Background: The size and/or protein nature of current von Willebrand factor (VWF)-glycoprotein (GP) Ibα inhibitors limits oral bioavailability and clinical development.

Results: Through a rational approach, a small molecule was selected that modulates the VWF-GPIb interaction.

Conclusion: Further chemical modifications will now allow full characterization and manipulation of the specific activity of the compound.

Significance: Rational design allows for the identification of small molecules that interfere with protein-protein interactions.

Keywords: Computer Modeling, Docking, Glycoprotein, Small Molecules, von Willebrand Factor, Glycoprotein Ib, SMPPIIs, Docking, Pharmacophores, von Willebrand Factor

Abstract

The von Willebrand factor (VWF) A1-glycoprotein (GP) Ibα interaction is of major importance during thrombosis mainly at sites of high shear stress. Inhibitors of this interaction prevent platelet-dependent thrombus formation in vivo, without major bleeding complications. However, the size and/or protein nature of the inhibitors currently in development limit oral bioavailability and clinical development. We therefore aimed to search for a small molecule protein-protein interaction inhibitor interfering with the VWF-GPIbα binding. After determination of putative small molecule binding pockets on the surface of VWF-A1 and GPIbα using site-finding algorithms and molecular dynamics, high throughput molecular docking was performed on both binding partners. A selection of compounds showing good in silico docking scores into the predicted pockets was retained for testing their in vitro effect on VWF-GPIbα complex formation, by which we identified a compound that surprisingly stimulated the VWF-GPIbα binding in a ristocetin cofactor ELISA and increased platelet adhesion in whole blood to collagen under arterial shear rate but in contrast inhibited ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation. The selected compound adhering to the predicted binding partner GPIbα could be confirmed by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. We thus clearly identified a small molecule that modulates VWF-GPIbα binding and that will now serve as a starting point for further studies and chemical modifications to fully characterize the interaction and to manipulate specific activity of the compound.

Introduction

Upon vascular injury, circulating plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF)4 binds to the exposed subendothelial collagen. High shear stress conditions induce conformational changes within the VWF that allow binding of the platelet glycoprotein (GP) Ib-V-IX receptor complex to the VWF-A1 domain. The intermolecular contacts are concentrated around two major interaction sites. The largest area is formed by an extended β-sheet, which consists of the β-sheet of the VWF-A1 Rossmann fold on one side and the β-switch of GPIbα on the other side. The C-terminal β-switch, a disordered loop in the unbound conformation, adopts a β-hairpin structure upon binding to VWF-A1. The second and remarkably smaller contact area encompasses interactions between the N-terminal β-finger of GPIbα and the N- and C-terminal bottom of VWF-A1 (1). The formation of this complex gives rise to the initial tethering of platelets over a damaged surface and allows stable platelet binding through additional interactions via the direct platelet collagen receptors. Because of its particular importance in thrombus formation at sites of high shear stress, the VWF-A1-GPIbα interaction is a prime target for the development of new antithrombotics (2, 3). Indeed, initial studies showed that Fab fragments of anti-GPIbα monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that block VWF binding inhibited thrombus formation in vivo without significant prolongation of the bleeding time in non-human primates (4–6). For other inhibitors of the GPIbα-VWF interaction, such as the VWF-A1 binding aptamer ARC1779 (7–9) and the humanized bivalent Nanobody® ALX-0081 (10, 11), the antithrombotic potential and safety in initial human clinical trials has been indicated.

All these molecules are however rather large, i.e. about 50 kDa for the Fab fragments, 33 kDa for the aptamer, and 28 kDa for the nanobody, and are of a protein or nucleotide nature that limits their oral availability and long term prophylactic use. A small molecule targeting the GPIbα-VWF protein-protein interaction (PPI) would circumvent these problems and might therefore be of particular interest.

Targeting a PPI with a small molecule still is challenging and complex. The large interaction surface (1500–3000 Å2) compared with typical protein-small molecule interactions (300–1000 Å2) (12, 13), the lack of distinct cavities, and the often flat and hydrophobic nature of the interface hamper the development of small molecule PPI inhibitors (SMPPIIs). The identification of “hot spots” (14, 15), i.e. small patches on the protein-protein interface responsible for the formation of the complex, has led to the discovery of some successful SMPPIIs such as inhibitors of the p53-MDM2 interaction (16–18), the antitumor agent ABT-263 targeted against anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (19, 20), which has entered phase II clinical trials, and most recently the ledgins that prevent HIV replication by inhibiting the LEDGF-p75-integrase interaction (21). The emerging numbers of SMPPIIs additionally allowed a more precise description of their physicochemical properties, which differ somewhat from conventional drugs (22).

We now aimed to identify such a SMPPII targeting the VWF-GPIbα interaction. Mutagenesis studies and crystal structure analysis of both interaction partners alone or in complex have led to a precise characterization of the VWF-A1-GPIbα interaction surface (1, 23). In this study, we made use of this information to identify a compound capable of influencing binding parameters by strategically targeting potential small molecule binding pockets. Extensive computational docking led to a short list of best scoring compounds, which were tested in vitro for their effect on GPIbα-VWF binding. This resulted in the characterization of a small molecule that increased the ristocetin-induced GPIbα-VWF binding in ELISA and stimulated thrombus formation in flow chambers, but interestingly it inhibited ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation in platelet-rich plasma.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Determination of Small Molecule Binding Pockets

The following x-ray structures were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (24): 1AUQ (25), 1IJB (26), 1OAK (27), 1FNS (28), 1SQ0 (1), 1M10 (29), 1UEX (30), 1IJK (26), and 1U0N (31) for VWF-A1; and 1P9A (32), 1SQ0, 1M10, and 1U0N for GPIbα. PASS and HotPatch (33, 34) in combination with the outcome of the Site Finder algorithm available in MOE (MOE2008.10, Chemical Computing Group) were used to identify a number of putative pockets that might accommodate small molecule binders. All these site-finding algorithms detect cavities near the protein surface and assign to these pockets a probability for binding small molecules. PASS uses geometrical information such as size, shape, and burial extent of buried volumes in proteins. HotPatch uses statistical models and neural networks. The algorithm detects and evaluates pockets with unusual physicochemical properties and estimates the probability that these patches belong to functional sites. The MOE Site Finder represents the predicted sites by “α spheres,” i.e. spheres that contact four atoms on their boundaries but do not contain any atoms inside their volume. These α spheres are then further analyzed and classified as either hydrophobic or hydrophilic. Hydrophilic spheres that are not located near the hydrophobic spheres are omitted, because they probably correspond to water sites. The remaining spheres are clustered using a single linkage clustering algorithm, and the result is a collection of sites, the potential pockets. These sites are ranked based on the number of hydrophobic contacts in the receptor. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried out on selected crystal structures of VWF-A1 and GPIbα. In this way, the predicted pockets were checked for their stability. If a pocket was closed during the largest part of the simulation, a small molecule would only have a negligible chance of entering and binding in the pocket. A 5-ns MD run was set up for VWF-A1. Because of its size and conformational flexibility in the β-switch region, GPIbα was submitted to a 10-ns MD run. These simulations were done using the GROMACS package version 3.1.1 (35) and the OPLS/AA (36) force field. The proteins were put in a trigonal box and solvated with TIP3P water molecules (37). A distance of 0.85 nm was respected between each protein atom and the box edge. Counter-ions were added to ensure a neutral protein charge. A conjugate gradient energy minimization of 5000 steps was applied to relieve unfavorable contacts. An equilibration step of 100 ps at constant pressure (NPT ensemble) was carried out with position restraints on all heavy protein atoms to allow relaxation of the solvent molecules. Pressure and temperature were coupled separately to an external bath using the Berendsen coupling method (38) at 298 K and 1 bar for the proteins and the solvent atoms (including counterions) throughout the simulation. Periodic boundary conditions were set in all directions. Short range nonbonded interactions were cut off at 1.4 ns, and the particle-mesh Ewald (PME) summations scheme (39) was used to calculate long range electrostatic interactions. All bonds were constrained using the LINCS algorithm (40) with a 2-fs integration step. Pocket stability was studied using VMD and root mean square deviation plots.

Creation of Three-dimensional Small Compound Databases and High Throughput Molecular Docking

On-line available small molecule databases from two different companies Asinex (Moscow, Russia) and Enamine (Kiev, Ukraine) were downloaded and preprocessed using FILTER2 and OMEGA2 (both OpenEye Scientific Software Inc, Santa Fe, NM). FILTER2 removes molecules with undesirable properties, such as toxic functionalities, a high likelihood of binding covalently with the target protein, interference with the experimental assay, and/or a low probability of oral bioavailability. Multiconformer databases were then generated with OMEGA2, using the MMF94s forcefield (41) and a root mean square deviation cutoff value of 0.7. The resulting three-dimensional databases were merged into one large database, which was filtered according to in-house developed SMPPII-like criteria (42), and guided by conclusions from Oprea (43) and Sperandio et al. (22). Next, a diverse subset creation using MOE was carried out to further reduce the size of the database. Filtering and downsizing the databases result in a limited amount of compounds to be processed and a reduction of computation time. The resulting compounds were docked into the putative binding pockets using the GOLD 3.0 (The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK). Evaluation of docked binding poses was carried out using the ChemScore, GoldScore, and Astex Statistic Potential scoring functions.

Effect of Compounds in Ristocetin Cofactor ELISA

The in vitro capacity of the selected compounds to modulate the ristocetin-induced binding of VWF to the recombinant N-terminal domain of GPIbα (further named rGPIbα) was assessed in a ristocetin co-factor ELISA based on the protocol described previously (44). The rGPIbα fragment covering residues His-1 to Val-289 was produced in CHO cells as described in Vanhoorelbeke et al. (44) and Schumpp-Vonach et al. (45). Briefly, rGPIbα is captured on microtiter plates using the anti-GPIbα mAb 2D4. After a washing step, a solution containing 5–200 μm compound, 1% DMSO, and a 1/32 dilution of pooled normal human plasma (NHP) as a source of VWF in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 (TBS-T) was added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Next, ristocetin (abp, New York) was added to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, and the mixture was incubated for another 1.5 h at 37 °C to induce VWF-GPIbα binding. 0.5 μg/ml of the inhibitory anti-GPIbα mAb 6B4 (4–6) and 25 μg/ml of the VWF-activating mAb 1C1E7 (46, 47) were used as a control. The mAb 1C1E7 renders the VWF more accessible for GPIbα binding by disrupting the interaction of the VWF D′D3 that shields the VWF-A1 domain. After incubation with anti-VWF polyclonal antibodies labeled with horseradish peroxidase (anti-VWF-Ig-HRP, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), visualization was done with ortho-phenylenediamine (Sigma) and determination of the absorbance at 490 nm.

Effect of Compounds on Ristocetin-induced Platelet Aggregation

The effect of the compounds on ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation was determined based on light transmission in a Chrono-Log dual channel aggregometer (Kordia BV, Leiden, the Netherlands) as described before (48). Briefly, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-poor plasma were prepared by differential centrifugation of whole blood taken on 0.313% citrate. The platelet count was adjusted with autologous platelet-poor plasma to 250,000 platelets/μl. Different concentrations of ristocetin, ranging from 0.8 to 1.6 mg/ml, were added to the PRP to determine the minimal amount of ristocetin needed to induce platelet aggregation. Alternatively, platelet aggregation was stimulated upon addition of ADP (5.8–6.4 μm, Sigma) or collagen (4 μg/ml, ABP, Middlesex, UK). PRP was preincubated for 3 min at 37 °C with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% DMSO with or without the compound. ATP secretion upon ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation was determined in a luciferin-luciferase assay (Chrono-Lume kit, Kordia BV) and measured on a Chrono-Log Model 700 whole blood/optimal lumi-aggregometer (Chrono-Log, Kordia BV).

Effect of Compounds on Thrombus Formation under Flow Conditions

To evaluate the effect of the respective compounds on thrombus formation under arterial blood flow conditions, platelet adhesion to collagen type III at a wall shear rate of 2600 s−1 (shear stress of 100 dyne/cm2) was assessed in a custom-made single pass flow chamber coupled to a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). After a wash step with 2 m HCl in ethanol and water, coverslips (24 mm wide × 40 mm long, Menzel-Gläser, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were coated overnight with 200 μg/ml collagen type III (collagen from human placenta, Sigma) in PBS. Next the coverslips and flow chamber were blocked for 30 min with 1% BSA, 0.1% glucose in HEPES. Blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, who had not taken aspirin or analogues during the previous 10 days, on low molecular weight heparin (25 units/ml Clexane in 0.9% NaCl, Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, France). Before the 5-min perfusion, blood was incubated for 3 min at 37 °C with the respective compounds or controls. After perfusion, the coverslips were rinsed with HEPES-buffered saline, fixated with 0.5% glutaraldehyde, and stained with May-Grünwald/Giemsa. Platelet adhesion was light microscopically evaluated at ×200 magnification. Adhesion of platelets from three different donors was expressed as the percentage of total surface covered with platelets in five consecutive fields, analyzed using the Lucia G version 4.81 software (Laboratory Imaging, Prague, Czech Republic). Platelet counts were measured before addition of the compound and at the end of the experiment.

Detection of Analogues by Molecular Fingerprinting

Analogues of hits determined by in vitro testing were detected by similarity searching through molecular fingerprinting in MOE, using MACCS Structural Keys (49) and the three-point pharmacophore fingerprint systems. Molecules with similar structures might display increased activity compared with the parent compound. The MACCS scheme (49) indicates the presence of one of the 166 Public Molecular Design Ltd. MACCS structural binary keys. When assigning a MACCS fingerprint to a molecule, this is checked for the presence of each of the 166 structural keys, which all have a determined position in the resulting 166-long bit vector. In the three-point pharmacophore system, the fingerprint is calculated from the three-dimensional conformation of the molecules. An atom type, selected from three atomic properties, is assigned to each atom. These properties refer to the presence of the atoms in a functional group such as an aromatic ring or a hydrogen bond acceptor, for example. Finally, all atom triplets are coded as features using three inter-atomic distances and three atom types of each triangle. The similarity of a molecule's fingerprint in a database, compared with that of the query molecule, is measured by the Tanimoto coefficient TC.

Binding Free Energy Calculations

Binding free energy calculations were performed to predict and estimate the effect of G6 (bound to GPIbα) on the total energy of the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex. MD simulations of 10 ns were carried out on GPIbα on the bound conformation (extracted from the 1SQ0 co-crystal structure) in the absence and presence of a small molecule docked onto it. The simulations were carried out as described above, with the following adaptations: an updated version of GROMACS (4.5.3) was used; the force field was changed to the Amber99sb force field (50), which is capable of handling small molecules; the protein was placed in a dodecahedral box; and the system was minimized through 5000 steps of steepest descent followed by 500 steps of conjugate gradient energy minimization. The 100-ps equilibration step was performed at constant pressure (NPT ensemble using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat (51)) and at constant volume (NVT), and the V-rescale (modified Berendsen) coupling method (52) was applied.

Every 100 ps, 25 snapshots were taken, mounting up to a total of 2500 snapshots over the total trajectory. Solvent and counter-ions were removed from these snapshots. Next, MM/GBSA calculations were performed for the decomposition of the binding free energy of the interactions. These simulations were performed using an implementation of the Onufriev model (53) in the Amber 8 package (54). The absolute binding energy of each complex is calculated as the difference between the free energy of the complex and its constituents. The binding free energy of each molecule contributing to the complex consists of enthalpic and entropic contributions as shown in Equation 1,

where TS represents the configurational entropy term, and Egas and Gsolv stand for the gas-phase free energy and the solvation free energy, respectively. The two last terms can be estimated through a thermodynamic cycle by the decomposition of the binding energy in a gas phase free energy and a solvation free energy, and this results in an estimation of Gsub-tot = Egas + Gsolv, which we will now call the binding free energy. This is done by a transfer of each system individually (free ligand, free receptor, and complex) from the gas to the solution phase. The gas phase free energy can be calculated from a standard force field as shown in Equation 2,

where Eint is a combination of internal energy terms (bonds, angles, and dihedral torsion), and Evdw and Eelec are the internal van der Waals and electrostatic interactions between the proteins, respectively. Polar as well as apolar terms constitute the solvation free energy shown in Equation 3,

GGB represents the polar solvation, calculated by the generalized Born (MM/GBSA) method. The proteins are treated as a dielectric continuum with a low polarizability (ϵr = 2), surrounded by a dielectric medium with high polarizability (ϵr = 80) (55). GSA, the nonpolar contribution to the solvation free energy, can be calculated through the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) shown in Equation 4,

where γ, the empirical surface tension constant, was set to 0.0072 kcal mol−1 Å−2.

Saturation Transfer Difference NMR (STD NMR)

All STD experiments were done at 15 °C using 3-mm match tubes on a Bruker Avance II+ 600 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Zurich, Switzerland). Samples were prepared in PBS, pH 7.4, containing 200 μm 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionic acid-d4 (Sigma) as an internal standard. The protein to ligand ratio in all experiments was set to 1:50. The spectra were measured at a sweep width of 16.0221 ppm and 32K data points along with water suppression using a 3–9-19 pulse sequence with gradients. For STD experiments, a pseudo two-dimensional version sequence was used. Protein resonances were suppressed by the application of a spin lock pulse with a length of 30 ms. For selective saturation, a cascade of Gaussian pulses with a length of 50 ms each and 49 db of attenuation was used with a delay of 1 ms. The duration of saturation was set to 2 s in all experiments. A total of 512 scans was acquired. The on resonance irradiation was set to −1 and 100 ppm for off resonance irradiation. STD difference spectrum resulted from the subtraction of off and on resonance spectra. Control experiments were also performed in the absence of the protein to test the effect of direct irradiation on ligand signals. Samples were prepared from stock solutions to minimize dilution effects.

Group epitope mapping by STD NMR on the G6 salt bound to GPIbα was performed to determine the ligand regions that are in close contact with the protein (56). During the experiment, the protein was selectively saturated, and the effect of this saturation was carried over to the binding ligand. As a result, the enhanced STD effect was observed for protons of the ligand that are in close contact to the protein. Therefore, this method can be used as a tool to evaluate the binding epitopes of the ligand.

To analyze the binding mode of the G6 salt with rGPIbα, STD buildup curves were obtained by collecting STD spectra at different saturation times ranging from 0.5 to 5 s. The STD intensities are obtained using Equation 5,

where I0 represents the intensity of a proton signal from the reference or off resonance spectrum, and Isat is the intensity of the proton in the corresponding STD spectrum. The STD buildup curves were fitted according to Equation 6,

where STD is the intensity of a ligand signal at saturation time t. STDmax is the maximal STD intensity, and ksat is the saturation rate constant (57). The slope of the curve at zero saturation time was calculated by multiplying STDmax and ksat. This will give a more accurate STD intensity without relaxation artifacts. The signal from the proton of the ligand with largest STD value is normalized to 100%. The relative STD effects of individual protons are normalized to that of the proton with largest STD effect to compare the effect of saturation.

Statistics

Data are represented as means ± S.E. All data were compared by the paired Student's t test. Differences were considered to be significant when p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 as indicated.

Computations

All computations were carried out on an Apple G5 Xserve cluster and Intel Dualcore2 3.40 GHz workstations. The binding free energy calculations were done on the high performance computer infrastructure of the Vlaams Supercomputer Centrum.

RESULTS

Determination of Putative Small Molecule Binding Pockets

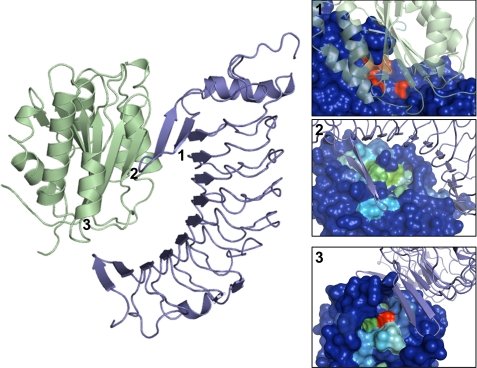

All VWF-A1 and GPIbα crystal structures available in the Protein Data Bank were superposed in PyMol to detect any crystallographic artifacts and structural variations. They aligned nicely, showing pairwise root mean square deviations of 0.1–0.5 Å (supplemental Fig. S1). The exploration of the molecular surface to locate potential small molecule binding pockets was done using 1AUQ for VWF-A1 and 1P9A for GPIbα as both structures are wild type, noncomplexed, and display a good resolution (2.3 Å for 1AUQ and 1.7 Å for 1P9A). HotPatch, PASS, and MOE Site Finder results indicated the presence of one potential pocket on GPIbα (pocket 1) and two on VWF-A1 (pockets 2 and 3) (Fig. 1). Pocket 1 consists of GPIbα Asp-83, Phe-109, Lys-133, Tyr-130, and Trp-230. Pocket 2 contains VWF-A1 Gly-567, Ile-605, and Tyr-600, and pocket 3 consists of Arg-574 and Arg-578. None of these pockets are located directly at the PPI interface, but they are in close vicinity of amino acids important for complex formation (1, 23). As such, a small molecule accommodating one of these pockets could potentially influence complex formation. Pocket stability in solution was analyzed by MD simulations. Analysis of the results show that pockets 1 (GPIbα) and 2 (VWF-A1) remained stable throughout the simulation, but pocket 3, located in the more flexible N-terminal region, appeared to switch between an open and closed state. Therefore, only pockets 1 (GPIbα) and 2 (VWF-A1) were considered as targets for small molecule docking.

FIGURE 1.

Left, VWF-A1-GPIbα complex (1SQ0) in schematic representation. VWF-A1 is colored green and GPIbα is blue. Black numbers represent the position of each pocket as it was detected by HotPatch. Right, putative pocket detection based on HotPatch output. The molecular surface of the proteins is colored according to a heat-like code indicating the probability of a surface area to be a pocket or not. Blue areas are “cold” and do not comprise the pockets, whereas the more patch-like spots are located at the other end of the color spectrum (red). In panel 1, the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex was superposed onto GPIbα to indicate the location of the pockets in the complex. Pocket 1 on GPIbα is indicated as a red area on this picture. In panels 2 and 3, the complex was superposed onto VWF-A1. Panel 2 shows pocket 2 (green area), and panel 3 displays pocket 3 (red and green area), both located on VWF-A1. Comparable results were obtained from the PASS server and the MOE Site Finder algorithm.

Selection of Small Molecules through High Throughput Molecular Docking

Commercial databases were preprocessed and merged to obtain a three-dimensional conformational database containing ∼1,500,000 compounds. The application of filters for SMPPII-like compounds (22, 42, 43) further narrowed the subset to a total of ∼1,000,000 compounds. This step was carried out because SMPPIIs tend to have slightly altered characteristics compared with drugs targeting protein-small ligand interactions (22). Using MOE, a diverse subset based on MACCS fingerprints was created, further reducing the database to a final set of ∼80,000 compounds. These compounds were docked onto the two formerly determined pockets on VWF-A1 and GPIbα using GOLD, which operates through a genetic algorithm to simulate the position of the small molecules in the pockets. Spheres (r = 15 Å) centered on the hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr-600 (VWF-A1-targeted docking), and the carboxyl carbon of Glu-128 (GPIbα-targeted docking) were used to include all residues in the binding areas important for interaction. In the case of GPIbα, the free (structure 1P9A) as well as the bound conformation (extracted from 1SQ0) were used as receptors. The 10 generated conformational docking solutions for each compound were evaluated by the three scoring functions implemented in GOLD as follows: the empirically based ChemScore (58), the force field-based GoldScore, and the knowledge-based Astex Statistic Potential (59). 40 molecules that scored well according to all three functions were retained and visually inspected to check their fitness into the pocket. 24 molecules (19 targeted against GPIbα and 5 targeted against VWF-A1) adjusted well to this criterion and were ordered for in vitro testing.

Effect of Selected Compounds on GPIbα-VWF Binding in the Ristocetin Cofactor ELISA

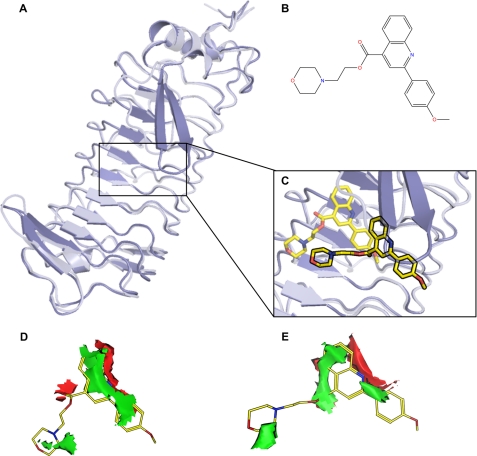

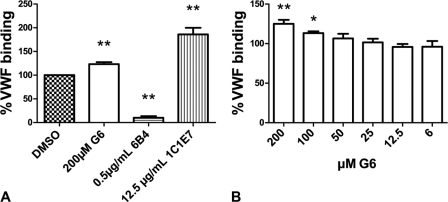

The effect of the 24 compounds on the GPIbα-VWF binding in a ristocetin cofactor ELISA was determined. No inhibitors were present; however, one compound, labeled G6 (Fig. 2B), with a mass of 393.5 Da, which was found through docking into the GPIbα pocket (Fig. 2, A and C) and was electrostatically accommodated well in the pocket (Fig. 2, D and E), dose-dependently stimulated the GPIbα-VWF-A1 binding to 123 ± 5.5% at a concentration of 200 μm with n = 4 and p < 0.01 (Fig. 3, A and B). The mAbs 6B4 and 1C1E7 were included as controls and inhibited or stimulated, respectively, VWF-GPIbα binding to 10.2 ± 3.4 and 186 ± 14% of the normal binding as expected (with p < 0.05).

FIGURE 2.

A, superposition of the conformation of GPIbα when free (light purple) and when bound to VWF-A1 (darker purple). Structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank files 1P9A and 1SQ0, respectively. B, molecular structure of G6. C, superposition of G6 docked onto free (transparent yellow) and G6 docked onto bound (yellow) GPIbα. D, electrostatic feature map calculated for free GPIbα at the position of docked G6. Red areas are favorable sites for hydrogen bond acceptors, and green areas are suitable for hydrophobic groups. E, electrostatic feature map for bound GPIbα at the position of docked G6. The same color code as in D is used here.

FIGURE 3.

A, effect of G6, the inhibitory mAb 6B4, and activating mAb 1C1E7 on GPIbα-VWF binding in the ristocetin co-factor ELISA. B, concentration-dependent stimulation of GPIb-VWF binding in the ristocetin co-factor ELISA by G6. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. (n = 6) relative to the GPIbα-VWF binding in NHP control containing 1% DMSO. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Effect of G6 on VWF-dependent Platelet Aggregation

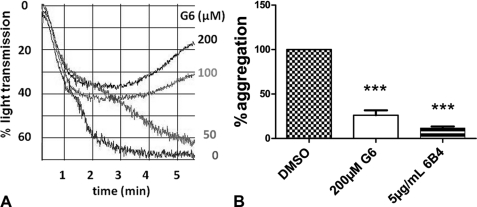

The effect of G6 on VWF-GPIbα binding was further explored in platelet aggregation. At the threshold, ristocetin concentration needed to induce complete platelet aggregation in citrated PRP, G6 surprisingly inhibited the aggregation resulting in a complete reversal of the aggregation at 10 min (representative graph in Fig. 4A). 200 μm G6 reduced platelet aggregation 6 min after addition of ristocetin to 26.2 ± 5.4% (n = 7 and p < 0.001, Fig. 4B). Also this effect was dose-dependent and disappeared around 25 μm G6 (data not shown). 5 μg/ml of the control inhibitory mAb 6B4 resulted in 10.5 ± 1.8% of the normal platelet aggregation. Inhibition of the ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation was consistent with the complete absence of ATP release in the presence of 200 μm G6 as compared with 0.51 ± 0.10 nm ATP for the DMSO control. ADP- and collagen-induced platelet aggregation was not influenced by 200 μm G6, resulting in 99.4 ± 2.6 and 93.6 ± 6.6%, respectively, of the DMSO control (with p > 0.05 and n = 3) (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

A, effect of G6 on ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation. Representative graph of the change in % light transmission in function of time after addition of ristocetin to PRP preincubated with G6 at the indicated concentration. B, aggregation responses 6 min after addition of the threshold concentration of ristocetin, expressed as percentage of the DMSO control, in the presence of either 200 μm G6 or 5 μg/ml mAb 6B4 (1% DMSO). Results are shown as means ± S.E. for three repeats with PRP from different donors. ***, p < 0.001.

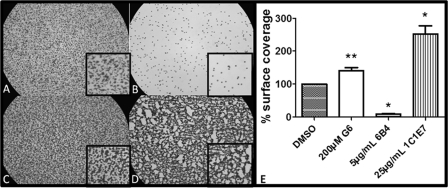

Effect of G6 on Thrombus Formation in a Single Pass Flow Chamber

Finally, the effect of G6 on VWF-dependent platelet adhesion to collagen type III was evaluated in a custom-made single pass flow chamber at a shear rate of 2600 s−1. Preincubation of whole blood from three different donors with 200 μm G6 resulted in an increased platelet deposition on collagen III to 140 ± 9.5% (n = 6 and p < 0.01; Fig. 5, C–E) of the normal (Fig. 5, A–E), whereas thrombus formation was stimulated to 252 ± 25% (n = 3 and p < 0.05) after preincubation with 25 μg/ml of the stimulatory mAb 1C1E7 (Fig. 5, D and E) and inhibited to 16.8 ± 4.3% (with n = 3 and p < 0.01) at 5 μg/ml of the inhibitory anti-GPIbα mAb 6B4 (Fig. 5, B–E).

FIGURE 5.

Shown are representative pictures of the adhesion to collagen of platelets from blood perfused at a shear rate of 2600 s−1 for 5 min at 37 °C in the presence of the respective compounds in PBS at 1% DMSO reference (A), 5 μg/ml inhibitory mAb 6B4 (B), 200 μm G6 (C), and 25 μg/ml of stimulatory mAb 1C1E7 (D). Light microscopic pictures are at ×400 magnification. E, effect of indicated compounds on platelet adhesion to collagen III at a shear rate of 2600 s−1. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of the surface coverage relative to the DMSO control with n = 6 for G6 and n = 3 for the control antibodies. Surface coverage is calculated with ImageJ. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

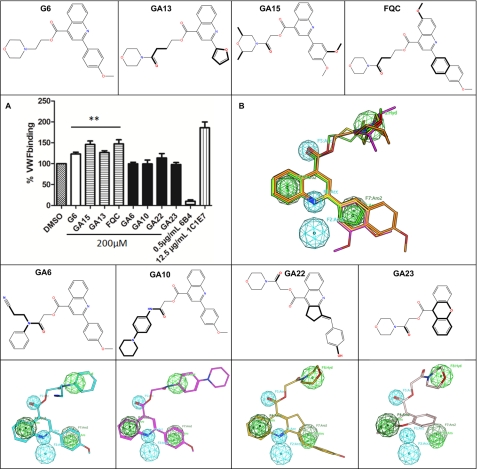

Selection of G6 Analogues through Similarity Searching

MACCS structural keys and three-point pharmacophore fingerprints were used to structurally and functionally screen the three-dimensional conformational database for compounds similar to G6. Using a Tanimoto similarity coefficient of 0.85, 28 analogues were selected. Some of these compounds such as GA13 (394.4 Da), GA15 (464.5 Da), and the in-house synthesized FQC (514.6 Da) derivative increase the binding of GPIbα-VWF to 127 ± 4.2, 146 ± 8.4, and 147 ± 9.5%, respectively, of the normal (e.g. NHP with 1% DMSO) in ristocetin cofactor ELISA (all at a concentration of 200 μm), whereas others such as GA6, GA10, GA22, and GA23 did not (Fig. 6A). This effect compares well with the 158 ± 5.3% VWF binding seen with the stimulatory mAb 1C1E7 (25 μg/ml) (47). As with G6, the activating analogues also inhibited ristocetin-induced aggregation, whereas the inactive analogues also did not affect aggregation (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Top row, molecular structures of the activating compounds G6, GA13, GA15, and FQC. In the last three compounds, structural differences with G6 are indicated as dark lines. A, effect of G6 analogues on GPIbα-VWF binding in the ristocetin co-factor ELISA. Data are expressed as means ± S.E. of the GPIbα-VWF binding relative to the NHP control containing 1% DMSO with n = 3. **, p < 0.01. B, flexible alignment of G6 (yellow), GA13 (light green), GA15 (light magenta), and FQC (orange). The features of the pharmacophore model created based on this alignment are shown as spheres. Hydrophobic/aromatic features are represented as green spheres and hydrogen acceptors and projected hydrogen bond acceptors as cyan spheres. Third row, molecular structures of GA6, GA10, GA22, and GA23, compounds without an effect on VWF-A1-GPIbα complex formation. Bottom row, flexible alignment of GA6, GA10, GA22, and GA23 with the flexible alignment of activating molecules (data not shown). The pharmacophore query based on the flexible alignment of the activating molecules (from Fig. 5B) is shown as pharmacophore feature spheres. These four last compounds do not display a good fit into the pharmacophore.

Structure-Activity Relationship through Flexible Alignment

To derive a structure-activity relationship, a flexible alignment in MOE was performed (Fig. 6B), and a pharmacophore query of the activating molecules was created. From this alignment, it was clear that the quinoline group, the ester in the linker, and the aromatic group oriented at the meta position align very well and should thus be retained in the proposed pharmacophore query. The following pharmacophore features were assigned to these functionalities as follows: an aromatic feature with projection on the benzyl of the quinoline; a hydrogen bond acceptor feature with projection on the nitrogen of the quinoline's pyridine, as well as a hydrogen bond acceptor on the carbonyl group of the ester, and an aromatic feature with projection on the aromatic meta group. The morpholine group did not align as well as the other functionalities but sufficiently enough to put a hydrophobic feature at this position.

Four other compounds (GA6, GA10, GA22, and GA23) that did not show any effect on complex formation were checked for their fitness in the pharmacophore query as well (Fig. 6). In contrast to the activating compounds, these four molecules did not correspond to the pharmacophore query; GA6 and GA10 have larger groups at the position where the aromatic feature of the morpholine group is placed, probably rendering them too bulky to fit in the pocket; GA22 lacks the aromatic functionality at the activators' methoxybenzyl location, and GA23 is lacking important functionalities, including the quinoline moiety and the methoxybenzyl group.

Binding Free Energy Calculations

Based on the docking simulation of G6 in free and VWF-A1 bound GPIbα, we suspect that G6 recognizes GPIbα at a site located below the β-switch, an event that might then be followed by a stabilization of the GPIbα structure when it binds to VWF-A1, resulting in the observed stimulation (Fig. 2, A and C). To support this hypothesis, MM/GBSA simulations were performed on the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex with G6 docked to the bound conformation of GPIbα. The binding free energy was calculated between VWF-A1 and GPIbα in the absence and presence of G6. As G6 itself was not included in the binding free energy calculations between both proteins, the measured difference in binding free energy therefore originates from changed VWF-A1-GPIbα contacts due to the presence of G6. These results, summarized in Table 1, indicated a notable improvement in the total binding free energy (ΔGsub-tot) between VWF-A1 and GPIbα when G6 is present, which is mostly caused by the increased contribution of the van der Waals interactions (ΔEvdw). In addition, a reduced standard deviation of ΔEvdw indicates that G6 might stabilize vicinal amino acids in both proteins. Thus, it can be concluded that the activating effect of G6 on the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex is mainly the result of improved van der Waals energy contacts between both proteins.

TABLE 1.

Calculated binding free energies of the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex (structure 1SQ0) in the absence and presence of G6

| Variant | ΔEeleca | ΔEvdwb (p < 0.001) | ΔGSAc | ΔGGBd | ΔGSole | ΔGElef | ΔGsub-totg (p < 0.001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SQ0 | −347.6 ± 8.7 | −76.6 ± 9.6 | −18.1 ± 0.5 | 352.8 ± 8.0 | 334.7 ± 7.9 | 5.2 ± 2.2 | −89.5 ± 8.2 |

| 1SQ0 + G6 | −375.4 ± 9.1 | −96.9 ± 5.7 | −18.5 ± 0.4 | 380.1 ± 8.4 | 361.6 ± 8.2 | 4.7 ± 2.2 | −110.7 ± 4.6 |

a Electrostatic energy change is shown as ΔEelec.

b Van der Waals energy change is shown as ΔEvdw.

c Change in the non-polar contribution to the solvation-free energy is shown as ΔGSA.

d Change in the polar contribution to the solvation-free energy is shown as ΔGGB.

e Solvation-free energy change is shown as ΔGSol.

f Total electrostatic free energy change is shown as ΔGEle = ΔEelec + ΔGGB.

g Total binding free energy change is shown as ΔGsub-tot, all in kcal/mol. All energy values are given in kcal/mol, and significant energy values are printed.

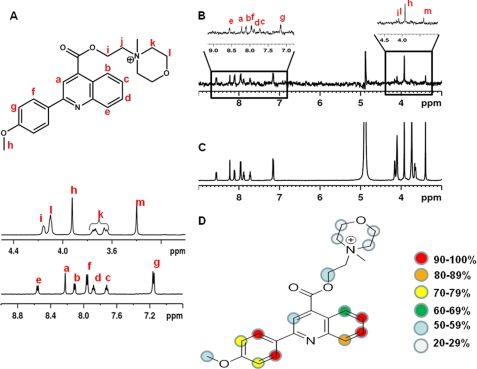

Determination of the G6-binding Protein by STD NMR

Binding of G6 to both rGPIbα and rVWF-A1 was examined by STD NMR (60). Each sample contained 10 μm of either protein domain with a 50-fold molar excess of ligand. However, only a low signal to noise ratio was observed due to the poor solubility of the G6 compound in the NMR sample conditions. To circumvent this, further STD experiments and analyses were done using the methylated salt of G6 (Fig. 7A), which has a similar effect as G6 in the ristocetin cofactor ELISA (data not shown), but it is much more soluble than G6 under the preferred NMR sample conditions. The presence of the G6 salt signals in the STD difference spectra confirmed binding of G6 to GPIbα (Fig. 7, B and C). Interactions with VWF-A1 could also be observed (data not shown), although with less pronounced STD effect.

FIGURE 7.

A, structure of the G6-salt (4-(2-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)quinoline-4-carbonyloxy)ethyl)-4-methylmorpholin-4-ium iodide) (top) with assignment of its resonances (bottom). B, right panel, STD NMR spectra showing binding of the G6 salt to rGPIbα with the reference NMR spectra in C. As indicated in the expanded detail, mainly signals from the quinoline (a–c and e) and methoxybenzene (f, g, and h) show most prominent STD effects and are therefore in close contact with GPIbα. D, binding epitopes of the G6-salt with bound GPIbα as determined by group epitope mapping STD NMR. Protons experiencing saturation effect are labeled as circles with color code representing the percentage of saturation transfer.

The results from group epitope mapping by STD NMR revealed that the G6 salt mainly bound to rGPIbα via quinoline and methoxybenzene (Fig. 7D and supplemental Fig. S2). However, the protons from both the morpholine group and the linker exhibited a small STD effect that also implies contact with rGPIbα, albeit less intimate.

DISCUSSION

Because of its special importance under high shear conditions, the VWF-A1-GPIbα interaction is considered as an interesting target for the development of new antithrombotics for patients with acute coronary syndromes, suffering from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (9), or from ischemic stroke (61). Today clinical trials are ongoing for two compounds targeting the protein partners of this complex (either VWF-A1 or GPIbα) (7–11), and as anticipated, platelet function is dose-dependently inhibited, importantly without causing bleeding effects or interference with normal hemostasis. Recently, OS1, an 11-mer cysteine-constrained cyclic peptide, has been identified, and by targeting GPIbα it inhibits agonist-induced platelet aggregation by stabilizing the β-switch forming loop region in an alternative α-helical conformation (62, 63). In addition, four other peptides able to bind to VWF-A1 and to distort its interaction with GPIbα were found by screening a peptide library, whereas subsequent modeling studies investigated the binding of these peptides to VWF-A1 in more detail (64). The large molecular weight and/or protein/peptide/nucleotide nature of all these antagonists limits their oral bio-availability. Several groups are therefore attempting to identify smaller molecules interfering with this interaction.

By targeting a putative small molecule binding pocket close to the β-switch region, we were able through high throughput molecular docking to select 24 compounds targeted against either VWF-A1 or GPIbα. This computational approach gave us the opportunity to evaluate a diverse and vast small molecule database of about 1.5 106 compounds, without having to deal with the time- and budget-bound hurdles often encountered in classical physical high throughput screening (65, 66). In vitro evaluation of selected compounds resulted in the identification of G6, a small organic molecule (393 Da) that on the one hand stimulated complex formation in a ristocetin-induced GPIbα-VWF binding ELISA but on the other hand inhibited ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation. To circumvent the artifacts that might be encountered by using ristocetin or a recombinant extracellular fragment of GPIbα, the effect of G6 was finally tested in whole blood in a flow chamber, where the VWF-GPIbα interaction is induced more physiologically by unfolding of VWF by binding to collagen and enhanced shear; G6 also stimulated the VWF-GPIbα-dependent platelet deposition.

Several docking simulations repetitively generated a consensus pose for this compound in the free and the bound conformation of GPIbα. These two poses correspond well to the calculated electrostatic feature maps for both receptor proteins (Fig. 2, D and E) and are quite similar, suggesting that GPIbα may be initially recognized by G6, followed by a stabilization of G6 bound to GPIbα upon complex formation with VWF-A1. This might result in an overall stabilization of the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex. This idea is strengthened by the fact that the conformations of the docking poses of G6 to free and VWF-A1-bound GPIbα do not differ much (Fig. 2C). To further support this hypothesis, MM/GBSA simulations were performed on the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex with and without G6 docked to GPIbα. We could observe an improvement in the total binding free energy of the complex in the presence of G6. This is mainly caused by the contribution of the van der Waals term. We suspect that the binding of G6 stabilizes the β-switch to a higher degree, because the molecule is predicted to bind in a pocket right below this region, causing VWF-A1 and GPIbα to bind more tightly. A similar mechanism is also observed in the structural binding mechanism of a few plant phytohormones such as auxin, brassinolide, and jasmonate (67–69). These molecules, nicknamed “molecular glue,” promote protein-protein interactions by creating an induced fit effect upon binding, such that the altered surfaces of their protein receptors become more susceptible toward interaction with other proteins. It is interesting to note that all these hormone reception systems, being leucine-rich repeats, are small molecule regulated receptors. GPIbα itself has eight leucine-rich repeats and is a member of this same family of proteins.

Based on structural analogues of G6 that also activate complex formation between VWF-A1 and GPIbα (Fig. 6, GA13, GA15, and FQC), a pharmacophore could be generated. As expected, compounds not influencing the VWF-GPIbα interaction (Fig. 6, GA6, GA10, GA22, and GA23) did not fit the pharmacophore.

Based on all these observations, we assume that the activator G6 presumably binds to its receptor GPIbα, mainly through hydrophobic interactions of its quinoline and methoxybenzyl moieties and through hydrogen bonds with the quinoline's nitrogen and the ester carbonyl in the linker. The presence of a hydrophobic group at the position of the morpholine moiety might also be important but is probably less determining for binding. STD NMR results were also consistent with the above findings. Group epitope mapping by STD NMR further confirmed that the quinoline and methoxybenzene of G6 salt are in close proximity to the rGPIbα compared with the morpholine group and the linker.

CONCLUSION

By using a virtual screening approach, we were able to select a small molecule that increased the GPIbα-VWF binding in ELISA and stimulated thrombus formation under flow but showed unexpectedly strongly reduced ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation. Docking results, inspection of the electrostatic feature maps of GPIbα, and a flexible alignment with other structurally related activators led to the identification of the most important functionalities of the molecule, whereas MM/GBSA studies suggested that binding of the molecule to GPIbα improves the total binding free energy of the VWF-A1-GPIbα complex. Further studies will be required to determine the exact binding position and to provide an explanation for the observed effect. Detailed structural information (e.g. a cocrystal structure) on the binding mode of G6 to GPIbα could offer possibilities for modifying the chemical structure of G6 in an attempt to develop SMPPIIs able to disrupt the VWF-A1-GPIbα interaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Vlaams Supercomputer Centrum for providing the high performance computer infrastructure for the binding free energy calculations. We also are very grateful to Biokit, S.A. (Barcelona, Spain) and A. Jacobi and E. Huizinga (Bijvoet Center for Biomolecular Research, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands) for the supply of the significant quantities of rfGPIbα and rVWF-A1 domain needed for the STD NMR studies. We thank A. Voet (Laboratory for Biomolecular Modeling, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) and K. Vanhoorelbeke (Laboratory for Thrombosis Research, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Campus Kortrijk) for suggestions and stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by Knowledge Platform Grant IOF-KP 06/001 from the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Industrial Research Fund.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- VWF

- von Willebrand factor

- GP

- glycoprotein

- SMPPII

- small molecule protein-protein interaction inhibitor

- PPI

- protein-protein interaction

- NHP

- normal human plasma

- PRP

- platelet-rich plasma

- STD

- saturation transfer difference

- MD

- molecular dynamics.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dumas J. J., Kumar R., McDonagh T., Sullivan F., Stahl M. L., Somers W. S., Mosyak L. (2004) Crystal structure of the wild-type von Willebrand factor A1-glycoprotein Ibα complex reveals conformation differences with a complex bearing von Willebrand disease mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23327–23334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Firbas C., Siller-Matula J. M., Jilma B. (2010) Targeting von Willebrand factor and platelet glycoprotein Ib receptor. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc Ther. 8, 1689–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vanhoorelbeke K., Ulrichts H., Van de Walle G., Fontayne A., Deckmyn H. (2007) Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein Ib and its antithrombotic potential. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 2684–2697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cauwenberghs N., Meiring M., Vauterin S., van Wyk V., Lamprecht S., Roodt J. P., Novák L., Harsfalvi J., Deckmyn H., Kotzé H. F. (2000) Antithrombotic effect of platelet glycoprotein Ib-blocking monoclonal antibody Fab fragments in nonhuman primates. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 1347–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu D., Meiring M., Kotze H. F., Deckmyn H., Cauwenberghs N. (2002) Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein Ib, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, or both by monoclonal antibodies prevents arterial thrombosis in baboons. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fontayne A., Meiring M., Lamprecht S., Roodt J., Demarsin E., Barbeaux P., Deckmyn H. (2008) The humanized anti-glycoprotein Ib monoclonal antibody h6B4-Fab is a potent and safe antithrombotic in a high shear arterial thrombosis model in baboons. Thromb. Haemost. 100, 670–677 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gilbert J. C., DeFeo-Fraulini T., Hutabarat R. M., Horvath C. J., Merlino P. G., Marsh H. N., Healy J. M., Boufakhreddine S., Holohan T. V., Schaub R. G. (2007) First-in-human evaluation of anti-von Willebrand factor therapeutic aptamer ARC1779 in healthy volunteers. Circulation 116, 2678–2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Knöbl P., Jilma B., Gilbert J. C., Hutabarat R. M., Wagner P. G., Jilma-Stohlawetz P. (2009) Anti-von Willebrand factor aptamer ARC1779 for refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion 49, 2181–2185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mayr F. B., Knöbl P., Jilma B., Siller-Matula J. M., Wagner P. G., Schaub R. G., Gilbert J. C., Jilma-Stohlawetz P. (2010) The aptamer ARC1779 blocks von Willebrand factor-dependent platelet function in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura ex vivo. Transfusion 50, 1079–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bartunek J., Barbato E., Holz J. B., Vercruysse K., Ulrichts H., Heyndrickx G. (2008) ALX-0081 a novel anti-thrombotic: results of a single-dose phase 1 study in healthy volunteers and further development in patients with stable angina undergoing PCI. Circulation 118, S656 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ulrichts H., Silence K., Schoolmeester A., de Jaegere P., Rossenu S., Roodt J., Priem S., Lauwereys M., Casteels P., Van Bockstaele F., Verschueren K., Stanssens P., Baumeister J., Holz J. B. (2011) Antithrombotic drug candidate ALX-0081 shows superior preclinical efficacy and safety compared with currently marketed antiplatelet drugs. Blood 118, 757–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones S., Thornton J. M. (1996) Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lo Conte L., Chothia C., Janin J. (1999) The atomic structure of protein-protein recognition sites. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 2177–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clackson T., Wells J. A. (1995) A hot spot of binding energy in a hormone-receptor interface. Science 267, 383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keskin O., Ma B., Nussinov R. (2005) Hot regions in protein-protein interactions. The organization and contribution of structurally conserved hot spot residues. J. Mol. Biol. 345, 1281–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dudkina A. S., Lindsley C. W. (2007) Small molecule protein-protein inhibitors for the p53-MDM2 interaction. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 7, 952–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vassilev L. T. (2007) MDM2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 13, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vassilev L. T., Vu B. T., Graves B., Carvajal D., Podlaski F., Filipovic Z., Kong N., Kammlott U., Lukacs C., Klein C., Fotouhi N., Liu E. A. (2004) In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science 303, 844–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oltersdorf T., Elmore S. W., Shoemaker A. R., Armstrong R. C., Augeri D. J., Belli B. A., Bruncko M., Deckwerth T. L., Dinges J., Hajduk P. J., Joseph M. K., Kitada S., Korsmeyer S. J., Kunzer A. R., Letai A., Li C., Mitten M. J., Nettesheim D. G., Ng S., Nimmer P. M., O'Connor J. M., Oleksijew A., Petros A. M., Reed J. C., Shen W., Tahir S. K., Thompson C. B., Tomaselli K. J., Wang B., Wendt M. D., Zhang H., Fesik S. W., Rosenberg S. H. (2005) An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumors. Nature 435, 677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tse C., Shoemaker A. R., Adickes J., Anderson M. G., Chen J., Jin S., Johnson E. F., Marsh K. C., Mitten M. J., Nimmer P., Roberts L., Tahir S. K., Xiao Y., Yang X., Zhang H., Fesik S., Rosenberg S. H., Elmore S. W. (2008) ABT-263. A potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer Res. 68, 3421–3428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christ F., Voet A., Marchand A., Nicolet S., Desimmie B. A., Marchand D., Bardiot D., Van der Veken N. J., Van Remoortel B., Strelkov S. V., De Maeyer M., Chaltin P., Debyser Z. (2010) Rational design of small molecule inhibitors of the LEDGF/p75-integrase interaction and HIV replication. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 442–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sperandio O., Reynès C. H., Camproux A. C., Villoutreix B. O. (2010) Rationalizing the chemical space of protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Drug Discov. Today 15, 220–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shimizu A., Matsushita T., Kondo T., Inden Y., Kojima T., Saito H., Hirai M. (2004) Identification of the amino acid residues of the platelet glycoprotein Ib (GPIb) essential for the von Willebrand factor binding by clustered charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16285–16294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., Bourne P. E. (2000) The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emsley J., Cruz M., Handin R., Liddington R. (1998) Crystal structure of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain and implications for the binding of platelet glycoprotein Ib. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10396–10401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fukuda K., Doggett T. A., Bankston L. A., Cruz M. A., Diacovo T. G., Liddington R. C. (2002) Structural basis of von Willebrand factor activation by the snake toxin botrocetin. Structure 10, 943–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Celikel R., Varughese K. I., Madhusudan, Yoshioka A., Ware J., Ruggeri Z. M. (1998) Crystal structure of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain in complex with the function blocking NMC-4 Fab. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Celikel R., Ruggeri Z. M., Varughese K. I. (2000) von Willebrand factor conformation and adhesive function is modulated by an internalized water molecule. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 881–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huizinga E. G., Tsuji S., Romijn R. A., Schiphorst M. E., de Groot P. G., Sixma J. J., Gros P. (2002) Structures of glycoprotein Ibα and its complex with von Willebrand factor A1 domain. Science 297, 1176–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maita N., Nishio K., Nishimoto E., Matsui T., Shikamoto Y., Morita T., Sadler J. E., Mizuno H. (2003) Crystal structure of von Willebrand factor A1 domain complexed with snake venom, bitiscetin. Insight into glycoprotein Ibα binding mechanism induced by snake venom proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37777–37781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fukuda K., Doggett T., Laurenzi I. J., Liddington R. C., Diacovo T. G. (2005) The snake venom protein botrocetin acts as a biological brace to promote dysfunctional platelet aggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 152–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Celikel R., McClintock R. A., Roberts J. R., Mendolicchio G. L., Ware J., Varughese K. I., Ruggeri Z. M. (2003) Modulation of α-thrombin function by distinct interactions with platelet glycoprotein Ibα. Science 301, 218–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brady G. P., Jr., Stouten P. F. (2000) Fast prediction and visualization of protein binding pockets with PASS. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 14, 383–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pettit F. K., Bare E., Tsai A., Bowie J. U. (2007) HotPatch. A statistical approach to finding biologically relevant features on protein surfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 369, 863–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A. E., Berendsen H. J. (2005) GROMACS. Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jorgensen W. L., Maxwell D. S., Tirado-Rives J. (1996) Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., Klein M. L. (1983) J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berendsen H. J., Postma J. P., Vangunsteren W. F., Dinola A., Haak J. R. (1984) Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. (1993) Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H. J., Fraaije J. G. (1997) LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comp. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halgren T. (1999) MMFF VI. MMFF94s option for energy minimization studies. J. Comp. Chem. 20, 720–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Voet A. (2010) Development of Small Molecule Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitors Targeting the HIV-1 Integrase-LEDGF/p75 Complex, Ph.D. thesis, K. U. Leuven, Leuven, Belgium [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oprea T. (2005) Cheminformatics in Drug Discovery (Mannhold R., Kubinyi H., Folkers G., eds) pp. 141–175, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vanhoorelbeke K., Cauwenberghs N., Vauterin S., Schlammadinger A., Mazurier C., Deckmyn H. (2000) A reliable and reproducible ELISA method to measure ristocetin cofactor activity of von Willebrand factor. Thromb. Haemost. 83, 107–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schumpp-Vonach B., Kresbach G., Schlaeger E. J., Steiner B. (1995) Stable expression in Chinese hamster ovary cells of a homogeneous recombinant active fragment of human platelet glycoprotein Ibα. Cytotechnology 17, 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tornai I., Arnout J., Deckmyn H., Peerlinck K., Vermylen J. (1993) A monoclonal antibody recognizes a von Willebrand factor domain within the amino-terminal portion of the subunit that modulates the function of the glycoprotein IB- and IIB/IIIA-binding domains. J. Clin. Invest. 91, 273–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ulrichts H., Harsfalvi J., Bene L., Matko J., Vermylen J., Ajzenberg N., Baruch D., Deckmyn H., Tornai I. (2004) A monoclonal antibody directed against human von Willebrand factor induces type 2B-like alterations. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2, 1622–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ulrichts H., Udvardy M., Lenting P. J., Pareyn I., Vandeputte N., Vanhoorelbeke K., Deckmyn H. (2006) Shielding of the A1 domain by the D′D3 domains of von Willebrand factor modulates its interaction with platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX-V. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4699–4707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grethe G., Moock T. (1990) Similarity searching in REACCS. A new tool for the synthetic chemist. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 363, 511–520 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hornak V., Abel R., Okur A., Strockbine B., Roitberg A., Simmerling C. (2006) Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 65, 712–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Parrinello M., Rahman A. (1981) Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 5, 7182–7190 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. (2007) Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Onufriev A., Bashford D., Case D. A. (2004) Exploring protein native states and large scale conformational changes with a modified generalized born model. Proteins 55, 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Case D. A., Cheatham T. E., 3rd, Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K. M., Jr., Onufriev A., Simmerling C., Wang B., Woods R. J. (2005) The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1668–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Honig B., Sharp K., Yang A. S. (1993) Macroscopic models of aqueous solutions: biological and chemical applications. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 1101–1109 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mayer M., Meyer B. (2001) Group epitope mapping by saturation transfer difference NMR to identify segments of a ligand in direct contact with a protein receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6108–6117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mayer M., James T. L. (2004) NMR-based characterization of phenothiazines as a RNA binding scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4453–4460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Eldridge M. D., Murray C. W., Auton T. R., Paolini G. V., Mee R. P. (1997) Empirical scoring functions. I. The development of a fast empirical scoring function to estimate the binding affinity of ligands in receptor complexes. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 11, 425–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jones G., Willett P., Glen R. C., Leach A. R., Taylor R. (1997) Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 267, 727–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mayer M., Meyer B. (1999) Characterization of ligand binding by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 38, 1784–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. De Meyer S. F., Schwarz T., Deckmyn H., Denis C. V., Nieswandt B., Stoll G., Vanhoorelbeke K., Kleinschnitz C. (2010) Binding of von Willebrand factor to collagen and glycoprotein Ibα, but not to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, contributes to ischemic stroke in mice. Brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1949–1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Benard S. A., Smith T. M., Cunningham K., Jacob J., DeSilva T., Lin L., Shaw G. D., Kriz R., Kelleher K. S. (2008) Identification of peptide antagonists to glycoprotein Ibα that selectively inhibit von Willebrand factor dependent platelet aggregation. Biochemistry 47, 4674–4682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McEwan P. A., Andrews R. K., Emsley J. (2009) Glycoprotein Ibα inhibitor complex structure reveals a combined steric and allosteric mechanism of von Willebrand factor antagonism. Blood 114, 4883–4885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Munoz Cdel C., Campbell W., Constantinescu I., Gyongyossy-Issa M. I. (2008) Rational design of antithrombotic peptides to target the von Willebrand factor (vWf)-GPIb integrin interaction. J. Mol. Model 14, 1191–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jorgensen W. L. (2004) The many roles of computation in drug discovery. Science 303, 1813–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Guido R. V., Oliva G., Andricopulo A. D. (2008) Virtual screening and its integration with modern drug design technologies. Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tan X., Calderon-Villalobos L. I., Sharon M., Zheng C., Robinson C. V., Estelle M., Zheng N. (2007) Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446, 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. She J., Han Z., Kim T. W., Wang J., Cheng W., Chang J., Shi S., Wang J., Yang M., Wang Z. Y., Chai J. (2011) Structural insight into brassinosteroid perception by BRI1. Nature 474, 472–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sheard L. B., Tan X., Mao H., Withers J., Ben-Nissan G., Hinds T. R., Kobayashi Y., Hsu F. F., Sharon M., Browse J., He S. Y., Rizo J., Howe G. A., Zheng N. (2010) Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature 468, 400–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.