Abstract

Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid component of Coptidis Rhizoma (goldenthread) extract, has been reported to have therapeutic potential for central nervous system disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, cerebral ischemia, and schizophrenia. We have previously shown that berberine promotes the survival and differentiation of hippocampal precursor cells. In a memory-impaired rat model induced by ibotenic acid injection, the survival of pyramidal and granular cells was greatly increased in the hippocampus by berberine administration. In the present study, we investigated the effects of berberine on neurite outgrowth in the SH-SY5Y neuronal cell line and axonal regeneration in the rat peripheral nervous system (PNS). Berberine enhanced neurite extension in differentiating SH-SY5Y cells at concentrations of 0.25–3 μg/mL. In an injury model of the rat sciatic nerve, we examined the neuroregenerative effects of berberine on axonal remyelination by using immunohistochemical analysis. Four weeks after berberine administration (20 mg/kg i.p. once per day for 1 week), the thickness of remyelinated axons improved approximately 1.4-fold in the distal stump of the injury site. Taken together, these results indicate that berberine promotes neurite extension and axonal regeneration in injured nerves of the PNS.

Key Words: berberine, neurite outgrowth, regeneration, sciatic nerve injury, SH-SY5Y cell

Unlike the central nervous system, axons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) can slowly regenerate following injury. After nerve injury, the distal stump of the injury site gradually degenerates through the process of Wallerian degeneration. The degenerated axons and myelin sheaths are removed, and the microenvironment is modified to promote axonal regrowth at the nerve ending site.1,2 When axons outgrow toward the distal stump at the site of injury, Schwann cells remyelinate the new axons. It has been reported that neurotrophic factors in the injured environment, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), play an important role in the PNS regeneration.3,4 Small compounds, which act as neurotrophic factors, can also be therapeutic for improving PNS nerve regeneration.

Berberine is an alkaloid extracted from plants, such as members of the Berberidaceae family, and Coptidis Rhizoma and has antibiotic5 and anti-inflammatory6 effects. Berberine reportedly exerts neuroprotective effects in various animal disease models.7–10 Previously, we found that berberine increases the survival of hippocampal precursor cells and differentiated neurons in a dose-dependent manner, and it also promotes neuronal differentiation.8 However, whether berberine affects axonal regeneration in PNS injury models has not yet been investigated. In this study, we examined effect of berberine on neurite outgrowth in the SH-SY5Y neuronal cell line and on axonal regeneration in an injury model of rat sciatic nerve.

In animal experiments, male Sprague–Dawley rats (adult, weighing 250–270 g, obtained from Orient, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) were housed two or three per cage, allowed access to water and food ad libitum, and maintained under a constant temperature (23±1°C), humidity (60±10%), and a 12-h light/dark cycle (light on 07:00–19:00 h). Animal treatment and maintenance were carried out in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Guidelines of Kyung Hee University, Seoul.

To evaluate the effect of berberine on neurite extension in the neuronal cell line SH-SY5Y, the cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), at 37°C as previously described.11 When cells were 30% confluent, berberine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to N2 medium for 2 days at three concentrations, 0.25, 1.5, and 3 μg/mL, which showed the lowest, middle, and highest rates of cell survival in SH-SY5Y cells in our previous report.8 Retinoic acid (5 μM, Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA) was added as a positive control for neurite extension. The effect was detected using primary antibodies against neurofilament (1:1000 dilution; Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA), fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA), and propidium iodide (1 μg/mL; Sigma) by immunocytochemical analysis as previously described with modifications.2,12

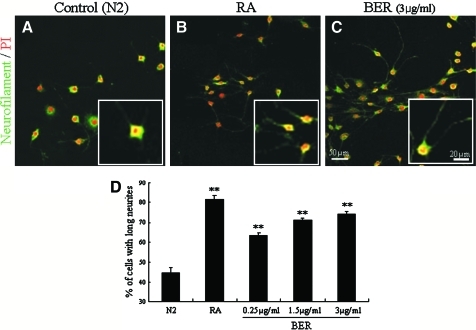

We observed that neurofilament-immunoreactive SH-SY5Y cells showed extended neurite morphology when treated with berberine (Fig. 1A–C). Because the immunoreactive cells had short neurites when treated with vehicle, the number of cells having neurites three times longer than their cell bodies was counted in a microscopic field (magnification ×200, area=211.6 mm2). The numbers of cells with longer neurites among berberine (3 μg/mL)-treated cells increased approximately 1.7-fold compared with the control group (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that berberine affects neurite extension in SH-SY5Y cells, suggesting an effect on axonal regeneration.

FIG. 1.

(A–C) Neurite extension promoted by berberine (BER) addition in the neuronal cell line SH-SY5Y. Neurites were immunostained with anti-neurofilament antibodies (green), and nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodide (PI) (red). Neurite extension was promoted in the presence of (C) BER (3 μg/mL) and (B) retinoic acid (RA) (5 μM) as a positive control compared with (A) the control (N2). (D) Quantification of cells containing long neurites (greater than three times the soma length). Data are mean±SEM values. **P<.001 compared with the control by one-way analysis of variance. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/jmf

Therefore, we investigated whether berberine could improve axonal regeneration in injured nerves of the PNS. We generated the animal model by anesthetizing the rats with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), exposed the left sciatic nerve at the sciatic notch, and then cut all nerve fibers except the artery in the sciatic nerve using iridectomy scissors under a dissection microscope. As a control, both sides of nerve fibers were tied using #9 blood vessel suture, and then the center of the nerve fibers was cut.

Berberine (20 mg/kg) or a vehicle was administered by intraperitoneal injection to the injured rats once per day for 1 week, and then nerve regeneration was assessed 1, 2, and 4 weeks after berberine injection by immunohistochemical analysis as described previously.2 After perfusion and postfixation, the distal stumps of the sciatic nerves were cryosectioned at 7–10 μm, and then the tissue slices were immunostained using primary antibodies: anti-β-tubulin isotype-III (1:1000 dilution; Sigma) to detect growing axons and anti–myelin basic protein (MBP) (1:1000 dilution; Sigma) as a marker for Schwann cell myelination. Images were scanned under an LSM 510 confocal laser microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

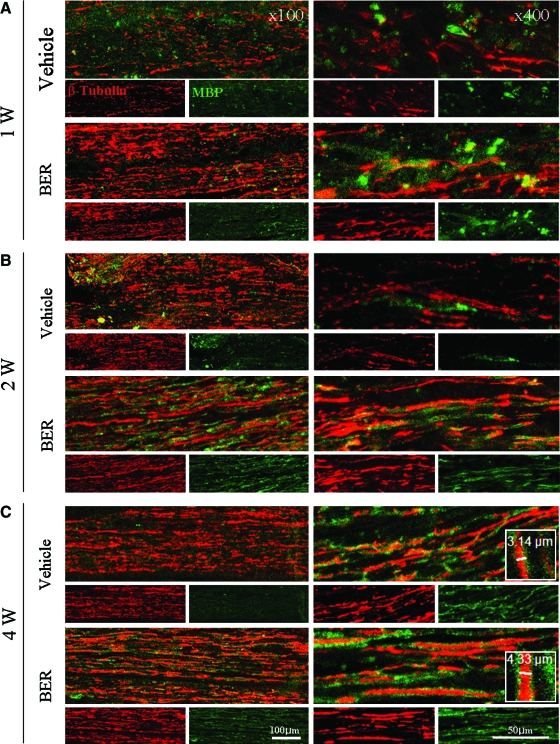

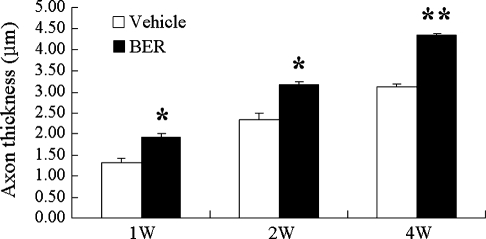

One week after the sciatic nerve injury, axons were degraded in the distal stump, and myelin sheets of Schwann cells were degraded and randomly scattered (Fig. 2A). Newly grown axons are very thin, but they get thicker when they extend and become myelinated by Schwann cells (Fig. 2B and C). Therefore, the remyelinated thick axons are considered as regenerated axons. When we measured thickness of remyelinated axons using the LSM 510 image analysis browser from 10 individual axons (n=4 animals per group), thickness was increased in berberine-treated rats compared with control animals at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after treatment (Fig. 3). At 4 weeks after berberine administration, thickness of myelinated axons was increased 1.4-fold compared with the vehicle-injected control group (Fig. 3). Moreover, we observed by immunostaining MBP that the myelin sheets surrounded the thick axons 4 weeks after berberine injection (Fig. 2C). When we counted axons longer than 300 μm in a microscopic field at the distal stumps of the injury sites (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available at www.liebertonline.com/jmf), the number of the longer axons was more than twofold greater (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Table S1) compared with controls 4 weeks after operation. These results indicate that administration of berberine improved axonal regeneration of the PNS in the rat model of sciatic nerve injury.

FIG. 2.

Sciatic nerve regeneration was improved by administration of BER (20 mg/kg) in injured rat sciatic nerves at (A) 1, (B) 2, and (C) 4 weeks after sciatic nerve injury. Axons were immunostained at the distal stump of the injured sciatic nerve with anti-β-tubulin isotype-III antibodies (red) and Schwann cells with anti–myelin basic protein antibodies (green). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/jmf

FIG. 3.

Thicknesses of myelinated axons were increased by BER treatment (20 mg/kg) in the distal stumps of injured rat sciatic nerves. Sciatic nerve regeneration was quantified at 1, 2, and 4 weeks by axonal thickness averaged from 10 axons each of four vehicle-treated and four BER-treated animals. Data are mean±SEM values. *P<.01, **P<.001 compared with the vehicle-injected group by one-way analysis of variance.

After peripheral nerve injury, the denervated nerve stump provides an appropriate environment for axonal regeneration.3 Neurotrophic factors in this microenvironment can affect regenerative processes such as neuronal survival, axonal extension, synapse reformation, and nerve regeneration.13,14 In the present study, we showed that berberine facilitated neurite extension and axonal regeneration in the PNS, and we have shown previously that it also improves neuronal survival and differentiation in the central nervous system. In addition, it has been reported in PC12 cells that co-treatment with both NGF and protoberberine alkaloid ameliorated neurite outgrowth compared with NGF treatment alone.15 However, our results show that neurite outgrowth was increased in a dose-dependent manner by a single berberine treatment in SH-SY5Y neuronal cells. These results suggest that berberine directly affects neurite regrowth in cultured SH-SY5Y cells. It has been reported that the treatment with the extract of the Ayurvedic herb Centella asiatica enhanced neurite outgrowth in cultured SH-SY5Y cells and axon regeneration in the crushed sciatic nerve model in rats.16 Therefore, we suggest that berberine plays a neuroregenerative role similar to neurotrophic factors, including NGF, and to natural products such as C. asiatica extract.

We also observed axonal regeneration in the injured sciatic nerves of rats after berberine administration. We found improvement of axonal thickness, which indicates axonal regeneration, similar to the axon area and myelin thickness, in the PNS injury.17 In addition, we observed more Schwann cells surrounding the regrowing axons in the berberine-treated animals. Schwann cells proliferate to fill the gap at the injury sites and myelinate the new axons. The axonal regeneration in the PNS largely depends on Schwann cells by releasing neurotrophic factors and guiding direction of axonal regrowth.18,19 Therefore, the remyelination of axons by Schwann cells reveals an enhancement of regeneration with berberine treatment in the rat model of sciatic nerve injury.

Our results that berberine affects axon regeneration in the injured sciatic nerve suggest that berberine may enhance neurite outgrowth in neuronal cells within the injured brain. Our previous studies have shown that cell survival was increased in the hippocampus by administration of berberine in rats with memory deficits,8 in damaged neuronal cells under oxidative stress, and in the rat model of degenerating brain disease induced by MK-801 injection.20

In conclusion, our results demonstrate for the first time that berberine treatment improves axonal regeneration in a sciatic nerve injury model. Because the axons of adult human PNS could regenerate, unlike in the central nervous system, our data imply that berberine may be a useful therapeutic compound for the human PNS after various nerve injuries and needs to be studied for clinical correlations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (2011K000262) from the Brain Research Center of the 21C Frontier Research Program funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology of Korea and by a grant from the Kyung Hee University in 2010 (KHU-20100850).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Joung I. Kim HS. Hong JS. Kwon H. Kwon YK. Effective gene transfer into regenerating sciatic nerves by adenoviral vectors: potentials for gene therapy of peripheral nerve injury. Mol Cells. 2000;10:540–545. doi: 10.1007/s10059-000-0540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon YK. Bhattacharyya A. Alberta JA, et al. Activation of ErbB2 during Wallerian degeneration of sciatic nerve. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8293–8299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08293.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michalski B. Bain JR. Fahnestock M. Long-term changes in neurotrophic factor expression in distal nerve stump following denervation and reinnervation with motor or sensory nerve. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1244–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omura T. Sano M. Omura K, et al. Different expressions of BDNF, NT3, and NT4 in muscle and nerve after various types of peripheral nerve injuries. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2005;10:293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.10307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirska I. Kedzia H. Kowalewski Z. Kedzia W. The effect of berberine sulfate on healthy mice infected with Candida albicans. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1972;20:921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marinova EK. Nikolova DB. Popova DN. Gallacher GB. Ivanovska ND. Suppression of experimental autoimmune tubulointerstitial nephritis in BALB/c mice by berberine. Immunopharmacology. 2000;48:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni SK. Dhir A. Berberine: a plant alkaloid with therapeutic potential for central nervous system disorders. Phytother Res. 2010;24:317–324. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim JS. Kim H. Choi YS, et al. Neuroprotective effects of berberine in neurodegeneration model rats induced by ibotenic acid. Anim Cells Syst. 2008;12:203–209. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo KY. Hwang IK. Kim JD, et al. Antiinflammatory effect of the ethanol extract of Berberis koreana in a gerbil model of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1527–1532. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu F. Qian C. Berberine chloride can ameliorate the spatial memory impairment and increase the expression of interleukin-1beta and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the rat model of Alzheimer's disease. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heo SR. Han AM. Kwon YK. Joung I. p62 protects SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells against H2O2-induced injury through the PDK1/Akt pathway. Neurosci Lett. 2009;450:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo H. Shin Y. Cho W. Choi Y. Kim H. Kwon YK. Memory improvement in ibotenic acid induced model rats by extracts of Scutellaria baicalensis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon YK. Effect of neurotrophic factors on neuronal stem cell death. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;35:87–93. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.1.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo M. Joung I. Han AM. Yoon HH. Kwon YK. Distinct effect of neurotrophins delivered simultaneously by an adenoviral vector on neurite outgrowth of neural precursor cells from different regions of the brain. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:2033–2041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shigeta K. Ootaki K. Tatemoto H. Nakanishi T. Inada A. Muto N. Potentiation of nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by a Coptidis Rhizoma extract and protoberberine alkaloids. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:2491–2494. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soumyanath A. Zhong YP. Gold SA, et al. Centella asiatica accelerates nerve regeneration upon oral administration and contains multiple active fractions increasing neurite elongation in-vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:1221–1229. doi: 10.1211/jpp.57.9.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jungnickel J. Haase K. Konitzer J. Timmer M. Grothe C. Faster nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve injury in mice over-expressing basic fibroblast growth factor. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:940–948. doi: 10.1002/neu.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fawcett JW. Keynes RJ. Peripheral nerve regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai C. Peripheral glia: Schwann cells in motion. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R332–R334. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee T. Heo H. Kwon YK. Effect of berberine on cell survival in the developing rat brain damaged by MK-801. Exp Neurobiol. 2010;19:140–145. doi: 10.5607/en.2010.19.3.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.