Background: Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (L-PGDS) is one of the most abundant proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid with unknown function.

Results: L-PGDS regulates glial cell migration and morphology through myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS)-dependent and prostaglandin D2-independent pathways.

Conclusion: L-PGDS may be involved in reactive gliosis and contribute to neuroinflammatory diseases.

Significance: L-PGDS could be a therapeutic target based on the pathological implications in neuroinflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Brain, Glia, Migration, Neuroinflammation, Prostaglandins

Abstract

Prostaglandin D synthase (PGDS) is responsible for the conversion of PGH2 to PGD2. Two distinct types of PGDS have been identified: hematopoietic-type PGDS (H-PGDS) and lipocalin-type PGDS (L-PGDS). L-PGDS acts as both a PGD2-synthesizing enzyme and as an extracellular transporter of various lipophilic small molecules. Although L-PGDS is one of the most abundant proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid, little is known about the function of L-PGDS in the central nervous system (CNS). To better understand the role of L-PGDS in the CNS, effects of L-PGDS on the migration and morphology of glial cells were investigated. The L-PGDS protein accelerated the migration of cultured glial cells. Expression of the L-pgds gene was detected in glial cells and neurons. L-PGDS protein also induced morphological changes in glia similar to the characteristic phenotypic changes in reactive gliosis. L-PGDS-induced cell migration was associated with augmented formation of actin filaments and focal adhesion, which was accompanied by activation of AKT, RhoA, and JNK pathways. L-PGDS protein injected into the mouse brain promoted migration and accumulation of astrocytes in vivo. Furthermore, the cell migration-promoting effect of L-PGDS on glial cells was independent of the PGD2 products. The L-PGDS protein interacted with myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS) to promote cell migration. These results demonstrate the critical role of L-PGDS as a secreted lipocalin in the regulation of glial cell migration and morphology. The results also indicate that L-PGDS may participate in reactive gliosis in an autocrine or paracrine manner, and may have pathological implications in neuroinflammatory diseases.

Introduction

Prostaglandin D synthase (PGDS)3 catalyzes the isomerization of PGH2 to produce PGD2 (1, 2). Two distinct types of PGDS have been purified and characterized; one is the lipocalin-type PGDS (L-PGDS) that was previously known as the brain-type enzyme or glutathione (GSH)-independent enzyme (3, 4), and the other is hematopoietic PGDS, the spleen-type enzyme or GSH-requiring enzyme (5, 6). L-PGDS is a member of the lipocalin family, which binds and transports small lipophilic molecules such as retinal, retinoic acid (7), biliverdin, bilirubin (8), gangliosides (9), as well as amyloid β peptides (10, 11). L-PGDS, also known as β-trace, is one of the most abundant proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid (12, 13). L-PGDS is expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), retina, melanocytes, heart, and reproductive organs (3). L-PGDS plays an important role in diverse cellular processes, such as cellular apoptosis/survival (14–16), cell differentiation (17), cell cycle progression (18), inflammation (19, 20), and metabolic syndrome (18, 21). Previously, L-PGDS has also been proposed as the endogenous amyloid β-chaperone that prevents amyloid deposition in vivo (10). Recently, L-PGDS-deficient mice exhibited an exacerbated phenotype following transient or permanent ischemic brain injury, indicating a critical role of L-PGDS in protection against cerebral ischemia (22). L-PGDS has also been shown to play important roles in spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer disease (10, 23–26). Despite numerous publications on L-PGDS in various peripheral tissues, little is known about the role of L-PGDS in the CNS. Moreover, it has not been investigated whether and how L-PGDS regulates cell migration and morphology of brain glial cells.

The CNS consists of neurons and glial cells. Glial cells provide structural and functional support and protection for neurons. Microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes are the major types of CNS supporting glial cells. As a result of brain injury, glial cells undergo rapid changes in their morphological phenotype and migratory properties; the combination of which is known as reactive gliosis. Reactive gliosis specifically refers to the accumulation of enlarged glial cells, notably microglia and astrocytes, appearing immediately after CNS injury has occurred. The release of inflammatory molecules by injured tissues and glial cells themselves stimulates motility, directed migration, or a combination of both to recruit glial cells toward the injury sites (27). Hence, integrative understanding of glial cell migration and morphology will provide insights into the molecular mechanisms of various brain injuries and pathologies.

In the present study, we attempted to determine the role of L-PGDS in migration and morphological changes of glial cells such as microglia and astrocytes. Our results indicate that L-PGDS expressed in glia and neurons may induce glial cell migration and morphological changes in a paracrine or autocrine manner. Additionally, the L-PGDS protein injected into the mouse brain promoted astrocyte migration toward injury sites in vivo. Last, the AKT-RhoA-JNK pathways appear to participate in the actions of L-PGDS, which may be mediated through myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS), a newly identified binding partner of L-PGDS.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Cells

Prostaglandin D2 and polymyxin B were obtained from Sigma. Specific small-molecule inhibitors, such as AKT inhibitor (1L6-hydroxymethyl-chiroinositol-2-(R)-2-O-methyl-3-O-octadecyl-sn-glycerocarbon), JNK inhibitor (SP600125), MEK1 inhibitor (PD98059), and p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB 203580) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). A specific Rho inhibitor (C3 transferase) was obtained from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO). DP1 receptor antagonist (BW A868C) and DP2 receptor antagonist (BAY-u3405) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). All other chemicals, unless otherwise stated, were obtained from Sigma. NIH3T3 mouse fibroblast cells and the transformed mouse cerebral endothelial cell line bEnd.3 (CRL-2299; ATCC, Manassas, VA) (28) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen). The mouse primary astrocyte, microglia, or mixed glial cultures were prepared from the brains of 0–3-day-old ICR mice (Samtako Co., Osan, Korea), as previously described (29). Primary astrocyte and microglia cultures were prepared from mixed glial cultures by differential shaking (30) and mild trypsinization methods (31), respectively. Primary cultures of dissociated cerebral cortical neurons were prepared from embryonic day 20 (E20) ICR mice, as described previously (32, 33). Briefly, mouse embryos were decapitated, and the brains were rapidly removed and placed in a culture dish with cold PBS. The cortices were isolated, and then transferred to a culture dish containing 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) in PBS for 30 min at 37 °C. After two washes in serum-free neurobasal media (Invitrogen), the cortical tissues were mechanically dissociated with gentle pipetting. Dissociated cortical cells were seeded onto six-well plates coated with poly-d-lysine (BD Biosciences), using neurobasal medium containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen), 0.5 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml of penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen), N2 supplement (Invitrogen), and a B27 supplement (Invitrogen). Cultures were maintained by changing the media every 2–3 days, and were grown at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. The purity of the glia and neuronal cultures was determined by immunocytochemical staining, using antibodies against Iba-1, GFAP, or microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2; Promega). Animals used in the current research were acquired and cared for in accordance with guidelines published in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kyungpook National University School of Medicine.

Purification of Recombinant Lipocalin-type Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Protein

The mouse L-pgds cDNA was subcloned into the prokaryotic expression vector pET28a for bacterial expression. Mouse recombinant L-PGDS protein was expressed as a His6 fusion protein in the BL21(DE3) pLysS strain of Escherichia coli. The expression of recombinant proteins was induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 3 h, and then cells were lysed by sonication. The protein was purified by using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), followed by elution with imidazole. The purified protein was dialyzed using Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis cassettes (Pierce), and then concentrated using centrifugal dialysis filtration tubes (Millipore).

Cell Migration Assays

Cell migration was determined by either Boyden chamber assay (Transwell migration assay) or wound healing assays. Transwell migration assay using a 48-well Boyden chamber (NeuroProbe, Gaithersburg, MD) was done according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were either transfected with L-pgds cDNA or treated with L-PGDS protein (0–100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were then harvested by trypsinization, resuspended in DMEM, and added to the upper chamber at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. Growth media were placed into base wells separated from the top wells by polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate filters (8-μm pore size; 25 × 80 mm; NeuroProbe). Cells were incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for 12–72 h to evaluate cell migration. Zigmond-Hirsch checkerboard analysis (34) was performed in triplicate to distinguish between concentration-dependent cell migration (chemotaxis) and random migration (chemokinesis). L-PGDS protein of varying concentrations was added to the upper and/or lower wells of the Boyden chambers with cells added to the upper chamber at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well, and incubated for the indicated time period. At the end of the incubation, non-migrating cells on the upper side of the membrane were removed with a cotton swab. Migrated cells on the lower side of the membrane were fixed with methanol for 10 min and stained with Mayer's hematoxylin (Dakocytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for 20 min. Photomicrographs of five random fields were taken (Olympus CK2; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (original magnification ×100), and cells were enumerated to calculate the average number of cells that had migrated. All migrated cells were counted, and the results presented as the mean ± S.D. of triplicates. For the in vitro wound healing assay, a scratch wound was created using a 200-μl pipette tip on confluent cell monolayers in 24-well culture plates, and DMEM containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml of penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen) was added with or without pharmacological inhibitors, L-PGDS protein, and PGD2 for 48 h. Cells were incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 during migration of monolayer into the cleared wound area. The wound area was observed by microscopy (Olympus CK2) (magnification, ×100). Relative cell migration distance was determined by measuring the wound width and subtracting this from the initial value as previously described: cell migration distance = initial wound width at day 0 − wound width at the day of measurement (35). Three nonoverlapping fields were selected and examined in each well (three wells per experimental group). The results are presented as a fold-increase of the migration distance compared with control.

Morphological Analysis of Cells

The morphological analysis of microglia was done with phase-contrast microscopy following peroxidase-labeled isolectin B4 staining (1:500 dilution; Sigma) (36). Deramification of microglia was quantified as previously described with a slight modification (37, 38). The percentage of ramified cells was determined from a minimum of five randomly chosen fields containing at least 100 cells. The morphological analysis of astrocytes was done with fluorescence microscopy (Olympus BX50). Cells were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS/Tween 20 for 10 min and incubated in PBS containing 3% BSA and mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (1:30 dilution; Biogenex, San Ramon, CA). After two washes in PBS/Tween 20, cells were incubated with anti-mouse IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (BD Biosciences). Astrocyte processes were quantified as previously described (29, 38). The number of astrocytes processed was determined from a minimum of five randomly chosen microscopic fields containing at least 100 cells. Vinculin or phalloidin staining of NIH3T3 cells or glial cells was done as previously described (39). Briefly, cells were cultured on sterile coverslips in 24-well plates, and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and rinsed twice with PBS. Cells were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS/Tween 20 for 10 min and incubated in PBS containing 3% BSA and a mouse anti-vinculin antibody (1:30 dilution) or 0.12 μg/ml of TRITC-conjugated phalloidin (Actin Cytoskeleton and Focal Adhesion staining kit; Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents). After two washes in PBS/Tween 20, cells were incubated with 0.1 μg/ml of DAPI (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), followed by incubation with anti-mouse IgG-FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (BD Biosciences). The samples were mounted and observed with confocal microscopy (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Microscopic images were processed with the MetaMorph Imaging System (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Transient Transfection with cDNA or siRNA

The full-length cDNA of mouse L-pgds was fused with myc and His6 tag at the N-terminal, and subcloned into expression vector pcDNA3.1. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells in 6-well plates were transiently transfected with 4 μg of myc-tagged L-pgds cDNA using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. An empty pcDNA3.1 vector was used as a control for the transient expression of myc-L-pgds. Two days after the transfection, cells were used for the experiments. The expression of the myc-L-PGDS protein in the transient transfectants was confirmed by Western blot using a myc tag antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). For the knockdown of Marcks expression, mouse Marcks siRNA pool (CCUUCAAGAAGUCCUUCAAtt, UUGAAGGACUUCUUGAAGGtt; GGCUUCUCCUUCAAGAAGAtt, UCUUCUUGAAGGAGAAGCCtt; GGAAGUAACGUUGCUUACAtt, UGUAAGCAACGUUACUUCCtt; catalog number sc-35858) and control siRNA (sc-37007) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The siRNA transfection of NIH3T3 fibroblast cells or glial cells was done using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 48 h after the transfection, cells were used for the experiments.

L-PGDS ELISA

An indirect ELISA was used for the recombinant mouse L-PGDS protein measurements. Conditioned media were collected from the mixed glial cultures, and centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris. Microtiter plate wells were coated with conditioned medium overnight (diluted 1:1 in 50 mm carbonate buffer, pH 9.6) (100 μl/well in triplicate wells). Plates were washed with PBS-T and blocked with PBS, 5% BSA for 1 h. Plates were emptied and tapped out onto dry paper towels. Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse L-PGDS antibody was added (Cayman Chemical; 1 μg/ml) and incubated for 5 h. Plates were washed 3 times with PBS-T to remove unbound antibody. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Pierce; 1:1000 dilution) was added and incubated for 1 h. Plates were washed 3 times with PBS-T and developed by the addition of 100 μl of chromogenic substrate (R&D Systems). The purified recombinant mouse L-PGDS protein was used as a standard.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in triple detergent lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Protein concentration in cell lysates was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). An equal amount of protein from each sample was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and sequentially incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-AKT at Ser473 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit polyclonal anti-total AKT antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-JNK at Thr183/Tyr185 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit polyclonal anti-total JNK antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), and monoclonal anti-α-tubulin clone B-5-1-2 mouse ascites fluid (Sigma)), and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG; Amersham Biosciences), followed by ECL detection (Amersham Biosciences).

Rho GTPase Activity Assay

Cells were treated with stimuli in a 100-mm culture dish, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in a lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Molecular Biochemicals)). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, protein concentrations were determined, and the GTP-bound Rho in the lysates was measured by the effector pulldown assay using the EZ-Detect Rho activation kit (Pierce). Briefly, cell lysates were incubated with agarose-immobilized glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Rhotekin, and the co-precipitates were subjected to anti-Rho Western blot analysis to assess the amount of GTP-bound Rho proteins. The anti-Rho antibody used in this study is known to recognize RhoA, RhoB, and RhoC.

Assessment of Prostaglandin D2 Formation

Enzyme immunoassays were done to assess PGD2 formation. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were either transfected with L-pgds cDNA (4 μg) or treated with l-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. The PGD2-MOX kit (Cayman Chemical) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. This kit is based on the conversion of PGD2 to a stable methoxime derivative by treatment with methoxamine hydrochloride. Medium from the cell culture was sampled and analyzed.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Point mutations of L-PGDS at the enzymatic active site were created using the QuikChange® Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene Cloning Systems) as per the manufacturer's instructions. A point mutation (C65A) was created by exchanging Cys65 with an alanine residue. The mutation was confirmed by sequence analysis, and the mutant L-PGDS proteins were expressed and purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen) in a manner similar to wild-type protein. The C65A mutant without the enzymatic activity has been previously reported (40).

Immunoprecipitation

NIH3T3 fibroblast or glial cells were treated with the recombinant L-PGDS protein (1 μg/ml), and then cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 1 h and rinsed twice with PBS. Cells were lysed in triple-detergent lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The lysates were centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentration in the cell lysates was determined using the Quant-iT Protein Assay kit (Molecular Probes). To remove nonspecific binding proteins in the lysates, the samples were incubated in a ∼30-μl packed volume of recombinant protein G-agarose for 1 h at 4 °C. After a brief centrifugation, supernatants were collected and then incubated with anti-L-PGDS antibody (Cayman Chemical; 1 μg/ml) for 4 h at 4 °C. Protein G-agarose (30 μl) was then added and incubated for 4 h. Afterward, L-PGDS·Ab·protein G-agarose complexes were washed three times with wash buffer (50 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol), and a sample buffer (20% glycerol, 6% SDS, and 10% 2-mercaptoethanol) was added. The samples were boiled for 5 min and centrifuged. Supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10% gel) followed by Western blot analysis.

Identification of Coimmunoprecipitated Proteins

Coimmunoprecipitated proteins were identified as described previously (41). Briefly, immunoprecipitation samples were separated by electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining. The protein band of interest was excised from the silver-stained gel for in-gel tryptic digestion. The excised gel slices were destained and shrunk by dehydration in acetonitrile and dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Proteins within the shrunken gel slices were then digested overnight with trypsin at a substrate/enzyme ratio of 10:1 (w/w) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0). The enzyme reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.1% formic acid in water. Peptides from gel pieces were extracted by sonication for 10 min, and the supernatants containing the peptides were transferred to new tubes. Peptides were analyzed using a liquid chromatography (LC) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) system with reverse-phase LC, which consisted of a Surveyor MS pump (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA), a Spark autosampler (Spark Holland, Emmen, The Netherlands), and a Finnigan LTQ linear ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron) equipped with nanospray ionization sources. All MS/MS data were searched against the IPI mouse protein data base (version 3.16) using the SEQUEST algorithm (Thermo Electron) incorporated into BioWorks software (version 3.2).

Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells in 6-well plates by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription was done using SuperScript II (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT) primer. Traditional PCR amplification using primer sets specific for lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (L-pgds) was done as follows: 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min for 23 cycles followed by an extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. The nucleotide sequences of the primers were based on published cDNA sequences of the mouse L-pgds, Marcks, or β-actin: L-pgds forward, TCC GGG AGA AGA AAG CTG TA; L-pgds reverse, CAT AGT TGG CCT CCA CCA CT; Marcks forward, GTC GCC TTC CAA AGC AAA T; Marcks reverse, GCA GCC TCA TCC TTT TCG; β-actin forward, ATC CTG AAA GAC CTC TAT GC; β-actin reverse, AAC GCA GCT CAG TAA CAG TC. The PCR was done with a DNA Engine Tetrad Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). For the analysis of the PCR products, 10 μl of each PCR was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel and detected under UV light following ethidium bromide staining. β-Actin was used as an internal control.

Assessment of Cytotoxicity by 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide Assay

NIH3T3 cells or glial cultures (5 × 104 cells in 200 μl/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with various stimuli for the specific time periods. After treatment, the medium was removed and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (0.5 mg/ml) was added, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h in a CO2 incubator. After insoluble crystals were completely dissolved in DMSO, absorbance at 570 nm was measured by using a microplate reader (Anthos Labtec Instruments, Wals, Austria).

Intrastriatal Injection of L-PGDS Protein

Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (n = 3) weighing about 30 g (Koatech, Pyeongtaek, Korea) were used for the experiments. Mice were housed and maintained at 22 °C on a 12-h day/night cycle. Free access to food and water was allowed. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Zoletil (Tiletamine/Zolazepam; 30 mg/kg) and Ropum (10 mg/kg), and positioned in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). The mice were placed on a homeothermic heat blanket (Harvard Apparatus Co., South Natick, MA) at 37 °C to maintain normal body temperature during surgery. The skull was exposed by a skin incision, and a small hole was drilled through the skull. To avoid passing through the ventricles, the guide cannula was implanted at the stereotaxic coordinates of 1-mm anterior to the bregma, 2-mm lateral to the bregma, and 4-mm below the skull using a 22-gauge needle and cemented. Intrastriatal injection of the vehicle or recombinant L-PGDS protein (1 μl; 1 mg/ml) was done using a 26-gauge needle. The flow rate of the injection was 0.1 μl/min maintained by a microsyringe pump (Harvard Apparatus Co.). After removing the needle, the skin was sutured with 6.0-mm silk thread. Forty-eight hours after the injection, the mice were sacrificed. For immunohistochemical analysis, animals were anesthetized by ether and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were post-fixed and cryoprotected with 30% sucrose solution for 1 day. The fixed brains were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek) for frozen sections and then cut into 12-μm thick coronal sections. The tissues were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with 1% BSA and 5% normal donkey serum. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated at 4 °C overnight with the mouse monoclonal antibody against GFAP (1:500 dilution; BD Biosciences). The sections were then incubated with donkey Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). The sections were mounted on DAPI-containing gelatin solution. Data acquisition and immunohistological intensity measurement of GFAP staining was performed with a NIH Image J program. Composite images of the stained sections were FFT band-pass filtered to eliminate low-frequency drifts (>20 pixels = 50 μm) and high-frequency noises (<1 pixel = 2.5 μm). The images were binary thresholded at 50% of the background level, and the particles were then converted to a subthreshold image area with a size less than 300 and larger than 5 pixels, which was judged as GFAP-positive cells. The range (5–300 pixels) was obtained from the analyzed size of GFAP-positive cells from six sections of each animal. To count the GFAP positive cells, five squares (500 × 500 μm) were placed in the region of the injection in the subthreshold image of the six independent sections. The cells in the five squares were counted and statistically analyzed.

Intracortical Injection of L-PGDS Protein

The intracerebral injection of the vehicle or recombinant L-PGDS protein (1 μl; 1 mg/ml) was done at the stereotaxic coordinates of 1-mm anterior to the bregma, 3-mm lateral to the bregma, and 3-mm below the skull using a 26-gauge needle. The flow rate of the injection was 0.1 μl/min maintained by a microsyringe pump (Harvard Apparatus Co.). Horizontal brain sections were immunohistochemically stained with GFAP antibody at 48 h after intracerebral injection. For quantification, the images were converted into binary images by the NIH Image J program. Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (n = 3) weighing about 30 g (Koatech) were also used.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± S.D. from three or more independent experiments, unless stated otherwise. Statistical comparisons between different treatments were done by either a Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests using the SPSS program (version 18.0K) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences with a p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

L-PGDS-induced Glial Cell Migration and Morphological Changes

To determine the effects of L-PGDS on glial cell migration, glial cultures were treated with different concentrations of recombinant L-PGDS protein (10–100 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods, and cell migration was then assessed using the Boyden chamber assay. For this purpose, the recombinant L-PGDS protein was expressed in bacteria and purified (Fig. 1A). The cell migration-promoting activity of L-PGDS was found in primary microglia and astrocyte cultures, where the migration of L-PGDS-treated glial cells across the membrane was greater than that of the untreated cells after 12–72 h (Fig. 1, B and C). Checkerboard analysis indicated that the L-PGDS-induced glial migration was chemotaxis (directed movement), rather than chemokinesis (random movement) (supplemental Fig. S1). Glial cell migration toward the lower chamber was proportional to the concentrations of L-PGDS protein placed in the lower chamber, but not upper chamber, thereby indicating that the L-PGDS protein was chemotactic to glial cells. These results led us to hypothesize that L-PGDS may mediate phenotypic changes of the glia that occur during reactive gliosis in the CNS. Reactive gliosis involves glial migration as well as morphological changes (42–45). To determine whether L-PGDS is responsible for the morphological features of reactive gliosis phenotype, we next evaluated the effect of recombinant L-PGDS protein on glial cell morphology. Treatment with the recombinant L-PGDS protein induced distinct morphological changes in the microglia and astrocytes: amoeboid transformation of the microglia was induced by L-PGDS protein treatment (Fig. 2A), whereas cellular process extension was observed for astrocytes (Fig. 2B). These morphological changes and enhanced motility reflect the phenotypic alterations that occur during reactive gliosis. A similar pattern of structural changes in glia was observed after treatment with PGD2 (Fig. 2), which has been previously shown to influence glial activation (46) and inflammatory cell migration (47, 48). PGD2, as a product of PGDS enzyme, was used for comparison purposes. The expression of L-pgds mRNA was detected in primary microglia, astrocytes, or cortical neuron cultures, but not in microvascular endothelial cells (supplemental Fig. S2), indicating the widespread expression of L-pgds in the CNS. The recombinant L-PGDS protein showed a modest toxicity toward the primary microglia cultures after long-term exposure, and the toxicity was insignificant in the astrocyte cultures (supplemental Fig. S3). Polymyxin B did not affect the L-PGDS protein activity in microglia and astrocytes, arguing against LPS contamination in the L-PGDS protein (supplemental Fig. S4, A and B). For the direct quantification of L-PGDS protein levels in the conditioned media of glial cultures, L-PGDS-specific ELISA was performed. The L-PGDS concentration in the conditioned media of mixed glial cultures was ∼36 ng/ml. L-PGDS concentration used in the current study is based on this and previous studies (2), which has shown that L-PGDS protein concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood were ∼25 and ∼0.4 μg/ml, respectively.

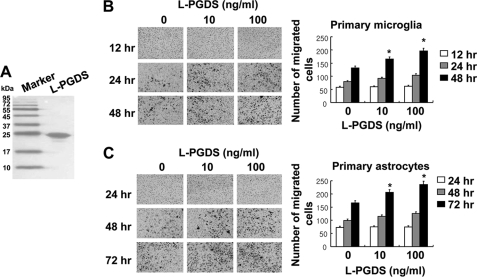

FIGURE 1.

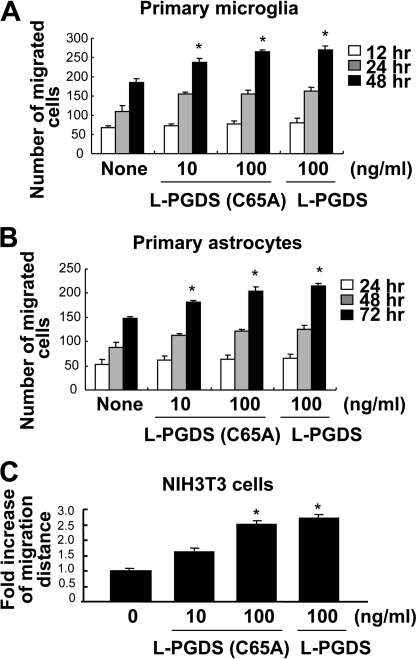

Recombinant L-PGDS protein promotes the migration of microglia and astrocytes. Histidine-fused L-PGDS protein was expressed in bacteria, and separated by SDS-PAGE (A). Primary microglia cultures (1 × 104 cells/upper well) (B) or primary astrocyte cultures (1 × 104 cells/upper well) (C) were treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (10–100 ng/ml) and placed in the Boyden chambers for incubation at 37 °C for 12–48 and 24–72 h, respectively, to evaluate cell migration. A representative microscopic image for each condition is shown (magnification ×100). The quantification of cell migration was done by enumerating the migrated cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 compared with the untreated control at the same time point.

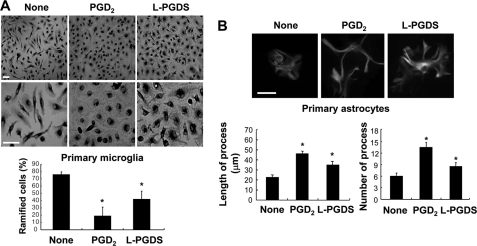

FIGURE 2.

The effect of recombinant L-PGDS protein on the morphology of microglia and astrocytes. The addition of recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) or PGD2 (100 ng/ml) induced morphological changes in primary microglia cultures (A) and primary astrocytes (B) after 24 h. Primary microglia were stained with the peroxidase-labeled isolectin B4, followed by incubation with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (magnification ×100 or 200). Primary astrocytes were stained with GFAP antibody (magnification ×400), followed by incubation with anti-mouse IgG-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody. Scale bar, 25 μm. The percentage of ramified microglia, the length of the longest process, or the number of process in each astrocyte was assessed by examining several randomly chosen microscopic fields. The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; compared with the untreated control (None).

L-pgds cDNA Transfection and Protein Treatment-induced NIH3T3 Cell Migration

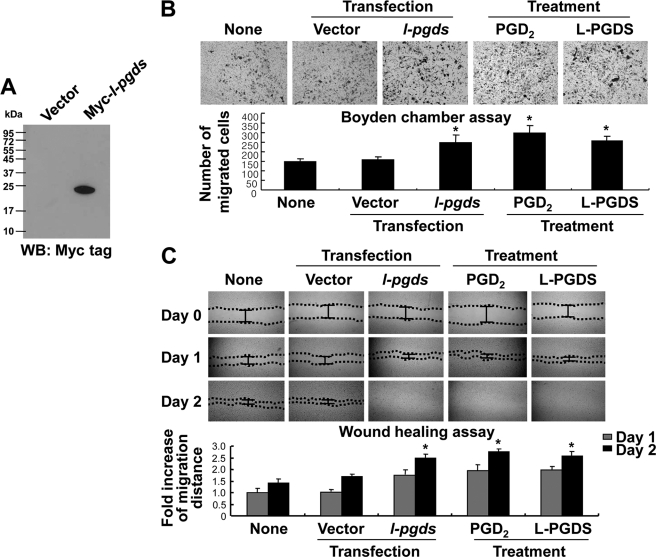

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms of L-pgds-induced cellular migration, NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were utilized as a model. The myc-tagged L-pgds cDNA was introduced into NIH3T3 fibroblast cells to generate a cell line that overexpressed L-pgds (Fig. 3A). Cell migration assays such as the Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 3B) and wound healing assay (Fig. 3C) revealed that both L-pgds cDNA transfection and L-PGDS protein treatment induced cell migration (Fig. 3, B and C). In the wound healing assay, NIH3T3 fibroblast cells that were either transfected with L-pgds cDNA or treated with L-PGDS protein or PGD2 became confluent at 48 h (Fig. 3C). Polymyxin B did not affect L-PGDS protein activity in NIH3T3 cells, arguing against LPS contamination in the L-PGDS protein (supplemental Fig. S4C).

FIGURE 3.

L-PGDS promotes the migration of NIH3T3 fibroblast cells. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were transiently transfected with either pcDNA3.1 empty vector or myc-tagged L-pgds, and the expression of L-pgds in the transfectants was confirmed by Western blot analysis using anti-MYC tag antibody (WB: MYC tag) (A). NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were either transfected with L-pgds or treated with PGD2 (100 ng/ml) or L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml), and then either the Boyden chamber assay (IB) or wound healing assay (C) was done to evaluate cell migration. A representative microscopic image for each condition is shown (magnification ×100) (upper). The quantification of cell migration was done by either measuring the degree of wound closure (the wound healing assay) or enumerating the migrated cells (the Boyden chamber assay) as described under “Experimental Procedures” (lower). The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 compared with the untreated control (None) at the same time point.

L-PGDS Modulated Distribution of Focal Adhesion and Organization of Actin Stress Fibers, Role of RhoA, AKT, and JNK Pathways in the L-PGDS-induced Cell Migration

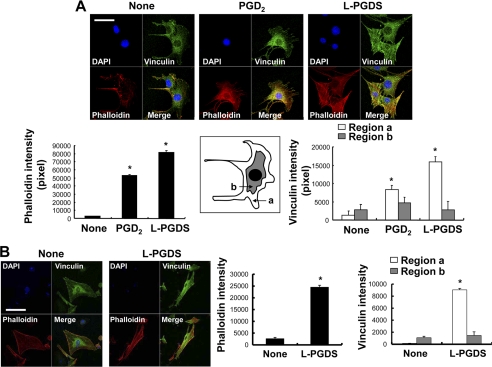

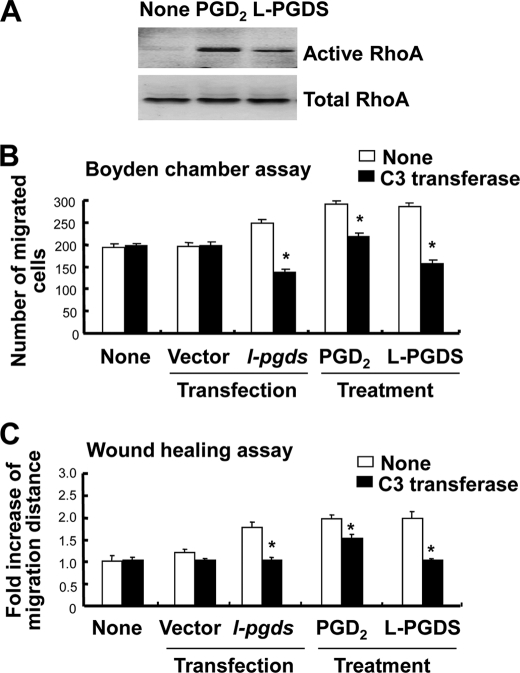

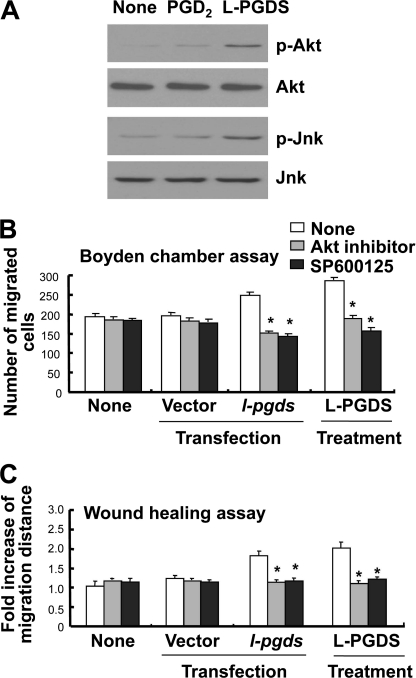

Because the cytoskeleton has been previously implicated in the regulation of cell migration and morphology (49–54), a possible involvement of focal adhesion and actin stress fibers in the L-PGDS-induced cell migration and morphological change was investigated in NIH3T3 cells. Formation of actin filaments increased in the recombinant L-PGDS protein-treated cells compared with untreated control cells as determined by phalloidin staining (Fig. 4A). In addition, recombinant L-PGDS protein augmented vinculin staining in the peripheral region of the cell, suggesting an increase in vinculin distribution at the focal adhesion (Fig. 4A). PGD2 showed similar effects on focal adhesion and actin cytoskeleton organization, but to a lesser degree (Fig. 4A). L-PGDS-induced morphological change was also observed in glial cells: L-PGDS increased phalloidin and vinculin staining in glial cells in a manner similar to those in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 4B). RhoA (55–57), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT (58, 59), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (60, 61) signaling pathways play a critical role in cell migration, the possible involvement of these pathways in the L-PGDS-induced cell migration was next determined in NIH3T3 cells. The recombinant L-PGDS protein and PGD2 increased the amount of active RhoA (Fig. 5A). Pharmacological inhibition of RhoA using C3 transferase significantly attenuated L-PGDS-induced cell migration as determined by the Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 5B) and wound healing assay (Fig. 5C). The C3 transferase similarly reduced L-pgds transfection- or PGD2-induced cell migration. The levels of phospho-AKT and phospho-JNK increased in NIH3T3 fibroblast cells treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (Fig. 6A). The AKT-specific inhibitor (1L6-hydroxymethyl-chiroinositol-2-(R)-2-O-methyl-3-O-octadecyl-sn-glycerocarbon) and JNK-specific inhibitor (SP600125) significantly attenuated L-PGDS-induced cell migration as determined by the Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 6B) and wound healing assay (Fig. 6C). PGD2, however, did not significantly induce either AKT or JNK phosphorylation, suggesting that the L-PGDS protein and PGD2 may use distinct signaling pathways to promote cell migration. L-PGDS-induced cell migration was not affected by either SB203580 (p38-specific inhibitor) or PD98059 (MEK-specific inhibitor), arguing against the role of p38 MAPK or ERK pathway in the L-PGDS action (data not shown). C3 transferase, AKT-specific inhibitor, SP600125, SB203580, and PD98059 did not affect cell viability at the concentrations used in the current study (supplemental Fig. S5A). Moreover, specific inhibition of RhoA using C3 transferase reduced phospho-JNK, but not phospho-AKT levels, suggesting that RhoA is in the upstream of JNK (supplemental Fig. S5B). Taken together, the results indicate the importance of AKT, RhoA, and JNK pathways in L-PGDS-induced cell migration.

FIGURE 4.

L-PGDS regulates actin stress fibers and focal adhesion. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells (A) or mixed glial cells (B) were placed onto coverslips and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) or PGD2 (100 ng/ml). Cells were then fixed and stained with vinculin antibody for the detection of focal adhesion (green) or rhodamine-labeled phalloidin for the detection of stress fibers (red) (A). Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody was used for vinculin detection. Images were taken by confocal microscopy (magnification ×400). Scale bar, 25 μm. Cells were also examined by DAPI staining (blue). Relative fluorescence intensity of the stress fibers (red) and vinculin (green) in the different subcellular regions (inset) were quantified with the LSM 5 Exciter 4.2 software (Carl Zeiss). *, p < 0.05; compared with the untreated control (None).

FIGURE 5.

RhoA is involved in the L-PGDS-induced cell migration. After NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) or PGD2 (100 ng/ml) for 24 h, active RhoA was assessed by the effector pulldown assay followed by Western blot with a RhoA-specific antibody. The level of RhoA activity in each sample is proportional to the amount of RhoA precipitated in the pulldown assay (A). NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were either transiently transfected with L-pgds or treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) or PGD2 (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were treated with C3 transferase (RhoA-specific inhibitor, 0.2 μg/ml) for 30 min, and then either the Boyden chamber assay (B) or wound healing assay (C) was done to evaluate cell migration. The quantification of the cell migration was done by either measuring the degree of wound closure (the wound healing assay) or enumerating the migrated cells (the Boyden chamber assay). The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; compared with the treatments without inhibitors.

FIGURE 6.

Role of AKT and JNK in the L-PGDS-induced cell migration. After NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) or PGD2 (100 ng/ml) for 24 h, cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against AKT, phosphorylated AKT (Ser-473) (p-Akt), JNK, or phosphorylated JNK (p-Jnk) (A). Alternatively, NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were either transiently transfected with L-pgds cDNA or treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells were treated with 1L6-hydroxymethyl-chiroinositol-2-(R)-2-O-methyl-3-O-octadecyl-sn-glycerocarbon (AKT-specific inhibitor, 5 μm) and SP600125 (JNK-specific inhibitor, 5 μm) for 30 min, and then either the Boyden chamber assay (B) or wound healing assay (C) was done to evaluate cell migration. The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; compared with the treatments without inhibitors.

L-PGDS Promoted the Cell Migration in a PGD2-independent Manner

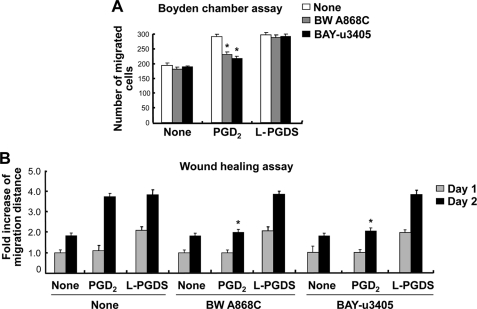

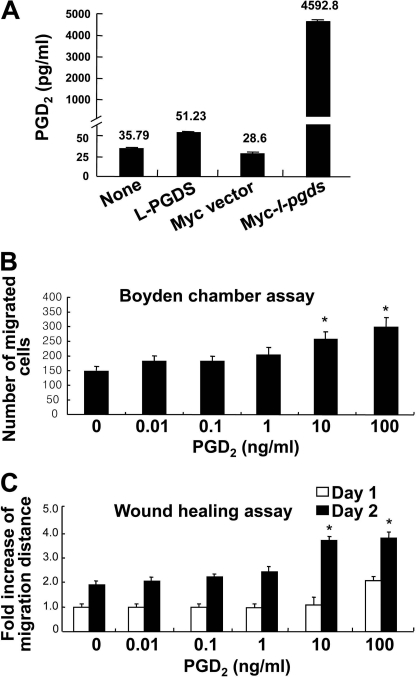

PGDS catalyzes the isomerization of PGH2, a common precursor of various prostanoids, to produce PGD2 (1, 3). Dissection of the signaling pathways showed that L-PGDS and PGD2 used partly different pathways to promote cell migration. This led to the hypothesis that L-PGDS may act independently of PGD2 production. PGD2 binds to two membrane receptors, D prostanoid receptor 1 (DP1) and DP2 (62, 63). The DP receptor antagonists, BW A868C (DP1-specific antagonist) and BAY-u3405 (DP2-specific antagonist) were used to examine the role of the PGD2 receptor in the actions of the L-PGDS. BW A868C and BAY-u3405 did not significantly attenuate the L-PGDS-induced NIH3T3 cell migration as determined by the Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 7A) and wound healing assay (Fig. 7B and supplemental Fig. S6C). On the contrary, both receptor antagonists inhibited the PGD2 effects on cell migration. BW A868C and BAY-u3405 did not affect cell viability at the concentrations used in the current study (supplemental Fig. S6, A and B). When the myc-tagged L-pgds was introduced into NIH3T3 cells, the amount of PGD2 in the culture media was increased ∼160.5 times compared with the control cells (Fig. 8A). Treatment with recombinant L-PGDS protein, however, exerted little effect on the PGD2 levels, as determined by a PGD2-MOX kit (Fig. 8A). No significant increase in cell migration occurred after exposure to PGD2 at concentrations lower than 10 ng/ml (Fig. 8, B and C, and supplemental Fig. S7). Thus, ∼50 pg/ml of PGD2 present in the culture media following L-PGDS treatment may not influence cell migration. These results indicate that L-PGDS may act through a PGD2-independent pathway. The PGD2-independent effect of L-PGDS on cell migration was similarly observed in glial cells (supplemental Fig. S8). DP receptor antagonists significantly attenuated the PGD2-induced glial migration, but not L-PGDS effects on glial cells. To further determine the role of PGD2 in the L-PGDS effects, we employed the L-PGDS protein with a point mutation at the active site of the enzyme. The mutant L-PGDS protein (C65A) without the ability to catalyze the conversion of PGH2 to PGD2 (40), also promoted cell migration of glia as well as NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 9), supporting that L-PGDS enhanced cell migration in a manner independent of PGD2 production.

FIGURE 7.

L-PGDS promotes cell migration through a PGD2-independent pathway. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were treated with the PGD2 (100 ng/ml) or recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of BW A868C (DP1-specific receptor antagonist, 10 nm) and BAY-u3405 (DP2-specific receptor antagonist, 10 nm) as indicated. Either the Boyden chamber assay (A) or the wound healing assay (B) was done to evaluate cell migration. The quantification of cell migration was done by either measuring the degree of wound closure (the wound healing assay) or enumerating the migrated cells (the Boyden chamber assay) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; compared with the treatments without antagonists under the same condition.

FIGURE 8.

Effects of L-PGDS treatment on the production of PGD2. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were either transfected with L-pgds cDNA or treated with L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Concentrations of PGD2 in medium were measured by PGD2 electroimmunoassay (A). The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were treated with different concentrations of PGD2, and then either the Boyden chamber assay (B) or the wound healing assay (C) was done to evaluate cell migration. The quantification of cell migration was done as described above. The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; compared with the untreated control at the same time point.

FIGURE 9.

Effects of the mutant L-PGDS protein on cell migration. A point mutation at the enzymatic active site (Cys65) was created by exchanging Cys65 with an alanine residue in L-PGDS. Primary microglia cultures (A), primary astrocytes (B), or NIH3T3 fibroblast cells (C) were treated with the mutant L-PGDS protein (10–100 ng/ml; L-PGDS (C65A)) or L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml), and then either the Boyden chamber assay (A and B) or wound healing assay (C) was done to evaluate cell migration. The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 compared with the untreated control (None) at the same time point.

L-PGDS Was an Inducer of Astrocyte Migration in Vivo

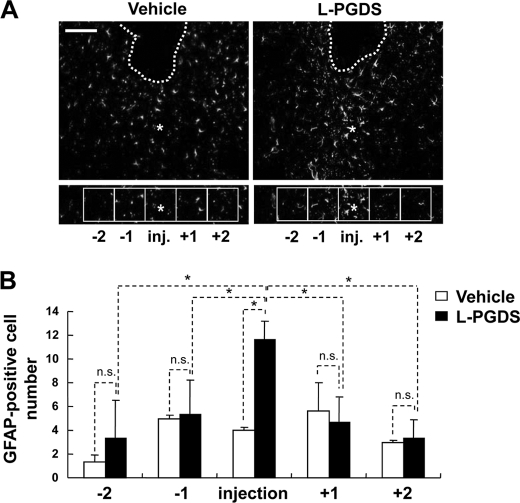

To confirm whether L-PGDS can act as an inducer of astrocyte migration in vivo, coronal brain sections were immunohistochemically stained with GFAP antibody at 48 h after intrastriatal injection of the vehicle or L-PGDS (Fig. 10A). The vehicle or L-PGDS protein was stereotaxically injected into the striatum of the mouse brain. The total number of GFAP-positive astrocytes in the periregion of the L-PGDS-injected site was almost 3-fold higher compared with the vehicle injection. For more details, the accumulated astrocytes were counted as previously described with a slight modification (64). Counting the GFAP-positive cell numbers in the five medial and lateral squares indicated that reactive astrocytes were mainly distributed within the injection site of L-PGDS but not the vehicle injection site (Fig. 10B). In a separate experiment, astrocyte migration-promoting activity of L-PGDS was confirmed by GFAP immunohistochemistry and quantification of horizontal brain sections following intracortical injection of L-PGDS (supplemental Fig. S9). These data demonstrate that L-PGDS enhances the migration and accumulation of astrocytes in brain.

FIGURE 10.

L-PGDS induces astrocyte migration in vivo. At 48 h after intrastriatal injection of the vehicle or L-PGDS protein (1 μl; 1 mg/ml), brain sections were stained with anti-GFAP antibody. Asterisks indicate the injection sites (inj.). Guide cannula was stereotaxically located in the intrastriatal region (dotted line). Boxes indicate the 500 × 500-μm squares placed for cell counting. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that the GFAP-positive cells were recruited into the injection site following L-PGDS protein injection. A representative microscopic image for each condition is shown (A). Values are the mean ± S.D. from three different animals and six independent sections per animal (B). *, p < 0.05; between the treatments indicated. n.s. = not significantly different. Scale bars, 500 μm.

L-PGDS Interacted with MARCKS to Promote Cell Migration

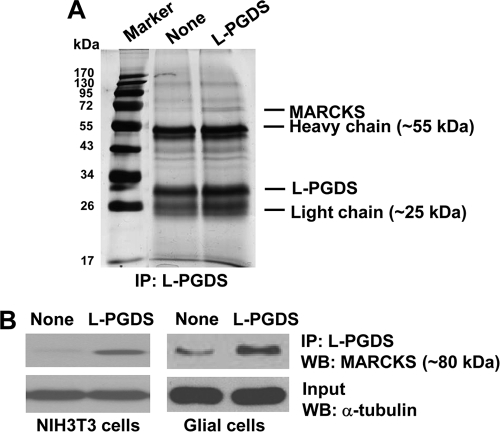

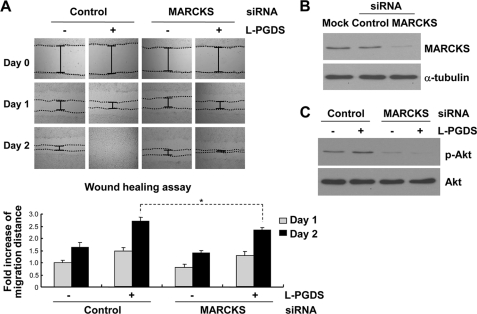

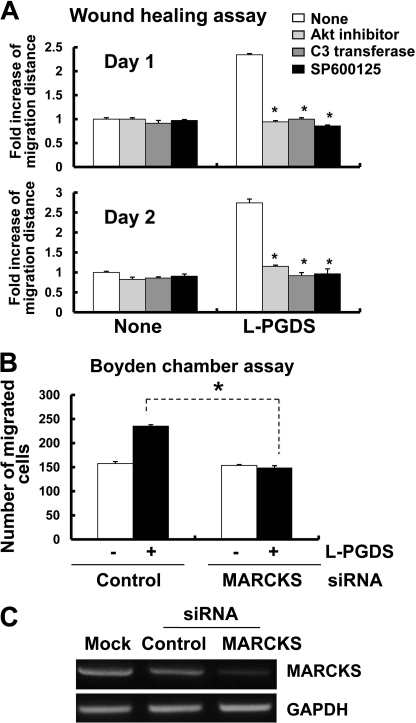

In an attempt to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms of L-PGDS-induced cell migration, L-PGDS-interacting proteins were identified by coimmunoprecipitation followed by LC-MS/MS analysis. Because we were mainly interested in the proteins on or near the cell surface, intact NIH3T3 cells were treated with L-PGDS protein, washed, and subjected to formaldehyde-mediated cross-linking. Afterward, L-PGDS-treated NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated using the anti-L-PGDS antibody. The proteins coimmunoprecipitated with L-PGDS were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining, which were then identified using LC-MS/MS analysis. The major protein coimmunoprecipitated was MARCKS (Fig. 11A). MARCKS is an actin cytoskeleton-binding protein that is localized to the plasma membrane. Next, the interaction between MARCKS and L-PGDS was independently confirmed by immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis in a separate experiment (Fig. 11B). NIH3T3 fibroblast cells or glial cells were treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with the L-PGDS antibody, followed by Western blot detection of MARCKS. This experiment verified that MARCKS and L-PGDS interact with each other in vitro. To determine the role of L-PGDS-MARCKS interaction in cell migration, the migration-promoting activity of L-PGDS was tested in NIH3T3 fibroblast cells, where Marcks expression was knocked down using siRNA. The wound healing assay revealed that Marcks siRNA transfection diminished the migration-inducing activity of the L-PGDS protein (Fig. 12A). The siRNA-mediated knockdown of Marcks expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 12B). The Marcks siRNA also inhibited the L-PGDS-induced phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 12C). Marcks knockdown, however, did not completely abolish either L-PGDS-induced cell migration or downstream signaling, indicating the existence of Marcks-independent pathways. Expression of the Marcks mRNA was detected in primary microglia and astrocyte cultures (supplemental Fig. S10). In mixed glial cells, inhibitors of AKT, RhoA, and JNK attenuated L-PGDS-induced cell migration, indicating that the AKT-RhoA-JNK axis similarly governs L-PGDS-induced glial migration (Fig. 13A). The role of Marcks in the L-PGDS-induced glial cell migration was again demonstrated using siRNA-mediated knockdown (Fig. 13, B and C). Taken together, these results suggest that L-PGDS may interact with MARCKS to induce cell migration through AKT and JNK pathways.

FIGURE 11.

Molecular interaction between L-PGDS and MARCKS. NIH3T3 cells were treated with buffer as a control or L-PGDS protein (1 μg/ml) for 24 h, and cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde. Proteins cross-linked with L-PGDS were immunoprecipitated followed by SDS-PAGE separation and silver staining (A). Coimmunoprecipitated proteins with anti-L-PGDS antibody were identified by LC-MS/MS. In a separate experiment, NIH3T3 fibroblast cells or mixed glial cells treated with L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) were immunoprecipitated with anti-L-PGDS antibody. Immunoprecipitates were run on a SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed for the expression of MARCKS by Western blot analysis (B). α-Tubulin in input was also detected as a control. Immunoprecipitation with recombinant protein G-agarose alone without L-PGDS antibody was also used as a control, where no specific band was detected (data not shown). The results are representative of more than three independent experiments. WB, Western blot.

FIGURE 12.

L-PGDS promotes cell migration through MARCKS. NIH3T3 fibroblast cells were transfected with control siRNA or Marcks siRNA. After 48 h, transfected cells were incubated with L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml), and the wound healing assay was done to evaluate cell migration (A). A representative microscopic image for each condition was shown (magnification ×100) (upper). The quantification of the cell migration was done by measuring the degree of wound closure (lower). The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; between the treatments indicated. The efficiency of Marcks knockdown by siRNA was confirmed by Western blot analysis (B). α-Tubulin was detected to confirm equal loading of the samples. Similarly, after siRNA transfection, L-PGDS protein-treated cells were lysed, and p-AKT and AKT protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis (C). The results are representative of more than three independent experiments.

FIGURE 13.

L-PGDS promotes glial cell migration through MARCKS and AKT-RhoA-JNK. Mixed glial cells were treated with recombinant L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml) in the presence of 1L6-hydroxymethyl-chiroinositol-2-(R)-2-O-methyl-3-O-octadecyl-sn-glycerocarbon (AKT-specific inhibitor, 5 μm), C3 transferase (RhoA-specific inhibitor, 0.2 μg/ml), or SP600125 (JNK-specific inhibitor, 5 μm), and then wound healing assay was done to evaluate cell migration (A). The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; compared with the treatments without inhibitors. Alternatively, mixed glial cells were transfected with control siRNA or Marcks siRNA. After 48 h, transfected cells were incubated with L-PGDS protein (100 ng/ml), and the Boyden chamber assay was done to evaluate cell migration after 24 h (B). The results are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05. The efficiency of Marcks knockdown by siRNA was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis (C). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

DISCUSSION

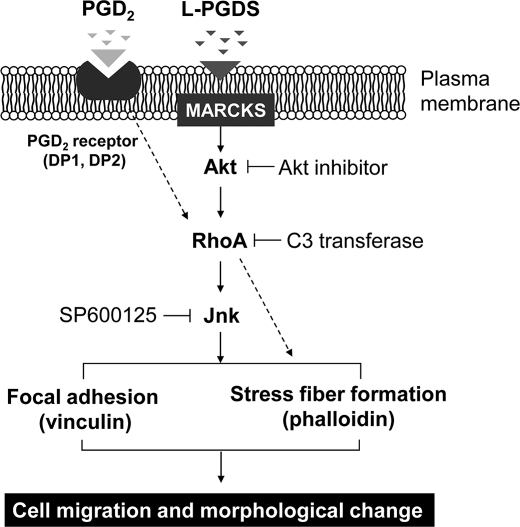

Here, we report that L-PGDS may induce the phenotypic changes of glia in reactive gliosis through MARCKS/AKT/Rho/JNK, but not PGD2 (Fig. 14). This is supported by several lines of evidence: 1) L-PGDS stimulated glial cell migration and morphological changes in vitro; 2) these effects were mediated by AKT, RhoA, and JNK pathways and the focal adhesion molecules, such as vinculin; 3) these effects were not attenuated by PGD2 receptor antagonists, and the enzymatically inactive mutant L-PGDS protein induced glial migration; 4) L-PGDS-induced glial migration was confirmed in rodent brain; and 5) L-PGDS interacted with MARCKS to induce cell migration, and knockdown of MARCKS expression suppressed AKT/JNK and cell migration.

FIGURE 14.

Possible mechanisms underlying L-PGDS-induced cell migration and morphological changes. L-PGDS promotes glial cell migration and morphological change via MARCKS in plasma membrane. L-PGDS·MARCKS complex may activate AKT, which in turn activates the RhoA. Activated RhoA may induce JNK activation and actin polymerization. Subsequently, JNK may induce focal adhesion formation through phosphorylation of focal adhesion molecules such as vinculin. In the mean time, PGD2 may exert similar effects through DP1 or DP2 and Rho pathways. L-PGDS, however, acts independently of PGD2 or PGD2 receptors.

Although L-PGDS is one of the most abundant proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid, little is known about its role in the CNS. Our results show that L-PGDS induces glial motility and morphological changes, which are associated with reactive gliosis. We further demonstrate that L-pgds mRNA is expressed in glial cells and neurons in culture, consistent with previous reports (2, 3, 65–68). Thus, L-PGDS produced in the CNS may participate in reactive gliosis by promoting glial cell migration and morphological changes in an autocrine or paracrine manner. Previously, L-PGDS was involved in peripheral inflammation. The expression and secretion of L-PGDS increased under inflammatory conditions in macrophages (20). In the CNS, glial cells often participate in inflammatory responses, and activated glial cells have been identified in a broad spectrum of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer disease (69), Parkinson disease (70), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (71), multiple sclerosis (72), and inherited photoreceptor dystrophies (73). L-PGDS secreted under these inflammatory conditions in the CNS may mediate the phenotypic changes associated with glial activation.

L-PGDS is not only a PGD2-producing enzyme, but also a member of lipocalin family. Our results indicate that the cell migration-promoting activity of L-PGDS does not depend on PGD2 production. Several experiments based on PGD2 receptor antagonists, PGD2 measurement, and the enzymatically inactive mutant form of the L-PGDS protein (C65A) suggest that L-PGDS may act on glia as a lipocalin-like ligand, rather than a PGD2-producing enzyme. When cells were transfected with L-pgds cDNA, they may produce both L-PGDS protein and PGD2. However, exogenously added L-PGDS protein can only exert its effects through the cell surface events and ensuing intracellular signaling pathways. These results suggest that extracellularly secreted L-PGDS proteins present in the cerebrospinal fluid modulate glial phenotypes like motility and shape as a secreted lipocalin, which is independent of PGD2 production.

This study demonstrated the molecular interaction between L-PGDS and MARCKS in NIH3T3 fibroblast cells and glial cells. The physical interaction of these two proteins appeared to induce cell migration via the AKT/JNK pathway. MARCKS is a key PKC substrate thought to regulate cellular adhesion and spreading, migration, proliferation, and fusion through its interaction with the cytoskeleton (74–76). MARCKS is localized to the plasma membrane and is an actin filament cross-linking protein. MARCKS phosphorylation and translocation are associated with alterations in the actin cytoskeleton (77) and may lead to changes in cell motility (78). Recently, MARCKS-induced cell migration was associated with the regulation of phospholipids and actin cytoskeleton in vascular endothelium (79). These previous reports are in agreement with the cell migration-inducing effects of MARCKS observed in the current study. Thus, L-PGDS may either directly or indirectly interact with MARCKS in glia to induce structural and functional changes in actin cytoskeleton, thereby promoting glial motility.

In summary, we present evidence that L-PGDS promotes the migration of microglia and astrocytes. Our results suggest that the L-PGDS-induced cell migration may be associated with augmented formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesion, which may be mediated through MARCKS/AKT/Rho/JNK pathways. Furthermore, the cell migration-inducing effect of L-PGDS on glial cells appears to be independent of PGD2. Our findings in vitro were supported by animal studies, where L-PGDS induced astrocyte recruitment into the injury site in the mouse brain. These results clearly establish an essential role of L-PGDS as a cell migration inducer in the CNS. Furthermore, as cell migration plays a central role in embryonic development, wound repair, inflammatory response, and tumor metastasis (80–82), the effects of L-PGDS on cell migration and morphology identified in this study may broaden our understanding of these biological processes.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) of Korean government Grant 2009-0078941 from the National Research Foundation and the Basic Science Research Program Grant 2010-0029460 from the National Research Foundation funded by the MEST.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S10.

- L-PGDS

- lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase

- PGD2

- prostaglandin D2

- MARCKS

- myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- DP1

- D prostanoid receptor 1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Urade Y., Fujimoto N., Hayaishi O. (1985) Purification and characterization of rat brain prostaglandin D synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 12410–12415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Urade Y., Hayaishi O. (2000) Prostaglandin D synthase. Structure and function. Vitam. Horm. 58, 89–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Urade Y., Hayaishi O. (2000) Biochemical, structural, genetic, physiological, and pathophysiological features of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1482, 259–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagata A., Suzuki Y., Igarashi M., Eguchi N., Toh H., Urade Y., Hayaishi O. (1991) Human brain prostaglandin D synthase has been evolutionarily differentiated from lipophilic-ligand carrier proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 4020–4024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kanaoka Y., Ago H., Inagaki E., Nanayama T., Miyano M., Kikuno R., Fujii Y., Eguchi N., Toh H., Urade Y., Hayaishi O. (1997) Cloning and crystal structure of hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase. Cell 90, 1085–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Urade Y., Fujimoto N., Kaneko T., Konishi A., Mizuno N., Hayaishi O. (1987) Postnatal changes in the localization of prostaglandin D synthetase from neurons to oligodendrocytes in the rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 15132–15136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka T., Urade Y., Kimura H., Eguchi N., Nishikawa A., Hayaishi O. (1997) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (β-trace) is a newly recognized type of retinoid transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15789–15795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beuckmann C. T., Aoyagi M., Okazaki I., Hiroike T., Toh H., Hayaishi O., Urade Y. (1999) Binding of biliverdin, bilirubin, and thyroid hormones to lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase. Biochemistry 38, 8006–8013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohri I., Taniike M., Okazaki I., Kagitani-Shimono K., Aritake K., Kanekiyo T., Yagi T., Takikita S., Kim H. S., Urade Y., Suzuki K. (2006) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase is up-regulated in oligodendrocytes in lysosomal storage diseases and binds gangliosides. J. Neurochem. 97, 641–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kanekiyo T., Ban T., Aritake K., Huang Z. L., Qu W. M., Okazaki I., Mohri I., Murayama S., Ozono K., Taniike M., Goto Y., Urade Y. (2007) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase/β-trace is a major amyloid β-chaperone in human cerebrospinal fluid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6412–6417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hansson S. F., Andréasson U., Wall M., Skoog I., Andreasen N., Wallin A., Zetterberg H., Blennow K. (2009) Reduced levels of amyloid-β-binding proteins in cerebrospinal fluid from Alzheimer disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 16, 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoffmann A., Conradt H. S., Gross G., Nimtz M., Lottspeich F., Wurster U. (1993) Purification and chemical characterization of β-trace protein from human cerebrospinal fluid. Its identification as prostaglandin D synthase. J. Neurochem. 61, 451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watanabe K., Urade Y., Mäder M., Murphy C., Hayaishi O. (1994) Identification of β-trace as prostaglandin D synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 203, 1110–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ragolia L., Palaia T., Frese L., Fishbane S., Maesaka J. K. (2001) Prostaglandin D2 synthase induces apoptosis in PC12 neuronal cells. Neuroreport 12, 2623–2628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maesaka J. K., Palaia T., Frese L., Fishbane S., Ragolia L. (2001) Prostaglandin D(2) synthase induces apoptosis in pig kidney LLC-PK1 cells. Kidney Int. 60, 1692–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ragolia L., Palaia T., Paric E., Maesaka J. K. (2003) Elevated L-PGDS activity contributes to PMA-induced apoptosis concomitant with down-regulation of PI3K. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, C119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xin X., Huber A., Meyer P., Flammer J., Neutzner A., Miller N. R., Killer H. E. (2009) L-PGDS (betatrace protein) inhibits astrocyte proliferation and mitochondrial ATP production in vitro. J. Mol. Neurosci. 39, 366–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ragolia L., Palaia T., Hall C. E., Maesaka J. K., Eguchi N., Urade Y. (2005) Accelerated glucose intolerance, nephropathy, and atherosclerosis in prostaglandin D2 synthase knock-out mice. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29946–29955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schuligoi R., Grill M., Heinemann A., Peskar B. A., Amann R. (2005) Sequential induction of prostaglandin E and D synthases in inflammation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 684–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joo M., Kwon M., Cho Y. J., Hu N., Pedchenko T. V., Sadikot R. T., Blackwell T. S., Christman J. W. (2009) Lipopolysaccharide-dependent interaction between PU.1 and c-Jun determines production of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase and prostaglandin D2 in macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 296, L771–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanaka R., Miwa Y., Mou K., Tomikawa M., Eguchi N., Urade Y., Takahashi-Yanaga F., Morimoto S., Wake N., Sasaguri T. (2009) Knockout of the L-pgds gene aggravates obesity and atherosclerosis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tokudome S., Sano M., Shinmura K., Matsuhashi T., Morizane S., Moriyama H., Tamaki K., Hayashida K., Nakanishi H., Yoshikawa N., Shimizu N., Endo J., Katayama T., Murata M., Yuasa S., Kaneda R., Tomita K., Eguchi N., Urade Y., Asano K., Utsunomiya Y., Suzuki T., Taguchi R., Tanaka H., Fukuda K. (2009) Glucocorticoid protects rodent hearts from ischemia/reperfusion injury by activating lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase-derived PGD2 biosynthesis. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1477–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirawa N., Uehara Y., Yamakado M., Toya Y., Gomi T., Ikeda T., Eguchi Y., Takagi M., Oda H., Seiki K., Urade Y., Umemura S. (2002) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase in essential hypertension. Hypertension 39, 449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miwa Y., Takiuchi S., Kamide K., Yoshii M., Horio T., Tanaka C., Banno M., Miyata T., Sasaguri T., Kawano Y. (2004) Identification of gene polymorphism in lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase and its association with carotid atherosclerosis in Japanese hypertensive patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 322, 428–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grill M., Peskar B. A., Schuligoi R., Amann R. (2006) Systemic inflammation induces COX-2 mediated prostaglandin D2 biosynthesis in mice spinal cord. Neuropharmacology 50, 165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kagitani-Shimono K., Mohri I., Oda H., Ozono K., Suzuki K., Urade Y., Taniike M. (2006) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (β-trace) is up-regulated in the αB-crystallin-positive oligodendrocytes and astrocytes in the chronic multiple sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 32, 64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garden G. A., Möller T. (2006) Microglia biology in health and disease. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 1, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Montesano R., Pepper M. S., Möhle-Steinlein U., Risau W., Wagner E. F., Orci L. (1990) Increased proteolytic activity is responsible for the aberrant morphogenetic behavior of endothelial cells expressing the middle T oncogene. Cell 62, 435–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee S., Park J. Y., Lee W. H., Kim H., Park H. C., Mori K., Suk K. (2009) Lipocalin-2 is an autocrine mediator of reactive astrocytosis. J. Neurosci. 29, 234–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCarthy K. D., de Vellis J. (1980) Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J. Cell Biol. 85, 890–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saura J., Tusell J. M., Serratosa J. (2003) High-yield isolation of murine microglia by mild trypsinization. Glia 44, 183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Enokido Y., Akaneya Y., Niinobe M., Mikoshiba K., Hatanaka H. (1992) Basic fibroblast growth factor rescues CNS neurons from cell death caused by high oxygen atmosphere in culture. Brain Res. 599, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Araki W., Yuasa K., Takeda S., Shirotani K., Takahashi K., Tabira T. (2000) Overexpression of presenilin-2 enhances apoptotic death of cultured cortical neurons. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 920, 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neptune E. R., Bourne H. R. (1997) Receptors induce chemotaxis by releasing the betagamma subunit of Gi, not by activating Gq or Gs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 14489–14494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bassi R., Giussani P., Anelli V., Colleoni T., Pedrazzi M., Patrone M., Viani P., Sparatore B., Melloni E., Riboni L. (2008) HMGB1 as an autocrine stimulus in human T98G glioblastoma cells. Role in cell growth and migration. J. Neurooncol. 87, 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee H., Kim Y. O., Kim H., Kim S. Y., Noh H. S., Kang S. S., Cho G. J., Choi W. S., Suk K. (2003) Flavonoid wogonin from medicinal herb is neuroprotective by inhibiting inflammatory activation of microglia. FASEB J. 17, 1943–1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kalla R., Bohatschek M., Kloss C. U., Krol J., Von Maltzan X., Raivich G. (2003) Loss of microglial ramification in microglia-astrocyte cocultures. Involvement of adenylate cyclase, calcium, phosphatase, and Gi-protein systems. Glia 41, 50–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee S., Lee J., Kim S., Park J. Y., Lee W. H., Mori K., Kim S. H., Kim I. K., Suk K. (2007) A dual role of lipocalin 2 in the apoptosis and deramification of activated microglia. J. Immunol. 179, 3231–3241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seo M., Lee W. H., Suk K. (2010) Identification of novel cell migration-promoting genes by a functional genetic screen. Faseb J 24, 464–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ragolia L., Hall C. E., Palaia T. (2007) Post-translational modification regulates prostaglandin D2 synthase apoptotic activity. Characterization by site-directed mutagenesis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 83, 25–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim S., Ock J., Kim A. K., Lee H. W., Cho J. Y., Kim D. R., Park J. Y., Suk K. (2007) Neurotoxicity of microglial cathepsin D revealed by secretome analysis. J. Neurochem. 103, 2640–2650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Akiyama H., Barger S., Barnum S., Bradt B., Bauer J., Cole G. M., Cooper N. R., Eikelenboom P., Emmerling M., Fiebich B. L., Finch C. E., Frautschy S., Griffin W. S., Hampel H., Hull M., Landreth G., Lue L., Mrak R., Mackenzie I. R., McGeer P. L., O'Banion M. K., Pachter J., Pasinetti G., Plata-Salaman C., Rogers J., Rydel R., Shen Y., Streit W., Strohmeyer R., Tooyoma I., Van Muiswinkel F. L., Veerhuis R., Walker D., Webster S., Wegrzyniak B., Wenk G., Wyss-Coray T. (2000) Inflammation and Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 21, 383–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garden G. A. (2002) Microglia in human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurodegeneration. Glia 40, 240–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McMillian M. K., Thai L., Hong J. S., O'Callaghan J. P., Pennypacker K. R. (1994) Brain injury in a dish. A model for reactive gliosis. Trends Neurosci. 17, 138–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Norton W. T., Aquino D. A., Hozumi I., Chiu F. C., Brosnan C. F. (1992) Quantitative aspects of reactive gliosis. A review. Neurochem. Res. 17, 877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Petrova T. V., Akama K. T., Van Eldik L. J. (1999) Cyclopentenone prostaglandins suppress activation of microglia. Down-regulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase by 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4668–4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Simpson K. J., Selfors L. M., Bui J., Reynolds A., Leake D., Khvorova A., Brugge J. S. (2008) Identification of genes that regulate epithelial cell migration using an siRNA screening approach. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1027–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Winograd-Katz S. E., Itzkovitz S., Kam Z., Geiger B. (2009) Multiparametric analysis of focal adhesion formation by RNAi-mediated gene knockdown. J. Cell Biol. 186, 423–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Suidan H. S., Nobes C. D., Hall A., Monard D. (1997) Astrocyte spreading in response to thrombin and lysophosphatidic acid is dependent on the Rho GTPase. Glia 21, 244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ramakers G. J., Moolenaar W. H. (1998) Regulation of astrocyte morphology by RhoA and lysophosphatidic acid. Exp. Cell Res. 245, 252–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. John G. R., Chen L., Rivieccio M. A., Melendez-Vasquez C. V., Hartley A., Brosnan C. F. (2004) Interleukin-1β induces a reactive astroglial phenotype via deactivation of the Rho GTPase-Rock axis. J. Neurosci. 24, 2837–2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hall A. (2005) Rho GTPases and the control of cell behavior. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 891–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Höltje M., Hoffmann A., Hofmann F., Mucke C., Grosse G., Van Rooijen N., Kettenmann H., Just I., Ahnert-Hilger G. (2005) Role of Rho GTPase in astrocyte morphology and migratory response during in vitro wound healing. J. Neurochem. 95, 1237–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen C. J., Ou Y. C., Lin S. Y., Liao S. L., Huang Y. S., Chiang A. N. (2006) l-Glutamate activates RhoA GTPase leading to suppression of astrocyte stellation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 1977–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pertz O., Hodgson L., Klemke R. L., Hahn K. M. (2006) Spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity in migrating cells. Nature 440, 1069–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kurokawa K., Matsuda M. (2005) Localized RhoA activation as a requirement for the induction of membrane ruffling. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4294–4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goulimari P., Kitzing T. M., Knieling H., Brandt D. T., Offermanns S., Grosse R. (2005) Gα12/13 is essential for directed cell migration and localized Rho-Dia1 function. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42242–42251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Scita G., Tenca P., Frittoli E., Tocchetti A., Innocenti M., Giardina G., Di Fiore P. P. (2000) Signaling from Ras to Rac and beyond. Not just a matter of GEFs. EMBO J. 19, 2393–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Qian Y., Corum L., Meng Q., Blenis J., Zheng J. Z., Shi X., Flynn D. C., Jiang B. H. (2004) PI3K-induced actin filament remodeling through Akt and p70S6K1. Implication of essential role in cell migration. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Huang C., Jacobson K., Schaller M. D. (2004) MAP kinases and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 117, 4619–4628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kito H., Chen E. L., Wang X., Ikeda M., Azuma N., Nakajima N., Gahtan V., Sumpio B. E. (2000) Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases in pulmonary endothelial cells exposed to cyclic strain. J. Appl. Physiol. 89, 2391–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Boie Y., Sawyer N., Slipetz D. M., Metters K. M., Abramovitz M. (1995) Molecular cloning and characterization of the human prostanoid DP receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18910–18916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Monneret G., Gravel S., Diamond M., Rokach J., Powell W. S. (2001) Prostaglandin D2 is a potent chemoattractant for human eosinophils that acts via a novel DP receptor. Blood 98, 1942–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Masana Y., Yoshimine T., Fujita T., Maruno M., Kumura E., Hayakawa T. (1995) Reaction of microglial cells and macrophages after cortical incision in rats. Effect of a synthesized free radical scavenger, (+/−)-N,N′-propylenedinicotinamide (AVS) Neurosci. Res. 23, 217–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Urade Y., Kitahama K., Ohishi H., Kaneko T., Mizuno N., Hayaishi O. (1993) Dominant expression of mRNA for prostaglandin D synthase in leptomeninges, choroid plexus, and oligodendrocytes of the adult rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9070–9074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Blödorn B., Brück W., Tumani H., Michel U., Rieckmann P., Althans N., Mäder M. (1999) Expression of the β-trace protein in human pachymeninx as revealed by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. J. Neurosci. Res. 57, 730–734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beuckmann C. T., Lazarus M., Gerashchenko D., Mizoguchi A., Nomura S., Mohri I., Uesugi A., Kaneko T., Mizuno N., Hayaishi O., Urade Y. (2000) Cellular localization of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (β-trace) in the central nervous system of the adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 428, 62–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taniike M., Mohri I., Eguchi N., Beuckmann C. T., Suzuki K., Urade Y. (2002) Perineuronal oligodendrocytes protect against neuronal apoptosis through the production of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase in a genetic demyelinating model. J. Neurosci. 22, 4885–4896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. El Khoury J., Luster A. D. (2008) Mechanisms of microglia accumulation in Alzheimer disease. Therapeutic implications. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 29, 626–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Orr C. F., Rowe D. B., Halliday G. M. (2002) An inflammatory review of Parkinson disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 68, 325–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sargsyan S. A., Monk P. N., Shaw P. J. (2005) Microglia as potential contributors to motor neuron injury in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Glia 51, 241–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Raivich G., Banati R. (2004) Brain microglia and blood-derived macrophages. Molecular profiles and functional roles in multiple sclerosis and animal models of autoimmune demyelinating disease. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 46, 261–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schuetz E., Thanos S. (2004) Microglia-targeted pharmacotherapy in retinal neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Drug Targets 5, 619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhao Y., Neltner B. S., Davis H. W. (2000) Role of MARCKS in regulating endothelial cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C1611–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Disatnik M. H., Boutet S. C., Lee C. H., Mochly-Rosen D., Rando T. A. (2002) Sequential activation of individual PKC isozymes in integrin-mediated muscle cell spreading. A role for MARCKS in an integrin signaling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2151–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Dulong S., Goudenege S., Vuillier-Devillers K., Manenti S., Poussard S., Cottin P. (2004) Myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) is involved in myoblast fusion through its regulation by protein kinase Cα and calpain proteolytic cleavage. Biochem. J. 382, 1015–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Calabrese B., Halpain S. (2005) Essential role for the PKC target MARCKS in maintaining dendritic spine morphology. Neuron 48, 77–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sheetz M. P., Sable J. E., Döbereiner H. G. (2006) Continuous membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion requires continuous accommodation to lipid and cytoskeleton dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35, 417–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kalwa H., Michel T. (2011) The MARCKS protein plays a critical role in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate metabolism and directed cell movement in vascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2320–2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Vicente-Manzanares M., Webb D. J., Horwitz A. R. (2005) Cell migration at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 118, 4917–4919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ridley A. J., Schwartz M. A., Burridge K., Firtel R. A., Ginsberg M. H., Borisy G., Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R. (2003) Cell migration. Integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]