C, Rundall T Views of doctors and managers on the doctor manager relationship in the NHS. BMJ 2003;326:626–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curry N, Goodwin N, Naylor C, Robertson R Practice-based commissioning: reinvigorate, replace or abandon. London: King's Fund, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoll L, Foster-Turner J, Glenn M Mind shift: an evaluation of the NHS London “Darzi” fellowships in clinical leadership programme. London: London Deanery, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foundation TH Involving junior doctors in quality improvement. London: The Health Foundation, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berwick DM Eleven Worthy Aims for Clinical Leadership of Health System Reform. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 1994;272(10):797–802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]