Background: Rab-type small GTPases are conserved membrane trafficking proteins in all eukaryotes.

Results: Knockdown of Rab17 in mouse hippocampal neurons results in a marked reduction in the number of dendritic branches and total dendrite length.

Conclusion: Rab17 regulates dendritic morphogenesis and postsynaptic development in hippocampal neurons.

Significance: Our findings reveal the first molecular link between membrane trafficking and dendritogenesis.

Keywords: Dendrite, Endosomes, Membrane Trafficking, Neurons, Rab Proteins

Abstract

Neurons are compartmentalized into two morphologically, molecularly, and functionally distinct domains: axons and dendrites, and precise targeting and localization of proteins within these domains are critical for proper neuronal functions. It has been reported that several members of the Rab family small GTPases that are key mediators of membrane trafficking, regulate axon-specific trafficking events, but little has been elucidated regarding the molecular mechanisms that underlie dendrite-specific membrane trafficking. Here we show that Rab17 regulates dendritic morphogenesis and postsynaptic development in mouse hippocampal neurons. Rab17 is localized at dendritic growth cones, shafts, filopodia, and mature spines, but it is mostly absent in axons. We also found that Rab17 mediates dendrite growth and branching and that it does not regulate axon growth or branching. Moreover, shRNA-mediated knockdown of Rab17 expression resulted in a dramatically reduced number of dendritic spines, probably because of impaired filopodia formation. These findings have revealed the first molecular link between membrane trafficking and dendritogenesis.

Introduction

Neurons are highly polarized cells with two distinct subcellular compartments that are highly specialized sites for information input and output, i.e. dendrites and axons, respectively. Extensive dendritic morphogenesis, which includes the generation and elaboration of extensive dendrite arbors followed by retraction and pruning, occurs in the brain to establish proper neural circuits (1). During the maturation step of dendritogenesis, filopodia from the dendritic shaft are morphologically and functionally converted into spines, which are tiny bulbous protrusions that receive input through a single synapse with an axon (2). The dendritic morphogenesis is crucial to the proper formation of neuronal circuits, because defects in dendrite patterning and/or spine formation often cause severe neurodevelopmental disorders (1, 2). However, the molecular mechanisms by which dendritogenesis and postsynaptic development occur are poorly understood.

Membrane trafficking is a well known biological process that is involved in a wide variety of cellular events, including cell polarization. In neurons, for example, axon-specific molecules (e.g. glutamate transporter and synaptotagmin I) (3, 4) and dendrite-specific molecules (e.g. AMPA receptors and NMDA receptors) (5, 6) are thought to be targeted to axons and dendrites, respectively, by individual as yet unestablished trafficking mechanisms. Rab small GTPases are conserved membrane trafficking proteins in all eukaryotes, and they mediate various steps in membrane trafficking, including vesicle budding, vesicle movement, vesicle docking to specific membranes, and vesicle fusion. The numbers of Rab isoforms vary with the species, ranging from 11 in budding yeasts to ∼60 in mammals, and the expansion in the number of Rab isoforms in higher eukaryotes is likely to be related to specialized membrane trafficking pathways in specialized cell types (7, 8). Some Rab proteins have actually been shown to be specifically localized in axons and to operate axon-specific trafficking events (e.g. Rab3 and Rab27 in synaptic vesicle trafficking) (9–11). Involvement of other Rab isoforms in postsynaptic functions has also been reported (12–16), but they are not dendrite-specific Rab proteins (i.e. they are also present and function in axons; see Refs. 17 and 18), and no Rab protein that specifically functions in dendritic morphogenesis has ever been reported.

In this study, we discovered that Rab17 is the only Rab isoform that is predominantly targeted to the dendrites of mouse hippocampal neurons. Rab17 is localized at dendritic growth cones, shafts, filopodia, and mature spines, but it is mostly absent in axons. We also found that Rab17 mediates dendrite growth and branching but that it does not regulate axon growth or branching. Moreover, knockdown of Rab17 expression resulted in a dramatically reduced number of spines probably because of impaired filopodia formation. Possible functions of Rab17 in dendritic morphogenesis and postsynaptic development are discussed based on our findings.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

The following antibodies used in this study were obtained commercially: anti-actin goat polyclonal antibody and anti-c-Myc (9E10) mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); anti-actin mouse monoclonal antibody (ABM, Richmond, Canada); anti-neurofilament-H mouse monoclonal antibody (American Research Products, Belmont, MA); anti-Tau (5E2) mouse monoclonal antibody, anti-NMDAR1 (MAB363) mouse monoclonal antibody, anti-GluR2 (MAB397) mouse monoclonal antibody, and anti-MAP2 chick polyclonal antibody (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA); anti-calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α (CaMKIIα)2 (6G9) mouse monoclonal antibody (Calbiochem, La Jolla, LA); anti-PSD95 (7E3–1B8) mouse monoclonal antibody (Pierce); anti-EEA1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); anti-EEA1 mouse monoclonal antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); anti-GFP rabbit polyclonal antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-GAPDH (3H12) mouse monoclonal antibody (MBL, Nagoya, Japan); anti-synaptophysin (SVP-38) monoclonal antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-FLAG tag (M2) mouse monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich); and anti-Rab11 rabbit polyclonal antibody and Alexa 488/594/633-conjugated anti-mouse/rabbit/goat/chick/guinea pig IgG goat antibody (Invitrogen). Anti-synaptotagmin (Syt) I N-terminal rabbit polyclonal antibody was prepared as described previously (19). Anti-Rab17 rabbit polyclonal antibody and anti-GFP guinea pig polyclonal antibody were raised against GST-Rab17 and GST-EGFP, respectively, and affinity-purified by exposure to antigen-bound Affi-Gel 10 beads (Bio-Rad) as described previously (20).

Plasmid Construction

pEGFP-C1 vectors (Clontech) harboring cDNAs of 41 different human or mouse Rab proteins were prepared as described previously (21). The Myc tag was added to the N terminus of Rab17 by PCR with a primer encoding the Myc tag sequence (in italics below) and SP6 primer by using pGEM-T-Rab17 as a template: Myc-Rab17 primer, 5′-TAAGATCTATGGAGCAAAAGCTCATTTCTGAAGAGGACTTGAATGAAGGATCCATGGCGCAGGCTGCTGG-3′. Purified PCR products were inserted into the pGEM-T Easy vector and verified by DNA sequencing. The full-length Rab17 insert with Myc tag was then excised from the pGEM-T Easy vector by NotI digestion and subcloned into the NotI site of the modified pEF-BOS (22) (named pEF-Myc-Rab17). pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo vector (Ambion, Austin, TX) encoding a mouse Rab17 shRNA (19-base target site: 5′-TGCTGCGCTCCTGGTTTAT-3′) was constructed as described previously (23). pSilencer-EGFP vector was generated from pSilencer 2.1-U6 neo vector by digesting the XmaI/NruI site and by substituting it for the Xma1/HpaI site of pEGFP-N1. An shRNA-resistant Rab17 mutant (named Rab17SR) was produced by the two-step PCR techniques essentially as described previously (24). In brief, PCRs were performed to generate two DNA fragments having overlapping ends into which specific alterations were introduced, e.g. Rab17-SR-5′ primer, 5′-CAGGGGTGCCAACGCAGCCTTATTAGTGTACGACATCACTCGG-3′; and Rab17-SR-3′ primer, 5′-CCGAGTGATGTCGTACACTAATAAGGCTGCGTTGGCACCCCTG-3′ (substituted nucleotides are shown in italics). After purification of the two DNA fragments, they were combined to generate the fusion product by a second PCR. The resulting mutant Rab17 cDNAs were subcloned into the pME18S expression vector (25) or pEGFP-C1 vector. PSD95-EGFP expression vector was constructed according to Okabe et al. (26). pCAG-gap-Venus was prepared as described previously (27). pCAG-Control was constructed by removing the gap-Venus insert by EcoRI digestion followed by self-ligation, and pCAG-Myc-Rab17-Q77L and pCAG-Myc-Rab17-T33N were constructed by replacement of the gap-Venus insert by the Myc-Rab17-Q77L fragment and Myc-Rab17-T33N fragment (28, 29), respectively.

Hippocampal Neuron Culture and Transfection

Mouse hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared essentially as described previously (30). In brief, hippocampi were dissected from embryonic day 16.5 mice and dissociated with 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen). The cells were plated at a density of 3–6 × 104 cells onto coverglasses in a 6-well plate or glass-bottomed dishes (35-mm dish; MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA) coated with poly-l-lysine hydrobromide (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). They were maintained in minimum essential medium containing B27 supplements, 1% fetal bovine serum, and 0.5 mm glutamine (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNAs were transfected into neurons at 2–4 days in vitro (DIV) by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Other Cell Cultures and Transfections

COS-7 cells and Neuro2A cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 units/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were plated onto a 6-well plate. Plasmid DNAs were transfected into COS-7 cells and Neuro2A cells by using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) and Lipofectamine 2000, respectively, each according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunocytochemistry

Neurons were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako Pure Chemicals Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer at room temperature. After permeabilizing the cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 min, they were blocked with the blocking buffer (10% FBS in PBS) for 1 h. The cells were then immunostained for 1 h with anti-MAP2 chick antibody (1/1000 dilution), anti-neurofilament-H mouse antibody (1/500 dilution), anti-Tau mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-Myc mouse antibody (1/200 dilution), anti-EEA1 rabbit antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-EEA1 mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-Rab11 rabbit antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-Rab17 rabbit antibody (1/200 dilution), anti-GFP rabbit antibody (1/500 dilution), anti-GFP guinea pig antibody (1/500 dilution), anti-synaptophysin mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-GluR2 mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-NMDAR1 mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), anti-CaMKIIα mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), and anti-PSD95 mouse antibody (1/100 dilution), after which they were incubated for 1 h with Alexa-Fluor 488/594/633-labeled secondary IgG (1/5000 dilution) or Texas Red-coupled phalloidin (1/100) at room temperature. Surface NMDAR1 was stained by anti-NMDAR1 mouse antibody before the permeabilization step. The cells were examined for fluorescence with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Fluoview 1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and the images were processed with Adobe Photoshop software (CS4). Fluorescent intensity or the number of fluorescent dots was quantified with ImageJ software (version 1.42q; National Institutes of Health). Typical images of neurons are shown in each figure.

Immunoblotting

Mouse tissue homogenates or total hippocampal cell homogenates (31) were suspended in the SDS sample buffer. For immunoblotting, the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) by electroblotting. The blots were blocked with 0.3% skim milk and 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS, and after incubating them with a primary antibody, they were washed with PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 and incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Morphometric Analyses of Neurites in Hippocampal Neurons

Neurites were morphometrically analyzed as described previously with slight modifications (32). Hippocampal neurons were fixed at the DIV indicated in each figure (e.g. 11 DIV in Fig. 4C for Rab17 knockdown and 4 DIV in Fig. 5C for Rab17-QL overexpression) to optimize the effect of their treatment. The cells were then subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP, MAP2, and neurofilament-H (or Tau). All of the quantitative analyses were carried out based on immunostaining of the morphometric marker GFP. Dendrites and axons were identified based on the presence of a dendrite-specific marker (MAP2) and an axon-specific marker (neurofilament-H or Tau), respectively. Total dendrite length, total dendrite branch tip numbers, total axon length, and total axon branch tip numbers were determined manually by using NeuronJ (version 1.1.0) (33) plug-in software for ImageJ. The length of each neurite was measured from the edge of the cell body (or its branching point) to the tip of the neurite, and total dendrite (or axon) length means the sum of the lengths of all of the dendrites (or axons) of that neuron (see supplemental Fig. S1).

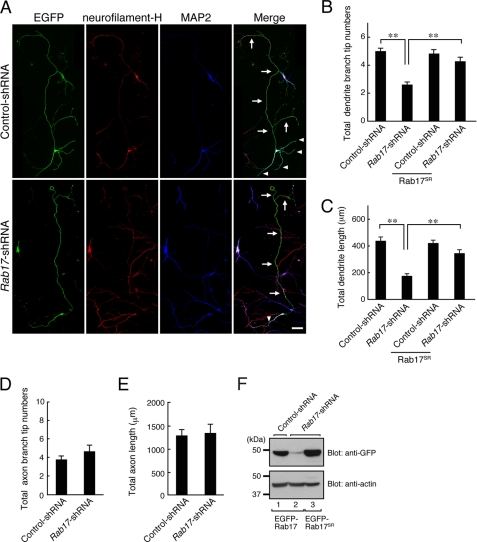

FIGURE 4.

Rab17 regulates dendritic morphogenesis in hippocampal neurons. A–C, at 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding EGFP and control shRNA (upper panels in A) or Rab17 shRNA (lower panels in A), and the neurons were fixed at 11 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP, neurofilament-H (red), and MAP2 (blue). A, typical images of Rab17 knockdown neurons. The arrows and arrowheads indicate axons and dendrites, respectively. Bar, 50 μm. B and C, quantification of total dendrite branching tip numbers (B) and total dendrite length (C) of the control neurons (n = 52), Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 47), Rab17SR-expressing control neurons (n = 54), and Rab17SR-expressing Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 62). Note that both the total dendrite length and total dendrite branching tip numbers of Rab17 knockdown neurons were significantly lower than in the control cells. **, p < 0.0025. D and E, quantification of total axon branching tip numbers (D) and total axon length (E) of control neurons (n = 25) and Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 25). Dendrites (MAP2-positive neurites) and axons (neurofilament-H-positive neurites) were analyzed separately. **, p < 0.0025. F, knockdown efficiency of Rab17 shRNA. COS-7 cells were transfected with a vector encoding control shRNA or with Rab17 shRNA together with EGFP-Rab17 (lanes 1 and 2) or EGFP-Rab17SR (lane 3), and 2 days after transfection the cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-GFP antibody (upper panel) and anti-actin antibody (lower panel). The positions of the molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left.

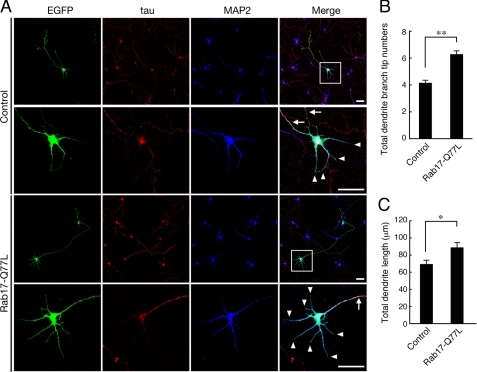

FIGURE 5.

Overexpression of Rab17-Q77L, a constitutive active Rab17 mutant, promotes dendritic morphogenesis in hippocampal neurons. A–C, at 2 DIV hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with a vector encoding EGFP and pCAG control (top row and second row in A) or pCAG-Myc-Rab17-Q77L (third row and bottom row in A), and the neurons were fixed at 4 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP (green), Tau (red), and MAP2 (blue). A, typical images of Rab17-Q77L-expressing neurons. Bars, 20 μm. The second row and bottom row of panels are magnified views of the boxed areas in the far-right panels in the top row and the third row, respectively. B and C, total dendrite branching tip numbers (B) and the total dendrite length (C) of the control neurons (n = 79) and Rab17-Q77L-expressing neurons (n = 80) were analyzed. **, p < 0.0025; *, p < 0.01.

Determination of Spine and Synapse Numbers

Spine and synapse numbers were determined as described previously with slight modifications (27, 30). To determine spine numbers, hippocampal neurons were fixed at 24 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against CaMKIIα or PSD95 (spine markers) and MAP2. Dendritic spines were identified as CaMKIIα or PSD95-positive protrusions that had mushroom-shaped heads. To determine synapse numbers, hippocampal neurons expressing PSD95-EGFP were fixed at 21 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP, synaptophysin (a presynapse marker), and MAP2. When a PSD95-EGFP-positive dot overlapped a synaptophysin-positive dot by at least 0.15-μm, the PSD95/synaptophysin-positive structure was counted as a “synapse.” The density of spine dots and synapse dots was expressed as the number per 10 μm dendrite length.

Anti-Syt I-N-terminal Antibody Uptake Experiments

Anti-Syt I N-terminal (anti-Syt I-N) antibody uptake experiments were performed as described previously with slight modifications (19, 34). At 21 DIV hippocampal neurons were stimulated for 10 min at 37 °C with minimum essential medium containing 25 mm KCl and anti-Syt I-N antibody (0.5 μg/ml). The neurons were immediately washed twice with PBS, and after fixation they were subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against MAP2 and rabbit IgG (i.e. anti-Syt I-N IgG). The number of Syt I-N positive-dots was counted as the number per 10 μm of dendrite length.

Measurement of Filopodia

Filopodia were counted as described previously with slight modifications (27, 30). Live images of gap-Venus-expressing hippocampal neurons were recorded at 11 DIV through a confocal laser scanning microscope. Dendritic filopodia were defined as headless filaments that protruded more than 1.5 μm from main shaft. Filopodium density was expressed as the number per 10 μm of dendrite length.

Statistical Analyses

The results shown in Figs. 4, B–E; 5, B and C; 6, C, E, and G; and 7C and supplemental Fig. S3 are presented as the means and S.E. The values were compared with Student's unpaired t test. A p value of <0.025 was considered statistically significant. All of the statistical analyses were obtained in three independent experiments, and the data from a representative experiment are shown here.

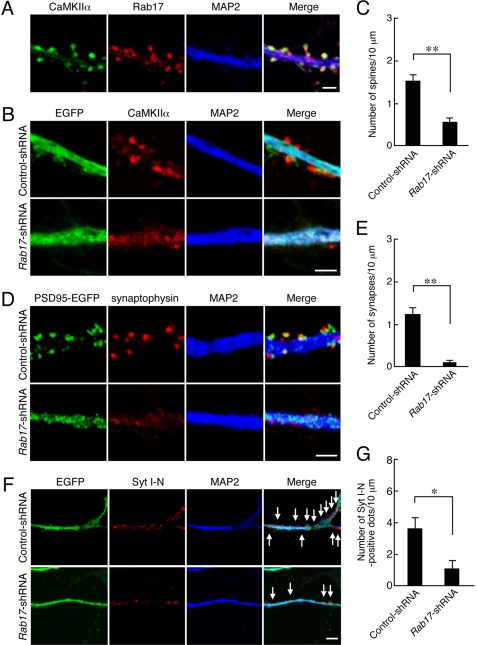

FIGURE 6.

Rab17 is necessary for postsynaptic development. A, hippocampal neurons were fixed at 24 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against Rab17 (green), CaMKIIα (a spine marker; red), and MAP2 (blue). Note that the Rab17 dots were localized at dendritic spines. Bar, 2.5 μm. B, typical images of Rab17 knockdown neurons with reduced numbers of spines and synapses. At 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding EGFP together with control shRNA (upper panels in B) or Rab17 shRNA (lower panels in B), and at 24 DIV the neurons were fixed and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP (green), CaMKIIα (red), and MAP2 (blue). Bar, 2.5 μm. C, quantification of the numbers of spines in control neurons (n = 21) and Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 20). **, p < 0.0025. D, typical images of Rab17 knockdown neurons with a reduced number of synapses. At 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding PSD95-EGFP together with control shRNA (upper panels in D) or Rab17 shRNA (lower panels in D), and the neurons were fixed at 21 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP (green), synaptophysin (a presynapse marker; red), and MAP2 (blue). Bar, 2.5 μm. E, quantification of the numbers of synapses in the control neurons (n = 20) and Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 27). **, p < 0.0025. F, typical images of Rab17 knockdown neurons with reduced numbers of functional synapses. At 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding EGFP and control shRNA (upper panels in F) or Rab17 shRNA (lower panels in F), and at 21 DIV they were incubated for 10 min with an antibody against Syt I N-terminal domain (anti-Syt I-N) in the presence of 25 mm KCl-containing medium. The neurons were then fixed and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against rabbit IgG (red) and MAP2 (blue). The arrows indicate the anti-Syt I-N antibody incorporated into neurons (red). Bar, 5 μm. G, quantification of the numbers of anti-Syt I-N antibody-positive dots in the control neurons (n = 20) and Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 25). *, p < 0.01.

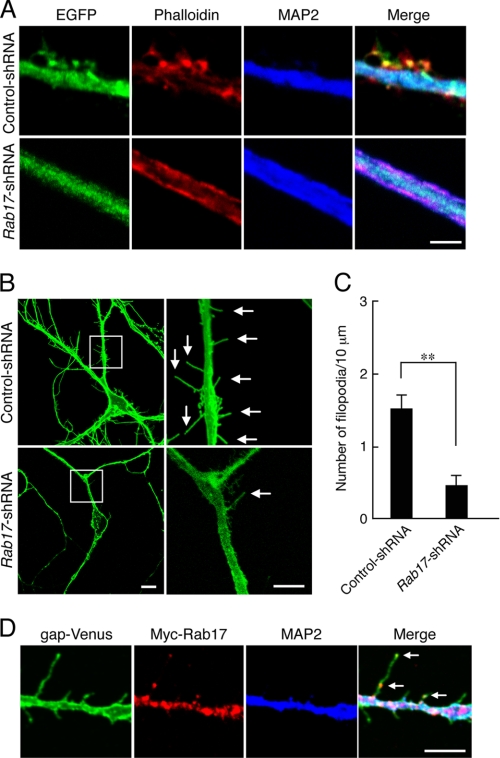

FIGURE 7.

Rab17 is required for filopodia formation in dendrites. A, at 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding EGFP and control shRNA (upper panels in A) or Rab17 shRNA (lower panels in A), and at 20 DIV the neurons were fixed, subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against EGFP (green) and MAP2 (blue), and stained for F-actin (red) with phalloidin. Bar, 2.5 μm. Note that the control neurons contain a number of protrusions, which represent spines or filopodia, whereas the dendrites of the Rab17 knockdown neurons are devoid of protrusions. B, typical images of Rab17 knockdown neurons with reduced numbers of filopodia. At 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding gap-Venus together with control shRNA (upper panels in B) or Rab17 shRNA (lower panels in B), and they were examined at 11 DIV. The right panels are magnified views of the boxed areas in the left panels. The arrows indicate filopodia. Bars, 5 μm. C, quantification of the numbers of dendritic filopodia in the control neurons (n = 25) and Rab17 knockdown neurons (n = 20). **, p < 0.0025. D, at 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were co-transfected with a vector encoding gap-Venus and Myc-Rab17, and at 12 DIV the neurons were fixed and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against Myc (red) and MAP2 (blue). The arrows indicate Rab17-positive dots in filopodia. Bar, 5 μm.

RESULTS

Rab17 Is Only Rab Isoform That Is Specifically Localized at Dendrites of Hippocampal Neurons

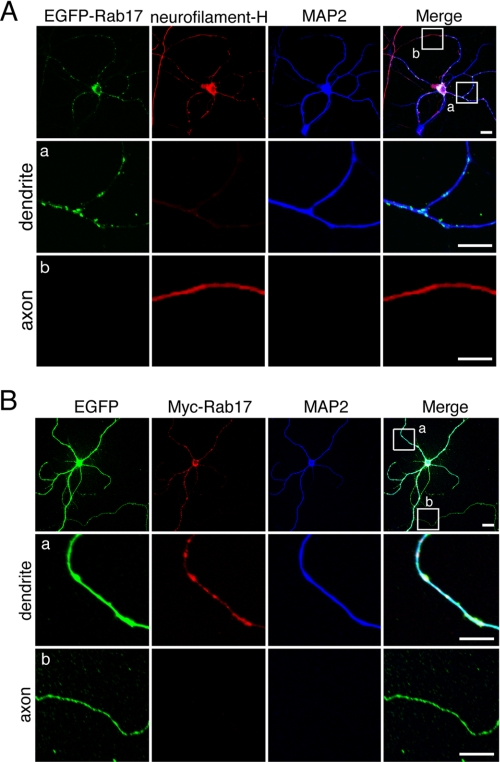

To identify Rab isoforms that specifically localize and function in dendrites, we first performed a comprehensive expression analysis of EGFP-tagged Rab proteins (Rab1–43) (21, 35) in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons. Among the 41 Rab family members analyzed, only Rab17 showed highly restricted localization to dendrites and no localization to axons (Fig. 1A and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3A; summarized in Table 1). The same dendritic localization was also observed for Myc-tagged Rab17 (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S3B), thereby excluding the possibility that N-terminal EGFP tagging artificially induces dendrite-specific localization.

FIGURE 1.

Rab17 is specifically localized at the dendrites of hippocampal neurons. A and B, at 5 DIV mouse hippocampal neurons were transfected with pEGFP-C1-Rab17 (A) or pEGFP-C1 and pEF-Myc-Rab17 (B). The neurons were fixed at 14 DIV and then subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against neurofilament-H (an axon marker; red) and MAP2 (a dendrite marker; blue) (A) or Myc (red) and MAP2 (blue) (B). The middle panels (panels a) and bottom panels (panels b) are magnified views of the boxed areas in the upper right panel. Note that punctate EGFP-Rab17 or Myc-Rab17 signals were specifically observed in the dendrites (MAP2-positive neurites, middle panels in A and B) and were not observed at all in the axons (MAP2-negative neurites, bottom panels in A and B). Bars, 10 μm.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the localization of EGFP-Rab1–43 in mouse hippocampal neurons

The EGFP-Rabs were classified into four groups according to their localization in axons and/or dendrites. The first group consists of EGFP-Rabs, whose signals were not detected as dots in either axons or dendrites (indicated as ND, for “not determined”). The second group consists of EGFP-Rabs, whose signals were detected as dots in axons, but not in dendrites (indicated as “axons”). The third group consists of just EGFP-Rab17, whose signals were detected in dendrites, but not in axons (indicated as “dendrites”). The fourth group consists of EGFP-Rabs, whose dot signals were detected in both axons and dendrites (indicated as “axons and dendrites”). Note that EGFP-Rab17 alone was localized at dendrites and not at axons. The numbers in the column on the right are the numbers of EGFP-Rab-expressing neurons analyzed in this study.

| Rab isoform | Dots in axons or dendrites | Number of neurons | Rab isoform | Dots in axons or dendrites | Number of neurons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rab1A | Axons and dendrites | 9 | Rab23 | Axons | 14 |

| Rab2A | ND | 10 | Rab24 | ND | 7 |

| Rab3A | Axons | 21 | Rab25 | Axons and dendrites | 7 |

| Rab4A | Axons and dendrites | 7 | Rab26 | Axons and dendrites | 6 |

| Rab5A | Axons and dendrites | 6 | Rab27A | Axons | 6 |

| Rab6A | Axons and dendrites | 6 | Rab28 | ND | 8 |

| Rab7 | Axons and dendrites | 9 | Rab29 | Axons | 8 |

| Rab8A | Axons and dendrites | 8 | Rab30 | Axons and dendrites | 10 |

| Rab9A | Axons and dendrites | 8 | Rab32 | Axons | 7 |

| Rab10 | Axons and dendrites | 8 | Rab33A | Axons and dendrites | 8 |

| Rab11A | Axons and dendrites | 11 | Rab34 | Axons | 6 |

| Rab12 | Axons and dendrites | 7 | Rab35 | Axons and dendrites | 11 |

| Rab13 | ND | 8 | Rab36 | Axons | 9 |

| Rab14 | Axons and dendrites | 7 | Rab37 | Axons and dendrites | 7 |

| Rab15 | Axons | 6 | Rab38 | Axons | 8 |

| Rab17 | Dendrites | 21 | Rab39A | Axons | 6 |

| Rab18 | Axons | 10 | Rab40A | ND | 5 |

| Rab19 | Axons and dendrites | 9 | Rab41 | ND | 7 |

| Rab20 | Axons and dendrites | 9 | Rab42 | Axons | 6 |

| Rab21 | Axons and dendrites | 9 | Rab43 | Axons and dendrites | 7 |

| Rab22B | ND | 6 |

Expression and Localization of Rab17 Protein in Hippocampal Neurons Is Regulated by Postnatal Development

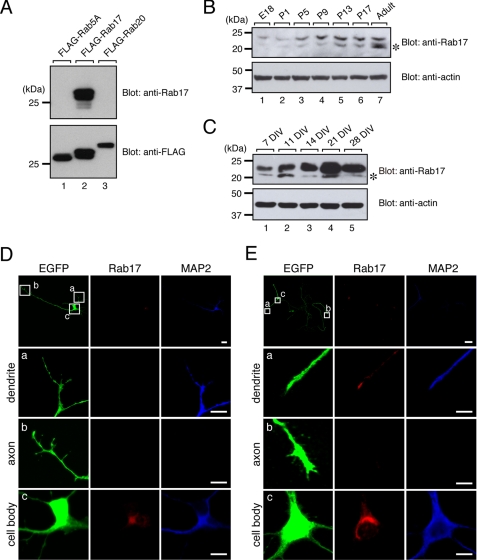

Although Rab17 was originally reported as an epithelial cell-specific Rab protein (36, 37), we were able to detect expression of endogenous Rab17 protein in the mouse total brain and hippocampus by immunoblotting with a specific antibody against Rab17 (Fig. 2, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S4). Expression of Rab17 protein started to increase at postnatal day 5 (P5), and it gradually increased until reaching adulthood (Fig. 2B). Consistent with this observation, the level of Rab17 protein expression in cultured hippocampal neurons gradually increased, and it peaked at 21 DIV (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that the expression of Rab17 protein in mouse hippocampal neurons is regulated by postnatal development.

FIGURE 2.

Expression and localization of Rab17 protein in the hippocampal neuron are developmentally regulated. A, specificity of the anti-Rab17 antibody used in this study. COS-7 cells were transfected with a vector encoding FLAG-tagged Rab5A, Rab17, or Rab20, and 2 days after transfection, the cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-Rab17 antibody (upper panel) and anti-FLAG tag antibody (lower panel). Note that Rab17 antibody specifically recognized Rab17 (upper panel, lane 2) but did not recognize its related isoforms, Rab5A and Rab20 (upper panel, lanes 1 and 3). B and C, Rab17 expression is developmentally regulated (B) in the mouse hippocampus and (C) in primary mouse hippocampal neuron cultures. Tissue homogenates (50 μg) of mouse hippocampus from embryonic day 18 (E18) to adult mice (B) or lysates of murine hippocampal neurons at 7, 11, 14, 21, or 28 DIV (C) were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Rab17 antibody (upper panels) and anti-actin antibody (lower panels). The asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. The positions of the molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left. D and E, at 2 DIV mouse hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding EGFP, and the neurons were fixed at 3 DIV (D) or 11 DIV (E) and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against GFP (green), Rab17 (red), and MAP2 (blue). The bottom three panels (panels a–c) are magnified views of the boxed areas in the upper left panels. Note that at 3 DIV, endogenous Rab17 signals were specifically observed in the cell body, and they were hardly observed in the dendrites and axons, whereas at 11 DIV some Rab17 signals were clearly observed in the dendrites, but they were rarely observed in the axons. Bars, 50 μm (top panels in D and E) and 10 μm (middle and bottom panels in D and E).

We then examined hippocampal neurons for endogenous Rab17 signals at different stages of development. At an early stage (3 DIV), Rab17 was detected only in the cell body, and it was hardly detected in dendrites and axons (Fig. 2D and supplemental Fig. S3C). At a later stage (11 DIV), however, some Rab17 signals had clearly accumulated in dendritic growth cones, and less abundant signals were also detected in dendritic shafts, but they were rarely observed in axonal growth cones or shafts (Fig. 2E and supplemental Fig. S3C). These results indicated that as dendritogenesis proceeded, Rab17 protein was translocated from the cell body to the dendrites, not to the axons.

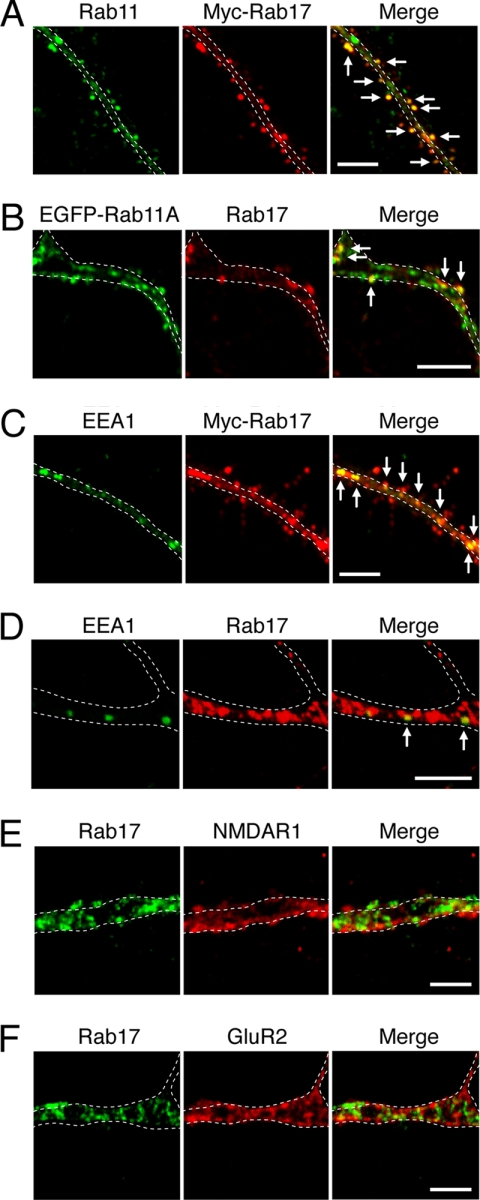

Endosomal Localization of Rab17 in Hippocampal Neurons

Because Rab17 has been shown to be localized at recycling endosomes in non-neuronal cell lines (36–38), we next investigated whether the Rab17 in neuronal dendrites is localized at the same site. As anticipated, Myc-Rab17 in dendrites significantly overlapped with Rab11, a recycling endosome marker (most co-localization points were outside the dendritic shaft; Fig. 3A, arrows), and we confirmed that endogenous Rab17 protein co-localizes with EGFP-Rab11A-positive dots (Fig. 3B, arrows). We also found that Myc-Rab17 and endogenous Rab17 co-localized with EEA1, an early endosome marker, especially in the dendritic shafts (Fig. 3, C and D, arrows). These results indicated that Rab17 protein in neuronal dendrites is localized at recycling/early endosomes. Although some postsynaptic receptors have been shown to be regulated by endosomal trafficking in mature spines (12–16), these Rab17-positive endosomes were negative for both NMDAR1 (an NMDA receptor subunit) or GluR2 (an AMPA receptor subunit) in the dendrites of developing neurons (Fig. 3, E and F).

FIGURE 3.

Endosomal localization of Rab17 in developing dendrites of the hippocampal neuron. A–C, at 4 DIV hippocampal neurons were transfected with a vector encoding Myc-Rab17 or EGFP-Rab11A. The neurons were fixed at 16 DIV (A and C) or 18 DIV (B) and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against Myc (red) and Rab11 (a recycling endosome marker; green) (A), endogenous Rab17 (red) and EGFP-Rab11A (green) (B), and Myc (red) and EEA1 (an early endosome marker; green) (C). D, partial co-localization between endogenous Rab17 and EEA1. Hippocampal neurons were fixed at 16 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against Rab17 (red) and EEA1 (green). The arrows indicate the co-localization points. E and F, Rab17 was not co-localized with the NMDA receptor or AMPA receptor in the dendrites of developing neurons. Hippocampal neurons were fixed at 18 DIV and subjected to immunocytochemistry with antibodies against Rab17 (green) and NMDAR1 (E, red) or GluR2 (F, red). The dashed lines indicate dendritic shafts identified as MAP2-positive areas. Bars, 10 μm.

Rab17 Regulates Dendritic Morphogenesis in Hippocampal Neurons

The localization of Rab17 protein at dendritic growth cones prompted us to hypothesize that Rab17 regulates dendritic morphology. To test our hypothesis, we investigated the impact of shRNA-mediated knockdown of Rab17 on the dendritic morphology of hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4, A–E) (knockdown efficiency was shown in Fig. 4F and supplemental Fig. S5). Rab17 knockdown resulted in a marked reduction in the number of dendritic branches, total dendrite length, and mean length of primary dendrites (to 46.1 ± 5.0, 29.8 ± 4.1, and 65.1 ± 8.6%, respectively, of the control) (Fig. 4, A–C). These effects could not have been caused by the off target effect of shRNA, because the abnormal dendrite patterning in Rab17 knockdown neurons was completely rescued by re-expression of shRNA-resistant Rab17SR mutant protein (Fig. 4, B and C). In striking contrast, neither axonal branching nor axonal outgrowth was affected by the Rab17 knockdown (Fig. 4, A, D, and E).

If Rab17 is a positive regulator of dendritic morphogenesis, forced activation of Rab17, i.e. overexpression of a constitutive active mutant of Rab17 (Rab17-Q77L), should increase the number of dendritic branches and/or the total dendritic length. Consistent with our hypothesis, at 4DIV both the number of dendritic branches and the total dendrite length were significantly higher in the Rab17-Q77L-expressing neurons than in the control neurons (149.3 ± 7.2 and 128.1 ± 7.9%, respectively, of the control) (Fig. 5). The above findings indicate that Rab17 plays a crucial role in dendritic morphogenesis in hippocampal neurons. We also tested the effect of a constitutive negative mutant of Rab17 (Rab17-T33N) on dendritic morphology, but we did not observe any changes in dendritic morphology, presumably because of the very low level of Rab17-T33N expression in hippocampal neurons (data not shown).

Rab17 Is Necessary for Postsynaptic Development

We then investigated the localization of Rab17 protein in mature stage neurons (24 DIV). Interestingly, Rab17 clusters were found to lie outside the MAP2-negative areas, and the clusters were highly co-localized with two spine markers: CaMKIIα and PSD95 (26, 39) (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S6A), suggesting possible involvement of Rab17 in postsynaptic development and/or synaptic function. To investigate this possibility, we monitored the number of spines in control and Rab17 knockdown neurons by visualization of CaMKIIα (or PSD95). The results clearly showed that Rab17 knockdown caused a drastic reduction in the number of spines (24.0 ± 4.6% of the control; Fig. 6, B, lower panels, and C, and supplemental Fig. S6B, lower panels), and there were concomitant decreases in the number of synapses co-visualized with EGFP-fused PSD95 (26) (a postsynaptic marker) and synaptophysin (a presynaptic marker) (8.3 ± 2.7% of the control) (Fig. 6, D and E). Moreover, we visualized presynaptic neural activity by measuring the uptake of a Syt I N-terminal antibody (19, 34). In response to high K+ stimulation, control neurons took up massive amounts of Syt I N-terminal antibody (Fig. 6F, arrows in the upper panels), whereas uptake was dramatically reduced in Rab17 knockdown neurons (29.8 ± 11.1% of the control; Fig. 6, F, lower panels, and G), indicating that Rab17 is necessary for postsynaptic development.

Rab17 Is Required for Filopodia Formation in Dendrites

How does Rab17 regulate postsynaptic development? Because dendritic spine development proceeds in two steps, i.e. the first step consisting of projection of filopodia from dendritic shafts and the second step consisting of transformation of filopodia into spines after their initial contact with axons (40, 41), we investigated whether Rab17 is involved in these steps. To this end, we first used phalloidin to visualize polymerized F-actin as a means of detecting both spines and filopodia (42). In the maturation stage (20 DIV), the control neurons exhibited a number of protrusions, which reflect spines and/or filopodia, whereas the Rab17 knockdown neurons were devoid of protrusions along their dendrites (Fig. 7A), strongly suggesting involvement of Rab17 in dendritic filopodia formation, which precedes spine formation. We therefore attempted to observe filopodia in the prematuration stage (11 DIV). To this end, we visualized the fine morphology of dendrites by expressing membrane-targeted Venus (gap-Venus) (27) and compared the number of dendritic filopodia in control neurons and Rab17 knockdown neurons. At 11 DIV, the control neurons bore numerous dendritic filopodia (Fig. 7B, arrows in the upper panels), whereas the number of dendritic filopodia was dramatically decreased in the Rab17 knockdown neurons (30.4 ± 8.9% of the control; Fig. 7, B, lower panels, and C). It should be noted that some Myc-Rab17 signals were observed in dendritic filopodia (Fig. 7D, arrows). These results, together with a recent observation that Rab17 is involved in filopodia formation in melanocytes (38), indicate that Rab17 is necessary for the formation of dendritic filopodia.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we obtained evidence that Rab17 specifically regulates dendrite development and does not regulate axon development. Because Rab17 is predominantly transported to dendrites after the establishment of neuronal polarity, one conceivable function of Rab17 is to transport specific lipids/proteins that contribute to membrane addition and/or protein trafficking in dendrites during dendritogenesis. These molecules are presumably localized at endosomes, which have often been implicated in neurite outgrowth and extension (43). Because Rab17 knockdown neurons have only a few dendrites (Fig. 4) and mostly lack dendritic filopodia (Fig. 7), possible candidate cargos of Rab17-bearing endosomes include lipids that are supplied to dendritic growth cones and filopodia and/or proteins that mediate neurite extension or branching and filopodia formation. Because some filopodia that extend from dendritic shafts have been observed to transform into growth cones and new dendrite branches (44), the abnormal dendrite branching in Rab17 knockdown neurons may be attributable to the formation of fewer filopodia.

Because Rab17 is also localized at the mature spines of dendrites (Fig. 6), Rab17 may also be involved in the transport of lipids/proteins that specifically function in mature spines. Because several Rab proteins (e.g. Rab4, Rab5, Rab8, and Rab11) have been reported to modulate postsynaptic functions, e.g. long term potentiation- and long term depression-dependent regulation of spine size (13) and AMPA receptor trafficking (12, 14–16), it is possible that Rab17 is also involved in the transport of postsynaptic receptors at the spines of mature neurons; however, we did not observe any co-localization of Rab17 with NMDAR1 (an NMDA receptor subunit) or GluR2 (an AMPA receptor subunit) in the dendrites of developing neurons (Fig. 3, E and F), and there did not appear to be any difference between control neurons and Rab17 knockdown neurons in the level of NMDAR1 expression on the cell surface (supplemental Fig. S7). Another possibility is that Rab17 contributes to precursors of spine assembly by regulating dendritic filopodia formation (Fig. 7) rather than contributing to postsynaptic function itself. Identification of cargo(s) of the Rab17-bearing vesicles/membranes will be necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which Rab17 mediates dendritic morphogenesis.

In summary, we for the first time demonstrated that Rab17, a Rab family protein predominantly localized at dendrites, regulates the morphogenesis of dendrites and not of axons. We also showed that Rab17 is localized to the spines of mature hippocampal neurons and that it participates in postsynaptic development through promotion of filopodia formation. Our discovery of novel Rab17-mediated polarized trafficking in hippocampal neurons should provide clues to the mechanism of dendritogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Megumi Aizawa for technical assistance and members of the Fukuda Laboratory for valuable discussions.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (to Y. M., Y. F., Y. Y., and M. F.) and by a grant from the Global COE Program (Basic & Translational Research Center for Global Brain Science) of the MEXT of Japan (to Y. M. and M. F.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

- CaMKIIα

- calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α

- DIV

- days in vitro

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- SR

- shRNA-resistant

- Syt

- synaptotagmin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Urbanska M., Blazejczyk M., Jaworski J. (2008) Molecular basis of dendritic arborization. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 68, 264–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoshihara Y., De Roo M., Muller D. (2009) Dendritic spine formation and stabilization. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19, 146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perin M. S., Fried V. A., Mignery G. A., Jahn R., Südhof T. C. (1990) Phospholipid binding by a synaptic vesicle protein homologous to the regulatory region of protein kinase C. Nature 345, 260–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fei H., Grygoruk A., Brooks E. S., Chen A., Krantz D. E. (2008) Trafficking of vesicular neurotransmitter transporters. Traffic 9, 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Setou M., Nakagawa T., Seog D. H., Hirokawa N. (2000) Kinesin superfamily motor protein KIF17 and mLin-10 in NMDA receptor-containing vesicle transport. Science 288, 1796–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuda S., Miura E., Matsuda K., Kakegawa W., Kohda K., Watanabe M., Yuzaki M. (2008) Accumulation of AMPA receptors in autophagosomes in neuronal axons lacking adaptor protein AP-4. Neuron 57, 730–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukuda M. (2008) Regulation of secretory vesicle traffic by Rab small GTPases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2801–2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stenmark H. (2009) Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 513–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fischer von Mollard G., Mignery G. A., Baumert M., Perin M. S., Hanson T. J., Burger P. M., Jahn R., Südhof T. C. (1990) rab3 is a small GTP-binding protein exclusively localized to synaptic vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 1988–1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu E., Kanno E., Choi S., Sugimori M., Moreira J. E., Llinás R. R., Fukuda M. (2008) Role of Rab27 in synaptic transmission at the squid giant synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16003–16008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arimura N., Kimura T., Nakamuta S., Taya S., Funahashi Y., Hattori A., Shimada A., Ménager C., Kawabata S., Fujii K., Iwamatsu A., Segal R. A., Fukuda M., Kaibuchi K. (2009) Anterograde transport of TrkB in axons is mediated by direct interaction with Slp1 and Rab27. Dev. Cell 16, 675–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerges N. Z., Backos D. S., Esteban J. A. (2004) Local control of AMPA receptor trafficking at the postsynaptic terminal by a small GTPase of the Rab family. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43870–43878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park M., Penick E. C., Edwards J. G., Kauer J. A., Ehlers M. D. (2004) Recycling endosomes supply AMPA receptors for LTP. Science 305, 1972–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown T. C., Tran I. C., Backos D. S., Esteban J. A. (2005) NMDA receptor-dependent activation of the small GTPase Rab5 drives the removal of synaptic AMPA receptors during hippocampal LTD. Neuron 45, 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park M., Salgado J. M., Ostroff L., Helton T. D., Robinson C. G., Harris K. M., Ehlers M. D. (2006) Plasticity-induced growth of dendritic spines by exocytic trafficking from recycling endosomes. Neuron 52, 817–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown T. C., Correia S. S., Petrok C. N., Esteban J. A. (2007) Functional compartmentalization of endosomal trafficking for the synaptic delivery of AMPA receptors during long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 27, 13311–13315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takamori S., Holt M., Stenius K., Lemke E. A., Grønborg M., Riedel D., Urlaub H., Schenck S., Brügger B., Ringler P., Müller S. A., Rammner B., Gräter F., Hub J. S., De Groot B. L., Mieskes G., Moriyama Y., Klingauf J., Grubmüller H., Heuser J., Wieland F., Jahn R. (2006) Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell 127, 831–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grønborg M., Pavlos N. J., Brunk I., Chua J. J., Münster-Wandowski A., Riedel D., Ahnert-Hilger G., Urlaub H., Jahn R. (2010) Quantitative comparison of glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic vesicles unveils selectivity for few proteins including MAL2, a novel synaptic vesicle protein. J. Neurosci. 30, 2–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fukuda M., Kowalchyk J. A., Zhang X., Martin T. F. J., Mikoshiba K. (2002) Synaptotagmin IX regulates Ca2+-dependent secretion in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4601–4604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fukuda M., Mikoshiba K. (1999) A novel alternatively spliced variant of synaptotagmin VI lacking a transmembrane domain. Implications for distinct functions of the two isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31428–31434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsuboi T., Fukuda M. (2006) Rab3A and Rab27A cooperatively regulate the docking step of dense-core vesicle exocytosis in PC12 cells. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2196–2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fukuda M., Aruga J., Niinobe M., Aimoto S., Mikoshiba K. (1994) Inositol-1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate binding to C2B domain of IP4BP/synaptotagmin II. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29206–29211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuroda T. S., Fukuda M. (2004) Rab27A-binding protein Slp2-a is required for peripheral melanosome distribution and elongated cell shape in melanocytes. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1195–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hara T., Miyajima A. (1992) Two distinct functional high affinity receptors for mouse interleukin-3 (IL-3). EMBO J. 11, 1875–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okabe S., Kim H. D., Miwa A., Kuriu T., Okado H. (1999) Continual remodeling of postsynaptic density and its regulation by synaptic activity. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 804–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matsuno H., Okabe S., Mishina M., Yanagida T., Mori K., Yoshihara Y. (2006) Telencephalin slows spine maturation. J. Neurosci. 26, 1776–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Itoh T., Satoh M., Kanno E., Fukuda M. (2006) Screening for target Rabs of TBC (Tre-2/Bub2/Cdc16) domain-containing proteins based on their Rab-binding activity. Genes Cells 11, 1023–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tamura K., Ohbayashi N., Maruta Y., Kanno E., Itoh T., Fukuda M. (2009) Varp is a novel Rab32/38-binding protein that regulates Tyrp1 trafficking in melanocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2900–2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Furutani Y., Matsuno H., Kawasaki M., Sasaki T., Mori K., Yoshihara Y. (2007) Interaction between telencephalin and ERM family proteins mediates dendritic filopodia formation. J. Neurosci. 27, 8866–8876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ibata K., Hashikawa T., Tsuboi T., Terakawa S., Liang F., Mizutani A., Fukuda M., Mikoshiba K. (2002) Non-polarized distribution of synaptotagmin IV in neurons. Evidence that synaptotagmin IV is not a synaptic vesicle protein. Neurosci. Res. 43, 401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takemoto-Kimura S., Ageta-Ishihara N., Nonaka M., Adachi-Morishima A., Mano T., Okamura M., Fujii H., Fuse T., Hoshino M., Suzuki S., Kojima M., Mishina M., Okuno H., Bito H. (2007) Regulation of dendritogenesis via a lipid-raft-associated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase CLICK-III/CaMKIγ. Neuron 54, 755–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meijering E., Jacob M., Sarria J. C., Steiner P., Hirling H., Unser M. (2004) Design and validation of a tool for neurite tracing and analysis in fluorescence microscopy images. Cytometry A 58, 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malgaroli A., Ting A. E., Wendland B., Bergamaschi A., Villa A., Tsien R. W., Scheller R. H. (1995) Presynaptic component of long-term potentiation visualized at individual hippocampal synapses. Science 268, 1624–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fukuda M. (2010) How can mammalian Rab small GTPases be comprehensively analyzed? Development of new tools to comprehensively analyze mammalian Rabs in membrane traffic. Histol. Histopathol. 25, 1473–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hunziker W., Peters P. J. (1998) Rab17 localizes to recycling endosomes and regulates receptor-mediated transcytosis in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15734–15741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zacchi P., Stenmark H., Parton R. G., Orioli D., Lim F., Giner A., Mellman I., Zerial M., Murphy C. (1998) Rab17 regulates membrane trafficking through apical recycling endosomes in polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 140, 1039–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beaumont K. A., Hamilton N. A., Moores M. T., Brown D. L., Ohbayashi N., Cairncross O., Cook A. L., Smith A. G., Misaki R., Fukuda M., Taguchi T., Sturm R. A., Stow J. L. (2011) The recycling endosome protein Rab17 regulates melanocytic filopodia formation and melanosome trafficking. Traffic 12, 627–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Erondu N. E., Kennedy M. B. (1985) Regional distribution of type II Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 5, 3270–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saito Y., Murakami F., Song W. J., Okawa K., Shimono K., Katsumaru H. (1992) Developing corticorubral axons of the cat form synapses on filopodial dendritic protrusions. Neurosci. Lett. 147, 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ziv N. E., Smith S. J. (1996) Evidence for a role of dendritic filopodia in synaptogenesis and spine formation. Neuron 17, 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Halpain S. (2000) Actin and the agile spine. How and why do dendritic spines dance? Trends Neurosci. 23, 141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pfenninger K. H. (2009) Plasma membrane expansion. A neuron's Herculean task. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dailey M. E., Smith S. J. (1996) The dynamics of dendritic structure in developing hippocampal slices. J. Neurosci. 16, 2983–2994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.