Background: DNA damage triggers a complex signaling cascade that remains incompletely understood.

Results: The essential chaperone Hsp90α is phosphorylated by DNA damage signaling kinases and accumulates at DNA damage sites.

Conclusion: Hsp90α is directly involved in DNA repair.

Significance: Our results provide an explanation for the radiosensitizing effect of Hsp90 inhibitors and identify phosphorylated Hsp90α as a potential biomarker for genetic instability.

Keywords: DNA Damage Response, DNA Repair, Heat Shock Protein, Phosphorylation, Radiation Biology, Hsp90

Abstract

DNA damage triggers a complex signaling cascade involving a multitude of phosphorylation events. We found that the threonine 7 (Thr-7) residue of heat shock protein 90α (Hsp90α) was phosphorylated immediately after DNA damage. The phosphorylated Hsp90α then accumulated at sites of DNA double strand breaks and formed repair foci with slow kinetics, matching the repair kinetics of complex DNA damage. The phosphorylation of Hsp90α was dependent on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-like kinases, including the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) in particular. DNA-PK plays an essential role in the repair of DNA double strand breaks by nonhomologous end-joining and in the signaling of DNA damage. It is also present in the cytoplasm of the cell and has been suggested to play a role in cytoplasmic signaling pathways. Using stabilized double-stranded DNA molecules to activate DNA-PK, we showed that an active DNA-PK complex could be assembled in the cytoplasm, resulting in phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic pool of Hsp90α. In vivo, reverse phase protein array data for tumors revealed that basal levels of Thr-7-phosphorylated Hsp90α were correlated with phosphorylated histone H2AX levels. The Thr-7 phosphorylation of the ubiquitously produced and secreted Hsp90α may therefore serve as a surrogate biomarker of DNA damage. These findings shed light on the interplay between central DNA repair enzymes and an essential molecular chaperone.

Introduction

DNA double strand breaks (DSBs)2 are thought to be among the most deleterious lesions occurring in cells. Several cellular mechanisms for repairing such damage have thus evolved (1–4). The members of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase protein kinase-like (PIKK) family, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR), and the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), serve as damage sensors. They phosphorylate a multitude of proteins, initiating a complex signaling cascade resulting in DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, or cell death (5, 6). PIKKs preferentially phosphorylate serine or threonine residues that are followed by a glutamine residue (7).

In mammalian cells, nonhomologous end-joining is the principal pathway for the repair of double strand breaks (DSBs). DNA-PK is the key enzyme of this pathway. It recognizes and binds to DSBs, regulates the correct alignment of the DNA ends, and controls the access of other DNA repair factors to the damaged DNA (8). Recent findings suggest that, in addition to its well established role in DNA repair in the nucleus, DNA-PK may be involved in the phosphorylation of cytoplasmic targets involved in cellular signaling pathways, such as UV-induced translational reprogramming (9), NFκB activation (10, 11), or the regulation of Akt/PKB (12). The implications of these functions are not yet well understood.

Heat shock proteins are functionally related molecular chaperones. They are involved in the post-translational folding, stability, activation, and maturation of proteins. Hsp90α is a ubiquitous heat shock protein accounting for 1–2% of the total protein present in the cell (13). Hsp90α has about 200 client proteins, including protein kinases, ribonucleoproteins, steroid hormone receptors, chromatin remodeling factors, and transcription factors (14). Cancer cells seem to have a special requirement for Hsp90α, as it chaperones many oncoproteins and other proteins contributing to malignancy in cancer, making Hsp90α a potential target for cancer treatment (14, 15). Hsp90α inhibitors have been reported to compromise the DNA damage response after irradiation, but the exact mechanisms involved remain unclear (16–18).

We used short (32 bp) stabilized double-stranded DNA molecules (Dbait 32Hc) to induce a DSB-specific damage response in cells without the induction of chromosomal damage (19). It has been shown that in the course of this response, which is strictly dependent on DNA-PK, several nuclear DNA-PK targets (p53, Rpa32, and H2AX) are strongly phosphorylated. The Dbait 32Hc-induced signal has the advantage of inducing a very stable response that persists for several days (19). We made use of this property to investigate novel DNA-PK targets and the cytoplasmic role of DNA-PK.

In our search for new proteins phosphorylated at (S/T)Q motifs in response to DNA damage, we identified proteins cross-reacting with an antibody raised against a synthetic DNA-PKcs peptide, in which Thr-2609 was phosphorylated. The predominant protein recognized by this antibody in cells exposed to DNA-damaging agents was Hsp90α. We mapped the site of Hsp90α phosphorylation to the threonine 7 (Thr-7) and showed that this residue was phosphorylated by DNA-PK and other PIKK family members. We also demonstrated that the phosphorylated form of Hsp90α accumulated at the site of DNA damage, where it seemed to be important for the maintenance of phosphorylated histone H2AX. These results suggest that Hsp90α is directly regulated by DNA damage signaling factors and involved in the DNA damage response.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Irradiation, Reagents, Dbait Molecules, and Transfection

Studies of cells in culture were performed with the following: SV40-transformed MRC-5 (human fibroblasts, ATCC CCL-171); HEp-2 (human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, ATCC CCL-23); HeLa S3 (human cervix carcinoma, ATCC CCL-2.2); human glioblastomas U87 (ATCC HTB-14); U87 Luc (kindly provided by JL. Coll, Université Joseph Fourier, Grenoble, France); FOG and U251 (both kindly provided by P. Verrelle, Centre Jean Perrin, Clermont-Ferrand, France); U118 (ATCC HTB-15); colorectal carcinomas HCT116 (ATCC CCL-247) and HT29 (ATCC HTB-38); ATM-defective AT5BI cells (human fibroblasts (20)); and M059K and DNA-PK-defective M059J (human glioblastoma (21)) cells. Cells were grown at 37 °C, as monolayers, in complete DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate and antibiotics (100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 μg/ml penicillin), under conditions of 100% humidity, in an atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2. For BRCA2 HeLa SilenciX and Control HeLa SilenciX cells (both from Tebu-bio, Le Perray en Yvelines, France), the growth medium was supplemented with 125 μg/ml hygromycin B. For rat glioblastoma C6, RG2, and F98 cells (kindly provided by J. L. Coll) (22), we added 1% nonessential amino acids to the growth medium. Human glioblastoma CB193, T98G, SF763, and SF767 cells were kindly provided by P. Verrelle and grown as described previously (23). SK-28 (human melanoma (68)) cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics. LU1205 (human melanoma) cells were grown in MCDB medium (Sigma) supplemented with 4% heat-inactivated FCS and 1% glutamine and antibiotics. Irradiation was performed with the 137Cs unit of IBL-637 (ORIS, France) at room temperature (RT). Dbait molecules were produced by Eurogentec, as described previously (24). The sequence of Dbait 32Hc is 5′-GCTGTGCCCACAACCCAGCAAACAAGCCTAGA-(H)-TCTAGGCTTGTTTGCTGGGTTGTGGGCACAGC-3′, where H is a hexaethylene glycol linker. Cells were transfected with Dbait molecules in the presence of linear 11-kDa polyethyleneimine (PEI) (Polyplus-Transfection, Illkirch, France), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Unless otherwise indicated, cells were transfected at 80% confluence, with 2 μg of Dbait in 1.3 ml of culture medium without FCS (in 60-mm diameter plates) for 5 h. They were then left to recover for 1 h in medium supplemented with FCS. siRNA specific for Hsp90α (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool, J-005186-06 to -09, Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) and control siRNA (ON-TARGETplus Nontargeting pool, Dharmacon) were then used to transfect the cells in the presence of DharmaFECT (Dharmacon), according to the manufacturer's instructions. KU-55933 was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX), and NU7026 and wortmannin were obtained from Sigma.

Antibodies and Immunological Techniques

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the following targets were used: DNA-PKcs-S2056P (generously provided by David. J. Chen, Dept. of Radiation Oncology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas); Hsp90α-Thr(P)-5/7 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); Hsp90α (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); MDC1 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX); and 53BP1 (Cell Signaling Technology). The following mouse monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-γ-H2AX clone JBW301 (Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-β-actin clone AC-15 (Sigma), anti-Hsp90α (StressMarq Biosciences, Victoria, Canada), anti-DNA-PKcs clone 18–2 (Abcam), and anti-DNA-PKcs-T2609P clone 10B1 (referred to in the text as “a-TQ-P”, Abcam). For immunofluorescence staining, cells were processed as described previously (19). Hair samples were prepared for immunohistochemistry as described previously (25). Microscopy was performed with the Leica SP5 confocal system, attached to a DMI6000 stand, with a 63×/1.4 or 40×/1.25 oil immersion objective. Images were processed with ImageJ software (rsb.info.nih.gov), with the LOCI bioformat plug-in. Subcellular colocalization was quantified with ImageJ, using the JACoP plug-in. Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated after applying Costes' automatic threshold, as described previously (26). Foci were counted by eye. For all quantifications, we analyzed at least 200 cells for each set of conditions. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the protein-G immunoprecipitation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). The precipitates were denatured by boiling in Laemmli buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE in NuPAGE BisTris 4–12% polyacrylamide gradient minigels (Invitrogen). Gels were fixed in 50% ethanol and 10% acetic acid and stained with ProQ Diamond (Invitrogen), Sypro Ruby (Invitrogen), and SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The stained gels were imaged with a Typhoon Trio scanner (GE Healthcare) and analyzed with ImageQuant software. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (19). For the analysis of cell response kinetics, the cells were lysed by scraping into Laemmli buffer and boiling for 10 min. The resulting lysates were then centrifuged, and protein levels were normalized with the BCA protein assay kit. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE in 12 or 5% polyacrylamide (35.5 acrylamide, 1 bisacrylamide) gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked by incubation with Odyssey buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) for 1 h, and hybridized overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody diluted in Odyssey buffer. Western blots were probed with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 680 (Invitrogen) or IRdye 800 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA). The blots were imaged and quantified with the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences) and Odyssey software. For the analysis of secreted protein, cells were incubated for 24 h without serum; the supernatant was then recovered and concentrated 50× in Amicon Ultra-0.5 filter tubes (Millipore) before processing for immunoblotting.

Trypsin Digestion and Mass Spectrometry

In-gel digestion was performed, according to standard protocols. Briefly, the gel slices were washed, and the proteins were reduced with 10 mm DTT (Sigma) and alkylated with 55 mm iodoacetamide (Sigma). The gel pieces were washed with 100% acetonitrile and incubated overnight with trypsin (Roche Diagnostics) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate at 30 °C. Probes were used directly for nano-liquid chromatography-coupled tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) for protein identification. Each sample was concentrated and then separated on a C18 reverse phase column, with a linear acetonitrile gradient (UltiMate 3000 System, Dionex, and column 75 μm inner diameter × 15 cm, packed with C18 PepMapTM, 3 μm, 100 Å; LC Packings) before MS and MS/MS. Spectra were recorded on an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron) and analyzed with MascotTM (Matrix Science, London, UK) and Phenyx (Geneva Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland) software, using the “Homo sapiens” data base of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, 2009, 07 03, 226,303 protein entries). All data were validated with myProMS (27).

Cell Proliferation Assay and Alkaline Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis (“Comet Assay”)

For cell proliferation analysis, cells were seeded in 24-well plates, incubated for 48 h, and transfected with siRNA. The cells were then used to seed additional plates 48 h after transfection, and they were irradiated 69 h after transfection. The cells were fixed, 10 days later, by incubation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at RT, washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, washed, and incubated for 10 min with To-Pro-3 (Invitrogen) to stain the cell nuclei. To-Pro-3 was quantified with the Odyssey infrared imaging system. Single cell gel electrophoresis was carried out as described previously (19). Slides with cells suspended in 0.5% low melting point agarose in DMEM were irradiated or left no irradiated and were then incubated in DMEM growth medium under cell growth conditions for various periods of time after irradiation. The “comets” were analyzed with Comet Assay IV software (Perceptive Instruments, Haverhill, UK).

DNA-PK Activity and Autophosphorylation Assay

DNA-PK activity was monitored with the SignaTECT DNA-dependent protein kinase assay system (Promega, Lyon, France) as described previously (19). For DNA-PK autophosphorylation analysis, we incubated 50–200 units of purified DNA-PK (Promega) with 0.1 mm ATP, 1 μm [γ-32P]ATP, 10 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.1 μg/μl Dbait or 0.05 μg/μl thymus DNA (Promega) in 20 mm KCl, 0.2 mm DTT, 10 mm HEPES/KOH, pH 7.5, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.05 mm EGTA, 0.025 mm EDTA/KOH, pH 7.5. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at 30 °C, and the reaction was stopped by adding 2× SDS sample buffer. The denatured proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE in a 5% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide, 35.5:1) gel. The gel was dried, and its storage phosphor autoradiograph was scanned with a Storm 820 scanner (GE Healthcare) and analyzed with ImageQuant (GE Healthcare) software.

Xenografted Tumors in Mice

Human glioblastoma (U87, U87IC, CB193, T98G, SF763, FOG, SF767, M059K, U118, and U251), rat glioblastoma (C6, RG2, and F98), and human colon carcinoma (HCT116 and HT29) tumors were obtained by injecting 107 tumor cells into the flank of adult female nude mice (Janvier, Le Genest St. Isle, France). Human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HEp-2) and melanoma (SK-28, LU1205) xenograft tumors were obtained by injecting 106 or 4 × 106 tumor cells, respectively, into the mice. Fragments of ODA4GEN, TG14-CHA, GBM14-RAV, TG1-HAM, and TG17-GIR human glioma tumors and BC173BAS breast carcinoma were obtained from the preclinical investigation laboratory of Institut Curie (Laboratoire d'Investigation Préclinique, Paris, France) and xenografted into mice, as described elsewhere (28, 29). The housing of the animals has been described elsewhere (24), and the Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation approved all experiments. The animals were killed humanely when tumor volume reached 2000 mm3, and the tumors were frozen in liquid nitrogen. For the preparation of protein extracts, tumor samples were weighed and lysed in a Precellys 24 tissue homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) four times for 30 s at 6000 rpm, with Precellys CK28 beads (Bertin Technologies) in 12 μl/mg Laemmli buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 5% glycerol) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics), 2.5 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 10 mm NaF, and 2 mm Na3VO4. The samples were boiled for 15 min and centrifuged, and the supernatant was recovered without the lipid fraction. Protein concentration was determined with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce).

Reverse Phase Protein Array

Samples were deposited onto nitrocellulose-covered slides (Schott Nexterion NC-C, Jena, Germany) with a dedicated arrayer (2470 Arrayer, Aushon Biosystems, Billerica, MA). Five serial dilutions, ranging from 2 to 0.125 mg/ml, and four technical replicates per dilution were used for each sample. Detection was carried out with specific antibodies or without primary antibody (negative control), with Autostainer Plus (Dako, Trappes, France). Briefly, slides were incubated with avidin, biotin, and peroxidase blocking reagents (Dako) and then saturated with TBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% BSA (TBST-BSA). The slides were then probed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in TBST-BSA. The arrays were washed in TBST and then probed with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Newmarket, UK) diluted in TBST-BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The signal was amplified by incubating the slides with amplification reagent (Bio-Rad) for 15 min at room temperature. The arrays were then washed with TBST, probed with Cy5-streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in TBST-BSA for 1 h at RT, and washed again in TBST. Total protein staining was achieved by incubating the arrays for 15 min in 7% acetic acid and 10% methanol, rinsing twice in water, incubating for 10 min in Sypro Ruby (Invitrogen), and rinsing again. The processed slides were dried by centrifugation and scanned with a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Spot intensity was determined with MicroVigene software (VigeneTech Inc., Carlisle, MA). Quantification of the data was achieved with SuperCurve (30), and the data were normalized against negative control slides and Sypro Ruby slides. The correlation between the levels of different proteins was analyzed by calculating Pearson's correlation coefficient and significance, with Origin 8.0 software (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA).

RESULTS

Thr-7 Residue of Hsp90α Is Phosphorylated in Response to DNA Damage

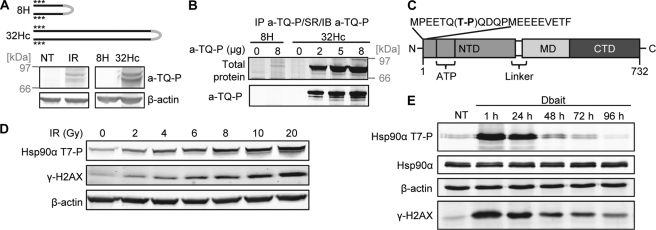

With the aim of identifying new proteins phosphorylated in response to DNA damage at PIKK target consensus sites ((S/T)Q), we characterized the products of cross-reaction with an antibody (hereafter referred to as a-TQ-P) against a synthetic DNA-PKcs peptide phosphorylated at Thr-2609. A DNA damage response was induced in MRC-5 cells (transformed human fibroblasts) with ionizing radiation (IR) or the short stabilized double-stranded DNA molecule Dbait 32Hc (Fig. 1A) (19). The a-TQ-P antibody detected no protein in untreated cells but at least six proteins with molecular weights different from that of DNA-PK in whole cell lysates from MRC-5 cells that had been irradiated or transfected with Dbait 32Hc (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S1). The major protein recognized by the antibody had a molecular mass of ∼90 kDa (Fig. 1, A and B). Immunoprecipitation, followed by immunoblotting with a-TQ-P, confirmed that the antibody directly recognized these proteins (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1). As this antibody is directed against the Thr-2609 autophosphorylation site of DNA-PK, it should preferentially recognize epitopes corresponding to the consensus target site of DNA-PK or other PIKK family members. With the aim of identifying these potential PI3K downstream targets, the immunoprecipitated proteins were digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC/MS/MS. The proteins phosphorylated in response to DNA damage were as follows: (i) nucleoprotein TPR, a component of the nuclear pore complex involved in nuclear protein export, mitotic spindle checkpoint, and heterochromatin distribution, which has been shown to be phosphorylated in response to IR (6, 31); (ii) deleted in breast cancer 1 (DBC1), an inhibitor of protein deacetylases involved in apoptosis, histone modification, and cell proliferation (32); and (iii) the 37/67-kDa laminin receptor (37/67-kDa LR, also known as 40 S ribosomal protein SA), which has been implicated in various processes, including the binding of viruses to cells and tumor cell metastasis (33). We also found that three members of the chaperone and ubiquitination system were phosphorylated: Hsp105, Hsp90α, and stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 (STIP1). The major band at ∼90 kDa corresponded to Hsp90α. For identification of the site of Hsp90α phosphorylation in response to DNA damage, we immunoprecipitated Hsp90α from Dbait 32Hc-treated MRC-5 cells with the a-TQ-P antibody, digested it with chymotrypsin, and analyzed the resulting peptides by LC/MS/MS. The spectrum obtained clearly showed that the Thr-7 residue in the conserved N terminus of the protein was phosphorylated (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 1.

Hsp90α phosphorylation at Thr-7 in response to DNA damage. A, top panel, schematic diagram of the structures of the DSB-mimicking 32Hc and the short control 8H. Two complementary DNA strands of 8 bp (8H) or 32 bp (32Hc) are tethered by a hexaethylene glycol linker (gray), and three phosphorothioate nucleotides (asterisks) are incorporated at both the 5′ and 3′ ends to protect the molecule from nucleases. Lower panel, MRC-5 cells were left untreated (NT), irradiated, or transfected with Dbait 32Hc or 8H and lysed 1 h after the end of the treatment. The extracts were immunoblotted and probed with a-TQ-P and β-actin antibodies. B, lysates of MRC-5 cells transfected with Dbait 32Hc or 8H were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with the a-TQ-P antibody. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained for total protein with SYPRO Ruby (SR) or immunoblotted (IB) for Hsp90α. C, domain structure of Hsp90α. The phosphorylated Thr-7 in the N terminus of the protein is shown in bold typeface. NTD, N-terminal domain; MD, middle domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; ATP, ATP-binding site. D, MRC-5 cells were irradiated with the indicated doses of γ-irradiation and lysed 30 min after irradiation. The extracts were immunoblotted and probed for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7), γ-H2AX, and β-actin. E, MRC-5 cells were transfected or not transfected (NT) with Dbait 32Hc and lysed at the indicated time points after transfection. The extracts were treated as in D. Total Hsp90α was detected on a separate membrane.

Twenty years ago, Lees-Miller and Anderson (34) observed, in an in vitro assay with purified DNA-PK, that Hsp90α was phosphorylated at the threonine residues in positions 5 and 7, with the enzyme displaying a preference for Thr-7. This observation and its relevance have not been investigated further. Using a polyclonal antibody directed against these phosphorylated sites, we confirmed that Hsp90α was phosphorylated in response to DNA damage. The use of this antibody for immunoprecipitation from Dbait 32Hc-treated MRC-5 cells, followed by chymotrypsin digestion and LC/MS/MS analysis, revealed that the Thr-7 residue of Hsp90α was phosphorylated in response to DNA damage, whereas the Thr-5 residue was not. This suggests that the phospho-specific antibody recognizes Hsp90α phosphorylated at Thr-7. The specificity of the antibody was further confirmed by Western blotting and immunoprecipitation (supplemental Fig. S3). Hsp90α phosphorylation in response to γ-irradiation was dose-dependent and correlated with phosphorylation of the Ser-136 residue of a known target of PIKK, the histone H2AX (γ-H2AX) (Fig. 1D).

Dbait 32Hc induced very persistent Hsp90α phosphorylation, with the phosphorylation signal remaining unchanged for 24 h and not returning to basal levels until 3 days after transfection (Fig. 1E). Total Hsp90α levels did not change over time. Two bands were observed for total Hsp90α, potentially corresponding to the two different splicing isoforms of Hsp90α (HSP90AA1-1 and HSP90AA1-2), both of which contain the phosphorylation motif. These two bands displayed similar levels of phosphorylation in response to Dbait 32Hc or irradiation (Fig. 1E).

Multiple Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-related Kinases Phosphorylate Hsp90α in Cells

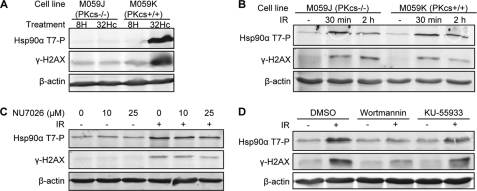

The PIKK family members ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK have overlapping substrate specificities in vitro and often phosphorylate the same substrates in vivo (7). We previously showed that the short double-stranded Dbait 32Hc molecules activate DNA-PK specifically, leading to the phosphorylation of DNA-PK downstream targets without the activation of ATM (19). In response to Dbait 32Hc, Hsp90α was strongly phosphorylated at Thr-7 in DNA-PK-proficient M059K human glioma cells, but this response was completely abolished in the DNA-PK-deficient counterpart of these cells, M059J cells (Fig. 2A), confirming that DNA-PK can phosphorylate Hsp90α in cells. In contrast to Dbait 32Hc treatment, IR treatment induces a multitude of different types of damage and the activation of various DNA damage-signaling kinases. The phosphorylation of Hsp90α induced by IR was similar in M059J and M059K cells, suggesting that multiple PIKKs may phosphorylate Hsp90α at Thr-7 (Fig. 2B). We investigated this issue further, by treating MRC-5 cells with specific inhibitors of DNA-PK (NU7026), ATM (KU-55933), or all PIKKs (wortmannin) before irradiation (Fig. 2, C and D). NU7026 treatment had little effect on IR-induced Hsp90α phosphorylation (Fig. 2C), confirming that DNA-PK is not the only PIKK capable of phosphorylating Hsp90α in cells. Consistent with this finding, Hsp90α phosphorylation was only slightly inhibited by the ATM inhibitor KU-55933 but was completely abolished by wortmannin (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Involvement of multiple PIKKs in the phosphorylation of Hsp90α at Thr-7. A, M059K and DNA-PK-deficient M059J cells were transfected with Dbait 32Hc or 8H and lysed 1 h after transfection. The extracts were immunoblotted and probed for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7), γ-H2AX, and β-actin. B, M059K and M059J cells were γ-irradiated (IR) with 10 Gy and lysed at the indicated times after irradiation. The extracts were processed as in A. C, MRC-5 cells were treated 1 h before 10 Gy irradiation (IR) with the indicated concentrations of the DNA-PK inhibitor NU7026. The cells were incubated for 30 min with NU7026 after irradiation and then lysed, and extracts were immunoblotted as in A. D, MRC-5 cells were treated 1 h before irradiation (IR) with 20 μm of the PIKK inhibitor wortmannin, 10 μm of the ATM-inhibitor KU-55933, or vehicle (DMSO). The cells were irradiated (10 Gy), incubated for further 30 min with the inhibitor, and then lysed, and extracts were processed as in A.

Thr-7-phosphorylated Hsp90α Is Recruited to Sites of DSBs with Slow Kinetics

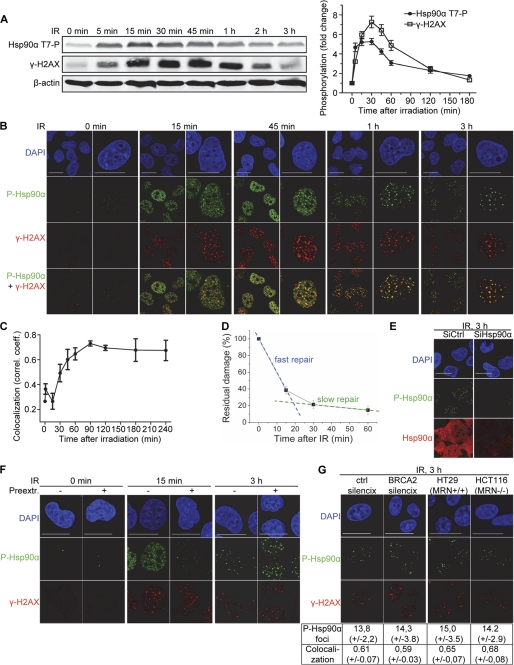

In response to irradiation, many phosphorylated proteins involved in DNA damage signaling or repair accumulate at the site of the break and form foci (35). IR induced rapid Hsp90α phosphorylation, with similar kinetics to the phosphorylation of H2AX (Fig. 3A). However, unlike γ-H2AX, which rapidly forms foci on damaged DNA, Thr-7-phosphorylated Hsp90α was initially diffusely distributed throughout the nucleus. The small number of P-Hsp90α foci detected at early time points was not colocalized with γ-H2AX (Fig. 3, B and C). About 45 min after irradiation, P-Hsp90α began to colocalize with γ-H2AX in large repair foci at damage sites (Fig. 3, B and C). By this time point, about 80% of the damage had been repaired, as demonstrated in an alkaline comet assay (Fig. 3D). Most of the remaining damage at this time point concerns complex DNA damage or damage to regions of complex chromatin (36), suggesting that P-Hsp90α may play a specific role in the repair of this type of damage. Extraction in mild detergent before the fixation of irradiated cells at 15 min removed the immediately phosphorylated pool of Hsp90α, indicating a lack of association with chromatin (Fig. 3E). By contrast, the Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) pool colocalized with γ-H2AX at later time points after irradiation could not be removed by this prior extraction treatment and was therefore stably associated with the ionizing radiation-induced foci at the site of DNA damage at these times (Fig. 3E). The IR-induced Thr-7-phosphorylated Hsp90α signal was abolished in cells treated with siRNA against Hsp90α, confirming that the foci recognized by the anti-Hsp90α (Thr-7) antibody actually contained phosphorylated Hsp90α (Fig. 3F).

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment of phosphorylated Hsp90α to DNA damage sites. A, MRC-5 cells were irradiated (IR) with 10 Gy and lysed at the indicated time points after irradiation. The extracts were subjected to Western blotting, and the blots were probed with antibodies against Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7), γ-H2AX, and β-actin. The graph shows the quantification of H2AX and Hsp90α phosphorylation with standard deviations from three Western blot analyses. B, MRC-5 cells were irradiated with 10 Gy, fixed at the indicated times after IR, and double-immunostained with anti-Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) (green) and anti-γ-H2AX (red) antibodies. C, colocalization of phosphorylated H2AX and Hsp90α at the indicated times after IR was quantified by measuring Pearson correlation coefficient (correl. coeff.) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are the means ± S.D. >200 cells per time point and two independent experiments. D, cells were irradiated, and DNA damage was quantified at the indicated times by alkaline comet assay. The data shown are the means of median comet tail moments and standard deviations from three independent experiments and are presented as a percentage of initial radiation-induced damage (black squares). Fast and slow repair components are highlighted in blue and green, respectively. E, MRC-5 cells were irradiated with 10 Gy γ-irradiation and fixed at the indicated times after irradiation. Where indicated, cells were extracted with Triton X-100 before fixation. Cells were double-immunostained for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) (green) and γ-H2AX (red). F, MRC-5 cells were transfected with 100 nm siRNA against Hsp90α or control siRNA, irradiated 96 h later with 10 Gy γ-irradiation, fixed 3 h after IR, and double-immunostained for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) (green) and Hsp90α (red). G, MRN-defective HCT116, MRN-proficient HT29 cells, and HeLa cells silenced with shRNA for BRCA2 (BRCA2 SilenciX) or control shRNA (ctrl SilenciX) were irradiated with 10 Gy, fixed 3 h after IR, and double-immunostained with anti-Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) (green) and anti-γ-H2AX (red) antibodies. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. The data show the average foci number with standard deviation as quantified from >200 cells in two independent experiments. Colocalization between Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) and γ-H2AX was quantified as in C.

Hsp90 has been reported to interact with BRCA2 (37) and the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex (16). We therefore hypothesized that Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) might be present at damage sites, due to its association with these DNA repair components. We tested this hypothesis by monitoring the formation of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) foci in mutant cells lacking BRCA2 or MRN. We detected irradiation-induced foci in HCT116 colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 3G), which lack MRN complexes due to a mismatch mutation in the MRE11 gene (38, 39). The number of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) foci and their extent of colocalization with γ-H2AX were similar to those observed in MRN-proficient HT29 (38) colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, HeLa cells with stable silencing of BRCA2 displayed no impairment of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) foci formation in response to IR, as shown by comparison with the control (Fig. 3G). Thus, the recruitment of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) to DNA breaks is not exclusively dependent on its interaction with BRCA2 or MRN complexes.

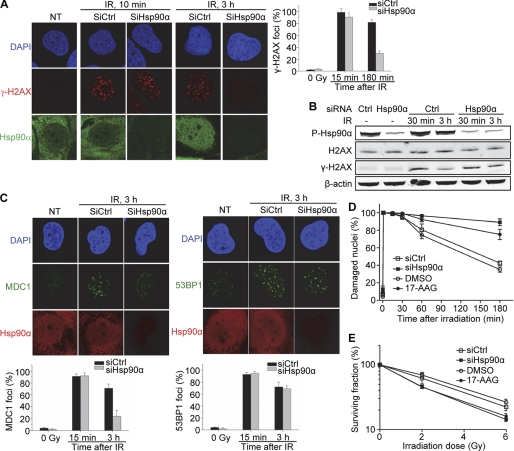

Hsp90α Is Required for the Maintenance of γ-H2AX Foci and Efficient DNA Repair

We investigated the effect of the absence of Hsp90α on the organization of DNA repair foci. Shortly after irradiation, the γ-H2AX foci in Hsp90α-silenced MRC-5 cells were identical to those in nonsilenced cells (Fig. 4A). However, 3 h after irradiation, γ-H2AX was diffusely distributed in Hsp90α-silenced cells, with no detectable foci, whereas numerous foci remained in the nonsilenced control (Fig. 4A). This suggests that Hsp90α may be important for the maintenance of γ-H2AX foci but not for their formation. Immunoblotting showed that Hsp90α silencing had no effect on total H2AX levels (Fig. 4B). The γ-H2AX signal decreased due to damage repair in the nonsilenced cells but remained constant 3 h after irradiation in the Hsp90α-silenced cells. Thus, the loss of local foci of H2AX phosphorylation was not due to dephosphorylation. Moreover, the persistence of γ-H2AX suggests that the lack of Hsp90α prevents efficient DNA repair, as already demonstrated with Hsp90 inhibitors (16).

FIGURE 4.

Impact of Hsp90α silencing on DNA repair and the organization of repair foci. A–E, MRC-5 cells were transfected with 100 nm siRNA against Hsp90α (SiHsp90α) or equal amounts of control siRNA (SiCtrl) and irradiated with 10 Gy γ-irradiation when indicated. They were then left to grow for 96 h before treatment. A, cells were fixed 3 h after IR (10 Gy) and double-immunostained for γ-H2AX (red) and Hsp90α (green). The bar chart gives the percentage of cells with more than 20 H2AX foci, with a standard deviation for each set of conditions in three independent experiments. B, cells were lysed at the indicated times after IR, and the extracts were immunoblotted and probed for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7), γ-H2AX, and β-actin. H2AX was detected on a separate membrane. C, cells were fixed 3 h after IR (10 Gy) and double-immunostained for Hsp90α (red) and MDC1 (green) (left panel) or Hsp90α (red) and 53BP1 (green) (right panel). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. The bar chart gives the percentage of cells with more than 20 foci as in A. D and E, where indicated, cells were treated for 1 h with 250 nm 17-AAG or with vehicle (DMSO) before irradiation. D, cells were irradiated (10 Gy), and damaged nuclei were quantified by the alkaline comet assay at the indicated times. Nuclei were considered damaged when the tail moment exceeded 95% of the values for the nonirradiated control. The data shown are means from three independent experiments with standard deviations. E, cells were γ-irradiated with the indicated doses and quantified 10 days later, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data shown are means from three independent experiments with standard deviations.

We investigated the effect of inhibiting the ATPase activity of Hsp90 with the geldanamycin derivative 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) on the protein phosphorylation and focus formation in response to irradiation. Surprisingly, 17-AAG did not have the same effect as Hsp90α silencing. In cells previously treated with 17-AAG, Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) formed foci that colocalized with γ-H2AX repair foci in response to IR and were maintained for even longer periods than in nontreated cells (supplemental Fig. S4). As reported previously (16), the longer persistence of γ-H2AX foci in response to 17-AAG treatment reflects the repair defect in treated cells. These results suggest that neither the phosphorylation nor the recruitment of Hsp90α is abolished by the inhibition of Hsp90 by 17-AAG. Instead, a nonfunctional form is recruited that is unable to carry out DNA repair functions.

MDC1 (Mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1) binds directly to γ-H2AX (40). We therefore investigated its redistribution in response to irradiation in the absence of Hsp90α. Consistent with the diffuse distribution of γ-H2AX observed in Hsp90α-silenced cells, the focal concentration of MDC1 was impaired 3 h after irradiation. By contrast, neither focus formation nor the maintenance of 53BP1, which binds to methylated histone H3 and H4 residues but not to γ-H2AX (41), was impaired by Hsp90α silencing (Fig. 4C). Thus, Hsp90α may act specifically on γ-H2AX and its partners. This led us to analyze DNA repair kinetics following irradiation in Hsp90α-silenced cells, in the alkaline comet assay. Repair was found to be impaired in cells lacking Hsp90α, particularly for DNA lesions persisting for more than 3 h after irradiation (Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained when Hsp90 ATPase activity was inhibited by treating the cells with 17-AAG (Fig. 4D). Consistently, survival analysis showed that siHsp90α silencing led to radiosensitization (Fig. 4E). The observed effect on survival was mild, with a decrease in LD50 from 2.8 Gy in control cells to 1.8 Gy in Hsp90α-silenced cells. However, the magnitude of this effect was similar to that for the Hsp90 inhibitor 17-AAG, which decreased the LD50 dose from 3.2 Gy in vehicle-treated cells to 1.9 Gy in 17-AAG-treated cells. This suggests that the absence of Hsp90α delays but does not completely inhibit the repair of most toxic DNA lesions in normal cells.

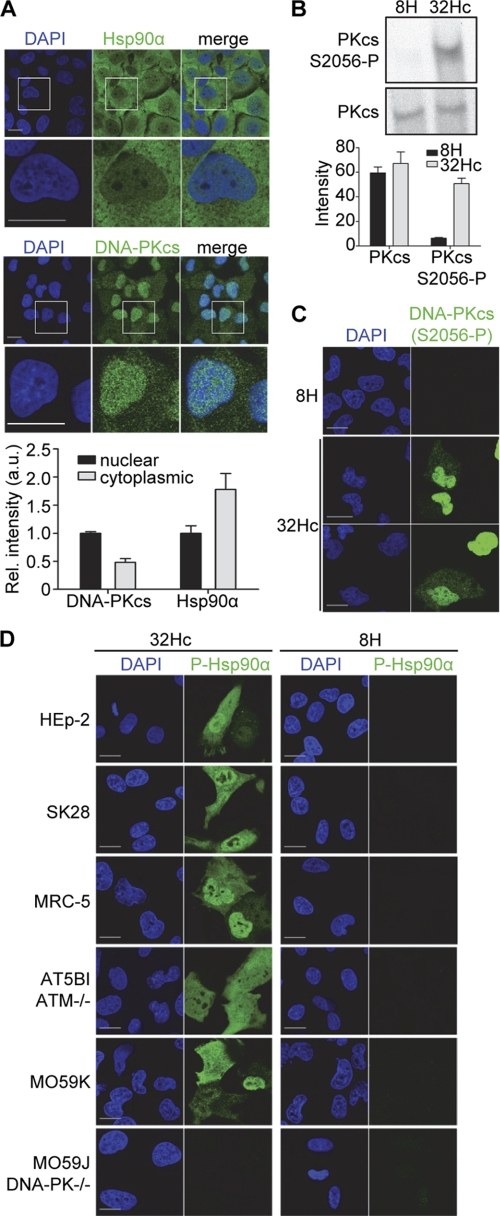

Activation of DNA-PK by Small DNA Molecules Leads to Hsp90α Phosphorylation at Thr-7 in Both the Nucleus and Cytoplasm

The “classical” activities of DNA-PK (DNA repair and V(D)J recombination in immune cells) take place in the nucleus, but DNA-PKcs and Ku proteins have also been detected on membranes (42–44) and in the cytoplasm (45, 46). Hsp90α is present both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A) (47). We therefore hypothesized that Hsp90α might act as a target of DNA-PK in the cytoplasm. DNA-PK activation eventually results in DNA-PK autophosphorylation in trans, leading to dissociation of the catalytic units from the complex (48–51). DNA-PK displayed high levels of autophosphorylation at Ser-2056 in response to the transfection of MRC-5 cells with Dbait 32Hc (Fig. 5B). We used specific antibodies provided Dr. David Chen and co-workers to monitor DNA-PK autophosphorylation at the Ser-2056 site. Phosphorylated DNA-PK was detected after Dbait 32Hc treatment, both in the nucleus and, albeit to a lesser extent, in the cytoplasm of ∼80% of the transfected cells (Fig. 5C). DNA-PK activation by Dbait 32Hc in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus was confirmed by the high levels of nuclear and cytoplasmic Hsp90α phosphorylation at the Thr-7 site in all human DNA-PK-proficient cell lines investigated: HEp-2 (head and neck squamous cell carcinoma), SK-28 (melanoma), MRC-5 (transformed fibroblasts), AT5BI (ATM-deficient transformed fibroblasts), and MO59K (glioblastoma cells) but not in DNA-PK-deficient M059J cells (also from a glioblastoma) (Fig. 5D). This strict DNA-PK dependence suggests that Hsp90α may be a direct target of DNA-PK in the cytoplasm.

FIGURE 5.

Cytoplasmic Hsp90α phosphorylation by DNA-PK in response to Dbait 32Hc. A, immunostaining of total Hsp90α and DNA-PK in untreated MRC-5 cells. Data shown are relative mean pixel intensities with standard deviations from cytoplasmic and nuclear regions of >100 cells. The nuclear signal was set to 1. a.u., arbitrary units. B, MRC-5 cells were transfected with Dbait 32Hc or the short inactive 8H and lysed 1 h after the end of the transfection period. The extracts were immunoblotted and probed for DNA-PKcs (S2056-P). DNA-PK was detected on a separate membrane. The bar chart gives quantifications of the signals with standard deviations from three Western blot analyses. C, immunostaining of DNA-PK (S2056-P) (green) in Dbait 32Hc-treated and 8H-treated MRC-5 cells. Cells were fixed 1 h after transfection. D, indicated cell lines were treated with Dbait 32Hc or 8H and immunostained for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm.

Detection of Irradiation-induced Phosphorylation in Irradiated Bulb Hair

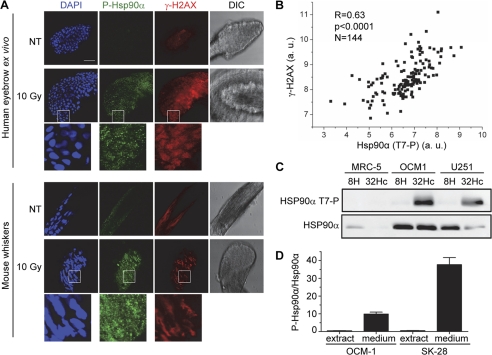

Phosphorylated H2AX has been identified as a potentially useful biomarker of exposure to DNA-damaging agents (52). We thought that Hsp90α, which is highly abundant in all cell types, would be a useful alternative marker. We tested this hypothesis by monitoring the induction of Hsp90α phosphorylation in primary cells, using ex vivo irradiated human hair bulbs. Immunofluorescence staining of ex vivo irradiated human hair bulbs showed a significant increase in both γ-H2AX and Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) levels in response to irradiation (Fig. 6A, upper panel). We then analyzed the bulbs of mouse whiskers, 1 h after irradiation (5 Gy) of the mouse heads. Consistently, the bulbs displayed increased phosphorylation of both markers (Fig. 6A, lower panel). These results confirm that Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7), like γ-H2AX, could be used as a marker of exposure to DNA-damaging treatments.

FIGURE 6.

Phosphorylated Hsp90α in tumor xenografts, tissues, and cell supernatants. A, immunostaining of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) (green) and γ-H2AX (red) in ex vivo irradiated human eye brow bulbs (upper panel) and whisker bulbs from irradiated mice (lower panel), 1 h after irradiation (10 Gy). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast. a.u., arbitrary units. B, Pearson correlation analysis of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) and γ-H2AX levels, as determined from reverse phase protein array analyses of various human tumors (see text) xenografted into mice, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” R and p are Pearson's correlation coefficient and its probability, respectively. C, indicated cells lines were transfected with Dbait 32Hc or 8H and incubated for 24 h without serum. The 50× concentrated cell culture medium was denatured and immunoblotted for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7). Hsp90α was detected on a separate membrane. D, OCM-1 and SK-28 cells were transfected with Dbait 32Hc and incubated without serum for 24 h. Denatured protein from 50× concentrated cell culture medium and from total cell extracts was immunoblotted and probed for Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) and Hsp90α. The signals were quantified and the proportion of total Hsp90α that was phosphorylated was calculated.

Correlation between Basal P-Hsp90α Levels and γ-H2AX Content in Human Tumors and Possible Use of P-Hsp90α as a Biomarker of DNA Damage

Phosphorylated H2AX has been identified as a useful biomarker in clinical oncology (52, 53). First, γ-H2AX quantification can be used to assess the efficacy of DNA damage-inducing chemo- or radiotherapy (25). Second, the spontaneous phosphorylation of H2AX has been reported to be a marker of genetic instability in tumors (54). Hsp90α is produced in larger amounts than H2AX and is also secreted into the extracellular space (55–57). Phosphorylated Hsp90α may therefore constitute a valuable surrogate biomarker. We investigated this issue by determining spontaneous Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) and γ-H2AX levels in human tumor xenografts derived from two melanomas (LU1205 and SK-28), 17 gliomas (FOG, GBM14-RAV, MO59K, SF763, SF767, T98G, TG14-CHA, TG1-HAM, TG17-GIR, U118, U251, U87, U87IC, ODA4GEN (human) and RG2, C6, and F98 (from rat)), one astrocytoma (CB193), one breast carcinoma (BC173BAS), two colon carcinomas (HCT116 and HT29), and one larynx carcinoma (HEp-2). For each tumor type, lysates from 12 samples were analyzed by reverse phase protein array (Fig. 6B). This technology is based on the automated printing of a large number of different cell/tissue lysates onto nitrocellulose bound to histology slides and their analysis with specific antibodies (58). The basal levels of Hsp90α phosphorylation varied considerably between the various tumors analyzed (Fig. 6B). Pearson correlation analysis of the data showed that Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) levels were positively correlated (R = 0.63, p < 0.0001) with γ-H2AX levels (Fig. 6B). As a control, no correlation was found between Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) levels and the levels of phosphoproteins from unrelated pathways, such as EGFR (Thr(P)-669) (data not shown). The analysis of a subset of the tumors (U87, CB193, TG14-CHA, GBM14-RAV, T98G, SF763, TG1-HAM, FOG, SF767, TG17-GIR, LU1205, SK-28, and HEp-2) by Western blotting confirmed the correlation of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) and γ-H2AX levels (R = 0.92, p < 0.0001, supplemental Fig. S5).

A major drawback of many of the proteins identified as potential biomarkers is their limited accessibility. Several groups have reported the secretion of Hsp90α into the extracellular space, and Hsp90α has been detected in the plasma of cancer patients (55–57). We therefore investigated whether the phosphorylated form of Hsp90α could be detected in the cell culture medium supernatant of cell lines. We investigated several cell lines and found that OCM-1 human uveal melanoma and U251 human glioma cells secreted total Hsp90α. Both cell lines also secreted Hsp90α phosphorylated at Thr-7 in response to Dbait 32Hc treatment (Fig. 6C). Phosphorylation of the Thr-7 residue of Hsp90α therefore does not impair its secretion. By contrast, when we compared the proportion of Hsp90α that was phosphorylated in extracts with that in the medium, we found that this proportion was much higher in the medium (Fig. 6D), consistent with the preferential secretion of phosphorylated Hsp90α.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified Hsp90α as an in vivo target of PIKK family members in the response to DNA damage. We mapped the phosphorylation site to the Thr-7 residue and demonstrated the recruitment of phosphorylated Hsp90α to sites of DNA damage. These findings suggest that the function of Hsp90α may be directly modulated in response to DNA damage and are consistent with previous reports of interactions of Hsp90 with BRCA2 and MRN and the radiosensitizing effect of Hsp90 inhibitors (16, 18, 37).

The precise effect of phosphorylation of the Thr-7 residue of Hsp90α remains unclear. Hsp90α consists of three structural regions as follows: a C-terminal region responsible for constitutive dimerization, a middle region involved in binding to client proteins, and an N-terminal region containing the ATP-binding site (59). ATP binding induces closure of the N-terminal “lid” segment and transient dimerization of the N-terminal part of the protein (60). Phosphorylation of the Thr-7 residue at the extreme N terminus of the protein may regulate the open/closed status and ATPase activity of Hsp90α by favoring or hindering N-terminal dimerization. N-terminal phosphorylation may also have consequences for the regulation of substrate choice or the recruitment of specific cofactors. The Hsp90α cofactor Stip1, which is known to modulate Hsp90α ATPase activity (61, 62), was also found to be highly phosphorylated in response to DNA damage in our analysis of the proteins recognized by the a-TQ-P antibody (supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that PIKK activity may modify the interaction of Hsp90α with this cofactor. The site of Hsp90α phosphorylation at the Thr-7 residue is highly conserved in many species, but no such site is present in yeast or bacteria, which have no DNA-PK. Thr-5, which was identified together with Thr-7 as an in vitro phosphorylation site of Hsp90α (34), is much less well conserved, consistent with our identification of Thr-7 as the preferential site for in vivo phosphorylation.

Among the many post-translational modifications implicated in DNA repair, a major role in orchestrating the DNA damage response and organizing DNA repair foci has been attributed to ubiquitination (63). This modification is involved in targeting for proteasome-mediated degradation and serves as a docking site for the accumulation of DNA repair factors. Hsp90α protects some of its clients from degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (64). It is therefore possible that the localization of Hsp90α to sites of DNA damage, as observed in this study, stabilizes specific components of the DNA repair system. This would be consistent with our finding that Hsp90α is required for the maintenance of γ-H2AX foci. Considering the slow kinetics of P-Hsp90α recruitment to sites of DNA damage, an absence or inhibition of Hsp90α may affect late stages in the repair of complex damage or chromatin remodeling. Support for this hypothesis has been provided by studies showing an interaction of Hsp90 with histone H1 (65). A radiosensitizing effect of Hsp90 inhibitors, such as 17-AAG, has been reported by several studies (18). Our results suggest that the Hsp90α isoform, in particular, is important for efficient DNA repair in response to irradiation. This conclusion is supported by our results for the comet assay, which showed similar degrees of repair inhibition for 17-AAG treatment, which inhibits both Hsp90α and Hsp90β, and for Hsp90α silencing (Fig. 4E). The effect on survival was significant but slight, suggesting that most toxic lesions will eventually be repaired by alternative pathways that do not rely on Hsp90α. However, the effect of Hsp90α inactivation on radiosensitivity may be more pronounced in tumor cells, as reported previously for Hsp90 inhibitors (37, 66).

Hsp90α is spontaneously phosphorylated in various human tumors. We found that the basal level of Hsp90α (Thr(P)-7) was correlated with γ-H2AX levels in the various tumors tested, indicating that Thr-7-phosphorylated Hsp90α could be used as a surrogate biomarker for genetic instability in tumor cells. Moreover, Hsp90α can be secreted into the extracellular space (55), and we were able to detect the phosphorylated form in the cell culture media of Hsp90α-secreting tumor cells. It will be interesting to determine whether the phosphorylated form of Hsp90α can also be detected in the serum of cancer patients.

Both Hsp90α and PIKK family members are often overproduced in cancer and may contribute to tumor malignancy and resistance to treatment (14, 67). Our findings establish a direct link between these two proteins, connecting the DNA damage response and the chaperone machinery. A direct role for Hsp90α in DNA damage signaling would account for the radiosensitizing effect of Hsp90 inhibitors. The implication of the isoform Hsp90α, rather than Hsp90β, in the DNA damage response, in particular, suggests that inhibitors specific for Hsp90α may have the same radiosensitizing effect but lower levels of toxicity than general Hsp90 inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David J. Chen for antibodies; Damarys Loew, Wolfgang Faigle, Florent Dingli, and Bérengère Lombard of the Institut Curie mass spectrometry and proteomics platform; Fabrice Cordelières from the imaging platform; Aurélie Barbet, Lamine Coulibaly, and Emilie Henry from the Institut Curie reverse phase protein array platform; and Sylvie Troncale from the Institut Curie “Bioinformatics and Computational Systems Biology of Cancer” unit.

This work was supported by Institut Curie, CNRS, INSERM, and l'Agence National de le Recherche Grant ANR-08-Biot-009-02. M. Quanz is recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship cofinanced by DNA Therapeutics SA. A. Herbette and M. Sayarath are employees of DNA Therapeutics SA. M. Dutreix and J-S. Sun are cofounders of DNA Therapeutics SA, the company holding the patent for Dbait 32Hc.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- DSB

- double strand break

- PIKK

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-like kinase

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

- ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related

- DNA-PK

- DNA-dependent protein kinase

- Gy

- gray

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- IR

- ionizing radiation

- P-Hsp90α

- phosphorylated Hsp90α

- MRN

- Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1

- 17-AAG

- 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wyman C., Kanaar R. (2006) DNA double strand break repair. All's well that ends well. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40, 363–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lieber M. R. (2010) The mechanism of double strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 181–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hartlerode A. J., Scully R. (2009) Mechanisms of double strand break repair in somatic mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 423, 157–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pardo B., Gómez-González B., Aguilera A. (2009) DNA repair in mammalian cells. DNA double strand break repair. How to fix a broken relationship. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 1039–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ciccia A., Elledge S. J. (2010) The DNA damage response. Making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 40, 179–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuoka S., Ballif B. A., Smogorzewska A., McDonald E. R., 3rd, Hurov K. E., Luo J., Bakalarski C. E., Zhao Z., Solimini N., Lerenthal Y., Shiloh Y., Gygi S. P., Elledge S. J. (2007) ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science 316, 1160–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abraham R. T. (2004) PI 3-kinase-related kinases. “Big” players in stress-induced signaling pathways. DNA Repair 3, 883–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meek K., Gupta S., Ramsden D. A., Lees-Miller S. P. (2004) The DNA-dependent protein kinase. The director at the end. Immunol. Rev. 200, 132–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Powley I. R., Kondrashov A., Young L. A., Dobbyn H. C., Hill K., Cannell I. G., Stoneley M., Kong Y. W., Cotes J. A., Smith G. C., Wek R., Hayes C., Gant T. W., Spriggs K. A., Bushell M., Willis A. E. (2009) Translational reprogramming following UVB irradiation is mediated by DNA-PKcs and allows selective recruitment to the polysomes of mRNAs encoding DNA repair enzymes. Genes Dev. 23, 1207–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Basu S., Rosenzweig K. R., Youmell M., Price B. D. (1998) The DNA-dependent protein kinase participates in the activation of NFκB following DNA damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247, 79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Panta G. R., Kaur S., Cavin L. G., Cortés M. L., Mercurio F., Lothstein L., Sweatman T. W., Israel M., Arsura M. (2004) ATM and the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase activate NF-κB through a common MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase/p90(rsk) signaling pathway in response to distinct forms of DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1823–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feng J., Park J., Cron P., Hess D., Hemmings B. A. (2004) Identification of a PKB/Akt hydrophobic motif Ser-473 kinase as DNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41189–41196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Welch W. J., Feramisco J. R. (1982) Purification of the major mammalian heat shock proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 14949–14959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trepel J., Mollapour M., Giaccone G., Neckers L. (2010) Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 537–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banerji U. (2009) Heat shock protein 90 as a drug target. Some like it hot. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dote H., Burgan W. E., Camphausen K., Tofilon P. J. (2006) Inhibition of hsp90 compromises the DNA damage response to radiation. Cancer Res. 66, 9211–9220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsumoto Y., Machida H., Kubota N. (2005) Preferential sensitization of tumor cells to radiation by heat shock protein 90 inhibitor geldanamycin. J. Radiat. Res. 46, 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Camphausen K., Tofilon P. J. (2007) Inhibition of Hsp90. A multitarget approach to radiosensitization. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 4326–4330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quanz M., Chassoux D., Berthault N., Agrario C., Sun J. S., Dutreix M. (2009) Hyperactivation of DNA-PK by double strand break mimicking molecules disorganizes DNA damage response. PLoS One 4, e6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weitzman M. D., Carson C. T., Schwartz R. A., Lilley C. E. (2004) Interactions of viruses with the cellular DNA repair machinery. DNA Repair 3, 1165–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sidera K., Patsavoudi E. (2008) Extracellular HSP90. Conquering the cell surface. Cell Cycle 7, 1564–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barth R. F. (1998) Rat brain tumor models in experimental neuro-oncology. The 9L, C6, T9, F98, RG2 (D74), RT-2, and CNS-1 gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 36, 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stetson D. B., Ko J. S., Heidmann T., Medzhitov R. (2008) Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell 134, 587–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quanz M., Berthault N., Roulin C., Roy M., Herbette A., Agrario C., Alberti C., Josserand V., Coll J. L., Sastre-Garau X., Cosset J. M., Larue L., Sun J. S., Dutreix M. (2009) Small molecule drugs mimicking DNA damage. A new strategy for sensitizing tumors to radiotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 1308–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Redon C. E., Nakamura A. J., Gouliaeva K., Rahman A., Blakely W. F., Bonner W. M. (2010) The use of γ-H2AX as a biodosimeter for total-body radiation exposure in non-human primates. PLoS One 5, e15544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bolte S., Cordelières F. P. (2006) A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 224, 213–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Craig N. L., Roberts J. W. (1981) Function of nucleoside triphosphate and polynucleotide in Escherichia coli recA protein-directed cleavage of phage λ repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 8039–8044 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morita M., Stamp G., Robins P., Dulic A., Rosewell I., Hrivnak G., Daly G., Lindahl T., Barnes D. E. (2004) Gene-targeted mice lacking the Trex1 (DNase III) 3′ → 5′ DNA exonuclease develop inflammatory myocarditis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6719–6727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang Y. G., Lindahl T., Barnes D. E. (2007) Trex1 exonuclease degrades ssDNA to prevent chronic checkpoint activation and autoimmune disease. Cell 131, 873–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu J., He X., Baggerly K. A., Coombes K. R., Hennessy B. T., Mills G. B. (2007) Nonparametric quantification of protein lysate arrays. Bioinformatics 23, 1986–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krull S., Dörries J., Boysen B., Reidenbach S., Magnius L., Norder H., Thyberg J., Cordes V. C. (2010) Protein Tpr is required for establishing nuclear pore-associated zones of heterochromatin exclusion. EMBO J. 29, 1659–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim J. E., Chen J., Lou Z. (2009) p30 DBC is a potential regulator of tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle 8, 2932–2935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nelson J., McFerran N. V., Pivato G., Chambers E., Doherty C., Steele D., Timson D. J. (2008) The 67-kDa laminin receptor. Structure, function, and role in disease. Biosci. Rep. 28, 33–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lees-Miller S. P., Anderson C. W. (1989) The human double-stranded DNA-activated protein kinase phosphorylates the 90-kDa heat-shock protein, hsp90α at two NH2-terminal threonine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 17275–17280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bekker-Jensen S., Lukas C., Kitagawa R., Melander F., Kastan M. B., Bartek J., Lukas J. (2006) Spatial organization of the mammalian genome surveillance machinery in response to DNA strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 173, 195–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goodarzi A. A., Jeggo P., Lobrich M. (2010) The influence of heterochromatin on DNA double strand break repair: Getting the strong, silent type to relax. DNA Repair 9, 1273–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noguchi M., Yu D., Hirayama R., Ninomiya Y., Sekine E., Kubota N., Ando K., Okayasu R. (2006) Inhibition of homologous recombination repair in irradiated tumor cells pretreated with Hsp90 inhibitor 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351, 658–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Takemura H., Rao V. A., Sordet O., Furuta T., Miao Z. H., Meng L., Zhang H., Pommier Y. (2006) Defective Mre11-dependent activation of Chk2 by ataxia telangiectasia mutated in colorectal carcinoma cells in response to replication-dependent DNA double strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30814–30823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Giannini G., Ristori E., Cerignoli F., Rinaldi C., Zani M., Viel A., Ottini L., Crescenzi M., Martinotti S., Bignami M., Frati L., Screpanti I., Gulino A. (2002) Human MRE11 is inactivated in mismatch repair-deficient cancers. EMBO Rep. 3, 248–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stucki M., Clapperton J. A., Mohammad D., Yaffe M. B., Smerdon S. J., Jackson S. P. (2005) MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double strand breaks. Cell 123, 1213–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. FitzGerald J. E., Grenon M., Lowndes N. F. (2009) 53BP1. Function and mechanisms of focal recruitment. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lucero H., Gae D., Taccioli G. E. (2003) Novel localization of the DNA-PK complex in lipid rafts. A putative role in the signal transduction pathway of the ionizing radiation response. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22136–22143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Monferran S., Paupert J., Dauvillier S., Salles B., Muller C. (2004) The membrane form of the DNA repair protein Ku interacts at the cell surface with metalloproteinase 9. EMBO J. 23, 3758–3768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prabhakar B. S., Allaway G. P., Srinivasappa J., Notkins A. L. (1990) Cell surface expression of the 70-kDa component of Ku, a DNA-binding nuclear autoantigen. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 1301–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huston E., Lynch M. J., Mohamed A., Collins D. M., Hill E. V., MacLeod R., Krause E., Baillie G. S., Houslay M. D. (2008) EPAC and PKA allow cAMP dual control over DNA-PK nuclear translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12791–12796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koike M., Koike A. (2005) The Ku70-binding site of Ku80 is required for the stabilization of Ku70 in the cytoplasm, for the nuclear translocation of Ku80, and for Ku80-dependent DNA repair. Exp. Cell Res. 305, 266–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perdew G. H., Hord N., Hollenback C. E., Welsh M. J. (1993) Localization and characterization of the 86- and 84-kDa heat shock proteins in Hepa 1c1c7 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 209, 350–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chan D. W., Lees-Miller S. P. (1996) The DNA-dependent protein kinase is inactivated by autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 8936–8941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Douglas P., Moorhead G. B., Ye R., Lees-Miller S. P. (2001) Protein phosphatases regulate DNA-dependent protein kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18992–18998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ding Q., Reddy Y. V., Wang W., Woods T., Douglas P., Ramsden D. A., Lees-Miller S. P., Meek K. (2003) Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase is required for efficient end processing during DNA double strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5836–5848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weterings E., Chen D. J. (2007) DNA-dependent protein kinase in nonhomologous end joining. A lock with multiple keys? J. Cell Biol. 179, 183–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Redon C. E., Nakamura A. J., Zhang Y. W., Ji J. J., Bonner W. M., Kinders R. J., Parchment R. E., Doroshow J. H., Pommier Y. (2010) Histone γH2AX and poly(ADP-ribose) as clinical pharmacodynamic biomarkers. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 4532–4542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu S. K., Olive P. L., Bristow R. G. (2008) Biomarkers for DNA DSB inhibitors and radiotherapy clinical trials. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27, 445–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee-Kirsch M. A., Gong M., Chowdhury D., Senenko L., Engel K., Lee Y. A., de Silva U., Bailey S. L., Witte T., Vyse T. J., Kere J., Pfeiffer C., Harvey S., Wong A., Koskenmies S., Hummel O., Rohde K., Schmidt R. E., Dominiczak A. F., Gahr M., Hollis T., Perrino F. W., Lieberman J., Hübner N. (2007) Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 39, 1065–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang X., Song X., Zhuo W., Fu Y., Shi H., Liang Y., Tong M., Chang G., Luo Y. (2009) The regulatory mechanism of Hsp90α secretion and its function in tumor malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21288–21293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li W., Li Y., Guan S., Fan J., Cheng C. F., Bright A. M., Chinn C., Chen M., Woodley D. T. (2007) Extracellular heat shock protein-90α. Linking hypoxia to skin cell motility and wound healing. EMBO J. 26, 1221–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen J. S., Hsu Y. M., Chen C. C., Chen L. L., Lee C. C., Huang T. S. (2010) Secreted heat shock protein 90α induces colorectal cancer cell invasion through CD91/LRP-1 and NF-κB-mediated integrin αV expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25458–25466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gulmann C., Sheehan K. M., Kay E. W., Liotta L. A., Petricoin E. F., 3rd (2006) Array-based proteomics. Mapping of protein circuitries for diagnostics, prognostics, and therapy guidance in cancer. J Pathol 208, 595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pearl L. H., Prodromou C., Workman P. (2008) The Hsp90 molecular chaperone. An open and shut case for treatment. Biochem. J. 410, 439–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Prodromou C., Panaretou B., Chohan S., Siligardi G., O'Brien R., Ladbury J. E., Roe S. M., Piper P. W., Pearl L. H. (2000) The ATPase cycle of Hsp90 drives a molecular “clamp” via transient dimerization of the N-terminal domains. EMBO J. 19, 4383–4392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Häcker H., Mischak H., Miethke T., Liptay S., Schmid R., Sparwasser T., Heeg K., Lipford G. B., Wagner H. (1998) CpG-DNA-specific activation of antigen-presenting cells requires stress kinase activity and is preceded by nonspecific endocytosis and endosomal maturation. EMBO J. 17, 6230–6240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Song Y., Masison D. C. (2005) Independent regulation of Hsp70 and Hsp90 chaperones by Hsp70/Hsp90-organizing protein Sti1 (Hop1). J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34178–34185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Polo S. E., Jackson S. P. (2011) Dynamics of DNA damage-response proteins at DNA breaks. A focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 25, 409–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Whitesell L., Lindquist S. L. (2005) HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Alekseev O. M., Widgren E. E., Richardson R. T., O'Rand M. G. (2005) Association of NASP with HSP90 in mouse spermatogenic cells. Stimulation of ATPase activity and transport of linker histones into nuclei. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2904–2911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bisht K. S., Bradbury C. M., Mattson D., Kaushal A., Sowers A., Markovina S., Ortiz K. L., Sieck L. K., Isaacs J. S., Brechbiel M. W., Mitchell J. B., Neckers L. M., Gius D. (2003) Geldanamycin and 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin potentiate the in vitro and in vivo radiation response of cervical tumor cells via the heat shock protein 90-mediated intracellular signaling and cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 63, 8984–8995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bolderson E., Richard D. J., Zhou B. B., Khanna K. K. (2009) Recent advances in cancer therapy targeting proteins involved in DNA double strand break repair. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 6314–6320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Moore R., Champeval D., Denat L., Tan S. S., Faure F., Julien-Grille S., Larue L. (2004) Involvement of cadherins 7 and 20 in mouse embryogenesis and melanocyte transformation. Oncogene 23, 6726–6735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.